Abstract

Two-dimensional lead halide perovskites have demonstrated their potential as high-performance scintillators for X- and gamma-ray detection, while also being low-cost. Here we adopt lithium chemical doping in two-dimensional phenethylammonium lead bromide (PEA)2PbBr4 perovskite crystals to improve the properties and add functionalities with other radiation detections. Li doping is confirmed by X-ray photoemission spectroscopy and the scintillation mechanisms are explored via temperature dependent X-ray and thermoluminescence measurements. Our 1:1 Li-doped (PEA)2PbBr4 demonstrates a fast decay time of 11 ns (80%), a clear photopeak with an energy resolution of 12.4%, and a scintillation yield of 11,000 photons per MeV under 662 keV gamma-ray radiation. Additionally, our Li-doped crystal shows a clear alpha particle/gamma-ray discrimination and promising thermal neutron detection through 6Li enrichment. X-ray imaging pictures with (PEA)2PbBr4 are also presented. All results demonstrate the potential of Li-doped (PEA)2PbBr4 as a versatile scintillator covering a wide radiation energy range for various applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The research on lead halide perovskite (referred to here as ‘perovskite’) for X-ray or gamma-ray detection has been rapidly expanding. On one hand, employing methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) as the active material in a solar cell configuration shows good performance in X-ray photon to electron conversion1,2,3,4. On the other hand, the idea of a perovskite scintillator emerged as early as 2008 but did not receive much attention until the wide application of perovskite in high-energy radiation detection5. The former detection is direct and straightforward with simple conversion photons to electrons. However, to efficiently extract the free carriers, other transport layers are required, and the perovskite absorber layer requires to be thin which makes the device complicated to fabricate and less efficient to absorb X-ray photons. Compared with the former, scintillation detection requires only the scintillator crystal and integrated visible light detection hardware like charge-coupled devices or complementary metal-oxide-semiconductors, which are commercially available and low cost. There is a great demand in the scintillator market for medical imaging, scientific research and security, and new challenges makes the research still very active6,7. Current commercial scintillators are bulk crystals and their synthesis usually require temperature ranging from 621 °C for CsI:Tl up to more than 2000 °C for Lu2SiO5:Ce3+ (LSO) using Bridgman or Czochralski growth8. The huge energy consumption to generate and maintain such high temperatures hinders the reduction of production costs.

The intrinsic heavy atom Pb in perovskite and the possibility of low-temperature and solution-processing fabrication allow perovskite to be a candidate for next generation scintillator. Besides, it is reported that the organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite demonstrates a good radiation stability under gamma-ray at least compared with inorganic glass9. In terms of crystal structure, perovskites can be classified as three-dimensional (3D) and two-dimensional (2D). It is generally believed that 2D ones have higher light yield and faster decay due to their higher exciton binding energy (hundreds of meV) compared with 3D ones (tens of meV)10,11. High-energy alpha particle detection and the potential X-ray imaging applications with 2D perovskite single-crystal scintillators have never been reported. We note that recently 3D perovskite CsPbBr3 nanocrystals12 and nanosheet13 have demonstrated good performance as scintillator screen in X-ray imaging. However, the inherent chemical instability and low density of composite made of nanomaterials (inadequate radiation stopping) is an obstacle in practical applications where low doses are required. 2D bulk crystals in this scenario could be another option because they possess the benefits mentioned above and they are free from such disadvantages. Doping could be a useful approach to modify or boost some scintillator performance14. Li dopant has been reported for modification of optical properties15 and reduction of nonradiative loss in perovskite exciton recombination16. Electrochemical doping of Li was achieved to lower the threshold voltage for perovskite LED17. The introduction of 6Li can bring a completely new functionality, thermal neutron detection because of the intrinsic high thermal neutron capture of 6Li isotope18. Thermal neutron detection plays an important role in neutron scattering research18, landmine detection19, and oil logging20. However, current thermal neutron scintillators also suffer from the high cost of the high-temperature processing. A recent report of the 2D semiconductor 6LiInP2Se6 for first-time direct thermal neutron detection provided a new direction, but this direct detection mode is still far from commercialization and wide application for neutron imaging21. It will be of interest to combine the merits of 2D perovskite and Li dopant to develop low-cost X-/gamma-ray scintillators with extra thermal neutron detection capability, and investigate the properties changes or develop new scintillator behaviors.

In this work, we synthesized Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 perovskite crystals which are characterized under different types of radiation. We also tested its capability to discriminate between gamma-ray and alpha particle. Finally, we demonstrate the employment of our perovskite in X-ray imaging. After temperature-dependent X-ray luminescence and X-ray thermoluminescence characterizations, it is concluded that Li ions being trapped in the crystal pose their impact on enhancing while broadening the emission. Under 662 keV gamma-ray, the light yield of Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 is up to 11,000 photons per MeV (ph per MeV) with a fast-primary decay time of 11 ns. Successful detection of alpha particle, in conjunction with reasonable discrimination between gamma ray and alpha particle, demonstrates the potential of Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 crystal in neutron detection. With 8 keV soft X-ray, X-ray phase-contrast images were obtained using our perovskite as the scintillator screen. Our study suggests the potential of Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 as a versatile scintillator in wide-range energy radiation detection.

