Abstract

Frailty in aging marks a state of decreased reserves resulting in increased vulnerability to adverse outcomes when exposed to stressors. This Perspective synthesizes the evidence on the aging-related pathophysiology underpinning the clinical presentation of physical frailty as a phenotype of a clinical syndrome that is distinct from the cumulative-deficit-based frailty index. We focus on integrating the converging evidence on the conceptualization of physical frailty as a state, largely independent of chronic diseases, that emerges when the dysregulation of multiple interconnected physiological and biological systems crosses a threshold to critical dysfunction, severely compromising homeostasis. Our exegesis posits that the physiology underlying frailty is a critically dysregulated complex dynamical system. This conceptual framework implies that interventions such as physical activity that have multisystem effects are more promising to remedy frailty than interventions targeted at replenishing single systems. We then consider how this framework can drive future research to further understanding, prevention and treatment of frailty, which will likely preserve health and resilience in aging populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Why do some older people die in the face of heatwaves and others do not? What has created the heightened risk of mortality from COVID-19 in older people? This vulnerability comes in part from the effects of chronic diseases and other health-related conditions that accumulate with increasing age. We hypothesize that it also results from what clinicians term ‘frailty’, a state of depleted reserve resulting in increased vulnerability to stressors that emerges during aging independently of any specific disease.

Definitions of frailty are abound. The two dominantly used are ‘phenotypic frailty’, where a validated clinical presentation marks a distinct clinical syndrome and pathophysiology1,2, and a ‘deficit accumulation model’ frailty index, which summarizes the presence of multiple clinically identified diseases, their clinical and laboratory manifestations and consequences, and risk factors into a composite index for risk prediction3,4. These two distinct conceptualizations both carry the same nomenclature and both predict high mortality and institutionalization risk, but they denote different theory, etiologies, measures and possibly processes, and identify considerably different populations and different targets of intervention5. Other definitions of frailty have integrated additional constructs, particularly cognitive frailty, as proposed by the International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics/International Academy on Nutrition and Aging (IAGG/IANA)6,7. However, such integration has the potential to obscure meaningful differences, as exemplified by the observation that 22% of people with Alzheimer’s disease had no physical indicators of frailty8. This is reinforced by clinical encounters with older adults who are physically robust but cognitively frail and vice versa. Accordingly, we view other types of frailty, whether they are cognitive, emotional or psychosocial frailty, as important but distinct constructs that can be most fruitfully measured separately from each other and from phenotypic frailty. Both phenotypically identified frailty and the frailty index, finally, also link to other constructs in gerontology, notably, ‘allostasis’, ‘homeostasis’, ‘robustness’, ‘reserve’ and ‘resilience’. A thorough disambiguation of these related concepts is beyond our scope, but provisional definitions are given in Box 1 and considered below.

The syndrome of phenotypic frailty—henceforth termed ‘physical frailty’—is the focus of this Perspective. Clinical presentation of the phenotype denotes a distinctive high-risk clinical state that indicates decreased reserves and high vulnerability to stressors. The state is clinically recognizable through the presence of three or more of five key clinical signs and symptoms: weakness, slow walking speed, low physical activity, fatigue or exhaustion, and unintentional weight loss (Fig. 1 and Box 1)1,2. Prevalence in people 65 years and older varies across populations, with a predominant rate of 7–10% in community-dwelling older adults, which increases to over 25% in those over 85 years old1,2,9,10,11. The constellation of three or more criteria constitutes a diagnosis of frailty, which has been validated to predict adverse outcomes including death, disability, loss of independence, falls, hospitalization, diminished response to disease-targeted therapies, higher risk of adverse outcomes with surgery and delayed recovery from illness1,2,12,13. Consistent with a clinical syndrome2, the phenotype is linked to specific pathophysiology. Physical frailty often presents without clinical diseases or disability, but it can also co-occur with disease and disability1,2,14,15 (Box 1).This is consistent with substantial research to disentangle multimorbidity, disability and frailty, which shows that these are distinct entities that can arise independently as well as be causally related16. Risks of frailty onset or progression are especially high in the face of stressors1, so it is considered to be a state of heightened vulnerability.

The schema depicts the clinical syndrome of physical frailty as an emergent property, at the highest level of the hierarchy, underlain by physiological modules (systems) at a smaller scale and cellular/molecular modules (systems) at an even smaller scale. Gold circles represent the three major physiological modules (systems) with the most evidence of interactions and the most evidence of a relationship with frailty. Orange ovals represent submodules (subsystems) within these three larger modules. Stressors from age-related biological changes at the cellular/molecular scale, represented in purple ovals, likely underlie dysregulation of the physiological modules represented above, which also interact with each other. The aggregate physiotype of dysregulation (dark orange oval) is associated with both the phenotype of physical frailty, in the top oval, and the vulnerability associated with its state. Adapted from ref. 106.

In contrast, the deficit accumulation model is conceptually based on the clinical observation that a multiplicity of clinical problems in a patient creates aggregate risk of poor outcomes, such as mortality and institutionalization. This has been operationalized as a ‘frailty index’, which calculates the percentage of conditions or ‘deficits’ identified clinically, relative to the number assessed, including diseases, symptoms, signs, impairments, disabilities and measured functional limitations, social settings, physical activity, mental health, cognitive status, self-rated health and sometimes laboratory values3,4.

This article focuses on the pathophysiology of the syndrome of physical frailty, examining how the phenotype may emerge as a distinct state linked to severe dysregulation of key physiological and biological systems: the stress-response, metabolism and musculoskeletal systems. In healthy adults, multiple physiological systems function well and interact harmoniously in a complex dynamical system, as in a symphony, to maintain allostasis and homeostasis. However, as people age, individual physiological systems decline in their efficiency17 and communication between cells and between systems deteriorates18. We hypothesize that this results in a cacophony of multisystem dysregulation, which eventually crosses a severity threshold and precipitates a state of highly diminished function and resilience, physical frailty.

This hypothesis rests on a conceptualization of the physiological and biological pathways underlying health and resilience as linked elements of a complex dynamical system (see Box 1 for a glossary of terms and Box 2 for a brief introduction), with severe dysregulation of this system underlying physical frailty. While complex dynamical systems may sound formidable to some, the key insight is simply that one’s physiological state results from numerous interacting components at different temporal and spatial scales (for example, genes, cells, organs) that create a whole unpredictably more than the parts19. For analogy, consider a clenched fist as a state of the hand: there is no doubt that this state is contributed by cells and molecules. Nonetheless, the most important insights into that fist are likely to come from the hand’s structure (five digits, opposable thumb, muscle–bone–motor neuron structure) and from insight into the teleological control at a higher level (anger, aggression, evolutionary uses of hands, and so on). Applying a similar logic to physical frailty, knowing the state of all the underlying biological components may not additively sum to the overall state of health or accurately infer the integrated capabilities of the higher-level organism. This example illustrates the importance of hierarchy in complex dynamical systems, where interactions among nested and parallel levels of composition (for example, cells, tissues, physiology) contribute essentially to the overall function.

