Abstract

Conspiracy theories are part of mainstream public life, with the potential to undermine governments, promote racism, ignite extremism and threaten public health efforts. Psychological research on conspiracy theories is booming, with more than half of the academic articles on the topic published since 2019. In this Review, we synthesize the literature with an eye to understanding the psychological factors that shape willingness to believe conspiracy theories. We begin at the individual level, examining the cognitive, clinical, motivational, personality and developmental factors that predispose people to believe conspiracy theories. Drawing on insights from social and evolutionary psychology, we then review research examining conspiracy theories as an intergroup phenomenon that reflects and reinforces societal fault lines. Finally, we examine how conspiracy theories are shaped by the economic, political, cultural and socio-historical contexts at the national level. This multilevel approach offers a deep and broad insight into conspiracist thinking that increases understanding of the problem and offers potential solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In laying out a case for revolution, the authors of the US Declaration of Independence relied heavily on a conspiracy theory1: policies such as taxes on tea were not, as Parliament claimed, merely a way of having colonies pay their fair share for the costs of keeping them in the British Empire. Rather, they were part of a hidden agenda to exert an oppressive dictatorship over what later became the United States of America. The Declaration of Independence example illustrates that conspiracy theories do not just reside in the mind or heart of individuals. Frequently, they are positioned within intergroup contests, and are shaped also by sociopolitical, economic and cultural factors. Examples like this are also a reminder that conspiracy theories are not new phenomena. Although it is common wisdom that society is increasingly prone to conspiracy theories — or that society is entering a golden age of conspiracy theories — historical analyses find no support for this notion2,3. Rather, there has been a steady drumbeat of conspiracy theories for centuries, and some have argued that the propensity to engage with them has an evolutionary basis4.

Although belief in conspiracy theories is not a new phenomenon, what is relatively new is to treat conspiracy theories as an issue worthy of psychological inquiry. More than half of academic publications on conspiracy theories in psychology have been published since 2019. The growth in research interest is partly grounded in the position that conspiracy theories can have serious, negative effects that need to be managed. For example, conspiracy beliefs are implicated in a number of anti-science attitudes, which slow society’s ability to respond to challenges associated with climate change5,6,7,8,9 and public health crises10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Conspiracy theories also trigger political aggression: they are used as tools to derogate political opponents17, encourage political violence18,19, promote prejudice18,20,21 and recruit terrorists22. More generally, conspiracy beliefs help to accelerate and consolidate mistrust of — and anxiety about — established institutions, including government23,24. Although a degree of healthy skepticism about official accounts of events should be encouraged, chronic skepticism becomes a problem as people ignore established facts and resist solutions to societal problems. As such, the ‘conspiracy theorist’ has become emblematic of what some have called the anti-enlightenment movement25 and others have called the post-truth society26.

In this Review, we provide a narrative synthesis of the literature on belief in conspiracy theories organized by level of analysis (Fig. 1). First, we describe the individual-level factors that might predispose individuals to believe conspiracy theories (micro level of analysis). Next, we review research examining conspiracy theories as an intergroup phenomenon (meso level of analysis), which recognizes that conspiracy theories are reinforced and negotiated among collectives, reflecting and creating societal fault lines. We then examine how belief in conspiracy theories is shaped by economic, political, cultural and socio-historical contexts (macro level of analysis). We conclude by considering how insights at these different levels can be integrated, and offer suggestions for future research.

Before beginning, some definitional housekeeping is required. There is debate in both the psychological and philosophical literature about what beliefs warrant the label ‘conspiracy theory’27,28,29. Here we rely on the definitions typically used in the psychological literature, according to which a conspiracy theory is an explanation for important events and circumstances that involve secret plots by groups with malevolent agendas30. For the sake of conciseness, we use the term ‘conspiracy belief’ to refer to both belief in specific conspiracy theories and the more general worldview that conspiracies are common. We also note that conspiracy theories are conceptually distinct from the broader term ‘misinformation’. For example, the belief that 5G causes COVID-19 is not a conspiracy theory. But the belief that telecommunication companies know that 5G causes COVID-19 and have suppressed the evidence, or that the installation of 5G technology is part of a broader plot to depopulate the Earth, are conspiracy theories.

Finally, in line with most academic accounts, we use the term ‘conspiracy theory’ in a way that is agnostic about whether the theory is true. The notion of what constitutes evidence for a theory is subjective, so it would be unsustainable as a definitional practice to draw clear lines separating plausible from implausible conspiracy theories. However, such distinctions are frequently invoked in the literature; indeed, researchers often wish to investigate conspiracy theories precisely because they can be fanciful and so discrepant from consensual accounts of reality that they cause problems. We therefore write this Review sympathetic to the notion that the motives of powerful elites should be interrogated, and fully aware that conspiracy theories might one day be proved to be true, but also guided by the principle that not all subjective truths are equally valid proxies for reality.

Individual-level factors

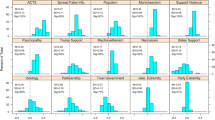

The vast majority of psychological literature on conspiracy belief has focused on factors that predispose individuals to endorse conspiracy theories. There are five broad subdomains of investigation: cognitive, clinical, motivational, personality and developmental. Figure 2 presents a summary of meta-analytic evidence for relationships between conspiracy belief and individual-level variables from each of these domains, where available. Owing to the sheer quantity of studies on individual-level factors, it is not possible to provide an exhaustive review of all relevant variables. We have attempted to cast the nomological net wide, but we were particularly likely to include variables if the field as a whole deemed it to be important (as evidenced by a large number of studies using that variable) and/or we judged that the variable is illuminating or generative in terms of understanding the psychology of conspiracy theories. We note that we do not cover research on demographic differences in conspiracy belief because many of these differences are potentially better explained by the psychological variables that underpin them (for example, the effects of education might be explained by other variables such as powerlessness).

Estimated effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals for the correlations between individual-level and intergroup factors and conspiracy beliefs as reported by five meta-analyses. Marker size and line thickness represent the number of primary studies included in the meta-analysis: larger markers and thicker lines denote 30 primary studies; smaller markers and thinner lines denote 20 primary studies. CI, confidence interval. Data taken from refs.46,59,81,102,135.

The cognitive approach

The cognitive perspective focuses on the logical fallacies displayed by those who believe conspiracy theories. Examples of logical fallacies include confirmation biases (focusing only on evidence that confirms the theory and disregarding inconsistent evidence)31, identification of illusory patterns in random events32,33, flawed heuristics such as ‘nothing happens by accident’ or ‘big events must have big causes’34,35, and willingness to hold conspiracy beliefs that appear to be mutually incompatible (for example, simultaneously believing that Princess Diana is still alive and that she was murdered)36. This body of research implies that conspiracy beliefs are based on faulty logic rooted in styles of thinking.

One well-established pattern is that conspiracy belief is associated with relatively low levels of analytical thinking and high levels of intuitive thinking. In other words, people who self-report as preferring slow, deliberative, emotionally neutral thinking are less likely to believe conspiracy theories. People who prefer fast, heuristic thinking — grounded in gut feeling and emotion — are more likely to believe conspiracy theories. This relationship has been reported consistently across multiple contexts and measures37,38,39,40,41,42,43 and has also been demonstrated experimentally: compared with control conditions, conspiracy beliefs were reduced when participants were given tasks that elicited analytical thinking38 and critical thinking44.

Although analytical thinking is highly correlated with general cognitive ability (for example, numerical and verbal skill), the two constructs are conceptually separable. Interestingly, when both are measured simultaneously there is evidence that cognitive ability is a somewhat more robust (negative) predictor of conspiracy belief than analytical thinking45. This suggests that cognitive ability might be a protective factor in terms of believing conspiracy theories, perhaps because it helps people make realistic judgements in the face of high quantities of information. Meta-analysis indicates a modest but reliable tendency for people to have stronger conspiracy beliefs when they have lower cognitive ability46 (Fig. 2). It is notable that this is the only cognitive construct represented in published meta-analyses to date. As the quantity of studies grow, future meta-analyses can lend greater nuance to the question of how cognitive style is associated with conspiracy beliefs.

An example of this nuanced approach is research examining whether conspiracy belief is linked to a biased tendency to attribute intent. Conspiracy beliefs have been associated with anthropomorphism47,48, assumptions that inanimate objects are animate49, and willingness to attribute purpose and consciousness to the movements of geometrical shapes48. These variables might reflect a hyper-sensitivity to detecting agency and intent, which could in turn could lead to an intuitive worldview that someone is ‘pulling strings’ behind random events.

