Abstract

Introduction:

Osteochondromas are common benign tumors of bone and spinal involvement is uncommon. Solitary spinal osteochondromas may produce a wide variety of symptoms depending on their location and relationship to adjacent neural structures.

Case Presentation:

Herein, we present a case of solitary osteochondroma arising from the posterior arch of C1, causing left-sided ascending numbness and paresthesia and difficulty walking. The lesion was totally resected through a posterior approach. Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of benign osteochondroma.

Discussion:

Spinal cord compression is uncommon in spinal osteochondromas because in most cases the tumor grows out of the spinal column. To prevent neurological compromise, complete surgical removal is mandatory when an intraspinal osteochondroma with cord compression is diagnosed, which also helps to prevent recurrence. Our literature review of similar cases indicates that despite the old belief that C2 is the most commonly involved vertebra for osteochondromas, C1 is actually the most commonly involved vertebra in the cervical region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteochondroma, or osteocartilaginous exostosis, is the most common skeletal neoplasm1 and constitutes 20–50% of all benign bone tumors and 10–15% of all bone tumors.2 It is commonly found in the appendicular skeleton but is very rarely seen in the spine.3 Osteochondromas may be solitary or multiple when associated with hereditary multiple exostoses or osteochondromatosis, an autosomal dominant trait.3,4 Only 1.3–4.1% of solitary osteochondromas originate in the spine.5 Rarely, spinal osteochondromas may present with nerve root or cord compression.4,6 Even symptoms due to vertebral artery occlusion have been described.7 When the tumor causes pain or neurological complications or when the diagnosis is unclear, it should be excised surgically.5 Herein, we present a case of osteochondroma arising from the posterior arch of C1 in a 48-year-old female with a favorable long-term surgical outcome and discuss the relevant literature.

Case presentation

Methods

Using PubMed and Google search engines, we performed a thorough review of English language medical literature for reported cases of solitary cervical osteochondromas with neurological symptoms. Patient’s characteristics, including age, sex, symptoms, the site of origin on the cervical vertebra, recurrences and the method of surgery were all reviewed.

Case Illustration

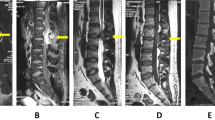

A 48-year-old woman presented with symptoms of left-sided paresthesia and weakness, ascending numbness and difficulty in walking over 6 months. Her gait became steadily cumbersome during the last 2 months. Physical examination revealed no apparent sensory or motor impairment. Deep tendon reflexes were exaggerated, particularly on the left side and the left plantar reflex had an extensor response. Hoffman's reflex was positive in the left hand. Other neurological examinations were normal. MRI of the cervical spine revealed a hypointense mass lesion on parasagittal section with cord compression. (Figure 1a). Also, the compression due to spinal cord displacement was clear on axial sections (Figure 1b). Computed Tomography (CT) of the cervical vertebrae revealed the bony nature of the tumor and its origin from posterior arch of the first cervical vertebra (Figure 1c). The patient underwent a posterior cervical approach and laminectomy (without fusion) and radical resection of the tumor. The postoperative course was uneventful and the symptoms improved immediately after surgery, and the patient fully recovered without any residual deficit. Histopathological analysis of the specimen confirmed the diagnosis of osteochondroma (Figure 2). At 6-month follow-up, the patient had no clinical problems. On serial control radiography and CT scans, the lesion was found to have been completely removed without any evidence of recurrence at 5 years' long-term follow-up (Figure 1d).

Sagittal T2-weighted MRI demonstrating severe cord compression by an extradural hypointense lesion originating from posterior arch of c1 (a). Axial T1-weighted at the corresponding level shows cord distortion by the hyposignal mass arising from posterior elements of C1 vertebra (b). Axial CT Scan depicting the relatively hyperdense lesion originating from c1 posterior arch with both intraspinal and extraspinal growth (c). Postoperative CT scan showing total resection of the tumor with sufficient cord decompression (d).

