Abstract

Commercialization of lead halide perovskite-based devices is hindered by their instability towards environmental conditions. In particular, water promotes fast decomposition, leading to a drastic decrease in device performance. Integrating water-splitting active species within ancillary layers to the perovskite absorber might be a solution to this, as they could convert incoming water into oxygen and hydrogen, preserving device performance. Here, we suggest that a CuSCN nanoplatelete/p-type semiconducting polymer composite, combining hole extraction and transport properties with water oxidation activity, transforms incoming water molecules and triggers the in situ p-doping of the conjugated polymer, improving transport of photocharges. Insertion of the nanocomposite into a lead perovskite solar cell with a direct photovoltaic architecture causes stable device performance for 28 days in high-moisture conditions. Our findings demonstrate that the engineering of a hole extraction layer with possible water-splitting additives could be a viable strategy to reduce the impact of moisture in perovskite devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stability to environmental humidity is the main bottleneck delaying perovskite solar cell (PSC) commercialization1,2. It is widely accepted that most of the degradation pathways in photoactive perovskite layers come from water permeated within photovoltaic devices, that irreversibly depresses their figures of merit. Water quickly promotes the transformation of the perovskite salts into their precursors3 and the process is even faster under light illumination4. Silicon solar cells do not suffer from this problem and thus they are steps ahead in the photovoltaic market.

In order to avoid moisture permeation, PSC can be robustly engineered with the application of hydrophobic ancillary layers or with complex device encapsulation5. In this way, examples of PSC working for several thousands hours have been reported in the literature6,7,8. Nevertheless, despite all the big efforts coming from the scientific community to avoid penetration of water up to the photoactive halide perovskite layers, this major issue still remains extremely relevant for determining device lifetimes and innovative disrupting approaches are required to proceed further towards PSC commercialization.

A possible solution could derive from the incorporation of materials having water-splitting (WS) activity within one of the layers adjacent to the perovskite film in a solar cell multilayer architecture. For example, in a direct architecture PSC, the hole-transporting layer could be engineered to act as charge extractor/transporter layer and as a functional scavenger for moisture at the same time, hindering water penetration not only through instrinsic hydrophobicity (a very popular strategy to stabilize PSC nowadays) but by transforming the water molecules into other harmless or even beneficial species.

Photocatalytic WS is the process at the base of artificial photosynthesis9,10, allowing the chemical dissociation of water into molecular hydrogen and oxygen. It requires energy (light or bias), a catalyst and water. The mechanism is straightforward:11 a theoretical energy difference of at least 1.23 eV is required in order to promote water oxidation. Different materials, mainly inorganic semiconductors12, are known having WS properties due to their favorable energy alignement with respect to the oxygen/hydrogen evolution potential.

Within this scenario, the essential requirement for realizing a WS-active hole-transporting material (HTM) would be to identify species that combine hole transport with water oxidation activity (2 H2O → O2 + 4H+ + 4e-). A major candidate for this role can be found in copper thiocyanate (CuSCN), which has been shown to act as an excellent HTM13, with high hole-mobility, good energy level matching with perovskites, thermal stability, hydrophobic properties and low production costs. The use of CuSCN as HTM in conjunction with a reduced graphene oxide interfacial thin layer with the top metal electrode, provided a remarkable stabilized power-conversion-efficiency (PCE)14. At the same time, this material has been used to efficiently assist oxygen evolution in CuSCN/BiVO4 photoelectrodes15. On the other hand, CuSCN is not used alone for photocatalytic WS, given the scarce absorption properties in the visible range. Within a PSC anyway, the perovskite layer itself and/or the CuSCN, with its optimal Fermi level, would be responsible for light harvesting and biasing of the electrochemical reaction.

CuSCN large-scale adoption is still limited by the sub-optimal processing employed for the deposition on top of the perovskite layer, which consists in an un-controlled drop-casting from diethyl sulfide (DES) concentrated solutions. Such a procedure is highly user-dependent and, therefore, suffers from a potentially scarce reproducibility. In addition, it does not ensure a perfect solvent orthogonality with the underlying perovskite, which is exposed to partial dissolution by DES and consequent damage, ultimately affecting the device performance14,16. In this regard, the production of CuSCN in the form of solution-processed nanostructures has not yet been reported to the best of our knowledge, but it might allow the use of more suitable solvents and reproducible deposition techniques.

Here, we propose the use of ligand-free CuSCN nanoplatelets (CuSCN-NP) produced through continuous flow hydrothermal synthesis (CFHS). This water-based synthetic route follows the principles of green chemistry and allows to obtain a wide variety of nanomaterials with applications ranging from biomedicine to printed electronics and photocatalysis17. The platelet-like geometry of these inorganic nanomaterials is ideal for use in multilayers, thin films-based devices.

On the other hand, this choice also forces to identify a dispersion phase in which incorporate CuSCN-NP for solution processing, that can work at the same time as an hole transporter, in order to facilitate the overall charge extraction process from the perovskite layer. A polymeric hole-transporter such as poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT), a well-established, inexpensive, organic p-type polymer characterized by an outstanding film forming ability and a good matching with the copper(I)-based inorganic semiconductor valence band18, appears to be the most suitable choice, although undoped P3HT is not generally applied as HTM when high PCEs are targeted19,20,21. By dispersing CuSCN-NP in P3HT, a nanocomposite HTM is produced, that can be defined as CuSCN@P3HT.

In this work, we demonstrate that CuSCN@P3HT could work as a WS-active combination for preventing the moisture-mediated degradation of a PSC and for the concomitant in situ p-doping of the P3HT HTM phase, that further affects favorably the figures of merit of the direct architecture PSC in which it is integrated. This virtuous physico-chemical process ensures the maintenance of a good PCE of >9% in PSC stored for one month in a water-saturated atmosphere, making these insights a very promising platform for stimulating future investigations on smart approaches to preserve operation in optoelectronic devices22 suffering from scarce stability to environmental moisture.

Results and discussion

Materials synthesis and characterization

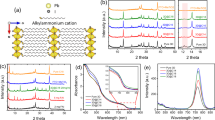

The synthesis of surfactant-free CuSCN-NP was performed by CFHS, as reported in detail in the “Methods” section and schematized in Supplementary Fig. 1. The CuSCN-NP can be visualized in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figure. From transmission electron microscopy (TEM) picture (Fig. 1a) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) pictures (Supplementary Fig. 2a), they appear to have a platelet-like shape. Analysis through dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Fig. 1b) show that particles have a narrow size distribution with an average value nor exceeding 600 ± 160 nm. TEM shows also the presence of a small fraction of particles that are significantly thinner, as shown in the inset of Fig. 1b and in Supplementary Fig. 2b–e. These lamellae have a lateral size in the 50–100 nm range and are significantly more electron-transparent than most of other particles, hinting of a thickness of only few nanometeres.

a Representative TEM image of CuSCN-NP from water dispersion employing keratin as surfactant and b size distribution measured by DLS, with TEM image at high magnification in the inset showing the presence ofsignificantly thin platelets within the sample. c XPS characterization of CuSCN-NP: top left, Cu 2p3/2 XPS peak with fitted Cu(I)SCN component (blue); top center, Cu LMM Auger spectrum; top right, N 1s XPS spectrum fitted with SCN (blue) and thiourea (green) component; bottom left, C 1s XPS region with aliphatic (blue), SCN (green), thiourea (violet), carboxylate (ochre) components; bottom center, S 2p region with the main doublet assigned to SCN and thiourea (2p3/2 blue, 2p1/2 green), and the satellite doublet corresponding to oxidized sulfur (violet and ochre); bottom right, XPS valence band spectrum with red dashed lines indicating the valence band onset.

