Abstract

Boron-based two-dimensional materials are of interest for use in electronic devices and catalytic applications, for which it is important that they are chemically stable. Here, we explore the chemical stability of hydrogen boride nanosheets in water. Experiments reveal that mixing hydrogen boride and water produces negligible amounts of hydrogen, suggesting that hydrolysis does not occur and that hydrogen boride is stable in water, which is in contrast to most boron hydride materials. First-principles calculations reveal that the sheets interact weakly with water even in the presence of defects and that negatively charged boron prevents the onset of hydrolysis. We conclude that the charge state of boron and the covalent boron-boron bond network are responsible for the chemical and structural stability. On the other hand, we found that proton exchange with hydrogen boride nanosheets does occur in water, indicating that they become acidic in the presence of water.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The stability of materials, in general, is a crucial property in the development and deployment of devices; they must withstand the thermal, mechanical, and chemical influences of the operating environment. In the past few decades, theoretical studies have explored two-dimensional boron nanomaterials and predicted that different structures exist1,2,3,4. However, the difficulty of syntheses arises from the electron-deficient nature of a boron atom where three valence electrons cannot fill the valence shell through bonding. Despite this challenge, quasiplanar boron clusters have been synthesized5,6, and a few predicted structures, such as β12, δ3, and χ3, have been successfully synthesized on metal surfaces by using a molecular beam epitaxy in ultrahigh vacuum7,8,9,10. The resulting two-dimensional boron nanosheets are inevitably confined on the metal surface, and their removal may lead to an unstable free-standing form. As an alternative, hydrogenation can be used as an electron-donor, in exchange for the metallic surface, to form a pseudo-free-standing product11,12. In a recent study, hydrogenation of a boron sheet on a silver surface has shown remarkable improvements on its chemical stability upon exposure to ambient condition13. Another advantage of this method is that the hydrogenation is a reversible process via annealing at low temperatures.

Recently, two-dimensional hydrogen boride nanosheets (HB sheets) were synthesized14, which were derived from magnesium diboride (MgB2) via cation exchange and liquid exfoliation at room temperature (~298 K) and in N2 environment. Unlike the synthesis on metal surfaces, the fabrication method shows that a low-temperature preparation of two-dimensional boron nanosheets is possible. The atomic structure cannot be directly observed with morphological characterization via microscopy techniques; the structure can only be inferred from indirect observation techniques such as the X-ray pair distribution function (XPDF). Accordingly, a model was developed to best fit the experimental XPDF data. The model consists of a slightly distorted honeycomb boron sheet and passivating hydrogen atoms, which was found to have semi-metallic electronic properties15,16. In addition, studies have reported that HB sheets show promising performance in Li/Na ion and H2 storage17,18. Despite the interest in HB sheets, the studies conducted are still limited mainly due to their infancy.

For the development of HB sheet-based devices, the HB sheets should be stable and not easily degraded in operating environments, specifically in water, which is present in common operating environments19. To probe the stability property, we tried exposing the HB sheets in air and found by visual inspection that moisture was absorbed. This phenomenon poses the question of whether HB sheets are reactive to water or hygroscopic. This is especially concerning because some boron hydride materials are reactive to water. For example, boranes react with water to form hydrogen and boric acid (B(OH)3) as a result of a sequential hydrolysis reaction. Specifically, in the case of diborane (B2H6), the reaction is known to proceed as follows20:

The hydrolysis reaction was also reported to occur in the degradation process of MgB221, which is the starting material for the production of HB sheets. In addition, the hydrolysis reaction forms B(OH)3 during the synthesis of HB sheets, and thus HB sheets were prepared under nitrogen atmosphere14. If the HB sheets have a similar chemical reactivity, then the following hydrolysis reaction can be expected:

Alternatively, if the hydrolysis reaction does not occur by pouring water and if the HB sheets can be obtained again after drying the sample, then they can be regarded to have chemical stability against water.

In this study, we focused on determining the chemical stability of HB sheets with water. We conducted experiments and determined that a hydrolysis reaction does not largely occur, when the HB sheets are exposed to water. Furthermore, we investigated the reaction of water at the atomic scale by characterizing the HB sheets–water interaction from the perspective of structure, energy, and bonding by means of density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The results show that water reacts weakly with the HB sheet and that boron in the HB sheet is negatively charged, which prevents the onset of hydrolysis.

