Abstract

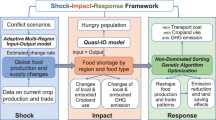

Disasters resulting from climate change and extreme weather events adversely impact crop and livestock production. While the direct impacts of these events on productivity are generally well known, the indirect supply-chain repercussions (spillovers) are still unclear. Here, applying an integrated modelling framework that considers economic and physical factors, we estimate spillovers in terms of social impacts (for example, loss of job and income) and health impacts (for example, nutrient availability and diet quality) resulting from disruptions in food supply chains, which cascade across regions and sectors. Our results demonstrate that post-disaster impacts are wide-ranging and diverse owing to the interconnected nature of supply chains. We find that fruit, vegetable and livestock sectors are the most affected, with effects flowing on to other non-food production sectors such as transport services. The ability to cope with disasters is determined by socio-demographic characteristics, with communities in rural areas being most affected.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data used in this study are stored in the Australian IELab (ielab.info), and are accessible from the authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Codes used in this study are stored in the Australian IELab (ielab.info), and are accessible from the authors upon request.

References

Schmidhuber, J. & Tubiello, F. N. Global food security under climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 19703–19708 (2007).

Rosenzweig, C., Iglesias, A., Yang, X., Epstein, P. R. & Chivian, E. Climate change and extreme weather events; implications for food production, plant diseases, and pests. Glob. Change Hum. Health 2, 90–104 (2001).

Wheeler, T. & von Braun, J. Climate change impacts on global food security. Science 341, 508–513 (2013).

Myers, S. S. et al. Climate change and global food systems: potential impacts on food security and undernutrition. Annu. Rev. Public Health 38, 259–277 (2017).

Rosenzweig, C., Tubiello, F. N., Goldberg, R., Mills, E. & Bloomfield, J. Increased crop damage in the US from excess precipitation under climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 12, 197–202 (2002).

Giannini, T. C. et al. Pollination services at risk: bee habitats will decrease owing to climate change in Brazil. Ecol. Modell. 244, 127–131 (2012).

Vanbergen, A. J., Initiative, t. I. P. Threats to an ecosystem service: pressures on pollinators. Front. Ecol. Environ. 11, 251–259 (2013).

Veron, J. E. Mass extinctions and ocean acidification: biological constraints on geological dilemmas. Coral Reefs 27, 459–472 (2008).

St-Pierre, N., Cobanov, B. & Schnitkey, G. Economic losses from heat stress by US livestock industries. J. Dairy Sci. 86, E52–E77 (2003).

Nicholls, N. Increased Australian wheat yield due to recent climate trends. Nature 387, 484–485 (1997).

Leisner, C. P. Climate change impacts on food security-focus on perennial cropping systems and nutritional value. Plant Sci. 293, 110412 (2020).

FAO. Right to healthy food should be a key dimension for Zero Hunger, says FAO DG. https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/Right-to-healthy-food-should-be-a-key-dimension-for-Zero-Hunger-says-FAO-DG/en(2019).

Rivera-Ferre, M. G. et al. Local agriculture traditional knowledge to ensure food availability in a changing climate: revisiting water management practices in the Indo-Gangetic Plains. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 40, 965–987 (2016).

Alam, M. M., Siwar, C., Talib, B. A. & Wahid, A. N. M. Climatic changes and vulnerability of household food accessibility. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 9, 387–401 (2017).

Burchi, F. & De Muro, P. From food availability to nutritional capabilities: advancing food security analysis. Food Policy 60, 10–19 (2016).

Burchi, F., Fanzo, J. & Frison, E. The role of food and nutrition system approaches in tackling hidden hunger. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8, 358–373 (2011).

NHMRC. Australian Dietary Guidelines https://eatforhealth.govcms.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/n55_australian_dietary_guidelines.pdf (2013).

Fiedler, J. L. Food crop production, nutrient availability, and nutrient intakes in Bangladesh: exploring the agriculture–Nutrition Nexus with the 2010 household income and expenditure survey. Food Nutr. Bull. 35, 487–508 (2014).

