Abstract

The Southern Andes are regarded as a typical subduction orogen formed by oblique plate convergence. However, there is considerable uncertainty as to how deformation is kinematically partitioned in the upper plate. Here we use analogue experiments conducted in the MultiBox (Multifunctional analogue Box) apparatus to investigate dextral transpression in the Southern Andes between 34 °S and 42 °S. We find that transpression in our models is caused mainly by two prominent fault sets; transpression zone-parallel dextral oblique-slip thrust faults and sinistral oblique-slip reverse faults. The latter of these sets may be equivalent to northwest-striking faults which were believed to be pre-Andean in origin. We also model variable crustal strength in our experiments and find that stronger crust north of 37 °S and weaker crust to the south best reproduces the observed GPS velocity field. We propose that transpression in the Southern Andes is accommodated by distributed deformation rather than localized displacements on few margin-parallel faults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

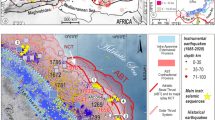

Obliquely convergent plate margins are often associated with prominent margin-parallel deformation zones in the upper plate taking up significant components of horizontal shear1,2,3. With a length of 1200 km, the Liquiñe-Ofqui Fault Zone (LOFZ) in the Southern Andean Volcanic Zone (SVZ: Fig. 1a) is such a deformation zone and one of the most prominent intra-arc deformation zones on Earth. Dextral transpression and respective strike-slip on the LOFZ is generally attributed to kinematic partitioning caused by oblique subduction of the oceanic Nazca Plate below the continental South American Plate4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. However, structural studies of the northern LOFZ identified a rather wide zone of faults with diverse orientations and kinematically associated with the LOFZ10,11,12 (Fig. 1b). These observations call into question the popular hypothesis of kinematic partitioning, by which northward displacement of the crust is accomplished on a few margin-parallel faults, notably those of the LOFZ.

a Map showing the Liquiñe-Ofqui Fault Zone (LOFZ) and the location of major volcanic centres58. b Map displaying prominent faults10,11,12, notably the Western Andean Thrust (WAT)37, contour lines of subducting slab22, and the GPS velocity field13 of the northern SVZ. The length of the plate convergence vector is not to scale.

The GPS velocity field of the Southern Andes13,14,15 portrays the current map-view displacement field of the upper crust, including the kinematics of prominent faults (Fig. 1b). GPS velocity vectors from the forearc indicate uniform and fast NE-directed displacements at a rate of 3 cm/year. South of 38 °S, vectors change from east- to southeast-directed velocities diminishing abruptly to as low as a few millimetres per year across the LOFZ. East of the magmatic arc at these latitudes, velocities continue to be low and change to westward directions. North of 38 °S, GPS velocities are directed toward the NE and diminish to less than a centimetre per year in the back-arc. The abrupt change in GPS velocity across the LOFZ at 38 °S, the northern terminus of the LOFZ, may indicate a genetic link between the velocity field and the kinematics of the LOFZ.

Co-linearity of GPS velocities in the forearc and the plate convergence vector (Fig. 1b) points to the locking of the plate interface14. These velocities have been attributed to interseismic elastic deformation14,15,16,17. However, the westward-directed displacement rates in the back-arc are often ascribed to post-seismic mantle relaxation after the Mw 9.5 1960 Valdivia earthquake13,14,15. Similarly, the directional change of GPS velocities at the LOFZ has been attributed to such relaxation at the northern portion of the Valdivia rupture zone13,16 (Fig. 1a). As mentioned before, the directional change in velocity may also be a consequence of the kinematics of the LOFZ and associated faults. Alternatively, the GPS velocity pattern may be caused by the southward decrease in upper plate crustal strength18 imparted by lithological variation or the southward decrease in crustal thickness from about 60 km at 33 °S to 40 km at 39 °S18,19,20. This crustal strength gradient may well have been enhanced by the stronger coupling of the upper plate and the shallow dipping slab18 north, in contrast to a steeper slab dip south, of the WNW-ESE striking slab tear20,21,22 (Fig. 1b).

Physical modelling allows one to explore the kinematics of oblique plate convergence. However, rather than modelling distributed deformation of transpression23,24, experimental work to date focused on the structural evolution of oblique thrusts in brittle materials, with the locations of thrusts enforced by the individual experimental setups25,26,27,28. To adequately model transpression in brittle and viscous materials, we designed the MultiBox (Multifunctional analogue Box) (Fig. 2). Here, we test to what extent the observed GPS velocity field and first-order fault zones in the SVZ are caused by kinematic partitioning associated with dextral transpression and the orogen-parallel variation in crustal strength. The experiments explore the extent to which the GPS velocity pattern of the SVZ is kinematically related to the LOFZ and changes in margin-parallel thickness, and thus strength, of crust in the upper plate. Digital image correlation allows us to calculate the model displacement vector field and to compare this field with the GPS velocity field. Our study pertains also to better understanding the significance of prominent NW-striking faults in the Southern Andes, which have been considered to be pre-Andean in origin11,29.