The optical band gap of the CuSCN-NP is slightly higher than the reported one for bulk CuSCN (3.6 eV)16, as evidenced by the corresponding Tauc Plot (Supplementary Fig. 3a), from which an optical direct band gap of 4.1 eV is estimated. The higher value for the band gap can be attributed to the particular aspect ratio of these nanomaterials, with an electronic behavior resembling that of quantum wells23. The platelet structure of these nanomaterials is further corroborated by examining the line shape of the Tauc Plot at low energy: this analysis is a well-known methodology for the determination of the optical properties of semiconducting nanoparticles24, in particular for revealing the presence of defects, i.e., a continuum of tail states within the particles band gap25. These states (called Urbach states) can be reasonably considered as a measure of the disorder in nanocrystals. An exponential decay of the optical absorption is observed beneath the gap in our CuSCN-NP and an Urbach energy (Eu) of about 0.19 eV is estimated by using the relationship26:

where α is the absorption coefficient (the corresponding Urbach fit is reported in Supplementary Fig. 3a for the sake of clarity)25. This value is in agreement with previous literature data on nanostructured CuSCN obtained by electrodeposition in the form of nanowires and two-dimensional platelets27.

A more detailed elemental and structural characterization of the material, through X-rays diffraction (XRD) analysis and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), shown respectively in Supplementary Fig. 3b–c, clearly demonstrate that the investigated sample is crystalline and mainly composed of the R-3m trigonal copper thiocyanate phase (β-CuSCN). The presence of preferential orientation of the crystallites suggests that particles diplay a tendency to stack along the [00l] direction (as seen from XRD, Supplementary Fig. 3b)14. This is compatible with the formation of platelets undergoing a preferential growth along the [h k 0] directions. However, the data also indicate the existence of other spurious copper-based phases, evident in the XRD pattern, maybe traces of CuS (covellite) and minor forms could be present, probably related to hydrated CuSx phases, and confirmed by the unproper stoichiometry of Cu:S:C:N (Supplementary Fig. 3c). In order to deeper investigate the source of this contamination, the structural characterization is completed through X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements, shown in Fig. 1c. The Cu 2p3/2 region shows a single component at 932.5 eV, in agreement with values reported for CuSCN (there could be a minor component corresponding to Cu oxides)28. The absence of satellite peaks in the binding energy (BE) region 935–940 eV suggests that Cu (II) species, in particular Cu(II) oxides and hydroxides, are not present in significative amounts. The attribution of the Cu(I) oxidation state of the metal is confirmed by the Cu LMM Auger spectrum, characterized by a peak at kinetic energy at 915.3 eV, and the modified Auger parameter (Cu 2p3/2 BE + Cu LMM KE) of 1847.7 eV29. The contamination is ascribed to thiocyanate ligand and residual thiourea from the synthesis that could not be removed even after the thorough washings, as can be identified by N 1s, C 1s, and S 2p peaks at characteristic BE values27,30. The N 1s region is characterized by the presence of two peaks at BE 398.7 eV and 400.3 eV, which are assigned to thiocyanate and thiourea respectively. The carbon 1s region exhibits multiple peaks that correspond to the thiocyanate ligand (BE 286.3 eV), alifatic carbon contaminants (BE 285 eV), thiourea (BE 288.2 eV) and carboxylate (BE 289.9 eV) functional groups. Sulfur 2p region is dominated by a doublet corresponding to both SCN and thiourea (S 2p3/2 BE = 163.5 eV), while a small contribution from oxidized sulfur is present with BE ≈ 169.4 eV. In conclusion, no real XPS evidences of covellite-based signals from S 2p are found since no peaks at 161 eV are detected, as previously determined by some of us as a typical signature of this phase31. The presence of thiourea detected through XPS suggest a second partial interpration of the increased optical band gap of the CuSCN-NP compared to bulk CuSCN as extrapolated from the Tauc plot in Fig. 1d: a previous literature report on a similar case32 describes how the band gap of a ZnS thin films resulted to be singificantly affected by the presence of residual thiourea precursor, when a chemical bath deposition process was employed to fabricate it. Attempts to perform local structural analysis through selected area electron diffraction (SAED) during TEM imaging were unsuccessful (at both high, 200 kV, and low, 80 kV, acceleration voltages), due to instability of the particles under the electron beam during data acquisition33, a behavior that is compatible with the presence of beam-sensitive hydrated CuSx phases.

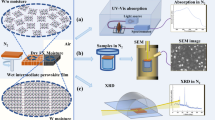

A CuSCN@P3HT composite is prepared by blending the ligand-free CuSCN-NP in solid powder form in a P3HT solution, as described in the “Methods” section. The model solar cells for CuSCN@P3HT HTM integration and test of WS-activity is based on a standard architecture PSC with ITO/SnO2/perovskite/HTM/Au configuration, where tin oxide is the electron transporting layer (ETL). However, before solar cell testing, a clear understading of the WS process is mandatory.

For this reason, the WS activity of CuSCN@P3HT—in comparison with that of bare P3HT—is investigated by conducting linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) measurements in a 3-electrode configuration, employing HTM/Au/ITO partial devices as the working electrode, a Pt wire counter electrode and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Experimental details on the preparation of the system and on the electrochemical measurements are given in the “Methods” section. The electrochemical characterization covered both the anodic and cathodic sides of the WS process. This allowed to retrieve useful insights on the behavior of the HTM toward both the reduction and oxidation reactions necessary for the moisture elimation effect to occur in within the solar cell. The LSV at the anodic limit (Fig. 2a) highlights a remarkable difference between the composite and neat P3HT film. The polarization curve shown is performed alternating light and dark regime each 0.05 V. Irrespective of the measurement conditions (i.e., under 1 Sun illumination or in dark), the CuSCN@P3HT HTM current density is: (i) cathodically shifted of around 0.2 V with respect to the neat P3HT HTM; (ii) two orders of magnitude higher @1.23 V vs. RHE. No photo-enhancement effect occurs. Nevertheless, these results corroborates the idea that the composite HTM facilitates the reactions steps, which lead the H2O molecules to give gaseous O2.

a Linear sweep voltammetries in the anodic regime of CuSCN@P3HT-based (red line) and P3HT (black line) working electrodes. b EPR spectra in dark at low temperature of pristine P3HT, CuSCN-NP, and CuSCN@P3HT. The amount of P3HT across the two different samples is the same. For the sake of clarity, the EPR signal for CuSCN@P3HT is reduced by a factor of 5. c Energy levels diagram of CuSCN@P3HT (right), illustrating qualitatively the hole transfer process obtained after blending CuSCN-NP with P3HT (left). The P3HT work function value was taken from previous reports of some of us21,47. The dashed areas qualitatively represent filled states in CuSCN-NP (green) and in CuSCN@P3HT (black).