Results and Discussion

Reaction with water

To clarify the chemical stability issue, we examined the reaction of HB sheets with water at room temperature (~298 K). We placed HB sheets into distilled water, and the volume of gas generated was measured by collecting it over water. The collected gas was also frequently sampled and analyzed using a gas chromatograph. We found that only H2 gas was produced by mixing the HB sheets and water with an amount corresponding to a small percentage of the expected H2 yield from Eq. (5). Figure 1a shows an example of H2 production as a function of time after mixing the HB sheets and water. In this case, HB sheets (58.04 mg) and distilled water (20 mL) were mixed at 400 rpm using a magnetic stirrer at room temperature (~298 K). H2 was then obtained with 2.8 mL as a saturated amount, which corresponds to 1.3% of the expected H2 amount by the hydrolysis reaction. At 400 min, we added 50 mL of water, which did not cause any additional gas production, implying that the saturation of H2 was not due to the specific equilibrium condition.

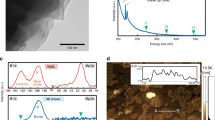

a H2 amount as a function of time from the mixture of HB (58.04 mg) and distilled water (20 mL), where water (50 mL) was added at 400 min. b XPS B1s spectra after drying the mixture of water (10 mL) with HB (1.2–21.9 mg). c B1s (193 eV) peak component as a function of the HB amount in the B1s spectra shown in (b), inset shows the photograph of the sample after drying the mixture of HB and water at 393 K.

Analysis of reaction products

To examine the states of the HB sheets after the interaction with water, we conducted X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements on HB sheets after drying the HB sheets–water mixture at 393 K, as shown in Fig. 1b. Here, we first mixed distilled water (10 mL) and the HB sheets in varying amounts (1.2–21.9 mg) and then dried the mixture by heating at 393 K on a hot-plate in air. In all cases, a light-yellow powder was obtained, as shown in the inset in Fig. 1c, and the XPS B1s shows the dominant peak at ~188 eV. The peak corresponds to the negatively charged B and is consistent with the peak obtained from the as-prepared HB sheets14. In some cases, an additional peak appeared at ~193 eV, which can be assigned as an oxidized B peak14. The percentage of the oxidized B peak is plotted as a function of the HB amount in Fig. 1c. We found no clear correlation between the amount of HB and the percentage of the oxidized B peak. Moreover, the oxidized B peak is not as significant as the peak at ~188 eV. The results indicate that the charge state of B was maintained, and that the hydrolysis reaction of HB did not occur even at 393 K in water. The small amount of H2 produced (Fig. 1a) may be due to the limited number of reactive sites.

These experimental results indicate that the HB sheets are chemically stable toward water at room temperature (~298 K) and that only some of the specific sites, such as defects and/or edges with specific species (e.g., –OH or –O) in the HB sheet, may react with water. To gain an insight into the active site, we conducted reaction cycle experiments. Figure 2a shows the amount of H2 as a function of time for the mixture of H2O (2.0 mL) and fresh HB sheets (100 mg) and for the mixture with recycled HB sheets which were obtained by drying the mixture with H2O at 353 K after 1440 min (second cycle). In the first cycle, 17.0 mL of H2 was collected after 1440 min, which corresponds to 4.5% of the expected H2 amount by the hydrolysis reaction. The amount of H2 was slightly larger than the value shown in Fig. 1a (1.3 %), presumably because the sample contains more reactive sites toward hydrolysis. On the other hand, negligible amount of H2 was generated from the recycled HB, indicating that a limited number of the reactive sites for hydrolysis inherently exist in the material, and they are not newly created during the process, in which HB is mixed with water and dried at 353 K.

a H2 amount as a function of time for the mixture of H2O (2.0 mL) and HB sheets (100 mg) and that for the recycled HB (HB dried at 353 K after 1440 min from the mixture with H2O). b pH change as a function of time for the mixture of H2O (2.0 mL) and HB sheets (100 mg) and that for D2O and the recycled HB (HB dried at 353 K after 1440 min from the mixture with H2O). c pKa derived from the pH change after mixing water and HB sheets with various HB amount. d Fourier transform infrared absorption spectroscopy results for the HB sheets, the recycled HB sheets obtained by drying the mixture of HB and H2O after 1440 min after mixing (dHB), recycled HB obtained by drying HB in D2O after 1440 min after mixing, and recycled dHB obtained by drying the mixture of dHB and D2O after 1440 min after mixing. The assignment of the absorption peaks was based on the previous report21. e Mass analysis of produced gas after the mixing H2O and HB sheets. m/z denotes the mass-to-charge ratio. f Mass analysis of produced gas after the mixture of D2O and HB sheets. The horizontal axis in (e) and (f) indicates time after injection of produced gas in the apparatus.