Thinking on complex dynamical systems offers additional compelling conceptual framework elements for characterizing physical frailty. Specifically, we summarize below, in a stepwise progression, evidence that the pathophysiology of frailty meets criteria for critical dysregulation of the complex dynamical system necessary for homeostasis: (1) physiology is modularly organized in healthy organisms, and numerous modules are dysfunctional in physical frailty; (2) the dysfunction is particularly apparent in the ability of the systems and modules to respond to stressors; (3) the dysfunction does not proceed independently in each system but rather is fundamentally about interactions among systems via feedback loops; (4) the impacts of the dysfunction are not linear but exhibit exponential and/or threshold effects; and (5) these dynamics can lead to critical transitions and abrupt shifts in physiological state. We then consider the biological hallmarks of aging18 that could diffusely affect all functions of this complex dynamical system and may be affected by the physiological dysfunctions associated with the phenotype itself. We conclude by considering implications and next-stage research agendas.

Physical frailty is an emergent state of a compromised complex dynamical system

We present here evidence that physical frailty in aging emerges as a compromised state of a dysregulated complex dynamical system. This evidence is presented progressively in terms of the criteria for complex dynamical systems: the modular systems and subsystems which function both independently and in joint feedforward and feedback regulation that characterizes such systems and is critical for managing allostasis and homeostasis; the evidence that such core regulatory systems associated with physical frailty co-regulate each other and their aggregate dysfunction is associated with the phenotype of frailty; that dysregulation of these multiple systems is made visible when challenged; that past a threshold of aggregate physiologic dysfunction, frailty emerges as a state of lower function of the whole organism, and the association is nonlinear; and that there is a point of no return beyond which function at a lower state is no longer compatible with life.

A healthy organism is composed of modular systems whose function is abnormal when people are physically frail

A healthy organism is composed of systems, or modules, with largely independent functions. The function of most systems deteriorates with age17,18. Among the full panoply, there is a core set of systems and subsystems that are critical for managing homeostasis and which have also been shown to function at abnormal levels when people are physically frail20. These systems include the metabolic, musculoskeletal and stress-response systems (Fig. 1). We summarize briefly here evidence of these associations.

Physical frailty prevalence and incidence have been linked to altered energy metabolism through both metabolic systems, including glucose–insulin dynamics21, glucose intolerance22, insulin resistance23 and alterations in energy-regulatory hormones such as leptin, ghrelin and adiponectin24,25,26,27, and alterations in musculoskeletal system function, including the efficiency of energy utilization28 and mitochondrial energy production and mitochondrial copy number29,30. Notably, across these systems, both energy production and utilization are abnormal in those who are physically frail.

The aggregate stress-response system and its subsystems are also abnormal in physical frailty. Specifically, inflammation is consistently associated with being frail, including significant associations with elevated levels of inflammatory mediators such as C-reactive protein, interleukin (IL)-6 and white blood cells including macrophages and neutrophils, among others31,32,33,34,35, in a broad pattern of chronic, low-grade inflammation36,37,38,39. Indicators of autonomic nervous system dysregulation in frailty include diminished second-to-second heart rate variability40,41,42 and compromised orthostatic43 and cardiac44 control. Physical frailty is also associated with dysregulation of functions of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, including higher levels and blunted diurnal variation of salivary cortisol45,46 and lower levels of the adrenal androgen DHEAS47,48. Together, these studies characterize frail individuals as less able to finely tune responses to environmental variation. While the systems identified here are neither definitive nor exclusive, they likely form a hub of dominant pathophysiological characteristics in the physically frail.

Experimental evidence of impaired physiological responsiveness of key systems in the frail

The abnormal levels of biomarkers in the three systems above is notable but does not offer formal evidence of the clinical vulnerability to stressors in frail older adults. Complex systems theory predicts that compromised dynamical functioning of systems may not be apparent in a resting or non-stressed state but emerges clearly under conditions of stress or the need to adapt. Stimulus–response experiments provide a particularly compelling method to elucidate and characterize response under conditions of stress49.

We summarize here five experiments exposing community-dwelling older adults to minor physiological stressors in the systems described above (Fig. 1) and the resulting physiological responses in phenotypically nonfrail, prefrail and frail individuals. Although the first four experiments represent pilot research, taken together, the parallelism of the stress–response findings is notable (Fig. 2) and suggestive of an ensemble role. The first three were conducted in a single cohort of women 85–94 years of age participating in substudies of the Women’s Health and Aging Study (WHAS) II.

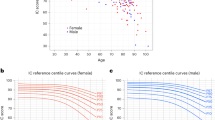

Pilot studies in a–c were conducted in community-dwelling women 85–94 years of age in WHAS II. The study in d was of male and female volunteers ages 70 and older, including WHAS II participants. a, Glucose (left) and insulin (right) dynamics during OGTT by physical frailty status; data are shown as the mean ± standard error (s.e.; error bars) for glucose and insulin values at 0, 30, 60, 120 and 180 minutes after administration of a glucose load of 75 g by frailty status. The P values for comparisons of the area under the curve (AUC) were 0.82 (prefrail versus nonfrail) and 0.02 (frail versus nonfrail) for glucose and 0.26 (nonfrail versus prefrail) and 0.27 (nonfrail versus frail) for insulin33. Panel reproduced from ref. 21. b, Time to 95% recovery of PCr levels after mild exercise, calculated as 3/k, where k is the rate constant of the monoexponential fit. The P values for comparisons of the group means in this pilot were 0.57 (prefrail versus nonfrail) and 0.22 (frail versus nonfrail), likely owing to the sample size of 30 (ref. 50). Panel reproduced from ref. 50. c, DHEA response to ACTH stimulation test by frailty status. Data are shown as the mean ± s.e. (error bars) for DHEA values at 0, 30, 60 and 120 minutes after administration of 250 μg ACTH. The P value for a global test of difference in mean by frailty status was 0.86 (ref. 63) in this pilot study of 51 women. Panel reproduced from ref. 52. d, Response to influenza vaccination in people 70 years and older; data are shown as the geometric mean HI antibody titer (GMT) ratios to H1N1, H3N2 and B strains in all study participants and by frailty status (left) and the rate of ILI and laboratory-confirmed influenza infection (right) during the post-vaccination season. The P values for the GMT ratios (0.04, 0.01 and 0.05 for H1N1, H3N2 and B strains, respectively) were obtained from linear regression for a stepwise trend of decrease from nonfrail to prefrail to physically frail individuals, adjusted for age; the corresponding P values for ILI (0.005) and influenza infection (0.03) rates were obtained from logistic regression analysis for a stepwise trend of increase from nonfrail to prefrail to frail individuals, adjusted for age53. Panel reproduced from ref. 53. Physical frailty criteria: 0, nonfrail; 1–2, prefrail; 3–5, frail1.

