Abstract

African swine fever (ASF) is a fatal and highly infectious haemorrhagic disease that has spread to all provinces in China—the world’s largest producer and consumer of pork. Here we use an input–output model, partial equilibrium theory and a substitution indicator approach for handling missing data to develop a systematic valuation framework for assessing economic losses caused by ASF outbreaks in China between August 2018 and July 2019. We show that the total economic loss accounts for 0.78% of China’s gross domestic product in 2019, with impacts experienced in almost all economic sectors through links to the pork industry and a substantial decrease in consumer surplus. Scenario analyses demonstrate that the worst cases of pig production reduction and price increase would trigger 1.4% and 2.07% declines in gross domestic product, respectively. These findings demonstrate an urgent need for rapid ASF containment and prevention measures to avoid future outbreaks and economic declines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

African swine fever (ASF) is classified by the World Organisation for Animal Health as a List A disease, with a mortality of up to 100%1,2,3. The latest large outbreak of ASF was reported in China, the world’s biggest producer and consumer of pork, in August 2018 and has killed millions of pigs4. Due to the absence of effective vaccines and treatment and proper sanitary and hygiene practices, eradication of the disease presents a major challenge5,6. Particularly in China, a large proportion of pigs are kept on small-sized farms which lack the capacity to prevent infection and to control pig diseases. This makes eradication of ASF very difficult in China. Since the onset of the latest outbreak, huge efforts have been made to prevent and control the rapid spread of the disease, including a strict stamping-out policy that involves delineating quarantine zones for infected areas and the rigorous culling of infected herds7,8,9. These measures inevitably cause large economic losses and affect many people and related industries10,11.

This study therefore aims to propose a valuation framework for assessing the extent of both the direct and indirect financial losses caused by the ASF outbreaks in China over the period from August 2018 to July 2019. Although this ASF epidemic has not completely ended in China when we revised the paper (July 2021), we chose to look at this 1 yr period as an estimation interval based on the following consideration: the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) was identified in Wuhan, China at the end of 2019 and has since spread rapidly across the whole of China and the world. The COVID-19 pandemic is not only a public health crisis but has also severely affected the Chinese economy. Thus, only examining the period before the outbreak of the coronavirus allows us to focus on the impact of the ASF epidemic, and our findings will help further studies to disentangle the economic impacts of these two overlapping epidemics.

We then develop an economic loss assessment framework of animal epidemics that integrates a substitution indicator estimation, an input–output model and partial equilibrium theory. We estimate the direct economic losses to China’s swine industry by considering three aspects: the financial losses from the culling and removal of infected carcasses, the financial losses from damaged reproductive capacity due to the loss of breeding pigs, and the financial losses from supply disruptions caused by the abandonment of farming and other factors (for example, underreporting). We also evaluate the economic losses to all sectors in China using the input–output model. Furthermore, the loss in consumer surplus caused by the outbreaks of ASF and the costs incurred by state and local governments in relation to the prevention and control of the epidemic are assessed and discussed. Finally, we provide a scenario analysis based on different assumptions regarding the reduction in pig production and the increase in prices caused by ASF. Our findings can help Chinese policymakers to better understand the financial losses of the ASF epidemic and evaluate the effectiveness of related policies, and also provide a scientific decision-making reference for countries affected by animal diseases, to help them formulate tailored epidemic prevention and control measures, and livelihood and food safety policies.

Results

Official figures being understated

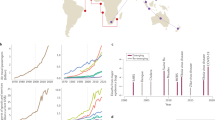

In August 2018, ASF was detected in Shenyang in Liaoning province, China, and then spread to all mainland provinces. As of July 2019, there were a total of 162 ASF outbreaks in all parts of China. Figure 1 shows the numbers of ASF outbreaks and pig deaths during the first year of the ASF pandemic. According to official data, by mid-2019, 13,355 pigs had died due to the ASF virus infection, and 1,204,281 pigs had been culled to halt the virus’s spread. The epidemic has caused considerable economic losses to the Chinese animal husbandry industry, and has even led to a sharp disruption in the livestock supply chain and meat consumption structure.

