Abstract

Access (the ease of reaching valued destinations) is underpinned by land use and transport infrastructure. The importance of access in transport, sustainability, and urban economics is increasingly recognized. In particular, access provides a universal unit of measurement to examine cities for the efficiency of transport and land-use systems. This paper examines the relationship between population-weighted access and metropolitan population in global metropolitan areas (cities) using 30-min cumulative access to jobs for 4 different modes of transport; 117 cities from 16 countries and 6 continents are included. Sprawling development with the intensive road network in American cities produces modest automobile access relative to their sizes, but American cities lag behind globally in transit and walking access; Australian and Canadian cities have lower automobile access, but better transit access than American cities; combining compact development with an intensive network produces the highest access in Chinese and European cities for their sizes. Hence density and mobility co-produce better access. This paper finds access to jobs increases with populations sublinearly, so doubling the metropolitan population results in less than double access to jobs. The relationship between population and access characterizes regions, countries, and cities, and significant similarities exist between cities from the same country.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cities exist to enable people to easily reach other people, goods, and services. This is achieved through transport networks, which move people across space faster, and land-use patterns, which distribute people, goods, and services across space. Access (or “accessibility”) is the ease of reaching those valued destinations, and thus is a critical measure of urban efficiency. Higher land use density and travel speeds correspond with greater access1. Urban population size has been associated with greater productivity and creativity, a centerpiece of the urban economies of agglomeration literature2,3. This paper measures how access varies with metropolitan population size, whether larger cities also enjoy increasing accessibility, which we expect will affect how well population produces economies of agglomeration.

To measure access across the globe, we use the cumulative number of job opportunities reachable under a predefined travel time threshold. Since jobs are places of interaction, that provide service either directly or indirectly to customers, jobs are a key indicator of “urban opportunities”4 serving both as employment opportunities, and as urban amenities.

The role of access in transport, sustainability, and urban economics is increasingly recognized. The positive correlation between access and land value originates from the trade-off between time (transport cost) and space (the price of land)5,6,7, and this positive correlation has been shown with various hedonic models in different contexts8,9,10. Access affects firm location choice11, development probability of vacant land12, commute mode choice13,14, and transport emissions15. The expansion and rapid growth of urban areas call for a meaningful measure of geographical connectivity, to which a measure of access to job opportunities can be a useful tool16.

Cities have been ranked and recognized by economic and demographic statistics that describe their sizes and productivity17,18,19,20. The efficiency of transport infrastructure and land use in linking people with opportunities is also a vital measure for cities21,22,23, and its significance is on par with economic and demographic measures. However, there has been no previous large-scale, multi-modal comparison of access to jobs for cities across the globe. Cities differ in the levels of transport infrastructure and development patterns. On the one hand, US cities prioritize mobility over density; the density of US cities are relatively low24 due to sprawling development patterns. Road length per vehicle is higher in the US than in Europe, Canada, and Oceania25. On the other hand, European cities are compact and have a denser road network than US, Canadian, and Oceania cities25. These differences among cities and global regions would have accessibility implications, that affect the quality of the transport system within each city. This paper examines the type of development pattern most conducive to accessibility, and whether mobility and density can co-exist for better accessibility.

Understanding global urbanization and transport development are needed26. The quantification of access using cumulative opportunities provides a universal unit of measurement for transport and land use, and the opportunity for defining cities by transport and land use with a uniform benchmark. Measuring accessibility sheds light on the basic structure of cities underpinning economic efficiency, and reveals where a city (i.e., metropolitan area) stands relative to its overall size and other attributes, and relative to other cities.

Access has been measured and compared domestically in the United States27, Australia28, Brazil29, Canada30, New Zealand31, and in European countries32 using the cumulative opportunities measure. One notable advantage of the cumulative opportunities measure is being in absolute and comparable units33, and having clarity of meaning, and being an easily understood and interpretable concept34. This paper uses a travel time threshold of 30 min that is consistent with many estimates of one-way travel time budgets to work, to measure access to jobs in all cities35,36,37,38,39.

