Abstract

Study design:

Review article.

Objectives:

To review the literature regarding treatment approaches in cases of gunshot wounds (GSWs) affecting the spine.

Setting:

Brazil.

Methods:

Narrative review of medical literature.

Results:

GSWs are an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality. Most patients with spinal GSW have complete neurological deficit. The injury is more common in young men and is frequently immobilizing. The initial approach should follow advanced trauma life support, and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be initiated immediately, especially in patients with perforation of the gastrointestinal tract. The indications for surgery in spinal GSW are deterioration of the neurologic condition in a patient with incomplete neurological deficit, the presence of liquor fistula, spinal instability, intoxication by the metal from the bullet or risk of bullet migration.

Conclusion:

Surgical treatment is associated with a higher complication rate than conservative treatment. Therefore, the surgeon must know the treatment limitations and recognize patients who would truly benefit from surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Because of the increasing violence in urban areas, gunshot wounds (GSWs) are an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the population, especially among young people (Table 1).1, 2, 3, 4 The incidence of penetrating injuries to the spine has increased lately,5 and they cause 13–17% of all spine injuries.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 The incidence of spinal cord lesions caused by gunshots varies considerably, depending on the country, ranging from 13 to 44%. In some series, GSWs are the most common cause of spinal cord lesions, followed by traffic accidents; however, in others the order is the reverse.6, 12, 13, 14, 15

Assaults and arguments represent the main motivation for gunshots among civilians, whereas accidental causes are rare.1 A study undertaken in two Brazilian state capitals showed that GSW was the cause of 17–30% of all hospital admissions for external causes. Of these, spinal cord lesions represented 90% of the admissions, and 80% of patients developed paraplegia or quadriplegia.2

These victims are usually young people under the age of 30 years, male and of low socioeconomic status, and many suffer from neurological deficits because of the spinal cord lesions.1, 2, 3, 4, 11, 12, 16 As noted, most patients are male, with the frequency of male victims of GSW in the spine varying from 78 to 94% in the literature (Table 2).3, 11, 17, 18, 19

Most patients with GSW in the spine have complete spinal cord injury.3 Some studies show that the location of the lesion determines the deficit, so that cervical lesions lead to complete neurological deficits in ∼70% of the cases,20, 21 whereas lesions of the cauda equina and at the lumbosacral level are incomplete in 70% of cases.9, 22 The main prognostic factor considered for recovery is the initial neurological status23—that is, patients with incomplete deficit have superior functional prognoses compared with those initially evaluated as presenting complete deficits. The functional recovery in patients with neurological deficits resulting from GSW is usually worse than that of traffic accident victims or those with stab wounds.24 The period of follow-up to consider the functional status as definitive is a matter of controversy in the literature, varying from 2 weeks to 6 months.16, 19, 24, 25, 26, 27 Mortality in patients suffering from GSW increases with the severity of neurological deficit.16

Historical perspective

In Ancient Egypt, Imhotep (1700 BCE) reported traumatic injuries of the spine.25 Galen (130–200 CE) showed that longitudinal spinal cord lesions do not cause serious functional damage while transverse lesions were associated with paraplegia related to the level of the lesion.27 Ambroise Paré (1557) left the first description of spinal cord injury caused by firearms. During the US Civil War, 642 cases of spinal GSW were reported.28 The use of antibiotics and changes in the surgical treatment of spine lesions, such as early surgery, debridement and applying of patches were a milestone in World War II, greatly reducing the mortality of these patients.29

Ballistics

The kinetic energy of an object depends on its mass and velocity (E=1/2mv2). Low-energy projectiles, fired from pistols and revolvers, travel at 1000–2000 feet per second (f.p.s.). Projectiles traveling at 2000–3000 f.p.s. are high-energy bullets fired from rifles and military weapons.30 Gunshot accidents in the civil population, therefore, involve low-energy firearms, and the tissue damage occurs mainly because of the impact from the projectile mass.11 According to Miller, 0.22, 0.25, 0.32 and 0.38 caliber handguns are indeed the most common;30 however, the incidence of high-energy GSW in the civil population has increased.31 However, because of the difference between high- and low-energy weapons, treatment protocols designed in war situations should not be extrapolated to the normal routine in peaceful regions, as we explain below.3

The projectile velocity determines the wounding potential of the weapon;32 however, the energy is not the only factor contributing to tissue damage: the physical properties of the bullets, such as design and fragmentation, also determine lesion characteristics.33 Caseless ammunition tends to spread and produce a large, circumferential harm. There are, therefore, three mechanisms of tissue damage: the direct impact of the bullet, the pressure of shock waves and the temporary cavitation.11, 12, 30, 34 Mirovsky et al.35 verified this, observing that neurological deficits following GSW in the spine can occur even without direct trauma or violation of the spinal canal.