The numbers of ASF outbreaks and pig culling and deaths during the first year of the ASF pandemic in China are shown. The left axis shows the monthly number of ASF outbreaks and the right axis shows the monthly number of pigs died or culled due to the ASF outbreaks. The ASF epidemic reached its peak in September and October 2018.

According to the China Statistical Yearbook, for the period 2010–2018 the number of pigs slaughtered and the total pig herd in China were about 700 million and 450 million head per year, respectively. The officially released data on culling and deaths caused by the ASF accounts for less than 0.2% of the yearly number of slaughtered (healthy) pigs12. This figure is much smaller than some industry estimates (150–200 million)13, indicating that the official data may not reflect the true scale of the ASF outbreak. There are several reasons we believe the official figures may be underreported. First, in China, small and medium-sized farms (those with fewer than 500 head) account for more than 95% of the pig farming industry. It is a common practice on these small and medium-sized farms to feed untreated swill to pigs. Waste management and sanitary conditions are relatively poor, and little is invested in the prevention and control of infectious swine diseases. Therefore, once a pig disease begins to circulate, those small farms will often be almost totally destroyed. It is difficult to obtain a complete and accurate picture of slaughter and on-farm death figures on small and medium-sized farms. Second, due to the lack of efficient treatments and vaccines to counter the ASF virus, and the insufficient funds and compensation available to farmers to help them to resume pig breeding, most of them have decided to quit farming pigs (that is, abandonment), at least in the short to medium term, to avoid further financial losses. This impact in terms of future shortages in the pig supply market will not be captured by the culling and death data.

It is worth noting that, from 2015, the Chinese government started to introduce non-livestock production regions and pig-reallocation policies to prevent the pollution of major water sources and odour caused by agricultural activity. The implementation of those policies has caused a decrease in the number of slaughtered pigs over time. Specifically, compared with 2014, in which 749.51 million pigs were slaughtered, the number of pigs slaughtered decreased by 25.36 million in 2015, by 48.78 million in 2016, by 47.49 million in 2017 and by 55.69 million in 201814,15, suggesting that the policies have had a lasting impact on pork production. Therefore, the shrinking supply in the pig market since the outbreak of ASF has two main causes: the remaining effect of the ban on breeding of pigs, which we estimate to have resulted in 46 million fewer pigs being slaughtered over our sample period, and the ramifications of the ASF epidemic.

We estimate that 43.46 million pigs died either due to ASF virus infection, being culled to stamp out the virus or as a consequence of other ASF-related impacts during the first year of the ASF outbreaks, accounting for 6.3% of the total number of pigs slaughtered in 2018 (that is, 693.824 million). According to the China Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Statistics (2019), we assume that the average weight of a slaughtered pig is 120.76 kg and the average dressing percentage of pigs is 70%16. The total economic loss caused by the ASF outbreak is estimated to be about US$111.2 billion, amounting to 0.78% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019. The total economic loss consists of direct economic losses to the swine industry, indirect economic losses to all sectors of the economy, the decrease in consumer surplus and government losses (excluding costs for non-affected areas).

Direct economic losses

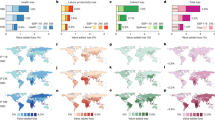

Across the Chinese provinces, the average direct financial loss due to mortality and culling was US$8.7 million per province, and almost half of the provinces suffered more than US$4.5 million in financial losses. The province of Liaoning was the most severely damaged by ASF, with a direct financial loss that amounted to US$55 million (Fig. 2). Moreover, based on official data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank17,18, the financial loss from decreased reproduction due to deaths from ASF and culling of breeding pigs is estimated to have been US$681 million. The financial loss caused by abandonment and other reasons is estimated to have been US$10 billion (Supplementary Table 1).