Proton exchange in water

We measured the pH for the mixture of HB sheets and water, and that for the mixture of recycled HB sheets and heavy water (D2O) as a function of time (Fig. 2b). We found that pH decreased immediately after mixing HB into distilled water. The pH change was much faster than the hydrolysis reaction. In sharp contrast to the hydrolysis reaction, the pH change was reproduced in the second cycle, indicating that the proton exchange with the HB sheets occurs in water. We measured pH as a function of HB amount in water before and after mixing water with HB sheets and estimated the acidity constant (pKa, Ka is acid dissociation constant) to be 3.5 ± 0.2 (Fig. 2c) based on the pH change and the following assumption: Ka = [H+][B−]/[HB], where [H+], [B−], and [HB] are molar density of H+, B−, and HB, respectively. We also conducted the Fourier transform infrared absorption spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis of fresh and recycled HB sheets (Fig. 2d). We found the B-D, B-D-B, and O-D vibrational signatures in the spectrum of the HB sheets after the second cycle with D2O, indicating that D of D2O was exchanged with hydrogen of HB sheets even after the first cycle with H2O. These results imply that proton release from the HB sheets occurs from the less-reactive site to hydrolysis reaction.

If hydrogen at the active site for the hydrolysis reaction is involved in the proton exchange reaction in D2O, the amount of D2 produced is expected to be larger than that of HD, because the proton exchange is faster than hydrolysis reaction, and because the amount of D in heavy water is larger than H in HB. To verify this hypothesis, we examined the produced gas from the mixture of HB and D2O as well as that of HB and H2O by mass spectrometer (Fig. 2e, f). In the case of HB-D2O mixture, H2, D2, and HD gases were detected with the intensity ratio of H2:D2:HD = 1:1:2. This result indicates that the active site for the hydrolysis reaction in the HB sheets is different from that for the proton-exchange, presumably because of the different natures of B atoms at and/or near these sites.

These experimental results indicate that HB sheets are stable against hydrolysis reaction, whereas proton release can easily occur via the proton exchange with HB in water.

Computational model

To further probe on the HB sheet–water interaction at the atomic scale, we employed DFT calculations on the model structure derived from the XPDF (Fig. 3a)14. The model structure considered here is the one originally proposed to represent the local structure14 and to discuss the fundamental nature of the HB sheet–water interaction, whereas the real sample structure has no long-range order and consists of a distorted hexagonal boron network structure with B–H and B–H–B bonds22. Both the calculated structural parameters (Table 1) and semi-metallic band structure (Fig. 3b) are consistent with those in similar studies14,15,16,23. Moreover, the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) and van der Waals (vdW) inclusive density functional (rev-vdW-DF2) produced similar values, suggesting that the vdW forces play a minor role in the HB sheet (see Methods for computational details).

In addition to the pristine HB sheet, we considered a few vacancy-defective HB sheets (e.g., H (\({V}_{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}\)), B (\({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}\)), HB (\({V}_{{{{{{\rm{HB}}}}}}}\)), BH2 (\({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}_{2}}\)), and H2 (\({V}_{{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}_{2}}\)) vacancies; see Supplementary Fig. 1 for the structures) to examine if the defects lead to the creation of highly reactive sites. The most likely vacancy to appear was selected by comparing their corresponding formation energies, Ef, defined as

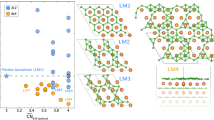

where Edef and Eperf represent the total energies of vacancy-defective and pristine systems, respectively, and \({n}_{i}\) and \({\mu }_{i}\) represent the number and chemical potential, respectively, of the removed atomic species i24,25. Herein, i is either H or B, depending on which atom was removed from the pristine system. The H and B chemical potentials are referenced to 1/2 of the total energy of H2 (\({E}_{{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}_{2}}\)) and 1/12 of the total energy of the α-rhombohedral phase boron (\({E}_{{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}_{12}}\)), and are denoted as \({\Delta \mu }_{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}\) and \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}\), respectively. All the vacancy defects considered here have the possibility to appear, as shown in the phase diagram (Fig. 4a). Figure 4b shows the formation energy as a function of \({\Delta \mu }_{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}\) at \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}=0\) and that as a function of \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}\) at \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}=0\). We can see that at \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}=0\) and \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}=0\), HB sheets with \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}\) and \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}\) (Fig. 4c) are the first and second most stable phases with the formation energies of 0.99 eV and 2.14 eV, respectively.

a Phase diagram for the stable defect in HB in the (\({\Delta \mu }_{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}\), \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}\)) space. b Formation energy as a function of \({\Delta \mu }_{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}\) at \({\Delta \mu }_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}=0\) (left) and that as a function of \({\Delta \mu }_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}\) at \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}=0\) (right). c Visual representation of the optimized structures of pristine, H vacant (\({V}_{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}\)) and B vacant (\({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}\)) HB sheets. Positions of H and B atoms removed are indicated by open squares.