Metabolic system and glucose metabolism

Women without diabetes were administered a standard oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT; n = 73) (Fig. 2a). There was little distinction in mean baseline glucose or insulin levels by frailty status. Following stress challenge, physically frail women showed an exaggerated rise in both measures, together with prolonged responses, in comparison to prefrail and nonfrail women, when adjusting for age21. Overall, the mean peak glucose level was increased by more than 30% in the frail group versus the other two groups, and the mean peak insulin level was increased by 75%. Further, there was a dysregulated response of the appetite-stimulating hormone ghrelin in the OGTT, with physically frail women maintaining lower levels throughout the 2-hour experiment in comparison to nonfrail women24. Notably, only 27% of all study participants had a normal fasting glucose level (<100 mg dl–1), whereas 48% had prediabetes (2-hour glucose <140 mg dl–1) and 25% had undiagnosed diabetes. Dysregulation of glucose appeared to be the norm among these women, but the response to challenge was markedly more dysregulated among the frail subset.

Skeletal muscle system

Women (n = 30) engaged in isometric exercise of the dominant lower extremity for 30 seconds within a magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging unit (Fig. 2b). Oxidative phosphorylation in buffering ATP levels in skeletal muscle was assessed: the phosphocreatine (PCr) recovery kinetics were slower among frail women (189 ± 20 seconds) than among prefrail (152 ± 23 seconds) and nonfrail (132 ± 32 seconds) women50. Thus, the frail and prefrail groups had PCr recovery that was 57 and 20 seconds slower, respectively, than for the nonfrail group. A recently published study shows rapid energetic decline in the exercised skeletal muscle of frail compared to nonfrail older adults, further demonstrating stress-induced energy dysfunction in frailty51.

Stress-response system, HPA axis

A standard adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test with 250 µg ACTH was performed in 51 women who were not taking corticosteroids (Fig. 2c). Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) responses were examined at 0, 30, 60 and 120 minutes after administration of ACTH. Pre- and post-ACTH stimulated DHEA levels did not differ statistically by frailty status; however, the dose–response curves suggested divergence after stimulation, with a more exaggerated DHEA response with increasing physical frailty and stepwise increased dysregulation across nonfrail, prefrail and frail individuals, in line with progressively inadequate negative feedback52.

Stress-response system, innate immune system and active immunity

In male and female volunteers aged 70 years and older (n = 71, including some individuals from WHAS II), frailty was associated with significantly impaired response to trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, as measured by vaccine-induced strain-specific hemagglutinin-inactivating (HI) antibody titers, when adjusting for age (Fig. 2d). Rates of influenza-like illness (ILI) and laboratory-confirmed influenza infection showed stepwise increases from nonfrail to prefrail to physically frail individuals53. Thus, frailty status may identify those less likely to respond to influenza vaccination and at higher risk of seasonal influenza and its complications despite vaccination.

Stress-response system, autonomic nervous system function

Irish participants aged 60 years and older (n = 442) underwent a lying-to-standing orthostatic blood pressure (BP) test with concurrent BP monitoring by finger cuff. Physical frailty prevalence was enriched among those experiencing orthostatic hypotension (initial criterion) in response to the test (14.1% versus 5.4% for nonfrail individuals)54.

Accordingly, both the static (see above) and dynamic response capacity of parallel physiological systems have been linked to physical frailty, with systems that may appear normal in steady state demonstrating dysregulation when challenged. These findings support the concept of physical frailty as a state characterized by compromised responsiveness to stress or stimulus in affected systems (Fig. 3). This is consistent with complex systems theory and also may contribute to understanding of the high aging-related vulnerability of some older adults to stressors such as COVID-19 infection.

The physiological integrity of the system is defined by the capacity to maintain a healthy equilibrium in the face of stressors. The rolling ball represents stress-response dynamics. The level of physiological integrity is theorized to be a function of the reserves represented by both the depth of each bowl and the radius of the curvature, with greater depth and curvature representing greater reserve and resilience to stressors. Time to recovery after a stressor is a measure of this resilience (for example, see Fig. 2a for glucose recovery curves in the OGTT showing that frail older adults have a much slower time to recovery). Both episodic (for example, stroke, fall) and chronic (for example, chronic inflammation) insults are hypothesized to decrease the integrity of the system, thus degrading the ability to return to equilibrium and to respond to subsequent stressors. Progression of frailty consists of a series of critical transitions (denoted by asterisks) between states of equilibrium of decreasing integrity; at a particular critical transition point, the system becomes overwhelmed and can no longer harness the resources needed to maintain integrity, resulting in the clinical phenotype of physical frailty. Reproduced from ref. 7.

Weakened interactions and feedback between systems underpinning physiological vulnerability of frailty

A notable aspect of the three physiological systems dominantly dysregulated in physical frailty is that their functions interact with those of the other systems in feedforward or feedback effects55,56,57. A healthy state involves the systems in Fig. 1 interacting with each other optimally58,59,60,61,62. For example, immune system-generated cytokines drive a robust response to an infection through inflammatory cytokines and shut that same response down through anti-inflammatory cytokines63. However, if the inflammatory signaling continues chronically, in a feedforward way, as is observed in physical frailty, it impacts other systems and tissues with results including altered HPA axis activity and energy metabolism by promotion of insulin resistance and glucose intolerance as well as decreased mitochondrial energy production, altered red blood cell formation and skeletal muscle decline58,64,65. Both inflammatory signaling and skeletal muscle inactivity amplify cortisol, the product of the HPA axis, to more rapidly catabolize skeletal muscle. Cortisol normally tamps down inflammatory signaling66. However, in the face of chronicity and lowered ability to block inflammatory signaling, cortisol can impact energy metabolism via insulin resistance64,66,67. These examples offer support for dysregulation of the feedback loops between core systems associated with the physically frail state and for the networked nature of physiological dysregulation, in line with a complex dynamical system (Boxes 1 and 2). These observations also support dysregulated communication and information processing as a core feature of physical frailty.

There is further evidence that feedback relationships among these systems are altered as a consequence of cumulative stress over the life course, called allostatic load, compromising the ability of the integrated physiological systems to adapt, termed allostasis57. Physical frailty may be a more severe state of allostatic compromise68,69, propelled by aging processes as well as stressors. However, we should be cautious in interpreting the dysregulated links between systems as automatically implying a cascade of dysregulation. Contrary to the widespread assumption that aging is a purely detrimental process, there are many aspects of aging—notably, much of immunosenescence—that represent adaptations either to other detrimental processes or to changing needs at different ages70,71. This raises the speculation that the frail state might itself be adaptive, a way of staving off death or overt disease states.

Evidence for nonlinearity in the relationship between the number of dysregulated systems and frailty

The dynamics of complex systems generally render them nonlinear (Box 1), where the multiple inputs act non-additively, exhibiting synergistic or antagonistic effects. If physical frailty is a state that results from a threshold level of dysregulation of the complex dynamical system of human homeostasis, the transition from a state of standard functioning to a critically dysregulated state would theoretically be expected to be nonlinear. That is, as the number of systems malfunctioning increases, the risk of frailty escalates nonlinearly.