The levels of economic loss (in thousands of US dollars) across provinces in mainland China. The bright colours represent low levels of direct economic loss; the dark colours represent high levels of direct economic loss. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of provinces for which the direct economic loss is within the range. The box on the right-hand side represents the South Sea Islands of China.

Indirect economic losses

The total indirect economic losses to producers in all sectors of the Chinese economy (149 sectors) are estimated to have been US$14.5 billion. Across the different provinces in China, this varies from US$2.2 billion in Guangdong province to US$1.4 million in Qinghai province. The average indirect economic losses of producers per province were US$467.8 million and 18 provinces suffered losses of between US$100 and US$900 million (Fig. 3). The provinces with high economic losses for producers are mainly located in the eastern coastal, central and southern parts of China. These findings suggest that the ASF epidemic has not only directly hit the swine industry, but almost all economic sectors through its links, leading to considerable economic losses.

The levels of indirect economic loss (in thousands of US dollars) across provinces in mainland China. The losses are estimated through the input–output model. The bright colours represent low levels of indirect economic losses; the dark colours represent high levels of indirect economic loss. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of provinces for which the indirect economic loss is within the range. The box on the right-hand side represents the South Sea Islands of China.

Decrease in consumer surplus and government losses

The decrease in consumer surplus caused by the outbreaks of ASF is estimated to be US$84.9 billion. This is more than three times the total production losses (that is, US$25.9 billion), suggesting the economic losses have mainly come from the decrease in consumer surplus. Finally, the government losses associated with ASF are about US$364 million (see Supplementary Table 2 for an explanation of the calculation of government costs). Relative to the other economic losses, the government losses are very low (Supplementary Table 3). This suggests that increases in expenditure and investment in the prevention and control of ASF may help to reduce the economic losses for producers and consumers.

Scenario analysis

To explore a broad range of future uncertainties and corresponding realities, and to shed light on the economic losses likely to be associated with future ASF outbreaks, we conduct a series of sensitivity analyses based on different scenarios. First, taking the estimated case of a 6.3% reduction in China’s pig production as a reference scenario (S0), five other scenarios are analysed, in which the reduction in pig production is scaled down by 20%, or scaled up by 20%, 40%, 60% and 80% (S−20, S20, S40, S60 and S80). We also explore five scenarios of pork prices where pig carcasse and pork prices either remained constant, fell by 20% or increased by 20%, 40% or 60% and 80% (SP−20, SP20, SP40, SP60 and SP80). We apply the same method as before to estimate the total economic loss and its components for each scenario. The estimated results are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

From the best-case (SP−20) to the worst-case (S80) ASF scenario, the direct financial losses to the swine industry range from US$9.1 billion to US$20.6 billion, and the total economic losses range from US$89.5 billion to US$196.2 billion, accounting for between 0.6% and 1.4% of China’s GDP in 2019. China has the largest hog herd in the world and accounts for roughly 45% of global pork production19. A considerable reduction in the pig population would result in a serious shortage of pork supply, an increase in the demand for and prices of substitute commodities and feed ingredients, and even a change in the diet culture in China, and the impairment of calorie availability and nutrition intake in some underdeveloped areas in the world13.

The worst scenarios (S40, S60 and S80) would trigger a loss of more than 1% of GDP, which would exert a substantial socioeconomic impact on China. Thus, the government should prepare policies to avoid these worst-case situations by implementing strong measures to effectively prevent and control the spread of the epidemic.

The ASF outbreaks are still ongoing in China and creating considerable uncertainty about pork prices, a situation that directly affects pork production and consumer welfare. Our sensitivity analysis on pork prices shows that from the best-case (SP−20) to the worst-case (SP80) ASF scenario, the total economic losses range from US$60.6 billion to US$296.9 billion, accounting for between 0.42% and 2.07% of China’s GDP in 2019. The price changes mainly impact the consumer surplus and the worst case could result in a decrease of US$211.18 billion in consumer surplus, 2.9-fold higher than the reference point.

