Abstract

Topological surface states of three-dimensional topological insulator nanoribbons and their distinct magnetoconductance properties are promising for topoelectronic applications and topological quantum computation. A crucial building block for nanoribbon-based circuits are three-terminal junctions. While the transport of topological surface states on a planar boundary is not directly affected by an in-plane magnetic field, the orbital effect cannot be neglected when the surface states are confined to the boundary of a nanoribbon geometry. Here, we report on the magnetotransport properties of such three-terminal junctions. We observe a dependence of the current on the in-plane magnetic field, with a distinct steering pattern of the surface state current towards a preferred output terminal for different magnetic field orientations. We demonstrate that this steering effect originates from the orbital effect, trapping the phase-coherent surface states in the different legs of the junction on opposite sides of the nanoribbon and breaking the left-right symmetry of the transmission across the junction. The reported magnetotransport properties demonstrate that an in-plane magnetic field is not only relevant but also very useful for the characterization and manipulation of transport in three-dimensional topological insulator nanoribbon-based junctions and circuits, acting as a topoelectric current switch.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The behavior of spin-momentum-locked surface states in 3D TI-based multiterminal junctions is crucial for their use in topoelectronic and spintronic circuit applications, and Majorana-based topological quantum computation architectures1,2,3,4,5,6,7. In past studies, various transport properties of straight 3D TI-based nanowires and ribbons have been investigated theoretically and observed experimentally in micrometer- and nanometer-sized systems, e.g., weak antilocalization and quasiballistic transport with Aharonov–Bohm oscillations8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18.

In addition to magnetotransport studies, first steps have been made to use this platform for hosting exotic quasiparticle states known as Majorana bound states (MBSs), by aligning a 3D TI nanowire with an external magnetic field and combining it with an s-wave superconductor for realizing topological superconductivity via the proximity effect19,20,21,22,23. These states are of particular interest since they are promising candidates for the realization of fault-tolerant quantum computation4,6,24,25,26,27. By exploiting their nonlocal nature and nonabelian exchange statistics, it has been proposed that qubits and quantum operations can be implemented with MBSs in a very robust manner. A key operation for this approach is the braiding of different pairs of MBSs. In order to perform braiding, however, straight nanowire structures are not sufficient. More complex structures such as three-terminal junctions (referred to as tri-junctions below) and eventually networks of 3D TI nanowires are required, and the magnetic field has to be aligned appropriately. In this regard, a proper understanding of the impact of an in-plane magnetic field on the electron transport of coherent topological surface states across such junctions is essential while, unlike on straight nanowires, experimental transport studies are still lacking.

It has already been predicted theoretically that the conductance in 3D TI nanowire-based structures, such as kinks and Y-junctions, can be controlled by applying an in-plane magnetic field28. The underlying reason for these conductance properties is that the relative orientation of the magnetic field and the junction affects the transmission to the different arms through the orbital effect. In the single-channel limit, quantum transport simulations indicate that a complete pinch-off or near-perfect transparency of the topological surface state-based carrier transport can be realized to particular output legs for certain magnetic field orientations and strengths.

In this context, we have studied the low-temperature magnetotransport properties of Bi2Te3-based tri-junctions with three nanoribbon legs. In these junctions, the current is injected in a single input leg and splits into the two remaining output legs. The structures were prepared by employing selective-area molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) and the conductance was measured as a function of the angle between the magnetic field and the input lead. We have found characteristic transmission patterns with alternating optimal transmission into one of the two output legs depending on the orientation of a magnetic field aligned parallel to the plane of the junction. To explain the observed features, we developed a qualitative tri-junction transmission model, based on our findings from semiclassical considerations and quantum transport simulations (with Kwant29) of topological surface states in 3D TI-based multiterminal junctions in the presence of an external magnetic field.