Another line of research has examined whether those who believe conspiracy theories display a dispositional propensity to misunderstand the nature of randomness. Data on this issue are mixed. On one hand, conspiracy belief is unrelated to people’s ability to judge the randomness of binary strings of Os and Xs50. On the other hand, studies have found correlational51,52 and experimental53 relationships between conspiracy beliefs and a bias towards overestimating the likelihood of co-occurring or spatially adjacent events, and drawing causal links between them, such as the co-occurrence of COVID-19 cases with 5G infrastructure (the conjunction fallacy). This suggests that those who believe in conspiracy theories have a tendency to base judgements on subjective perceptions of coincidences rather than objective assessment of probabilities.

Finally, a small body of research has examined the tendency to reach conclusions impulsively and based on limited information. This jumping-to-conclusions bias is typically measured through variants of the bead task: participants are shown two containers holding two types of bead in reversed ratios (for example, one contains 60% orange beads; the other 40% blue beads). Beads are then ‘drawn out’ one by one and participants declare which container they come from once they feel ready to decide. People who are more likely to believe conspiracy theories tend to make their decision earlier54. This bias is also a reliable measure of psychosis-proneness55, consistent with links between psychosis and conspiracy belief, as discussed in the next section.

The clinical approach

The cognitive approach focuses on how everyday thinking styles and biases predispose people to believe conspiracy theories. Scholars taking a clinical approach have taken this notion a step further, documenting how conspiracy beliefs can reflect more pervasive disorders of thought. For example, there are links between conspiracy beliefs and almost all personality disorders (which are characterized by disruptive patterns of thinking)56. Furthermore, paranoid delusions — associated with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and some forms of dementia — frequently incorporate conspiracy beliefs.

Schizotypy (a continuum of characteristics ranging from ‘normal’ levels of unusual thinking to psychosis) is the most frequently examined clinical construct, probably because it can be meaningfully measured in both clinical and subclinical populations. Several studies have found that people who are higher in conspiracy beliefs also score higher on self-report measures of schizotypy37,57,58. A meta-analytic synthesis of this research found a medium-sized correlation overall46 (Fig. 2).

Some researchers have suggested that paranoid ideation (thinking that is dominated by suspicious or persecutory content, and a symptom of several clinical disorders) might link clinical issues to conspiracy beliefs. Indeed, at least twenty studies have documented a relationship between paranoid ideation and conspiracy beliefs59,60 and meta-analyses demonstrate a medium-sized relationship46 (Fig. 2). However, there are important empirical and conceptual differences between conspiracy beliefs and paranoid ideation59,61. Whereas paranoia implicates a broad range of sinister actors, conspiracy beliefs tend to specifically implicate powerful elites. Furthermore, people experiencing paranoid ideation tend to see the self as a target of persecution, whereas those who believe conspiracy theories tend to see society more generally as the target. Overall, the research indicates that there might be a pathological underpinning to some conspiracy beliefs, but there is no evidence that conspiracy beliefs are reducible to paranoia.

A second stream of clinical literature examined relationships between conspiracy beliefs and affective states. People who are predisposed to believe conspiracy theories tend to feel high levels of self-related threat62,63 and are more prone than the rest of the population to report emotional distress such as anxiety and depression64,65,66. However, the causal relationship between conspiracy beliefs and emotional distress is unclear. One possibility is that belief in conspiracy theories is a consequence of distress. For example, a conspiracy theory could be a palliative response to rejection67, a consequence of avoidance coping68, or a projection of feelings of threat onto an outgroup64. Another possibility is that conspiracy theories are a cause of distress; that the notion of elites conducting malevolent hoaxes on the public is inherently depressing and anxiety-provoking. Of course, both causal directions could be true. Indeed, longitudinal research suggests that negative feelings and conspiracy beliefs mutually reinforce each other, creating negative feedback loops of anxiety and mistrust69.

The motivational approach

A broader line of reasoning (mostly in the social psychology literature) proposes that conspiracy theories are motivated beliefs endorsed in an attempt to satisfy unmet psychological needs and desires30. For example, in one study participants that were asked to recall a threatening experience in which they did not have control endorsed conspiracy theories more than those asked to recall a threatening experience in which they did have control70. This result was interpreted to reflect a broader phenomenon, whereby thwarted control motivates people to see illusory patterns in random events as a way of introducing order and predictability to life70,71,72. Subsequent correlational research confirmed the relationship between control and conspiracy beliefs73,74.

However, not all literature is sympathetic to the control argument. Some studies highlight a paradox: although people display stronger conspiracy belief when denied control, exposure to conspiracy theories typically reduces people’s sense of control and autonomy6,12,75. In addition, there has been mixed success in replicating the experimental effects of control; some studies have shown similar effects to those reported above76,77 but others have reported null effects73,78,79 and one even reported the reverse effect80. Overall, a meta-analysis revealed a non-significant relationship between control and conspiracy beliefs81 (Fig. 2). The mixed experimental evidence calls into question the notion that lack of control has a causal effect on conspiracy beliefs.

Others have found effects of the parallel construct of power: correlational research shows that conspiracy beliefs are associated with perceived powerlessness23,82,83,84, and powerlessness might explain why conspiracy belief is somewhat higher among those with less education85. However, there is no experimental evidence that causally links power to conspiracy beliefs.

Like the need for control and power, the need for belonging is a well-established human drive86. It might seem paradoxical that a need for belonging could be implicated in people’s willingness to believe conspiracy theories given that ‘conspiracy theorists’ are frequently targets for stigma and ridicule. However, the internet has realigned traditional notions of inclusion and exclusion. In the face of stigma, people turn to supportive sub-communities to provide emotional and social ballast87,88, and these sub-communities are easy to find on social media. People might choose to engage with reinforcing online conspiracist communities for social nourishment when they feel isolated or lonely89. Evidence that conspiracy beliefs are higher among those experiencing isolation, loneliness and rejection66,67,90 reinforces the notion that people might be drawn to conspiracy theories to nourish a need for belonging.

Related to the need for belonging is the need for self-esteem. Despite the risk of stigma, subscribing to conspiracy theories might help people feel clever or special. At the heart of many conspiracy theories are several presumptions that are potentially self-enhancing: that those who believe these theories have access to secret knowledge that the mainstream is not sophisticated enough to access (the ‘do your research’ argument); that those who believe conspiracy theories are flexible free-thinkers, compared to the blinkered or sheep-like minority (the ‘wake up’ argument); and that those who believe conspiracy theories are on a critical mission and represent a brave minority working to revolutionize how society operates (the ‘speaking truth to power’ argument)91. Although there is no empirical evidence for these self-enhancing benefits, research has shown that conspiracy beliefs increase when one’s personal image is threatened92 and are somewhat higher among those who have a strong need for uniqueness93,94.

Finally, there is emerging evidence that conspiracy beliefs satisfy a desire for entertainment. Certainly, there is a large viewership for online conspiracy channels — many of which seem explicitly geared towards fun and entertainment — and many thrillers and dramas use conspiracies as a plot device owing to the sense of mystery and puzzle-solving that they evoke. Indeed, there is empirical evidence that conspiracy theories satisfy a desire for entertainment: conspiracist narratives were rated as more entertaining than non-conspiracist texts, and people were more likely to believe conspiracy theories that they found entertaining95.

The personality approach

Consistent with the entertainment argument, conspiracy beliefs are positively associated with a trait-like disposition towards sensation-seeking95. This finding reinforces the notion that personality might play a part in understanding who believes in conspiracy theories (and why). Indeed, theoretical arguments have been advanced for how the Big Five personality variables could be used to create a profile of those who believe conspiracy theories. These arguments include that openness to experience should have a role in conspiracy belief via the tendency to seek novel and unusual ideas96, that those low in agreeableness will harbour levels of suspicion and antagonism that characterize many conspiracy beliefs96,97,98,99 and that people high in neuroticism are more likely to experience uncertainty and anxiety, both of which characterize those who believe conspiracy theories100,101. However, two meta-analyses found mostly non-significant relationships between conspiracy beliefs and Big Five variables; the largest correlation (between conspiracy beliefs and agreeableness) was only –0.0746,102 (Fig. 2).