On the cathodic side, the electrochemical behavior of the two materials is even more diversified. First, a contribution coming from photogenerated charges arises, as it can be seen from the LSV in light-dark alternating regime (Supplementary Fig. 13a, b). Thus, it is reasonable to infer that the residual photons, which are not absorbed by the photoactive layer (which in a conservative approach are estimated to be in the order of 5% of the full light intensity, based on the EQE spectra reported in Supplementary Fig. 11) may contribute to generate a photovoltage, which may further reduce the required bias. Additionally, the two materials react differently to the presence of molecular oxygen dissolved in the electrolyte. In de-aerated conditions (i.e., purging with N2 the electrochemical solution), the neat and composite P3HT film show almost the same behavior both in light and dark conditions up to −0.1 V vs. RHE. In the potential region below −0.1 V vs. RHE, a HER reaction onset can be identified when CuSCN is present. This highlights how this material plays a role also in catalysing the cathodic half reaction of the water-splitting process. Furthermore, when working in aerated conditions the composite material shows an increase in current density both in light and dark conditions, while the neat film current increases only upon illumination. This can be addressed to surface polarization effects, which facilitate the charge transfer process between adsorbed O2, dissolved in the solution, and the P3HT film34. For the composite film, the increase is proportional to the magnitude of the current when no light is shone to the device. Thus, the different behavior between the two materials is tied to the presence of CuSCN which, again, facilitates the binding and charge transfer between the film and the reactants.

The overall process (2H2O(l) ⇌ 4H+ + O2(g) + 4e−) is therefore energetically favored when the composite HTM is used. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first experimental evidence of a WS process involving P3HT and CuSCN.

The intermediate steps that lead to the formation of molecular oxygen are those for which most of the energy must be spent. Neverthless, the suggested effect may still occur as soon as the dissociation process of water molecules into its constitutive elements reaches the second reaction step (HO* ⇌ H+ + O* + e−). An oxygen atom adsorbed to an electrochemical active site (O*) can then participate in the p-doping process of P3HT.

While it is certainly true that the working conditions are dramatically different with respect to the ones occurring during the electrochemical measurements, it is reasonable to infer that the underlying mechanisms just described can hold true also in high RH% environments. The decrease in magnitude of the effects in real working conditions can be reasonably assumed to be roughly proportional to the water content in atmosphere, i.e., 6 o.o.m lower. Nevertheless, it may still be a valid explanation for the effect occurring on the full solar cell.

In order to get deeper information on the charge transfer process happening within the composite material, we performed an electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analysis of the samples in dark conditions.

This technique is very sensitive to the presence of localized unpaired electrons within materials, therefore allowing us to better highlight the electrical role of the CuSCN-NP dispersed in the P3HT phase. In the present case, it reveals a considerable increase of the characteristic pristine P3HT signal for long-lived polarons, i.e., trapped positive charges, that naturally occur in p-type organic semiconductor material due to partial oxidation (Fig. 2b)35. Such a result indicates that an overlap of the electronic bands of the two materials occurs, which may allow charge transfer between CuSCN and P3HT. This result is in agreement with an energy levels analysis conducted through Kelvin Probe (KP) microscopy and XPS. From KP, a value for the Fermi level of CuSCN-NP at −4 eV is obtained (Supplementary Fig. 4a), whereas the XPS valence band spectrum, obtained employing the Mg k-alpha radiation, shows several bands, which are in agreement with experimental and calculated spectra of CuSCN (Fig. 1c right bottom panel)28. The onset of the valence band photoemission, corresponding to the valence band maximum, is found at 1.3 eV below the Fermi level, thus allowing us to design an energy level diagram, as reported in Fig. 2c. The intimate contact between P3HT and CuSCN-NP that favors charge transfer (schematically sketched in Fig. 2c) is further proved by examining spin relaxation processes through EPR. Supplementary Fig. 4b reports the decay of transverse magnetization over time for P3HT charged species. It is evident that the spin relaxation time for P3HT is significantly shortened when the polymer interacts with proximal Cu(I) centers, i.e., CuSCN acts as a “magnetic” quencher for P3HT charged states, in analogy with an optical quencher in a time-resolved photoluminescence experiment. In addition, the spatial range of the magnetic interactions leading to increased spin relaxation implies a close contact between the two species involved (less than a few nanometers).

To summarize, the spectroscopic and structural evidences suggest that the organic/inorganic nanocomposite CuSCN@P3HT features intriguing properties that perspect application in PSC. These are, namely, the platelet-like morphology of the CuSCN-NP, that is coherent with a vertical architecture of the PSC in which each layer is processed through spin coating, the ability of P3HT to efficiently disperse the inorganic fillers, the favorable overlap of energetic bands, which may favor a charge transfer process, and, more relevantly, the experimental evidence that proves the good WS activity of the nanocomposite compared to the pristine polymeric HTM. This allows the fabrication of the first rationally design PSC, to the best of our knowledge, that incorporates a WS active HTM.

Perovskite solar cells fabrication, characterization, and stability test

PSC containing the binary blend HTM were fabricated as described thoroughly in the Methods Section. P3HT and three CuSCN@P3HT HTM with two different concentrations of CuSCN-NP in the polymer matrix (5 wt% and 10 wt%, respectively) were employed. A preliminary screening of the HTM moisture compatibility was carried out before preparing PSC, through water contact angle measurements. Wettability characterization performed on the different P3HT-based HTM do not show any significant variation in the organic-inorganic composites compared to pristine P3HT (Supplementary Fig. 5 reports the case of pure P3HT and of 10% CuSCN@P3HT, while the case of the intermediate CuSCN concentration is not shown since identical, with an approximate contact angle value of 100°) and thus we can infer that the well-known hydrophobic character of this polymeric material remains unchanged upon blending. Furthermore, inspection of the spin-casted layers underneath water drops reveals smooth films, which point out at a good morphological homogeinity of the CuSCN@P3HT composites. These evidences prospect a favorable use of the blends as good water-resistant HTM for direct architecture PSC.

The procedure previously described for preparing mixed-cation perovskites36 is applied also here for the construction of the active layer. A standard PSC architecture based on ITO/SnO2/(FAPbI3)0.87(CsPbBr3)0.13/HTM/Au is built for each device, containing one of the different HTM whose performance has to be compared. Devices are characterized morphologically through SEM. The good dispersion of the CuSCN-NP in the polymer film makes difficult to discern the presence of the inorganic nanofillers from top-view images of the perovskite/HTM interface, even if the comparison with the case of pure P3HT highlights the existence of entities having a different contrast with sizes of hundreds nm in the composite HTM (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). However, the platelets are clearly visibile in the cross-sectional image shown in Supplementary Fig. 5d, in which horizontal wrinkled structures (indicated with blue arrows) of several hundreds of nm length are detectable within the HTM. To make this layer more visible, the polishing step was on purpose avoided in the samples for cross-sections, thus allowing the better observation of the intrinsic HTM morphology, which appear more adhesive in the composite compared to P3HT. However, Supplementary Fig. 5e, f show the polished cross-sectional images, from which the HTM thickness can be estimated to be of about 100 nm. Furthermore, AFM imaging of the dispersed CuSCN nanoparticles are provided in Supplementary Fig. 12 in which lamellae-like structures are found with an average lateral dimension of about 600 nm and a maximum thickness of 200 nm, thus corroborating the idea that this material can be incorporated into the polymer phase during processing.

In order to verify the impact of the WS process occurring within the composite HTM, the as-prepared PSC are freshly tested and then stored both in a glovebox (“dry” environment) and in a home-made container where a water-saturated atmosphere (RH > 80%) is generated (“humid” environment). The devices are maintaned in the two different conditions for 28 days and photovoltaic data are acquired at different time points during the endurance test (see Supplementary Fig. 7 for the overall data).

In Tables 1 and 2 the summary of the figures of merit for all devices is reported at day 0 and day 28, both in dry and in humid. An “hysteresis factor” is calculated as the ratio between average PCE values obtained from forward (f) and reverse (r) current density–voltage (J–V) scans: the higher is the value, the higher is the hysteresis.