Results and discussion

Crystal structure and Li-doping characterizations

Compared with 3D perovskite, the layered structure of (PEA)2PbBr4 introduces the quantum confinement effect11. In this case, large binding energy (hundreds of meV versus tens of meV in the 3D counterpart) favors excitonic recombination and thus theoretically enhances luminescence22. The key to transforming a 3D lead halide perovskite into a 2D one is the introduction of a long alkyl chain or bulky organic cation, such as n-butylammonium, 2,2′-(ethylenedioxy)bis(ethylammonium)23, and 3,4,5-Trifluoroaniline ammonium24. In our experiment, the phenethylammonium cation is chosen due to its high chemical stability, commercial availability, and fast scintillation5,25. The structure of (PEA)2PbBr4 is shown in Fig. 1a. The alternating inorganic/organic layers effectively confine the exciton inside the inorganic layer and thus benefit the scintillation under high-energy radiation like gamma-ray25. Figure 1b shows the optical images of the 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 crystals. The size of the tilted hexagonal-shape crystal can be up to 1 × 0.7 × 0.2 cm3 due to the slow evaporation method. Although some grains and boundaries exist, the transparency is still satisfactory as all the assigned letters below the crystal can be seen clearly. Under UV (365 nm) and X-ray (Cu Kα, 8 keV) excitation, the crystal shows a bright purple-blue emission which indicates high crystal quality. Our blue emission brightness is comparable to that of recent 1D Rb2CuBr3 under 30 keV X-ray radiation26. The powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) result is demonstrated in Fig. 1c. The experimental XRD pattern is comparable to the powder diffraction pattern simulation from the corresponding crystallographic information file (Supplementary Fig. 1)27. No substantial peak shift can be found except a slight intensity ratio of the (020) peak at 15.4° and the (003) peak at 15.9° decreases from undoped to highest 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 crystals. The absence of large difference in XRD implies Li dopant induced little lattice distortion. There are two reasons behind this observation. On one hand, Li is a light element and its X-ray cross section is smaller than the other elements. On the other hand, Li atom is so small that it is unlikely to cause large lattice distortion while the Li concentration is relatively low in the crystal, which is confirmed by the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICPMS) results demonstrated in Fig. 1d (see also Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1). In our experiment, we used (PEA)2PbBr4 crystals with different Li-doping concentrations at comparable size and thickness, allowing us to make direct qualitative and quantitative comparisons. As the Li/Pb precursor ratio increases, the Li/Pb XPS integrated intensity ratio from the crystals rises from undoped to 1:100 and then gradually reaches a plateau. According to integration of different elements, we estimate that the Li/Pb ratio is 5% in the highest doping 1:1 Li-doped crystal. ICPMS suggests also a similar 4% Li/Pb ratio in the highest doped 1:1 crystal but they are variations in 1:100 and 1:10 crystals compared with XPS result. The differences can be attributed to different element detection sensitivity because of varied detection mechanisms, but we consider that they are still reasonable, because the absolute differences are not large as well as the low concentration and intrinsic light atom properties of Li may cause insensitivity in these characterizations. The natural abundance of 6Li, of interest for thermal neutron capture is 7.59%, and thus the 6Li percentage is around 0.38% in 1:1 Li-doped crystal using the 5% Li/Pb XPS ratio. In our experiment, while we increased the Li/Pb ratio exponentially in the precursor solutions, the Li/Pb ratio in the corresponding crystals increased only marginally. We suggest that it is difficult to control the actual Li-doping level as we expected by simply adding more dopant precursor.

Temperature-dependent X-ray luminescence

Based on the above XPS and ICPMS results, the existence of Li dopant within the perovskite is verified. Therefore, we proceed to investigate the influence of Li in temperature-dependent X-ray luminescence (XL) spectra. Here the undoped and the 1:1 Li-doped crystals are chosen and compared because their representative emission contrast is quite distinctive under X-ray excitation. Figure 2a, b shows the XL comparison between two representative high and low temperatures (330 and 10 K) from undoped and 1:1 Li-doped crystals (1:100 and 1:10 in Supplementary Fig. 3). Both free exciton (FE) emissions at 418 nm are shifted to 436 nm from 10 to 330 K28. XL spectra at 10 K from both crystals show a bump ranging from 450 to 750 nm. We consider this bump corresponds to the self-trapped exciton (STE) emissions although STE in (001) type 2D perovskite are scattered. There are two reasons we attribute the broad peaks at low temperature to STE. First, STE in (001) type can be temperature-dependent in which STE only emerges at low temperature29, and that is what we observed in the spectra. Second, dopant in 2D perovskite could possibly trigger the occurrence of STE30. However, the intensity ratio between FE emission and the STE emission (denoted as FE/STE ratio) is much higher in a 1:1 crystal than in undoped one. Theoretically, higher Li concentration should create more traps and thus more likely to have stronger STE emission. In fact, Li being traps is indeed confirmed by the following X-ray excited thermoluminescence (TL) measurements. In this case, Li dopant could bring three possible effect on FE and STE quenching or enhancement at 10 K. The first possibility is Li dopants enhance both FE and STE but impose stronger effect on FE. The second possibility is Li dopants quench both FE and STE but have stronger effect on STE. The final possibility is Li dopant enhances FE while quench STE. Supplementary Fig. 4 demonstrates that all doped crystals have higher intensity than undoped ones at 10 K, so it is unlikely for Li dopant to quench both FE and STE. Then we can compare the normalized 2D map temperature-dependent XL of undoped and 1:1 Li-doped crystals in Fig. 2c, d (1:100 and 1:10 in Supplementary Fig. 5). We can see the bump in from 1:1 crystal survives up to 200 K and thus Li dopant does not quench STE. Our first proposition of Li dopant may enhance both FE and STE seems more suitable to our observations. The emission peaks at 330 K are asymmetric, which we believe it is due to part of the emission being re-absorbed and confirmed by the UV absorption and emission spectrum (see Supplementary Fig. 6) since the X-ray luminescence shares a similar exciton emission mechanism to the UV photoluminescence. The emission peak is shifted from 405 nm in PL to 436 nm in XL. This redshift behavior also occurs for three-dimensional CsPbBr3 perovskite single crystal. In addition, we can find the full width half maximum (FWHM) of undoped is smaller than that of 1:1. By comparison of this series of crystals, FWHM at 330 K increases gradually from undoped to 1:1 (undoped: 30 nm, 1:100 doped: 41 nm, 1:10 doped: 46 nm, and 1:1 doped: 50 nm). The effect of Li is apparent in broadening the emission, besides enhancing the emission intensity. In Fig. 2c, d, from 200 to 10 K both emission peaks are narrow and almost symmetric and STE emissions exist. But the difference in peak position or FWHM is quite small between undoped and doped due to strong narrowing effect by lowering temperature31. Figure 2e plots the quantitative comparison of FWHM evolution upon cooling. No substantial variation can be seen below 200 K and above 200 K, the slope starts differing as a result of Li dopant. A simple linear fitting can be employed to quantify the difference. The slope values increase considerably from undoped to 1:1 but level off (undoped: 0.15, 1:100 doped: 0.24, 1:10 doped: 0.25, and 1:1 doped: 0.28, unit, nm per K) and such behavior agrees well with the integrated ratio profile in XPS analysis in Fig. 1d.