This paper compares access globally and covers access by automobile, transit, walking, and cycling where data were available. We examine patterns in the relationship between access and populations, and whether cities cluster by their global region. This work also examines whether the disparity in access to jobs between modes of transport is linked with population size. Access to jobs data in this global comparison are collected by different researchers and organizations. The population provides a consistent measure of metropolitan area size that is comparable across global regions. This paper details the data collected from multiple agencies in the supplementary information, commenting on differences in data sources. Access measures for each model are tabulated and cities ranked by the total population in the supplementary information. The paper examines access in global cities across modes, across countries, and across cities.

Results

Comparison across countries: scaling city-level access with population

In order to compare accessibility across cities worldwide, we first compare the relationship between the population size and accessibility in different countries. Such comparison can help clarify the differences in the relationship, and in the returns to scale of metropolitan population size on accessibility between different countries, i.e., is the increase in access proportional to the increase in population in each country, and how different countries compare.

We use scaling functions to quantitatively measure the relationship between population and the level of access to jobs. The formulation of the scaling function is shown in the methods sections. The scaling coefficient (β1) signifies the returns to scale, where β1 > 1 means doubling the metropolitan population will more than double the level of access. We find the city-level access to jobs increases with population. Table 1 shows the model fit and coefficients.

Although the relationship between access and population, in general, is positive, with larger cities exhibiting higher accessibility by all modes than their smaller counterparts within the same counties (the β1 coefficients are positive), we generally see diminishing returns in access with respect to population (the coefficient is less than one), so we have sublinear scaling, meaning population rises faster than access. Notably, transit in Chinese cities is the only exception to the sublinear scaling: the increasing population in Chinese cities confers proportionally more accessible jobs.

Comparison across modes

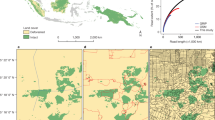

We compare city-level access to jobs by four modes of transport: automobile, transit, walking, and cycling. The population and access by different modes on a logarithm scale are plotted in Fig. 1 through Fig. 4; scaling functions are fitted as trend lines. Figures showing the accessibility by different modes of transport for each country is provided in the Supplementary Information. Cities above the trend lines are overperforming based on their mode and country category; cities beneath the trend lines are underperforming. Our comparison corroborates that differences in structure exist both within, and between, global regions. Although cities of the same global region tend to share similar trends in access, cities from different global regions can cluster on access attributes.

Walking access to jobs is shown in Fig. 1. Walking is part of every other mode of transport. The walking access alone represents the spatial distribution of population relative to urban opportunities. Urban density, the proximity between residential and employment centers40, and mixed land use increase walking access.

For any given population, Chinese and European cities have markedly higher walking access to jobs than cities in other countries. American cities, with their lower densities and auto-orientation, as well as the functional separation between residential and employment districts, have the lowest walking access to jobs globally. Among American cities, New York and San Francisco-Oakland (excluding San Jose) are more similar to European cities than to other American cities. In Oceania, Wellington also clusters amongst European cities with significant walking access to jobs, and Sydney comes close to European access levels.

Cycling access is shown in Fig. 2. Cycling access in major cities tends to be below automobile, but higher than transit. Chinese and European cities generally have greater cycling access than the US cities with similar population sizes. Cycling access in Oceania cities is comparable to the best American and Brazilian cities, but lower than Chinese and European cities.

Cycling provides better access to jobs than transit in every city where access data of the two modes are available. Cycling has no waiting or transfers time penalties, and cycling routes to and from destinations are less circuitous than transit. Cycling provides better access than automobiles in the city of Shanghai, where congestion reduces access by automobile.

Transit access is plotted against the population in Fig. 3. Transit service provision is linked to patronage in a positive feedback system41, which affects transit performance, so more populous cities with a greater base for transit patronage tend to have better transit quality of service, with higher frequency, shorter access distances, and more direct service, resulting in higher access to jobs42.