Analysis of the data reported in Tables 1 and 2 shows that the reference PSC based on the pristine P3HT HTM undergo a degradation process after almost one month storage in humid conditions that is not detected in devices kept in a dry environment (32.5% loss in average PCE against 0.1% loss), whereas the performance of the PSC containing the additional 5 wt% CuSCN-NP contribution in a water-saturated atmosphere changes very moderately (−11.6%). In this last case, the hysteris factor is even slightly improved (from 1.96 at d 0 to 1.57 at d 28). Generally humidity affects the perovskite layer integrity (and more specifically the corresponding device short-circuit current density, Jsc), therefore a wettability determination would be mandatory to exclude an additional hydrophobic effect of the CuSCN additives that protects the photoactive layer in an extremely humid environment. As discussed previously, the presence of the CuSCN-NP in P3HT up to 10 wt% does not change the water contact angle with respect to the already very hydrophobic P3HT (see Supplementary Fig. 5). Therefore, assuming that moisture can penetrate in all devices, other effects must justify the stable performance of the 5 wt% CuSCN@P3HT containing devices stored in humid conditions, especially of the lowest hysteresis and the highest open circuit voltage (Voc) compared to all other cases examined in the same conditions.

In Fig. 3 PCE and Voc statistical data for a large number of as-prepared (d 0) and aged (d 28) devices based on P3HT and 5% CuSCN@P3HT HTM are plotted, in both forward and reverse scans. As mentioned above, the average PCE for the P3HT-based PSC is notably decreased in humid atmosphere, whereas it remains almost unvaried for the 5% CuSCN@P3HT-based ones. Interestingly, the only figure of merit that has a significant variation in 5% CuSCN@P3HT after ageing in humid is the short-circuit current (Jsc), dropping from >19 mA cm−2 at d 0 to about 17 mA cm−2 at d 28. Also the value at d 0 is higher for CuSCN-containing samples with respect to P3HT control sample (18.49 mA cm−2, 19.12 mA cm−2, and 19.41 mA cm−2 for P3HT, 5% CuSCN@P3HT and 10% CuSCN@P3HT samples, respectively). The incident-photon-to-electron conversion efficiency (IPCE) spectra provide hints to understand the better Jsc in the CuSCN-containing devices (Supplementary Fig. 11): in the high-energy region the IPCE signal is indeed higher for these last ones compared to P3HT-only devices at d 0. These data can be trivially explained with the fact that the inclusion of CuSCN-NP in the composite HTM boost light absorption of about 10% in the ultraviolet (UV)/blue region, with the consequent production of photocharges that contribute to the overall Jsc extracted from the PSC. It is generally accepted that low IPCE intensities at high energies are due to sub-optimal transport/photocharge injection at the perovskite/HTM interface37, therefore we can argue that CuSCN has a good impact on the hole mobility in such conditions. However, at d 28 similar IPCE are found for both samples, suggesting that any beneficial contribution of CuSCN addition to the Jsc is to be neglected after ageing. Furthermore, we speculate on the IPCE enhancement of CuSCN@P3HT origin attributing to the favorable energy level alignment for efficient hole transfer: the CuSCN nanoplatelets embedded in P3HT construct a favorable energy level alignment by making the energy level of the hole transport layer lower. We expect that the hole transport and extraction is improved in the device with CuSCN@P3HT-based HTM, which induces enhancement of IPCE at the wavelength of 300–500 nm, as previously occurred in solar cells when CuSCN layer is aplied38.

Statistical data on PCE and VOC variations during 28 days in a water-saturated atmosphere (humid, pale blue) and in a dry atmosphere (dry, red) for PSC containing a, c the reference P3HT and b, d the 5% CuSCN@P3HT HTM. Best pixel J–V curves for the P3HT-based device e and for 5% CuSCN@P3HT-based device f as prepared (0 d) and after the 28 days of endurance test in high-humidity conditions (28 d). The complete dataset of photovoltaic parameters is reported in Supplementary Fig. 7.

A best pixel with 9.6% PCE is found for the 5% CuSCN@P3HT containing PSC at d 28, whereas a 7.85% PCE results for the P3HT-based reference (reverse scans in Fig. 3a, b). In addition, the dispersion of PCE data is significantly high for P3HT-based devices at d 28 in humid conditions, whereas it is much smaller for the CuSCN-contanining PSC. This aspect points out at the fact that moisture must have a relevant role in determining the fate of the solar cell. However, knowning that water tends to degrade the perovskite layer affecting Jsc values (see Supplementary Fig. 8a, b) and, consequently PCE, the analysis of the other figures of merit, Voc (Fig. 3c, d) and fill factor (FF, Supplementary Fig. 8c, d), emerges as an helpful tool to understand more in detail the nature of the degradation mechanism.

Voc of solar cells is analyzed in Fig. 3c, d: Voc values for P3HT-only devices are strongly affected by the high humidity, while they are slightly changed or even improved when CuSCN is present. The opposite happens in dry conditions: Voc (and also Jsc) is improved in the P3HT control solar cell, while a serious degradation occurs with CuSCN-NP. Both high Voc and Jsc values are normally related to optimal interfaces between adjacent layers: at d 0, the energy alignment of the perovskite layer and the composite HTM is not ideal, being the work function of the latter very similar to the conduction band of the former (4 eV vs. 3.39 eV). This may depress photocurrent and photovoltage, due to recombination of excitons. We can therefore infer that a dry environment is the sub-optimal working condition for our CuSCN@P3HT composite HTM in a standard architecture PSC, while the material requires a humid atmosphere to express its potential in stabilizing solar cells performance.

In this context, a spectroscopical characterization such as time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL), that probes the ageing effect of the two opposite humidity conditions directly on the photoactive perovskite layer, can be helpful in better understand the degradation processes happening in the devices. We examined and compared the decay of the photoluminescence (PL) emission at 780 nm, to extract the lifetime of the carriers in the perovskite layers (see Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). After the photoexcitation (600 nm) of the perovskite films in solar cell architectures, many processes may determine the overall lifetime of the carriers, among which most significant are carrier trapping, carrier extraction, and radiative recombination. It is worth to note that both carrier trapping and extraction in and from the perovskite layer are expected to decrease the carrier lifetime, while only the carrier extraction contributes to the photovoltaic efficiency. To get a qualitative insight into the degradation process, we compared the average lifetime of the carriers with the recorded average PCE of the solar cells (Fig. 4a, b). The P3HT-only device aged in “dry” conditions displays a slightly shorter average lifetime \(\left( { < \tau > _{{\mathrm{P3HT}}} = 10 \pm 1\,{\mathrm{ns}}} \right)\) despite showing the higher photovoltaic performance. On the other hand, the 5% CuSCN@P3HT device reports a longer lifetime \(\left( { < \tau > _{{\mathrm{CuSCN}}\,5\% } = 11 \pm 1\,{\mathrm{ns}}} \right)\) while reporting lower PCE. Therefore, this qualitative anticorrelation of lifetimes and PCE during the dry ageing suggest that different degrees of degradation in the charge extraction layer (HTM) are partly responsible for the losses in the photovoltaic efficiency. This translate in poorer carrier extraction and thus longer PL lifetimes. On the other hand, the qualitative comparison shows the opposite trend for ageing in “humid” conditions: over the series, shorter average lifetimes of carriers in the perovskite films are associated with poorer photovoltaic performances. Therefore, the comparison suggests that the humidity-driven degradation of the perovskite layer (i.e., increased carrier trapping) is responsible for the degradation of photovoltaic performances. Notably, these results suggest that in “humid” conditions the presence of 5% CuSCN-NP additives preserves the photovoltaic performances, i.e., preventing the perovskite degradation as quantitively demonstrated by fitting the PL decays.