X-ray luminescence spectra at representative temperature, 10 and 330 K from a undoped and b 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4. Temperature-dependent X-ray luminescence spectra from 10 and 350 K from c undoped and d 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4. e Comparison of FWHM versus temperature among different Li-doped crystals. f Comparison of the negative thermal quenching behavior.

The more interesting part of the 2D maps is the stronger emission upon higher temperature, as shown in Fig. 2f. Such behavior has been reported earlier in photoluminescence (PL) of n-type GaAs and n-type ZnS and it was termed as the negative thermal quenching effect32. This effect is commonly originated from thermally excited traps32. A similar phenomenon in temperature-dependent PL of (PEA)2PbBr4 microplate was observed33. Negative thermal quenching is almost the opposite to the thermal quenching in our previous report on methylammonium lead halide perovskite single crystals using the same setup, where the emissions become stronger monotonically as temperature goes down to 10 K31. In this scenario, the strongest emission occurrs at 350 K, the highest temperature in this experiment. As cooling continues, the emissions reach their minima at around 220–200 K. Below 200 K, slowly the emissions become slightly stronger compared with their minima and the STE emissions begin to appear. This effect is enhanced with Li doping. The curves of Li-doped crystals are “lifted up” compared with the undoped one. The integrated intensity ratios between the minima and the maxima (~350 K) can be a parameter to define the enhancement induced by Li. Other parameters of the negative thermal quenching fits are presented on Supplementary Table 2 (see Supplementary Discussion 1 for details). With increasing Li concentration, this ratio increases from lowest undoped to highest 1:1 doped (undoped: 0.23, 1:100 doped: 0.25, 1:10 doped: 0.32, and 1:1 doped: 0.42). Although the magnitude of the enhancement is small, it indicates the relative wide-range emission stability of our Li-(PEA)2PbBr4. The strongest emission is rarely above 300 K in lead halide perovskite because thermal quenching dominates and prevents excitonic recombination at that temperature. It is reported that most of the strongest emission from materials with negative thermal quenching behavior occurs at around 100–200 K for typical II–VI or III–V semiconductor composites32; while it is considerably lower than 300 K for other 3D perovskites or perovskite nanocrystals/quantum dots without extra protection33,34,35. Such stronger emission upon higher temperature characteristics allows (PEA)2PbBr4-based detectors to operate at up to 350 K or even higher. The continuous luminescence change suggests the absence of temperature-induced phase transition36. Instead of making it worse upon rising temperature, the addition of Li dopant increases the stability of the intensity or the radiation-converted photons with the temperature. Beside the later function of Li dopant with other radiation detection, the addition of concentration already makes Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 even more competitive compared with the other perovskites mentioned above (3D or nanocrystals) since the Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 scintillator performs well at a wide range of temperatures, and no extra cooling is required to maximize its emission and light yield.

X-ray excited thermoluminescence and afterglow

After a detailed discussion on the emission properties of Li-(PEA)2PbBr4, we continue presenting an insight on the role of Li as trap agent using X-ray excited TL characterization. Figure 3a demonstrates the comparison of normalized TL curves. After 10 min X-ray exposure at 10 K, the emission was monitored for 100 min. We find two changes induced by Li doping. The most prominent change is that the thermoluminescence peaks (after 3600 s) become more intense upon higher Li doping. To analyze these TL peaks, the classic Randall–Wilkins equation37 can be employed to deconvolute the peaks:

where I is the TL intensity, 3 is the number of deconvoluted peaks, n0i is the initial trap concentration, si is the frequency factor, Ei is the trap depth, kB is the Boltzmann constant, β is the heating rate, T is the temperature, and T0 is the initial temperature. The TL peaks of the undoped samples do not exhibit any appreciable fitting. For the other crystals, the TL peaks can be deconvoluted into three peaks and the parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Figure 3b displays the concentration of three types of trap with different energy depths. It is clear that there are more traps at different energy depths with higher Li doping from 1:100 to 1:1. The total number of traps is comparable to the reported value from by photocurrent measurements (105 ~ 107 cm−3)3. Shallow traps (10.8 meV) are the major contribution to the total increase of traps induced by Li doping, while deep traps (124 meV) show a smaller contribution. The other difference is that small after-glow effects can be barely seen in undoped and 1:100 doped crystals, while they become more pronounced in 1:10 and 1:1 (Supplementary Fig. 7). We attribute this behavior to additional traps generated by Li doping. After these characterizations, we establish that Li serves as traps in the (PEA)2PbBr4 scintillation under X-ray irradiation and it may enhance performance while broadening the luminescence.

a X-ray thermoluminescence plots of undoped, 1:100, 1:10, and 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4. The dashed line indicates the rise of temperature. b Initial trap concentration at corresponding energy from 1:100, 1:10, and 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4. For clarity, the symbols of 1:10 and 1:1 are intentionally separated due to their close values.

