Abstract

Study design:

Cross-sectional survey.

Objectives:

To examine factors that may enhance and promote resilience in adults with spina bifida.

Setting:

Community-based disability organisations within Australia.

Methods:

Ninety-seven adults with a diagnosis of spina bifida (SB) completed a survey comprising of demographic questions in addition to standardised self-report measures of physical functioning (Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique), resilience (Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, 10 item), self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale), self-compassion (Self-compassion Scale) and psychological distress (Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 21 item).

Results:

The majority (66%) of respondents reported moderate to high resilience. Physical disability impacted on coping, with greater CD-RISC 10 scores reported by individuals who were functionally independent in addition to those who experienced less medical co-morbidities. Significant correlations between resilience and psychological traits (self-esteem r=0.36, P<0.01; self-compassion r=0.40, P<0.01) were also noted. However, the combined contribution of these variables only accounted for 23% of the total variance in resilience scores (R2=0.227, F(5,94)=5.23, P<0.01).

Conclusion:

These findings extend current understanding of the concept of resilience in adults with a congenital physical disability. The suggestion is that resilience involves a complex interplay between physical determinants of health and psychological characteristics, such as self-esteem and self-compassion. It follows that cognitive behavioural strategies with a focus on self-management may, in part, contribute to the process of resilience in this group. Further large-scale and longitudinal research will help to confirm these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resilience, the process of positive adjustment in the context of significant life adversity, is an important element of positive mental health following physical disability.1 It involves a dynamic interplay between protective factors that buffer the adverse effects of a challenging situation, and risk factors that are associated with a higher likelihood of maladaptive outcomes.2 However, resilience has been relatively under-researched among individuals with a congenital condition. Consequently, although resilient trajectories defined by low levels of psychological distress have been identified by up to 56% of individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury,3 it is unclear whether a similar prevalence is reported among adults with spina bifida (SB). Indeed, it is argued that the adjustment process for SB, which is affected by childhood social experiences, is psychologically distinct from that of acquired physical disability.4

Research examining the characteristics of resilience in disability groups has also been theoretically limited by its primary focus on biomedical risk factors, including medical comorbidities and degree of functional independence.1 This is in contrast to a strength-based approach to mental health care, which involves assessing the psychological assets or characteristics and beliefs that enhance adaptive coping.5 The strength-based approach is particularly advantageous when working with individuals with chronic SB, as the focus is on helping individuals identify and build from their existing capacities as they continually adjust and re-adjust to their disability and its associated physical and psychosocial challenges.1 A greater awareness of resilience-promoting factors also has important implications in developing psychological interventions for this group, including an ability to focus on assessment and intervention techniques that enhance positive adjustment outcomes.5

A psychological factor that may enhance the resilience process is self-esteem, or one’s sense of self worth and value. Self-esteem has been identified as an important coping trait among adolescent samples with SB.6, 7 However, recent evidence with non-clinical samples suggests that self-esteem can also be dysfunctional, with grandiose or inaccurate self-concept resulting in poor psychological outcomes, including social isolation.8 Furthermore, self-esteem is often contingent on successful attainment and can therefore fluctuate, depending on one’s successes or failures.8

In comparison, self-compassion, which involves being caring and compassionate to oneself when faced with hardship or adversity, is considered to be a more stable characteristic.9 Self-compassion has been found to moderate reactions to distressing situations, with self-compassionate individuals being less likely to ruminate about unpleasant self-evaluations.10 Research indicates that self-compassion is significantly related to resilient behaviours and skills in the general population including happiness, positive self-evaluations and greater feelings of social connectedness.11 Notably, the association between self-compassion, resilience and mental health has largely been examined in relation to commonly encountered hardships, such as receiving negative interpersonal feedback or reflecting on negative personal experiences.10 Hence, while there are sound theoretical reasons to believe that self-compassion promotes resilience, it is not known whether this construct is relevant to disparate populations, such as individuals with SB.

These findings suggest that further research examining the contribution of psychological traits and resources, such as self-esteem and self-compassion, to resilient coping among individuals with an acquired physical disability is needed. The main objective of this study was to therefore investigate the characteristics of resilience in a community sample with SB, including the impact of disability severity on resilience levels and the association between resilient skills and behaviours and psychological functioning. Given the limited research in the area of resilience and SB, the magnitude of these relationships could not be predicted.

