Abstract

Study design:

A retrospective observational study.

Objective:

To describe specificities of pregnancy in a traumatic spinal cord-injured (SCI) population managed by a coordinated medical care team involving physical medicine and rehabilitation (PMR) physicians, urologists, infectious diseases' physicians, obstetricians and anaesthesiologists.

Setting:

NeuroUrology Department in a University Hospital, France.

Methods:

All consecutive SCI pregnant women managed between 2001 and 2014 were included. A preconceptional consultation was proposed whenever possible. Obstetrical and urological outcomes, delivery mode and complications were reported.

Results:

Overall, thirty-seven pregnancies in 25 women, of a mean age of 32±4 years, were included. Thirty-five children were born alive (three miscarriages, a twin pregnancy) without complications except for a case of neonatal respiratory distress in premature twins born at 33 weeks. The mean birth weight was 2979±599 g. Twenty-one (57%) pregnancies benefited from preconceptional care. A weekly oral cyclic antibiotic programme was prescribed in 28 (75%) pregnancies. The main complications during pregnancy included pyelonephritis (30%), lower urinary tract infections (UTI) (32%), pressure sores (8.8%) and prematurity (12% deliveries before 37 weeks, with only one delivery before 36 weeks). Two patients suffered from autonomic dysreflexia, one with serious complication (brain haematoma). Caesarean sections were performed for 68% of deliveries (23/34) to prevent syringomyelia deterioration (n=10), stress urinary incontinence aggravation (n=3) or for obstetrical reasons (n=7).

Conclusions:

Mothers’ and infants’ outcomes were satisfying after pregnancy in SCI women, but required many adjustments. Pregnancy must be prepared by a preconceptional consultation, and managed by a multidisciplinary team involving specialists of neurological disability and pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) has been reported to have an incidence of 1200 new cases per year in France (19.4 new cases per million inhabitants) and a prevalence of 50 000.1 Trauma represents more than 50% of causes of SCI. Moreover, 50% of SCI occurs in patients aged between 15 and 25 years, with 15–20% being women.2 Fertility ability in women is not reduced after SCI.3, 4 However, the fertility rate per woman is lower compared with that in the general population.4, 5

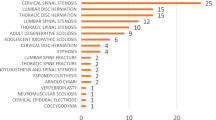

A few studies, presented in Table 1 (non-exhaustive list), have assessed the issue of pregnancy among SCI patients (many retrospective series, one small prospective observational study, two reviews).

The congenital malformation rate is not higher than that in the general population.3, 4 Neonatal mortality rate was not higher in the most recent studies.4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12 However, high rates of maternal and infant complications secondary to associated disabilities were reported. UTI was the most frequent complication in SCI pregnant women, as was present in most studies: 45–100% had lower UTI, 75% had repeated urinary infections4, 12 and 23–31% had pyelonephritis.8, 12 Urologic management was more challenging: one-fourth of the women reported the need to change their usual bladder management method during pregnancy, and 27–70% had to increase their number of intermittent catheterizations per day.4, 11

Autonomic dysreflexia was reported in 60% of pregnant women with spinal cord lesion above T6.8, 9 This very common complication in high SCI patients (85% of patients with injury at or above T6 (ref. 15)) can be a life-threatening situation: two cases of cerebral haemorrhage during labour were reported16, 17 and can appear specifically during labour.

The other complications were pressure sores (6–15%),4, 7, 8, 9, 10 worsening of spasticity (which may indicate the beginning of labour) and greater constipation.4, 5, 8 Few cases of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolisms were reported, despite cumulative risk for hypercoagulable state during pregnancy and relative immobility due to SCI.13

For a newborn, the main complications were prematurity (13–21%)4, 5, 9, 10 and low birth weight, and there were trends for more cases of fever, jaundice, or blood transfusion.4

The aim of this work was to describe specificities of pregnancy in a traumatic SCI population managed by coordinated medical care involving PMR physicians, obstetricians, anaesthesiologists and urologists.

Materials and methods

A retrospective observational study included all consecutive pregnant patients with a spinal cord injury managed in a University Hospital between March 2001 and September 2014. The following data were collected: neurological status, neuro-urological status before and during pregnancy, obstetrical and neonatal situation, and postpartum complications.

