Abstract

Introduction:

It has been hypothesized that postoperative epidural scar, postlaminectomy membrane, may be responsible for late neurological deterioration after cervical laminectomy in some cases, but there is a lack of radiological studies in the literature showing the clinical significance of postlaminectomy membrane. We describe a rare case with radiological evidence of dynamic spinal cord compression caused by the postlaminectomy membrane, which may have been related to neurological deterioration.

Case presentation:

A 73-year-old male developed recurrent cervical myelopathy 6 months after C4–C6 laminectomy. In addition to atlantoaxial subluxation and kyphotic deformity, dynamic spinal cord compression by the postlaminectomy membrane was identified on computed tomographic myelography. The patient underwent atlantoaxial fixation and C3–C7 posterior decompression and fixation combined with removal of the thick and firm postlaminectomy membrane adhering to the dura mater. Histopathological findings of the postlaminectomy membrane revealed chronic inflammation around exogenous materials, presumably surgical materials remaining after the first operation, in the thick fibrous tissue. The patient’s symptoms improved without recurrence of symptoms and postlaminectomy membrane formation for 3 years.

Discussion:

Compared with cervical laminoplasty, cervical laminectomy entails several postoperative problems, including postlaminectomy membrane formation. Postlaminectomy membranes may cause dynamic effects related to late neurological deterioration, and the evaluation of dynamic factors is important for neurological recurrence after cervical laminectomy. In the present case, chronic inflammation caused by surgical materials remaining after the first operation might have contributed to the rapid development of the postlaminectomy membrane.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical laminectomy is sometimes followed by undesirable sequelae, such as instability, kyphotic deformity and formation of an epidural scar termed ‘postlaminectomy membrane.’1–3 It has been hypothesized that postlaminectomy membrane may be responsible for late neurological deterioration in some cases, but few reports have radiologically demonstrated postlaminectomy membrane corresponding to actual neurological symptoms.1,4,5 Here we describe a rare case of recurrent cervical myelopathy with dynamic spinal cord compression by the postlaminectomy membrane, which may have been related to neurological deterioration. We have highlighted the importance of evaluating dynamic factors for neurological deterioration after cervical laminectomy. Pathological findings of the postlaminectomy membrane are also discussed.

Case presentation

A previously healthy 73-year-old man developed progressive bilateral clumsiness, hand paresthesia and gait disturbance caused by cervical spondylotic myelopathy (Figures 1a and b), and he underwent C4–C6 laminectomy and C7 partial laminectomy at another institution. The symptoms initially improved but recurred and deteriorated, and the patient was admitted to our institution at 6 months after surgery. The patient was unable to walk without the aid of a walker or ascend or descend stairs.

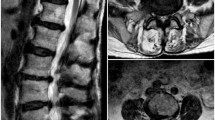

Radiological findings of the cervical spine before (a, b) and 6 months after (c, d) the first operation. Sagittal radiographs in the flexed and extended positions before (a) and after (c) surgery showed postoperative atlantoaxial subluxation and kyphotic deformity. The two lines in the flexed position indicate the distance between the anterior arch of atlas and the dens. Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance images before (b) and after (d) surgery showed a postoperative retro-odontoid mass with spinal cord compression and epidural scar formation (d, white arrows) without apparent spinal cord compression.

Radiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine revealed postoperative atlantoaxial subluxation with a retro-odontoid mass compressing the spinal cord and kyphotic deformity (Figures 1c and d). Regarding the previously decompressed levels, static MRI of the cervical spine in the neutral position showed the development of postoperative spinal cord thinning and a thick epidural scar, with no apparent spinal cord compression. However, dynamic computed tomographic myelography (CTM) of the cervical spine indicated intense spinal cord compression from the dorsal side at the previously decompressed levels in the extended position, despite an improvement of the cervical spine curvature in this position (Figure 2).