Water adsorption

We studied the adsorption of a single water molecule on pristine and vacancy-defective HB sheet models. A water molecule was relaxed on top of the pristine and defective HB sheets at different adsorption sites and configurations (see Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). The most stable adsorption structures are shown in Fig. 5. We found no significant structural deformation upon adsorption, suggesting that the HB sheet is less reactive to water or that the activation energy is needed for water dissociation. We simulated the dissociation of H2O on H-vacant HB sheet and found that the dissociated state (OH-adsorbed pristine HB sheet) is thermodynamically stable, but the process requires an activation energy of 0.96 eV (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, the water molecule prefers to have a tilted configuration in which one of the H atoms of water is nearest to the B atom of HB sheet in all cases considered here. This response is consistent with the negatively charged B atom in the HB sheet reported in Ref. 14 based on the B 1 s core level position measured by XPS and evaluated by DFT. Careful charge analyses were conducted and will be discussed in more detail later.

We calculated the adsorption energy of water as

where \({E}_{{{{{{\rm{HB}}}}}}}\), \({E}_{{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}_{2}{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}}}\), and \({E}_{{{{{{\rm{HB}}}}}}-{{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}_{2}{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}}}\), are the total energies of the HB sheet with or without a defect, water molecule, and water adsorbed HB sheet, respectively. Among the three phases (pristine, H-vacant, and B-vacant), the pristine HB sheet had the weakest interaction, whereas the B-vacant HB sheet had the strongest interaction (Table 2). This trend is expected because B-vacant HB sheet presents more reactive sites for water adsorption. Despite the more reactive nature of B-vacant HB sheet, its interaction with water is still considerably weak. This trend was consistent when the adsorption energies were calculated with the rev-vdW-DF2, but the adsorption energies were significantly higher, indicating that vdW interaction plays an important role in the HB sheet–water interaction. Nevertheless, the magnitudes of the adsorption energies are still smaller than those of typical chemisorption energies, suggesting that the interaction is more of a vdW type. Note that the calculated adsorption energy serves as the upper bound for the HB sheet–water interaction because only one water molecule was introduced. If more water molecules were introduced, then competitive water hydrogen bonding would weaken the HB sheet–water interaction. We confirmed the weakening of the HB sheet–water interaction by performing calculations with an H2O dimer on H-vacant HB sheet (see Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5). To gain further insight into the HB sheet–water interaction, we also calculated the density of states (DOS) of the adsorbed systems and the molecular orbitals (MOs) of the water molecule adsorbed on the HB sheets (see Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). We found that, in all cases, the hybridization of MOs with the wavefunctions of the HB sheet is negligibly small, and the MO character of the water molecule is retained, implying that there is no significant chemical bonding between water and the HB sheet.

Charge density difference analysis of HB sheet–water

We then analyzed the interaction from the perspective of charges. We calculated the charge density difference, Δ⍴, defined as

where ⍴ads-sub, ⍴sub, and ⍴ads denote the charge densities of the adsorbate on the substrate, substrate, and adsorbate, respectively. The charge density difference of the HB sheet with its corresponding slice position is presented in Fig. 6. In the pristine HB sheet–water interaction, charge redistribution was observed (Fig. 6a), which induced a dipole in the HB sheet and further polarized the O–H bond in water, resulting in a complimentary negatively charged region in the B atom of the HB sheet and a positively charged region in the H atom of water. In the case of H-vacant HB sheet, a negatively charged region was formed in the H-vacancy region, which attracts the positively charged H atom of water, as shown in Fig. 6b. Due to the lack of a B atom, the H atom of B-vacant HB sheet closest to the water molecule created a negatively charged region toward the water in the B-vacant HB sheet–water interaction (Fig. 6c), in contrast to the pristine HB sheet case. The calculated Δ⍴ results indicate that the interaction between the HB sheets and water is of the electrostatic type, in addition to the vdW type. Note the fact that the electron being accumulated in the vicinity of the B atom upon adsorption of the water molecule does not necessarily explain the charge state of the B atom nor its reactivity.

Charge density difference Δρ (right) and corresponding slice position (left) of water-adsorbed on (a) pristine, (b) H-vacant, and (c) B-vacant HB sheet. Red (blue) indicates electron accumulation (depletion). The low/high saturation limit for (a), (b), (c) are ±0.014, ±0.027, and ±0.027 e Å−3, respectively.

Löwdin population analysis of HB sheets and diborane

To further explore the electronic states of the HB sheets, we conducted a Löwdin population analysis to calculate the atomic charges (Table 3). We found that the B atom of a pristine HB sheet is negatively charged (3.14 e), with its number slightly higher than its total valency (3 e). The negatively charged B atom of the pristine HB sheet agrees well with the experimental observation of the negatively charged B atom in XPS, as mentioned above. This finding further explains the attraction of the H atom of water to the B atom of the pristine HB sheet. If the B atom is positively charged, then the O atom of water should be the one closest to the B atom of the HB sheet. However, the H atom of water is oriented toward B, indicating that the B atom is negatively charged. In Ref. 11, the B atom in HB is suggested to be positively charged based on Bader charge analysis. We also performed Bader charge analysis and obtained similar results (see Supplementary Table 2). However, this result cannot explain the trend observed in the XPS measurements and the adsorption state of water, in which one of the O–H bonds of water points to a B atom. We also performed Löwdin population analysis of MgB2 and B(OH)3 and found that B atoms are negatively and positively charged, respectively, a trend consistent with the XPS observations (Supplementary Table 3). Thus, we concluded that Löwdin population analysis is more suitable for the current system and that B atoms in a pristine HB sheet are negatively charged.