A preconceptional consultation was proposed as often as possible. The main point was neurogenic bladder management during pregnancy: usual follow-up (clinical, biological, urodynamic and radiologic assessment) and adaptation of care for pregnancy. For patients treated with intradetrusor injections of botulinum toxin, injections were stopped, and a minimum of 6 months between the last injection and the beginning of pregnancy was recommended. Anticholinergic drugs used in first intention were oxybutynin and/or trospium, because there are more data to support their safety during pregnancy18 than with the more recent anticholinergic drugs. A weekly oral cyclic antibiotic (WOCA) was prescribed to prevent urinary tract infection (UTI), according to Salomon’s protocol.6 During the preconceptional consultation, education on prevention of complications was imparted (risk for pressure sore, autonomic dysreflexia and prematurity) and spinal cord MRI was performed to search for a syringomyelia. Advice regarding the type of delivery, anaesthesia and follow-up was given. A review of all drugs used by the patients to control other disabilities (spasticity, pain and constipation) was conducted to reduce iatrogenicity. Patients were referred to a maternity unit with experience in neurological disability, and care coordination with obstetricians and anaesthetists was prepared.

Data are presented as mean±s.d. The χ2 test was used.

Results

Overall, 37 pregnancies in 25 SCI women, of mean age 32±4 years, were included. Fifteen women were followed for one pregnancy, 8 for 2 pregnancies and two for three pregnancies. Baseline characteristics of patients are summarised in Table 2.

Spinal cord injury was post-traumatic in 23 women (16 public highway accidents, 2 ski accidents, 2 parachute accidents, one climbing accident, one ballistic trauma and one unknown) and secondary to herniated disc in 2 women. The average length between spinal cord injury and beginning of pregnancy was 10±5 years. There was no pressure sore, nor was an intrathecal baclofen pump used to treat spasticity, in this population.

All kidney ultrasounds were normal except for one with renal lithiasis. Mean creatinine clearance, measured with 24-h urine collection, was 105±32 ml min−1 (from 52 to 158 ml min−1). There were 24% women with underactive or normal bladder and 76% with overactive bladder, controlled or not by anticholinergic, all using chronic intermittent catheterization (CIC). Fifteen patients were treated with detrusor injection of botulinum toxin before pregnancy. The delay between the last injection and beginning of pregnancy ranged from 0 to 120 months. On the basis of clinical criteria (perfect continence) and urodynamic test (low-pressure storage below 40cm H2O), there were 54% women with well-balanced bladder and 30% with unbalanced bladder before pregnancy (data were missing for 16%).

All patients were followed up by the NeuroUrology Department (involving PMR and urologists), an infectious diseases' physician and obstetric team, but only 57% benefited from preconceptional care. A WOCA programme was prescribed in 75% of pregnancies. During pregnancy, none of the patients needed to change the usual bladder management method; there were 52% with clinically well-balanced bladder and 24% with clinically unbalanced bladder (urine leakage, more frequent CIC and more voiding dysfunction for women voiding spontaneously). Data were missing for 24%.

Thirty-five children were born alive (there were three miscarriages and a twin pregnancy) without complications except for two cases of neonatal respiratory distress in a context of prematurity at 33 weeks (twins). Evolution was favourable with neonatal resuscitation care for the twins (ventilator weaning in 8 h), and there was no early neonatal complication in the other children. The mean birth weight was 2979±599 g.

Antenatal complications, perinatal outcome and postpartum complications are summarised in Table 3. The main complications during pregnancy were pyelonephritis (30%) and lower UTI (32%), sometimes with recurrent infections. There was no relation between WOCA programme use and urinary infection, with or without fever (Table 4). The other complications were three miscarriages (2 during the first trimester and one at 21 weeks, all undetermined causes), prematurity (12% of deliveries before 37 weeks, with only one delivery before 36 weeks) and pressure sores (8.8%). Anaesthesia during labour was given to all patients with a spinal injury level at or above T6, mainly by means of an epidural catheter, which was maintained for 24–48 h, to prevent autonomic dysreflexia. Only two patients (15% of deliveries with SCI at or above T6) suffered from autonomic dysreflexia: before delivery and during postpartum in one, and during postpartum in the other patient with a serious complication (brain haematoma). Caesarean sections were performed for 68% of deliveries (23/34) to prevent syringomyelia deterioration (n=10) or stress urinary incontinence aggravation (n=3), or for obstetrical reasons (n=7).

The most serious postpartum complication was a frontal brain haematoma, revealed by a mild aphasia three days after a caesarean section in a patient with autonomic dysreflexia despite prolonged epidural anaesthesia of 48 h, but with a too early decrease in the dosage of anaesthetics. Neurologic outcome was favourable. Usual bladder management method was preserved postpartum.