Tapsell, L. C., Neale, E. P., Satija, A. & Hu, F. B. Foods, nutrients, and dietary patterns: Interconnections and implications for dietary guidelines. Adv. Nutr. 7, 445–454 (2016).

Monteiro, C. A. et al. Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 22, 936–941 (2019).

Hughes, L., Steffen, W., Rice, M. & Pearce, A. Feeding a Hungry Nation: Climate Change, Food and Farming in Australia (Climate Council of Australia, Sydney, 2015).

Howden, S. M., Schroeter, S. & Crimp, S. in Four Degrees of Global Warming: Australia in a Hot World (ed. P Christoff) (Earthscan, Routledge 2014).

Reisinger, A. et al. in Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the AR5 of the IPCC (eds V. R. Barros et al.) Ch. 25, 1371–1438 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Luo, Q., Bellotti, W., Williams, M. & Bryan, B. Potential impact of climate change on wheat yield in South Australia. Agric. For. Meteorol. 132, 273–285 (2005).

Cullen, B. et al. Climate change effects on pasture systems in south-eastern Australia. Crop Pasture Sci. 60, 933–942 (2009).

Turner, N. C., Molyneux, N., Yang, S., Xiong, Y.-C. & Siddique, K. H. Climate change in south-west Australia and north-west China: challenges and opportunities for crop production. Crop Pasture Sci. 62, 445–456 (2011).

Anwar, M. R. et al. Climate change impacts on phenology and yields of five broadacre crops at four climatologically distinct locations in Australia. Agric. Syst. 132, 133–144 (2015).

Ugalde, D., Brungs, A., Kaebernick, M., McGregor, A. & Slattery, B. Implications of climate change for tillage practice in Australia. Soil Tillage Res. 97, 318–330 (2007).

Cowan, T. et al. More frequent, longer, and hotter heat waves for Australia in the twenty-first century. J. Clim. 27, 5851–5871 (2014).

Walsh, K. J. & Ryan, B. F. Tropical cyclone intensity increase near Australia as a result of climate change. J. Clim. 13, 3029–3036 (2000).

Sovacool, B. K. & Brown, M. A. Scaling the policy response to climate change. Policy Soc. 27, 317–328 (2009).

Gitz, V. & Meybeck, A. Risks, vulnerabilities and resilience in a context of climate change. Building resilience for adaptation to climate change in the agriculture sector: https://www.fao.org/3/i3084e/i3084e.pdf 19–36 (2012).

Lenzen, M. et al. Compiling and using input–output frameworks through collaborative virtual laboratories. Sci. Total Environ. 485, 241–251 (2014).

ABS. 6530.0 - Household Expenditure Survey, Australia: Summary of Results, 2015–16. Report No. http://abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/6530.0Main%20Features22015-16?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=6530.0&issue=2015-16&num=&view= (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 2017).

Hogan, L. Food Demand in Australia: Trends and Issues 2018 (Australian Government Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, 2018).

Lewis, M., McNaughton, S. A., Rychetnik, L., Chatfield, M. D. & Lee, A. J. Dietary intake, cost and affordability by socioeconomic group in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 13315 (2021).

NHMRC. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand https://www.nrv.gov.au/ (2006).

Olstad, D. L. et al. Are dietary inequalities among Australian adults changing? A nationally representative analysis of dietary change according to socioeconomic position between 1995 and 2011–13. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 15, 30 (2018).

ABS. 6503.0 - Household Expenditure Survey and Survey of Income and Housing, User Guide, Australia, 2015-16: Expenditure Comparison, https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/6503.0~2015-16~Main%20Features~Expenditure%20comparison~10003 (2018).

Bartos, S., Balmford, M., Karolis, A., Swansson, J. & Davey, A. Resilience in the Australian Food Supply Chain (Sapere Research Group, Canberra, Australia, 2011).

Moore, A. D. & Ghahramani, A. Climate change and broadacre livestock production across southern Australia. 1. Impacts of climate change on pasture and livestock productivity, and on sustainable levels of profitability. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 1440–1455 (2013).

Hughes, L., Steffen, W., Rice, M., & Pearce, A. Feeding a hungry nation: climate change, food and farming in Australia. (Climate Council of Australia, Sydney, 2015).

