Abstract

Introduction:

Many people with chronic spinal cord injury (SCI) develop shoulder pain, which can adversely impact transfers and independence. Yet effective treatments remain elusive.

Case Presentation:

This report presents two patients with tetraplegia who had long-standing shoulder pain. Our exam showed muscle weakness and point tenderness, suggestive of nerve entrapments of the radial and axillary nerves in the posterior shoulder. These nerves were surgically decompressed and post-operatively the patients’ pain resolved.

Discussion:

Shoulder nerve entrapments are uncommon but SCI patients may be at more risk due to their unique upper extremity demands. SCI providers should consider proximal nerve entrapments as a possible cause of shoulder pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After spinal cord injury (SCI), the upper limbs often take on new tasks such as wheelchair propulsion and transfers. Thus, maintaining arm and shoulder function becomes critical to post-injury independence. Overtime, these new demands on the upper limb take a toll and the majority of people with SCI develop shoulder pain.1 Subbarao surveyed 451 Veterans with SCI and found that 68% had shoulder pain.2 Shoulder pain is a large and important clinical problem for the SCI population.

Presently, the focus for SCI shoulder pain has been on musculoskeletal etiologies such as rotator cuff tears and glenohumeral impingement. Yet, treatments for these musculoskeletal problems are often ineffective or require excessive limitations on transfers and mobility. In this report, we present two cases of shoulder pain in people with SCI caused by entrapment of radial and axillary nerve sat the level of the shoulder. These patients responded to surgical release, which provided long-term pain relief and required minimal post-operative rehabilitation. Nerve entrapments at the shoulder are rare in the able-bodied population but can be a treatable cause of shoulder pain in the SCI individual.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old right-hand-dominant man with a C6 AIS A spinal cord injury (his right arm was stronger with a C7 level of injury) presented with right shoulder pain (Supplementary Video 1). He had this pain for 25 years and complained of throbbing shoulder pain worse at night. He also noted shoulder pain when exercising and during wheelchair transfers. He denied any sensory changes in his hand. Previous treatment included a distal clavicle resection, which did not improve his pain.

Physical exam

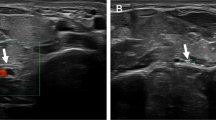

His physical exam was significant for marked weakness in his right posterior deltoid and triceps: both were a 4 on manual muscle testing. On exam, he had pain with palpation and a positive scratch collapse test at the quadrangular space.3

Studies

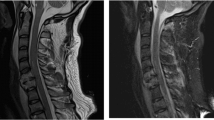

MRI showed glenohumeral impingement. Pre-operative EMG showed slight denervation of the triceps, no visible changes in the deltoid muscles.

Intervention

Patient underwent release of the axillary nerve in the quadrangular space and the radial nerve in the proximal triceps arcade. The axillary and radial nerves were both released through the same incision along the posterior border of the deltoid. The nerves were identified and all constricting fascial and fibrotic bands were released around each nerve.

Post-operative course

There were no restrictions on activity (patient could transfer and wheel his chair right after surgery). The patient had resolution of his pain and was able to sleep through the night as of post-operative day number one. At suture-removal 2 weeks post-operative, equal bilateral strength was noted in the post deltoid and triceps. His pain has not returned 30 months since intervention.

Case 2

A 56-year-old right-hand-dominant paralympian male with a T4 SCI presented with 1.5 years of left shoulder pain. The pain had begun after a fall injuring his left shoulder. He had undergone physical therapy and rest. He complained of night pain that woke him from sleep. The pain limited his ability to perform independent wheelchair transfers and work with his left shoulder elevated. He was unable to transfer from wheelchair to floor without assistance.

Physical exam

Manual testing showed left sided weakness of posterior deltoid, triceps, wrist extension and thumb extension. The patient had pain upon pressure over quadrangular space, but no sensory disturbance in the left hand.

Studies

MRI showed slight cuff degeneration. EMG showed signs of carpal tunnel syndrome bilaterally, but no denervation of the axillary or radial innervated muscles.

Intervention

Patient underwent release of his axillary nerve at the quadrangular space and radial nerve at the proximal triceps arcade, through one incision at the posterior border of the deltoid.

Post-operative course

After surgery his only restriction was to hold off on vigorous exercise such as hand cycling for two weeks. The night pain dissipated within two days, and on the third post-operative day he was able to transfer without assistance from wheelchair to floor. Two weeks after surgery, equal bilateral strength was noted in the posterior deltoid, triceps and wrist/thumb extensors. At 18 months after surgery, the patient is still pain-free and has full function of his left shoulder/arm.

Discussion

People with spinal cord injury are living longer fuller lives and maintaining independence, and quality of life is increasingly important. Shoulder pain is a common frustrating problem for persons with SCIs and treatments are often inadequate. Few patients describe shoulder pain before injury (8%), but after becoming wheelchair users 67% reported a history of shoulder pain.4 The importance of shoulder pain should not be underestimated as it can result in loss of ability to operate a manual chair, perform transfers and potentially prevent the ability to live independently. These case reports highlight nerve entrapment as another anatomic abnormality causing shoulder pain. Though these patients had abnormal musculoskeletal findings on MRI in the shoulder region, the nerve entrapments (not able to be seen on imaging) were the primary pain generators. Proximal nerve entrapments at the shoulder are not common like carpal tunnel syndrome but awareness of their possibility and careful exam can reveal them.

