Abstract

Study design:

Case report.

Objective:

Vertebral osteomyelitis, usually presented with back pain and local tenderness, can pose a great challenge of early diagnosis among spinal cord injury (SCI) patients who lost sensation below the injured level. We reported a paraplegic patient who had recurrent febrile episodes after being treated as urinary tract infection initially and was discovered later to have vertebral osteomyelitis.

Case report:

A 41-year-old man, completely paralyzed at the T11 level and with Foley catheterization for 9 years, was re-admitted within 2 weeks for recurrent fever, turbid urine, bacteriuria and bacteremia with Escherichia coli. Spine X-ray and renal, cardiac and abdominal ultrasonography showed no definite lesions related to infection in a previous admission. Intermittently febrile episodes continued despite treatment with antibiotics for 1 week. He had no pressure sores or other wounds. Computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging showed lumbosacral osteomyelitis and bilateral paravertebral abscess. The patient underwent debridement of paravertebral tissue. Fever subsided soon after surgery and the patient continued antibiotics and remained free of fever at a 1-year follow-up.

Conclusion:

It can be challenging to diagnose vertebral osteomyelitis below injury levels in SCI patients. Vertebral osteomyelitis should be considered in febrile SCI patients even with known infectious foci, as classic symptoms of osteomyelitis are lacking in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In comparison with the general population, spinal cord injury (SCI) patients had a higher incidence of vertebral osteomyelitis.1 Nevertheless, classic symptoms of vertebral osteomyelitis, such as back pain, neurological deficits and vertebral body tenderness,2 are mostly absent in SCI and it challenges the early diagnosis.

We presented an SCI patient with recurrent fever and bacteriuria with Escherichia coli. After unsatisfactory treatment by parental antibiotics, he was proved to have a vertebral osteomyelitis and paraspinal abscess below the injury level. It highlights the importance of thorough investigation of occult infection in febrile SCI patients when the treatment of the primary infection foci was not successful.

Case report

A 41-year-old man, denying major systematic disease except being completely paralyzed at T11 level and with Foley catheterization for 9 years, had been hospitalized previously for fever, turbid urine, bacteriuria and bacteremia with E. coli. During his first admission, he had been treated with ciprofloxacin 400 mg q12h and then cefuroxime 1.5 g q12h for 7 days. Spine X-ray (Figure 1a), renal, cardiac and abdominal ultrasonography failed to identify other infection foci. He was therefore discharged with no fever, no leukocytosis, but elevated C-reactive protein (CRP; Table 1).

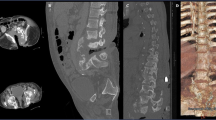

Plain X-ray (a) taken at first admission and contrasted computerized tomography (b) and T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (c) of lumbosacral spine taken at second admission. The X-ray showed previous spinal fracture with instruments, but no apparently bony destruction or soft tissue swelling. At 4 weeks later, computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed extensive destruction of bone at L5/S1 level (arrows) and abscess of psoas muscles and epidural space with ring enhancement (arrow head).

At 2 weeks after his first discharge, he was admitted for recurrent symptoms. He denied a history of recent weight loss, but reported fatigue during febrile episodes. On admission, physical examinations showed no pressure sore or any erythema, pain, swelling or vertebral body tenderness at back but there was leukocytosis and elevated CRP (Table 1). Urine culture on admission yielded E. coli, sensitive to second generation of cephalosporin. He was soon prescribed intravenous cefuroxime (1.5 g q12h) for 1 week, but low-grade fever persisted at night. Therefore, pelvic computerized tomography was arranged at 1 week after second admission to look for other infectious foci. Incidentally, osteomyelitis and a paraspinal abscess at L4–S1 was found (Figure 1b), and magnetic resonance imaging confirmed L5/S1 spondylodiscitis and bilateral paraspinal, psoas muscles and epidural abscesses (Figure 1c). Therefore, computerized tomography guide biopsy was performed at 2 weeks after admission, but the Gram stain, acid-fast stain, bacterial and tuberculosis culture were all negative for any microorganism.

After 6 weeks treatment with ceftriaxone (2 g q12h), his CRP was still elevated (6.8 mg dl−1) and magnetic resonance imaging showed residual infectious spondylodiscitis at L5–S1 and a persistent abscess. The patient then underwent discectomy and debridement of paravertebral tissue at 8 weeks after second admission. The culture for aerobic bacterial and tuberculosis of surgical specimen grew no pathogen. Fever subsided within 1 week of surgery, and CRP decreased to 0.76 mg dl−1 (Table 1). He received another 2 weeks treatment with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g q12h) and 2 weeks treatment with oral ceftibuten (400 mg q.d.) and remained afebrile at 1 year.

Discussion

Paraplegic patients are at high risk of vertebral osteomyelitis, especially in the completely paralyzed group.1 Vertebral osteomyelitis often presented with back pain, fever, tenderness at the vertebral body and sometimes neurological symptoms related to spinal cord compression.2 The above symptoms, except for fever, are mostly absent in the paraplegics. Severe vertebral osteomyelitis in SCI had been reported, and unsatisfactory response to antibiotic treatment might be the only clue for diagnosis for those without draining sinuses or fluctuant masses,3 as in the reported case.

Vertebral osteomyelitis can occur from hematogenous inoculation, most often from the urinary tract,2 which was a likely etiology for the current case. The lumbar X-ray taken in the first admission did not report bony lesions, but it did not rule out early osteomyelitis retrospectively. The average time from the initial presentation to diagnosis ranges from a few weeks to 6 months.4 Moreover, abnormalities on plain radiographs generally occur several weeks after the onset of the infection.2 We suspected the osteomyelitis had developed at the first admission, and the second admission could be related to the relapse after incomplete treatment.

The diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis required a high index of clinical suspicion, prompt image evaluation and a tissue proof. In our case, persistently elevated CRP despite antibiotic treatment aroused the clinical suspicion of undetected infection. Antibiotics according to culture results should be administered for minimally 4–6 weeks, preferably by intravenous route. Without early detection and treatment, vertebral osteomyelitis can result in severe bone destruction, paraspinal abscess, epidural abscess and even mortality.2

Conclusion

The case report highlighted the difficulty in diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis in SCI patients. Vertebral osteomyelitis should be considered in febrile SCI patients, particularly if the primary infection focus has been treated but with incomplete response. Culture should be attained, with prompt antibiotic treatment and surgical intervention, if indicated, to prevent severe morbidity and mortality.

References

Frisbie JH, Gore RL, Strymish JM, Garshick E . Vertebral osteomyelitis in paraplegia: incidence, risk factors, clinical picture. J Spinal Cord Med 2000; 23: 15–22.

Mylona E, Samarkos M, Kakalou E, Fanourgiakis P, Skoutelis A . Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: a systematic review of clinical characteristics. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2009; 39: 10–17.

Malik GM, Sapico FL, Montgomerie JZ . Severe vertebral osteomyelitis in patients with spinal cord injury. Arch Intern Med 1982; 142: 807–808.

Kern RZ, Houpt JB . Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: diagnosis and management. Can Med Assoc J 1984; 130: 1025–1028.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hsiao, MY., Liang, HW. Delayed diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis in a paraplegic patient. Spinal Cord 49, 1020–1022 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.39

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.39

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Beyond broken spines–what the radiologist needs to know about late complications of spinal cord injury

Insights into Imaging (2015)