Classification of gunshot injuries in the spine

The spinal injuries caused by GSW may be classified as type I: transfixing (when small fragments are found inside the canal); type II: intracanal (when the whole projectile is inside the canal); or type III: intervertebral lesions (when the bullet is inside the intervertebral disc space; Figure 1). Type III injuries are subdivided into (A) spinal lesion not associated with perforation of abdominal viscera or (B) injury with perforation of abdominal organs. In most cases of GSW, the injury is transfixing, and only little fragments (altogether <50% of the projectile) remain in the spinal canal. In the second place come cases in which the projectile is lodged inside the canal3, 4, 36 (Table 3), comprising 20.4% of cases.

Evaluation of a gunshot injury in the spine

The evaluation of a patient with a GSW should first follow the techniques of basic life support known as ‘ABCDE’ (airway, breathing, circulation, disability and exposure).3 Only after this is completed should the patient be cared for regarding the spinal lesion (Figure 2). If possible, useful information should be collected, such as the direction of the shot, type of weapon or bullet, the proximity of the discharging gun and the number of shots. A rigid collar must be placed to protect the cervical spine until radiographs are complete and properly analyzed.37 However, long and unnecessary immobilization potentially brings a negative prognosis and even mortality.38, 39

The patient should be undressed and moved carefully in search of bullet holes. As already stated, most GSWs are transfixing.3 The bullet holes must be differentiated as entry (with regular and clean edges) or exit (appearance of small explosion) holes. There should not be a deep digital exploration of holes, especially in the abdominal region. Physical examination of the spine should follow, as in other types of trauma in this region, with palpation of all the spinous processes in search of crepitus, gaps and pain points and with a complete neurological examination.

Table 2 shows data from the literature about the distribution of lesions according to spinal levels.3, 11, 17, 18, 19 Special concerns for each region are detailed below.

Cervical spine gunshot injuries

Cervical GSWs most likely result in complete rather than incomplete neurological deficit.11 Injuries in the cervical spine are frequently associated with airway lesions that may require emergency intubation,40, 41 and they are mostly stable; therefore, there is no reason to delay salvage procedures by taking radiographs.38, 42, 43, 44 The reason for the stability of cervical lesions from GSW compared with closed traumas is that the ligamentous complex remains intact in most cases, despite the anterior spine destruction.45 Indeed, the main causes of death from penetrating trauma to the neck are vascular injuries.34 Pulsatile bleeding from the neck should raise the suspicion of injury of the carotid or vertebral arteries. Injuries of the larynx and esophagus must be identified and assessed because of association with infections. There is still a significant rate of lung infection associated with cervical spine GSW.16 Figure 3 shows an algorithm for the clinical approach in cases of penetrating injuries to the cervical spine.

Thoracic spine gunshot injuries

The thorax is the region most frequently affected by GSW (Table 2).3, 11, 17, 18, 19 Special attention should be given to the various organs and structures that are at risk in the projectile path until reaching the spine. In the chest, the heart, lungs and great vessels may be damaged. In the abdomen, lesions of the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in the colon, must be recognized and treated because of the high risk of infection.20, 46, 47, 48 Barros Filho et al.,3 in a review of 1000 cases of spine GSW, showed an incidence of 18.4% of injuries associated with spinal trauma, and hemopneumothorax was the most frequent (9.7%). Transfixing trauma was the most common type. Literature review also shows that abdominal lesions and hemopneumothorax are the most prevalent (24% and 20%, respectively) associated injury,11 and that transfixing lesions are the most common.3, 36 The incidence of lesions to vital organs is 20%.49

Lumbosacral spine gunshot injuries

The main concern in cases of lumbosacral spine GSW in the acute phase should be possible bleeding, which sometimes endangers the life of the patient. If identified, bleeding should be promptly treated with tamponade, exploration or embolization (the latter endangers the neural structures due to ischemia).50

Diagnostic imaging

Two orthogonal radiographs should be performed to diagnose fractures and locate the bullet or bullets. The stability of the spine can be assessed by dynamic radiographs (in flexion and extension); however, this imaging requires that the patient is awake and neurologically normal, which is easier a few days after the injury, when the pains and spasms decreased. Low-speed gunshots, the most common in civilian circumstances, usually do not cause spine instability.51

The need for radiograph exploration of the spine in search of fractures in cases of injuries to the head and face has been questioned in the literature. Some series have reported no spine fracture in association with shots taken against the skull.44, 52 Kihtir et al.43 reported 10% and 20% of cervical fractures in association with injuries to the jaw and orbit, respectively, and no fracture in the lower (mandibular) area. Thus, the need to X-ray the spine in search of fractures in patients with skull GSW is not well established.