More fruitful have been efforts to link conspiracy beliefs with the Dark Triad: narcissism92,94,103, Machiavellianism58,104 and psychopathy37,58. All three Dark Triad traits are associated with conspiracy belief, which suggests that those who believe conspiracy theories have relative disregard for the interests of others. The ‘selfish actor’ model of those who believe conspiracy theories has been reinforced by research during the COVID-19 pandemic: people who endorsed COVID-19 conspiracy theories were more likely to stockpile105 and less likely to engage in actions that protected others (such as social distancing)10,106,107,108. Furthermore, endorsement of COVID-19 conspiracy theories was positively associated with anxiety about one’s own health and negatively associated with anxiety about the health of others108,109.

The developmental approach

Finally, although there has been progress in creating measures of conspiracy belief suitable for children and adolescents110, there has been little research on how conspiracy beliefs develop across the lifespan. Some have suggested that developmental experiences can affect willingness to believe conspiracy theories owing to their role in shaping attachment styles. For example, one study found that conspiracy beliefs were associated with anxious but not avoidant attachment111. However, another study found the opposite pattern112. Although these associations with anxious and/or avoidant attachment styles suggest that the propensity to believe conspiracy theories might be rooted in early childhood experiences, the conflicting results highlight the need for further study of the relationship between attachment and conspiracy belief. More generally, it is clear that research on the developmental aspects of conspiracy beliefs is in its infancy and should be a priority for research going forward.

Summary of individual-level factors

Hundreds of studies have investigated conspiracy theories at the individual level, many of which have been published in the past 3 years. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is still a tendency for these research streams to be siloed within disciplinary boundaries. In the early days of understanding a phenomenon this is not always a problem: after all, diverse disciplinary norms bring diverse perspectives, methodologies and theoretical approaches. Having said that, it is time for greater cross-disciplinary interaction in the study of conspiracy beliefs, and signs are positive in this regard: references from the 2020s suggest an increase in interdisciplinary collaborations, particularly between cognitive and social perspectives.

Inspection of Fig. 2 suggests some dead ends: there has been disproportionate interest in Big Five personality explanations, which have amounted to little in terms of explaining conspiracy beliefs. Furthermore, the field has suffered from methodological narrowness: there has been a heavy reliance on cross-sectional correlational studies, and where experiments have been conducted they often relied on laboratory-based paradigms with questionable generalizability and reproducibility. There is currently little in the way of secondary analyses of big data, research that tracks conspiracy beliefs over time, or developmental approaches. In the past 3 years these methodological choices have been partly dictated by the need for quick answers to the pressing problems associated with the COVID-19 public health crisis. But as this urgency fades, and as individual researchers coalesce into global research consortia, there will be more capacity for ambitious, large-scale longitudinal research.

Intergroup dynamics

An implication of the individual-level approach is that there are some people who are prone to believing conspiracy theories, and others who are not. By contrast, an intergroup approach highlights the extent to which everybody is prone to conspiracy theories depending on the sociohistorical context. Indeed, according to the adaptive conspiracism hypothesis4, the predisposition to believe conspiracy theories evolved as an adaptive tendency to be alert to — and to protect against — hostile coalitions or outgroups. Although these evolutionary underpinnings are difficult to prove (or falsify) the adaptive conspiracism hypothesis reinforces an uncontroversial point: by definition, conspiracy theories involve beliefs about the actions and agendas of coalitions of individuals, and they frequently have an intergroup element that crosses ideological, national, ethnic, religious or political fault lines. Conspiracy theories alert group members to potential threats, and can be used to rationalize ingroup aggression towards others113. This feedback loop, whereby feelings of victimhood simultaneously reinforce and are used to weaponize conspiracy theories, can be extremely dangerous (Box 1).

According to social identity theory, intergroup context shapes appraisals of information114. Salient intergroup contexts lead to a perceived enhancement of ingroup similarities and outgroup differences, which biases perceptions of whether a message is truthful and well intentioned115. In line with this perspective, an individual’s conspiracy belief is partly influenced by the extent to which other group members also believe that conspiracy theory116. Furthermore, social identity theory is based on the simple observation that there is a general bias towards wanting to think the best of groups to which one belongs117,118. A simple extrapolation from this notion is that people might be more likely to believe outgroups are capable of sinister acts of collusion compared with ingroups.

Examples of this phenomenon abound. In the 2000s, numerous polls revealed massive international differences in subscription to 9/11 conspiracy theories: whereas 22% of Canadians endorsed the notion that 9/11 was an inside job orchestrated by the government of the USA, 78% of individuals in seven Muslim countries supported this view119 (see also ref.120). Similarly, Chinese participants were much more likely to endorse the statement ‘The American government is secretly conspiring to harm China’ than ‘The Chinese government is secretly conspiring to harm America’; but the reverse is true for American participants121. Finally, followers of New Age spiritual practices are more likely than Christian people to believe the conspiracy that the Catholic Church kept secret Jesus’ marriage to Mary Magdalene, and that there is a secret organization protecting the ‘holy lineage’ that flowed from that union122. Clearly, group loyalties powerfully affect which conspiracy theories people are willing to believe123,124,125 to the point that one’s choice of conspiracy theories can signal group loyalties126. Furthermore, there is evidence that people’s choices of which coalitions to accuse of secret, malicious activity are motivated by system justification: people might blame negative events on outgroups or malevolent actors within the group127,128 to preserve the notion that their own social system is fair and legitimate.

The adaptive conspiracism hypothesis4 suggests that conspiracy theories evolved to help manage outgroup threats. Evidence that some conspiracy theories are triggered by feelings of intergroup threat and powerlessness aligns with this argument. For example, in Indonesia, anti-Western conspiracy theories are correlated with self-reported perceptions of threat and the perception that Western influences have fundamentally changed Muslim identity129. Similarly, intergroup conspiracy theories are associated with victimhood-based social identities, perceptions of relative deprivation and heightened rumination about historical trauma20,130,131. Importantly, the role of threat has also been demonstrated experimentally: when participants in Indonesia read an article designed to increase intergroup threat, their endorsement of anti-Western conspiracy theories was higher relative to a low-threat condition132.

The notion that identity vulnerability is a precursor of conspiracy belief is also reinforced by work on collective narcissism. Collective narcissism reflects fragile group self-esteem: endorsement of the ingroup’s greatness combined with a sense that the group is not valued enough by others (for example, “Not many people seem to fully understand the importance of the Polish nation”). Measures of collective narcissism (but not national identification) are associated with a range of defensive responses, including endorsement of intergroup conspiracy theories in which the ingroup is a target of outgroup aggression133,134,135 (Fig. 2).

From a social identity perspective, collective perceptions should predict endorsement of explicitly intergroup conspiracy theories more strongly than individual processes. For example, research in the Middle East and Africa suggests that endorsement of anti-Western and antisemitic conspiracy theories were associated with (self-reported) collective political consciousness, much more so than by individual feelings of personal control79. Accordingly, some theorists caution against individual-level interventions, arguing instead that conspiracy theories are a form of motivated collective cognition136.

In sum, there is a growing awareness that conspiracy theories cannot be examined exclusively as an individual-level phenomenon, but the empirical base for the intergroup level of analysis is still emergent. One strength of the research reviewed above is its global and temporal reach: compared with research on individual-level factors, research at the intergroup level is more likely to be situated within countries outside Western, industrialized contexts, and more likely to grapple with collective history and collective memory. However, like individual-level research, the field is overly reliant on cross-sectional, correlational research. A relative scarcity of experimental evidence limits claims of causality, and thereby the potential for interventions that target the intergroup level.

International differences

Over the past 5 years there has been growth in understanding of how conspiracy beliefs are shaped by macro-forces embedded in a nation, such as culture, economic variables and trust-sensitive political realities. Early attempts to identify international differences in conspiracy beliefs took a conceptual or anecdotal approach rather than a truly comparative approach. For example, one paper137 drew on observations of child-rearing practices, sexual mores and norms of secrecy to make the case that the “Arab–Iranian–Muslim Middle East” created a culture of conspiracist thinking that could be understood through a psychoanalytic frame. Also influenced by psychoanalytic theory was the case that politics in the USA (and particularly conservative politics) is geared towards suspicious discontent and conspiracy theorizing (a culturally embedded ‘paranoid style’)138.

