Abstract

Introduction:

Traumatic central cord syndrome (CCS) is the most frequently encountered incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI). The patient presents weakness, which is usually greater in the upper extremities than in the lower extremities, secondary to damage to the cervical spinal cord and anatomic distribution of the corticospinal tracts. CCS is seen commonly after a hyperextension mechanism in older patients with spondylotic changes. There are few literature reports regarding CCS in pediatric patients. We present an unusual case of traumatic CCS in a pediatric patient.

Case Presentation:

A 15-year-old male patient, victim of bullying at school, received cervical blunt trauma with a plastic tube. Within 3 h, the patient developed generalized weakness, which was greater in the upper extremities than in the lower extremities. Upon evaluation, the patient was found with marked upper extremity weakness compared to the lower extremities, with a Manual Muscle Test difference of 11 points. Imaging studies showed contusive changes in the C4-C7 central spinal cord. After rehabilitation therapies the patient gained 23 points in MMT at the day of discharge.

Discussion:

Different etiologies of CCS have previously been described in pediatric patients. However, this is the first case that describes a bullying event with cervical blunt trauma and subsequent CCS. In this case, history and physical examination, along with imaging studies, helped in the diagnosis, but it is important to be aware of the possibility of SCI without radiographic abnormalities, as it is common in the pediatric population. CCS occurs rarely in pediatric patients without underlying pathology. Physicians must be aware of the symptoms and clinical presentation in order to provide treatment and start early rehabilitation program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical spinal cord injuries are uncommon and heterogeneous in the pediatric population.1 Although rare, traumatic central cord syndrome (CCS) is one of the most common incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI) syndrome; its epidemiology has not been reported. It is for this reason that we present an unusual case of cervical SCI in a young child after receiving blunt trauma to the cervical area with a plastic (polyvinyl chloride) tube, as a victim of bullying at school. It is our intent to describe this entity and to review the literature of this disease related to blunt trauma/bullying.

Clinical case

A 15-year-old, right-handed male patient with past medical history of hypothyroidism, attention deficit hyperactive disorder and major depressive disorder, previously independent, suffered cervical trauma with a plastic tube while being a victim of bullying at school. Although left on the floor alone, the patient was able to stand and walk back to his classroom asymptomatic. After 3 h, the patient developed progressive bilateral numbness on the tip of fingers, with associated upper limb distal muscle weakness (wrists and fingers). Weakness progressed rapidly to the lower limb muscle, which interfered with ambulation. Owing to worsening of symptoms, the patient was taken to an emergency room for evaluation.

On physical examination, the patient was found to be alert, awake and following commands and with stable vital signs. There were no gross signs of external trauma except for pain in the cervical area. Motor strength evaluation showed significant upper extremity weakness with a difference of 11 points in the manual muscle test (MMT) when comparing upper versus lower extremity strength (see Table 1). Sensory examination revealed absent soft touch and pin-prick in right C6, C7, C8 and T1 dermatome distribution. Proprioception and vibration evaluation was intact.

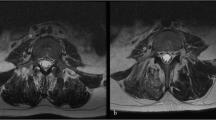

Initial imaging of plain radiographs showed no evidence of fracture, dislocation or cervical spine instability, and a head computed tomography without contrast with no acute intracranial pathology. However, a magnetic resonance imaging of cervicothoracic region without contrast was positive for spinal cord contusive changes involving C4–C7, but no evidence of cord hemorrhage. Vertebral body contusive changes involving C2–T1 was also seen (see Figure 1).

Patient was admitted to PICU for close neurological and cardiorespiratory serial evaluation. Initial management included intravenous hydration and pain medication. No surgical management was recommended by the neurosurgery service. Laboratory workup was essentially normal. After medical stabilization and no deterioration, the patient was transferred to the general pediatric ward. The patient started with daily physical and occupational rehab therapies. In addition, bilateral resting splints for the upper extremities and a right ankle-foot orthosis were prescribed. Throughout the 3 weeks the patient was hospitalized, and the patient showed improvement in functionality and strength, with a total of 23 points improvement in MMT (12 in upper extremities (UEx) and 11 in lower extremities (LEx)) on the day of discharge (see Table 1). During the hospital stay there were no bladder dysfunction reported by the patient.