Discussion

According to the 2002 WHO definition, osteochondroma (osteocartilaginous exostosis) is a cartilage capped benign bony neoplasm on the outer surface of bone.8 Osteochondromas make up about 8.5% of all bone tumors and about 36% of benign lesions.5 These tumors are thought to arise in the peripheral portion of the growth plate. A focus of metaplastic cartilage forms and grows through progressive endochondral ossification as a consequence of trauma or a congenital perichondral deficiency.3 These tumors develop as either solitary or multiple lesions when associated with hereditary multiple exostosis, an autosomal dominant condition.9

Most osteochondromas originate from the diaphysis of long bones, predominantly involving the distal femur, proximal tibia, proximal humerus and pelvis.10 Spinal involvement is rare.11–13 Only 1.3–4.1% of solitary osteochondromas arise in the spine,14 where they constitute up to 0.4% of intraspinal tumors or 3.9% of solitary spinal tumors.5 Unlike pedunculated long bone osteochondromas, vertebral osteochondromas are sessile.10

In terms of gender distribution, solitary lesions affect males more than females, and the common age of onset is in the second or third decade of life.12,15,16 The demographic pattern reveals the onset of these lesions at the mean age of 20 in the hereditary variety and 30 in the solitary subtype;16 however, a case as old as 84 years has been reported.17

These lesions can be found at any part of the vertebral column, but the cervical spine is the most common (50%).4,18 The propensity for exostoses to develop in the cervical spine has been attributed to the mobility of the cervical spine.3,19,20 Greater stress due to mobility could cause microtrauma and displacement of a portion of the epiphyseal growth cartilage9,20 with consequent displacement of a portion of physeal cartilage and exostosis formation.19 C2 is the most common vertebrae to be involved in the cervical spine, followed by C3 and C6,18 but in the present case, the lesion is in C1 posterior arch, which is not the commonest site among cervical spine cases.

Cord compression is very unusual in patients with spinal osteochondromas11,18,21–23 because most of the lesions grow out of the spinal canal.10,20 When there is compression of neural structures, this can cause various neurological symptoms and signs depending on the level and degree of cord and/or root compression. In our case, the tumor was projected inwards from the posterior arch of C1, leading to apparent cord compression. Because of the complex imaging of the vertebral bones, spinal osteochondromas are sometimes difficult to be readily detected on plain radiographs.9 CT Scan is the imaging modality of choice. Not only it can demonstrate the cartilaginous and osseous components of the tumor, but also clearly defines the tumor’s extent and its relationship to the vertebral and neural elements of the spine.21 On MRI, osteochondromas are seen as isointense lesions with a low signal rim produced by the cortical bone. MRI provides excellent demonstration of the spinal cord and nerve root compression,9 so it is valuable for detecting evidence of neurological compression, which appears as low signal on T1-weighted sequences and high signal on T2-weighted sequences.1

Asymptomatic lesions can be followed conservatively,10,24 but surgery should be considered whenever the diagnosis is not definite, or the patient is in pain or in the case of progressive neurological deficit.24 Nearly all reported cases of spinal osteochondromas presenting with spinal cord compression are treated with laminectomy or hemilaminectomy, owing to the posterior origin of most osteochondromas.21 In this case, we planned for a radical excision of the tumor through C1 posterior arch removal to relieve the cord compression and to prevent recurrence. Incomplete resection may lead to recurrence, which occurs in 2–5% of lesions.15,18,23 Complete excision of the cartilaginous cap is essential to prevent recurrence.18,22 The mean time to recur has been reported to be 5 years.17

A thorough review of English literature using PubMed and Google found 80 reported cases of solitary cervical osteochondroma. The male-to-female ratio was 1.51:1. The youngest patient reported was 8 years old and the oldest one was 77 years old, and the mean age for solitary cervical osteochondroma in this review being 35.8 years.

The most common symptoms were arm radicular pain, limb weakness, neck mass and limb numbness. Other less common symptoms included dysphagia, headache, sleep apnea, hand atrophy, difficulty in walking, head tilt and dizziness. On examination, the most common signs were limb weakness, hyper reflexia, limb hyposthesia and neck mass. Other less common signs included restricted cervical range of motion, local tenderness, occipital neuralgia, limb atrophy, cranial nerve palsy, Horner’s syndrome and torticollis.

It is believed that C2 is the most common vertebrae to be involved by solitary osteochondroma (24.4%), followed by C1 (18.83%) and C7 (15.15%).4,9,11,15,18,20,23 Our review of literature, including the present case, showed that C1 is the most involved vertebra in the cervical region (24%), followed by C2 (21%) and C5 (18%). The C3 body was the most uncommon site (5.4%). Although the exact origin of the tumor remains unidentified in most reports, the laminae were found to be the most common site, and less commonly involved structures were the pedicles, facets, spinous processes, transverse processes and anterior arch of C1 vertebra. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of reported C1 osteochondromas.