Once a spine fracture is detected, computed tomography is the next test to perform, allowing for better location of the bullet, definition of bone damage and the presence of intracanal fragments. In addition, computed tomography allows for evaluation of instability.53 The use of magnetic resonance imaging is controversial. Despite its advantage of better delineation of soft tissue and nerve elements,54, 55 there is a potential risk of migration of the bullet because of the magnetic field, which can cause or worsen the neurological deficit. However, numerous studies have not confirmed this fact.56 It has been stated that a low-energy, copper-covered bullet does not present magnetic properties that would lead to migration,57 but it is difficult to determine the quality of the projectile in the emergency room to make a decision about the indication of magnetic resonance imaging. Furthermore, patients undergoing magnetic resonance imaging typically complain of discomfort and, for this reason, the examination is often suspended.

Treatment

The initial approach of GSW should follow ATLS (advanced trauma life support) principles, addressing injuries with higher mortality risk, upper airway lesions in the face and neck, and injuries of great vessels. Exsanguination followed by hemothorax and pneumothorax is the main cause of death in patients injured by firearms. Lesions of abdominal viscera must be surgically dealt with, including abdominal cavity washing/cleaning and debridement of the wound. Fractures of long bones should be washed, debrided and fixed externally, and spinal injuries should be left for a second surgical procedure.

Medication treatment

Tetanus vaccination

The patient’s vaccination status must be checked. If there is any doubt about the last dose of antitetanus vaccine administered, vaccination should be performed while still in the emergency room.58

Antibiotics

Antibiotic therapy should be initiated immediately with broad-spectrum antibiotics in all cases for 48–72 h, especially in patients with perforation of the gastrointestinal tract, with high risk for infection (especially when the colon is affected, which presents a greater risk of infection than perforation of the stomach or small intestine). This type of injury is present in 23.7% of GSW of the spine. In these cases, exploratory laparotomy is recommended, with surgical lavage of the abdominal cavity with abundant saline after repair or bypass of the intestine for a loop or Hartman type colostomy.20, 59 The surgical removal of the bullet and bone debridement in the spine path are not considered necessary or effective in preventing infectious complications, and leaving the bullet lodged in the spine is not a risk factor for infection.8, 60 The administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics intravenously extended for 7–14 days reduces the rate of infection compared with administration for 48–72 h (Table 4).46, 48, 58

Septic complications such as osteomyelitis, meningitis, or intrathoracic or intra-abdominal abscess have catastrophic consequences and are difficult to treat, with poor therapeutic response.61 In our institute, all GSW affecting spinal bones receive immediate broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, and all cases are evaluated by the hospital infections committee. Usually, the choice is for teicoplanin, at a dose of 400 mg twice daily, and amikacin, 750 mg in one dose daily for 5 days. In cases with bowel perforation, we add metronidazole at a dosage of 500 mg, three times daily, for a period of 5–7 days.

Corticosteroids

The use of corticosteroids in high doses in patients with spinal cord injury has been advocated for many years. However, since the implementation of the National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study II (NASCIS-II) in 1990, several authors have questioned the use of high-dose methylprednisolone because of the risks of complications and side effects, with little relevant effects on neurological outcomes.

Several published studies have found no evidence for the use of high doses of methylprednisolone in patients with spinal cord injury.11 In patients injured by firearms, the NASCIS-II protocol failed too. Levy et al.19 retrospectively analyzed 236 cases, with 55 patients treated with adjuvant corticosteroids, compared with another group not receiving this treatment. The authors found no evidence to support the use of the medication. Simpson et al.62 analyzed 142 cases, using doses of 4–6 mg dexamethasone, every 4 h, and they also concluded that the use of this corticosteroid did not change the neurologic prognosis.

In Brazil, the Brazilian Medical Association published the Guideline Project, aiming to standardize the procedures in public and private medical institutions, as well as in teaching hospitals. The Guidelines state that the use of corticosteroids produces no benefit to the patient with spinal cord injury.63

Surgical treatment

Surgical treatment of GSW in the spine remains controversial. Many issues are discussed: decompressive laminectomy has been shown as ineffective for neurological recovery,11, 23 and the removal of the bullet may not be capable of reducing infection24, 45, 64 while, as discussed above, intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy for 7–14 days satisfactorily fulfills this role. The main evidence for recovery is in cases of incomplete deficits, especially in the lumbar region (cauda equina) in which the procedure is performed early.10, 11, 17, 65

The only absolute indication for surgery in spinal GSW is the presence of cutaneous or pleural liquor fistula or the presence of documented progression of the neurological deficit associated with compression of neural elements in imaging examinations.5 Laminectomy should be considered in patients with partial neurological deficit, especially those with cauda equina, with imaging showing involvement of the spinal canal by bone or metal fragments. The surgery should be performed in the first 24–48 h, provided that the potentially fatal injuries have been treated and the patient is clinically stable.11, 23, 61, 66, 67