Results and discussion

Experimental setup

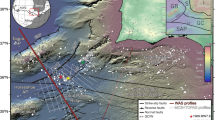

The MultiBox consists of two halves, each of which contains a piston (Fig. 2). Based on the simple shear box30, one half is mobile and moves relative to the fixed one parallel to the box midline. Computer-controlled stepper motors driving all mobile parts of the MultiBox ensure precise reproducibility of experiments. Each piston of the MultiBox is fitted with a 100 × 21 cm wooden base plate amounting to L-shapes of the pistons (Fig. 3a). The base plates and space between the plates are covered by a 3 cm thick layer of a mixture of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and fine-grained corundum31, simulating the viscous lower crust. A 0.5 cm thick layer of quartz sand with Mohr−Coulomb rheology models the brittle upper crust. The variation in crustal strength in the experiments is simulated by thickness changes of model upper crust32. An initially 27 cm wide gap between the frontal edges of both piston base plates is filled with a 0.5 cm thick layer of low-friction micro glass beads covered by plastic wrap to avoid mixing of PDMS and micro glass beads (Fig. 3a). Pilot tests indicated that the plastic wrap has no influence on the surface deformation.

a Sketch showing the general experimental setup. b Kinematic boundary conditions derived from the observed GPS velocity field and used in the experiments. The sketch of the MultiBox and the corresponding kinematics have been mirrored to represent the kinematics of deformation in nature. c Schematic diagrams showing the three experimental set-ups.

It is important to note that micro glass beads filling the gap between the pistons (Fig. 3a) mask the base plate edges and distribute deformation above, and to both sides of, the velocity discontinuity. The analogue materials are, thus, detached from the base of the MultiBox and deform freely above the gap between the pistons. During shortening, a small portion of the micro glass beads escapes below the L-shaped pistons. Therefore, the micro glass-bead layer remains nearly constant in thickness and, thus, has no influence on the overlying analogue materials in this regard. As the mobile half of the MultiBox moves left-lateral with respect to the fixed half, the graphical modelling results are mirrored to be comparable to the deformation kinematics in the SVZ. Details of the scaling, analogue materials used and quantitative image correlation are delineated in the “Methods” below.

The rate and direction of convergence in experiments are achieved by the combined movements of the L-shaped pistons and the moving box half (Fig. 3b). Collectively, these movements impart upper-crustal kinematics as inferred from the direction of plate convergence (Fig. 1b) and GPS velocities in the forearc between 35 °S and 37 °S13,15, in which material is displaced at a rate of 30.35 mm/yr toward an azimuth of 75.64° (Supplementary Table 2). Given the overall trend of the trench of N5 °E between 34 °S and 41 °S, the convergence vector in the experiments amounts to 70°. GPS data from the back-arc between 37 °S and 39 °S indicate displacement rates of about 4.11 mm/yr towards 207.76°13. Thus, the displacements in the back-arc are 7.4 times slower than in the forearc.

The experiments test different orogen-parallel crustal strength gradients by varying the thickness of the quartz sand layer of the “northern” portion of the experiment (Fig. 3c), pertaining to the region north of the slab tear (Fig. 1b). The sand thickness in the “southern” portion, modelling the region south of the slab tear (Fig. 1b), is kept constant in all experiments, i.e., 0.5 cm, and corresponds to the average upper-crustal thickness of 10 km in the SVZ and the northern LOFZ. A 15 cm wide transition zone between both portions amounts to 300 km in nature (see below). We tested three different model crustal strength setups (Fig. 3c): setup 1 is characterized by a uniform thickness of the sand layer of 0.5 cm. Setup 2 is made up of a 0.2 cm thick sand layer in the northern portion, amounting to a weaker crust there than in the southern portion. With a sand layer thickness of 0.9 cm, setup 3 models a mechanically stronger crust in the northern than in the southern portion. To assess the reproducibility of results, each experimental setup was run several times, in addition to conducting eight pilot and verification experiments (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). The results of repeated experiments proved to be similar in terms of orientation, kinematics, and overall zonation of visible faults (Supplementary Fig. 1). Differences among identical experimental setups are apparent by slight variations in fault spacing. Thus, only one experiment of each setup will be described below.

Model limitations

Our experiments do not model subduction or crustal deformation at the plate interface, i.e., bulging of material. In this regard, caution needs to be exercised in correlating model reverse faults forming close to both pistons, as such faults may arise as a consequence of contact strain. Moreover, the amount of surface uplift, notably of any bulges, does not scale properly to nature, as our experiments are not isostatically balanced and do not include erosion. Further limitations of our experimental setups include the lack of structures arising from the isostatically controlled motion of crust, notably with regard to along-strike crustal thickness variations, and from our choice of length scaling. The latter influences the spacing of structures in particular. The experiments are not meant to track the structural and kinematic evolution of specific faults, such as the LOFZ, let alone the entire duration of upper plate crustal deformation in the Southern Andes. The experiments do, however, furnish information on the formation and kinematics of first-order fault patterns and long-term displacement vector fields arising from oblique plate convergence. Finally, narrowing of transpression zones with time is an earmark of this deformation regime24 and is consistent with narrowing of the equivalent zones in our experiments (Supplementary Figs. 2–4). As the initial zone width of transpression in nature is unknown, the effect of model transpression zone narrowing on the structural evolution of crust in nature cannot be assessed at present.