Nearly all reported cases of cervical osteochondromas presenting with spinal cord compression have been treated with laminectomy or hemilaminectomy alone due to the posterior origin of most cervical osteochnodromas. In 17 cases of this review, patients were followed up for signs of recurrence for a range of 6 months to 10 years (mean: 3/4 years). Two recurrences occurred 6 years postoperatively and one in 28 months. At 5-year follow-up of the present case, no signs of radiological recurrence have been witnessed.

Conclusion

Solitary C1 osteochondroma is rarely reported in middle-aged women. Gradual cord compression is a reason for delays in diagnosis; however, in most cases, the tumor is successfully treated by laminectomy with favorable outcomes. Complete surgical removal is necessary to prevent recurrence. Despite the old belief, C1 should be considered as the most commonly involved vertebrae.

References

Faik A, Filali S, Lazrak N, Hassani S, Hassouni N . Spinal cord compression due to vertebral osteochondroma: report of two cases. Joint Bone Spine 2005; 72: 177–179.

Murphey M, Choi J, Mark J, Kransdorf M, Flemming D, Gannon F . Imaging of osteochondroma: variants and complications with radiologic pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics 2000; 20: 1407–1434.

Quirini G, Meyer J, Herman M, Russell E . Osteochondroma of the thoracic spine: an unusual cause of spinal cord compression. AJNR 1996; 17: 961–964.

Lotfinia I, Vahedi P, Tubbs S, Ghavame M, Meshkini A . Neurological manifestations, imaging characteristics, and surgical outcome of intraspinal osteochondroma Clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine 2010; 12: 474–489.

Ertekin A, Atilla E, Nurullah Y . Osteochondroma of the upper cervical spine: a case report. Spine 1996; 21: 516–518.

Kroppenstedt S, Blumenthal D, Niepage S, Behse F, Oestmann J, Unterberg A . Osteochondroma of the cervical spine—a surprising finding in a liver transplanted patient with polyneuropathy and polyradiculitis: case report. Surg Neurol 2002; 57: 411–414.

Castro J, Rodiño J, Touceda A, Castro D, Pinzón A . Cervical spine osteochondroma presenting with torticollis and hemiparesis. Neurocirugia (Astur) 2014; 25: 94–97.

Lotfinia I, Baradaran A, Ghavami M . Lumbar spine osteochondroma causing sciatalgia: an unexpected presentation in hereditary multiple exostoses. Iran J Radiol 2009; 6: 69–72.

Kyung M, Jung L, Yeon K, Hyung K, Sung J, In K et al. Osteochondroma of the cervical spine extending multiple segments with cord compression. Pediatr Neurosurg 2006; 42: 304–307.

Brastianos P, Pradilla G, McCarthy E, Gokaslan Z . Solitary thoracic osteochondroma case report and review of literature. Neurosurgery 2005; 56: E1379.

Gunay C, Atalar H, Yildiz Y, Saglik Y . Spinal osteochondroma: a report on six patients and a review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010; 130: 1459–1465.

Sakai D, Mochida J, Toh E, Nomura T . Spinal osteochondromas in middle-aged to elderly patients. Spine 2002: 27: E503–E506.

Zhao C, Jiang S, Jiang L, Dai L . Horner syndrome due to a solitary osteochondroma of C7 a case report and review of the literature. Spine 2007; 32: E471–E474.

Schomacher M, Suess O, Kombos T . Osteochondromas of the cervical spine in atypical location. Acta Neurochir 2009; 151: 629–633.

Bonic E, Kettner N . A rare presentation of cervical osteochondroma arising in a spinous process. Spine 2012; 37: E69–E72.

Sil K, Basu S, Bhattacharya M, Chatterjee S . Pediatric spinal osteochondromas: case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Neurosci 2006; 1: 70–71.

Lotfinia I, Sayyahmelli S . Rare symptomatic osteochondroma of the spine in a very old patient. Neurosurg Q 2011; 21: 22–25.

Srikantha U, Devibhagavatula I, Satyanarayana S, Somanna S . Chandramoulib. spinal osteochondroma: spectrum of a rare disease Report of 3 cases. J Neurosurg Spine 2008; 8: 561–566.

Bess R, Robbin M, Bohlman H, Thompson G . Spinal exostoses analysis of twelve cases and review of the literature. Spine 2005; 30: 774–780.