Results

Magnetoconductance properties

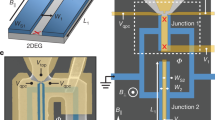

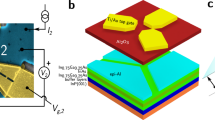

Low temperature magnetotransport measurements were performed on a T-shaped tri-junction. The sample is composed of a Bi2Te3 film at an average thickness of 14 nm that is grown selectively and capped with AlOx (see Fig. 1a for layout and “Methods” section for details on growth and fabrication). The electron phase-coherence length below T = 1 K was determined to be lϕ ≈ 240 nm (see “Methods” section). Figure 1b, c show a scanning electron micrograph of the device and a scanning transmission electron micrograph of the cross section of one of the legs, respectively. The device is contacted by Ti/Au after selectively removing the capping and it is protected by an additional layer of HfO2 grown by means of atomic layer deposition. In our setup, we apply a voltage V to the bottom terminal and ground the other two terminals while measuring the current flowing through each of the terminals as a function of the magnetic field applied in-plane. Sweeping the in-plane field strength up to 0.5 T we observe a uniform decrease in the total current Itot, which we attribute to the weak antilocalization (WAL) effect present in the individual legs of the T-junction (see Fig. 2a). The total current is calculated as the sum of the currents going into the left and right leg of the T-junction. No pronounced orientation in the WAL pattern is observed. This result is in agreement with what has been measured on similar samples of straight nanoribbons in prior experiments18,30,31.

a Schematic illustration of the layout of a T-shaped selectively-grown 3D TI nanostructure with in-plane magnetic field-driven steering effect indicated. b Scanning electron microscopy image of a T-junction device. The contacts near (far from) the T are referred to as the inner (outer) contacts. The magnetic field B is applied in-plane. The input current Itot, which is injected from the outer contact on the bottom leg, splits off into currents IR and IL, which are measured at the outer contacts on the right and left leg of the T, respectively. c Transmission electron micrograph of the cross section of an AlOx-capped Bi2Te3 nanoribbon. The scale bar indicates 50 nm. The thickness of the ribbon is determined to be 14 nm and the average width is about 135 nm. The stripes in the 3D TI layer (see inset) correspond to quintuple layers of the material.

a–c The current is measured from the bottom leg to both output legs (shown in a), and individually to the left leg (shown in b) and right leg (shown in c). The sketches on top of the plots indicate the current paths. The measurements were carried out at a temperature of 25 mK for the T-shaped tri-junction presented in Fig. 1b. The reference frame is also shown in that figure.

Steering ratio

The individual currents are measured as a function of the in-plane magnetic field components and shown in Fig. 2b–c. Unlike for the total current, a pronounced correlation along the diagonal (Bx = By) and antidiagonal (Bx = −By) of the (Bx, By)-plane can be identified for the current towards the right and the left, respectively. A robust steering pattern emerges over a large range of magnetic field strengths, with the current favoring one of the two output legs depending on the in-plane magnetic field orientation. The steering pattern is more clearly seen when plotting the steering ratio \({{{{{{{\mathcal{S}}}}}}}}{{{{{{{\mathcal{R}}}}}}}}\), defined as

as a function of the magnetic field orientation angle and strength (see Fig. 3a, details on the transformation of the experimental data set can be found in the “Methods” section). The pattern becomes more pronounced at higher field strengths and a π-periodicity as a function of the magnetic field orientation angle θ, \({{{{{{{\mathcal{S}}}}}}}}{{{{{{{\mathcal{R}}}}}}}}\propto \sin (2\theta )\), can easily be identified when taking a line cut for a fixed magnetic field strength (see Fig. 3c).

a, b The steering ratio \({{{{{{{\mathcal{S}}}}}}}}{{{{{{{\mathcal{R}}}}}}}}\) of the T-shaped tri-junction presented in Fig. 1b as a function of the in-plane magnetic field orientation θ (with the direction relative to the T-junction indicated by the red arrows at the top) and the field strength ∣B∣, as obtained from the transport measurements (see Fig. 2) in (a), and from the qualitative transmission model, as discussed in the Main Text and derived in Supplementary Note 2, in (b). c Line cuts of the steering ratio for increasing magnetic field strengths, obtained from the experimental data (dashed lines) and model results (solid lines) presented in (a) and (b), respectively. The scale indicated on the right (left) is for the experimental (model) values and the curves are shifted up by multiples of 0.5 × 10−2 (0.2).

Note that the intrinsic, magnetic field-independent asymmetry of the junction is subtracted from the steering ratio in Equation (1). It is clear from the range of the individual currents in Fig. 2 that the measured currents already have some asymmetry in the absence of an external magnetic field. This asymmetry can be attributed to small structural differences in the wire legs and different contact resistances, for example, that are not directly related to the transmission of 3D TI surface states across the tri-junction. Further note that the angle dependence of the steering ratio immediately rules out an explanation based on the Hall effect due to a possible misalignment of the external magnetic field and sample planes, as it would give rise to a 2π-periodic pattern. Other possible symmetry-breaking mechanisms that are unrelated to the tri-junction itself are considered in the Discussion section below and more details on them are provided in Supplementary Note 2.