The patient underwent atlantoaxial transarticular fixation (Magerl technique) and C3–C7 posterior decompression with lateral mass screw fixation, combined with removal of the thick and firm epidural scar adhering to the dura mater (Figures 3a and 4a). Histopathological analysis of the epidural scar showed the thick fibrous tissue consisted of collagen fibers and capillary vessels. At several sites in the whole specimen, lymphocytes and macrophages had infiltrated around acellular, amorphous and basophilic deposits (Figures 3b and c). These findings suggested chronic inflammation caused by exogenous materials, presumably the remaining surgical materials from the first operation. Postoperative cervical CTM confirmed the disappearance of dynamic spinal cord compression (Figures 4b and c). Subsequently, the patient learned to walk without support as well as go up and down stairs and returned home 3 months after the second operation. He has had no clinical deterioration for 3 years, with only mild clumsiness and hand paresthesia remaining and with no recurrence of epidural scar formation (Figure 4d).

Intraoperative and histological findings of the postlaminectomy membrane. (a) Intraoperative image showing a thick epidural scar adhering to the dura mater. (b, c) Representative photomicrographs of hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained surgical specimens of the epidural scar tissue showing the infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages around acellular, amorphous and basophilic deposits. Original magnifications: ×40 (b) and ×400 (c).

Radiological findings of the cervical spine after the second operation. (a) Sagittal radiograph of the cervical spine obtained 4 weeks after the second operation. (b, c) Sagittal CTM of the cervical spine during flexion (b) and extension (c) obtained 3 weeks after the second operation showing resolution of the dynamic spinal cord compression. (d) Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the cervical spine obtained 2 years after the second operation.

Discussion

This case highlighted two interesting issues. First, postlaminectomy membrane after cervical laminectomy can cause dynamic effects related to neurological deterioration. Second, the rapid development of the postlaminectomy membrane in the present case might have been related to chronic inflammation caused by surgical materials.

Cervical laminectomy permits adequate decompression of the cervical spinal cord but has potential adverse outcomes, including instability, kyphosis and postlaminectomy membrane formation. Because of concerns related to these complications, cervical laminoplasty was developed in Japan in the 1970s as an alternative to cervical laminectomy. Recently, laminectomy with fusion or laminoplasty has often been chosen for posterior cervical decompression, with the expectation of preventing complications related to laminectomy without fusion.1,2 In the present case, the surgical procedure at the first operation was not optimal for the patient, and the postoperative course after the first operation may have been better if the patient underwent laminectomy with fusion or laminoplasty.

The significance of postlaminectomy membrane for neurological sequelae remains controversial, because several studies reported that compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots by postlaminectomy membrane was not observed on postoperative static MRI or intraoperative findings at reoperation.1 In contrast, Morimoto et al.4,5 described two cases of recurrent cervical myelopathy following cervical laminectomy, in which dynamic MRI disclosed dynamic spinal cord compression by postlaminectomy membrane. The dynamic effects of postlaminectomy membrane might have been overlooked in the previous studies based on static MRI and intraoperative findings.

In the present case, it was first considered that the neurological deterioration after the first operation was caused only by atlantoaxial subluxation and kyphotic deformity that had resulted from posterior supporting tissue damage caused by the surgery. However, an additional etiology was implied by postoperative spinal cord thinning and a thick epidural scar observed on MRI. Dynamic CTM disclosed dynamic spinal cord compression by the postlaminectomy membrane in the extended position, which had presumably caused the postoperative spinal cord thinning. It was unclear how much relevance the postlaminectomy membrane alone had to the recurrent myelopathy, because the atlantoaxial subluxation and kyphosis also developed postoperatively. However, surgical treatment without awareness of the postlaminectomy membrane may have resulted in an unsatisfactory outcome, because the correction of kyphosis without removing the postlaminectomy membrane might exacerbate spinal cord compression by the postlaminectomy membrane as observed in the extended position of CTM. This case illustrates the importance of the dynamic evaluation for late neurological deterioration after cervical laminectomy. Postlaminectomy membrane might latently affect symptoms when dynamic imaging is not performed. Therefore, the careful evaluation of dynamic factors might identify a relationship between the postlaminectomy membrane and neurological symptoms. We used CTM to evaluate dynamic factors because it has two advantages over dynamic MRI. First, although it involves dural puncture and radiation exposure, CTM has a lower risk for neurological deterioration because it requires a shorter scanning time with a flexed or extended position of the cervical spine. Second, CTM provides clear contrasted images with thinner slices and higher image resolution in axial and sagittal reconstructed slices, which effectively demonstrate dynamic changes in spinal cord compression.6,7