Clinical features and diagnosis

Diagnosis of CCS is usually based on the clinical criteria characterized by disproportionately more motor impairment of the upper extremities compared with the lower extremities, with variable involvement of bladder dysfunction and sensory abnormality below the affected level.2 A difference of at least 10 points in the ASIA (American Spinal Injury Association) MMT should be found when comparing the upper extremities with the lower extremities.3,4

Magnetic resonance imaging is the examination of choice for the diagnosis of traumatic CCS, showing intramedullary hypersignal on T2-weighted and STIR (Short TI recovery) sequences consistent with edema, as well as lesions of ligaments and intervertebral discs.5,6 Magnetic resonance imaging is also useful for the assessment of hemorrhage and may show the presence of prevertebral hematoma or disruption of posterior ligaments, which may suggest spinal column instability.7–9

X-rays may be normal if there is no pre-existing pathology. The underlying congenital narrowing can be assessed with the Pavlov or Torg ratio.10 This is a ratio of canal size to anterior-to-posterior vertebral body dimension on the lateral X-ray that should be >0.82.10 Cervical dynamic X-rays have an important role in the radiographic assessment of the eventually associated discoligamentous instability.11 Significant radiographic pathologic views may or may not accompany the injury in plain radiographs. The absence of radiographic evidence is more frequent in children younger than 8 years and in those with high injury severity scores.12

A large multi-institutional series demonstrated that up to 50% of children with symptomatic SCI presented with no radiologic abnormality, suggesting that even the most accurate of imaging modalities will not be able to show what should be apparent on careful physical examination.13

As discussed previously, differences in the anatomical and biomechanical characteristics of the pediatric cervical spine predispose children to present with a SCI without radiographic abnormality and/or relationship to a hyperextension injury.14,15 SCI without radiographic abnormality is specific to children and extremely rare in adults, and occurs in ~15–25% of all pediatric cervical spine injuries.

Pathophysiology

CCS was first described in 1954, characterized by disproportionately more motor impairment of the upper extremities compared with the lower extremities, with variable involvement of bladder dysfunction and sensory abnormality below the affected level.2 CCS is classically known to affect older persons with cervical spondylosis and a hyperextension injury, where a spinal cord compression occurs between bony spurs anteriorly and buckling of the ligamentum flavum posteriorly.2,16

In general, three main mechanisms have been postulated: (1) young patients sustaining a high speed injury, such as in motor vehicle accidents, diving accident or a fall from height; (2) in older patients (>50 years) because of a hyperextension force in an already degenerate spine; (3) low-velocity trauma in a patient with an acute central disc herniation.2,17–21

As seen in adults, the most common cause of injury in children is motor vehicle accidents.22–24 Some recreational activities such as diving place children at greatest risk for cervical spine injury.1 Violence, including penetrating trauma, is the third leading cause of SCI in children.1 Child abuse as a cause of cervical spine injury is rare but may be underreported in the pediatric population.13 Limited data are available on bullying cases.

Children with a narrow canal, secondary to spinal stenosis or congenital malformation, may be predisposed to spinal cord concussion when the canal is further narrowed in cervical hyperflexion or in hyperextension.25,26 Upper cervical spine injuries (C1–4) are almost twice as common as lower cervical injuries (C5–7); a small subset of patients may present with both an upper and lower cervical spine injury. Several differences in the anatomical and biomechanical characteristics of the pediatric cervical spine predispose children to present with a SCI without radiographic abnormality and/or relationship to a hyperextension injury.14,15

Differences include the relative cephalocervical disproportion and the ossification status of the spine. The child’s head represents ~25% of total body mass combined. This in combination with a poorly developed cervical musculature gives a mechanical disadvantage to the pediatric cervical spine.15 In addition, in children the incompletely ossified synchondrosis through the base of C2 is a point of relative weakness and, therefore, a region prone to disruption from a distracting force.15 Other anatomic differences are the anteriorly wedged orientation of the vertebral bodies, the horizontal orientation of the facets and the absence of uncinate processes on the vertebral bodies.15 The net result of these anatomic variations is that children have less skeletal resistance to flexion and rotation forces, with a greater degree of the resistance being shifted to the ligaments.15 Also, the spinal cord may be compressed by a transient subluxation or distraction.14,15 This helps explain why children are less prone to spine fractures and more likely to present with SCI without radiographic abnormality.15