MDBA. The Murray–Darling Basin https://www.mdba.gov.au/sites/default/files/pubs/MDBA-Overview-Brochure.pdf (2019).

ABS. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian-statistical-geography-standard-asgs-edition-3 (2018).

ABS. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS). https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian-statistical-geography-standard-asgs-edition-3. 2018.

Green, D., Jackson, S. & Morrison, J. Risks from Climate Change to Indigenous Communities in the Tropical North of Australia (Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, Canberra, 2009).

Onwutuebe, C. J. Patriarchy and women vulnerability to adverse climate change in Nigeria. Sage Open 9, 2158244019825914 (2019).

Adger, W. N. & Kelly, P. M. Social vulnerability to climate change and the architecture of entitlements. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 4, 253–266 (1999).

NSW DPI. Central West Region Pilot Area: Horticulture & Viticulture Profile https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/457590/Horticulture-viticulture-profile-central-west-region.pdf (2012).

NSW DPI. Central West Region Pilot Area: Agricultural Profile https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/457588/Agricultural-profile-central-west-region.pdf (2012).

Dairy Australia. Australian Dairy Industry In Focus 2018 https://www.dairyaustralia.com.au/publications/australian-dairy-industry-in-focus-2018?id=B81A5CE26AAE4C0F898E8F3BFF0014D9 (2018).

Barbut, S. Effects of milk powder and its components on texture, yield, and color of a lean poultry meat model system. Poultry Sci. 89, 1320–1324 (2010).

Jonas, J. J. Utilization of dairy ingredients in other foods. J. Milk Food Technol. 36, 323–332 (1973).

Food Standards Australia & New Zealand. AUSNUT 2011–2013 http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/ausnut/Pages/default.aspx (2019).

NSW Government. Climate change impacts on our alpine areas https://www.climatechange.environment.nsw.gov.au/alpine (2022).

WHO. Vulnerability: Conceptual Brief https://apps.who.int/disasters/repo/13849_files/n/vulnerability_concept_brief.pdf (2022).

Hinkel, J. “Indicators of vulnerability and adaptive capacity”: towards a clarification of the science–policy interface. Glob. Environ. Chang. 21, 198–208 (2011).

NRV. Recommendations to Reduce Chronic Disease Risk https://www.nrv.gov.au/chronic-disease/summary (2017).

Trostle, R. Global Agricultural Supply and Demand: Factors Contributing to the Recent Increase in Food Commodity Prices (Diane Publishing, 2010).

UNDRR. Vulnerability https://www.undrr.org/terminology/vulnerability (2022).

Dilley, M. & Boudreau, T. E. Coming to terms with vulnerability: a critique of the food security definition. Food Policy 26, 229–247 (2001).

Green, R. et al. The effect of rising food prices on food consumption: systematic review with meta-regression. Brit. Med. J. 346, f3703 (2013).

ABS. 1410.0 - Data by Region, 2013-18 - Persons born overseas, Australia, State and Territory, Statistical Area Levels 2-4, Greater Capital City Statistical Area, 2011-2018 https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/1410.02013-18?OpenDocument (2019).

ABS. 3238.0.55.001 - Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2016 https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3238.0.55.001 (2018).

The Guardian. ‘Critical’: Parts of Regional NSW Set to Run Out of water by November https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/sep/15/parts-of-regional-nsw-set-to-run-out-of-water-by-november (2019).

ABS. 3412.0 - Migration, Australia, 2017–18 https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3412.0Main%20Features22017-18 (2019).

ABS. 6524.0.55.002 - Estimates of Personal Income for Small Areas, 2011–2016 https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6524.0.55.002 (2018).

Darmon, N. & Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr. Rev. 73, 643–660 (2015).

Brooks, R. C., Simpson, S. & Raubenheimer, D. The price of protein: combining evolutionary and economic analysis to understand excessive energy consumption. Obesity Rev. 11, 887–894 (2010).

IPCC Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems (eds Shukla, P. R. et al) (2019).

Dean, W. R. & Sharkey, J. R. Rural and urban differences in the associations between characteristics of the community food environment and fruit and vegetable intake. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 43, 426–433 (2011).