Discussion

The impact of ASF on people’s livelihoods and health and food security is potentially disastrous. In 2019, during several important national holidays, the Chinese government repeatedly released 10,000–30,000 t of pork from state reserves to secure the meat supply. However, relative to the estimated reduction in pork supply due to ASF (3.67 Mt), these released frozen pork reserves represent a negligible amount. A reasonable estimate of the animal-sourced food reserve is essential to improve food safety and consumer welfare, and mitigate disease risks from livestock. In addition, to prevent the introduction of the ASF virus from and its transfer to other countries, strict compliance with regulations on the export and import of pork is important. Moreover, people’s meat-consumption attitudes and behaviours have undergone changes since the outbreak of ASF. Some people have begun avoiding eating pork because of a lack of understanding of the transmission of ASF virus, which does not pose a hazard to humans. Thus, the government has a responsibility to educate the public and help people to face and understand animal diseases.

A lack of crucial data is one of the main challenges we faced in this research. Missing data can reduce the statistical power of a study and cause biased estimates, leading to invalid conclusions. Thus, this study uses a substitution indicator approach for handling incomplete/missing data. There is a large gap between the officially stated and actual data on the number of pigs that have died or been culled because of ASF. Estimates should be based on data and information that adequately reflect the true picture. We believe the data gap mainly comes from the following sources: an impaired reproductive capacity caused by the reduction in the number of breeding pigs due to deaths and culls; a substantial drop in the hog herd supply caused by farmers stopping breeding pigs; and underreporting in official data collection. The substitution indicator estimation considers and integrates information closely related to the number of slaughtered pigs. Pig feed production is closely related to the number of pigs. Therefore, we use the information on swine feed production reduction and average feed intake for a pig to construct a substitution indicator to proxy for the actual reduction in the number of pigs. This substitution indicator estimation approach will address the incomplete/missing data problem and should prove very useful for other similar economic evaluations.

Methods

Economic loss evaluation system

In this study the economic losses caused by ASF are evaluated by considering four aspects: the direct economic losses to the swine industry, the indirect economic losses to all sectors of China’s economy, the decrease in consumer surplus and government losses. A schematic diagram of the proposed evaluation system is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

The swine industry’s direct economic loss includes three components: the economic losses from the culling and removal of infected carcasses, the economic losses due to impaired reproductive capacity caused by the reduced number of breeders, and the economic losses due to the shrinking of the pig supply market. A deterministic calculation and a substitution indicator are applied to estimate the above losses. The industrial structure and food consumption vary across provinces in China. To consider the possible impact of such geographic differences and achieve a more accurate estimation, we estimate each type of economic loss at the province level. These estimations can also provide a scientific decision-making reference for each province to use to make tailored control and prevention policies.

The indirect economic losses to all sectors of the economy are estimated based on complete consumption coefficients obtained from the 2017 input–output table published by the National Bureau of Statistics of China20. A complete consumption coefficient refers to the amounts of products or services of each sector that need to be consumed directly and indirectly (that is, completely consumed) for each unit of the final product provided by a specific sector to be produced. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the indirect influence coefficients of the swine industry on each industry.

We then estimate the decrease in consumer surplus, which refers to the change of consumer welfare under the pork market’s partial equilibrium before and after the outbreaks of ASF. Finally, we assess the government losses, which refer to the government’s emergency expenditure on controlling and extinguishing the epidemic, including investments and expenses related to culling and disposal, culling compensation, disinfection, movement restrictions in epidemic-affected areas, protective materials, emergency command and supervision, investigation and monitoring, and propaganda and training.

Economic loss from removal of swine

In this study the direct economic loss associated with dead and culled pigs is estimated by the following equation:

where L0 represents the direct economic losses from the death and culling of pigs caused by ASF, nd and nk (head) are the number of dead pigs due to ASF directly and the number of pigs culled in efforts to prevent the virus’s spread, respectively, w0 is the average weight of the slaughtered pigs (kg head−1) and v0 (US$ kg−1) is the market price of pig carcasses in each province when the ASF outbreaks occurred.