The preliminary evidence is consistent with theory. A population-based study of women 70–80 years of age evaluated the hypotheses that dysregulation of multiple physiological systems is associated with the risk of frailty, that no single system explains this and that the strength of association accelerates in a nonlinear fashion with increasing numbers of dysregulated systems72. Assessing eight markers from different physiological systems independently related to physical frailty ((inflammation (IL-6 > 4.6 pg ml–1), anemia (hemoglobin < 12 g dl–1), the endocrine system (insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 < 74.3 µg l–1, DHEAS < 0.215 µg ml–1, hemoglobin A1C > 6.5%), micronutrient deficiencies (≥2), adiposity (triceps skinfold thickness < 17 mm) and slow fine motor speed (> 31.9 s)), physical frailty was found to be associated with an increased number of impaired system markers, independently of associations with individual biomarkers. The odds ratio for those with 1–2 abnormal systems was 4.8 (compared to those with no abnormal systems), increasing to 11- and 26-fold-increased risk, respectively, for those with 3–4 and 5 or more systems at abnormal levels (95% confidence intervals exclude 1). Comorbid diseases were associated with physical frailty, independently of the number of abnormal systems. Commensurately, there was a nonlinear increase in frailty prevalence with increasing numbers of abnormal physiological systems (Fig. 4). These findings from the WHAS I and II study72 have recently been replicated in an additional population from Quebec69.

The filled dots connected by the solid line segments are prevalence estimates corresponding to the number of dysregulated systems, based on a generalized linear model with a binomial family distribution for being frail (versus nonfrail) and identity link while treating the number of dysregulated systems as dummy variables. The vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals for the prevalence estimates. When fitting a quadratic equation to the curve, the quadratic term was statistically significant, at P = 0.027. The dashed line shows that a linear model does not fit the increase in prevalence of physical frailty. Adapted from ref. 72.

The fact that multisystem decrements, not any subgroups, were significantly associated with frailty indicates that a multiplicity of physiological abnormalities is what is of import, more than any one specific system, in physical frailty. This speaks to the diffuseness or distributed nature of the underlying process, a key prediction for an emergent property in a complex system, and offers a theoretical basis for the null findings from numerous single-hormone replacement trials73,74,75: replacing a defective part does not solve the problem of the dysregulated whole. In summary, the combination of multisystem dysregulation and nonlinearity in the relationship with physical frailty supports complex dynamical system dysregulation as a distinct pathophysiology associated with the clinical presentation.

Evidence for critical transitions in physiology and in clinical severity

Critical transitions are abrupt changes in the state of complex dynamical systems resulting from the internal dynamics of the system (Boxes 1 and 2). The above findings on nonlinearity support the hypothesis that frailty results from a critical level of dysregulation of a complex dynamical system, resulting in a critical transition to a new emergent state76,77,78, in this case one of lower function. This is consistent with prior reports that individual senescent processes display quasilinear properties of decline across the life course but their aggregate effect is nonlinear79. There are at least three potential types of critical transitions associated with physical frailty: transition to a physiologically vulnerable state, transition to a clinically apparent phenotype and transition to disability and death. Figure 3 conceptually exemplifies the sequence of critical transitions due to age-related progressive deterioration in physiological integrity that results in an impaired ability to respond to stressors and in distinct clinical states (for example, prefrail and frail states, death). The above data on stimulus–response experiments (Fig. 2) and on nonlinearity (Fig. 4) agree with this critical transition theory.

As in Fig. 3, there are critical age-related transitions in physiological integrity that underlie transitions in clinical states. Within clinical states, there is also evidence of transition dynamics. For example, there is a hierarchy in the emergence of criteria in the phenotype of physical frailty (Fig. 1), starting with muscle weakness, slowness and low physical activity; exhaustion (or fatigue) and weight loss are generally the tipping points for the onset of physical frailty80. The critical transition to physical frailty portends a compromised stress response (Fig. 2) and risk for adverse outcomes.

Finally, the evidence to date raises the question of whether the most severe manifestations of physical frailty are a critical transition point to further decline and death. The evidence is that there is a sharp escalation in risk of adverse outcomes of disability and death when individuals manifest the phenotype of physical frailty1 (Fig. 1), and meeting all five physical frailty criteria signals the beginning of a transition toward a point of no return, beyond which the process becomes irreversible and death becomes imminent81.

Potential drivers of the complex system dysregulation underlying physical frailty

The evidence that multiple systems are dysregulated in parallel in physical frailty raises the question of whether there is a shared biological driver of this parallel dysregulation and the aggregate effects. Figure 1 describes a conceptual framework in which molecular changes drive physiological changes in energy, musculoskeletal and stress-response systems. It is plausible that cellular and molecular hallmarks of aging may contribute to physical frailty, including genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, proteostasis loss, dysregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion and altered intercellular communication18. The altered dynamical physiological systems point to at least three of these hallmarks, intercellular communication, cellular senescence and mitochondrial dysfunction, as potential drivers of physical frailty. For cellular senescence, this plausibility references a common feature of physical frailty: high levels of inflammatory mediators (chronic inflammation), which are known to be heavily secreted from senescent cell types82. There is also direct evidence that cellular senescence and mitochondrial function have a role in physical frailty. Senescent cells injected into younger mice accelerate a trajectory toward physical frailty, while senolytic treatment reverses this83. Evidence of mitochondrial energy production deficits exists in both humans and a mouse model of frailty28,84. In humans, PCr recovery time, a measure of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, is reduced50,51. In a mouse model of frailty derived through chronic inflammation, skeletal muscle ATP kinetics are impaired and decreased mitochondrial degradation in skeletal muscle has been identified28,85. Finally, indirect evidence comes from studies demonstrating that mitochondrial dysfunction is highly related to glucose intolerance at a tissue level86, which is associated in humans with physical frailty21,51.

Looking through a different lens at the data already presented, there is now early evidence suggesting that aging-related energy dysregulation is an underlying driver of generalized physiological dysregulation and the emergence of a frail state. Consider that the phenotype of physical frailty is associated with compromise in cellular repletion of energy (Fig. 2b)50, with dysregulated glucose metabolism affecting energy availability, insulin resistance and glucose regulation (Fig. 2a), and with energy intake via the impact of ghrelin on appetite regulation21,24. Skeletal muscle energetic depletion and catabolite accumulation have been shown to be a determinant of fatigue, or exhaustion, a hallmark manifestation of physical frailty1,20,87, and sarcopenia is associated with decreased efficiency of muscular energy utilization28,88. Additionally, frail older adults exhibit dysregulation of the resting metabolic rate, with greater variance than those who are not frail or prefrail89. Further, in a recent study in frail mice, cellular energetics involving mitochondrial energy production and oxidative stress were found to be central to the stress response28,90. Mitochondrial dysfunctions were shown to alter the HPA axis, sympathetic adrenal–medullary activation and catecholamine levels, the inflammatory cytokine IL-6, circulating metabolites and hippocampal gene expression responses to stress91. In older adults, there are also strong associations of altered mitochondrial function and gene expression with physical frailty29,30. Finally, the a priori hypothesis about the phenotype of frailty itself was that the five criteria for frailty constituted a set of markers connected in a vicious cycle of apparent dysregulated energetics1,92.