Gamma-ray pulse height and scintillation decay time

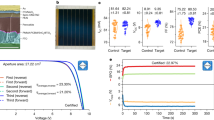

Beside soft X-ray characterization, we further explore scintillation properties under gamma-ray radiation. As temperature-dependent XL shows that the radiation-converted photons are optimized at room temperature, we still need to determine the scintillation light yield. This number is obtained through the comparison of the photopeak signals in the pulse-height spectra at certain energy of gamma-ray radiation with the scintillator single electron response, see the “Methods” section. Figure 4a exhibits the pulse-height spectra of 1:1 crystal with 137Cs (662 keV). The light yield and the energy resolution are 11,000 ± 500 ph per MeV and 12.4%, respectively. For the other doped crystals, the light yield of 1:100 and 1:10 are 6300 ± 300 and 9100 ± 400 ph per MeV, while their energy resolutions are 32.6% and 36.8%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8). The light yield of undoped crystal is 8000 ± 800 ph per MeV. Our light yield values here are determined by traditional gamma-ray pulse-height measurements compared with those estimated by the integral of the X-ray luminescence intensities demonstrated previously for perovskite scintillators12,26. We can see a general tendency of increasing light yield with higher Li concentration although the light yield of undoped is marginally higher than 1:100. We consider that it is due to slightly different crystal quality. Crystal quality, including crystal morphology, transparency and homogeneity plays a critical role on quality-sensitive pulse-height measurement. Unfortunately, crystal quality control is not easy since there is no mature 2D perovskite crystal growth technique from solution method compared with 3D ones38,39. However, it is reasonable that there is no dramatic increase in light yield with more Li since the XPS result manifest close Li concentration in all doped crystals. The energy resolution is also affected by crystal quality. According to our calculation based on Poisson statistics of the photoelectron, the energy resolution of 1:1 crystal can be as low as 6% theoretically40,41,42 (see Supplementary Discussion 2) and hence there is considerable room for energy resolution improvement. The gamma-ray excited decay measurement result of 1:1 is shown in Fig. 4b. A three-component exponential decay was adopted in the fitting. The percentages of decay in this experiment are all in amplitude. The primary (fast) decay time (11 ns) is similar to early reports (9–11 ns)25,38. At this stage, it is difficult to confirm the doping effect on decay time and we tentatively see no significant effect is induced by the Li content since their values are comparable to one another and to other reports (see Supplementary Fig. 9). Compared with the popular commercial NaI:Tl scintillator, the highest light yield of our Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 is lower (11,000 vs. 38,000 ph per MeV), while the primary decay time is one order of magnitude smaller (11 vs. 250 ns) at room temperature8. It indicates that the time density of photons at early stage of the pulse is significantly higher, making Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 advantageous for fast timing applications such as high-speed imaging and image processing applications.

Alpha particle, gamma-ray, and thermal neutron radiation discrimination

In addition to X- and gamma-ray, we took a step further to test our Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 crystals for alpha particle (42α) detection. Figure 5a displays the result of alpha particle pulse-height characterization of 1:1 Li-doped crystal using 241Am (5486 keV) and 244Cm (5805 keV) as the alpha particle sources. Results of other radioisotope sources are also presented in Supplementary Fig. 10. We can easily distinguish the two full-energy peaks although they are relatively broad. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time the successful application of 2D perovskite scintillator in alpha particle detection has been reported43,44,45. The full-energy peaks indicate the potential thermal neutron detection on the alpha particle as a product from the 6Li (n, α) reaction46. Also, there is an opportunity for fast neutron detection by virtue of the considerable amount of hydrogen and Li dopant in the future Li-doped perovskite crystal46. However, the discrimination with other radiations will be more complicated if we add more hydrogen amounts in the crystals. It can be a choice of material for neutron diagnostics in inertial confinement fusion requiring fast neutron detection and back scattering on Li ions47. Figure 5b shows the sign for pulse-shape discrimination (PSD) with our Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 crystal using the optimum filter method48 based on the significant difference between the scintillation decay under alpha particle and gamma-ray excitation (Fig. 5b inset). Alpha particle signals in high-energy channels is quite well separated from gamma-ray ones. However, the alpha particle full-energy peak was broad and the tail at low energy channel is slightly overlapped with the gamma-ray signals. It can be a result of insufficiently high crystal quality and aggravated by the defect layer on the surface of the crystal as the crystal could be degraded through long-time MeV alpha particle bombardment in this measurement. In our previous report of 3D halide perovskite scintillators, dose-dependent XL measurements reveal that radiation dose up to 1 millisievert for one hour has a weak impact on the light yields of bromide perovskite scintillators31. We could reasonably expect a similar X-ray radiation hardness of our (PEA)2PbBr4 crystals and good stability over time at low dose. However, decreases in light yields and energy resolutions in pulse-height spectra were indeed observed after long-time exposure of much higher energetic radiation (see Supplementary Fig. 11). Despite the small signal overlap, the demonstration of PSD discrimination between alpha particle and gamma-ray verifies the potential of thermal neutron detection with our Li-doped 2D perovskite. It is known that thermal neutron detection usually requires the detection of neutron-induced secondary radiation, especially for readily detected charged particles like alpha particle46. However, the process of neutron generation is usually accompanied by gamma-ray background. That is the reason why it is critical to exploit the capability of discriminating between alpha particle and gamma-ray using the PSD method49,50, which is not demonstrated by the recent neutron semiconductor detection21. The quenching factor (α/β ratio), which is determined by the number of photons per MeV produced by one alpha particle over the number of photons per MeV produced by one electron (photoelectric effect by gamma ray in this case), was estimated to be 0.2451. Using this result, we can also discriminate between thermal neutrons and gamma-ray and it is expected that the thermal neutron signal will appear at energy larger than 1.5 MeV. However, as 6Li is only 7.59% in natural abundance21 while the Li content in this crystal is only 5%, it is expected that we cannot observe the strong thermal neutron full-energy peak but only a bump in our experiment as demonstrated in Fig. 5c. In addition, at this current stage, the crystal quality also needs to be improved so that it can compete with the energy resolution of Cs2LiYCl6:Ce3+ crystals52. Besides, the theoretical thermal neutron detection efficiency maximum of natural and 6Li-enriched 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 are 7% and 48%, respectively (see Supplementary Discussion 3 and Supplementary Table 4). The 48% efficiency is still comparable to natural Li-containing elpasolite single-crystal scintillators in an early report53. Therefore, further growth of cm-scale thicker crystals with higher 6Li content are necessary to improve the thermal neutron detection (see Supplementary Fig. 12).