The negatively charged character of the B atoms may be understood by the analogy with B2H626,27,28. BH3, a constituent molecule of B2H6 is purely electrophilic in its planar ground state. However, the deformation of BH3 fragments to the non-planar configuration makes their highest occupied MOs active and develop an electron donor character, alongside the acceptor characteristic of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital, forming 3-center-2-electron (3c-2e) B–H–B bonds29. This condition applies to the HB sheet in which the non-planar B–H–B bonds are formed.

In the case of the H-vacant HB sheet, the B atom is less negatively charged (3.03 e) compared with the pristine one, presumably due to the less electron donation from the center H. The case of the B-vacant HB sheet provides a more complex but interesting perspective on water dissociation. The B atom nearest to the H atom of water is negatively charged (3.52 e), but that nearest to the O atom of water is positively charged (2.94 e), the latter being similar to the B atom in borane (BH3). In the hydrolysis reaction, the formation of B(OH)3 requires the attachment of (OH)– of water to the B atom. In the case of the HB sheet, the attachment of the O atom of water rarely occurs, and thus, the hydrolysis reaction does not proceed. In the case of B2H6, the negatively charged B atom (Table 3) also suggests that B2H6 has a similar adsorption phenomenon to that of the HB sheet. In fact, a first principles molecular dynamics simulation of B2H6 in water by Pietro et al.30 reported that the H atom of water is closer to a B atom of B2H6. We conducted a charge analysis of a dissociated B2H6 or BH3 and found that the B atom of BH3 was positively charged (Table 3), suggesting that the dissociation of B2H6 induces a change in charge polarity. In the case of BH3, the attachment of an O atom of water is now possible due to the positively charged B, indicating that the dissociation of B2H6 and hence the formation of a positively charged B is an enabling step in the discussed hydrolysis. This finding also suggests that the HB sheets can undergo hydrolysis when a positively charged B atom is created by the formation of a B vacancy in the bulk or at the edge. However, considering the relatively large B vacancy formation energy, the probability of this event is considerably low. This factor may explain the partial hydrolysis reaction observed in the experiment shown in Fig. 1a.

Bonding analysis

Finally, to gain further insights into the bonding nature of the HB sheets, we calculated the maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWFs) of HB sheet and B2H6 (Fig. 7). We obtained MLWFs and the corresponding Wannier function centers (not shown) at the B–B bonds, indicating the covalent bonding between B atoms. The stability of the HB sheet can be attributed to the B–B bond (Fig. 7a), which is further stabilized by forming the B–B bond network within the sheet, unlike the H–B bonds of B2H6 at the edge (see the corresponding MLWF in Fig. 7c). We suppose that if a B-terminated edge is formed in the HB sheet, which is not supported by the B–B bond network, it may be susceptible to dissociation, like B2H6, and the edges can be a cause of the partial hydrolysis observed in the experiment. While the calculated MLWFs of the 3c–2e bond of B2H6 (Fig. 7d) agree well with the classical view31, the MLWF of the 3c–2e bond of HB sheet (Fig. 7b) shows contrasting characteristics. In the case of B2H6, only occupied orbitals contribute to the MLWF, whereas in the case of the HB sheet, unoccupied states are also included to construct the MLWFs because of the metallic nature of the HB sheet. This factor could be the main reason for the difference in the MLWFs of the two cases. The contribution of the unoccupied states also suggests that the B–H–B bonding mechanism of the HB sheet is different from the conventional 3c–2e bond in boron hydrides. Likewise, the different B–H–B bonding mechanism of HB sheet and boron hydrides are partly responsible for the difference in chemical stability. We also performed calculations of KB3H8, a crystal composed of a stable B3H8− unit, which is shown to be stable in water32. We obtained MLWFs for the terminal H and 3c–2e bond of B3H8−, similar to B2H6, as well as that for the B–B bond (see Supplementary Fig. 8). The latter MLWF is similar to that of the B–B bond of the HB sheet, and further supports our conclusion that the B–B bond network stabilize the HB sheet.