Raubenheimer, D. & Simpson, S. J. Nutritional ecology and human health. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 36, 603–626 (2016).

Joske, R. & Lenzen, M. Intersectoral and Inter-state trade Links in Australia (The University of Sydney Integrated Sustainability Analysis, Sydney, 2006).

ABS. 5220.0 - Australian National Accounts: State Accounts, 2018–19 https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/5220.02018-19?OpenDocument (2019).

Lenzen, M. et al. New multi-regional input–output databases for Australia—enabling timely and flexible regional analysis. Econ. Syst. Res. 29, 275–295 (2017).

Nicholson, C. F., He, X., Gómez, M. I., Gao, H. & Hill, E. Environmental and economic impacts of localizing food systems: the case of dairy supply chains in the northeastern United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 12005–12014 (2015).

Shadbolt, N. M. & Apparao, D. Factors influencing the dairy trade from New Zealand. Int. Food Agribusiness Manag. Rev. 19 (B), 241–255 (2016).

FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World http://www.fao.org/3/ca5162en/ca5162en.pdf (2018).

AIHW. Australia’s Health 2018 https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/b1be8be0-4080-4be7-bf67-d6bec2c5829c/aihw-aus-221-chapter-4-9.pdf.aspx (2018).

Généreux, M., Lafontaine, M. & Eykelbosh, A. From science to policy and practice: a critical assessment of knowledge management before, during, and after environmental public health disasters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 587 (2019).

National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/emergency/files/national-disaster-risk-reduction-framework.pdf (Department of Home Affairs, Canberra, 2018).

DFAT. Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience https://www.dfat.gov.au/development/topics/investment-priorities/building-resilience/drr/disaster-risk-reduction-and-resilience (2022).

Rai, R. K., Kumar, S., Sekher, M., Pritchard, B. & Rammohan, A. A life-cycle approach to food and nutrition security in India. Public Health Nutr. 18, 944–949 (2015).

Pelletier, N. Life cycle thinking, measurement and management for food system sustainability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 7515–7519 (2015).

Soussana, J.-F. Research priorities for sustainable agri-food systems and life cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 73, 19–23 (2014).

Lundie, S. & Peters, G. M. Life cycle assessment of food waste management options. J. Clean. Prod. 13, 275–286 (2005).

Carlsson-Kanyama, A., Ekström, M. P. & Shanahan, H. Food and life cycle energy inputs: consequences of diet and ways to increase efficiency. Ecol. Econ. 44, 293–307 (2003).

Pan, X. & Kraines, S. Environmental input–output models for life-cycle analysis. Environ. Resour. Econ. 20, 61–72 (2001).

Joshi, S. Product environmental life-cycle assessment using input–output techniques. J. Ind. Ecol. 3, 95–120 (2001).

Hendrickson, C., Horvath, A., Joshi, S. & Lave, L. Economic input–output models for environmental life-cycle assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32, 184A–191A (1998).

Goodstein, E. S. in Economics and the Environment (Prentice Hall, 1995).

Leontief, W. Quantitative input and output relations in the economic system of the United States. Rev. Econ. Stat. 18, 105–125 (1936).

Leontief, W. The Structure of the American Economy, 1919–1939 (Oxford University Press, 1941).

Dietzenbacher, E. et al. Input–output analysis: the next 25 years. Econ. Syst. Res. 25, 369–389 (2013).

Duchin, F. Industrial input–output analysis: implications for industrial ecology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 851–855 (1992).

Dixon, R. Inter-industry transactions and input–output analysis. Aust. Econ. Rev. 29, 327–336 (1996).

UN. System of National Accounts 2008 (United Nations, European Commission, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, World Bank, New York, USA, 2009).

UN. Handbook of Input–Output Table Compilation and Analysis (United Nations, 1999).

Leontief, W. & Ford, D. Environmental repercussions and the economic structure: an input-output approach. Rev. Econ. Stat. 52, 262–271 (1970).

Forssell, O. & Polenske, K. R. Introduction: input–output and the environment. Econ. Syst. Res. 10, 91–97 (1998).