a Alpha particle pulse-height spectra. b Pulse-shape discrimination (PSD) matrix with the shape indicator on y-axis and the measured energy (electron equivalent) on x-axis. The inset with the green and the blue curves shows the normalized average waveforms from both alpha particle and gamma-ray radiation of 137Cs and 241Am sources, respectively. c Pulse-height spectra measured with graphite-moderated Am–Be neutron source of 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 crystal. The pulse-height spectra of neutron and 137Cs sources are indicated by red and blue dots, respectively.

X-ray imaging with Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 scintillator

Finally, to demonstrate the X-ray scintillation imaging application, X-ray phase-contrast imaging of a ubiquitous safety pin was carried out using Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 as a scintillator film. The schematic setup is displayed in Fig. 6a. The safety pin was put inside an envelope as the test subject. The 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 spin-coated film with a thickness of 67 μm (Supplementary Fig. 13) that was prepared by our new technique shows high transparency and satisfying homogeneity, despite some small surface ripples (Fig. 6b). Typical spin-coating and baking techniques were found to be ineffective in acquisition of a homogeneous thick film (up to 50 μm or above for effective X-ray stopping), which is required in the X-ray characterization (see Supplementary Discussion 4)54. To get a thick film, spincoating at low speed (<500 rpm) usually results in an inhomogeneous film. Inspired by a reported spin-coating technique by introducing N2 flow during spincoating, we modified it and blow-dried the film with hot air flow in the last stage of spin-coating55. This technique proved to be very useful and a relatively thick and homogeneous film on glass substrate was obtained. One great merit in (PEA)2PbBr4 should be highlighted here; that is, its intrinsic readiness to form on average mm-size large single-crystal flakes upon drying. It follows that the film is composed of large orientated single-crystal 2D flakes instead of the small un-orientated small crystals which are common in 3D perovskite spin-coated film. The powder XRD verifies the same crystal phase of the spin-coated film as the single crystal (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Longer exposure time (3 s) for the spin-coated film was needed to achieve comparable brightness to the thick crystal in Fig. 1b (~400-μm thickness, 1 s) under X-ray radiation. Despite such circumstances, decent X-ray pictures can be secured as the thickness of 67 μm is enough to stop X-ray radiation, see Supplementary Fig. 14. Due to the substantial difference in X-ray stopping power (Cu Kα, 8 keV) between the envelope and the stainless steel, the fine structure of the safety pin, like a 250-μm slit, is revealed clearly by an ordinary camera as shown in Fig. 6c. Here, the black and white mode was utilized for better contrast. Other items like a spring or a paper clip can be clearly imaged under X-ray as well (Supplementary Fig. 15). Though there are quite a few researches on the scintillation properties of (PEA)2PbBr4 under X-ray or gamma ray25,38, here we demonstrate the first imaging using this perovskite material as far as we know. The quality of the imaging compared with those of CsPbBr312,13 is still lower as our camera is not optimized for the blue emission of the scintillators. Moreover, the configuration of the imaging is different as we did not couple the scintillator directly on the photodetector. However, the convenient coupling of our cost-efficient film with the commercial camera is already applicable in high-throughput security inspection. The film can be even further optimized for a smoother surface and higher thickness in the future and a performance improvement can be expected, such as higher and more homogeneous scintillating brightness and shorter exposure time for reduced noise.

a Scheme of X-ray imaging setup using 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 as scintillator. The safety pin is inside the envelope. b Bright-field image of the safety pin and the Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 film on glass substrate with high transparency. Scale bar is 1 cm. c X-ray image (background corrected) of the safety pin. Black and white mode was applied for better contrast. Scale bar is 5 mm.

In summary, we demonstrated successful Li doping in (PEA)2PbBr4 crystal synthesis using a solution-processing method. Li-dopant serving as traps is capable of enhancing the intensity while broadening the X-ray luminescence. The intrinsic negative thermal quenching behavior of (PEA)2PbBr4 allows it to maintain its scintillating performance at a relatively wide range of temperature; however, with additional Li dopant, the performance stability could be even more improved. We found that Li ion dopant could increase the light yield up to 11,000 ph per MeV while maintain a primary decay time (11 ns) under 662 keV gamma-ray radiation. Good numbers of converted photons and especially significantly fast scintillation response compared with commercial NaI:Tl could be propitious in low-cost and large-size scintillator fabrication. Moreover, we successfully employed our Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 scintillator in alpha particle detection and in discrimination between alpha particle and gamma-ray. Based on the thermal neutron results for crystals doping with natural Li and 6Li, our Li-doped crystal will be a promising thermal neutron scintillator provided more 6Li is included as it is low cost and it can be deposited in large-area arrays of photodetectors. Finally, we carried out low-dose X-ray imaging using high-quality Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 film prepared by our new technique and obtained first satisfactory X-ray imaging pictures using (PEA)2PbBr4 perovskite to our knowledge. Here we show promising characterization results and prove that our Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 scintillator may hold promise as a low-cost and versatile radiation detector covering a wide range of energy from keV up to MeV.