Damaged reproductive capacity

The economic losses caused by the reduction in the number of breeding pigs are denoted by L1 and estimated by the following equation:

where Rb is the ratio of the number of breeding pigs to the total number of fattening pigs at the end of each year (pig inventory) (Supplementary Table 4), nb (offspring per head) is the average annual reproductive capacity of each breeding pig and v1 (US$ kg−1) is the average market price of pig carcasse during January 2019 and July 2019 in each province (see Supplementary Table 5).

Abandonment of farming and other factors

Due to the lack of the required official data on abandonment of pig farming, this study uses an innovative approach for handling incomplete/missing data. As discussed above, the actual reduction in the number of pigs due to ASF is unclear. Therefore, we use the difference between swine feed production before and that after the ASF outbreak (that is, the yearly feed production reduction) divided by the average yearly feed intake per pig as the substitution indicator for the total reduction in the number of slaughtered pigs in the estimation interval. The related calculations are as follows:

where the reduction in the number of slaughtered pigs due to the policy of prohibiting pig breeding over the estimation period is estimated at 46 million head, and the reduction due to ASF is equal to the official death and culling data plus the reduction in reproduction capability due to the reduction in the number of breeding pigs plus the shrinking of the future pig supply market due to the stopping of farming and other factors. NLPRs are non-livestock production regions.

Indirect economic loss to all sectors of the economy

Input–output economic models are widely used to assess the impact of shocks such as the COVID-19 outbreak, disasters and contagious diseases21,22,23. Based on input–ouput tables, the input–ouput model establishes corresponding linear equations to describe the chain relationship between production and consumption among economic sectors. Although the input–ouput model can effectively evaluate the impact of a disruption on one sector of an economy, and the associated loss assessment for other sectors24,25, one of the model’s weaknesses is that it does not consider the impact of changes in prices. The correlation of industries in the input–ouput tables of a static input–ouput model is expressed as follows: AX + Y = X, that is, \(\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{i,j = 1}^n {a_{ij}X_j} + Y_j = X_i\), where i represents the input sector, j represents the output sector, aij is the direct consumption coefficient, which refers to the quantity of products that need to be directly consumed in sector i to produce products per unit of sector j, A is the direct consumption coefficient matrix, Xj represents the total output from sector j, Xi represents the total output of sector i, Yi is the demand of sector i, and X = (I − A)−1Y is obtained, where I is the identity matrix. The indirect input loss is represented by the reduction of intermediate input as ΔX − ΔY. Since \({\Delta}X - {\Delta}Y = \left[ {\left( {I - A} \right)^{ - 1} - I} \right]{\Delta}Y\), B is a complete coefficient consumption matrix, such that B = (I − A)−1 − I (refs. 26,27).

Assume sector i suffers the loss ΔYi:

Thus, the total production loss of sector i is given by \({\Delta}X_i = b_{ii}{\Delta}Y_i + {\Delta}Y_i\) and the loss of the other sectors is given by \({\Delta}X_n = b_{ni}{\Delta}Y_i,(n \ne i)\).

Change in consumer surplus

In this study we use a partial equilibrium model to evaluate the change in consumer surplus13. Under the partial equilibrium conditions of a perfectly competitive market, the demand curve and the supply curve jointly determine the local equilibrium point of the market. The partial equilibrium of the pork market is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. For simplification purposes, we assume that the supply (S) and the demand (D) curves are straight lines. It is worth noting here that the curves are ideally estimated using supply and demand elasticities, which would give the actual slope and overall shape of the curves. However, our simplified linear approximation can still give a useful sense of the potential impact on the consumers and provide a good estimation.

