Abstract

Study design:

Case report.

Objectives:

We present for the first time an adult patient with cervical intramedullary immature teratoma with metastatic recurrence.

Setting:

Peking university Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, China.

Methods:

A 30-year-old woman presented with rapidly progressive quadriplegia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an intramedullary tumor occupying C1–C2 of the upper spinal cord. An urgent operation, consisting of decompression by laminectomy and tumor gross resection, was performed under a preoperative diagnosis of spinal glioma. The histological diagnosis was immature teratoma. The patient received local radiotherapy after gross total resection. The serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) levels were normal postoperatively, until these were evaluated on the 10th month with neurological deterioration. Metastatic recurrences were demonstrated on MRI with lesions located at the levels of C5–C6 and T11–12. Removal of the second tumors was performed and the pathological examination identified a malignant germ cell tumor (yolk sac tumor). The patient was then referred to chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Results:

No tumor regrowth was encountered and the patient remained stable for 6 months after adjuvant therapy.

Conclusion:

Immature teratoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of holocord tumors in the adult with rapidly progressing symptoms and if found should be radically excised if possible. Adjuvant therapy should be the salvage therapy for this recurrent tumor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intramedullary imature teratomas in adults are very rare, and only one case of purely immature teratoma in the adult has been identified.1 We report another case of an exclusively intramedullary immature teratoma located at the uppermost cervical level with rapid progressive deterioration and metastatic recurrence by cerebrospinal fluid dissemination.

Case report

A 30-year-old woman, presented to us with a 1-week history of neck pain. Three days prior to admission, she noticed progressive weakness in both upper and lower limbs and could not walk later. She was quadriplegic with the lower limb hyperreflexia, the presence of bilateral babinski and ankle clonus. All sensory modalities were impaired below the level of C4.

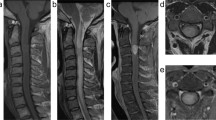

Computed tomography and subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an expansile, poorly demarcated, intramedullary tumor at the C1–C2 levels, which appeared hypointense on T1-weighted and mixed signal intensity on T2-weighted images on MRI (Figures 1a–d). The radiological diagnosis was spinal intramedullary glioma, such as an astrocytoma or an ependymoma.

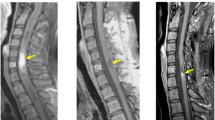

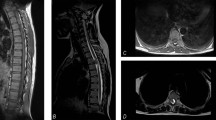

Preoperative plain computed tomography scan shows a hypodense lesion located at C1–C2 levels without calcification (a). Preoperative axial T1-weighted MRI shows the bad-delineated mass of hypointense signal located exclusively in the cervical spinal cord (b). Sagittal MRI (c and d) depicts the fusiform-shaped and eccentrically located intramedullary tumor at the C1–C2 levels, appearing hypointense on T1-weighted and mixed signal intensity on T2-weighted images with adjacent spinal cord edema. The cystic lesion within the spinal cord distal to the mass is quite visible (see white dovetail arrow). (e and h) Immediately postoperative Gd-enhanced T1-weighted sagittal and axial MRI shows gross-total removal of the tumor (black arrowhead). Sagittal (f and g) and axial (i and j) on the 10th month follow-up MRI images with contrast reveal two metastatic extramedullary lesions at C4–C6 and T11–12, respectively, appearing highly enhanced with heterogeneous features. No changes are observed in the previous operation site (see white double arrow). (k) Postoperative T1-weighted sagittal MRI with contrast depicts near-total resection of the cranial and caudal tumors, respectively. Of note, numerous additional disseminated enhancing foci nodules are seen along the leptomeninges and dura, likely representing metastatic drop lesions (long white arrows).

The patient was urgently undertaken operation without any enhancement of the imaging because of rapid neurological deterioration. A laminectomy from C1 to C3 was performed. The cervical spinal cord appeared normal but swollen on the surface. The tumor was grayish and soft in consistency. A relative cleavage plane between the soft mass and the nervous tissue was identified, although no real capsule was found. It was thought that a total resection of the tumor was achieved.

Histopathological examination revealed immature neuroepithelium in a primitive mesenchymal background. No malignant features or areas of yolk sac tumor were identified (Figures 2a and b).

Photomicrographs of the tumor (first operation) show immature neural tissue with the formation of neural tubes (a) and no immunoreactivity for AFP (b). Histopathological examination (second operation) reveals a typical yolk sac tumor with reticular network of medium-sized polygonal malignant cells, moderately pleomorphic hyperchromatic to vesicular nuclei, with many areas of myxoid degeneration. Intracellular hyaline bodies were present (c). Immunohistochemical images: tumor cells showing strong positivity for AFP (d). Scale bars=200 μm (a), 100 μm (b–d).

Immunohistological staining result were as follows: neuron-specific enolase (+), Ki-67 index (40%), and HCG and AFP (−). On the basis of all these findings, a histological diagnosis of immature teratoma with an immaturity of high grade was made.

Considering that the pathologic results were immature type, the patient received local radiotherapy (14 Gy). The follow-up MRI obtained 1 week and 6 months postoperatively demonstrated the absence of tumor recurrence (Figures 1e and h). Meanwhile, the serum AFP and HCG levels were normal in 1 week, 2 weeks, 2 and 6 months postoperatively but elevated on 10th month (Figure 3). The patient again showed myelopathic symptoms with subdural extramedullary tumor recurrence at the level of C5–C6 and T11–12 on MRI 10th month postoperatively (Figures 1f–j).