Methods

Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 crystals and film preparation

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, anhydrous), phenethylammonium bromide ((PEA)Br, 98%), lead bromide (PbBr, 98%), and lithium bromide (LiBr, ≥99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Undoped precursor solution was prepared by dissolving equal molar amount of (PEA)Br and PbBr2 in DMSO under stirring at 100 °C for 2 h under N2. Crystals were obtained by evaporating DMSO from 3 M precursor solution in ambient environment slowly; it could take a few weeks. The crystal precipitate was then washed with diethyl ether and dried under vacuum for future characterizations. For Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 crystals, the procedure was the same as that of the undoped one except for the addition of LiBr to the precursor solution. The amount of LiBr depends on the molar ratio between Li and Pb. In our experiment, one undoped and three doping concentration were prepared, i.e., molar ratio Li:Pb = 0, 1:100, 1:10, and 1:1 (denoted as undoped, 1:100, 1:10, and 1:1). The concentration of the precursor solution is 3 M except 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 (2 M due to limited solubility of LiBr). Here, it should be noted that the ratio is from the precursor instead of the final product. For the film preparation, precursor solution (1:1, 2 M concentration for high viscosity) was spin-coated on a UV-ozone treated cover glass substrate with 500 rpm for 60 s (acceleration: 100 rpm per s). In the last 30 s, a heat gun was applied right on top of the film to blow-dry the film with hot air flow. The film was baked at 100 °C on a hot plate for another 20 min.

Structure and composition characterization

The structure was determined by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurement. The XRD measurements were carried out on a Bruker D8 Discover with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å). Step increment and acquisition time were 0.05° and 1 s, respectively. The element composition was determined by X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICPMS) measurement. XPS measurements were performed in an integrated VG ESCA Lab system using an X-ray source of Magnesium Kα with typical excitation energy output of 1254 eV. The entire experiments were carried out in an ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) system with typical base pressure in the range of ~10−10 mbar and the whole acquisition data were taken at room temperature. The impinged spot size on the sample is about 1 mm in diameter. ICPMS samples were prepared by dissolving respective crystals in deionized water (18 MΩ) and the ICPMS equipment model was PerkinElmer ELAN DRC-e.

Temperature-dependent X-ray luminescence measurement

The experiment was carried out in a similar way as our previous one31. A typical setup consisting of an Inel XRG3500 X-ray generator (Cu-anode tube, 45 kV/10 mA), an Acton Research Corporation SpectraPro-500i monochromator (500 nm blazed grating), a Hamamatsu R928 photomultiplier, and an APD Cryogenics Inc. closed-cycle helium cooler with a Lake Shore 330 programmable temperature controller was used to record XL spectra at various temperatures between 10 and 350 K. The measurements were carried out starting at 350 K (unless indicated) and terminating at 10 K to avoid a possible contribution from thermal release of charge carriers to the emission yield.

X-ray thermoluminescence (TL) measurement

The same setup was used as the one in temperature-dependent X-ray luminescence measurement. Prior to the TL runs, the sample was exposed for 10 min to X-ray at about 10 K. The glow curve was recorded up to 350 K at a heating rate of about 0.14 K per s.

Gamma-ray pulse height and excited decay measurement

We used 137Cs (662 KeV) radioisotope for gamma-ray source and various photomultipliers (PMT) (Hamamatsu R2059, Hamamatsu R878, and Photonis XP Series) for detecting the converted photons. To operate the PMT, we applied a voltage between 1.25 and 1.7 kV. The corresponding output signal from PMT is integrated with a charge sensitive pre-amplifier. The output then feeds a spectroscopic amplifier with a shaping time of 2 μs and an analog-to-digital converter (Ortec series). The photoelectron yield was obtained by comparing the position of photopeak to the position of the mean value of the single electron response in pulse high spectra measurements. The actual light yield for the radiation conversion in photons per MeV was obtained after the photoelectron yield was divided by the quantum efficiencies of the PMT. Scintillation decay measurements were performed by the delayed coincidence single photon counting method, originally proposed by Bollinger and Thomas56. A 137Cs radioactive source, two Hamamatsu photomultiplier tubes (R1104 and R928 for “starts” and “stops”, respectively), a Canberra 2145 time-to-amplitude converter, and a TUKAN-8K-USB multichannel analyzer were used.

Alpha particle pulse-height measurement

Four alpha-emitting sources were used: 241Am (5486 keV), 244Cm (5805 keV), 228Th (with progeny 212Po: 8785 keV), 230Th (4687 keV). To perform alpha particle spectroscopy, the crystal was mounted on the window of a Hamamatsu R9880U-20 photomultiplier tube (PMT), with a thin layer of silicone grease to provide optical coupling. This PMT has a fast time response (0.6 ns rise time), a broad spectral sensitivity (230–920 nm), and an 8-mm diameter photocathode sensitive area. The PMT was operated at a voltage of −750 V for these measurements. The PMT anode signal was input directly to a Caen DT5720D digital pulse processing (DPP) unit which integrated the anode charge pulses over a 92 ns gate. Caen’s CoMPASS software was used to control the DPP parameters and accumulate pulse-height (proportional to energy) spectra for each radioactive source. These radioactive sources were positioned (in air) at 2 mm distance from the surface of the crystal. More detail can be found in Supplementary Information.

Pulse-shape discrimination (PSD) between alpha particle and gamma ray

The PSD capability of 1:1 Li-(PEA)2PbBr4 crystal was tested under alpha particle and gamma-ray signals using 137Cs and 241Am source, respectively. The crystal was mounted on a Hamamatsu multiplier tube R6233-100 and covered with several Teflon layers, except a small hole was opened to enable alpha particle irradiation. The PMT anode signal was digitized directly by a fast analog-to-digital converter (FADC400 Notice Korea) with recording length of 2.56 μs for each pulse. A ROOT-based C++ program was used to record data to a Linux-based PC used for further analysis. The optimum filter method was employed for PSD study with detail information can be found in this reference57.