Shoulder pain after SCI is likely a multifactorial process. The majority of the literature on shoulder pain has focused upon the glenohumeral joint. It is thought that wheeling and dependence on the upper extremity for functional tasks results in maladaptive positioning and stress around the glenohumeral joint. Most patients with shoulder pain undergo an X-ray and an MRI, and these studies often demonstrate abnormalities. One study showed that individuals with paraplegia had an incidence of rotator cuff tears of 63% compared to 15% in able-bodied volunteers.5 The clinical relevance of these imaging findings remains unclear as asymptomatic pathology is found as people age. For example, Milgrom found that 80% of people over 80 have rotator cuff tears.6 It remains unknown if people with SCI, with their increased upper extremity demands, may develop imaging changes seen with age earlier than able-bodied population, and thus some of these radiographic findings may be asymptomatic. When a provider is caring for a patient with shoulder pain who has abnormal imaging, it is easy for the differential diagnosis to focus on the musculoskeletal pathology.

The radial and axillary nerves are also potentially at risk of injury from the maladaptive glenohumeral positioning seen in the SCI individual. Both these nerves wrap around the proximal humerus through confined areas: the triangular and quadrilateral spaces. Compression of both the radial and axillary nerve at the level of the shoulder are uncommon in the able-bodied literature. Both conditions are found in active adults and overhead athletes such as volley ball players.7,8 The etiology of compression is thought to be a combination of scarring from previous trauma/ and/or hypertrophy of the muscles bordering the space.9 Therefore, it may be that SCI patients with their intense demands on their upper limbs develop hypertrophy and injuries similar to those of overhead throwing athletes.

For the patients in this report, nocturnal pain provided one clue that nerve entrapment should be suspected. Both patients complained of shoulder pain waking them up at night. Nocturnal pain is classically associated with nerve entrapments. For example, in carpal tunnel syndrome, waking up at night with pain is pathognomonic. Radial and axillary entrapments often are dull achy posterior shoulder pain. Nerve entrapments are diagnosed by thorough history and physical exam. Radiologic studies are generally not helpful. Interestingly electro-diagnostic studies may also be normal (patient no. 2). As we know from other distal entrapments, muscle changes seen on EMG are often a late findings and other electro-diagnostic techniques to establish entrapments such as 'inching' are not feasible at the level of the shoulder. Therefore, the clinician must rely on history and a physical exam (Table 1).10 In our exam, both arms are evaluated simultaneously looking for subtle differences in strength, point tenderness over the known areas of nerve compression and a positive scratch collapse test. This combination of physical exam findings plus the history make the diagnosis.11

Treatment of nerve entrapments includes a variety of options. Rest and physical therapy is the first line treatment. For the patients in this case report, upper limb rest was not an option, as it would have severely limited their independence. Surgical release of the nerves is the next step in treatment and is a soft tissue operation releasing compressive bands, similar to carpal and cubital tunnel release. Like the carpal tunnel patient who has night pain, surgical release quickly results in pain relief. Surgical release of proximal nerve entrapments in the SCI individual can be safe and successful with careful patient selection.

Conclusion

These case reports highlight nerve entrapments as a cause of shoulder pain in the SCI patient. Rotator cuff tears and glenohumeral arthritis are common in the SCI population but nerve entrapments in these high demand limbs should also be considered, especially as treatment with surgical release requires minimal post-operative rehabilitation and is associated with low morbidity. Clinicians should look for proximal nerve entrapments when caring for patients with shoulder pain.

Ethics

This is a case report, so it does not fall under the auspices of human research so there is no formal IRB. The video of the patient is identifiable and a release for video is included in the submission.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

Pentland WE, Twomey LT . Upper limb function in persons with long-term paraplegia and implications for independence: Part I. Paraplegia 1994; 32: 211–218.

Subbarao JV, Klopfstein J, Turpin R . Relevance and impact of wrist and shoulder pain in patients with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 1995; 18: 9–13.

Cheng CJ, Mackinnon-Patterson B, Beck JL, Mackinnon SE . Scratch collapse test for evaluation of carpal and cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am 2008; 33: 1518–1524.

Alm M, Saraste H, Norrbrink C . Shoulder pain in persons with thoracic spinal cord injury: prevalence and characteristics. J Rehabil Med. 2008; 40: 277–283.

Akbar M, Balean G, Brunner M, Seyler TM, Bruckner T, Munzinger J et al. Prevalence of rotator cuff tear in paraplegic patients compared with controls. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92: 23–30.

Milgrom C, Schaffler M, Gilbert S, van Holsbeeck M . Rotator-cuff changes in asymptomatic adults. The effect of age, hand dominance and gender. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995; 77: 296–298.

McAdams TR, Dillingham MF . Surgical decompression of the quadrilateral space in overhead athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2008; 36: 528–532.

Hoskins WT, Pollard HP, McDonald AJ . Quadrilateral space syndrome: a case study and review of the literature. Br J Sports Med 2005; 39: e9.

Ng AB, Borhan J, Ashton HR, Misra AN, Redfern DR . Radial nerve palsy in an elite bodybuilder. Br J Sports Med 2003; 37: 185–186.

Hagert CG, Hagert E . Manual Muscle testing-a clinical examination technique for diagnosing focal neuropathies in the upper extremity. In: Slutsky DJ (eds). Upper Extremity Nerve Repair-Tips and Techniques: a Master Skills Publication. The American Society for Surgery of the Hand: Rosemont, IL, USA, 2008, pp 451–466.

Hagert E, Hagert CG . Upper extremity nerve entrapments: the axillary and radial nerves--clinical diagnosis and surgical treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014; 134: 71–80.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplemental Information accompanies the paper on the Spinal Cord Series and Cases website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Curtin, C., Hagert, CG., Hultling, C. et al. Nerve entrapment as a cause of shoulder pain in the spinal cord injured patient. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 3, 17034 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2017.34

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2017.34

This article is cited by

-

Anterior interosseous nerve neuropathy in a patient with spinal cord injury: case report and literature review

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2022)