Discussion

This retrospective observational study reports a consecutive series of 37 pregnancies in 25 SCI patients. Despite some complications as in previous studies (pyelonephritis, lower UTI, dysreflexia and pressure sores), mothers' and infants' outcomes were satisfying: the prematurity rate was low and there were no neonatal complications, except for a twin pregnancy born at 33 weeks.

The UTI rate was low (32%) compared with that in other studies (45 to 100%), but the pyelonephritis rate was still high (30%). There were two different contexts to explain these eleven cases of pyelonephritis (all had overactive detrusor muscle and were using a CIC): half happened in patients with a neurological bladder that was well monitored but with very high risks, especially with botulinum toxin discontinuation for pregnancy, or in patients already under a double anticholinergic drug regimen. The five other pyelonephritis cases were probably favoured by an overactive bladder that was poorly treated (patients with poor compliance to treatment or follow-up). These urinary infections explain in large part the 12% prematurity, which remains low compared with that in other studies (13–21%),4, 5, 9, 10 and without neonatal complications except for the twin pregnancy.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is frequent in patients using CIC (70%), but is usually with no consequence when low-pressure storage and complete voiding are obtained, and does not require preventive treatment by chronic administration of antibiotics aside from during pregnancy.19 However, UTI are the most frequent complication in this population.20 The safety and efficacy of a WOCA strategy to prevent UTI in spinal cord injury was described by Salomon.21 During pregnancy, the risk for UTI associated with asymptomatic bacteriuria increases. It explains the recommendation for screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in patients without a neurogenic bladder to prevent pyelonephritis, which can initiate preterm labour and delivery.22 During pregnancy in SCI women using CIC, the diagnosis and prevention of UTI are hazardous because asymptomatic bacteriuria is frequent. A recent prospective study of six SCI pregnant women under WOCA showed a significant reduction in UTI and antibiotic consumption with no severe adverse events.6 In our study, a WOCA programme was prescribed in 75% of pregnancies, but with a large heterogeneity at the start of treatment (before or during pregnancy, sometimes late). Patients were included from the time of first medical contact in the NeuroUrology or Infectious Diseases Department, regardless of the pregnancy term. This treatment heterogeneity can explain the absence of relation found between WOCA programme use and urinary infection, unlike a recent retrospective study of 20 pregnancies.11 A larger-scale prospective study is mandatory to evaluate WOCA efficiency and to propose recommendations for SCI pregnant women.

Few data are available on botulinum toxin use during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Its use is contraindicated during these periods, and for safety a six-month delay was proposed between last injection and beginning of pregnancy. Botulinum toxin injections are planned during the first half of the cycle for women of childbearing age, with beta-HCG assay negative. Despite these precautions, botulinum toxin has been injected in one patient at the very start of pregnancy, when she did not know that she was pregnant. There was no effect on the foetus during pregnancy or during the neonatal period. Literature data on botulinum toxin use during pregnancy are reassuring, without any foetal or neonatal toxicity reported.23

Among the five pregnancies with augmentation cystoplasty, all under WOCA, there was one miscarriage and two pyelonephritis with upper tract obstruction requiring double-J ureteric stent for one and some lower UTIs. The pregnancy did not affect the renal function. These results are consistent with those in another study of 20 pregnant women with treated and reconstructed congenital urinary tract abnormalities, including 13 augmentation cystoplasty: 52% UTI and 10% upper tract obstructions.24 The mechanism proposed to explain upper tract obstruction during pregnancy was the increase in foetal pressure on the less robust neobladder. Interdisciplinary cooperation between urologists and obstetricians was stressed in case of caesarean section for women with augmentation cystoplasty, even if there were no postoperative complications in this study.24

A high rate of caesarean section (68%) was realized in this study, with more than half for neurologic reasons, in comparison to the general population (21% in France in 2010)25 and to the other studies (22–67%).4, 5, 8, 9, 10 It is well known that vaginal delivery is possible even for paraplegia and tetraplegia patients.7, 26 However, some neurologic cases have discussed the risk of worsening of syringomyelia or urinary stress incontinence by straining during the second stage of labour. Many cases of elective caesarean sections were reported in patients with congenital or post-traumatic syringomyelia,27, 28, 29 which leads to a consensus for caesarean section in the case of syringomyelia.30 However, a successful operative vaginal delivery without voluntary maternal expulsive efforts in a patient with syringomyelia was documented, without postpartum complication.31 In our study, all patients with syringomyelia underwent a caesarean section, which explains the high rate of caesarean section. The elective caesarean section in patients with neurologic sphincter failure to prevent worsening of urinary or faecal incontinence is further discussed. This strategy was reported for other causes of sphincter failure (bladder extrophy),32 but is not consensual (vaginal delivery is promoted in spina bifida).33 There is no recommendation for the mode of delivery in cauda equina syndrome; further work is required.