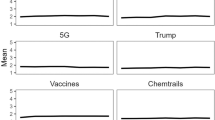

It is only in the past 5 years that scholars have begun collecting and interpreting data across multiple nations, with the aim of drawing empirically grounded conclusions about which countries are most prone to conspiracy beliefs (and why). In two cross-national datasets, participants rated their agreement with globally recognized conspiracy theories (for example, that the Moon landing was faked or that 9/11 was an inside job)139,140. Three other datasets141,142,143 used measures that assess an overall conspiracist mindset or worldview but do not make reference to any single conspiracy theory (for example “events which superficially seem to lack a connection are often the result of secret activities”98 or “I think that the official version of the events given by the authorities very often hides the truth”)144.

Unfortunately, these studies do not provide a strong foundation for conclusions about the effects of macro-factors on conspiracy beliefs because the datasets are too small to include relevant controls. Many nation-level factors are highly inter-correlated145 so it is statistically unreliable to enter more than one group-level variable in a regression at a time. Consequently, scholars are forced to examine bivariate correlations, which might be an artefact of covariation with a latent third variable rather than a ‘real’ relationship. Thus, statistically significant effects must be interpreted with caution and should not be over-interpreted. However, confidence in a relationship grows when it replicates across multiple datasets using different measures, replicates at both the group and individual level of analysis, and can plausibly be explained by theory.

Moreover, some macro-variables have more explanatory power when measured at the individual level (for example, as perceptions or individual orientations) than when measured using genuinely group-level data. For example, it would make theoretical sense that the cultural variable of uncertainty avoidance146 would predict conspiracy beliefs, given the demonstrated associations between epistemic anxiety and conspiracy beliefs30. However, although individuals who self-report uncertainty avoidance are higher in conspiracy belief, there is limited evidence that cultures with high levels of uncertainty avoidance are prone to believing conspiracies145. Similarly, individual perceptions of economic inequality within a nation are robustly associated with conspiracy beliefs147, but the pattern is not reliably observed when objective levels of inequality (such as the GINI coefficient143) are used. Finally, people with stronger collectivist (versus individualist) orientations have higher conspiracy beliefs10,141. There is some evidence that this pattern replicates at the national level: in most (but not all) cross-national datasets conspiracy belief is higher in collectivist (versus individualist) countries145. However, the mechanism underlying these results remains unclear. One possibility is that those with a collectivist orientation are more likely to provide relational explanations for random events and to rely on unofficial sources of information as proxies for reality10,141, but this explanation remains to be tested in relation to conspiracy theories.

To date, researchers have identified only two nation-level variables that consistently predict conspiracy beliefs across multiple datasets: economic vitality and corruption. First, countries with lower GDP per capita are more likely to endorse conspiracy theories143. This dovetails with political science research showing that trust in government tends to increase when the economy is strong and decline when the economy struggles148,149,150,151,152. Drawing on institutional theories153 and democratic theories154, scholars have argued that economic vitality is a proxy for government competence, and so a valid indicator of whether the government can be trusted. Somewhat consistent with this notion, individual-level data show that people believe conspiracy theories more when their perceptions of current and future economic performance within their nation is relatively poor143.

Second, conspiracy beliefs are higher in countries that are relatively high on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index145,155. These nation-level data dovetail with individual-level data on anomie: conspiracy beliefs are higher when people feel that social bonds of trust are deteriorating108. However, GDP per capita and the Corruption Perceptions Index are highly correlated156, so it is difficult to disentangle whether one or both are the ‘active ingredients’ shaping conspiracy beliefs.

Another macro-level factor that could potentially contribute to conspiracy belief is where a nation lies on the spectrum of democracy versus authoritarianism. Where electoral processes are distorted, civil liberties restricted and official media are mouthpieces for propaganda, a conspiracist worldview might be less irrational and more akin to functional cynicism. Indeed, members of countries that score higher on the Democracy Index (as curated by the Economist Intelligence Unit) tend to be less prone to believing conspiracy theories than those in more authoritarian regimes145. However, interpreting the robustness of this relationship is not easy. On one hand, this association is less consistent than the associations with GDP per capita and corruption perceptions. On the other hand, the relationship between conspiracy belief and the Democracy Index might be underestimated, because participants from authoritarian nations might be wary of revealing true levels of suspicion about the actions and motives of elite institutions within their country.

Integrating levels of understanding

A critical mass of research exists on drivers of conspiracy beliefs at micro (individual), meso (intergroup) and macro (national) levels of analysis, but these typically operate as discrete bodies of literature. Compartmentalization of literature is not necessarily a problem: it is natural (and sometimes beneficial) for levels of analysis to have their own language, approaches and theoretical touchstones. However, it is reasonable to ask how the micro, meso and macro explanations of conspiracy beliefs relate to each other, and to consider whether they can be integrated into a cohesive whole.

In trying to answer these questions, we recommend lowering expectations that Fig. 1 can be turned into a neat and tidy conceptual model, or that relationships between the levels can be captured empirically. Hygienic models where constructs relate in predictable and elegant ways might do a disservice to the complexity of the phenomenon at hand, particularly given that the psychology of conspiracy beliefs could change dramatically depending on the content of the conspiracy theory18. For example, it might not be reasonable to expect that the same model applies to conspiracies about a New World Order, Jeffrey Epstein and vaccines. Rather than envisaging unidirectional arrows between levels, conspiracy theories might be better understood in terms of a systems model where micro, meso and macro levels mutually reinforce each other in complex and recursive patterns that shift depending on the conspiracy domain.

That said, theory and prior research suggest certain testable propositions about how different levels might relate to each other, which we lay out below. All these pathways involve top-down processes, where more abstract, higher levels contextualize, shape or moderate lower-level factors. This does not rule out bottom-up processes; micro factors could cause meso or macro processes, analogous to a series of dots forming a gestalt whole in a pointillist painting. However, the theories we draw on are more consistent with top-down processes, and the flow from macro to micro processes is consistent with the logic of multilevel analyses in other literatures.

First, although we are not familiar with any research that has explicitly addressed ways in which macro processes (such as economic conditions and culture) might shape intergroup processes with regard to conspiracy theories, there is theoretical precedent to make the case. According to the adaptive conspiracism hypothesis4, socio-ecological factors such as economic crises can cue evolved readiness to attribute events to the deliberate actions of enemy groups. From this perspective, macro-level factors might trigger latent predispositions for intergroup conspiracy theories. Other literature can be drawn on to make a similar case that macro factors can shape whether (and in what way) conspiracy theories manifest at the intergroup level. For example, a key insight in the cross-cultural literature is that collectivist cultures are more prone to self-organizing by group identity than individualist cultures. By extension, it could be that culture shapes whether conspiracy theories coalesce into communities and intergroup contests (as opposed to conspiracy theories that are nurtured by individuals as ‘loners’). It is similarly possible that economic inequality and/or populist governments might nudge people towards seeing conspiracy theories through an intergroup lens (such as elites versus the rest, or the powerful versus the dispossessed; Box 2).

Second, it is possible to construct theoretically driven predictions about how intergroup context might moderate the relationship between individual-level factors and conspiracy beliefs. A fundamental premise of social identity theory is that, when an intergroup context is salient, strongly invested group members will converge around a fuzzy prototype of attitudes, behaviours and emotions defined by the group identity114,115. In other words, strong intergroup contexts trump individual-level variables in terms of shaping attitudes and behaviour. A simple, testable prediction is that the role of individual-level factors in explaining conspiracy beliefs will be weaker when intergroup factors are more intense, for example, in conditions where there is intergroup threat, strong ingroup identification, and/or collective cognitions around historical victimization.

Extrapolating this logic to the macro level, it could also be argued that individual-level factors will be less diagnostic when there are strong nation-level contexts (for example, in nations with high levels of corruption or economic dysfunction). However, the opposite prediction also seems sustainable: nation-level conditions might provide a backdrop of mistrust or dissatisfaction, which crystallize into conspiracy theories among those who have individual psychologies that predispose them to doing so. From this perspective, both nation-level and individual-level factors might be mutually reinforcing. In other words, micro factors might be the seeds of conspiracist thinking, whereas macro factors provide the fertile ground from which they grow.