Temperature dependence

Magnetotransport measurements have been conducted for a Y-shaped tri-junction at different temperatures to resolve the temperature dependence of the observed steering pattern (see Supplementary Note 1 for the current measurement results). In general, we find that the dependence of the current on the magnetic field strength and orientation decreases for increasing temperature. This can be quantified with the standard deviation of the current data over all the measured magnetic fields, i.e., −0.7 T ≤ Bx,y ≤ 0.7 T, and comparing this quantity at different temperatures. The results obtained from the Y-junction magnetotransport data are shown in Fig. 4. The standard deviation of the total current displays a slow but steady decrease for increasing temperatures, which can be attributed to the change in the field strength dependence due to the effect of WAL near ∣B∣ = 0. The standard deviation of the individual currents shows a very different temperature dependence. The standard deviation has a much steeper decrease above T = 200 mK and appears to saturate below this temperature. This crossover in the profile coincides with the appearance of the steering pattern below T ≈ 200 mK.

The data is extracted from current data sets over different in-plane magnetic field strengths and orientations (see Supplementary Note 1 for current data), evaluated at different temperatures.

Origin of steering effect

The left-right symmetry breaking of the tri-junction and the steering effect of the current can be explained by considering the impact of the orbital effect on 3D TI nanowire surface states that form the input and output states of the tri-junction. The spectrum of these surface states in the presence of an aligned external magnetic field is well described by19,32

with vD the Dirac velocity of the surface state cone, k the wave vector along the direction of the wire, and 2πj/P the generalized transverse wave vector that contains contributions of the transverse orbital motion, the nontrivial Berry phase (i.e., equal to π), and the flux enclosed by the perimeter P of the nanowire cross section.

The crucial aspect for the steering effect is the orbital effect due to the nonaligned magnetic field component. It gives rise to a Lorentz force on the side facets of the nanoribbon that traps certain surface-state transport modes on the top or the bottom surface of the legs of the tri-junction, depending on the relative orientation of the in-plane magnetic field with respect to that leg. This type of trapping can be understood by considering the semiclassical trajectory of a surface-state charge carrier (see Fig. 5a). On the top and bottom surfaces of the nanowire, the trajectory is not affected, but a circular motion is induced on the side facets when the magnetic field is not perfectly aligned with the leg. The gyroradius Rg of that circular motion is given by

with EF the Fermi level energy (with respect to the Dirac point energy of the surface state cone), e the elementary charge, \({B}_{\perp }=| {{{{{{{\bf{B}}}}}}}}| \cos (\theta -{\gamma }_{{{{{{{{\rm{leg}}}}}}}}})\) the component of the magnetic field perpendicular to the direction of the ribbon (with θ and γleg the orientation angles of the in-plane magnetic field and the ribbon, respectively). Based on this gyroradius, the height of the ribbon (~14 nm), and the velocity vector of a specific 3D TI surface state on the side facet, we can estimate whether the surface state is able to traverse the side facet against the direction of the trapping (Lorentz) force. If this is not the case, the charge carrier is effectively trapped on the top or bottom surface of the nanoribbon while it moves towards (or away from) the junction, as the direction of the trapping force is the same on the two side facets of the ribbon. This direction is given by the sign of \(\sin (\theta -{\gamma }_{{{{{{{{\rm{leg}}}}}}}}}){v}_{\parallel }\), with v∥ the velocity component of the surface state along the direction of the ribbon. The force points towards the top (bottom) surface when this sign is negative (positive).

a The semiclassical trajectory of a 3D TI nanoribbon surface state in the presence of a magnetic field that is not aligned with the ribbon. The maximal transverse distance Δz that the surface state can travel on the side surface is indicated. In this case, the charge carrier cannot reach the top surface and is effectively trapped on the bottom surface. b The inverse transverse distance that the surface states of the different subbands [see Eq. (2)] are able to travel against the Lorentz force of a nonaligned in-plane magnetic field on the side surface of a nanoribbon is shown as a function of the angle θ − γleg between the magnetic field and the ribbon orientation. Depending on this angle (and considering v∥ > 0), the direction of the force points towards the top (solid lines) or bottom (dashed lines) surface. The subband states that cannot traverse the side surfaces against the Lorentz force are indicated in color and the transverse-mode index l is specified. A 150 nm-wide and 14 nm-high nanoribbon (based on the sample dimensions) with EF = 86 meV and vF = 5.5 × 105 m/s (reasonable assumptions, corresponding to a 2D charge density of approximately 5 × 1011 cm−2), and a magnetic field strength of 0.5 T have been considered. The inverse wire thickness is indicated by the red dotted line.