Experimental results

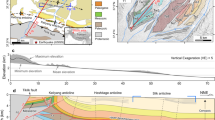

Each experiment ran for 2 h and 15 min and led to 7.87 cm of shortening in convergence direction, corresponding respectively to 5.25 Ma and 157 km in nature (Supplementary Table 1)33. Experiments of all setups show a central deformation zone bordered by an eastern and a western zone characterized by N-S-trending anticlinal surface bulges. Anastomosing reverse and strike-slip faults striking obliquely to the pistons characterize the central zone. Notably, prominent NW-striking, sinistral reverse faults are uniformly spaced in this zone and kinematically linked with higher-order faults (Fig. 4a–c). Anticlines are gentle and define zones that are largely devoid of faults and, although the formation of both started early in, and waned equally during the experiments, the western one is the more prominent one. N-S-striking reverse faults are typical for the eastern and western zones, but are more prominent in the western zone (Fig. 4a–c).

Model structures of a setup 1 experiments, b setup 2 experiments, and c setup 3 experiments. Model displacement vectors of d setup 1 experiments, e setup 2 experiments, and f setup 3 experiments. Red stippled lines indicate surface traces of profiles in Supplementary Fig. 5. TZ indicates the transition zone.

In setup 1 experiments, faults localize first in the central zone, where they are uniformly distributed (Supplementary Fig. 2). The faults display variable components of thrusting, dextral shearing, and clockwise particle rotation (Fig. 5a–c). Fault evolution tracked on an E-W profile reveals that each fault is active for approximately 60 min (Supplementary Fig. 2). Moreover, the successive onset of faults and narrowing of the central zone show that deformation propagates eastward. N-S-striking reverse and thrust faults develop uniformly over the entire length of the western zone (Fig. 4a–c). In setup 2 experiments, the northern central and western zones, underlain by the weak crust, show a large number of reverse faults. Thrusting, dextral shear, and clockwise particle rotation are maximal in the northern central zone (Fig. 5d–f). Moreover, the eastward propagation of faults is more apparent in this zone than elsewhere (Supplementary Fig. 3). A prominent NE-striking, sinistral strike-slip fault affected the southern central zone and propagated far into the eastern zone (Figs. 4b, 5f). In setup 3 experiments, a most prominent piston-parallel thrust borders the northern central zone underlain by a strong crust to the W (Figs. 4c, 5g–i). Similar to setup 1, distributed faulting, clockwise particle rotation, and eastward propagation of faults are observed in the transition zone and southern central zone (Fig. 5i and Supplementary Fig. 4).

In all experiments, the velocity vectors in the western zone correspond to the uniform motion of the respective piston towards the centre (Fig. 4d–f). The displacement magnitudes decrease gradually in the central zone toward the E, without change in displacement directions. However, vectors in the eastern zone indicate substantially lower displacement magnitudes and large directional variability. In setup 1 experiments, vectors indicate small northward displacements in the eastern zone (Fig. 4d). Similar to setup 1, vectors of setup 2 experiments show northward displacement of material in the eastern zone at low magnitudes (Fig. 4e). In setup 3 experiments, displacement vectors in the transition zone and in the southern-eastern zone shift toward the east before changing to southward directions, whereas vectors in the northern eastern zone continue to be directed toward the NE (Fig. 4f).

Localization, kinematics, and age of prominent faults

As mentioned beforehand, the co-linearity of the plate convergence direction with uniform GPS velocities throughout the forearc and far beyond the Valdivia rupture zone (Fig. 1a) indicates elastic strain build-up due to locking of the plate interface and, thus, interseismic deformation in the Southern Andes15,16,17. The trench-ward motion of crust in the back-arc (Fig. 1b), also known from other subduction zones34, is often attributed to post-seismic relaxation of crust following the 1960 earthquake but is considered to be rather long35,36. Comparison of short-term and long-term fault-slip and deformation rates shows to what extent geodetic rates of deformation relate to geologic rates. Evidence from the Southern Andes in this regard is sparse. However, recent slip rate estimates from the San Ramón Fault, a segment of the Western Andean Thrust (WAT)37 located near Santiago at 33.5 °S (Fig. 1b), indicate similar long-term and short-term slip rates38. Spatially more comprehensive evidence indicating similar geologic and geodetic slip rates comes from modelling of the high-precision GPS velocity field, based on measurements at 1981 stations, and comparison with known geological slip rates from 41 fault segments of the San Andreas Fault System, California39. This study is based on an earthquake cycle model of an upper elastic layer and a lower viscoelastic half-space, which is akin to our experimental model setup and consistent with a rheological layering of the crust in the Southern Andes11. Thus, the GPS velocity field in the Southern Andes may well portray interseismic deformation, serves as a proxy for long-term deformation, and warrants the comparison with model surface displacement patterns from analogue experiments.

The western, central, and eastern zones in our experimental setups scale respectively to the forearc, the volcanic arc, and the back-arc between 34 °S to 42 °S (Fig. 1b). Although the western anticlinal bulge developed largely as a consequence of the experimental boundary conditions, its position, and width approximate the deformation gap between the model forearc and the volcanic arc (Fig. 4). As mentioned above, the amount of surface uplift of the bulge does not scale properly to nature. Nonetheless, a thrust belt developed to the west of this bulge and corresponds to the Coastal Cordillera of the forearc in nature.