Nevertheless, some studies in the military field show controversial results even in patients with incomplete neurological deficit. Stauffer et al.68 treated 79 patients with GSW with incomplete neurological deficit. Of these, 71% had some neurological improvements after surgery, whereas 76.5% of those who did not undergo surgical treatment also showed improvement. Yashon et al.69 and Heiden et al.66 presented similar results. Cybulski et al.67 compared patients undergoing surgery before and after 72 h and observed no statistical difference in neurologic improvement between the two groups. The recent literature supports decompression and removal of the projectile in cases of incomplete or progressive deficit.5

Another indication for surgery is spinal instability caused by associated fractures, observed in 10% of the cases.70 In contrast to blunt trauma, which has well-established criteria for instability, in penetrating trauma to the spine, any degree of curvature may represent an abnormal or translational instability. In these cases, the segments must be fixed and stabilized by means of instrumentation and fusion. Comminution of the vertebral body or posterior elements, with radiological evidence of deformity, can also result in segmental instability. Another important cause of instability is a wide decompressive laminectomy, also requiring fixation to prevent iatrogenic spinal deformities.24

In making a decision, the surgeon should keep in mind that surgical treatment is associated with a higher complication rate.11 The indications for surgery (Figure 4) should be as follows:

-

Neurological deterioration in a patient with incomplete deficit

-

Presence of externalized liquoric fistula (risk of meningitis)

-

Mechanical instability

-

Installed toxicity

-

Location of the bullet at risk for migration (inside the disk or intracanal)

-

Location of the bullet at risk of toxicity (articular or intracanal)

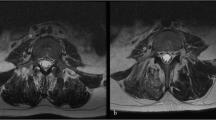

Imaging examinations of a male patient, aged 29 years, with a bullet lodged in T11, complete neurological deficit and with a liquoric fistula. (a) Initial radiographs evidencing the presence of the bullet. (b) Axial and sagittal cuts of the computed tomography imaging, better defining the position of the bullet and showing bone lesions and contact with the spinal canal. (c) Images obtained during surgery showing the removal of the projectile and the correction of the fistula.

Complications

Pain is probably the most common complication in the long term and is quite prevalent in cases of involvement of the cauda equina and conus medullaris.71 The removal of the bullet is not associated with the resolution of the pain.65 This situation is usually managed with administration of drugs, such as tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants such as amitriptyline or gabapentin.23, 62, 65, 71 The mechanism of tricyclic antidepressants in ameliorating neuropathic pain is not well understood; they probably reduce the pain by their unique ability to inhibit the presynaptic reuptake of biogenic amines, such as serotonin and noradrenaline. Other mechanisms may involve blockage of ion channel and n-methyl d-aspartate receptors.72 Anticonvulsants such as gabapentin and pregabalin have a moderate to large effect on improvement of pain relief, as shown in randomized controlled trials.73 Their action in neuropathic pain is not clear, either, however; they bind calcium channels and modulate calcium influx as well as influence GABAergic neurotransmission, and block new synapse formation, which may relieve pain.74 In refractory cases, surgical procedures, such as the ablation of the nociceptive root, can be performed.65, 71

Another problem related to the lodged bullet is metal toxicity, particularly from lead. Systemic intoxication by lead, also known as lead poisoning, plumbism or saturnism, is a rare but reported complication after GSW cases in which the bullet remains lodged in the spine.75, 76, 77, 78 Some factors are decisive for the occurrence of lead poisoning, and the location of the projectile is the main risk factor.79 When the bullet penetrates subcutaneous muscle or the bone, a fibrous capsule is formed, which prevents contact with body fluids or blood.75 When the bullet is inside the joint, the capsule is formed, but because of constant contact with the synovial fluid, the lead particles that are released can be reabsorbed into the bloodstream, resulting in clinical symptoms and laboratory signs. The joints most commonly affected by GSW are the hip and the knee. Other factors involving lead toxicity are exposure time and genetic predisposition. Because of a lower corrosion power of the cerebrospinal fluid compared with the synovial fluid, it is uncommon for intracanal projectiles to cause lead poisoning. Projectiles near the facet joints or intervertebral disc space, in turn, are more likely to cause the problem.80, 81, 82, 83

Lead poisoning can result in various clinical symptoms76 with an effect on laboratory examinations and with joint pain, anemia, peripheral paresthesia due to demyelination of the motor axon, abdominal complaints, headache, fatigue, signs of encephalopathy (such as memory loss), and attention deficit and behavioral alterations,53 and may even lead to death.84, 85 In fact, the clinical picture of lead poisoning is frequently undernoticed,53 as is the elevation of serum lead levels. Confirmation can be made by bone marrow biopsy, which reveals hematopoietic changes. Examination of serum lead levels should be requested at the beginning of treatment, again in 2 weeks, then monthly for 3 months, and finally at 1 year following the injury. Acceptable levels are <40 μg dl−1 in adults and <10 μg dl−1 in children.52, 86 Treatment with chelating agents should be started as soon as the problem is recognized, usually when serum levels of lead are >100 μg dl−1 or >50 μg dl−1 in symptomatic cases, followed by a plan to withdraw the bullet. The best-known chelating agents are edetate calcium disodium (that is, EDTA), dimercaprol and succimer.