Discussion

SCI in the pediatric population, especially in children younger than 15 years old, is a rare event but may have serious consequences.27 SCI has been reported to occur in <1% of those of patients following blunt trauma.13,28

Traumatic CCS is the most common incomplete SCI regardless of its mechanism of lesion.29,30 Two large retrospective studies in the pediatric trauma databases revealed that the incidence of traumatic CCS ranges between 1.5 and 5%.13,31

Diagnosis of SCI in the pediatric population may be challenging. A potential failure of diagnosis is present because of its heterogeneous presentation in this population, especially after minor trauma.32

In our patient, his past medical history of hypothyroidism, attention deficit hyperactive disorder and major depressive disorder did not predispose him for CCS. Nevertheless, there are literatures that have shown that subjects with attention deficit hyperactive disorder and depression are at an increased risk of being bullied.33

Recovery

Prognosis of functional recovery is generally better in the pediatric population when compared with adults. The rate of recovery following SCI in the pediatric population is also thought to be faster. More than one-half of these patients experienced spontaneous recovery of motor weakness; however, as time went on, lack of manual dexterity, neuropathic pain, spasticity, bladder dysfunction and imbalance of gait rendered their activities of daily living nearly impossible.12 Overall prognosis for functional recovery is good.

Conclusion

Pediatric SCI remains a relatively rare condition relative to its prevalence in the adult population. Although CCS is the most common incomplete spinal cord syndrome, literature in the pediatric population is very limited. Prognosis of functional recovery is generally better in the pediatric population when compared with adults. Anatomical and biomechanical characteristics of pediatric cervical spines are obviously different relatively to adults. This makes diagnosis of SCI in the pediatric population more challenging.

Accuracy in the diagnosis of CCS is based on the history of trauma to the cervical area and a careful physical examination, where there is disproportionately more motor impairment of the upper extremities compared with the lower extremities of at least 10 points in the ASIA MMT. Imaging studies, mostly magnetic resonance imaging, can assist in the diagnosis showing different pathologies such as spinal cord edema, hemorrhage or cervical vertebral ligament disruption.31

References

Leonard JC . Cervical spine injury. Pediatr Clin N Am 2013; 60: 1123–1137.

Schneider RC, Cherry G, Pantek H . The syndrome of acute central cervical spinal cord injury; with special reference to the mechanisms involved in hyperextension injuries of cervical spine. J Neurosurg 1954; 11: 546–577.

Pouw MH, Van Middendorp JJ, Van Kampen A, Hirschfield S, Veth RPH, Curt A et al. Diagnostic criteria of traumatic central cord syndrome. Part 1: A systematic review of clinical descriptors and scores. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 652–656.

Van Middendorp JJ, Pouw MH, Hayes KC, Williams R, Chhabra HS, Putz C et al. Diagnostic criteria of traumatic central cord syndrome. Part 2: A questionnaire survey among spine specialists. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 657–663.

Miyanji F, Furlan JC, Aarabi B, Arnold PM, Fehlings MG . Acute cervicaltraumatic spinal cord injury: MR imaging findings correlated with neuro-logic outcome—prospective study with 100 consecutive patients. Radiology 2007; 243: 820–827.

Scholtes F, Adriaensens P, Storme L, Buss A, Kakulas BA, Gelan J et al. Correlation of postmortem 9.4 tesla magnetic resonance imagingand immunohistopathology of the human thoracic spinal cord 7 months after traumatic cervical spine injury. Neurosurgery 2006; 59: 671–678.

Collignon F, Martin D, Lenelle J, Stevenaert A . Acute traumatic central cordsyndrome: magnetic resonance imaging and clinical observations. J Neurosurg 2002; 96 (Suppl 1): 29–33.

Schaefer DM, Flanders A, Northrup BE, Doan HT, Osterholm JL . Magnetic resonance imaging of acute cervical spine trauma. Correlation with severity of neurologic injury. Spine 1989; 14: 1090–1095.

Song J, Mizuno J, Inoue T, Nakagawa H . Clinical evaluation of traumatic centralcord syndrome: emphasis on clinical significance of prevertebral hyperintensity, cord compression, and intramedullary high-signal intensity on magnetic resonance imaging. Surg Neurol 2006; 65: 117–123.