Finally, it is plausible to devise a cascade or trickle-down model where conditions established at the macro level (such as cultural, economic or governance factors) help to shape factors at the meso level, which in turn influence factors at the micro level. For example, it could be that certain groups will feel marginalized within the specific power structure of their society, which then cascades down to create unmet psychological needs (such as deficits in feelings of control, power or epistemic certainty).

Although the above propositions are informed by theory, they are still speculative and lack an empirical basis. This should not be surprising: operating at more than one level of analysis simultaneously is not easy, often requiring extensive funding and always requiring methodological and theoretical virtuosity. Because it is too early to run sense-checks on the plausibility of the ideas raised above, we are at the somewhat unsatisfactory stage of presenting multiple pathways (some of which are contradictory). However, this also presents an opportunity by opening new questions and fields of enquiry for future researchers in this space.

Summary and future directions

In this Review, we have synthesized the literature on the interpersonal, intergroup and nation-level factors that drive conspiracy beliefs. To date, there is far more research documenting the causes of conspiracy beliefs than research that seeks to reduce conspiracy beliefs and their negative effects (Box 3). This is partly because some of the most-researched factors lead to an intellectual cul-de-sac: if the problem lies in factors that are relatively hard to influence — such as people’s pathologies, thinking styles or personalities — then this limits the extent to which the problem can be overcome. In addition to providing a more complete understanding of conspiracy beliefs, a multilevel approach suggests possible solutions, and the next generation of research in this space should examine interventions more directly. That is, future research should look for ways to reduce conspiracy theorizing, or at least to break the link between conspiracy beliefs and behaviours that are destructive for individuals and societies.

Future research should also test the cross-national generalizability of individual-level predictors that have been established in the existing literature. Testing the extent to which established correlates drawn from exclusively Western samples replicate in other parts of the world is important both theoretically and practically. The few attempts to test such generalizability have been revealing. For example, there is evidence that the link between conspiracy belief and climate scepticism — once considered universal — is especially pronounced in the USA139. Theoretically, this finding adds nuance to assumptions that climate scepticism is an expression of a conspiracist worldview, and has implications for understanding the interplay between individual-level and nation-level factors in shaping climate scepticism. The practical benefit of cross-national research is that it allows practitioners, communicators and policy-makers to understand the psychological correlates of conspiracy theorizing in their own regions so that they are better equipped to devise and implement interventions.

Finally, a truly multilevel approach to understanding conspiracy theories requires cosmopolitanism not only in theories, methods and approaches, but also in terms of how academics situate themselves, tonally. Migrating between micro-, meso- and macro-level factors requires an empathic shift as much as an epistemic shift. When scholars have focused on the individual level, the tone has drifted towards a deficit model defined by what those who believe conspiracy theories lack: they have ‘dark’ personalities, are prone to clinical disorders, demonstrate illogical ways of thinking, and have unmet psychological needs and selfish orientations. At the meso level, there is an emphasis on the destructive nature of conspiracies as a tool of prejudice and conflict. But analysis at the macro level suggests a more compassionate orientation: communities sometimes learn to mistrust elites because those elites cannot be trusted, and people are doing their best in difficult circumstances to make sense of ambiguous events.

This emphasizes the importance of being reflective about our academic stance: rather than seeing ourselves as calm and dispassionate arbiters of reasonableness, we must remember that the inherent apparent reasonableness of official accounts of events might shift depending on the sociopolitical culture within which one is situated. This creates a kaleidoscopic moral universe: conspiracy theories are both illogical and logical; truth is both sacred and relative; conspiracy beliefs do harm and they have the potential to meet important psychological needs. Scholars might find themselves toggling between a need to fight against destructive mistruths, and sensitivity to the notion that the best long-term solution to systemic mistrust is to demonstrate authentic trustworthiness in political, economic and institutional systems.

References

Gruber, I. D. The American revolution as a conspiracy: the British view. William Mary Q. 26, 360–372 (1969).

Uscinski, J. et al. Have beliefs in conspiracy theories increased over time? PLoS ONE 17, e0270429 (2022).

Uscinski, J. E. & Parent, J. M. American Conspiracy Theories (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014).

van Prooijen, J.-W. & van Vugt, M. Conspiracy theories: evolved functions and psychological mechanisms. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13, 770–788 (2018). This article argues that conspiracy beliefs are part of an evolved psychological mechanism aimed at detecting hostile groups.

Goertzel, T. Conspiracy theories in science: conspiracy theories that target specific research can have serious consequences for public health and environmental policies. EMBO Rep. 11, 493–499 (2010).

Jolley, D. & Douglas, K. M. The social consequences of conspiracism: exposure to conspiracy theories decreases intentions to engage in politics and to reduce one’s carbon footprint. Br. J. Psychol. 105, 35–56 (2014). This article is one of the first experimental demonstrations of the effects of conspiracy theories on people’s attitudes and intentions in important societal domains.

Lewandowsky, S., Gignac, G. E. & Oberauer, K. The robust relationship between conspiracism and denial of (climate) science. Psychol. Sci. 26, 667–670 (2015).

Lewandowsky, S., Oberauer, K. & Gignac, G. E. NASA faked the moon landing — therefore, (climate) science is a hoax: an anatomy of the motivated rejection of science. Psychol. Sci. 24, 622–633 (2013).

Uscinski, J. E., Douglas, K. & Lewandowsky, S. in Oxford Research Encyclopedia Of Climate Science (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017).

Biddlestone, M., Green, R. & Douglas, K. M. Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID‐19. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 59, 663–673 (2020).

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A. & Fielding, K. S. The psychological roots of anti-vaccination attitudes: a 24-nation investigation. Health Psychol. 37, 307–315 (2018). This study finds strikingly strong relationships between conspiracy worldview and anti-vaccination attitudes in a multi-national sample.

Jolley, D. & Douglas, K. M. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS ONE 9, e89177 (2014).

Lewandowsky, S., Gignac, G. E. & Oberauer, K. The role of conspiracist ideation and worldviews in predicting rejection of science. PLoS ONE 8, e75637 (2013).

Pummerer, L. et al. Conspiracy theories and their societal effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 13, 49–59 (2022).

Winter, K., Pummerer, L., Hornsey, M. J. & Sassenberg, K. Pro-vaccination subjective norms moderate the relationship between conspiracy mentality and vaccination intentions. Br. J. Health Psychol. 27, 390–405 (2022).

van Prooijen, J.-W., Etienne, T. W., Kutiyski, Y. & Krouwel, A. P. M. Conspiracy beliefs prospectively predict health behavior and well-being during a pandemic. Psychol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721004438 (2021).

Tangherlini, T. R., Shahsavari, S., Shahbazi, B., Ebrahimzadeh, E. & Roychowdhury, V. An automated pipeline for the discovery of conspiracy and conspiracy theory narrative frameworks: bridgegate, pizzagate and storytelling on the web. PLoS ONE 15, e0233879 (2020).

Sternisko, A., Cichocka, A. & Van Bavel, J. J. The dark side of social movements: social identity, non-conformity, and the lure of conspiracy theories. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 35, 1–6 (2020).

Imhoff, R., Dieterle, L. & Lamberty, P. Resolving the puzzle of conspiracy worldview and political activism: belief in secret plots decreases normative but increases nonnormative political engagement. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 12, 71–79 (2021).

Bilewicz, M., Winiewski, M., Kofta, M. & Wójcik, A. Harmful ideas, the structure and consequences of anti-Semitic beliefs in Poland. Polit. Psychol. 34, 821–839 (2013).

Jolley, D., Meleady, R. & Douglas, K. M. Exposure to intergroup conspiracy theories promotes prejudice which spreads across groups. Br. J. Psychol. 111, 17–35 (2020).

Basit, A. Conspiracy theories and violent extremism: similarities, differences and the implications. Count. Terrorist Trends Analyses 13, 1–9 (2021).

Abalakina‐Paap, M., Stephan, W. G., Craig, T. & Gregory, W. L. Beliefs in conspiracies. Polit. Psychol. 20, 637–647 (1999). This is one of the first studies of the psychological correlates of conspiracy beliefs.

Mari, S. et al. Conspiracy theories and institutional trust: examining the role of uncertainty avoidance and active social media use. Polit. Psychol. 43, 277–296 (2022).

Hornsey, M. J. & Fielding, K. S. Attitude roots and Jiu Jitsu persuasion: understanding and overcoming the motivated rejection of science. Am. Psychol. 72, 459–473 (2017).