At the beginning of the period, the intersection of the supply curve S1 and the demand curve D determines the equilibrium E of the pork market, where the equilibrium price and quantity are P1 and Q1, respectively. The total consumer surplus is the sum of areas A and B. Since 2015, the Chinese government has gradually implemented a ban on pig breeding in designated regions to address environmental pollution problems. Combined with the outbreak of ASF, this ban caused a sharp drop in pork supply during our estimation period. Thus, assuming other conditions remain unchanged, at the end of the period, the supply curve S1 shifts to the left, remaining parallel, to become the new supply curve S2, and the demand curve D remains unchanged, forming an equilibrium F. The equilibrium price and quantity are P2 and Q2, respectively, and consumer surplus is adjusted to area A. Therefore, the change of consumer surplus jointly caused by ASF and the ban on pig breeding policy in our evaluation period is area B. The equilibrium points E and F could determine the demand curve D. In this study, we only focus on evaluating the economic impact of ASF. So after removing the effect of the ban policy, we get the supply curve S3 and the new equilibrium H that would occur under the impact of ASF alone, with equilibrium price and quantity P3 and Q3, respectively. Therefore, the change of consumer surplus caused by the ASF epidemic is defined as:

where P1 is the average price of pork at the beginning of the period, P3 is the average price of pork under the impact of the ASF epidemic alone (see Supplementary Table 6), Q1 is the average pork consumption at the beginning of the period and Q3 is the average pork consumption when reduced by the ASF epidemic.

Government losses

The direct government losses (costs) associated with the ASF are estimated by the following equation:

where Lg represents the direct government losses associated with the death and culling of pigs caused by ASF; cg is the average government expenditure per dead or culled pig, calculated by the sum of average costs of culling and disposal, cleaning and disinfection, movement restrictions for ASF-affected areas, protective materials, emergency command and supervision, investigation and monitoring, and propaganda and training; and cc is the average compensation for culled pigs. Information on these average costs is collected from a survey conducted by the China Animal Health and Epidemiology Center in the ASF-affected areas in 2019 (internal database). Based on the government official data, the total dead and culled pigs caused by ASF from August 2018 to July 2019 are 13,355 (nd) and 1,204,281(nk), respectively. See Supplementary Table 2 for details.

Statistics and reproducibility

The results of this research can be reproduced and verified based on the information and data provided in the Supplementary Information and the Supplementary Data files. In this research, no statistical method was used to predetermine sample size and no data were excluded from the analyses.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings and of this study are available in the Supplementary Information and Source Data files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Moennig, V. Introduction to classical swine fever: virus, disease and control policy. Vet. Microbiol. 73, 93–102 (2000).

Costard, S. et al. African swine fever: how can global spread be prevented? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 2683–2696 (2009).

O’Neill, X. et al. Modelling the transmission and persistence of African swine fever in wild boar in contrasting European scenarios. Sci. Rep. 10, 5895 (2020).

Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2018 National Economic and Social Development (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2020).

Rock, D. L. Challenges for African swine fever vaccine development—“… perhaps the end of the beginning”. Vet. Microbiol. 206, 52–58 (2017).

Schulz, K. et al. Epidemiological evaluation of Latvian control measures for African swine fever in wild boar on the basis of surveillance data. Sci. Rep. 9, 4189 (2019).

Saatkamp, H. W., Berentsen, P. B. M. & Horst, H. S. Economic aspects of the control of classical swine fever outbreaks in the European Union. Vet. Microbiol. 73, 221–237 (2000).

Schulz, K. et al. Surveillance strategies for classical swine fever in wild boar—a comprehensive evaluation study to ensure powerful surveillance. Sci. Rep. 7, 43871 (2017).

Chiang, L. & Sun, J. Impacts of African Swine Fever on China’s Feed Industry and Soy Demand (Rabobank, 2019).

Muñoz-Moreno, R. et al. Analysis of HDAC6 and BAG3-aggresome pathways in African swine fever viral factory formation. Viruses 7, 1823–1831 (2015).