X-ray imaging setup

The X-ray source was PHYWE XR 4.0 expert unit (Cu anode, 35 kV, 1 mA) and the camera was Chameleon CMLN-13S2C (exposure time depends on varied samples, usually 1–3 s). The equipment was placed as shown in the scheme in Fig. 6a. The envelop with the safety pin inside was put at the aperture of the X-ray tube where the uncollimated X-ray came out. The envelop, the perovskite film and the camera were placed as close as possible to reduce light scattering.

Data availability

The data that support the results presented in the paper are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Yakunin, S. et al. Detection of X-ray photons by solution-processed lead halide perovskites. Nat. Photonics 9, 444–449 (2015).

Büchele, P. et al. X-ray imaging with scintillator-sensitized hybrid organic photodetectors. Nat. Photonics 9, 843–848 (2015).

Wei, H. et al. Sensitive X-ray detectors made of methylammonium lead tribromide perovskite single crystals. Nat. Photonics 10, 333–339 (2016).

Yakunin, S. et al. Detection of gamma photons using solution-grown single crystals of hybrid lead halide perovskites. Nat. Photonics 10, 585 (2016).

Kishimoto, S. et al. Subnanosecond time-resolved X-ray measurements using an organic-inorganic perovskite scintillator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 261901 (2008).

Eijk, C. W. E. V. Inorganic scintillators in medical imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 47, R85–R106 (2002).

Dujardin, C. et al. Needs, trends, and advances in inorganic scintillators. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 65, 1977–1997 (2018).

Weber, M. J. Inorganic scintillators: today and tomorrow. J. Lumin. 100, 35–45 (2002).

Yang, S. et al. Organohalide lead perovskites: more stable than glass under gamma-ray radiation. Adv. Mater. 0, 1805547 (2018).

Bokdam, M. et al. Role of polar phonons in the photo excited state of metal halide perovskites. Sci. Rep. 6, 28618 (2016).

Blancon, J. C. et al. Scaling law for excitons in 2D perovskite quantum wells. Nat. Commun. 9, 2254 (2018).

Chen, Q. et al. All-inorganic perovskite nanocrystal scintillators. Nature 561, 83–88 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Metal halide perovskite nanosheet for X-ray high-resolution scintillation imaging screens. ACS Nano 13, 2520–2525 (2019).

Wei, H. et al. Dopant compensation in alloyed CH3NH3PbBr3-xClx perovskite single crystals for gamma-ray spectroscopy. Nat. Mater. 16, 826–833 (2017).

Shakti, N., Devi, C., Patra, A. K., Gupta, P. S. & Kumar, S. Lithium doping and photoluminescence properties of zno nanorods. AIP Adv. 8, 015306 (2018).

Fang, Z., He, H., Gan, L., Li, J. & Ye, Z. Understanding the role of lithium doping in reducing nonradiative loss in lead halide perovskites. Adv. Sci. 5, 1800736 (2018).

Jiang, Q. et al. Electrochemical doping of halide perovskites with ion intercalation. ACS Nano 11, 1073–1079 (2017).

Bollinger, L. M., Thomas, G. E. & Ginther, R. J. Neutron detection with glass scintillators. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 17, 97–116 (1962).

Clifford, E. T. H. et al. A militarily fielded thermal neutron activation sensor for landmine detection. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 579, 418–425 (2007).

Wu, W., Tong, M., Xiao, L. & Wang, J. Porosity sensitivity study of the compensated neutron logging tool. J. Pet. Sci. Eng, 108, 10–13 (2013).

Chica, D. G. et al. Direct thermal neutron detection by the 2D semiconductor 6LiInP2Se6. Nature 577, 346–349 (2020).

Kumar, S. et al. Efficient blue electroluminescence using quantum-confined two-dimensional perovskites. ACS Nano 10, 9720–9729 (2016).

Birowosuto, M. D. et al. X-ray scintillation in lead halide perovskite crystals. Sci. Rep. 6, 37254 (2016).

Jia, G. et al. Super air stable quasi-2D organic-inorganic hybrid perovskites for visible light-emitting diodes. Opt. Express 26, A66–A74 (2018).

Kawano, N. et al. Scintillating organic–inorganic layered perovskite-type compounds and the gamma-ray detection capabilities. Sci. Rep. 7, 14754 (2017).

Yang, B. et al. Lead-free halide Rb2CuBr3 as sensitive X-ray scintillator. Adv. Mater. 31, 1904711 (2019).

Shibuya, K., Koshimizu, M., Nishikido, F., Saito, H. & Kishimoto, S. Poly[bis(phenethylammonium) [dibromidoplumbate(ii)]-di-[μ]-bromido]]. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Crystallogr. Commun. 65, m1323–m1324 (2009).

Peng, B. et al. Bose–einstein oscillators and the excitation mechanism of free excitons in 2D layered organic–inorganic perovskites. RSC Adv. 7, 18366–18373 (2017).

Smith, M. D., Jaffe, A., Dohner, E. R., Lindenberg, A. M. & Karunadasa, H. I. Structural origins of broadband emission from layered Pb–Br hybrid perovskites. Chem. Sci. 8, 4497–4504 (2017).

Yu, J. et al. Broadband extrinsic self-trapped exciton emission in sn-doped 2D lead-halide perovskites. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806385 (2019).

Xie, A. et al. Thermal quenching and dose studies of X-ray luminescence in single crystals of halide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 16265–16273 (2018).

Hajime, S. Negative thermal quenching curves in photoluminescence of solids. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 37, 550 (1998).

Zhai, W. et al. Acetone vapour-assisted growth of 2D single-crystalline organic lead halide perovskite microplates and their temperature-enhanced photoluminescence. RSC Adv. 8, 14527–14531 (2018).