Conclusion

We have experimentally shown the chemical stability of HB sheets against water. The hydrolysis reaction, which is typical in boron hydrides, largely did not occur when the HB sheets were mixed with water. In addition, the HB sheets–water solution can be dried without damaging the HB sheets. This finding shows that the HB sheets can be reversibly wetted or dried without significant damage to the sample. On the other hand, we found that proton exchange with HB occurs in water with the estimated pKa of 3.5 ± 0.2, even after reactive sites for the hydrolysis reaction are terminated. Thus, for the practical application, one should keep in mind that HB sheets have a chemical stability against hydrolysis reaction, but become acidic in the presence of water.

We also studied the HB sheet–water interaction at the atomic scale by using DFT calculations. The results show that pristine, H-vacant, and B-vacant HB sheets have a very weak interaction with water, which can be referred to as a vdW-type interaction. The hydrolysis reaction did not proceed for the HB sheets because of the negatively charged B, which prevented the attraction of the O atom of water. We investigated the electronic structure and bonding nature of the HB sheets and concluded that the strong covalent B–B bond network mainly explains the distinct stability of the HB sheets. We anticipate that the current study will help the development of HB sheet-based devices.

Methods

Materials

HB sheets were prepared as reported previously14. Specifically, MgB2 powder (60 mg, 99%, Rare Metallic Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was added to 200 mL of acetonitrile (99.5%, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan) or methanol (99.8%, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan), followed by ultrasonication for 30 min. The prepared suspension was then added to another acetonitrile (or methanol) suspension (100 mL) containing the sulfur-containing ion-exchange resin (30 mL, Amberlite IR120B hydrogen form, Organo Corp., Tokyo, Japan) under nitrogen at room temperature (~298 K). After being stirred (250 rpm) for 3 days, the supernatant or filtrate was filtered through a 1.0 or 0.2 μm pore filter (Omnipore Membrane Filters, Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA) and evaporated on an oil bath at 343 K under nitrogen, to yield the product as a yellow powder.

Reaction with water

HB sheets were mixed with distilled water at room temperature (~298 K). The volume of gas generated was measured by collecting it over water. The collected gas was frequently sampled and analyzed using a gas chromatograph (GC-8A, Shimadzu Corporation, Ltd., Kyoto, Japan), equipped with Molecular Sieves 5 A (60−80 mesh, GL Sciences, Inc.) and a Porapak Q (50−80 mesh, Waters Chromatography Ireland Ltd.) column. Independently, the variation in pH of the aqueous solution was measured using a pH meter (HI 2002-01, HANNA Instruments Japan Ltd.).

XPS measurements

XPS measurements were conducted at room temperature (~298 K) using a JPS 9010 TR (JEOL, Ltd., Japan) with an ultrahigh vacuum chamber and an Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV). The pass energy was 10 eV, the energy resolution (estimated from the Ag 3d5/2 peak width of a clean Ag sample) was 0.635 eV, and the uncertainty in the binding energy was ±0.05 eV. The sample was placed on the sample holder with graphite tape and introduced to an ultrahigh vacuum chamber for measurement. The Shirley background was subtracted from the spectrum using SpecSurf software (version 1.8.3.7, JEOL, Ltd., Japan). The charge buildup in the sample caused higher binding energy shifts for those spectra. Thus, we calibrated the charge-up amount based on the C1s peak of graphite tale as to be 284.6 eV.

FTIR measurements

Infrared spectra were acquired using a Bruker Alpha spectrometer augmented with a diamond attenuated total reflection setup in a N2 glovebox.

Mass analysis

Mass analyses were conducted by a home-build mass spectrometer system. The gas was injected in the system by syringe with 1.0 mL, where the gas was introduced in the ultrahigh vacuum chamber via the differential pumping system, and analyzed by the quadrupole mass spectrometer (ANELVA Quadrupole mass spectrometer M-200QA, CANON ANELVA CORPORATION Ltd.) after passing through the capillary tube (Fused Silica Inertness Tubings, GL Science Inc.).

Computational details

Structural optimization and electronic structure calculations were performed under the framework of DFT as implemented in Quantum Espresso33,34 with GBRV ultrasoft pseudopotentials35,36. The plane-wave basis set was used to expand the wavefunction and augmentation charge density with cutoff energies of 60 and 480 Ry, respectively. Pseudopotentials are based on the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) formulation of GGA37. To account for the vdW forces, rev-vdW-DF2 exchange-correlation functionals were mainly used alongside PBE38,39,40,41,42. We examined different vdW inclusive density functionals and found that the calculated adsorption energies and geometries were similar regardless of the functional used (see Supplementary Fig. 9). Monkhorst-Pack k-point meshes43 of 4 × 4 and 16 × 16 were employed for the Brillouin zone integration in the structural optimization and DOS calculations, respectively. Lattice and ionic minimizations used the force and energy convergence criteria of 10−4 Ry Bohr−1 and 10−5 Ry, respectively. A (4 × 4) supercell was adopted for the water adsorption calculations. With the use of the periodic boundary condition (PBC), the surface was infinitely projected along the x-, y-, and z-axes, thus simulating an infinite surface along the x–y plane. A vacuum spacing of ~15 Å was used to separate the repetition along the z-axis. This model imitates the center of an HB flake where edge effects are negligible. We confirmed that the artificial electrostatic interaction with the image sheets due to PBC is negligible by performing the calculations with an effective screening medium method44,45. MLWFs were generated using Wannier9046,47,48.