We measured excitation power dependent TRPL spectra (Supplementary Fig. 10) and analyzed the kinetics of the PL decay according to the differential rate law:

Given the free carrier nature of hybrid lead iodide perovskites, the monomolecular recombination rate k1 is ascribed to carrier trapping processes, while the bimolecular recombination rate constant is ascribed to the radiative recombination. However, since we studied the carrier dynamics in solar cell architectures, k1 also contains information on the carrier extraction and therefore can be expressed as \(k_1 = k_T + c_{{\mathrm{ext}}}\). As reported in Table S1 in the SI, k1 values in the humid conditions are lower for the 5% CuSCN@P3HT cell and, considering PCE data, we can safely determine that the presence of small quantities of the inorganic semiconductor additive in the HTM help in protecting the perovskite layer.

In order to better understand the origin of this peculiar behavior of the 5% CuSCN@P3HT composite HTM observed in humid conditions and in which extent it can be related to the WS process hyphotetized, we tracked the WF of the different HTM in the two opposite environmental conditions (humid and dry) using KP. Indeed, a better hole-extraction is usually linked to a favorable energy alignment between the HTM and the top electrode (Au in this case). A pn junction is generated by spin coating the different p-type HTM semiconductors on top of FTO substrates, that in this case act as the n-type semiconductor. In such a way, a built-in potential is established within the devices, that simulates the cell working mechanism during Voc application, i.e., a flow of charges towards FTO (the negative ones) and through the HTM (the positive ones). The estimation of the WF can be reasonably associated with the actual energy of the Fermi level at the FTO/HTM interface and its eventual shifting is strongly related to the presence of active defects in the band gap of the semiconductors that increase energy losses (i.e., decrease Voc). In Fig. 5a the average measured WF of the different HTM is reported. In order to ease the correct understanding of KP data, the HTM WF values are reported as a difference with respect to the gold WF. Owing to the nature of the tip used for the measurement (see SI for details) this choice is particularly helpful, because Au represents also the anode metal at which holes are collected in the PSC. Therefore, the more positive is the energy difference, the higher is the WF of the HTM and the better the HTM should work in a PSC as transport layer in a given environmental condition. P3HT and 5% CuSCN@P3HT clearly show the most suited energetic conditions with an actual WF of about −5.1 eV (almost no difference with respect to Au, that we assign to −5.1 eV, as from literature data39). On the contrary the WF of 10% CuSCN@P3HT is located at −5 eV. In dry conditions the system behaves completely different, with P3HT having a WF of about −4.8 eV, and thus confirming the undoped nature of the pristine semiconducting polymer18. Five percent CuSCN@P3HT shows large data dispersion, a result that is in accordance with EPR results in dark (Fig. 2b) that, by confirming the charge transfer process between the two materials in the binary composite, suggests how the WF could change locally within the HTM depending on the presence or not of CuSCN-NP in a given position.

a Chart summarizing Kelvin probe analysis: “humid” and “dry” behavior are compared in different colors. The zero value in the y-axis represent the WF of Au. b Proposed mechanisms for the two processes happening within the WS-integrating PSC. The “main mechanism” (violet) is the regular working process of the PSC. The “parasitic mechanism” is the hyphotetical WS-process occurring at the perovskite/CuSCN@P3HT interface. This last one takes place because, during the endurance test in a water-saturated atmosphere, moisture, diffusing from the top of the device, is locally oxidized by the CuSCN-NP center contained in the composite HTM, forming in situ molecular oxygen, that p-dopes the semiconducting P3HT matrix. The required energy difference for WS is guaranteed by the valence band position of p-doped P3HT and Fermi level of CuSCN (indicated with the 4.0 value in the scheme) acting as, respectively, anode and cathode sites for the WS reaction, whereas the flow of the charges is supported by the built-in potential (in dark during the storage) or by the bias (during solar cell electrical characterization).

Thus, from the comparison, we can state that humid conditions favor an increase in the WF of the different HTM containing CuSCN (pail blue pattern), i.e., we can attest that a p-doping process occurs. Considering the WS process, we can assume that the doping agent for P3HT is molecular oxygen derived from the water oxidation reaction. Based on this, it derives that the WS process occurs simultaneously to PSC operation, as described in Fig. 5b. To the main PSC working mechanism (i.e., the flow of charges into the external circuit), a parasitic mechanism (i.e., the WS itself) is added to the overall PSC operation: when water diffuses within the top layers, some photoexcited holes immediately convert it to molecular oxygen, that, due to the very short distance between CuSCN-NP centers and P3HT, p-dopes the semiconducting polymer (i.e., the HTM Fermi level is lowered towards optimal transport conditions). On the other hand, a marginal fraction of photoexcited electrons in the conduction band of the perovskite close to the HTM can diffuse to the HTM itself due to the presence of protons, reducing them to obtain molecular hydrogen, as shown in Fig. 5b. The suitable WF of CuSCN (4 eV as determined by KP, see Fig. S4a) and the electrochemical measurementes addressing the cathodic reaction support this evidence. In this way, water molecules can be in situ degraded, while perovskite layer integrity and, consequently, PSC operation can be preserved from undesired chemical degradation.

We speculate that, in the present case, water molecules diffusing from the top of the unsealed PSC into the composite HTM during the endurance test carried out in a water-saturated atmosphere, react with the CuSCN-NP water oxidation centers when the device is biased during J–V scans, by forming molecular oxygen. It is well-known that P3HT can be p-doped in presence of oxygen and light40,41,42. Therefore, in the binary HTM system, in which an unfavorable starting situation, deriving from a misalignment of the energy levels, depresses PCE, the rise in oxygen content following water and light exposure, allows the p-doping of the polymeric hole conductor and thus pins down the Fermi level towards an optimal value, by in situ reducing energy losses. The opposite happens when moisture is not present: in this case the polymer doping is not effective and only a charge transfer process takes place between the constituents of the HTM, thus locally altering the Fermi level of the system in a chameleonic way, that depends on the specific point in the HTM where CuSCN-NP are either present or not.

The implementation of a WS-integrated PSC in high-humidity environments has an impact on the figures of merit: (i) a robust increase of the average Voc (see Fig. 3d); (ii) a decrease of the electrical hysteresis (see Table 1) due to the lower amount of water reaching the perovskite, being the former transformed into oxygen (comparable Jsc, see Table 1), and (iii) a slightly higher fill factor (FF) due to a reduced series resistance allowed by a better quality perovskite/P3HT-based HTM interface (see Supplementary Fig. 6).

In this work, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, the water oxidation capability of an inorganic semiconductor is exploited as a tool to preserve the functionality of a lead halide perovskite-based solar device maintained under significant stress-conditions of high relative humidity. This concept is per se relevant for opening up new perspectives in the stabilization of last generation optoelectronic devices based on water-sensitive species.

The active role of the wide-band gap CuSCN-NP in the composite HTM that we described here is not only that of electron-blocking species (which is anyway relevant, as seen from the high Voc of the solar cells after one month of moisture exposition), but could also be that of selective oxidants for the moisture diffusing within the HTM during PSC ageing. In this way, the oxygen production within the HTM could trigger the favorable in situ p-doping of P3HT.

The here presented results, specific on PSC, interestingly pioneer a research field in which also other inorganic nanomaterials besides CuSCN-NP could be employed as mediators for promoting p-doping of semiconducting polymers-based optoelectronic devices operating in humid environments, after designing and applying a proper tuning of the adjacent layers and of the overall energy levels landscape.