Tukker, A. et al. Environmental and resource footprints in a global context: Europe’s structural deficit in resource endowments. Glob. Environ. Chang. 40, 171–181 (2016).

Lenzen, M. et al. International trade drives biodiversity threats in developing nations. Nature 486, 109–112 (2012).

Feng, K., Chapagain, A. K., Suh, S., Pfister, S. & Hubacek, K. Comparison of bottom-up and top-down approaches to calculating the water footprints of nations. Econ. Syst. Res. 23, 371–385 (2011).

Gómez-Paredes, J. et al. Consuming childhoods: an assessment of child labor’s role in Indian production and global consumption. J. Ind. Ecol. 20, 611–622 (2016).

Alsamawi, A., Murray, J., Lenzen, M., Kanemoto, K. & Moran, D. A novel approach to quantitative accounting of income inequality. PLoS ONE 9, e110881 (2014).

Leontief, W. W. & Strout, A. A. in Structural Interdependence and Economic Development (ed. Barna, T.) 119–149 (Macmillan, 1963).

Isard, W. Interregional and regional input–output analysis, a model of a space economy. Rev. Econ. Stat. 33, 318–328 (1951).

Tukker, A. & Dietzenbacher, E. Global multiregional input–output frameworks: an introduction and outlook. Econ. Syst. Res. 25, 1–19 (2013).

Wiedmann, T. A review of recent multi-region input–output models used for consumption-based emission and resource accounting. Ecol. Econ. 69, 211–222 (2009).

Duchin, F., Levine, S. H. & Strømman, A. H. Combining multiregional input–output analysis with a world trade model for evaluating scenarios for sustainable use of global resources, part I: conceptual framework. J. Ind. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12303 (2015).

Guan, D. & Hubacek, K. Assessment of regional trade and virtual water flows in China. Ecol. Econ. 61, 159–170 (2007).

Lenzen, M. Understanding virtual water flows—a multi-region input–output case study of Victoria. Water Resour. Res. 45, W09416 (2009).

Dietzenbacher, E. & Velázquez, E. Analysing Andalusian virtual water trade in an input–output framework. Reg. Stud. 41, 1–12 (2007).

Okuyama, Y. Economic modeling for disaster impact analysis: past, present, and future. Econ. Syst. Res. 19, 115–124 (2007).

Okuyama, Y. & Santos, J. R. Disaster impact and input–output analysis. Econ. Syst. Res. 26, 1–12 (2014).

Rose, A., Benavides, J., Chang, S. E., Szczesniak, P. & Lim, D. The regional economic impact of an earthquake: direct and indirect effects of electricity lifeline disruptions. J. Reg. Sci. 37, 437–458 (1997).

Rose, A. & Lim, D. Business interruption losses from natural hazards: conceptual and methodological issues in the case of the Northridge earthquake. Glob. Environ. Chang. B 4, 1–14 (2002).

Faturay, F., Sun, Y.-Y. & Lenzen, M. Using virtual laboratories for disaster analysis—a case study of Taiwan. Econ. Syst. Res 32, 58–83 (2019).

MacKenzie, C. A., Santos, J. R. & Barker, K. Measuring changes in international production from a disruption: case study of the Japanese earthquake and tsunami. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 138, 293–302 (2012).

Arto, I., Andreoni, V. & Rueda Cantuche, J. M. Global impacts of the automotive supply chain disruption following the Japanese earthquake of 2011. Econ. Syst. Res. 27, 306–323 (2015).

Schulte in den Bäumen, H., Moran, D., Lenzen, M., Cairns, I. & Steenge, A. How severe space weather can disrupt global supply chains. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 2749–2759 (2014).

Lenzen, M. et al. Economic damage and spillovers from a tropical cyclone. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 137–151 (2019).

Li, J., Crawford‐Brown, D., Syddall, M. & Guan, D. Modeling imbalanced economic recovery following a natural disaster using input–output analysis. Risk Anal. 33, 1908–1923 (2013).

Schulte in den Bäumen, H., Többen, J. & Lenzen, M. Labour forced impacts and production losses due to the 2013 flood in Germany. J. Hydrol. 527, 142–150 (2015).