Iyengar, S. & Massey, D. S. Scientific communication in a post-truth society. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 7656–7661 (2018).

Pigden, C. Popper revisited, or what is wrong with conspiracy theories? Phil. Soc. Sci. 25, 3–34 (1995).

Dentith, M. R. X. Conspiracy theories on the basis of the evidence. Synthese 196, 2243–2261 (2019).

Keeley, B. L. Of conspiracy theories. J. Phil. 96, 109 (1999).

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M. & Cichocka, A. The psychology of conspiracy theories. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 26, 538–542 (2017). This article articulates a framework for the motivational underpinnings of conspiracy beliefs.

Georgiou, N., Delfabbro, P. & Balzan, R. Conspiracy-beliefs and receptivity to disconfirmatory information: a study using the BADE task. SAGE Open 11, 21582440211006131 (2021).

van der Wal, R. C., Sutton, R. M., Lange, J. & Braga, J. P. N. Suspicious binds: conspiracy thinking and tenuous perceptions of causal connections between co-occurring and spuriously correlated events. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 970–989 (2018).

van Prooijen, J.-W., Douglas, K. M. & De Inocencio, C. Connecting the dots: illusory pattern perception predicts belief in conspiracies and the supernatural. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 320–335 (2018).

Leman, P. & Cinnirella, M. A major event has a major cause: evidence for the role of heuristics in reasoning about conspiracy theories. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 9, 18–28 (2007).

McCauley, C. & Jacques, S. The popularity of conspiracy theories of presidential assassination: a Bayesian analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 37, 637–644 (1979).

Wood, M. J., Douglas, K. M. & Sutton, R. M. Dead and alive: beliefs in contradictory conspiracy theories. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 3, 767–773 (2012).

Georgiou, N., Delfabbro, P. & Balzan, R. Conspiracy beliefs in the general population: the importance of psychopathology, cognitive style and educational attainment. Pers. Individ. Dif. 151, 109521 (2019).

Swami, V., Voracek, M., Stieger, S., Tran, U. S. & Furnham, A. Analytic thinking reduces belief in conspiracy theories. Cognition 133, 572–585 (2014).

Georgiou, N., Delfabbro, P. & Balzan, R. Conspiracy theory beliefs, scientific reasoning and the analytical thinking paradox. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 35, 1523–1534 (2021).

Ballová Mikušková, E. Conspiracy beliefs of future teachers. Curr. Psychol. 37, 692–701 (2018).

Swami, V. & Barron, D. Rational thinking style, rejection of coronavirus (COVID-19) conspiracy theories/theorists, and compliance with mandated requirements: direct and indirect relationships in a nationally representative sample of adults from the United Kingdom. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 15, 18344909211037385 (2021).

Stanley, M. L., Barr, N., Peters, K. & Seli, P. Analytic-thinking predicts hoax beliefs and helping behaviors in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Think. Reason. 27, 464–477 (2021).

Kantorowicz-Reznichenko, E., Folmer, C. R. & Kantorowicz, J. Don’t believe it! A global perspective on cognitive reflection and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 pandemic. Pers. Individ. Dif. 194, 111666 (2022).

Lantian, A., Bagneux, V., Delouvée, S. & Gauvrit, N. Maybe a free thinker but not a critical one: high conspiracy belief is associated with low critical thinking ability. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 35, 674–684 (2021).

Ståhl, T. & van Prooijen, J.-W. Epistemic rationality: skepticism toward unfounded beliefs requires sufficient cognitive ability and motivation to be rational. Pers. Individ. Dif. 122, 155–163 (2018).

Stasielowicz, L. Who believes in conspiracy theories? A meta-analysis on personality correlates. J. Res. Pers. 98, 104229 (2022).

Brotherton, R. & French, C. C. Intention seekers: conspiracist ideation and biased attributions of intentionality. PLoS ONE 10, e0124125 (2015).

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., Callan, M. J., Dawtry, R. J. & Harvey, A. J. Someone is pulling the strings: hypersensitive agency detection and belief in conspiracy theories. Think. Reason. 22, 57–77 (2016).

Rizeq, J., Flora, D. B. & Toplak, M. E. An examination of the underlying dimensional structure of three domains of contaminated mindware: paranormal beliefs, conspiracy beliefs, and anti-science attitudes. Think. Reason. 27, 187–211 (2021).

Dieguez, S., Wagner-Egger, P. & Gauvrit, N. Nothing happens by accident, or does it? A low prior for randomness does not explain belief in conspiracy theories. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1762–1770 (2015).

Flaherty, E., Sturm, T. & Farries, E. The conspiracy of Covid-19 and 5 G: spatial analysis fallacies in the age of data democratization. Soc. Sci. Med. 293, 114546 (2022).

Brotherton, R. & French, C. C. Belief in conspiracy theories and susceptibility to the conjunction fallacy. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 28, 238–248 (2014). This study finds an association between a cognitive bias (the conjunction fallacy) and conspiracy beliefs.

Wabnegger, A., Gremsl, A. & Schienle, A. The association between the belief in coronavirus conspiracy theories, miracles, and the susceptibility to conjunction fallacy. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 35, 1344–1348 (2021).

Pytlik, N., Soll, D. & Mehl, S. Thinking preferences and conspiracy belief: intuitive thinking and the jumping to conclusions-bias as a basis for the belief in conspiracy theories. Front. Psychiat. 11, 568942 (2020).

So, S. H.-W., Siu, N. Y.-F., Wong, H.-L., Chan, W. & Garety, P. A. ‘Jumping to conclusions’ data-gathering bias in psychosis and other psychiatric disorders — two meta-analyses of comparisons between patients and healthy individuals. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 46, 151–167 (2016).

Furnham, A. & Grover, S. Do you have to be mad to believe in conspiracy theories? Personality disorders and conspiracy theories. Int. J. Soc. Psychiat. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640211031614 (2021).

Darwin, H., Neave, N. & Holmes, J. Belief in conspiracy theories. The role of paranormal belief, paranoid ideation and schizotypy. Pers. Individ. Dif. 50, 1289–1293 (2011).

March, E. & Springer, J. Belief in conspiracy theories: the predictive role of schizotypy, Machiavellianism, and primary psychopathy. PLoS ONE 14, e0225964 (2019).

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. How paranoid are conspiracy believers? Toward a more fine-grained understanding of the connect and disconnect between paranoia and belief in conspiracy theories. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 909–926 (2018).

Greenburgh, A. G., Liefgreen, A., Bell, V. & Raihani, N. Factors affecting conspiracy theory endorsement in paranoia. R. Soc. Open Sci. 9, 211555 (2022).

Alsuhibani, A., Shevlin, M., Freeman, D., Sheaves, B. & Bentall, R. P. Why conspiracy theorists are not always paranoid: conspiracy theories and paranoia form separate factors with distinct psychological predictors. PLoS ONE 17, e0259053 (2022).

Meuer, M. & Imhoff, R. Believing in hidden plots is associated with decreased behavioral trust: conspiracy belief as greater sensitivity to social threat or insensitivity towards its absence? J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 93, 104081 (2021).

Heiss, R., Gell, S., Röthlingshöfer, E. & Zoller, C. How threat perceptions relate to learning and conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19: evidence from a panel study. Pers. Individ. Dif. 175, 110672 (2021).

De Coninck, D. et al. Beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19: comparative perspectives on the role of anxiety, depression and exposure to and trust in information sources. Front. Psychol. 12, 646394 (2021).

Grzesiak-Feldman, M. Conspiracy thinking and state-trait anxiety in young Polish adults. Psychol. Rep. 100, 199–202 (2007).

Hettich, N. et al. Conspiracy endorsement and its associations with personality functioning, anxiety, loneliness, and sociodemographic characteristics during the COVID-19 pandemic in a representative sample of the German population. PLoS ONE 17, e0263301 (2022).

Poon, K.-T., Chen, Z. & Wong, W.-Y. Beliefs in conspiracy theories following ostracism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46, 1234–1246 (2020).

Marchlewska, M., Green, R., Cichocka, A., Molenda, Z. & Douglas, K. M. From bad to worse: avoidance coping with stress increases conspiracy beliefs. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 61, 532–549 (2022). This study demonstrates that people are drawn to conspiracy theories when they display maladaptive coping strategies.