Meningitis is a complication inherent to trauma, and surgical treatment is considered a risk factor.7, 62 Charcot arthropathy is a complication that has been described; however, it is uncommon following a GSW. The clinical picture consists of pain associated with progressive deformity in the affected level or below. The treatment is surgical stabilization.87, 88, 89 Neurogenic bladder and urinary tract infections are other common complications.11 Another possible complication is the migration of the projectile, which may or may not cause changes in neurological function.90

A special note about high-energy weapons

With the rise of organized crime and terrorist attacks, the incidence of attacks with high-energy weapons increases too. As mentioned earlier, the tissue destruction by high-energy projectiles is much worse than is found with low-energy GSW. Just as in low-energy GSW, however, decompressive laminectomy is not directly related to changes in the neurological status in these cases. The indications for surgery are different here, although, because the debridement of devitalized tissue decreases the prevalence of sepsis and secondary infections, with a low rate of secondary complications of the procedure.58 More studies addressing the issue of high-energy GSW in the civilian population, in our opinion, are necessary for us to address more properly the peculiarities of this type of injury.

Conclusions

GSWs in the spine are a frequent problem with a real impact on the population and on health system costs. Beyond conventional radiography, it is important to use computed tomography to better characterize bone lesions and the exact positioning of the projectile and fragments, to identify a possibly unstable lesion. With these data, we can determine whether there is any indication for a surgical procedure for removing the bullet. There should be a clear indication for surgical treatment because the conservative approach is safer.

References

Cook PJ, Lawrence BA, Ludwig J, Miller TR . The medical costs of gunshot injuries in the United States. JAMA 1999; 282: 447–454.

Associação das Pioneiras Sociais. Mapa da Morbidade por Causas Externas. Rede Sarah de Hospitais de Reabilitação. Available at http://www.sarah.br/paginas/prevencao/po/p-02_pesquisas.htm Accessed 29 January 2013..

de Barros Filho TEP, Oliveira RP, Barros EK, Von Uhlendorff EF, Iutaka AS, Cristante AF et alFerimento por projétil de arma de fogo na coluna vertebral: estudo epidemiológico [Gunshot wounds of the spine: epidemiological study]. Coluna 2002; 1. Available at www.plataformainterativa2.com/coluna/html/revistacoluna/volume1/ferimento_projetil.htm Accessed 29 January 2013..

Araújo Júnior FA, Heinrich CB, Cunha MLV, Veríssimo DCA, Rehder R, Pinto CAS et al. Traumatismo raquimedular por ferimento de projétil de arma de fogo: avaliação epidemiológica [Spinal cord trauma by a firearm projectile: epidemiological assessment]. Coluna/Columna 2011; 10: 290–292.

Kumar A, Pandey PN, Ghani A, Jaiswal G . Penetrating spinal injuries and their management. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine 2011; 2: 57–61.

Farmer JC, Vaccaro AR, Balderston RA, Albert TJ, Cotler J . The changing nature of admissions to a spinal cord injury center: violence on the rise. J Spinal Disord 1998; 11: 400–403.

Aarabi B, Alibaii E, Taghipur M, Kamgarpur A . Comparative study of functional recovery for surgically explored and conservatively managed spinal cord missile injuries. Neurosurgery 1996; 39: 1133–1140.

Lin SS, Vaccaro AR, Reisch S, Devine M, Cotler JM . Low-velocity gunshot wounds to the spine with an associated transperitoneal injury. J Spinal Disord 1995; 8: 136–144.

Chittiboina P, Banerjee AD, Zhang S, Caldito G, Nanda A, Willis BK . How bullet trajectory affects outcomes of civilian gunshot injury to the spine. J Clin Neurosci 2011; 18: 1630–1633.

Robertson DP, Simpson RK . Penetrating injuries restricted to the cauda equina: a restrospective review. Neurosurgery 1992; 31: 265–269 (discussion 269–270).

Sidhu GS, Ghag A, Prokuski V, Vaccaro AR, Radcliff KE . Civilian gunshot injuries of the spinal cord: a systematic review of the current literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471: 3945–3955.

Gur A, Kemaloglu MS, Cevik R, Sarac AJ, Nas K, Kapukaya A et al. Characteristics of traumatic spinal cord injuries in south-eastern Anatolia, Turkey: a comparative approach to 10 years' experience. Int J Rehabil Res 2005; 28: 57–62.