On the basis of this evidence, we hypothesize that not only do energetics underlie the healthy functioning of the human organism but energetic imbalance is a key driver of physical frailty—and of the clinical vicious cycle of the phenotype of frailty and its adverse outcomes (Fig. 1). Living organisms can be viewed as thermodynamic machines efficiently exchanging energy with their environment. Eventually, the energy exchange and utilization become critically suboptimal, owing to aging, stress and disuse. The less the energy flows through the system (due to decreased activity), the greater the discord between structure and function, as well as between the organism and its environment. With energetic imbalance, the system shrinks and is driven to a frail state, with a severely compromised ability to withstand stressors.

Notably, if energy can explain the simultaneous and parallel dysregulations and diminished interactions within and between systems, physical activity could be considered as a model intervention to prevent the frayed complex dynamical system underlying frailty93, as it upregulates all related systems and increases the energy flow through the ‘entire’ organism, making the thermodynamics of life favorable for thriving. Walter Bortz puts this beautifully: “every cell, every organ, every system of the body is beholden to the energetic imperative. We become what we do. Frailty is what happens when we don’t”94.

Discussion

We have summarized the above evidence supporting the thesis that physical frailty arises from critical dysregulation of a complex dynamical system, whose primary components are highlighted in Fig. 1, and that it is the outcome of a critical transition to a distinct state of suboptimal functioning and high risk when stressed. This framework changes the search for successful prevention or treatment. First, critical transitions necessitate early action, before the transition is imminent. Second, this approach can explain why replenishment of a single-system deficit has not been fruitful in frailty prevention and treatment of frailty (which may require, instead, to be most effective) interventions to tune and optimize physiology as a whole. Aggregate multisystem fitness to maintain homeostasis and resilience and to prevent physical frailty likely requires macro-level interventions that are non-reductionist—for example, interventions to improve physical activity or social engagement; the latter, apart from contributing to psychological well-being, also can increase physical and cognitive activity95,96,97. Physical activity improves function at every level of Fig. 1, including the elements of the phenotype and each of the core systems in the hub of physiological frailty, and upregulates mitochondrial function, simultaneously modulating multiple interconnected regulatory systems93. There is strong evidence that frailty is both prevented and ameliorated by physical activity, with or without a Mediterranean diet or increased protein intake98,99,100,101. These model interventions to date are nonpharmacological, behavioral ones, emphasizing the potential for prevention through a complex systems approach.

Two other major types of intervention are used to ameliorate frailty: individually tailored geriatric care models and pharmacological interventions. Individually tailored multicomponent geriatric care models prescribe interventions based on a patient’s specific impairments. The results so far have been mixed87,102. Pharmacological interventions, on the other hand, have been focused on single systems with two primary targets: inflammation and anabolic hormones. There is no direct evidence of efficacy of pharmacological interventions on physical frailty beyond phenotypic components such as muscle strength, body weight and fatigue103. Interventions designed to target the phenotypic components of frailty or a single-system-focused one deficit/one therapy model in the case of hormonal therapy will likely be ineffective in alleviating the root cause(s) of frailty104,105. Rather, pharmacology to improve multiple systems simultaneously and/or individually tailored pharmacology via precision medicine to personalize how equilibrium is restored may be required. Until that time, direct clinical intervention needs to better manage frail older adults through minimizing aggravating factors such as polypharmacy, environmental hazards (for example, fall prevention) and discontinuities of care while optimizing health- and resilience-producing behaviors such as physical activity. For all potential frailty and functional performance assessments, it is critically important to assess these outcome measures in both observational and interventional clinical trials.

More broadly, understanding frailty as the outcome of both life course stressors resulting in allostatic load57 and age-related dysregulation of our complex dynamical symphony could offer a paradigm shift in thinking. The concepts in Fig. 3 may offer a way to work in reverse to understand the fabric of health and robustness and, then, forward to understand how the fraying of this fabric is initially compensated by resilience but progression results in transition to a state of frailty. Conceptualizing frailty—and health—as arising from our intertwined dynamical physiology is a prototypically gerontological approach, taking a holistic view of the well-being of older adults and using a wide arsenal to promote physical, mental and emotional health, meaning and quality of life. The existing work is still early, however. We briefly indicate here the research needs deriving from this framework.

Furthering the current evidence

The evidence on stress-response experiments cited above largely resulted from pilot studies. Confirmatory studies are needed that elicit responses in multiple systems within individuals and implement finer repeated measurement of response curves over longer recovery times, with a sufficient number of participants to allow the parameters governing fitness and interactions of the physiological ensemble to be related to frailty. Studies of multisystem dynamics could then probe the incremental effects of combined dysregulations, characterizing the physiotype and phenotype of physical frailty that jointly make up the clinical syndrome.

Further, longitudinal research is needed to elucidate the implications of changes in physiological fitness for frailty incidence and progression—particularly addressing multisystem function. The evidence for nonlinearity reported above is intriguing but not definitive. Studies are needed that deliberately elicit measures in the collection of physiological systems and subsystems that have been most strongly implicated in frailty (as opposed to using available measures in an existing study) and that do so in sufficient breadth and depth that critical inflections in the relationship of dysregulation burden with frailty risk can be detected.

High-priority research frontiers

Assuming accomplishment of the next-stage goals described above, can we determine whether there is a specific biological driver of the multisystem physiological dysregulation of physical frailty that could be targeted with prevention or treatment strategies? Given evidence already developed, energy metabolism and/or dysregulated activation of the innate immune system require further study. Second, development of frailty-related physiological measures that better predict impending critical transitions, including to prefrailty, may accelerate the creation of effective primary and secondary prevention, as well as treatment, strategies. Third, research is needed to better distinguish physical frailty and chronic disease. The likelihood that these coexist is high, as, even if not etiologically related, both increase in prevalence with age. Further, some chronic diseases such as congestive heart failure may have features of fatigue, weakness and low activity, thus resembling physical frailty phenotypic criteria. The term ‘secondary frailty’ has been used to describe such an overlapping phenotype, in contrast to ‘primary frailty’, which denotes a unique age-related clinical entity with a distinct pathophysiology106. Such secondary frailty appears to be a consequence of catabolic chronic diseases107. Future studies of frailty in persons with disease need to demonstrate that differences in function and risk between frail and nonfrail individuals do not merely reflect the severity of disease-specific pathology. It may be, then, that continued refinement of the clinical phenotype to distinguish it clearly from signs and symptoms of other specific diseases will be needed. Further, in the case of secondary frailty, it remains to be determined whether interventions targeting physical frailty-related multisystem dysregulation are more or less effective than treatment of disease-specific etiology. Finally, intervention strategies to create health in aging and prevent frailty could well build on concepts of compromised homeostasis, robustness and resiliency, as well as physical frailty, to contribute to the development of a more unified theory of aging and health. We hypothesize that robustness, resilience and frailty reflect different points on a continuum of physiological fitness and reserve—robustness to the effects of moderate stressors, typically seen in healthy younger adults; resilience, or a temporary impairment followed by recovery, seen in less healthy younger adults and healthier older adults; and frailty, seen in older adults whose physiological fitness and reserve have been depleted past a critical threshold, leaving them vulnerable to sustained adverse outcomes. This suggests an ordering: frailty implies lack of resilience and robustness; conversely, robustness implies resilience and nonfrailty. This theory as to a continuum remains to be demonstrated.