Liekefett, L., Christ, O. & Becker, J. C. Can conspiracy beliefs be beneficial? Longitudinal linkages between conspiracy beliefs, anxiety, uncertainty aversion, and existential threat. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211060965 (2021). This rare longitudinal investigation of conspiracy beliefs finds that rather than satisfying psychological motives, conspiracy beliefs might only further frustrate them.

Whitson, J. A. & Galinsky, A. D. Lacking control increases illusory pattern perception. Science 322, 115–117 (2008).

Whitson, J. A., Kim, J., Wang, C. S., Menon, T. & Webster, B. D. Regulatory focus and conspiratorial perceptions: the importance of personal control. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 45, 3–15 (2019).

Whitson, J. A., Galinsky, A. D. & Kay, A. The emotional roots of conspiratorial perceptions, system justification, and belief in the paranormal. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 56, 89–95 (2015).

Stojanov, A., Bering, J. M. & Halberstadt, J. Does perceived lack of control lead to conspiracy theory beliefs? Findings from an online MTurk sample. PLoS ONE 15, e0237771 (2020).

Šrol, J., Ballová Mikušková, E. & Čavojová, V. When we are worried, what are we thinking? Anxiety, lack of control, and conspiracy beliefs amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 35, 720–729 (2021).

Douglas, K. M. & Leite, A. C. Suspicion in the workplace: organizational conspiracy theories and work-related outcomes. Br. J. Psychol. 108, 486–506 (2017).

Sullivan, D., Landau, M. J. & Rothschild, Z. K. An existential function of enemyship: evidence that people attribute influence to personal and political enemies to compensate for threats to control. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 98, 434–449 (2010).

van Prooijen, J.-W. & Acker, M. The influence of control on belief in conspiracy theories: conceptual and applied extensions. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 29, 753–761 (2015).

Hart, J. & Graether, M. Something’s going on here: psychological predictors of belief in conspiracy theories. J. Individ. Dif. 39, 229–237 (2018).

Nyhan, B. & Zeitzoff, T. Conspiracy and misperception belief in the Middle East and North Africa. J. Polit. 80, 1400–1404 (2018).

van Elk, M. & Lodder, P. Experimental manipulations of personal control do not increase illusory pattern perception. Collabra Psychol. 4, 19 (2018).

Stojanov, A. & Halberstadt, J. Does lack of control lead to conspiracy beliefs? A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 955–968 (2020).

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. in Routledge Handbook Of Conspiracy Theories (eds Butter, M. & Knight, P.) 192–205 (Routledge, 2020).

Tonković, M., Dumančić, F., Jelić, M. & Čorkalo Biruški, D. Who believes in COVID-19 conspiracy theories in Croatia? Prevalence and predictors of conspiracy beliefs. Front. Psychol. 12, 643568 (2021).

Pantazi, M., Papaioannou, K. & van Prooijen, J.-W. Power to the people: the hidden link between support for direct democracy and belief in conspiracy theories. Polit. Psychol. 43, 529–548 (2022).

van Prooijen, J.-W. Why education predicts decreased belief in conspiracy theories. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 31, 50–58 (2017).

Baumeister, R. F. & Leary, M. R. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529 (1995).

Schmitt, M. T. & Branscombe, N. R. The meaning and consequences of perceived discrimination in disadvantaged and privileged social groups. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 12, 167–199 (2002).

Nera, K., Jetten, J., Biddlestone, M. & Klein, O. ‘Who wants to silence us’? Perceived discrimination of conspiracy theory believers increases ‘conspiracy theorist’ identification when it comes from powerholders — but not from the general public. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12536 (2022).

Klein, C., Clutton, P. & Dunn, A. G. Pathways to conspiracy: the social and linguistic precursors of involvement in Reddit’s conspiracy theory forum. PLoS ONE 14, e0225098 (2019).

Graeupner, D. & Coman, A. The dark side of meaning-making: how social exclusion leads to superstitious thinking. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 69, 218–222 (2017).

Imhoff, R. & Bruder, M. Speaking (un-)truth to power: conspiracy mentality as a generalised political attitude. Eur. J. Pers. 28, 25–43 (2014).

Cichocka, A., Marchlewska, M. & Golec de Zavala, A. Does self-love or self-hate predict conspiracy beliefs? Narcissism, self-esteem, and the endorsement of conspiracy theories. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 7, 157–166 (2016). This study finds that narcissism plays a part in predicting conspiracy beliefs.

Lantian, A., Muller, D., Nurra, C. & Douglas, K. M. “I know things they don’t know!”: the role of need for uniqueness in belief in conspiracy theories. Soc. Psychol. 48, 160–173 (2017).

Kay, C. S. The targets of all treachery: delusional ideation, paranoia, and the need for uniqueness as mediators between two forms of narcissism and conspiracy beliefs. J. Res. Pers. 93, 104128 (2021).

van Prooijen, J.-W., Ligthart, J., Rosema, S. & Xu, Y. The entertainment value of conspiracy theories. Br. J. Psychol. 113, 25–48 (2022).

Swami, V. et al. Lunar lies: the impact of informational framing and individual differences in shaping conspiracist beliefs about the moon landings. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 27, 71–80 (2013).

Swami, V. & Coles, R. The truth is out there: belief in conspiracy theories. Psychologist 23, 560–563 (2010).

Bruder, M., Haffke, P., Neave, N., Nouripanah, N. & Imhoff, R. Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: conspiracy mentality questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 4, 225 (2013).

Swami, V. & Furnham, A. Examining conspiracist beliefs about the disappearance of Amelia Earhart. J. Gen. Psychol. 139, 244–259 (2012).

Hollander, B. A. Partisanship, individual differences, and news media exposure as predictors of conspiracy beliefs. J. Mass Commun. Q. 95, 691–713 (2018).

McGregor, I., Hayes, J. & Prentice, M. Motivation for aggressive religious radicalization: goal regulation theory and a personality×threat×affordance hypothesis. Front. Psychol. 6, 1325 (2015).

Goreis, A. & Voracek, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological research on conspiracy beliefs: field characteristics, measurement instruments, and associations with personality traits. Front. Psychol. 10, 205 (2019).

Gligorić, V. et al. The usual suspects: how psychological motives and thinking styles predict the endorsement of well-known and COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 35, 1171–1181 (2021).

Douglas, K. M. & Sutton, R. M. Does it take one to know one? Endorsement of conspiracy theories is influenced by personal willingness to conspire. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 544–552 (2011).

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. A bioweapon or a hoax? The link between distinct conspiracy beliefs about the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak and pandemic behavior. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 11, 1110–1118 (2020).

Bierwiaczonek, K., Kunst, J. R. & Pich, O. Belief in COVID‐19 conspiracy theories reduces social distancing over time. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 12, 1270–1285 (2020).

Bierwiaczonek, K., Gundersen, A. B. & Kunst, J. R. The role of conspiracy beliefs for COVID-19 health responses: a meta-analysis. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 46, 101346 (2022). This is one of the first meta-analyses on the psychology of conspiracy beliefs that analyses the role of conspiracy beliefs in responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hornsey, M. J. et al. To what extent are conspiracy theorists concerned for self versus others? A COVID-19 test case. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 51, 285–293 (2021).

Marinthe, G., Brown, G., Delouvée, S. & Jolley, D. Looking out for myself: exploring the relationship between conspiracy mentality, perceived personal risk and COVID-19 prevention measures. Br. J. Health Psychol. 25, 957–980 (2020).

Jolley, D., Douglas, K. M., Skipper, Y., Thomas, E. & Cookson, D. Measuring adolescents’ beliefs in conspiracy theories: development and validation of the adolescent conspiracy beliefs questionnaire (ACBQ). Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 39, 499–520 (2021).

Green, R. & Douglas, K. M. Anxious attachment and belief in conspiracy theories. Pers. Individ. Dif. 125, 30–37 (2018).

Leone, L., Giacomantonio, M., Williams, R. & Michetti, D. Avoidant attachment style and conspiracy ideation. Pers. Individ. Dif. 134, 329–336 (2018).

Chayinska, M. & Minescu, A. “They’ve conspired against us”: understanding the role of social identification and conspiracy beliefs in justification of ingroup collective behavior. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 990–998 (2018).

Turner, J. C. Social Influence (Brooks/Cole, 1991).

Turner, J. C., Wetherell, M. S. & Hogg, M. A. Referent informational influence and group polarization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 28, 135–147 (1989).