Lenzen, M. et al. Economic damage and spillovers from a tropical cyclone. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 137–151 (2019).

Steenge, A. E. & Bočkarjova, M. Thinking about imbalances in post-catastrophe economies: an input–output based proposition. Econ. Syst. Res. 19, 205–223 (2007).

Wiedmann, T. An Input–Output Virtual Laboratory in practice—survey of uptake, usage and applications of the first operational IELab. Econ. Syst. Res. 29, 296–312 (2017).

Lenzen, M. et al. Compiling and using input–output frameworks through collaborative virtual laboratories. Sci. Total Environ. 485–486, 241–251 (2014).

Lenzen, M. et al. New multi-regional input–output databases for Australia—enabling timely and flexible regional analysis. Econ. Syst. Res. 29, 275–295 (2017).

ABS. Australian National Accounts: Input–Output Tables Report No. 5209.0 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 2019).

ABS. Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product Report No. 5206 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 2019).

ABS. Australian National Accounts—State Accounts Report No. 5220.0 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 2019).

ABS. Business Register Counts Report No. 8165.0 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 2019).

ABS. Census of Population and Housing Report No. (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 2019).

ABS. Household Expenditure Survey—Detailed Expenditure Items, Confidentialised Unit Record File Report No. 6535.0 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 2019).

ABS. Value of Agricultural Commodities Produced, Australia Report No. 7503.0 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 2019).

ABS. Australian Industry Report No. 8155.0 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 2019).

ABS. Mining Operations Australia Report No. 8415.0 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 2019).

ABS. 2901.0 - Census of Population and Housing: Census Dictionary, 2016 https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2901.0Chapter4402016 (2016).

ABS. 2900.0 - Census of Population and Housing: Understanding the Census and Census Data, Australia, 2016 https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2900.0~2016~Main%20Features~INCP%20Total%20Personal%20Income%20(weekly)~10059 (2017).

ABS. 2900.0 - Census of Population and Housing: Understanding the Census and Census Data, Australia, 2016: Tenure-Type https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2900.0main+features101362016 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment via the Human Health and Social Impact Node, Australian Research Council (projects DP0985522, DP130101293, DP190102277, LE160100066, DP200102585, DP200103005, LP200100311 and IH190100009), the National eResearch Collaboration Tools and Resources project, through the Industrial Ecology Virtual Laboratory infrastructure VL 201 and the University of Sydney SOAR prize. We thank N. Herold for providing expert advice on design of scenarios for assessing the impact of climate change and extreme weather events, J. Pardoe for her ongoing advice in workshops and on draft versions of this report, L. Merrington for his input in classification of food sectors into ADG groups, S. Juraszek for expertly managing the computational requirements, and C. Jarabak and C. Mora for help with collecting information.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Lenzen, A.M., K.B. and S.B. conceptualized and planned the paper; A.M., M. Lenzen, K.B., N.L., J.F., A.L., S.B., A.G. and M. Li, coordinated the construction of the gamma matrix and data collection; M. Li, M. Lenzen and A.M. processed data and produced figures; A.M., M. Lenzen, N.L., J.F., A.L., D.R., S.B., M.P., M. Li and K.B. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Food thanks Cheikh Mbow, Ray Taylor and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains supplementary notes, figures, discussion and references.

Source data

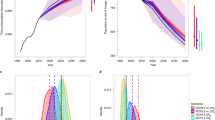

Source Data Fig. 1

Excel file with data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Excel file with data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Excel file with data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Excel file with data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Excel file with data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Malik, A., Li, M., Lenzen, M. et al. Impacts of climate change and extreme weather on food supply chains cascade across sectors and regions in Australia. Nat Food 3, 631–643 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00570-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00570-3

This article is cited by

-

The economic commitment of climate change

Nature (2024)

-

Wish You Were Here? The Economic Impact of the Tourism Shutdown from Australia’s 2019-20 ‘Black Summer’ Bushfires

Economics of Disasters and Climate Change (2024)

-

A bibliometric review of climate change cascading effects: past focus and future prospects

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2023)