Pavlov H, Torg JS, Robie B, Jahre C . Cervical spinal stenosis: determination with vertebral body ratio method. Radiology 1987; 164: 771–775.

Molliqaj G, Payer M, Schaller K, Tessitore E . Acute traumatic central cord syndrome: a comprehensive review. Neurochirurgie 2014; 60: 5–11.

Aarabi B, Koltz M, Ibrahimi D . Hyperextension cervical spine injuries and traumatic central cord syndrome. Neurosurg Focus 2008; 25: E9.

Patel JC, Tepas DL III, Mollitt DL, Pieper P . Pediatric cervical spine injuries: defining the disease. J Pediatr Surg 2001; 36: 373–376.

Bosch PP, Vogt MT, Ward WT . Pediatric spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality (SCIWORA): the absence of occult instability and lack of indication for bracing. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002; 27: 2788–2800.

Proctor MR . Spinal cord injury. Crit Care Med 2002; 30: S489–S499.

Parke WW . Correlative anatomy of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988; 13: 831–837.

Harrop JS, Sharon A, Ratliff J . Central cord injury: pathophysiology management and outcomes. Spine J 2006; 6: 198S–206S.

Ishida Y, Tominaga T . Predictors of neurological recovery in acute cervical cord injury with only upper limb extremity impairment. Spine 2002; 27: 1652–1657.

Dai L, Jia L . Central cord injury complicating acute disc herniation in trauma. Spine 2000; 25: 331–336.

Hayes KC, Askes HK, Kakulas BA . Retropulsion of intervertebral disc associated with traumatic hyperextension of the cervical spine and absence of vertebral fracture: an uncommon mechanism of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 544–547.

Taylor AR, Blackwood W . Paraplegia in hyperextension cervical injuries with normal radiological appearances. J Bone Surg 1948; 30B: 245–248.

Kokoska ER, Keller MS, Rallo MC, Weber TR . Characteristics of pediatric cervical spine injuries. J Pediatr Surg 2001; 36: 100–105.

McKinley W, Santos K, Meade M, Brooke K . Incidence and outcomes of spinal cord injury clinical syndromes. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30: 215–224.

Dietrich AM, Ginn-Pease ME, Bartkowski HM, King DR . Pediatric cervical spine fractures: predominantly subtle presentation. J Pediatr Surg 1991; 26: 995–999.

Grabb PA, Pang D . Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality in children. Neurosurgery 1994; 35: 406–414.

Rathbone D, Johnson G, Letts M . Spinal cord concussion in pediatric athletes. J Pediatr Orthop 1992; 12: 616–620.

Parent S, Mac-Thion J . Spinal Cord Injury in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review of Literature. J Neurotrauma 2011; 28: 1515–1524.

Viccellio P, Simon H, Pressman BD, Shah MN, Mower WR, Hoffman JR et al. A prospective multicenter study of cervical spine injury in children. Pediatrics 2001; 108: E20.

Yamazaki T, Yanaka K, Fujita K, Kamezaki T, Uemura K, Nose T . Traumatic central cord syndrome: analysis of factors affecting the outcome. Surg Neurol 2005; 63: 99–100.

Li XF, Dai LY . Acute central cord syndrome: injury mechanisms and stress features. Spine 2010; 35: E955–E964.

Apple DF, Anson CA, Hunter JD, Bell RB . Spinal cord injury in youth. Clin Pediatr 1995; 34: 90–95.

Junk SK, Shin HJ, Kang HD, Oh SH . Central cord syndrome in a 7-year-old boy secondary to standing high jump. Pediatr Emerg Care 2014; 30: 640–642.

Roy A, Hartman CA, Veenstra R, Oldehinkel AJ . Peer dislike and victimisation in pathways from ADHD symptoms to depression. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015; 24: 887–895.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ramírez, N., Arias-Berríos, R., López-Acevedo, C. et al. Traumatic central cord syndrome after blunt cervical trauma: a pediatric case report. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 2, 16014 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2016.14

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2016.14

This article is cited by

-

A case of real spinal cord injury without radiologic abnormality in a pediatric patient with spinal cord concussion

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2017)