Similar to structural and kinematic field evidence from the SVZ10,11,12 and the central Andes40, all of our experiments show the formation of two prominent fault sets in the central zones: margin-parallel dextral oblique-slip thrust faults and NW-striking sinistral oblique-slip reverse faults (Figs. 4a–c, 6). In places, the model reverse faults converge downward and form pop-up structures (Supplementary Fig. 5), similar to those observed by Schreurs and Colletta (1998)41 in transpression experiments. Dextral shear components on thrust and reverse faults as well as clockwise particle rotation in the central zones (Figs. 4a–c, 5) point to dextral transpression affecting the entire width of the central zone, i.e., the model volcanic arc. The model fault sets enclose rhomb-shaped domains of diminished internal deformation, akin to those recognized in the SVZ10,11,12 and the central Andes40. Thus, field evidence10,11,12,40 and our experiments call into question the popular view that margin-parallel dextral shear in the SVZ has been exclusively resolved on the LOFZ, which emerged rather late in the orogenic history9,42.

In terms of fault localization, the presence of prominent, NW-striking faults apparent in the central zones of all experiments is of particular importance (Fig. 4). The faults are uniformly spaced and characterized by oblique sinistral reverse sense-of-shear (Figs. 4a–c, 5c, f, i). The orientation, kinematics, and spacing of the faults are comparable to prominent NW-trending discontinuities in the SVZ (Figs. 1b, 6), some of them are lined by large volcanic centres, such as the Villarrica, Quetrupillán, and Lanín, forming transverse volcanic chains. The discontinuities are often considered pre-Andean in origin11,29. In the experiments, however, these faults localized rather early and spontaneously, i.e., unrelated to any inherited mechanical heterogeneity, are long-lived and form antithetic Riedel faults with respect to overall dextral transpression. Therefore, NW-striking faults may not be pre-Andean in origin, but may have formed early during Andean deformation.

Another noteworthy structural characteristic of our experiments is the development of a first-order reverse fault bounding the central zone to the W in setups 1 and 3 (Fig. 4a, c). The fault is visible well in normal and, more prominently, in the strong model crust. Notably in the latter, the fault takes up all displacement of the central zone, leaving this zone largely unstrained (Figs. 4c, 5g–i). The position, polarity, and kinematics of the reverse fault matches remarkably well those of the WAT, one of the most important structural, mechanical and morphological discontinuities in the entire Andes37,38,43 (Figs. 1b, 6). The WAT initiated in early Miocene times, is synthetic to the plate interface megathrust and displaces rocks of the magmatic arc (Principal Cordillera) over less deformed rocks of the forearc. It can be traced from the Peruvian Andes at 17 °S to the Southern Andes43,44, where it includes the San Ramón fault37,38. Interestingly, the WAT appears to terminate at the latitude of 38 °S45, i.e., the location of the slab tear projected to the surface (Fig. 1b). As mentioned before, our experiments do not fully model the dynamics of subduction of the Southern Andes. However, the development of the model WAT, notably in experiments modelling the deformation of the strong crust, points to the importance of crustal strength in controlling crustal kinematics in the Southern Andes.

Importance of margin-parallel crustal strength gradient

The northern terminus of the LOFZ, the southern terminus of the WAT, and the GPS velocity field relate spatially to the change in slab dip at 37 °S (Fig. 1), which translates to differences in strength of upper plate crust18. The analogue experiments highlight the influence of crustal strength on the upper-crustal fault pattern and surface displacement fields. Setup 1 experiments do not entail an orogen-parallel strength difference and, thus, generate displacement vectors that are uniform along-strike, but change directions and magnitudes towards the central portion (Fig. 4d). Setup 2 experiments are characterized by a weak upper crust in the north displaying pronounced northward surface displacements in the model back-arc (Fig. 4e). Clearly, the displacement fields of these setups do not match the observed GPS velocity vectors (Fig. 1b).

Displacements in setup 3 experiments, modelling strong crust in the north, are characterized by (1) an abrupt change in magnitudes across the model WAT, serving as a distinct velocity discontinuity, (2) eastward directed displacements in the transition zone of the central zone and (3) a change from NE-directed vectors north of the transition zone to SW-directed small-magnitude vectors south of the zone in the eastern zone (Fig. 4f). Thus, the modelled displacement vector field of setup 3 portrays the GPS velocity field (Figs. 1b, 4f).

Likewise, the pattern and kinematics of setup 3 model faults agree well with that of first-order faults compiled for the SVZ (Figs. 1b, 6). Specifically, south of the transition zone, which spatially corresponds to the slab tear in nature, N-striking dextral oblique, and NW-striking sinistral oblique thrusts are well apparent in setup 3 experiments and nature (Fig. 6). North of the transition zone (i.e., slab tear), N-striking thrust faults, notably the prominent one spatially matching the WAT, characterize setup 3 experiments and are, thus, consistent with the natural fault pattern as well. E-striking faults, sporadically evident south of the slab tear, are not developed in any of the experiments. As these faults are less prominent than the N- and NW-striking faults, we attribute the lack of E-striking faults in the experiments to the length scaling, which does not allow the development of respective higher-order faults. Similarly, the length scale can explain the differences in the spacing of model faults with regard to their natural equivalents. In summary, the model crustal strength gradient of setup 3 experiments can account for the GPS velocity field, pattern, and kinematics of first-order fault zones, and change from dextral transpression in the south to thrust-dominated deformation in the north (Fig. 6).