Methods

Materials

All materials and solvents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, unless otherwise specified, and used as received. PbI2, PbBr2 and CsBr were purchased from Alfa Aesar. Formamidinium iodide (FAI) was obtained from Dyesol. P3HT was purchased from Merck (Mw = 94.100 g mol−1, PD = 1.9, RR = 95.5%).

Synthesis of CuSCN-NP

The material was produced through CFHS in a lab-scale reactor. The reactor was made from off-the-shelf Swagelok™ parts and equipped with two patented confined jet mixers43. The mixers were fed by three Primeroyal K diaphragm pumps (Milton Roy, Pont-Saint-Pierre, France, pressurized to 24.1 MPa; see Supplementary Fig. 1 for a sketch of the reactor). Pump 1 was employed for the supercritical water line at 80 ml min−1, where water was heated in line at 450 °C using a custom-made 7 kW heater. Pump 2 was used to feed a 0.5 M thiourea solution to the first mixer at 40 ml min−1, to allow its thermal decomposition leading to the production in situ of SCN- at 380 °C44. Pump 3 was then used to pump a 0.1 M Cu(NO3)2·3H2O solution to the second mixer at 100 ml min−1, allowing the precipitation of CuSCN from the mixing with the SCN- solution at 260 °C. The residence time between the first and the second mixer was 2.28 s. The product was collected as slurry in a simple flask. Once the solid product settled, the clear solution above was carefully removed. The product was isolated though centrifugation (10 min at 10,000 rpm), then it was washed by adding fresh water and isolated again though centrifugation (10 min at 10,000 rpm) for four times. The clean solid was freeze-dried, grinded, and stored in a common Falcon tube.

XRD analysis

XRD measurements for crystal phase identification were carried out at room temperature by a Bruker D8 Advance Diffractometer equipped with a Göbel mirror, using the Cu-Kα radiation. The angular accuracy was 0.0010° and the angular resolution was better than 0.01°.

XPS analysis

CuSCN-NP powder was ground in a mortar and pressed against an indium pellet on a sample holder. The sample was analyzed using a Kratos Axis Ultra DLD apparatus at a base pressure of 10−9 mbar, using a Mg k-alpha X-ray source operating at 15 kV accellerating voltage and 5 mA emission current. Charge neutralization was used during the measurement. The wide spectrum was acquired with a fixed pass energy (PE) of 160 eV and step size of 1 eV, while high-resolution spectra of the Cu 2p, Cu LMM, O 1s, N 1s, C 1s, and S 2p regions were measured at PE = 10 eV and step size of 0.1 eV. The valence band region was measured with PE = 10 eV and step size 25 meV. The binding energy (BE) was calibrated assigning BE = 285 eV to the aliphatic C 1s, which results in an estimated uncertainty of 0.2 eV on absolute energy values. Spectra were analyzed using CasaXPS software (version 2.3.19)

SEM and EDS analysis

As synthesized CuSCN-NP were gently attached to conductive carbon tape. After carefully removing the excess, particles were sputter coated with a 10 nm Au layer for imaging and with a carbon layer for EDS analysis. Scanning electron microscopy was performed on a JEOL JSM-6490LA SEM operating in high vacuum with a beam acceleration of 15 kV.

TEM, DLS, and UV–Vis–near-infrared (NIR) analysis

A 1 mg ml−1 suspension of CuSCN-NP in water was obtained by dispersing the powder with the aid of tip ultrasonication (for 20 s at 40% amplitude) and a surfactant. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, 1.3 MDa) and keratin (the protein extracted from wool, using a previously described protocol)45 were used as surfactant. The ratio between CuSCN-NP and surfactant was kept as low as possible to obtain stable suspensions, namely at 10:1 in weight. After letting the suspension settle overnight to remove large particles aggregates, 10 µL were dispensed on a 150 mesh Cu grid coated with an ultrathin carbon film that was plasma treated to increase hydrophilicity. Extra solution was wicked off from the side using filter paper and grids were let to dry overnight before imaging. Two surfactants were used to be able to exclude possible artifacts due to surfactant self assembly. TEM images were recorded on a JEOL JEM-1011 apparatus operating at 100 kV. The same suspensions were used for DLS analysis after further dilution at 0.01 mg ml−1. The DLS spectrum was recorded on a Zetasizer Nano S (Malvern Instruments) at 20 °C. A quartz cuvette was employed with 1 cm optical path. Optical properties of CuSCN (n = 2.2, k = 0.02) used in the modeling, were assumed from literature ref. 46. UV–Vis–NIR absorption spectra of the CuSCN-NP suspensions used for Tauc plot calculation were recorded on a Cary5000 Varian spectrometer.

Preparation of CuSCN@P3HT blends

P3HT was dissolved in chlorobenzene at a concentration of 15 mg mL−1 and the resulting solution was stirred overnight at 70 °C on a hot plate. CuSCN-NP (3.8, 7.5, and 11.3 mg for, respectively, 5 wt%, 10 wt%, and 15 wt% blends, with respect to the P3HT weight) were added each to separated 5 mL portions of the mother P3HT solution and the resulting mixtures were sonicated for 120 s with a tip-sonicator operated at 280 W using a 50% pulse scheme.

Electrochemical characterization

The electrochemical tests were performed in a 2-electrodes configuration using an Autolab PGSTAT302N potentiostat/galvanostat station, equipped with Nova 2.1 (Metrohm) software package. Measurement were performed in a pH = 7, 0.1 M Phosphate buffer solution. A vinyl tape mask has been employed to define an electrochemical active area of 0.2 cm2. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) has been employed to determine the electrochemical response of the electrodes for a potential range going down to −0.2 V vs. RHE for the cathodic reaction and up to 1.9 V vs. RHE for the anodic reaction with a scan rate of 10 mV s−1. The electrodes have been prepared according to the material processing described in the PSC fabrication section. For the P3HT-based electrode the deposition order has been inverted, first depositing gold on a ITO substrate and then spin coating the pure polymer or the CuSCN@P3HT blend. Measurements have been performed in alternating light-dark regime (each 0.05 V) under simulated sunlight by means of A 300 W Xenon light source (Lot Quantum Design, model LS0306), equipped with AM 1.5G filters. In both the tested conditions (pure P3HT and CuSCN@P3HT), illumination direction is from the HTM to the TCO.

EPR measurements

EPR measurements were performed on a Bruker ELEXSYS E580 spectrometer at X-band (9–10 GHz) mounting an ER4118X-MD5 dielectric cavity. Measurements were carried out in dark either at room temperature or at 80 K, employing a liquid-N2 cooling system. Continuous-wave spectra were typically acquired at 20–40 μW microwave power and 0.8 G field modulation amplitude. Spin relaxation experiments were performed at 80 K using a standard echo-decay pulse sequence π/2–t–π–t–det (pulse length 16 ns and 32 ns for π/2 and π pulses, respectively). Echo decays starting at t0 = 140 ns were acquired at the magnetic field corresponding to maximum absorbance and involved echo integration and 2-step phase cycling. All samples were measured under vacuum (~10–5 bar) to avoid disturbances due to paramagnetic O2. In the case of the samples containing P3HT, fixed volumes of the corresponding solutions were inserted into quartz tubes and evaporated under vacuum, followed by tube sealing.

PL measurements

For time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) measurements, the excitation was provided by Coherent Libra regenerative amplifier (50 fs, 1 KHz, 800 nm) seeded by a Coherent Vitesse oscillator (50 fs, 80 MHz). From the fundamental output, 600 nm laser pulses were generated using a Coherent OPerA-Solo optical parametric amplifier. The emission from the samples was collected in backscattering geometry (150° collection angle), and focused by a pair of lenses into a spectrometer. TRPL was collected using an Optronis Optoscope streak camera system, with a ×10 ps temporal resolution.