Mawson AR, Snelling L, Winchester Y, Biundo JJ Jr . 526 spinal cord injuries: experience of the Louisiana Rehabilitation Institute, 1965–1984. J La State Med Soc 1991; 143: 31–37.

Khella L, Stoner EK . 101 cases of spinal cord injury. 15-year follow-up study in a large city hospital. Am J Phys Med 1977; 56: 21–32.

Barros Filho TE, Taricco MA, Oliveira RP, Greve JMA, Santos LCR, Napoli MMM . Estudo epidemiológico dos pacientes com traumatismo da columa vertebral e déficit neurológico, internados no Instituto de Ortopedia e Traumatologia do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da USP [Epidemiological study of patients with spinal cord injuries and neurologic deficit, admitted in the Instituto de Ortopedia e Traumatologia do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo]. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med São Paulo 1990; 45: 123–126.

Azevedo-Filho HRC, Martins C, Carneiro-Filho GS, Azevedo R, Azevedo F . Gunshot wounds to the spine: study of 246 patients. Neurosurg Quart 2001; 11: 199–208.

le Roux JC, Dunn RN . Gunshot injuries of the spine—a review of 49 cases managed at the Groote Schuur Acute Spinal Cord Injury Unity. S Afr J Surg 2005; 43: 165–168.

Heary RF, Vaccaro AR, Mesa JJ, Northrup BE, Albert TJ, Balderston RA et al. Steroids and gunshot wounds to the spine. Neurosurgery 1997; 41: 576–583 (discussion 583–584).

Levy ML, Gans W, Wijesinghe HS, SooHoo WE, Adkins RH, Stillerman CB . Use of methylprednisolone as an adjunct in the management of patients with penetrating spinal cord injury: outcome analysis. Neurosurgery 1996; 39: 1141–1148 (discussion 1148–1149).

Romanick PC, Smith TK, Kopaniky DR, Oldfield D . Infection about the spine associated with low-velocity-missile injury to the abdomen. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1985; 67: 1195–1201.

Schneider RC, Webster JE, Lofstrom JE . A follow-up report of spinal cord injuries in a group of World War II patients. J Neurosurg 1949; 6: 118–126.

Haynes WG . Acute war wounds of the spinal cord. Am J Surg 1946; 72: 424–433.

Klimo P Jr, Ragel BT, Rosner M, Gluf W, McCafferty R . Can surgery improve neurological function in penetrating spinal injury? A review of the military and civilian literature and treatment recommendations for military neurosurgeons. Neurosurg Focus 2010; 28: E4.

Hammoud MA, Haddad FS, Moufarrij NA . Spinal cord missile injuries during the Lebanese civil war. Surg Neurol 1995; 43: 432–437 (discussion 437–442).

Guttmann SL . Spinal Cord Injuries: Comprehensive Management and Research 2nd edn (Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford. 1976).

Yashon D . Spinal Injury. Appleton: New York, NY, USA. 1978.

Ducker TB, Lucas JT, Wallace CA . Recovery from spinal cord injury. In: Weiss MH, (ed).. Clinical Neurosurgery. Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore. 1982 pp 495–513.

Sonntag VKH. History of degenerative and traumatic diseases of the spine. In: Greenblat SH, Epstein MH (eds).. A History of Neurosurgery in its Scientific and Professional Contexts. American Association of Neurological Surgeons: Park Ridge. 1997 pp 355–371.

Matson DM . The Treatment of Acute Compound Injuries of the Spinal Cord due to Missiles. Charles Thomas: Springfield. 1948.

Miller CA . Penetrating wounds of the spine. In: Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS, (eds).. Neurosurgery vol. 1. McGraw-Hill: San Francisco. 1985 pp 1746–1748.

Turgut M, Ozcan OE, Güçay O, Sağlam S . Civilian penetrating spinal firearm injuries of the spine. Results of surgical treatment with special attention to factors determining prognosis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1994; 113: 290–293.

DeMuth WE Jr . Bullet velocity and design as determinants of wounding capability: an experimental study. J Trauma 1966; 6: 222–232.

Galano E, Gélis A, Oujamaa L, Dutray A, Pelissier J, Dupeyron A . An atypical ballistic traumatic cauda equina syndrome with a positive outcome. Focus on prognostic factors. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2009; 52: 687–693.

Rao PM, Ivatury RR, Sharma P, Vinzons AT, Nassoura Z, Stahl WM . Cervical vascular injuries: a trauma center experience. Surgery 1993; 114: 527–531.

Mirovsky Y, Shalmon E, Blankstein A, Halperin N . Complete paraplegia following gunshot injury without direct trauma to the cord. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005; 30: 2436–2438.

Waters RL, Adkins RH, Yakura J, Sie I . Profiles of spinal cord injury and recovery after gunshot injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1991; 267: 14–21.