Cui, X. et al. Temperature-dependent electronic properties of inorganic-organic hybrid halide perovskite (CH3NH3PbBr3) single crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 233302 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Temperature-dependent photoluminescence of inorganic perovskite nanocrystal films. RSC Adv. 6, 78311–78316 (2016).

Yangui, A. et al. Optical investigation of broadband white-light emission in self-assembled organic–inorganic perovskite (C6H11NH3)2PbBr4. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 23638–23647 (2015).

Randall, J. T., Wilkins, M. H. F. & Oliphant, M. L. E. Phosphorescence and electron traps II. The interpretation of long-period phosphorescence. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 184, 347–364 (1945).

Eijk, C. W. E. V. et al. Scintillation properties of a crystal of (C6H5(CH2)2NH3)2PbBr4. In 2008 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record 3525–3528 (IEEE, 2008).

Saidaminov, M. I. et al. High-quality bulk hybrid perovskite single crystals within minutes by inverse temperature crystallization. Nat. Commun. 6, 7586 (2015).

de Haas, J. T. M., Dorenbos, P. & van Eijk, C. W. E. Measuring the absolute light yield of scintillators. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 537, 97–100 (2005).

Dorenbos, P., Haas, J. T. M. D. & Eijk, C. W. E. V. Non-proportionality in the scintillation response and the energy resolution obtainable with scintillation crystals. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 42, 2190–2202 (1995).

Birowosuto, M. D. Novel Gamma-ray and Thermal-neutron Scintillators: Search for High-light-yield and Fast-response Materials (IOS Press, 2008).

McCall, K. M. et al. α-particle detection and charge transport characteristics in the A3M2I9 defect perovskites (A = Cs, Rb; M = Bi, Sb). ACS Photonics 5, 3748–3762 (2018).

Mykhaylyk, V. B., Kraus, H. & Saliba, M. Bright and fast scintillation of organolead perovskite MAPbBr3 at low temperatures. Mater. Horiz. 6, 1740–1747 (2019).

He, Y. et al. Perovskite CsPbBr3 single crystal detector for alpha-particle spectroscopy. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 922, 217–221 (2019).

Knoll, G. F. Radiation Detection and Measurement 3rd edn (Wiley, 1989).

Minami, Y. et al. Spectroscopic investigation of praseodymium and cerium Co-doped 20Al(PO3)3-80LiF glass for potential scintillator applications. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 521, 119495 (2019).

Gatti, E. & Martini, F. D. Nuclear Electronics Vol. 2, 265–276 (Brueder Rosenbaum, 1962).

Roush, M. L., Wilson, M. A. & Hornyak, W. F. Pulse shape discrimination. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 31, 112–124 (1964).

Yamazaki, A. et al. Neutron–gamma discrimination based on pulse shape discrimination in a Ce:LiCaAlF6 scintillator. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 652, 435–438 (2011).

Birowosuto, M. D. et al. Thermal-neutron scintillator: Ce3+ activated Rb2LiYBr6. J. Appl. Phys. 101, 066107 (2007).

Guss, P., Stampahar, T., Mukhopadhyay, S., Barzilov, A. & Guckes, A. Scintillation properties of a Cs2LiLa(Br6)90%(Cl6)10%:Ce3+ (CLLBC) crystal. In Radiation Detectors: Systems and Applications XV. Vol. 9215 (SPIE, 2014).

Birowosuto, M. D. et al. Li-based thermal neutron scintillator research; Rb2LiYBr6: Ce3+ and other elpasolites. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 55, 1152–1155 (2008).

NIST. XCOM Calculator, https://www.physics.nist.gov/PhysRefData/Xcom/html/xcom1.html (2010).

Ng, Y. F. et al. Rapid crystallization of all-inorganic CsPbBr3 perovskite for high-brightness light-emitting diodes. ACS Omega 2, 2757–2764 (2017).

Bollinger, L. M. & Thomas, G. E. Measurement of the time dependence of scintillation intensity by a delayed‐coincidence method. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 32, 1044–1050 (1961).

Vuong, P. Q., Kim, H., Park, H., Rooh, G. & Kim, S. Pulse shape discrimination study with Tl2ZrCl6 crystal scintillator. Radiat. Meas. 123, 83–87 (2019).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. Vesta: a three-dimensional visualization system for electronic and structural analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr 41, 653–658 (2008).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. Vesta 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the financial support from Singapore Ministry of Education through AcRF Tier1 grant (MOE2017-T1-002-142). We also thank Dr. Philip Anthony Surman for proof reading and fruitful discussion about the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D.B. and Cuong D. conceived the idea and supervised the project. A.X. performed the crystal synthesis, X-ray imaging, most of the data analysis, and paper writing. C.H. carried out the XRD measurement. F.M. contributed to the X-ray imaging. M.E.W., M.M., and W.D. contributed to the temperature-dependent X-ray luminescence, thermoluminescence, and gamma-ray characterizations. A. and A.T.S.W. performed the XPS measurement. S.V.S. carried out the alpha particle pulse-height measurement. P.Q.V. and H.J.K. contributed to the pulse-shape discrimination, thermal neutron measurements, and the related data analysis. Christophe D. and P.C. contributed to the data analysis. All authors contributed to the discussion and the writing of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, A., Hettiarachchi, C., Maddalena, F. et al. Lithium-doped two-dimensional perovskite scintillator for wide-range radiation detection. Commun Mater 1, 37 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-020-0038-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-020-0038-x

This article is cited by

-

Development and challenges in perovskite scintillators for high-resolution imaging and timing applications

Communications Materials (2023)

-

Two-Dimensional Metal Halides for X-Ray Detection Applications

Nano-Micro Letters (2023)

-

X-Ray imager of 26-µm resolution achieved by perovskite assembly

Nano Research (2022)

-

2D perovskite-based high spatial resolution X-ray detectors

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Hybrid halide perovskite neutron detectors

Scientific Reports (2021)