Anaesthesia was induced during labour in all patients with spinal injury at or above T6, mainly by means of epidural catheter, which was maintained for 24–48 h postpartum to prevent autonomic dysreflexia. Despite these precautions, one patient suffered a frontal brain haematoma, with a good neurologic outcome. Current recommendations promote epidural anaesthesia, early in labour and prolonged 24–48 h postpartum, to prevent and treat autonomic dysreflexia.26, 34, 35 The optimum dosage and duration of drugs administered by means of a epidural catheter are still under discussion. Some authors suggest placing the epidural catheter two or three weeks before the date of predicted childbirth,36 but others do not recommend it because of the risk of infection or catheter displacement.34 Several measures associated could also prevent autonomic dysreflexia (limited pelvic floor examination, avoiding speculum and prevention of bladder distension). Labour, delivery and postpartum are particularly potent stimuli to the development of autonomic dysreflexia, even for people with no previous history of autonomic dysreflexia.35 High SCI women should be referred for anaesthesia consultation early during pregnancy to prepare an appropriate plan for labour management. Anaesthetists, obstetricians, midwife and nurses who will take care of these patients should be trained in autonomic dysreflexia issues.

Conclusion

This observational study reports a consecutive series of 37 pregnancies in 25 SCI patients. Despite some complications as in previous studies, mothers' and infants' outcomes were satisfying: low prematurity rate and no neonatal complication except for twin pregnancy born at 33 weeks. Pregnancy in SCI women requires many adjustments (adaptation of neurogenic bladder management, prevention of autonomic dysreflexia by prolonged epidural anaesthesia and choice of the mode of delivery). Pregnancy must be prepared by a preconceptional consultation, and managed by a multidisciplinary team involving specialists of neurological disability and pregnancy to provide the best care for mothers and infants.

Data Archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Guide Affectation de Longue Durée—Paraplégie (lésions médullaires). Haute Autorité de Santé; 2007 Juillet.

Bedbrook G . The Care and Management of Spinal Cord Injuries. Springer Verlag: New York, NY, USA. 1981, p. 22.

Göller H, Paeslack V . Our experiences about pregnancy and delivery of the paraplegic woman. Paraplegia 1970; 8: 161–166.

Jackson AB, Wadley V . A multicenter study of women’s self-reported reproductive health after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1420–1428.

Charlifue SW, Gerhart KA, Menter RR, Whiteneck GG, Manley MS . Sexual issues of women with spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 192–199.

Salomon J, Schnitzler A, Ville Y, Laffont I, Perronne C, Denys P et al. Prevention of urinary tract infection in six spinal cord-injured pregnant women who gave birth to seven children under a weekly oral cyclic antibiotic program. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis 2009; 13: 399–402.

Robertson DN, Guttmann L . The paraplegic patient in pregnancy and labour. Proc R Soc Med 1963; 56: 381–387.

Baker ER, Cardenas DD, Benedetti TJ . Risks associated with pregnancy in spinal cord-injured women. Obstet Gynecol 1992; 80: 425–428.

Cross LL, Meythaler JM, Tuel SM, Cross AL . Pregnancy, labor and delivery post spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 890–902.

Westgren N, Hultling C, Levi R, Westgren M . Pregnancy and delivery in women with a traumatic spinal cord injury in Sweden, 1980-1991. Obstet Gynecol 1993; 81: 926–930.

Galusca N, Charvier K, Courtois F, Rode G, Rudigoz RC, Ruffion A . Antibioprophylaxy and urological management of women with spinal cord injury during pregnancy. Progres En Urol J Assoc Francaise Urol Soc Francaise Urol 2015; 25: 489–496.

Guerby P, Vidal F, Bayoumeu F, Parant O . Paraplegia and pregnancy. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2015; 45: 270–277.

Baker ER, Cardenas DD . Pregnancy in spinal cord injured women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77: 501–507.

Pannek J, Bertschy S . Mission impossible? Urological management of patients with spinal cord injury during pregnancy: a systematic review. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 1028–1032.

Hughes SJ, Short DJ, Usherwood MM, Tebbutt H . Management of the pregnant woman with spinal cord injuries. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1991; 98: 513–518.

Abouleish E . Hypertension in a paraplegic parturient. Anesthesiology 1980; 53: 348.

McGregor JA, Meeuwsen J . Autonomic hyperreflexia: a mortal danger for spinal cord-damaged women in labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985; 151: 330–333.