Data availability

The optimized structures of the bare and the water-adsorbed pristine, H-vacant, and B-vacant HB sheets obtained in the XCrySDen49 structure format, as well as the corresponding input files for Quantum Espresso33,34 are available on the Materials Cloud Archive50. Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Wu, X. et al. Two-dimensional boron monolayer sheets. ACS Nano 6, 7443–7453 (2012).

Penev, E. S., Bhowmick, S., Sadrzadeh, A. & Yakobson B. I. Polymorphism of Two-Dimensional Boron. Nano Lett. 12, 2441–2445 (2012).

Feng, B. et al. Dirac Fermions in Borophene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 096401 (2017).

Lau, K. C. & Pandey, R. Stability and electronic properties of atomistically-engineered 2D boron sheets. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 2906–2912 (2007).

Piazza, Z. A. et al. Planar hexagonal B36 as a potential basis for extended single-atom layer boron sheets. Nat. Commun. 5, 3113 (2014).

Li, W.-L. et al. The B35 cluster with a double-hexagonal vacancy: a new and more flexible structural motif for borophene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 12257–12260 (2014).

Mannix, A. J. et al. Synthesis of borophenes: anisotropic, two-dimensional boron polymorphs. Science 350, 1513–1516 (2015).

Zhang, Z. et al. Substrate-Induced Nanoscale Undulations of Borophene on Silver. Nano Lett. 16, 6622–6627 (2016).

Feng, B. et al. Experimental realization of two-dimensional boron sheets. Nat. Chem. 8, 563–568 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Experimental realization of honeycomb borophene. Sci. Bull. 63, 282–286 (2018).

Shao, L. et al. A theoretical study of several fully hydrogenated borophenes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 7630–7634 (2019).

Chen, X.-M. & Chen, X. Chemical Syntheses of Two-Dimensional Boron Materials. Chem 6, 324–326 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Synthesis of borophane polymorphs through hydrogenation of borophene. Science 371, 1143–1148 (2021).

Nishino, H. et al. Formation and characterization of hydrogen boride sheets derived from MgB2 by cation exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13761–13769 (2017).

Tateishi, I. et al. Semimetallicity of free-standing hydrogenated monolayer boron from MgB2. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 024004 (2019).

Abtew, T. A., Shih, B. C., Dev, P., Crespi, V. H. & Zhang, P. Prediction of a multicenter-bonded solid boron hydride for hydrogen storage. Phys. Rev. B 83, 094108 (2011).

Makaremi, M., Mortazavi, B. & Singh, C. V. 2D Hydrogenated graphene-like borophene as a high capacity anode material for improved Li/Na ion batteries: A first principles study. Mater Today Energy 8, 22–28 (2018).

Kawamura, R. et al. Photoinduced hydrogen release from hydrogen boride sheets. Nat. Commun. 10, 4880 (2019).

Labille, J. & Brant, J. Stability of nanoparticles in water. Nanomedicine 5, 985–998 (2010).

Weiss, H. G. & Shapiro, I. Mechanism of the Hydrolysis of Diborane in the Vapor Phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 75, 1221–1224 (1953).

Nishino, H. et al. Formation Mechanism of Boron-Based Nanosheet through the Reaction of MgB2 with Water. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 10587–10593 (2017).

Tominaka, S. et al. Geometrical Frustration of B-H Bonds in Layered Hydrogen Borides Accessible by Soft Chemistry. Chem 6, 406–418 (2020).

Jiao, Y., Ma, F., Bell, J., Bilic, A. & Du, A. Two-Dimensional Boron Hydride Sheets: high Stability, Massless Dirac Fermions, and Excellent Mechanical Properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 10292–10295 (2016).

Wella, S. A., Hamamoto, Y., Suprijadi, S., Morikawa, Y. & Hamada, I. Platinum single-atom adsorption on graphene: a density functional theory study. Nanoscale Adv. 1, 1165–1174 (2019).

Sun, J., Zhang, Y., Leng, J. & Ma, H. The electronic and transport properties of borophane with defects: a first principles study. Phys. E 97, 170–176 (2018).

Lipscomb, W. N. The boranes and their relatives. Science 196, 1047–1055 (1977).

Eberhardt, W. H., Crawford, B. & Lipscomb, W. N. The Valence Structure of the Boron Hydrides. J. Chem. Phys. 22, 989 (1954).