Second tumor resection was performed. The histopathology showed a diagnosis of yolk sac tumor (Figures 2c and d). The patient’s neurological symptoms improved and the serum AFP and HCG levels gradually fell but fail to return to normal. Postoperative MRI showed that the recurrent tumors were near-totally resected, but adjacent meningeal enhancements were noted (Figure 1k). The patient was discharged for radio- and chemotherapy 4 weeks after surgery. The former craniospinal fractionated radiotherapy consists of a total dose of 36 Gy to 20 fractiones; the latter comprised etoposide phosphate (150 mg, days 1–4) and cisplatin (35 mg, days 1–4) after the course of the radiotherapy. Because of the severe myelosuppression, no further treatment was given. The serum HCG levels fell to normal level, and the serum AFP level just gained near normal value during the chemotherapy. The residual tumor did not change on the 6-month follow-up MRI examination.

Discussion

The clinical presentation of teratomas is nonspecific from those of other intramedullary tumors. The period of our case is very short, which may be partly interpreted as its immature histological feature with high mitotic activity leading to rapid evolution.

Although MRI and computed tomography can supply informative details, in the present case, the signal feature is not typical lacking characteristics compatible with heterogeneous solid and cystic components and the presence of fatty tissue and calcification.

No consensus regarding the treatment of this tumor has been achieved because of the limited collective experience in their management. Surgery should be the first choice and total surgical resection of the tumor should be the aim, as the certification of immature or malignant teratoma cannot be made preoperatively; moreover, the presence of only mature elements in the resected portion does not exclude the presence of immature elements in remaining parts, which more commonly encountered recurrence.2

Currently, the role of adjuvant therapy for intraspinal immature teratoma remains unproven given the minimal information available in the literature concerning the response of congenital immature teratoma. Tapper and Lack3 reported a low benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy in five patients with intramedullary immature teratoma in the children group. For two patients with radical resected immature teratomas, chemotherapy was unsuccessful in preventing from recurrence. However, it is also recognized that, in older children, chemotherapy with platinum agents is effective for intracranial immature teratomas.4 A previous case of intramedullary immature teratoma gained near-total resection without adjuvant therapy. Unfortunately, rapid recurrence in situ was noted on 8th month follow-up MRI.1 In the present case, adjuvant local radiotherapy was performed after the first surgery, and, no recurrence was found in the previous operative site, although metastatic recurrence appeared. After the second operation, radio- and chemotherapy were applied, which made the patient free from the tumor growth. It is presumed that a small malignant focus was disseminated by cerebrospinal fluid before or during the surgery. Generally speaking, immature teratomas usually demonstrate malignant features, and they can recur as a different histological subtype like ours. We agree with the opinion proposed by Schild et al.5 and Allsopp et al.2 that radiotherapy may be considered for immature and irradition fields can be designed to include only the primary tumor, but if the teratoma shows any other malignant histological features or germ cell elements, radiotherapy should be employed to the neural axis even if apparently totally excised. Together with these limited two cases, it is plausible that irradiation to the whole spine and a boost to the local area were favored in terms of immature teratoma of high grade. However, for recurrent tumors, salvage therapy including radiation therapy in combination with chemotherapy is indicated.6

As this tumor is very rare, its natural history is not well known. The present case, herein, although treated by gross total resection and local radiotherapy, still endured metastatic recurrence by way of the cerebrospinal fluid dissemination and then was referred to combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy after the second operation. We are still pessimistic about the patient because of the failure of normal levels of the tumor marker, although no changes were observed on the 6-month follow-up MRI.

Conclusion

Immature teratoma located in the spinal cord of the adult patient is an extremely rare entity, but it should always be considered in the differential diagnosis. This case report aims to increase knowledge about the pathogenesis, imaging features and treatment. Although the prognosis is poor, total excision is the primary treatment modality and adjuvant therapy is indicated. Irradiation to the whole spine and a boost to the local area may be promising to free from metastatic malignant recurrence by cerebrospinal fluid dissemination.

References

Moon HJ, Shin BK, Kim JH, Kim JH, Kwon TH, Chung HS et al. Adult cervical intramedullary teratoma: first reported immature case. J Neurosurg Spine 2010; 13: 283–287.

Allsopp G, Sgouros S, Barber P, Walsh AR . Spinal teratoma: is there a place for adjuvant treatment? Two cases and a review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg 2000; 14: 482–488.

Tapper D, Lack EE . Teratomas in infancy and childhood. A 54-year experience at the Children's Hospital Medical Center. Ann Surg 1983; 198: 398–410.

Ogawa K, Toita T, Nakamura K, Uno T, Onishi H, Itami J et al. Treatment and prognosis of patients with intracranial nongerminomatous malignant germ cell tumors: a multiinstitutional retrospective analysis of 41 patients. Cancer 2003; 98: 369–376.

Schild SE, Haddock MG, Scheithauer BW, Marks LB, Norman MG, Burger PC et al. Nongerminomatous germ cell tumors of the brain. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1996; 36: 557–563.

Sawamura Y, Kato T, Ikeda J, Murata J, Tada M, Shirato H . Teratomas of the central nervous system: treatment considerations based on 34 cases. J Neurosurg 1998; 89: 728–737.

Acknowledgements

We all thank Mr Tai-li Li who helped us perform the immunochemistry and Mrs Jian-Li (pathologist) who helped us in distinguishing the tumor from other types of germ cell tumors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Z., Du, Y., Qi, H. et al. Cervical intramedullary immature teratoma with metastatic recurrence in an adult. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 1, 15006 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2015.6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2015.6