PSC fabrication and characterization

ITO-coated glass was etched with zinc powder and 2 M aqueous HCl solution for electrode pattern. The ITO substrates were washed with 2% Hellmanex in water, deionized water, iso-propanol, acetone, and iso-propanol sequentially in a sonication bath for ~15 min, followed by O2 plasma cleaning for 10 min. A patterned and cleaned ITO substrate was covered with a ∼10 nm thick SnO2 layer by spin-coating of a diluted SnO2 nanoparticle solution (Alfa Aesar) and annealed at 180 °C for 1 h. The mixed-cation FA/Cs perovskite was prepared by dissolving different molar quantities of 1.21 M PbI2, 1.21 M FAI, 0.24 M PbBr2, and 0.24 M CsBr in 1 L of N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at a volume ratio of 4:1. After stirring for 6 h at room temperature, the perovskite solutions became clear, and they were spin-coated with two steps (the first step at 1000 rpm for 10 s and the second step at 4000 rpm for 30 s). During the second step, 200 μL of anhydrous toluene was quickly dripped at the 15th s. The thin films were then transferred to a hot plate and annealed at 170 °C for 10 min. The whole synthesis process was conducted in the nitrogen-filled glovebox. P3HT-based HTM were deposited on the perovskite film by spin-coating at 2000 rpm. This fabrication process was carried out under controlled atmosphere in a glovebox. Finally, a 75 nm thick layer of gold was thermally evaporated on top of the device at a pressure of 1 × 10-6 mbar to form the back contact. The active area of the complete device results 0.0935 cm-2. SEM images of analogous devices lacking the top metal electrode in top-view and cross-section were obtained on a Zeiss Sigma HD field-emission SEM, working at 5 kV. J–V characteristics were measured with a computer-controlled Keithley 2420 source meter in air without any previous device encapsulation. The simulated Air Mass 1.5 Global (AM 1.5 G) irradiance was provided with a class AAA Newport solar simulator. The light intensity was calibrated with a silicon reference cell with a spectral mismatch factor of 0.99. Scan rates were 0.2 V s-1. The forward scan started from 0 V (the short-circuit condition) to 1.4 V, while reverse scan from 1.4 V to 0 V. The pre-conditional stress was not applied for PV measurements. For degradation test, RH was controlled in a closed glass jar where water was vaporized from a saturated salt solution of potassium chloride. PSC were kept in the glass jar under a RH of 88 ± 1% in dark at room temperature. The IPCE was measured with a home-built setup. IPCE spectra were recorded using the photomodulation spectroscopy setup (Merlin, Oriel) with monochromatic light from a Xenon lamp calibrated with a Newport UV-818 photodiode. The illumination intensity was calibrated using an unfiltered certified Si reference diode (area = 4 cm2, Newport) to be 100 mW cm−2 (typical spectral mismatch factor of 1.01 for solar cells based on CH3NH3PbI3).

Kelvin probe measurements

Kelvin probe microscopy measurements on CuSCN-NP were carried out in ambient air with an atomic force microscope MFP-3D by Asylum Research (Oxford Instruments, UK). A probe AYELEC.02 was used, with nominal cantilever resonance frequency of 300 kHz, and tip coated with 25 nm thick Ti/Ir film. The scan was two-pass, with surface potential measured during the second pass at elevated height (tipically 100 nm). The work function of the tip was first determined, by measuring V on highly oriented pyrolitic graphite (HOPG), whose work function was assumed to be 4.40 eV. Measurements were carried out both on sample powder, spread on a Silicon wafer, and on a thick (bulk) layer of sample powder, pressed to form a solid pellet, finding consistent values, within the uncertainty (±100 mV). The obtained value resulted from averaging the means from N = 4 images of typical 5 µm scan size, in different sample locations. Kelvin probe measurements on solar cells were carried out on a KP Technology single point system, equipped with a 2 mm gold coated tip on samples stored for 28 days in humid (RH = 88.1%) and dry conditions. Each measurement was left to stabilize for 5 min after which the measured work function was regarded as stable. The samples for KP were prepared by spin-coating the different HTM directly onto FTO substrates following the same procedure used for depositing them on top of the perovskite layer during PSC fabrication.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Manser, J. S., Saidaminov, M. I., Christians, J. A., Bakr, O. M. & Kamat, P. V. Making and breaking of lead halide perovskites. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 330–338 (2016).

Leijtens, T. et al. Towards enabling stable lead halide perovskite solar cells; interplay between structural, environmental, and thermal stability. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 11483–11500 (2017).

Mosconi, E., Azpiroz, J. M. & De Angelis, F. Ab initio molecular dynamics simulations of methylammonium lead iodide perovskite degradation by water. Chem. Mater. 27, 4885–4892 (2015).

Lu, Y.-B. et al. Light enhanced moisture degradation of perovskite solar cell material CH3NH3PbI3. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 27469–27474 (2019).

Li, F. & Liu, M. Recent efficient strategies for improving the moisture stability of perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 15447–15459 (2017).

Ono, L. K., Qi, Y. & Liu, S. Progress toward stable lead halide perovskite solar cells. Joule 2, 1961–1990 (2018).

Bai, S. et al. Planar perovskite solar cells with long-term stability using ionic liquid additives. Nature 571, 245–250 (2019).

Fu, Q. et al. Recent progress on the long-term stability of perovskite solar cells. Adv. Sci. 5, 1700387 (2018).

Tachibana, Y., Vayssieres, L. & Durrant, J. R. Artificial photosynthesis for solar water-splitting. Nat. Photon. 6, 511–518 (2012).

Meyer, T. J. Chemical approaches to artificial photosynthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 22, 163–170 (1989).

Hisatomi, T., Kubota, J. & Domen, K. Recent advances in semiconductors for photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 7520–7535 (2014).

Osterloh, F. E. Inorganic nanostructures for photoelectrochemical and photocatalytic water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 2294–2320 (2013).

Kung, P.-K. et al. A review of inorganic hole transport materials for perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1800882 (2018).

Arora, N. et al. Perovskite solar cells with CuSCN hole extraction layers yield stabilized efficiencies greater than 20%. Science (80-.) 358, 768–771 (2017).

Vo, T.-G., Chiu, J.-M., Tai, Y. & Chiang, C.-Y. Turnip-inspired BiVO4/CuSCN nanostructure with close to 100% suppression of surface recombination for solar water splitting. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 185, 415–424 (2018).

Yang, I. S. et al. Formation of pristine CuSCN layer by spray deposition method for efficient perovskite solar cell with extended stability. Nano Energy 32, 414–421 (2017).

Darr, J. A., Zhang, J., Makwana, N. M. & Weng, X. Continuous hydrothermal synthesis of inorganic nanoparticles: applications and future directions. Chem. Rev. 117, 11125–11238 (2017).

Toušek, J. et al. Comparison of the electron work function, hole concentration and exciton diffusion length for P3HT and PT prepared by thermal or acid cleavage. Solid. State. Electron. 116, 111–118 (2016).

Nia, N. Y., Matteocci, F., Cina, L. & Di Carlo, A. High-efficiency perovskite solar cell based on poly(3-Hexylthiophene): influence of molecular weight and mesoscopic scaffold layer. ChemSusChem 10, 3854–3860 (2017).

Gatti, T. et al. Interfacial morphology addresses performance of perovskite solar cells based on composite hole transporting materials of functionalized reduced graphene oxide and P3HT. Sol. RRL 2, 1800013 (2018).