Materials and methods

Measures

Demographic and medical information

This comprised of age, gender, current employment and relationship status, medical co-morbidities experienced (for example, pain) and the Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique, Physical Independence Subscale (CHART).12 CHART scores can range from 0 to 100 with higher numbers indicating greater ability to sustain an independent lifestyle.12 The CHART has demonstrated good internal consistency.12

Connor Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 10)

Responses are on a five-point Likert scale—with higher scores indicating greater capacity to change and cope with adversity.13 The CD-RISC 10 demonstrates good internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent and divergent validity.13

Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSES)

Item scores are totalled (with four items reverse scored), so that higher scores indicate higher trait self-esteem.14 Alpha reliabilities have ranged from 0.88 to 0.90.14

Self-compassion Scale (SCS)

Items are rated on a five-point scale, with higher scores representing trait-level perseverance and passion for long-term goals.9 The SCS has demonstrated good internal consistency reliability (alpha=0.92) and test–retest reliability (r=0.93).9

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales—21 item (DASS-21)

Items are scored on a four-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater symptomatology of depression, anxiety and/or stress.15 The DASS-21 exhibits high reliability and convergent validity.15

Procedures

Members of two disability support organisations within South Australia, the Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus Association (N=350) and Disability SA (N=154), were initially approached to participate in a mail survey. This achieved a low (n=47; 11%) response rate, despite the offer of a small monetary incentive for participation. To improve recruitment, an online survey, hosted through SurveyMonkey, was subsequently developed and emailed to social networking sites (that is, Facebook and Twitter) of SB support groups throughout Australia. Eligible participants were adults with a confirmed diagnosis of SB (that is, occulta, meningocele, myelomeningocele or myeloschisis, with and without associated hydrocephalus).16

Data analysis

Group differences in psychological functioning between respondents with ‘high’ versus ‘low’ resilience scores (based on the samples’ average CD-RISC 10 score13) were initially examined. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was then used to determine the association between all outcome measures (that is, medical co-morbidities, CHART, CD-RISC 10, RSES, SCS and DASS-21). Finally, a standard multiple regression was run to examine the individual contribution of each variable to resilience (CD-RISC 10). The Enter method was adopted, whereby all independent variables were entered into the equation simultaneously. This method was considered appropriate because no theoretical predictions had been made concerning the importance of the variables in relation to resilience. A sample size of 64 was the minimum required to detect statistically significant results (P<0.05) with power set at 0.80 for this regression model.17 Statistics were calculated using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS; Version 20.0.0.1, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Statement of ethics

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Adelaide (protocol H-2012-163). Accordingly, all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Results

Sample characteristics

The final sample (N=97) primarily comprised of females (66%, n=64; Table 1), with 56% (n=54) being employed (for example, part-time or full-time) or actively engaged in community activities (for example, volunteering). The majority described experiencing multiple medical issues secondary to their SB, including chronic pain and pressure ulcers, with associated surgical interventions (mean number of surgeries in lifetime: 17; s.d.=19). A significant minority (22%) also identified experiencing social isolation and bullying as a consequence of their disability. Despite these co-morbidities, relatively high CHART scores were reported (M=87.59, s.d.=24.01), although the large s.d. suggests considerable variation in the degree of physical independence experienced by this sample (Table 1).

Characteristics of resilience

Sixty-six percent (n=64) of the sample reported moderate-to-high scores on the CD-RISC 10 (that is, score 20–35;13 Table 2), suggesting that resilient qualities and behaviours were present to some degree. Respondents also reported moderate levels of self-esteem (that is, RSES score 15–25,14 62.9%, n=61) and self-compassion (that is, SCS score 15–25,9 77.3%, n=77).

On average, sub-clinical levels of depression (55.7%, n=54, score <10), anxiety (55.7%, n=54, score <8) and stress symptomatology (60.8%, n=59, score <15), based on the DASS-21 definitions of symptom severity,15 were noted (Table 2). Nonetheless, a significant minority could be classified as clinical ‘cases’ having reported severe–to-extremely severe levels of depression (21.6%, n=21, score ⩾21), anxiety (22.7%, n=22, score ⩾15) and/or stress (15.5%, n=15, score ⩾26).15

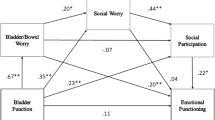

Relationships between resilience and physical and psychological functioning

Significant, albeit small, negative correlations were noted between the number of medical co-morbidities experienced by this sample and most of the psychological variables, aside from resilience (Table 3). In addition, low CHART scores were related to higher levels of anxiety and stress (Table 3). This suggests that cumulative medical stressors experienced by this group, in addition to physical disability, had a negative impact on psychological functioning.