Ohtori S, Yamagata M, Hanaoka E, Suzuki H, Takahashi K, Sameda H et al. Osteochondroma in the lumbar spinal canal causing sciatic pain: report of two cases. J Orthop Sci 2003; 8: 112–115.

Lotfinia I, Sayyahmelli S . Solitary thoracic spine osteochondroma: an unusual cause of spinal cord compression. Neurosurg Q 2001; 21: 280–282.

Rahman A, Bhandari PB, Hoque SU, Ansari A, Hossain AM . Solitary osteochondroma of the atlas causing spinal cord compression: a case report and literature review. BMJ Case Rep 2012; 2012: bcr1220115435.

Volokhina Y, Dang D . Unique case of solitary osteochondroma of left lamina of C2 presenting with neurologic deficits. Radiol Case Rep 2011; 6: 551.

Gul rkanlar D, Acıduman A, Gul naydın A, Kocak H, Clelik N . Solitary intraspinal lumbar vertebral osteochondroma: a case report. J Clin Neurosci 2004; 11: 911–913.

Mitsumori K, Otsuka K, Iwasaki Y, Yada K . Osteochondroma of the high cervical spine. a case report. No Shinkei Geka 1975; 3: 867–871.

Julien J, Riemens V, Vital C, Lagueny A, Miet G . Cervical cord compression by solitary osteochondroma of the atlas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1978; 41: 479–481.

Wu K, Guise E . Osteochondroma of the atlas. a case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1978; 136: 160–162.

Lanzieri C, Solodnik P, Sacher M, Hermann G . Computed tomography of solitary spinal osteochondromas. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1985; 9: 1042–1044.

Slavotinek J, Brophy B, Sage M . Bony exostosis of the atlas with resultant cranial nerve palsy. Neuroradiology 1991; 33: 453–454.

Calhoun JM, Chadduck WM, Smith JL . Single cervical exostosis: report of a case and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 1992; 37: 26–29.

Lopez-Barea F, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, Hernandez-Moneo JL, Alvarez-Ruiz F, Perez-Alvarez M . Tumors of the atlas. 3 incidental cases of osteochondroma, benign osteoblastoma, and atypical Ewing’s sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994; 307: 182–188.

Morikawa M, Numaguchi Y, Soliman J . Osteochondroma of the cervical spine. MR findings. Clin Imaging 1995; 19: 275–278.

Khosla A, Martin D, Awwad E . The solitary intraspinal vertebral osteochondroma: an unusual cause of compressive myelopathy: features and literature review case report. Spine 1999; 24: 77–81.

Sharma M, Arora R, Deol P, Mahapatra A, Mehta V, Sarkar C . Osteochondroma of the spine: an enigmatic tumor of the spinal cord. A series of 10 cases. J Neurosurg Sci 2002; 46: 66–70.

Yoshida T, Matsuda H, Horiuchi C, Taguchi T, Nagao J, Aota Y et al. A case of osteochondroma of the atlas causing obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Acta Otolaryngol 2006; 126: 445–448.

Ozturk C, Tezer M, Hamzaoglu A . Solitary osteochondroma of the cervical spine causing spinal cord compression. Acta Orthop Belg 2007; 73: 133–136.

Yagi M, Ninomiya K, Kihara M, Horiuchi Y . Symptomatic osteochondroma of the spine in elderly patients. J Neurosurg Spine 2009; 11: 64–70.

Wang V, Chou D . Anterior C1-2 osteochondroma presenting with dysphagia and sleep apnea. J Clin Neurosci 2009; 16: 581–582.

Miyakoshi N, Hongo M, Kasukawa Y, Shimada Y . Cervical myelopathy caused by atlas osteochondroma and pseudoarthrosis between the osteochondroma and lamina of the axis: case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2010; 50: 346–349.

Er U, Şimşek S, Yiğitkanlı K, Adabağ A, Kars H . Myelopathy and quadriparesis due to spinal cord compression of C1 laminar osteochondroma. Asian Spine J 2012; 6: 66–70.

Zhang Y, Ilaslan H, Hussain S, Bain M, Bauer T . Solitary C1 spinal osteochondroma causing vertebral artery compression and acute cerebellar infarct. Skeletal Radiol 2014; 44: 299–302.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lotfinia, I., Vahedi, A., Aeinfar, K. et al. Cervical osteochondroma with neurological symptoms: literature review and a case report. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 3, 16038 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2016.38

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2016.38

This article is cited by

-

Cervical osteochondroma: surgical planning

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2020)