Hoffmann, R. & Lipscomb, W. N. Boron hydrides: LCAO-MO and resonance studies. J. Chem. Phys. 37, 2872 (1962).

Yamabe, S., Minato, T., Fujimoto, H. & Fukui, K. An MO study of bridge bonds in B2H6. Theoret. Chim. Acta 32, 187–201 (1974).

Di Pietro, E., Cardini, G. & Schettino, V. Ab initio molecular dynamics study of the hydrolysis reaction of diborane. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 9, 3857–3863 (2007).

Melichar, P., Hnyk, D. & Fanfrlík, J. A systematic examination of classical and multi-center bonding in heteroborane clusters. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 20, 4666–4675 (2018).

Chen, X.-M. et al. Facile Synthesis of Unsolvated Alkali Metal Octahydrotriborate Salts MB3H8 (M=K, Rb, and Cs), Mechanisms of Formation, and the Crystal Structure of KB3H8. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2720–2724 (2019).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Vanderbilt, D. Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys. Rev. B 41, 7892 (R) (1990).

Garrity, K. F., Bennett, J. W., Rabe, K. M. & Vanderbilt, D. Pseudopotentials for high-throughput DFT calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 81, 446–452 (2014).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Hamada, I. Van der Waals density functional made accurate. Phys. Rev. B 89, 121103(R) (2014).

Hamamoto, Y., Hamada, I., Inagaki, K. & Morikawa, Y. Self-consistent van der Waals density functional study of benzene adsorption on Si(100). Phys. Rev. B 93, 245440 (2016).

Callsen, M. & Hamada, I. Assessing the accuracy of the van der Waals density functionals for rare-gas and small molecular systems. Phys. Rev. B 91, 195103 (2015).

Sabatini, R., Küçükbenli, E., Kolb, B., Thonhauser, T., & De Gironcoli, S. Structural evolution of amino acid crystals under stress from a non-empirical density functional. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 24, 424209 (2012).

Thonhauser, T. et al. Van der Waals density functional: self-consistent potential and the nature of the van der Waals bond. Phys. Rev. B 76, 125112 (2007).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188 (1976).

Otani, M. & Sugino, O. First-principles calculations of charged surfaces and interfaces: a plane-wave nonrepeated slab approach. Phys. Rev. B 73, 115407 (2006).

Hamada, I., Otani, M., Sugino, O. & Morikawa, Y. Green’s function method for elimination of the spurious multipole interaction in the surface/interface slab model. Phys. Rev. B 80, 165411 (2009).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. wannier90: a tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 178, 685–699 (2008).

Pizzi, G. et al. Wannier90 as a community code: new features and applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 165902 (2020).

Marzari, N., Mostofi, A. A., Yates, J. R., Souza, I. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized Wannier functions: theory and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 1419 (2012).

Kokalj, A. XCrySDen-a new program for displaying crystalline structures and electron densities. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 17, 176–179 (1999).

Rojas, K. I. M. et al. Chemical stability of hydrogen boride nanosheets in water. Materials Cloud Archive 2021.87 https://doi.org/10.24435/materialscloud:40-28 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Nos. JP18K18989, JP19H02551, JP19H05046, JP18H05519, JP20H02569, and JP21H00015), MEXT Element Strategy Initiative to Form Core Research Center (Grant No. JPMXP0112101001) and for Catalysts and Batteries (Grant No. JPMXP0112101003), KUMAGAI, Ogasawara, and Samco foundations for the Promotion of Science & Engineering, and MHI Innovation Accelerator LLC. We would like to acknowledge the financial support from the Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO), the Tokyo Electron Ltd., and the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) of the Philippines through ASTHRDP. Some of the calculations were performed using the facilities of the Supercomputer Center, Institute for Solid State Physics, University of Tokyo, and the Numerical Materials Simulator at National Institute for Materials Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.H. and T.K. designed the research. K.I.M.R. and I.H. performed the DFT calculations. H.N., R.I., S.I., M.M., and T.K. performed the experiments. N.T.C., Y.F., S.O., N.B.A., and Y.M. contributed to the analysis of DFT calculations. K.I.M.R., T.K., and I.H. wrote the paper with inputs from S.T. and H.H. and Y.M. All authors discussed the data and contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Communications Materials thanks Xuenian Chen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Reinhard Maurer and Aldo Isidori. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rojas, K.I.M., Cuong, N.T., Nishino, H. et al. Chemical stability of hydrogen boride nanosheets in water. Commun Mater 2, 81 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-021-00184-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-021-00184-5

This article is cited by

-

Hydrogenated borophene enabled synthesis of multielement intermetallic catalysts

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Carbon dioxide adsorption and conversion to methane and ethane on hydrogen boride sheets

Communications Chemistry (2022)