The findings presented here may have implications beyond frailty, suggesting that an architecture of aging can be developed using the blueprint of complex systems. This enterprise would be analogous to that of the Santa Fe Institute and its network of researchers who have been pursuing a revolution in science based on complex systems thinking108. We believe that such an approach may ultimately unify a multitude of aging concepts including frailty, homeostenosis and allostasis together with robustness, resilience and health, as well as reveal novel insights, suggest new avenues for research and launch a paradigm shift for the optimization of health.

References

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M146–M157 (2001).

Bandeen-Roche, K. et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the Women’s Health and Aging Studies. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61, 262–266 (2006).

Mitnitski, A. B. et al. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. Sci. World J. 1, 323–336 (2001).

Rockwood, K. & Mitnitski, A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 62, 722–727 (2007).

Xue, Q. L. et al. Discrepancy in frailty identification: move beyond predictive validity. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 387–393 (2019).

Kelaiditi, E. et al. Cognitive frailty: rational and definition from an (I.A.N.A./I.A.G.G.) international consensus group. J. Nutr. Health Aging 17, 726–734 (2013).

Xue, Q. L., Buta, B., Ma, L. N., Ge, M. L. & Carlson, M. C. Integrating frailty and cognitive phenotypes: why, how, now what? Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 8, 97–106 (2019).

Bilotta, C. et al. Frailty syndrome diagnosed according to the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures criteria and mortality in older outpatients suffering from Alzheimer’s disease: a one-year prospective cohort study. Aging Ment. Health 16, 273–280 (2012).

Collard, R. M., Boter, H., Schoevers, R. A. & Oude Voshaar, R. C. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 60, 1487–1492 (2012).

Siriwardhana, D. D., Hardoon, S., Rait, G., Weerasinghe, M. C. & Walters, K. R. Prevalence of frailty and prefrailty among community-dwelling older adults in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 8, e018195 (2018).

Llibre Rodriguez, J. J. et al. The prevalence and correlates of frailty in urban and rural populations in Latin America, China, and India: a 10/66 population-based survey. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 19, 287–295 (2018).

Boyd, C. M., Xue, Q. L., Simpson, C. F., Guralnik, J. M. & Fried, L. P. Frailty, hospitalization, and progression of disability in a cohort of disabled older women. Am. J. Med. 118, 1225–1231 (2005).

Makary, M. A. et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 210, 901–908 (2010).

Bandeen-Roche, K. et al. Principles and issues for physical frailty measurement and its clinical application. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 1107–1112 (2020).

Walston, J. et al. Moving frailty toward clinical practice: NIA intramural frailty science symposium summary. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67, 1559–1564 (2019).

Fried, L. P., Ferrucci, L., Darer, J., Williamson, J. D. & Anderson, G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 59, 255–263 (2004).

Shimokata, H. et al. Age as independent determinant of glucose tolerance. Diabetes 40, 44–51 (1991).

Lopez-Otin, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M. & Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194–1217 (2013).

Simon, H. A. The architecture of complexity. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 106, 467–482 (1962).

Li, Q. et al. Homeostatic dysregulation proceeds in parallel in multiple physiological systems. Aging Cell 14, 1103–1112 (2015).

Kalyani, R. R., Varadhan, R., Weiss, C. O., Fried, L. P. & Cappola, A. R. Frailty status and altered glucose–insulin dynamics. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 67, 1300–1306 (2012).

Blaum, C. S. et al. Is hyperglycemia associated with frailty status in older women? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57, 840–847 (2009).

Perez-Tasigchana, R. F. et al. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance are associated with frailty in older adults: a prospective cohort study. Age Ageing 46, 807–812 (2017).

Kalyani, R. R., Varadhan, R., Weiss, C. O., Fried, L. P. & Cappola, A. R. Frailty status and altered dynamics of circulating energy metabolism hormones after oral glucose in older women. J. Nutr. Health Aging 16, 679–686 (2012).

Serra-Prat, M., Palomera, E., Clave, P. & Puig-Domingo, M. Effect of age and frailty on ghrelin and cholecystokinin responses to a meal test. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89, 1410–1417 (2009).

Lana, A., Valdés-Bécares, A., Buño, A., Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. & Lopez-Garcia, E. Serum leptin concentration is associated with incident frailty in older adults. Aging Dis. 8, 240–249 (2017).

Ma, L., Sha, G., Zhang, Y. & Li, Y. Elevated serum IL-6 and adiponectin levels are associated with frailty and physical function in Chinese older adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 13, 2013–2020 (2018).

Akki, A. et al. Skeletal muscle ATP kinetics are impaired in frail mice. Age 36, 21–30 (2014).

Ashar, F. N. et al. Association of mitochondrial DNA levels with frailty and all-cause mortality. J. Mol. Med. 93, 177–186 (2015).

Moore, A. Z. et al. Polymorphisms in the mitochondrial DNA control region and frailty in older adults. PLoS ONE 5, e11069 (2010).

Van Epps, P. et al. Frailty has a stronger association with inflammation than age in older veterans. Immun. Ageing 13, 27 (2016).

Bektas, A., Schurman, S. H., Sen, R. & Ferrucci, L. Aging, inflammation and the environment. Exp. Gerontol. 105, 10–18 (2018).

Leng, S. X., Xue, Q.-L., Tian, J., Walston, J. D. & Fried, L. P. Inflammation and frailty in older women. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 55, 864–871 (2007).

Walston, J. et al. Frailty and activation of the inflammation and coagulation systems with and without clinical comorbidities: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 162, 2333–2341 (2002).

Laudisio, A. et al. The association of olfactory dysfunction, frailty, and mortality is mediated by inflammation: results from the InCHIANTI Study. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 3128231 (2019).

Ferrucci, L. & Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15, 505–522 (2018).

Bandeen-Roche, K., Walston, J. D., Huang, Y., Semba, R. D. & Ferrucci, L. Measuring systemic inflammatory regulation in older adults: evidence and utility. Rejuvenation Res. 12, 403–410 (2009).

Morrisette-Thomas, V. et al. Inflamm-aging does not simply reflect increases in pro-inflammatory markers. Mech. Ageing Dev. 139, 49–57 (2014).

Soysal, P. et al. Inflammation and frailty in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 31, 1–8 (2016).

Varadhan, R. et al. Frailty and impaired cardiac autonomic control: new insights from principal components aggregation of traditional heart rate variability indices. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 64, 682–687 (2009).

Chaves, P. H. M. et al. Physiological complexity underlying heart rate dynamics and frailty status in community-dwelling older women. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 56, 1698–1703 (2008).