Edwards JA, Reid YJ, Cozens DD . Reproductive toxicity studies with oxybutynin hydrochloride. Toxicology 1986; 40: 31–44.

Reid G . Potential preventive strategies and therapies in urinary tract infection. World J Urol 1999; 17: 359–363.

Esclarín De, Ruz A, García Leoni E, Herruzo Cabrera R . Epidemiology and risk factors for urinary tract infection in patients with spinal cord injury. J Urol 2000; 164: 1285–1289.

Salomon J, Denys P, Merle C, Chartier-Kastler E, Perronne C, Gaillard J-L et al. Prevention of urinary tract infection in spinal cord-injured patients: safety and efficacy of a weekly oral cyclic antibiotic (WOCA) programme with a 2 year follow-up—an observational prospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 57: 784–788.

Vazquez JC, Villar J . Treatments for symptomatic urinary tract infections during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003; 4: CD002256.

Morgan JC, Iyer SS, Moser ET, Singer C, Sethi KD . Botulinum toxin A during pregnancy: a survey of treating physicians. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77: 117–119.

Greenwell TJ, Venn SN, Creighton S, Leaver RB, Woodhouse CRJ . Pregnancy after lower urinary tract reconstruction for congenital abnormalities. BJU Int 2003; 92: 773–777.

Blondel B, Kermarrec M . Les naissances en 2010 et leur évolution en 2003. INSERM-U.953, mai.

Greenspoon JS, Paul RH . Paraplegia and quadriplegia: special considerations during pregnancy and labor and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1986; 155: 738–741.

Roelofse JA, Shipton EA, Nell AC . Anaesthesia for caesarean section in a patient with syringomyelia. A case report. South Afr Med J Suid-Afr Tydskr Vir Geneeskd 1984; 65: 736–737.

Daskalakis GJ, Katsetos CN, Papageorgiou IS, Antsaklis AJ, Vogas EK, Grivachevski VI et al. Syringomyelia and pregnancy-case report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2001; 97: 98–100.

Margarido C, Mikhael R, Salman A, Balki M . Epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery in a patient with post-traumatic cervical syringomyelia. Can J Anaesth J Can Anesth 2011; 58: 764–768.

Tourbah A, Lyon-Caen O . Maladies neurologiques et grossess. In: Encycl Méd Chir (Elsevier, Paris), Gynécologie/Obstétrique 2000; S-046-B-10; Neurologie 2000; 17-163-A-10: 9.

Parker JD, Broberg JC, Napolitano PG . Maternal Arnold-Chiari type I malformation and syringomyelia: a labor management dilemma. Am J Perinatol 2002; 19: 445–450.

Body G, Lansac J, Lanson Y, Berger C . Exstrophy of the bladder and pregnancy. J Gynecol Obstetr Biol Reprod 1984; 13: 549–555.

Visconti D, Noia G, Triarico S, Quattrocchi T, Pellegrino M, Carducci B et al. Sexuality, pre-conception counseling and urological management of pregnancy for young women with spina bifida. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2012; 163: 129–133.

Rezig K, Diar N, Benabidallah D, Khodja A, Saint-Leger S . Paraplegia and pregnancy: anaesthesic management. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2003; 22: 238–241.

Crosby E, St-Jean B, Reid D, Elliott RD . Obstetrical anaesthesia and analgesia in chronic spinal cord-injured women. Can J Anaesth J Can Anesth 1992; 39: 487–494.

Kobayashi A, Mizobe T, Tojo H, Hashimoto S . Autonomic hyperreflexia during labour. Can J Anaesth J Can Anesth 1995; 42: 1134–1136.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Le Liepvre, H., Dinh, A., Idiard-Chamois, B. et al. Pregnancy in spinal cord-injured women, a cohort study of 37 pregnancies in 25 women. Spinal Cord 55, 167–171 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.138

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.138

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of sexual reproductive health needs of women with spinal cord injury in Tehran, Iran

Sexuality and Disability (2022)

-

Childbirth and motherhood in women with motor disability due to a rare condition: an exploratory study

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2021)

-

Outcomes of pregnancy and delivery in women with continent lower urinary tract reconstruction: systematic review of the literature

International Urogynecology Journal (2021)

-

Vaginal delivery is safely achieved in pregnancies complicated by spinal cord injury: a retrospective 25-year observational study of pregnancy outcomes in a national spinal injuries centre

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2020)

-

Guideline for the management of pre-, intra-, and postpartum care of women with a spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2020)