The trapping effect can effectively block the transmission across a tri-junction to one of the output legs when the input channel and corresponding output channel on one of the output legs are trapped on opposite surfaces. Based on this trapping effect, we can construct a qualitative transmission model by assuming that the transmission across the tri-junction, which is otherwise expected to be left-right symmetric from general symmetry considerations, is suppressed when the incoming surface state and the corresponding output state are trapped on opposite surfaces (see Supplementary Note 2 for a derivation of the model). The overall transmission is then obtained by summing over all the incoming surface-state channels of the input leg of the tri-junction, considering the geometry of the leg, the Fermi level energy for the 3D TI surface states, and the external magnetic field. The steering ratio obtained from the qualitative transmission model is compared to the experimentally obtained steering ratio profile in Fig. 3 and they are in good qualitative agreement, both regarding the angular dependence as well as the field strength dependence, with the steering ratio profile becoming more pronounced as the magnetic field strength and corresponding trapping force increase.

Discussion

The steering effect across a tri-junction due to trapped surface states on the top or bottom surface of a 3D TI nanoribbon in the presence of an external in-plane magnetic field has been explained by considering semiclassical trajectories for the charge carriers. However, the phenomenology can also be confirmed with quantum transport simulations, considering a tight-binding model for 3D TIs and making use of the software package Kwant29. This analysis is presented in Supplementary Note 3. Further note that, as the topological surface states are spin-momentum-locked, the steering effect would naturally induce a steering of spin current as well, which could be considered for spin filter applications33.

The in-plane magnetic field is not the only possible source of left-right symmetry breaking for the current in our experimental setup. An overview of the alternative symmetry breaking mechanisms is presented in Supplementary Note 4, and it is discussed in detail what is their expected steering ratio profile and why they cannot be responsible for the observed π-periodic steering ratio profile.

While the steering ratio profiles obtained experimentally and from the transmission model are in good qualitative agreement, their amplitudes differ by a factor of around 25. This discrepancy can be attributed to the contribution of bulk states to the total current in the experiment, something that is not taken into account in the transmission model. The bulk state properties are only weakly affected by the orbital effect of the magnetic field and are not subject to the trapping effect that affects the topological surface states. Hence, the scaling factor of 25 is expected to reflect the ratio of bulk versus surface state current in the current measurements. While we cannot disentangle the bulk and surface state contributions in our experimental setup, a current contribution from the bulk that is up to one or even two orders of magnitude larger than the surface state contribution is expected, from the high charge carrier contribution that is obtained from the Hall bar characterization (see Methods section). Furthermore, considering that we have obtained the steering ratio profile from the transmission model assuming a surface state charge density of ~1.5 × 1012 cm−2, this would imply a total charge density that is 25 times larger.

An important observation in support of our transmission model is the temperature dependence of the steering pattern. This crossover temperature, above which the steering pattern disappears, is in reasonable agreement with the temperature at which the phase-coherence length becomes comparable to the perimeter around the cross section of the legs of the tri-junction (see “Methods” section). Hence, the temperature dependence of the individual currents signifies the importance of 3D TI surface states retaining their phase coherence along the complete perimeter of the ribbon, similar to the magnetotransport pattern of flux quantum-periodic magnetoconductance oscillations appearing in straight 3D TI nanoribbons at low temperatures14,16,18. In that case, the oscillations originate from the Aharonov–Bohm effect acting on the surface state subband spectrum, which requires phase coherence along the perimeter of the ribbon for the surface states to properly enclose the magnetic flux. In this case, however, it is the trapping effect that relies on the coherent propagation of the surface state quasiparticles along the perimeter of the ribbon such that the surface state solutions can become depleted on either the top or the bottom of the wire by the Lorentz force acting on the side facets.