Conclusions

Scaled analogue experiments simulating crustal transpression using the MultiBox prompt us to reconsider the simple concept of kinematic partitioning at the obliquely convergent Southern Andean plate margin between 34 °S to 42 °S. Comparison of the model velocity field inferred from 3D digital image correlation with GPS velocities supports the hypothesis that crust north of the tear in the subducted slab is stronger than south of the tear. We conclude that the entire GPS velocity field in the Southern Andes portrays long-term (interseismic) deformation. Contrary to the popular hypothesis, by which the LOFZ takes up most of the margin-parallel dextral oblique displacement, we find that transpression is accomplished chiefly by oblique-slip reverse and thrust faults, which are widely distributed across the entire width of the model orogen, in agreement with compiled first-order faults in the SVZ (Fig. 6). Specifically, two major, kinematically linked fault sets caused tectonic segmentation of model upper crust into rhomb-shaped domains. Finally, prominent, regularly spaced NW-striking faults localized spontaneously as Riedel shears early in all of our experiments. Thus, these faults are inherently related to dextral transpression and challenge the general belief that their natural equivalents generally formed from pre-Andean discontinuities. The evolution of volcanic centres decorating these faults is, therefore, unlikely related to ancient crustal discontinuities.

Methods

Scaling

Accurate scaling of experiments is a prerequisite to ensure physical comparability between models (m) and nature (n) and for extrapolating experimental results to nature. The principal constraining parameter for the scaling of laboratory experiments is the length scale. In our experiments, a model upper crustal thickness of e.g., lm = 0.5 cm corresponds to an upper crustal thickness in nature of ln = 10 km. This amounts to a length scale ratio of (Supplementary Table 3):

In order to achieve physical similarity between the models and nature, we need to derive dimensionless parameters representing the physical system of our experiment46,47. The controlling parameters in our experiments are the strength ratios between brittle and ductile materials. The dimensionless parameters have to be independent of length l = [L], mass m = [M], and time t = [T]. The major parameters influencing our experiments are length: l = L, density: ρ = M L−3, gravity: g = L T−2, velocity: u = L T−1, and dimensionless friction angle: ϕ. The brittle−ductile coupling is characterized by the empirically constrained strength ratio R48 of differential stresses between a brittle and a ductile material:

In this study, we will use this ratio to approximate the brittle-ductile coupling in the experiments with regard to the SVZ. The dimensionless differential stress for the brittle layer can be expressed as:

This equation includes the brittle material properties, such as friction angle ϕ, density ρ, and the layer thickness lbrit.

The dimensionless differential stress for the ductile layer can be expressed as:

This depends on the ductile material properties, such as viscosity η, applied rate of shortening U as well as the length of the piston L and the layer thickness lduc.

Division of both parameters of differential stress forms the dimensionless brittle−ductile strength ratio R:

Based on the choice of materials, cohesion, density, friction angle, and gravity can be taken as constants. Besides the thickness of the brittle crust, the outcome of the experiments will depend on the applied piston velocity. This gives us the option to control the strength ratio either by varying the thickness of the brittle layer or the applied strain rate on the ductile layer. A straightforward way to generate a specific along-strike crustal strength gradient is by varying the brittle layer thickness. Our experiments are based on the calculated strength ratio of Rn = 2.148 for the average SVZ crust (Supplementary Table 4). According to this value, the weak model crust with Rm = 0.35 turned out to be 84% weaker than the normal model crust. By contrast, the strong crust with Rm = 7.083 is characterized by a 224% strength increase with regard to the normal model crust. The difference in the brittle layer thickness depends also on the technical feasibility of generating respective layers.

Based on calculations of R, the layers were shortened at a constant rate of Um = 3.5 cm/h (Um = 9.72 × 10−6 m/s) for the forearc vector. As the back-arc vector is 7.38 times slower than the forearc vector, its rate amounts to 1.19 cm/h in the experiments. The rate of shortening in the model corresponds to a natural shortening rate of Un = 30 mm/a (Un = 9.512 × 10−10 m/s), constrained by GPS data (Supplementary Table 2). The applied strain rate needs to match Rm = Rn and sets the time scaling described as the relation Um = Un. The velocity scaling ratio is then given by:

The time scale ratio for the experiments is therefore given by:

Thus, 1 h in the experiment corresponds to approximately 2.333 Ma in nature.

Analogue materials

The brittle upper crust was modelled using quartz sand, which is a Mohr−Coulomb material49,50,51,52,53. We used fire-dried, well-sorted G23T quartz sand, which has an average grain size of 290 µm (100–600 µm), a cohesion of ̴20 Pa and a stable friction angle of 28.45°54,55, which we measured at the GFZ Potsdam, Germany (Supplementary Table 5). Friction and cohesion of G23T quartz sand are similar to commonly used sand in analogue modelling54,56. The densities of sand ρm = 1562 kg/m3 and upper crust in nature ρn = 2500 kg/m3 set the density scale ratio at:

A mixture of 0.965 kg polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) type KORASILON Öl G 30 M and 1 kg fine-grained corundum sand was used to model the lower crust31. This mixture was chosen for its density of ρm = 1600 kg/m3, to prevent buoyancy effects in combination with the sand (Supplementary Table 5). With regard to the average density of lower crust ρn = 2800 kg/m3, the density scale ratio is:

The stress exponent of the PDMS/corundum mixture is n = 1.05 (Supplementary Table 5). Therefore, the mixture is a Newtonian fluid with an effective viscosity of η = 1.5 × 105 Pa s. Considering a viscosity η = 1 × 1022 Pa s for the lower crustal of the Southern Andes13,16, the viscosity scale ratio is:

The micro glass beads are perfectly spherical, have very low friction and cohesion, are well sorted, range in size from 40 to 80 μm, and have a density of ρm = 1500 kg/m3. The beads serve as a low-friction material that remains at the bottom during experiments.