Gatti, T. et al. Boosting perovskite solar cells performance and stability through doping a poly‐3(hexylthiophene) hole transporting material with organic functionalized carbon nanostructures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 7443–7453 (2016).

Righetto, M. et al. Coupling halide perovskites with different materials: From doping to nanocomposites, beyond photovoltaics. Prog. Mater. Sci. 110, 100639 (2020).

Fox, M. & Ispasoiu, R. in Springer Handbook of Electronic and Photonic Materials (eds. Kasap, S. & Capper, P.) Vol. 1 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Liu, F. et al. Colloidal synthesis of air-stable alloyed CsSn1–xPbxI3 perovskite nanocrystals for use in solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16708–16719 (2017).

Kamiya, T., Nomura, K., Hirano, M. & Hosono, H. Electronic structure of oxygen deficient amorphous oxide semiconductor a-InGaZnO4–x: optical analyses and first-principle calculations. Phys. Status Solidi C 5, 3098–3100 (2008).

Urbach, F. The long-wavelength edge of photographic sensitivity and of the electronic absorption of solids. Phys. Rev. 92, 1324 (1953).

Aldakov, D. et al. Properties of electrodeposited CuSCN 2D layers and nanowires influenced by their mixed domain structure. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 16095–16103 (2014).

Wijeyasinghe, N. et al. Copper(I) thiocyanate (CuSCN) hole-transport layers processed from aqueous precursor solutions and their application in thin-film transistors and highly efficient organic and organometal halide perovskite solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1701818 (2017).

Biesinger, M. C. Advanced analysis of copper X-ray photoelectron spectra. Surf. Interface Anal. 49, 1325–1334 (2017).

Srinivasan, V. & Walton, R. A. X-ray photoelectron spectra of inorganic molecules.: XX. Observations concerning the sulfur 2p binding energies in metal complexes of thiourea. Inorganica Chim. Acta 25, L85–L86 (1977).

Xie, Y. et al. Copper sulfide nanocrystals with tunable composition by reduction of covellite nanocrystals with Cu + ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 17630–17637 (2013).

Padmavathy, V., Sankar, S. & Ponnuswamy, V. Influence of thiourea on the synthesis and characterization of chemically deposited nano structured zinc sulphide thin films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron 29, 7739–7749 (2018).

Egerton, R. F. Mechanisms of radiation damage in beam-sensitive specimens, for TEM accelerating voltages between 10 and 300 kV. Microsc. Res. Tech. 75, 1550–1556 (2012).

Bellani, S. et al. Reversible P3HT/oxygen charge transfer complex identification in thin films exposed to direct contact with water. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 6291–6299 (2014).

Sperlich, A. et al. Reversible and irreversible interactions of Poly(3-hexylthiophene) with oxygen studied by spin-sensitive methods. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 13513–13518 (2011).

Topolovsek, P. et al. Functionalization of transparent conductive oxide electrode for TiO2-free perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 11882–11893 (2017).

Mabrouk, S. et al. Synergistic engineering of hole transport materials in perovskite solar cells. InfoMat inf2.12062 https://doi.org/10.1002/inf2.12062 (2019).

Montgomery, A. et al. Solution‐processed copper (I) thiocyanate (CuSCN) for highly efficient CdSe/CdTe thin‐film solar cells. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. pip 3136 https://doi.org/10.1002/pip.3136 (2019).

Narasimha, K. T. et al. Ultralow effective work function surfaces using diamondoid monolayers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 267 (2015).

Hintz, H., Peisert, H., Egelhaaf, H.-J. & Chassé, T. Reversible and irreversible light-induced p-doping of P3HT by oxygen studied by photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS/UPS). J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 13373–13376 (2011).

Jørgensen, M., Norrman, K. & Krebs, F. C. Stability/degradation of polymer solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 92, 686–714 (2008).

Jørgensen, M. et al. Stability of polymer solar cells. Adv. Mater. 24, 580–612 (2012).

Gruar, R. I., Tighe, C. J. & Darr, J. A. Scaling-up a confined jet reactor for the continuous hydrothermal manufacture of nanomaterials. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 5270–5281 (2013).

Wang, Z. D., Yoshida, M. & George, B. Theoretical study on the thermal decomposition of thiourea. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1017, 91–98 (2013).

Cataldi, P. et al. Keratin-graphene nanocomposite: transformation of waste wool in electronic devices. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 12544–12551 (2019).

Ezealigo, B. N. et al. A study on solution deposited CuSCN thin films: Structural, electrochemical, optical properties. Arab. J. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.04.013 (2017).

Kim, M. et al. Band-tail transport of CuSCN: origin of hole extraction enhancement in organic photovoltaics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 2856–2861 (2016).

Acknowledgements

F.L., S.G., and G.M. acknowledge the “Centro Studi di Economia e Tecnica dell’Energia Giorgio Levi Cases” of the University of Padova through the AMON-RA project for financial support. M.K. acknowledges funding from EU Horizon 2020 via a Marie Sklodowska Curie Fellowship (Project No. 797546). T.G. and S.G. thank the DFG for financial support via the GRK (Research Training Group) 2204 “Substitute Materials for Sustainable Energy Technologies”. T.G. further acknowledges the “Fonds der Chemischen Industrie” of the Verband der Chemischen Industrie e.V. for a material cost allowance financial support. Prof. Jawwad Darr (UCL, London) is gratefully acknowledged for the possibility to perform the CuSCN synthesis on his continuous flow hydrothermal synthesis reactor. We sincerely thank Dr. Marcello Righetto and Prof. Tze-Chien Sum of the National University of Singapore for time-resolved photoluminescence measurements and analysis. We also thank Dr. Peter Topolovsek (CNST@IIT Milano) for the help with KP measurements on pn junctions. We sincerely acknowledge Dr. James Ball (University of Oxford) and Prof. Lorenzo Franco (University of Padova) for the insightful discussion and suggestions on EPR data interpretation, Dr. Rosaria Brescia (Electron Microscopy facility, IIT) for SAED tests during the manuscript revision process and Mr. Sergio Marras (Materials Characterization Facility, IIT) for XRD pattern indexing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.L. and T.G conceived the idea of the work, designed and managed the project and the experiments. N.D. prepared the CuSCN-NP and performed XRD and UV–Visible characterization of the CuSCN-NP. G.P. characterized the CuSCN-NP with SEM-EDX, TEM and DLS. M. Serri and M.P. performed XPS measurements on CuSCN-NP. M. Salerno performed KP measurments on CuSCN-NP. N.D. and M.K. prepared the P3HT blends. A.A. and A.M. designed the experiment and performed the WS splitting test. R.S. performed wettability measurments. M.K. fabricated the solar cells and performed the endurance tests. M.K. performed KP characterization. E.C. performed EPR measurements. F.L., A.R., and T.G. analyzed the data. F.L. and T.G. wrote the manuscript. S.G., G.M., F.D.F., and A.P. revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to finalizing the draft and gave their final assessment to the submitted paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Primary handling editor: John Plummer

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, M., Alfano, A., Perotto, G. et al. Moisture resistance in perovskite solar cells attributed to a water-splitting layer. Commun Mater 2, 6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-020-00104-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-020-00104-z

This article is cited by

-

Advanced materials to overcome the challenges in the fabrication of stable and efficient perovskite solar cells by additive engineering: a review

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

-

Reconfiguring perovskite interface via R4NBr addition reaction toward efficient and stable FAPbI3-based solar cells

Science China Chemistry (2022)

-

Moisture tolerant solar cells by encapsulating 3D perovskite with long-chain alkylammonium cation-based 2D perovskite

Communications Materials (2021)