Histopathological analysis of the epidural scar revealed chronic inflammation caused by acellular, amorphous and basophilic deposits. These materials appeared exogenous and were presumably remaining surgical materials from the first operation. No surgical implants had been placed at the first operation; therefore, hemostatic agents applied intraoperatively might have caused the chronic inflammation. Unfortunately, the suspected material was unspecified because the first operation was performed at another institution. Although foreign body giant cells and foreign body granulomas were not observed, chronic inflammation was observed around the basophilic materials at several sites in the whole fibrous tissue, suggesting that chronic inflammation caused by remaining surgical materials was related to the etiology of the postlaminectomy membrane in this patient. In the literature, the etiology of postlaminectomy membranes was thought to be a postoperative healing process or epidural hematomas.1,8,9 Recently, Kuraishi et al.10 reported one case with a symptomatic postlaminectomy membrane caused by a foreign body reaction against hydroxyapatite spacers used in cervical laminoplasty. In that case, rapid development of epidural thick fibrous tissue resulted in compressive cervical myelopathy 2 months after the operation.10 The epidural scar in the present case also developed rapidly at 6 months after the first operation. The chronic inflammation caused by surgical materials might be related to the rapid formation of the postlaminectomy membrane, but the precise relationship remains unclear and further accumulation of cases is necessary.

In conclusion, this report presents a rare case with radiological evidence of dynamic spinal cord compression by the postlaminectomy membrane, which may have been associated with neurological deterioration. Dynamic evaluation is important for late neurological deterioration after cervical laminectomy. Chronic inflammation around surgical materials from the first operation was observed and might have contributed to the rapid development of the postlaminectomy membrane.

Additional Information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Ratliff JK, Cooper PR . Cervical laminoplasty: a critical review. J Neurosurg 2003; 98 (3 Suppl): 230–238.

Steinmetz MP, Resnick DK . Cervical laminoplasty. Spine J 2006; 6 (6 Suppl): 274s–281s.

Lee SE, Chung CK, Jahng TA, Kim HJ . Long-term outcome of laminectomy for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. J Neurosurg Spine 2013; 18: 465–471.

Morimoto T, Ohtsuka H, Sakaki T, Kawaguchi M . Postlaminectomy cervical spinal cord compression demonstrated by dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Case report. J Neurosurg 1998; 88: 155–157.

Morimoto T, Okuno S, Nakase H, Kawaguchi S, Sakaki T . Cervical myelopathy due to dynamic compression by the laminectomy membrane: dynamic MR imaging study. J Spinal Disord 1999; 12: 172–173.

Machino M, Yukawa Y, Ito K, Nakashima H, Kato F . Dynamic changes in dural sac and spinal cord cross-sectional area in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy: cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011; 36: 399–403.

Yoshii T, Yamada T, Hirai T, Taniyama T, Kato T, Enomoto M et al. Dynamic changes in spinal cord compression by cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament evaluated by kinematic computed tomography myelography. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014; 39: 113–119.

LaRocca H, Macnab I . The laminectomy membrane. Studies in its evolution, characteristics, effects and prophylaxis in dogs. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1974; 56b: 545–550.

Ronnberg K, Lind B, Zoega B, Gadeholt-Gothlin G, Halldin K, Gellerstedt M et al. Peridural scar and its relation to clinical outcome: a randomised study on surgically treated lumbar disc herniation patients. Eur Spine J 2008; 17: 1714–1720.

Kuraishi K, Hanakita J, Takahashi T, Minami M, Mori M, Watanabe M . Remarkable epidural scar formation compressing the cervical cord after osteoplastic laminoplasty with hydroxyapatite spacer. J Neurosurg Spine 2011; 15: 497–501.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Y Nakazato (Professor Emeritus, Gunma University) for valuable comments on the pathological findings of this study. Informed consent was obtained from the patient included in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kitahara, T., Hanakita, J. & Takahashi, T. Postlaminectomy membrane with dynamic spinal cord compression disclosed with computed tomographic myelography: a case report and literature review. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 3, 17056 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2017.56

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2017.56