As the trapping effect is a direct consequence of the orbital effect on the surface-state charge carrier, we cannot immediately rule out the possibility that the steering effect is rooted in trivial surface states rather than topological surface states. For example, there could be surface states that originate from trivial bulk states due to bulk bending34, which then get trapped by the external magnetic field. However, this scenario is less probable because of the following two reasons. First, phase-coherence around the perimeter of the cross section, which is an important requirement for the trapping effect and is supported by the temperature dependence, as discussed in the previous paragraph, is much more difficult to realize with nontopological surface states, e.g., a conventional 2D electron gas, that are more sensitive to disorder and related localization effects. Second, the trapping effect is expected to be more robust and pronounced for topological surface states as compared to trivial surface states because of spin-momentum locking. The trapping force flips sign when the velocity along the direction of the nanoribbon is reversed. For trivial surface states, such a change of the velocity can easily arise due to elastic scattering processes in the presence of disorder. For topological surface states, however, spin-momentum locking forbids direct backscattering and generally suppresses scattering events that flip the sign of the velocity. For a more quantitative comparison, we performed quantum transport simulations of a T-junction in the single-channel regime with a topological surface state, a trivial surface state, and a bulk metallic state (see Supplementary Note 3). The resulting steering pattern agrees well with the trapping-based transmission model as well as the experimental data, and is robust against disorder, but only for the topological surface state.

In summary, we have observed an in-plane magnetic field-driven steering effect that breaks the left-right symmetry of the transmission of 3D TI nanoribbon surface states across three-terminal junctions. The effect can be attributed to the interplay of the phase-coherent topological surface states and the orbital effect on the side facets that causes these states to be trapped on the top or bottom surface of a nanoribbon, depending on the relative orientation of the ribbon and the magnetic field. This trapping effect can suppress the transmission to one of the two output legs of a 3D TI nanoribbon-based tri-junction, which gives rise to a steering effect that can be understood from semiclassical considerations and quantum transport simulations. The steering effect is well described by a qualitative transmission model that provides good agreement with the theoretical findings and the experimentally obtained steering ratio profile of the electrical current. The physical origin of the steering effect is corroborated by the temperature dependence of the steering ratio profile, which indicates the importance of the phase coherence of topological surface states around the full perimeter of the ribbon legs. Our experimental and theoretical results reveal interesting magnetotransport properties of 3D TI-based tri-junctions in the presence of an in-plane magnetic field that are relevant for their application in topological material-based quantum technologies.

Methods

Growth and fabrication

In Fig. 1a a schematic of the T-shaped sample layout is shown. For substrate preparation, first, a silicon (111) wafer was covered with a 6-nm-thick thermally-grown SiO2 layer. Subsequently, a 25-nm-thick amorphous SiNx layer was deposited using plasma-enhanced chemical vapour deposition. The pattern for the subsequent selective-area growth was defined by electron beam lithography followed by reactive ion etching (CHF3/O2) and wet chemical etching using hydrofluoric acid. The 14-nm-thick topological insulator Bi2Te3 film was grown selectively by means of MBE on the Si(111) surface18,30,31,35. The epitaxial layer was capped in-situ by a ~3-nm-thick AlOx layer36. A scanning transmission electron micrograph of the cross section lamella of a 135-nm-wide nanoribbon as used in the T- and Y-junction prepared by focused ion beam milling is shown in Fig. 1c. The epitaxial layers are crystallographically aligned with the substrate. The Ohmic contacts composed of a 5-nm-thick Ti layer and a 100-nm-thick Au layer were prepared by electron beam evaporation after development and removing the AlOx capping in the developed areas by argon sputtering. Finally, the device is capped with a HfO2 layer by atomic layer deposition. In Fig. 1b a scanning electron micrograph of an exemplary contacted T-junction is shown.

Material characterization

Using a standard four-probe lock-in Hall setup in a variable temperature insert, Hall measurements were performed on devices of different sizes grown by means of MBE during the same run and published by Rosenbach et al.18. The authors find a total charge carrier concentration of n2D = (6.8–9.5) × 1013 cm−2 and a mobility of μ = (307–374) cm−2/Vs from analyzing the Hall data. Additionally, Shubnikov-de Haas oscillations are observed in a 500 nm-wide Hall device. Based on these oscillations, the 2D sheet carrier concentration is found to be nSDH = 5.3 × 1011 cm−2, at a mobility of μ = 1997 cm−2/Vs. The latter values can be attributed to the topological surface states, which leads to an estimated Fermi level of EF = 86 meV with respect to the Dirac point. Furthermore, a phase-coherence length of about lϕ(T < 1 K) ≈ 240 nm is estimated from the magnetoresistance data in a nanoribbon. This value for lϕ is of the same order of magnitude as the perimeter of the cross section of the tri-junction legs for the device presented in this work.