Lipsitz, L. A. & Goldberger, A. L. Loss of ‘complexity’ and aging: potential applications of fractals and chaos theory to senescence. JAMA 267, 1806–1809 (1992).

Romero-Ortuno, R., Cogan, L., Foran, T., Kenny, R. A. & Fan, C. W. Continuous noninvasive orthostatic blood pressure measurements and their relationship with orthostatic intolerance, falls, and frailty in older people. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 59, 655–665 (2011).

Parvaneh, S. et al. Regulation of cardiac autonomic nervous system control across frailty statuses: a systematic review. Gerontology 62, 3–15 (2015).

Johar, H. et al. Blunted diurnal cortisol pattern is associated with frailty: a cross-sectional study of 745 participants aged 65 to 90 years. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, E464–E468 (2014).

Varadhan, R. et al. Higher levels and blunted diurnal variation of cortisol in frail older women. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 63, 190–195 (2008).

Voznesensky, M., Walsh, S., Dauser, D., Brindisi, J. & Kenny, A. M. The association between dehydroepiandosterone and frailty in older men and women. Age Ageing 38, 401–406 (2009).

Leng, S. X. et al. Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), and their relationships with serum interleukin-6, in the geriatric syndrome of frailty. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 16, 153–157 (2004).

Varadhan, R., Seplaki, C. L., Xue, Q. L., Bandeen-Roche, K. & Fried, L. P. Stimulus–response paradigm for characterizing the loss of resilience in homeostatic regulation associated with frailty. Mech. Ageing Dev. 129, 666–670 (2008).

Varadhan, R. et al. Relationship of physical frailty to phosphocreatine recovery in muscle after mild exercise stress in the oldest-old women. J. Frailty Aging 8, 162–168 (2019).

Lewsey, S. C. et al. Exercise intolerance and rapid skeletal muscle energetic decline in human age-associated frailty. JCI Insight 5, e141246 (2020).

Le, N. P., Varadhan, R., Fried, L. P. & Cappola, A. R. Cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone response to adrenocorticotropic hormone and frailty in older women. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa134 (2020).

Yao, X. et al. Frailty is associated with impairment of vaccine-induced antibody response and increase in post-vaccination influenza infection in community-dwelling older adults. Vaccine 29, 5015–5021 (2011).

Wieling, W., Krediet, C. T. P., Van Dijk, N., Linzer, M. & Tschakovsky, M. E. Initial orthostatic hypotension: review of a forgotten condition. Clin. Sci. 112, 157–165 (2007).

Kim, K. & Choe, H. K. Role of hypothalamus in aging and its underlying cellular mechanisms. Mech. Ageing Dev. 177, 74–79 (2019).

Nijhout, H. F., Sadre-Marandi, F., Best, J. & Reed, M. C. Systems biology of phenotypic robustness and plasticity. Integr. Comp. Biol. 57, 171–184 (2017).

McEwen, B. S. Stress, adaptation, and disease: allostasis and allostatic load. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 840, 33–44 (1998).

Bellavance, M. A. & Rivest, S. The HPA–immune axis and the immunomodulatory actions of glucocorticoids in the brain. Front. Immunol. 3, 136 (2014).

Ménard, C., Pfau, M. L., Hodes, G. E. & Russo, S. J. Immune and neuroendocrine mechanisms of stress vulnerability and resilience. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 62–80 (2017).

Braun, T. P. & Marks, D. L. The regulation of muscle mass by endogenous glucocorticoids. Front. Physiol. 6, 12 (2015).

Pedersen, B. K., Steensberg, A. & Schjerling, P. Exercise and interleukin-6. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 8, 137–141 (2001).

Nance, D. M. & Sanders, V. M. Autonomic innervation and regulation of the immune system (1987–2007). Brain Behav. Immun. 21, 736–745 (2007).

Kobayashi, K. S. & Flavell, R. A. Shielding the double-edged sword: negative regulation of the innate immune system. J. Leukocyte Biol. 75, 428–433 (2004).

Epstein, F. H. & Reichlin, S. Neuroendocrine–immune interactions. N. Engl. J. Med. 329, 1246–1253 (1993).

Richards, C. D. Innate immune cytokines, fibroblast phenotypes, and regulation of extracellular matrix in lung. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 37, 52–61 (2017).

Straub, R. H. Interaction of the endocrine system with inflammation: a function of energy and volume regulation. Arthritis Res. Ther. 16, 203 (2014).

Galoyan, A. Neurochemistry of brain neuroendocrine immune system: signal molecules. Neurochem. Res. 25, 1343–1355 (2000).

Szanton, S. L., Allen, J. K., Seplaki, C. L., Bandeen-Roche, K. & Fried, L. P. Allostatic load and frailty in the Women’s Health and Aging Studies. Biol. Res. Nurs. 10, 248–256 (2009).

Ghachem, A. et al. Evidence from two cohorts for the frailty syndrome as an emergent state of parallel dysregulation in multiple physiological systems. Biogerontology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-020-09903-w (2020).

Le Couteur, D. G. & Simpson, S. J. Adaptive senectitude: the prolongevity effects of aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 66A, 179–182 (2011).

Fulop, T. et al. Immunosenescence and inflamm-aging as two sides of the same coin: friends or foes? Front. Immunol. 8, 1960 (2018).

Fried, L. P. et al. Nonlinear multisystem physiological dysregulation associated with frailty in older women: implications for etiology and treatment. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 64, 1049–1057 (2009).

Kenny, A. M. et al. Effects of transdermal testosterone on bone and muscle in older men with low bioavailable testosterone levels, low bone mass, and physical frailty. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 58, 1134–1143 (2010).

Muller, M., van den Beld, A. W., van der Schouw, Y. T., Grobbee, D. E. & Lamberts, S. W. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone and atamestane supplementation on frailty in elderly men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91, 3988–3991 (2006).

Nelson, H. D., Walker, M., Zakher, B. & Mitchell, J. Menopausal hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions: a systematic review to update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. Ann. Intern. Med. 157, 104–113 (2012).

Scheffer, M. et al. Early-warning signals for critical transitions. Nature 461, 53–59 (2009).

Nakazato, Y. et al. Estimation of homeostatic dysregulation and frailty using biomarker variability: a principal component analysis of hemodialysis patients. Sci. Rep. 10, 10314 (2020).

Gijzel, S. M. et al. Dynamical resilience indicators in time series of self-rated health correspond to frailty levels in older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 72, 991–996 (2017).

Yates, F. E. Complexity of a human being: changes with age. Neurobiol. Aging 23, 17–19 (2002).

Xue, Q. L., Bandeen-Roche, K., Varadhan, R., Zhou, J. & Fried, L. P. Initial manifestations of frailty criteria and the development of frailty phenotype in the Women’s Health and Aging Study II. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 63, 984–990 (2008).

Xue, Q. L., Bandeen-Roche, K., Tian, J., Kasper, J. D. & Fried, L. P. Progression of physical frailty and the risk of all-cause mortality: is there a point of no return? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16976 (2020).