Cookson, D., Jolley, D., Dempsey, R. & Povey, R. “If they believe, then so shall I”: perceived beliefs of the in-group predict conspiracy theory belief. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 24, 759–782 (2021).

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. C. in The Social Psychology Of Intergroup Relations (eds Austin, W. G. & Worchel, S.) 33–37 (Brooks/Cole, 1979).

Hornsey, M. J. Social identity theory and self-categorization theory: a historical review. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2, 204–222 (2008).

Sunstein, C. R. & Vermeule, A. Conspiracy theories: causes and cures. J. Polit. Phil. 17, 202–227 (2009). This article provides an early perspective on how to address the potentially harmful impact of conspiracy theories.

Gentzkow, M. A. & Shapiro, J. M. Media, education and anti-Americanism in the muslim world. J. Econ. Perspect. 18, 117–133 (2004).

van Prooijen, J.-W. & Song, M. The cultural dimension of intergroup conspiracy theories. Br. J. Psychol. 112, 455–473 (2021).

Newheiser, A.-K., Farias, M. & Tausch, N. The functional nature of conspiracy beliefs: examining the underpinnings of belief in the Da Vinci code conspiracy. Pers. Individ. Dif. 51, 1007–1011 (2011).

Van Prooijen, J.-W. & van Lange, P. A. M. in Power, Politics, And Paranoia. Why People Are Suspicious Of Their Leaders (eds van Prooijen, J. -W. & van Lange, P. A. M.) 237–253 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Anthony, A. & Moulding, R. Breaking the news: belief in fake news and conspiracist beliefs. Aust. J. Psychol. 71, 154–162 (2019).

Enders, A. M. & Smallpage, S. M. Who are conspiracy theorists? A comprehensive approach to explaining conspiracy beliefs. Soc. Sci. Q. 100, 2017–2032 (2019).

Smallpage, S. M., Enders, A. M. & Uscinski, J. E. The partisan contours of conspiracy theory beliefs. Res. Polit. 4, 205316801774655 (2017).

Mao, J.-Y., van Prooijen, J.-W., Yang, S.-L. & Guo, Y.-Y. System threat during a pandemic: how conspiracy theories help to justify the system. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 15, 183449092110570 (2021).

Jolley, D., Douglas, K. M. & Sutton, R. M. Blaming a few bad apples to save a threatened barrel: the system-justifying function of conspiracy theories. Polit. Psychol. 39, 465–478 (2018).

Mashuri, A., Zaduqisti, E., Sukmawati, F., Sakdiah, H. & Suharini, N. The role of identity subversion in structuring the effects of intergroup threats and negative emotions on belief in anti-West conspiracy theories in Indonesia. Psychol. Dev. Soc. 28, 1–28 (2016).

Pantazi, M., Gkinopoulos, T., Witkowska, M., Klein, O. & Bilewicz, M. “Historia est magistra vitae”? The impact of historical victimhood on current conspiracy beliefs. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 25, 581–601 (2022).

Skrodzka, M., Kende, A., Faragó, L. & Bilewicz, M. “Remember that we suffered!” The effects of historical trauma on anti-Semitic prejudice. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 52, 341–350 (2022).

Mashuri, A. & Zaduqisti, E. The effect of intergroup threat and social identity salience on the belief in conspiracy theories over terrorism in Indonesia: collective angst as a mediator. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 8, 24–35 (2015).

Cichocka, A., Marchlewska, M., Golec de Zavala, A. & Olechowski, M. ‘They will not control us’: ingroup positivity and belief in intergroup conspiracies. Br. J. Psychol. 107, 556–576 (2016).

Wang, X., Zuo, S.-J., Chan, H.-W., Chiu, C. P.-Y. & Hong, Y.-Y. COVID-19-related conspiracy theories in China: the role of secure versus defensive in-group positivity and responsibility attributions. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 15, 18344909211034928 (2021).

Golec de Zavala, A., Bierwiaczonek, K. & Ciesielski, P. An interpretation of meta-analytical evidence for the link between collective narcissism and conspiracy theories. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 47, 101360 (2022).

Krekó, P. in Routledge Handbook Of Conspiracy Theories (eds Butter, M. & Knight, P.) 242–256 (Routledge, 2020).

Zonis, M. & Joseph, C. M. Conspiracy thinking in the Middle East. Polit. Psychol. 15, 443–459 (1994).

Hofstadter, R. The paranoid style in American politics. Harper’s Magazine https://harpers.org/archive/1964/11/the-paranoid-style-in-american-politics/ (1964).

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A. & Fielding, K. S. Relationships among conspiratorial beliefs, conservatism and climate scepticism across nations. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 614–620 (2018).

YouGov-Cambridge centre. Globalism Project. YouGov https://yougov.co.uk/topics/yougov-cambridge/globalism-project (2020).

Adam-Troïan, J. et al. Investigating the links between cultural values and belief in conspiracy theories: the key roles of collectivism and masculinity. Polit. Psychol. 42, 597–618 (2021).

Imhoff, R. et al. Conspiracy mentality and political orientation across 26 countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 392–403 (2022). This is a large, multi-national investigation into the relationship between political ideology and conspiracy belief.

Hornsey, M. J. et al. Multinational data show that conspiracy beliefs are associated with the perception (and reality) of poor national economic performance. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2888 (2022).

Lantian, A., Muller, D., Nurra, C. & Douglas, K. M. Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: validation of a French and English single-item scale. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 29, 1–14 (2016).

Hornsey, M. J. & Pearson, S. Cross-national differences in willingness to believe conspiracy theories. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 47, 101391 (2022).

Minkov, M. & Hofstede, G. A replication of Hofstede’s uncertainty avoidance dimension across nationally representative samples from Europe. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 14, 161–171 (2014).

Salvador Casara, B. G., Suitner, C. & Jetten, J. The impact of economic inequality on conspiracy beliefs. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 98, 104245 (2022).

Foster, C. & Frieden, J. Crisis of trust: socio-economic determinants of Europeans’ confidence in government. Eur. Union. Polit. 18, 511–535 (2017).

van Erkel, P. & Meer, T. O. M. Macroeconomic performance, political trust and the Great Recession: a multilevel analysis of the effects of within-country fluctuations in macroeconomic performance on political trust in 15 EU countries, 1999–2011. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 55, 177–197 (2016).

Armingeon, K. & Ceka, B. The loss of trust in the European Union during the great recession since 2007: the role of heuristics from the national political system. Eur. Union. Polit. 15, 82–107 (2013).

Chanley, V. A., Rudolph, T. J. & Rahn, W. M. The origins and consequences of public trust in government: a time series analysis. Public Opin. Q. 64, 239–256 (2000).

Hetherington, M. J. The political relevance of political trust. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 92, 791–808 (1998).

Peters, B. Institutional Theory In Political Science 4th edn (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019).

Wroe, A. Economic insecurity and political trust in the United States. Am. Polit. Res. 44, 131–163 (2015).

Alper, S. & Imhoff, R. Suspecting foul play when it is objectively there: the association of political orientation with general and partisan conspiracy beliefs as a function of corruption levels. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506221113965 (2022).

Christos, P. et al. Corruption Perception Index (CPI), as an index of economic growth for European countries. Theor. Econ. Lett. 08, 524–537 (2018).

Kofta, M., Soral, W. & Bilewicz, M. What breeds conspiracy antisemitism? The role of political uncontrollability and uncertainty in the belief in Jewish conspiracy. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 118, 900–918 (2020). This is an investigation of antisemitic conspiracy theories and the role of political uncontrollability in driving these beliefs.

Kofta, M. & Slawuta, P. Thou shall not kill…your brother: victim−perpetrator cultural closeness and moral disapproval of Polish atrocities against Jews after the Holocaust. J. Soc. Issues 69, 54–73 (2013).

Nilsson, P.-E. Manifestos of white nationalist ethno-soldiers. Crit. Res. Religion 10, 221–235 (2022).

Bytwerk, R. L. Believing in “inner truth”: the protocols of the elders of Zion in Nazi propaganda, 1933–1945. Holocaust Genocide Stud. 29, 212–229 (2015).

Krouwel, A., Kutiyski, Y., van Prooijen, J.-W., Martinsson, J. & Markstedt, E. Does extreme political ideology predict conspiracy beliefs, economic evaluations and political trust? Evidence from Sweden. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 5, 435–462 (2017).