3D digital image correlation

The experiments were recorded with a 3D Stereo Digital Image Correlation StrainMaster system manufactured by LaVision GmbH (Germany). Two monochrome Imager M-lite 12M CMOS cameras with a 12-bit sensor (12-megapixel, 4112 × 3008 pixels, 4096 values of grey) were mounted above the model surface. The images were recorded and synchronized with a Device Control Unit X (DCU X) running DaVis 10.0.4 by LaVision GmbH. A set of high-quality Nikon lenses with 24 and 35 mm focal lengths were used. The focal length of 24 mm allowed us to capture a large area within the MultiBox, whereas using a focal length of 35 mm resulted in cropped images of the experiment surface (Fig. 3b). The experiments shown here have been recorded with a focal length of 35 mm (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 1).

Stereo DIC permits the computation of 3D surface displacements by cross-correlation of sequentially recorded stereo image pairs57. Simultaneous application of stereo image reconstruction generates a high-resolution 3D model of the surface topography. This allows us to quantify the evolution of the monitored surface. The quartz sand used for the brittle layer includes black grains serving as markers for DIC cross-correlation. The mixing ratio of 1:12 with regard to bright sand is tailored to the cameras, their distances to the surface, and the experiment size. The black marker grains have the same physical properties as bright sand. Sieving the sand creates random patterns, which improves image correlation. Calibration of the cameras prior to each experiment identified and corrected lens distortions, calculated the camera position relative to each other for stereo reconstruction, and set the correct length scale to ensure high-precision vector field calculation.

The software DaVis 10.0.4 was used to calculate the displacement vector field evolution at a resolution of a few grain size diameters by calculating the incremental and cumulative vector fields for each experiment. Based on the computed vector fields, the software furnished also important kinematic derivatives of surface deformation including: surface displacements in X-, Y- and Z-directions; vertical-axis rotation; shear strain defined as:

and divergence, with convergent particle motion, denoted as negative values, and divergent particle motion indicated as positive values:

Careful removal of the sand layer immediately after completion of each experiment revealed the deformed PDMS surface and allowed us to record this surface in 3D. Digital cross-sections at selected locations were generated by combining the shapes of the final sand surface and the excavated PDMS surface.

Data availability

The experimental data that support the findings of this study are available in GFZ data services with the identifier https://doi.org/10.5880/fidgeo.2021.023.

References

Fitch, T. J. Plate convergence, transcurrent faults, and internal deformation adjacent to Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. 77, 4432–4460 (1972).

Jarrard, R. D. Terrane motion by strike‐slip faulting of forearc slivers. Geology 14, 780–783 (1986).

McCaffrey, R. Oblique plate convergence, slip vectors, and forearc deformation. J. Geophys. Res. 97, 8905–8915 (1992).

Hervé, F. & Thiele, R. Estado de conocimiento de las megafallas en Chile y su significado tectónico. Comun. Univ. Chile 38, 67–91 (1987).

Cembrano, J. et al. Paleomagnetism of lower cretaceous rocks from east of the Liquine-Ofqui fault zone, Southern Chile: evidence of small in-situ clockwise rotations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 113, 539–551 (1992).

Cembrano, J., Hervé, F. & Lavenu, A. The Liquiñe Ofqui fault zone: a long-lived intra-arc fault system in Southern Chile. Tectonophysics 259, 55–66 (1996).

Cembrano, J., Schermer, E., Lavenu, A. & Sanhueza, A. Contrasting nature of deformation along an intra-arc shear zone, the Liquiñe-Ofqui fault zone, southern Chilean Andes. Tectonophysics 319, 129–149 (2000).

Lange, D. et al. First seismic record for intra-arc strike-slip tectonics along the Liquiñe-Ofqui fault zone at the obliquely convergent plate margin of the southern Andes. Tectonophysics 455, 14–24 (2008).

Cembrano, J. et al. Late Cenozoic transpressional ductile deformation north of the Nazca–South America–Antarctica triple junction. Tectonophysics 354, 289–314 (2002).

Hernandez-Moreno, C., Speranza, F., & Di Chiara, A. Understanding kinematics of intra-arc transcurrent deformation: paleomagnetic evidence from the Liquiñe-Ofqui fault zone (Chile, 38–41°S). Tectonics 33, 1964–1988 (2014).

Sielfeld, G., Lange, D. & Cembrano, J. Intra-arc crustal seismicity: seismotectonic implications or the Southern Andes Volcanic Zone, Chile. Tectonics 38, 552–578 (2019).