Kirkland, J. L. & Tchkonia, T. Cellular senescence: a translational perspective. EBioMedicine 21, 21–28 (2017).

Xu, M. et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med. 24, 1246–1256 (2018).

Andreux, P. A. et al. Mitochondrial function is impaired in the skeletal muscle of pre-frail elderly. Sci. Rep. 8, 8548 (2018).

Ko, F. et al. Impaired mitochondrial degradation by autophagy in the skeletal muscle of the aged female interleukin 10 null mouse. Exp. Gerontol. 73, 23–27 (2016).

Kim, J. A., Wei, Y. & Sowers, J. R. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in insulin resistance. Circ. Res. 102, 401–414 (2008).

Mazya, A. L., Garvin, P. & Ekdahl, A. W. Outpatient comprehensive geriatric assessment: effects on frailty and mortality in old people with multimorbidity and high health care utilization. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 31, 519–525 (2019).

Allen, D. G., Lamb, G. D. & Westerblad, H. Skeletal muscle fatigue: cellular mechanisms. Physiol. Rev. 88, 287–332 (2008).

Weiss, C. O., Cappola, A. R., Varadhan, R. & Fried, L. P. Resting metabolic rate in old-old women with and without frailty: variability and estimation of energy requirements. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 60, 1695–1700 (2012).

Sahin, E. et al. Telomere dysfunction induces metabolic and mitochondrial compromise. Nature 470, 359–365 (2011).

Picard, M. et al. Mitochondrial functions modulate neuroendocrine, metabolic, inflammatory, and transcriptional responses to acute psychological stress. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E6614–E6623 (2015).

Fried, L. P. & Walston, J. in Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology 4th edn (eds Hazzard, W. R. et al.) 1387–1402 (McGraw Hill, 1998).

Fried, L. P. Interventions for human frailty: physical activity as a model. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 6, a025916 (2016).

Bortz, W. Frailty. Mech. Ageing Dev. 129, 680 (2008).

Fried, L. P. et al. A social model for health promotion for an aging population: initial evidence on the Experience Corps model. J. Urban Health 81, 64–78 (2004).

Tan, E. J. et al. The long-term relationship between high-intensity volunteering and physical activity in older African American women. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 64, 304–311 (2009).

Carlson, M. C. et al. Evidence for neurocognitive plasticity in at-risk older adults: the Experience Corps program. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 64, 1275–1282 (2009).

Talegawkar, S. A. et al. A higher adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet is inversely associated with the development of frailty in community-dwelling elderly men and women. J. Nutr. 142, 2161–2166 (2012).

Deer, R. R. & Volpi, E. Protein intake and muscle function in older adults. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 18, 248–253 (2015).

Fiatarone, M. A. et al. Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. N. Engl. J. Med. 330, 1769–1775 (1994).

Cesari, M. et al. A physical activity intervention to treat the frailty syndrome in older persons—results from the LIFE-P study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 70, 216–222 (2015).

Li, C. M., Chen, C. Y., Li, C. Y., Wang, W. D. & Wu, S. C. The effectiveness of a comprehensive geriatric assessment intervention program for frailty in community-dwelling older people: a randomized, controlled trial. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 50, S39–S42 (2010).

Pazan, F. et al. Current evidence on the impact of medication optimization or pharmacological interventions on frailty or aspects of frailty: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-020-02951-8 (2020).

Cappola, A. R., Maggio, M. & Ferrucci, L. Is research on hormones and aging finished? No! Just started! J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 63, 696–697 (2008).

Ma, L. et al. Targeted deletion of interleukin-6 in a mouse model of chronic inflammation demonstrates opposing roles in aging: benefit and harm. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa156 (2020).

Fried, L. P. et al. From bedside to bench: research agenda for frailty. Sci. Aging Knowl. Environ. 2005, pe24 (2005).

Chang, S. S., Weiss, C. O., Xue, Q. L. & Fried, L. P. Association between inflammatory-related disease burden and frailty: results from the Women’s Health and Aging Studies (WHAS) I and II. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 54, 9–15 (2012).

Krakauer, D. C. et al. Worlds Hidden in Plain Sight: Thirty Years of Complexity Thinking at the Santa Fe Institute (Santa Fe Institute Press, 2019).

Sterling, P. Allostasis: a model of predictive regulation. Physiol. Behav. 106, 5–15 (2012).

Goldstein, J. Emergence as a construct: history and issues. Emergence 1, 49–72 (1999).

Taffet, G. E. in Geriatric Medicine: An Evidence-Based Approach (eds Cassel, C. K. et al.) 27–28 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2006).

Csete, M. E. & Doyle, J. C. Reverse engineering of biological complexity. Science 295, 1664–1669 (2002).

Strehler, B. L. & Mildvan, A. S. General theory of mortality and aging. Science 132, 14–21 (1960).

Varadhan, R., Walston, J. D. & Bandeen-Roche, K. Can a link be found between physical resilience and frailty in older adults by studying dynamical systems? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66, 1455–1458 (2018).

Kitano, H. Towards a theory of biological robustness. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3, 137 (2007).

Kitano, H. Biological robustness. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 826–837 (2004).

Kitano, H. Systems biology: a brief overview. Science 295, 1662–1664 (2002).

Goldstein, J. Emergence in complex systems. In The SAGE Handbook of Complexity and Management (eds Allen, P. et al.) 65–78 (SAGE, 2011).

Bar-Yam, Y. Dynamics of Complex Systems (Routledge, 2019).

Newmann, M., Barabasi, A. L. & Watts, D. J. The Structure and Dynamics of Networks (Princeton Univ. Press, 2006).

Holland, J. H. Complex adaptive systems. Daedalus 121, 17–30 (1992).

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this article to Dr. Richard Suzman, who consistently envisioned and enabled transformative aging research. We are grateful for support by the National Institute on Aging, including for WHAS I (N01 AG012112), WHAS II (M01 R000052), Pathogenesis of Physical Disability in Aging Women (MERIT Award, R37 AG019905) and the frailty-focused Johns Hopkins University Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30 AG021334). We thank M. A. O’Brien for her outstanding assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Aging thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fried, L.P., Cohen, A.A., Xue, QL. et al. The physical frailty syndrome as a transition from homeostatic symphony to cacophony. Nat Aging 1, 36–46 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-020-00017-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-020-00017-z

This article is cited by

-

The relationship between self-perceived fatigue, muscle endurance, and circulating markers of inflammation in participants of the Copenhagen aging and Midlife Biobank (CAMB)

European Review of Aging and Physical Activity (2024)

-

Age of onset for increased dose-adjusted serum concentrations of antidepressants and association with sex and genotype: An observational study of 34,777 individuals

European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology (2024)

-

Patient vulnerability is associated with poor prognosis following upfront hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastasis

International Journal of Clinical Oncology (2024)

-

FRAIL scale as a screening tool and a predictor of mortality in non-dialysis dependent patients

Journal of Nephrology (2024)

-

Metabolic dysfunction and the development of physical frailty: an aging war of attrition

GeroScience (2024)