Inaba K, Barmparas G, Ibrahim D, Branco BC, Gruen P, Reddy S et al. Clinical examination is highly sensitive for detecting clinically significant spinal injuries after gunshot wounds. J Trauma 2011; 71: 523–527.

Cornwall EE 3rd, Chang DC, Bonar JP, Campbell KA, Phillips J, Lipsett P et al. Thoracolumbar immobilization for trauma patients with torso gunshot wounds: is it necessary? Arch Surg 2001; 136: 324–327.

Connell RA, Graham CA, Munro PT . Is spinal immobilisation necessary for all patients sustaining isolated penetrating trauma? Injury 2003; 34: 912–914.

Fetterman BL, Shindo ML, Stanley RB Jr., Armstrong WB, Rice DH . Management of traumatic hypopharyngeal injuries. Laryngoscope 1995; 105: 8–13.

Mohamad I, Musa MY, Razaq AS . Acute upper airway obstruction secondary to gunshot injury splitting cervical vertebra. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2011; 40: 430–431.

Kupcha PC, An HS, Cotler JM . Gunshot wounds to the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1990; 15: 1058–1063.

Kihtir T, Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Nassoura Z, Leban S . Early management of civilian gunshot wounds to the face. J Trauma 1993; 35: 569–575 (discussion 575–577).

Kennedy FR, Gonzalez P, Beitler A, Sterling-Scott R, Fleming AW . Incidence of cervical spine injury in patients with gunshot wounds to the head. South Med J 1994; 87: 621–623.

Waters RL, Sie IH . Spinal cord injuries from gunshot wounds to the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; 408: 120–125.

Kumar A, Wood GW 2nd, Whittle AP . Low-velocity gunshot injuries of the spine with abdominal viscus trauma. J Orthop Trauma 1998; 12: 514–517.

Kihtir T, Ivatury RR, Simon R, Stahl WM . Management of transperitoneal gunshot wounds of the spine. J Trauma 1991; 31: 1579–1583.

Roffi RP, Waters RL, Adkins RH . Gunshot wounds to the spine associated with a perforated viscus. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989; 14: 808–811.

Jacobson SA, Bors E . Spinal cord injury in Vietnamese combat. Paraplegia 1970; 7: 263–281.

Naude GP, Bongard FS . Gunshot injuries of the sacrum. J Trauma 1996; 40: 656–659.

Aryan HE, Amar AP, Ozgur BM, Levy ML . Gunshot wounds to the spine in adolescents. Neurosurgery 2005; 57: 748–752.

Chong CL, Ware DN, Harris JH Jr. . Is cervical spine imaging indicated in gunshot wounds to the cranium? J Trauma 1998; 44: 501–502.

Rentfrow B, Vaidya R, Elia C, Sethi A . Lead toxicity and management of gunshot wounds in the lumbar spine. Eur Spine J 2013; 22: 2353–2357.

Bashir EF, Cybulski G, Chaudhri K, Choudhury AR . Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in the evaluation of penetrating gunshot injury of the spine. Case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993; 18: 772–773.

Ebraheim NA, Savolaine ER, Jackson WT, Andreshak TG, Rayport M . Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of a gunshot wound to the cervical spine. J Orthop Trauma 1989; 3: 19–22.

Finitsis S, Falcone S, Green BA . MR of the spine in the presence of metallic bullet fragments: is the benefit worth the risk? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999; 20: 354–356.

Kafadar AM, Kemerdere R, Isler C, Hanci M . Intradural migration of a bullet following spinal gunshot injury. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 326–329.

Bono CM, Heary RF . Gunshot wounds to the spine. Spine J 2004; 4: 230–240.

Quigley KJ, Place HM . The role of debridement and antibiotics in gunshot wounds to the spine. J Trauma 2006; 60: 814–819 (discussion 819–820).

Velmahos G, Demetriades D . Gunshot wounds of the spine: should retained bullets be removed to prevent infection? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1994; 76: 85–87.

Benzel EC, Hadden TA, Coleman JE . Civilian gunshot wounds to the spinal cord and cauda equina. Neurosurgery 1987; 20: 281–285.

Simpson RK Jr, Venger BH, Narayan RK . Treatment of acute penetrating injuries of the spine: a retrospective analysis. J Trauma 1989; 29: 42–46.

Sociedade Brasileira de Ortopedia e Traumatologia. Sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia. Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia. Lesões traumáticas da coluna cervical (cervical alta – C1 e C2, e cervical baixa – C3 a C7). Projeto Diretrizes. São Paulo: Associação Médica Brasileira e Conselho Federal de Medicina; 2007. Available at: http://www.projetodiretrizes.org.br/7_volume/32-Lesoes_Trau.Col.Cerv.pdf Accessed 14 February 2013..