In relation to the psychological characteristics of resilience, independent samples’ t-tests revealed statistically significant group differences in self-esteem (t(93)=−3.00, P<0.01, d=0.61) and self-compassion (t(94)=−3.25, P<0.01, d=0.66) between low and high resilience scores, both associated with positive and moderate effect sizes. This finding was further supported by the significant positive correlations between resilience and self-esteem and self-compassion (Table 3). In contrast, resilience correlated negatively with depression, anxiety and stress, suggesting that symptoms of psychological distress may impede the development of skills and behaviours that contribute to resilient coping. Moreover, psychological distress (DASS-21) was associated with lower levels of self-esteem and self-compassion (Table 3).

Predictors of resilience

Multicollinearity statistics revealed high inter-correlations between the DASS-21 subscales (that is, r>0.64); these subscales were therefore summed to produce a composite measure of total distress.15 Five independent variables were entered into the regression equation: medical co-morbidities, physical disability, self-esteem, self-compassion and psychological distress. The total variance explained by the model as a whole was 23% (R2=0.227, F(5,94)=5.23, P<0.01; Table 4). Psychological distress made the only unique and significant contribution (β=−0.26, P<0.05), with the direction indicating that general psychological well-being contributes to greater resilience.

Discussion

The current survey examined resilience levels in adults with congenital SB. Moderate levels of resilient coping were identified, with both medical and psychological variables contributing to the resilience process to varying degrees. The suggestion is that despite the challenges faced by individuals with SB, the majority report successful emotional adjustment.

This finding is consistent with previous research in which resilience consistently emerges as the most common response to adversity among physical disability groups, as demonstrated by stable, healthy levels of psychological and physical functioning, as well as the capacity for positive emotions and generative experiences.1, 18 Of note, however, is that the mean resilience score in this study was lower (M=25.7, s.d.=8.1) than the CD-RISC 10 scores reported by individuals with an acquired spinal cord injury in a comparative cross-sectional study (M=29.5, s.d.=7.2).3 It is possible, then, that the complex and demanding nature of SB, including difficult childhood experiences and long-term medical management, may impede or limit positive adaptation.

Although degree of physical disability was not significantly associated with resilience, it did contribute to affect (that is, anxiety and stress) among this sample. Moreover, experiencing secondary medical complications, such as chronic pain and pressure sores, negatively impacted on self-esteem and self-compassion. This is consistent with previous research, in that disability severity can cause frustration and distress.6

The findings that self-esteem and self-compassion correlate with resilience, whereas psychological distress impedes this process, are also consistent with previous research that demonstrates strong associations between these positive psychological variables and life satisfaction.8, 9, 11 More specifically, having a salient source of positive self-regard and an ability to be kind to oneself is likely to promote positive adaptation when faced with adversity. Another interesting finding was the strong correlation between self-esteem and self-compassion, suggesting that the two constructs are not psychologically distinct.8 It may be that the two constructs function simultaneously to promote positive adaptation. For example, self-compassion may reduce degree of self-criticism and subsequent depressive symptoms, while self-esteem may bolster perceived ability to cope with the demands of SB, resulting in more proactive coping.

However, the combined contribution of the physical and psychological variables to resilience was modest, suggesting that other untested variables may better explain resilient coping for this sample.2 This may include social networks. In this sample, all participants had access to targeted health resources and support services via their respective SB association. Most (54%) were also in supportive personal relationships and engaged in their community, through paid or unpaid employment. In combination these resources may help to buffer the physical and emotional impact of their disability.6

The current findings have important implications for clinicians working with this population. Clinicians should assess psychological constructs such as self-esteem and self-compassion, and target interventions to promote these protective processes and thereby reduce the risk of developing symptoms of distress, including depression.1, 5 This might include therapies with a cognitive behavioural focus such as acceptance and commitment therapy, which can help to protect and enhance resilient skills and behaviour.5 However, the application of these therapies to SB groups requires further investigation. Self-management programs that target self-efficacy in relation to disability-specific tasks3 may also promote resilience by reducing potential medical stressors faced by this group, including increased physical dependence due to secondary complications, such as chronic pain.

These findings need to be considered in the context of the study limitations. First, the sample primarily comprised of females (n=64, 66%). Although this bias is consistent with prevalence rates for SB in western countries,19 research has also shown females to report significantly less self-compassion than males.9 It is also possible that individuals with higher degrees of resilience were more likely to participate, particularly given that the sample primarily comprised of participants with access to an online SB support network. Future research should therefore use a more diverse sample to allow broader generalisations to be made.