Rosenau, M., Melnick, D. & Echtler, H. Kinematic constraints on intra-arc shear and strain partitioning in the Southern Andes between 38°S and 42°S latitude. Tectonics 25, 1–16 (2006).

Moreno, M. et al. Heterogeneous plate locking in the South–Central Chile subduction zone: building up the next great earthquake. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 305, 413–424 (2011).

Hu, Y., Wang, K., He, J., Klotz, J. & Khazaradze, G. Three-dimensional viscoelastic finite element model for postseismic deformation of the great 1960 Chile earthquake. J. Geophys. Res. 109, B12403 (2004).

Klotz, J. et al. Earthquake cycle dominates contemporary crustal deformation in Central and Southern Andes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 193, 437–446 (2001).

Wang, K. et al. Crustal motion in the zone of the 1960 Chile earthquake: Detangling earthquake-cycle deformation and forearc-sliver translation. Geochem., Geophys., Geosyst. 8, 1–14 (2007).

Ruegg, J. C. et al. Interseismic strain accumulation measured by GPS in the seismic gap between Constitución and Concepción in Chile. Phys. Earth Planet. Int. 175, 78–85 (2009).

Rodriguez Piceda, C., et al Lithospheric density structure of the Southern Central Andes constrained by 3D dataintegrative gravity modelling. Int. J. Earth. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-020-01962-1 (2020).

Krawczyk, C. M., et al. in The Andes—Active Subduction Orogeny (eds Oncken. O., Chong. G., Franz. G., Giese, P., Götze, H.-J., Ramos, V. A., Strecker, M. R., & Wigger, P.) 171–192 (Springer, 2006).

Heit, B., Yuan, X., Bianchi, M., Sodoudi, F. & Kind, R. Crustal thickness estimation beneath the Southern Central Andes at 30°S and 36°S from S wave receiver function analysis. Geophys. J. Int. 174, 249–254 (2008).

Gutscher, M.-A., Spakman, W., Bijwaard, H. & Engdahl, E. R. Geodynamics of flat subduction: seismicity and tomographic constraints from the Andean margin. Tectonics 19, 814–833 (2000).

Pesicek, J. D., Engdahl, E. R., Thurber, C. H., DeShon, H. R. & Lange, D. Mantle subducting slab structure in the region of the 2010 M8.8 Maule earthquake (30–40°S), Chile. Geophys. J. Int. 191, 317–324 (2012).

Sanderson, D. J. & Marchini, W. R. D. Transpression. J. Struct. Geol. 6, 449–458 (1984).

Robin, P. Y. F. & Cruden, A. R. Strain and vorticity patterns in ideally ductile transpression zones. J. Struct. Geol. 16, 447–466 (1994).

Viola, G., Odonne, F. & Mancktelow, N. S. Analogue modelling of reverse fault reactivation in strike-slip and transpressive regimes: application to the Giudicarie fault system, Italian Eastern Alps. J. Struct. Geol. 26, 401–418 (2004).

Haq, S. S. & Davis, D. M. Mechanics of fore‐arc slivers: insights from simple analog models. Tectonics 29, TC5015 (2010).

Leever, K. A., Gabrielsen, R. H., Sokoutis, D. & Willingshofer, E. The effect of convergence angle on the kinematic evolution of strain partitioning in transpressional brittle wedges: insight from analog modeling and high‐resolution digital image analysis. Tectonics 30, TC2013 (2011).

Cooke, M. L., Toeneboehn, K. & Hatch, J. L. Onset of slip partitioning under oblique convergence within scaled physical experiments. Geosphere 16, 875–889 (2020).

Stanton-Yonge, A., Griffith, W. A., Cembrano, J., St. Julien, R. & Iturrieta, P. Tectonic role of margin-parallel and margin-transverse faults during oblique subduction in the Southern Volcanic Zone of the Andes: insights from boundary element modeling. Tectonics 35, 1990–2013 (2016).

Schrank, C. E., Boutelier, D. A. & Cruden, A. R. The analogue shear zone: from rheology to associated geometry. J. Struc. Geol. 30, 177–193 (2008).

Zwaan, F., Schreurs, G. & Adam, J. Effects of sedimentation on rift segment evolution and rift interaction in orthogonal and oblique extensional settings: insights from analogue models analysed with 4D X-ray computed tomography and digital volume correlation techniques. Global Planet. Change 171, 110–133 (2018).

Riller, U., Cruden, A. R., Boutelier, D. & Schrank, C. The causes of sinuous crustal-scale deformation patterns in hot orogens: evidence from scaled analogue experiments and the Southern Central Andes. J. Struc. Geol. 37, 65–74 (2012).

Eisermann, J. O., Göllner, P. L. & Riller, U. Experimental data on scaled analogue experiments modelling GPS velocity field variations and kinematic partitioning in the Southern Andes (34°S to 42°S). GFZ Data Services https://doi.org/10.5880/fidgeo.2021.023 (2021).

Chlieh, M. et al. Coseismic slip and afterslip of the great Mw 9.15 Sumatra–Andaman earthquake of 2004. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 97, 152–173 (2007).

Savage, J. C., Svarc, J. L. & Yu, S. B. Postseismic relaxation and transient creep. J. Geophys. Res. 110, 1–14 (2005).

Ito, T. et al. Isolating along‐strike variations in the depth extent of shallow creep and fault locking on the northern Great Sumatran Fault. J. Geophys. Res. 117, 1–16 (2012).