Velmahos GC, Degiannis E, Hart K, Souter I, Saadia R . Changing profiles in spinal cord injuries and risk factors influencing recovery after penetrating injuries. J Trauma 1995; 38: 334–337.

Waters RL, Adkins RH . The effects of removal of bullet fragments retained in the spinal canal. A collaborative study by the National Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991; 16: 934–939.

Heiden JS, Weiss MH, Rosenberg AW, Kurze T, Apuzzo ML . Penetrating gunshot wounds of the cervical spine in civilians. Review of 38 cases. J Neurosurg 1975; 42: 575–579.

Cybulski GR, Stone JL, Kant R . Outcome of laminectomy for civilian gunshot injuries of the terminal spinal cord and cauda equina: review of 88 cases. Neurosurgery 1989; 24: 392–397.

Stauffer ES, Wood RW, Kelly EG . Gunshot wounds of the spine: the effects of laminectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1979; 61: 389–392.

Yashon D, Jane JA, White RJ . Prognosis and management of spinal cord and cauda equina bullet injuries in sixty-five civilians. J Neurosurg 1970; 32: 163–170.

Water RL, Hu SS . Penetrating injuries of the spinal cord: stab and gunshot injuries. In: Frymoyer JW, (ed).. The Adult Spine: Principles and Practice. Raven Press: New York, NY, USA. 1991 pp 815–826.

Spaić M, Petković S, Tadić R, Minić L . DREZ surgery on conus medullaris (after failed implantation of vascular omental graft) for treating chronic pain due to spine (gunshot) injuries. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1999; 141: 1309–1312.

Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS . Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2005; 96: 399–409.

Guy S, Mehta S, Leff L, Teasell R, Loh E . Anticonvulsant medication use for the management of pain following spinal cord injury: systematic review and effectiveness analysis. Spinal Cord 2014; 52: 89–96.

Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, Aldington D, Cole P, Rice ASC et alAntiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia–an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; (11): CD010567.

Grogan DP, Bucholz RW . Acute lead intoxication from a bullet in an intervertebral disc space. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981; 63: 1180–1182.

Cristante AF, e Souza FI, Barros Filho TE, Oliveira RP, Marcon RM . dLead poisoning by intradiscal firearm bullet: a case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010; 35: E140–E143.

Linden MA, Manton WI, Stewart RM, Thal ER, Feit H . Lead poisoning from retained bullets. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Ann Surg 1982; 195: 305–313.

Cagin CR, Diloy-Puray M, Westerman MP . Bullets, lead poisoning and thyrotoxicosis. Ann Intern Med 1978; 89: 509–511.

Beazley WC, Rosenthal RE . Lead intoxication 18 months after a gunshot wound. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1984; 190: 199–203.

de Madureira PR, De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ . Lead poisoning after gunshot wound. Sao Paulo Med J 2000; 118: 78–80.

Costa RC, Stape CA, Suzuki I, Targa WHC, Batista MA, Bernabe AC et al. Saturnismo causado por projetil de arma de fogo no quadril: relato de dois casos [Saturnism caused by lead poisoning in the hip region: report of two cases]. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Univ São Paulo 1994; 49: 124–127.

Meyer PA, Brown MJ, Falk H . Global approach to reducing lead exposure and poisoning. Mutat Res 2008; 659: 166–175.

Onalaja AO, Claudio L . Genetic susceptibility to lead poisoning. Environ Health Perspect 2000; 108 (Suppl 1): 23–28.

Boeckx RL . Lead poisoning in children. Anal Chem 1986; 58: 274A–288A.

Begovic V, Nozic D, Kupresanin S, Tarabar D . Extreme gastric dilation caused by chronic lead poisoning: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 2599–2601.

Gracia RC, Snodgrass WR . Lead toxicity and chelation therapy. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2007; 64: 45–53.

Vaccaro AR, Silber JS . Post-traumatic spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001; 26 (24 Suppl): S111–S118.

Arnold PM, Baek PN, Stillerman CB, Rice SG, Mueller WM . Surgical management of lumbar neuropathic spinal arthropathy (Charcot joint) after traumatic thoracic paraplegia: report of two cases. J Spinal Disord 1995; 8: 357–362.

Brown CW, Jones B, Donaldson DH, Akmakjian J, Brugman JL . Neuropathic (Charcot) arthropathy of the spine after traumatic spinal paraplegia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992; 17 (6 Suppl): S103–S108.

Cağavi F, Kalayci M, Seçkiner I, Cağavi Z, Gül S, Atasoy HT et al. Migration of a bullet in the spinal canal. J Clin Neurosci 2007; 14: 74–76.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

de Barros Filho, T., Cristante, A., Marcon, R. et al. Gunshot injuries in the spine. Spinal Cord 52, 504–510 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.56

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.56