Second, it can be argued that a complex construct such as resilience cannot be measured with a uni-dimensional measure such as the CD-RISC 10. Resilience involves negotiating risk situations with protective resources at a psychological, family and community level.2 At present, however, there is no one measure of resilience that best captures this complex interaction. Even the extended CD-RISC, which incorporates broad constructs including affect, personal experience, spirituality and stress tolerance, has been criticised for not specifying the particular skills an individual should possess, or lack, to achieve resilience.20

The final limitation is the reliance on self-reported questionnaires, which may include self-presentation and social desirability biases. However, given the wide sample base used in this study, this was considered to be the most efficient means of testing the proposed aims. The method for data collection may have also created a sample bias, whereby individuals with greater functional disability and/or those without internet access were unable to respond to the survey. Provision of telephone or face-to-face surveys would help bolster recruitment rates by targeting individuals who otherwise would not be able to participate.

Despite these limitations, the present study contributes to our understanding of the resilience process in adults with SB. The suggestion is that resilience is a common outcome that can be achieved by a variety of different pathways, including treatments to enhance positive psychological constructs and/or reduce psychological distress. Further research examining the potential social and environmental factors that may foster resilience, including the amount and type of social support, will help to extend on these findings.

Data Archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Craig A . Resilience in people with physical disabilities. In: Kennedy P, (ed.). Oxford Handbook of Rehabilitation Psychology. Oxford University Press: Oxford, pp 474–491 2012.

Kumpfer KL . Factors and processes contributing to resilience: the resilience framework. In: Glantz MD, Johnson JL, (eds).. Resilience and Development: Positive Life Adaptions. Kluwer Academic Publishers: New York, pp 179–224 2002.

Kilic S, Dorstyn D, Guiver N . Examining factors that contribute to the process of resilience following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 1–5.

Huebner RA, Thomas KR . The relationship between attachment, psychopathology, and childhood disability. Rehabil Psychol 1995; 40: 111–124.

Padesky CA, Mooney KA . Strengths-based cognitive–behavioural therapy: a four-step model to build resilience. Clin Psychol Psychother 2012; 19: 283–290.

Barf HA, Verhoef M, Jennekens-Schinkel A, Gooskens RHJM, Prevo AJH . Life satisfaction of young adults with spina bifida. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007; 49: 458–463.

Bellin MH, Sawin KJ, Rouz G, Buran CF, Brei TJ . The experience of adolescent women living with spina bifida part 1: self-concept and family relationships. Rehabil Nurs 2007; 32: 57–67.

Neff ND . Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 2011; 5: 1–12.

Neff KD . The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity 2003; 2: 223–250.

Leary MR, Tate EB, Adams CE, Batts AA, Hancock J . Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self relevant events: the implications of treating oneself kindly. J Pers Soc Psychol 2007; 92: 887–904.

Neff KD, Kirkpatrick KL, Rude SS . Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. J Res Pers 2007; 41: 139–154.

Whiteneck GG, Charlifue SW, Gerhart KA, Overholser JD, Richardson GN . Quantifying handicap: a new measure of long-term rehabilitation outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992; 73: 519–526.

Connor KM, Davidson JRT . Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 2003; 18: 76–83.

Rosenberg M . Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ. 1965.

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF . Manual for the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales 2nd edn. Psychology Foundation: Sydney. 1995.

Fletcher JK, Brei TJ . Spina bifida: a multidisciplinary perspective. Dev Disabil Res Rev 2010; 16: 1–5.

Cohen J . A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992; 112: 155–159.

Bonanno GM . Loss trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol 2004; 59: 20–28.

Shin M, Besser LM, Siffel C, Kucik JE, Shaw GM, Lu Chengxing L et al. Prevalence of spina bifida among children and adolescents in 10 regions in the United States. Pediatrics 2010; 126: 274–279.

White B, Driver S, Warren A-M . Considering resilience in the rehabilitation of people with traumatic disabilities. Rehabil Psychol 2008; 53: 9–17.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful for the cooperation of the many organisations that participated in this research, in particular the Spina Bifida Association of South Australia and Disability SA who dedicated their time and staffing resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hayter, M., Dorstyn, D. Resilience, self-esteem and self-compassion in adults with spina bifida. Spinal Cord 52, 167–171 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.152

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.152

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Self-compassion, Resilience, Fear of COVID-19, Psychological Distress, and Psychological Well-being among Turkish Adults

Current Psychology (2023)

-

Self-Compassion Scale for Youth: Turkish Adaptation and Exploration of the Relationship with Resilience, Depression, and Well-being

Child Indicators Research (2022)

-

Positive Psychology for Mental Wellbeing of UK Therapeutic Students: Relationships with Engagement, Motivation, Resilience and Self-Compassion

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2022)

-

Positive Psychology of Malaysian University Students: Impacts of Engagement, Motivation, Self-Compassion, and Well-being on Mental Health

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2021)

-

Mindfulness-Related Variables and Sexual/Relationship Satisfaction in People with Physical Disabilities

Mindfulness (2020)