Magnetotransport measurements

The magnetotransport measurements were carried out in a dilution refrigerator at a base temperature of T = 25 mK. The system is equipped with a 1-1-6 T vector magnet. For the electrical setup we refer to Fig. 1b. In addition, every line is equipped with a set of filters adding a resistance of about 3.6 kΩ each. In the experiment we use lock-in amplifiers at fLI = 28.3 Hz and an operational amplifier-based voltage source to apply a bias voltage of 100 μV to the bottom terminal. The lock-in amplifiers are equipped with a current-to-voltage converter providing a virtual ground to the other two terminals. The voltage bias leads to a current Itot through the device input. The current then splits off into IR and IL, depending on the resistances of the two individual paths. Scanning the magnetic field along the different in-plane directions then yields the 2D current maps, as shown in Fig. 2 and in Supplementary Note 1.

Data analysis

In order to compare the experimental data with the theoretical model the magnetic field components of the steering ratio were transformed from Cartesian coordinates with point distances \({\delta }_{{B}_{x}}={\delta }_{{B}_{y}}=10\ \,{{\mbox{mT}}}\,\) into polar coordinates and projected onto a rectangular grid with point distances δB = 6 mT and δϕ = 0.06 rad using linear interpolation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are made available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. The experimental data, the simulation source code, and the simulated data that supports the findings of this study are available as source data files from the Jülich DATA repository (https://doi.org/10.26165/JUELICH-DATA/CX10EO).

References

Moore, J. E. The birth of topological insulators. Nature 464, 194–198 (2010).

Alicea, J., Oreg, Y., Refael, G., von Oppen, F. & Fisher, M. P. A. Non-Abelian statistics and topological quantum information processing in 1D wire networks. Nat. Phys. 7, 412–417 (2011).

Van Heck, B., Akhmerov, A. R., Hassler, F., Burrello, M. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Coulomb-assisted braiding of Majorana fermions in a Josephson junction array. New J. Phys. 14, 035019 (2012).

Hyart, T. et al. Flux-controlled quantum computation with Majorana fermions. Phys. Rev. B 88, 035121 (2013).

Aasen, D. et al. Milestones toward Majorana-based quantum computing. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031016 (2016).

Litinski, D., Kesselring, M. S., Eisert, J. & von Oppen, F. Combining topological hardware and topological software: color-code quantum computing with topological superconductor networks. Phys. Rev. X 7, 031048 (2017).

Schüffelgen, P. et al. Exploiting topological matter for Majorana physics and devices. Solid-State Electronics 155, 99–104 (2019).

Peng, H. et al. Aharonov-Bohm interference in topological insulator nanoribbons. Nat. Mater. 9, 225–229 (2010).

Bardarson, J. H., Brouwer, P. W. & Moore, J. E. Aharonov-Bohm oscillations in disordered topological insulator nanowires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 156803 (2010).

Xiu, F. et al. Manipulating surface states in topological insulator nanoribbons. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 216–221 (2011).

Bardarson, J. H. & Moore, J. E. Quantum interference and Aharonov-Bohm oscillations in topological insulators. Rep. Prog. Phys. 76, 056501 (2013).

Dufouleur, J. et al. Quasiballistic Transport of Dirac Fermions in a Bi2Se3 Nanowire. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 186806 (2013).

Jauregui, L. A., Pettes, M. T., Rokhinson, L. P., Shi, L. & Chen, Y. P. Magnetic field-induced helical mode and topological transitions in a topological insulator nanoribbon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 345 (2016).

Arango, Y. C. et al. Quantum transport and nano angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy on the topological surface states of single Sb2Te3 nanowires. Sci. Rep. 6, 29493 (2016).

Dufouleur, J. et al. Weakly-coupled quasi-1D helical modes in disordered 3D topological insulator quantum wires. Sci. Rep. 7, 45276 (2017).

Ziegler, J. et al. Probing spin helical surface states in topological HgTe nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 97, 035157 (2018).