Armijo, R. et al. The West Andean Thrust, the San Ramón Fault, and the seismic hazard for Santiago, Chile. Tectonics 29, TC2007 (2010).

Riesner, M. et al. Kinematics of the active West Andean fold-and-thrust belt (central Chile): structure and long-term shortening rate. Tectonics 36, 287–303 (2017).

Tong, X., Smith-Konter, B. & Sandwell, D. T. Is there a discrepancy between geological and geodetic slip rates along the San Andreas Fault System? J. Geophys. Res. 119, 2518–2538 (2014).

Riller, U. & Oncken, O. Growth of the Central Andean Plateau by tectonic segmentation is controlled by the gradient in crustal shortening. J. Geol. 111, 367–384 (2003).

Schreurs, G. & Colletta, B. Analogue modelling of faulting in zones of continental transpression and transtension.Geol. Soc., London, Spec. Pub. 135, 59–79 (1998).

Astudillo-Sotomayor, L. et al. Fast Holocene slip and localized strain along the Liquiñe-Ofqui strike-slip fault system, Chile. Sci. Rep. 11, 5970 (2021).

Armijo, R., Lacassin, R., Coudurier-Curveur, A. & Carrizo, D. Coupled tectonic evolution of Andean orogeny and global climate. Earth Sci. Rev. 143, 1–35 (2015).

Victor, P., Oncken, O. & Glodny, J. Uplift of the western Altiplano plateau: evidence from the Precordillera between 20° and 21°S (Northern Chile). Tectonics 23, TC4004 (2004).

Maldonado, V., Contreras, M. & Melnick, D. A comprehensive database of active and potentially-active continental faults in Chile at 1:25,000 scale. Sci. Data 8, 20 (2021).

Hubbert, M. K. Theory of scale models as applied to the study of geologic structures. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 48, 1459–1520 (1937).

Galland, O., Holohan, E., van Wyk de Vries, B. & Burchardt, S. in Physical Geology of Shallow Magmatic Systems Dykes, Sills and Laccoliths 147–214 (Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, 2015).

Schueller, S. & Davy, P. Gravity influenced brittle-ductile deformation and growth faulting in the lithosphere during collision: results from laboratory experiments. J. Geophys. Res. 113, 1–21 (2008).

Davy, P. & Cobbold, P. Experiments on shortening of a 4-layer model of the continental lithosphere. Tectonophysics 188, 1–25 (1991).

Schellart, W. Shear test results for cohesion and friction coefficients for different granular materials: scaling implications for their usage in analogue modelling. Tectonophysics 324, 1–16 (2000).

Lohrmann, J., Kukowski, N., Adam, J. & Oncken, O. The impact of analogue material properties on the geometry, kinematics, and dynamics of convergent sand wedges. J. Struc. Geol 25, 1691–1711 (2003).

Panien, M., Buiter, S. J. H., Schreurs, G. & Pfiffner, O. A. Inversion of a symmetric basin: insights from a comparison between analogue and numerical experiments. Geol. Soc., London, Spec. Pub 253, 253–270 (2006).

Panien, M., Schreurs, G. & Pfiffner, A. Mechanical behaviour of granular materials used in analogue modelling: insights from grain characterisation, ring-shear tests and analogue experiments. J. Struc. Geol. 28, 1710–1724 (2006).

Ritter, M. C., Leever, K., Rosenau, M. & Oncken, O. Scaling the sandbox—mechanical (dis) similarities of granular materials and brittle rock. J. Geophys. Res. 121, 6863–6879 (2016).

Santimano, T., Rosenau, M. & Oncken, O. Intrinsic versus extrinsic variability of analogue sand-box experiments—insights from statistical analysis of repeated accretionary sand wedge experiments. J. Struc. Geol. 75, 80–100 (2015).

Schreurs, G. et al. Analogue benchmarks of shortening and extension experiments. Geol. Soc., London, Spec. Pub. 253, 1–27 (2006).

Adam, J. et al. Shear localisation and strain distribution during tectonic faulting—new insights from granular-flow experiments and high-resolution optical image correlation techniques. J. Struc. Geol. 27, 283–301 (2005).

Global Volcanism Program. Volcanoes of the World, v. 4.8.7. Venzke, E (ed.). Smithsonian Institution. Downloaded 11 Nov 2019 https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.VOTW4-2013 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the German Science Foundation (grant Ri-916/17-1). O. Galland advised us in the scaling. M. Rosenau and F. Zwaan provided information on the quartz sand and PDMS-corundum sand mixture. Reviews by M. Cooke, G. De Pascale, and two anonymous persons contributed substantially to clarifying the content of this contribution. Finally, we thank Associate Editor J. Aslin for handling the paper and his patience in this regard.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.O.E. conceived the study, processed the data, and provided the first draft of the paper. J.O.E., P.L.G., and U.R. participated in the interpretation of the data as well as writing and editing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Communications Earth & Environment thanks Michele Cooke and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Joe Aslin, Heike Langenberg.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eisermann, J.O., Göllner, P.L. & Riller, U. Orogen-scale transpression accounts for GPS velocities and kinematic partitioning in the Southern Andes. Commun Earth Environ 2, 167 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00241-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00241-4

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.