Porphyre, T. et al. Vulnerability of the British swine industry to classical swine fever. Sci. Rep. 7, 42992 (2017).

African Swine Fever Outbreak Information (Ministry of Agriculture of the PRC, 2020); http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/fzzwfk/yqxx/index_24.htm

Mason-D’Croz, D. et al. Modelling the global economic consequences of a major African swine fever outbreak in China. Nat. Food. 1, 221–228 (2020).

Data of the Number of Pigs Slaughtered in 2014-2018 from China Statistical Yearbook (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2019); http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/

Bai, Z. et al. China’s pig relocation in balance. Nat. Sustain. 2, 888 (2019).

Schweihofer. J. P. Carcass Dressing Percentage and Cooler Shrink (Michigan State University Extension, 2011); https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/carcass_dressing_percentage_and_cooler_shrink

The Number of Pigs Slaughtered and the Herd Size of Pigs in China (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2020); http://zdscxx.moa.gov.cn:8080/nyb/pc/search.jsp

African Swine Fever and its Loss Assessment in China and its Neighboring Countries (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, 2020).

FAOSTAT: Food and Agriculture Commodities Production (FAO, 2019).

China’s Regional Input–Output Table (Department of National Accounts, National Bureau of Statistics, 2017); https://data.stats.gov.cn/ifnormal.htm?u=/files/html/quickSearch/trcc/trcc01.html&h=740&from=groupmessage&isappinstalled=0

Duan, H., Wang, S. & Yang, C. Coronavirus: limit short-term economic damage. Nature 578, 515 (2020).

Galbusera, L. & Giannopoulos, G. On input–output economic models in disaster impact assessment. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 30, 186–198 (2018).

Santos, J. R., May, L. & Haimar, A. E. Risk-based input–output analysis of influenza epidemic consequences on interdependent workforce sectors. Risk Anal. 33, 1620–1635 (2013).

Crowther, K. G., Haimes, Y. Y. & Taub, G. Systemic valuation of strategic preparedness through the application of the inoperability input–output model with lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina. Risk Anal. 27, 1345–1364 (2007).

Tan, L. et al. Comprehensive economic loss assessment of disaster based on CGE model and IO model—a case study on Beijing “7.21 rainstorm”. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 39, 101246 (2019).

Leontief, W. Quantitative input and output relations in the economic system of the United States. Rev. Econ. Stat. 18, 105–125 (1936).

Miller, R. E. & Blair, P. D. Input–Output Analysis: Foundations and Extensions 2nd edn (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank H. P. Zhu for his valuable comments on the research ideas in the early stage of our research. Y.D. acknowledges financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; grant numbers 71873103 and 72071142). B.S. acknowledges financial support from the NSFC (grant numbers 71873103, 71731003 and 71603141) and the Innovation Capability Support Program of Shaanxi (number 2019KJXX-070).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. and B.S. conceptualized and designed the research. T.L. and Y.D. drafted the paper. T.L., M.Z., X.Z., B.W., Y.W., J.L. and X.W. acquired and analysed the data. All authors interpreted the data. Y.D., S.Y., M.Z. and B.S. substantively revised the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the final version and agreed to be personally accountable for their own contributions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Food thanks Yasha Feferholtz and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–6 and Figs. 1–3.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical Source Data

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical Source Data

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical Source Data

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

You, S., Liu, T., Zhang, M. et al. African swine fever outbreaks in China led to gross domestic product and economic losses. Nat Food 2, 802–808 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00362-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00362-1

This article is cited by

-

The diffusion metrics of African swine fever in wild boar

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

A global dataset for prevalence of Salmonella Gallinarum between 1945 and 2021

Scientific Data (2022)

-

Point and interval prediction of crude oil futures prices based on chaos theory and multiobjective slime mold algorithm

Annals of Operations Research (2022)

-

The $100-billion toll of a pig epidemic in China

Nature (2021)