Xypakis, E., Rhim, J.-W., Bardarson, J. H. & Ilan, R. Perfect transmission and Aharanov-Bohm oscillations in topological insulator nanowires with nonuniform cross section. Phys. Rev. B 101, 045401 (2020).

Rosenbach, D. et al. Quantum transport in topological surface states of selectively grown Bi2Te3 nanoribbons. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 2000205 (2020).

Cook, A. & Franz, M. Majorana fermions in a topological-insulator nanowire proximity-coupled to an s-wave superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 84, 201105 (2011).

Cook, A. M., Vazifeh, M. M. & Franz, M. Stability of Majorana fermions in proximity-coupled topological insulator nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 86, 155431 (2012).

Schüffelgen, P. et al. Selective area growth and stencil lithography for in situ fabricated quantum devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 825–831 (2019).

Liu, P., Williams, J. R. & Cha, J. J. Topological nanomaterials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 479–496 (2019).

Bai, M. et al. Novel self-epitaxy for inducing superconductivity in the topological insulator (Bi1−xSbx)2Te3. Phys. Rev. Materials 4, 094801 (2020).

Ivanov, D. A. Non-abelian statistics of half-quantum vortices in p-wave superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 268–271 (2001).

Kitaev, A. Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 303, 2–30 (2003).

Freedman, M., Kitaev, A., Larsen, M. & Wang, Z. Topological quantum computation. Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 40, 31–38 (2003).

Hassler, F., Akhmerov, A. R. & Beenakker, C. W. J. The top-transmon: a hybrid superconducting qubit for parity-protected quantum computation. New J. Phys. 13, 095004 (2011).

Moors, K. et al. Magnetotransport signatures of three-dimensional topological insulator nanostructures. Phys. Rev. B 97, 245429 (2018).

Groth, C. W., Wimmer, M., Akhmerov, A. R. & Waintal, X. Kwant: a software package for quantum transport. New J. Phys. 16, 063065 (2014).

Weyrich, C. et al. Phase-coherent transport in selectively grown topological insulator nanodots. Nanotechnology 30, 055201 (2019).

Kölzer, J. et al. Phase-coherent loops in selectively-grown topological insulator nanoribbons. Nanotechnology 31, 325001 (2020).

Rosenberg, G., Guo, H.-M. & Franz, M. Wormhole effect in a strong topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B 82, 041104 (2010).

Bellucci, S. & Onorato, P. Spin filtering and spin Hall accumulation in an interferometric ballistic nanojunction with Rashba spin-orbit interaction. Phys. Rev. B 77, 075303 (2008).

Bianchi, M. et al. Coexistence of the topological state and a two-dimensional electron gas on the surface of Bi2Se3. Nat. Commun. 1, 128 (2010).

Kampmeier, J. et al. Selective area growth of Bi2Te3 and Sb2Te3 topological insulator thin films. J. Cryst. Growth 443, 38–42 (2016).

Lang, M. et al. Revelation of topological surface states in Bi2Se3 thin films by in situ Al passivation. ACS Nano 6, 295 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy—Cluster of Excellence Matter and Light for Quantum Computing (ML4Q) EXC 2004/1—390534769, by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) via the Quantum Futur project “MajoranaChips” (Grant No. 13N15264) within the funding program Photonic Research Germany, and by the Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Regional Development and Energy within Bavaria’s High-Tech Agenda Project “Bausteine für das Quantencomputing auf Basis topologischer Materialien mit experimentellen und theoretischen Ansätzen” (grant allocation no. 07 02/686 58/1/21 1/22 2/23).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K., A.R.J., E.Z., and D.R. were involved in the sample fabrication, A.R.J., P.S. and G.M. grew the thin film using MBE, J.K., E.Z., and D.R. performed the low temperature transport measurements, L.K. prepared the lamella and did the high-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy analysis, K.M. performed the simulations and J.K. and K.M. analyzed the data. K.M., J.K., T.S., T.L.S., and H.L. wrote the paper with contributions from all co-authors, the project was supervised by D.G., T.L.S., H.L., and T.S. and all authors contributed to the discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Communications Materials thanks Joseph Dufouleur and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Aldo Isidori.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kölzer, J., Moors, K., Jalil, A.R. et al. In-plane magnetic field-driven symmetry breaking in topological insulator-based three-terminal junctions. Commun Mater 2, 116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-021-00213-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-021-00213-3