Chinese and European cities have higher transit accessibility than the others. London and Paris have a longer history than North American cities and were well developed before the advent of the automobile. It is expected that these European cities would better support transit and walking. Australian and Canadian cities are similar in terms of transit access, with the exception of Quebec City, which, despite its age, more resembles American cities. Brazil’s largest metropolises, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro have much lower accessibility levels than what would be expected for their population. This is in part because these two cities have large territories with low population densities coupled with a high concentration of jobs in the city center, and both cities have relatively poor transport conditions with some of the highest average commute times among global cities43.

The majority of American cities lag behind in transit access for their population size. New York and San Francisco-Oakland are exceptions for the American cities, with high transit access relative to size. Metropolitan Washington, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Seattle bear more resemblance to Australian and Canadian cities than to other American cities, although transit access for these cities is still lower than their Australian and Canadian counterparts. The two African cities, Douala and Nairobi both have better walking and transit access than average American cities.

Automobile access is plotted in Fig. 4. Large cities tend to have well-developed road networks and have employment opportunities proportional to the population sizes, which, generally translates to greater automobile access. Conversely, heavy traffic flows can cause delays in large cities, especially during peak hours when automobile travel time data for this study are measured.

Both globally and within each nation, automobile access increases with population. Chinese and European cities follow a distinct trend from other global cities and have the highest automobile access for each population level. American cities have greater automobile access than Australian and Canadian cities at each level of population. Historically the United States has placed heavy emphasis on auto-mobility, and the Interstate highway system created by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 195644 greatly facilitates movement by automobile both within and between metropolises. New York has high automobile access, but its level did not grow out of proportion to make New York an outlier; New York is an outlier among US cities for high walking and transit access. Oceania and Canadian cities are comparable to American cities that are in the lower quantile of automobile access; Perth more resembles mid-tier American cities at its size.

Comparison across cities: access with populations

Across cities, we find population correlates with access to job opportunities. People in more populous cities generally have better accessibility. Population reflects the need for transport. On the one hand, it is hypothesized that larger metropolitan areas enjoy economies of agglomeration and tend to have better public transport systems and higher residential and employment densities, thus better access. On the other hand, congestion in large cities reduces access, and differences in urban networks and spatial configuration can result in varying levels of access for cities with similar sizes. Similarly, as the population increases, urban densities rise slower than the population, as some of the additional growth expands urban territory, and thus distances required45. In the Supplementary Information, we tabulate global cities by the access of different transport modes (where data were available).

The correlation between population and accessibility of different modes is strongest with the automobile (0.69), followed by cycling (0.55), walking (0.48), and transit (0.44). An automobile can generally reach more territory than other modes within a 30-min threshold, so the automobile accessibility relates more strongly with the metropolitan population than other modes. The weaker correlation for the transit mode is largely due to transit being the most susceptible mode to variations in service provision, and urban land use. Small cities with good transit infrastructure can provide similar levels of access to jobs within 30 min as many large cities (which may have more jobs available for longer time thresholds, which are less valuable to residents than nearer jobs). Examples of such small but compact cities with good transit services include most European cities, and Wellington and Christchurch in New Zealand, which have relatively good transit accessibility for their sizes. Large and densely populated metropolitan areas such as New York, London, and Paris have good transit accessibility.

Modal comparison: transit as a benchmark

We explicitly examine the disparity in access provided by different modes of transport from different cities, using transit as the benchmark. The existence and extent of such disparity vary by city, and by the country of the cities46. The difference in access by different modes is compared using the ratio of cumulative access so that the difference between modes is scalable. Since the access data from each city is collected by the same source and over the identical geographical extent, the ratio of access by mode provides a reliable gauge for comparing the within-city modal difference. Figure 5 shows the ratio of 30-min access to jobs by automobile and by cycling, relative to the transit mode.

The automobile provides better access than transit in all cities we compared, except in Shanghai, China, where automobile reaches about 90% of the jobs reachable by transit at 30 min. The disparity between transit and automobile access is greatest in American cities; Oceania and Canadian cities have more comparable levels of access between the two modes, although the gap remains significant. Among the Oceania cities, Perth and Wellington are the two extremes (outliers) for respectively having the largest and smallest gaps between transit and automobile access to jobs.

Transit and automobile often have the highest commute mode share in major cities. Income47 and physical ability affect mode choice, so the relative level of access to jobs provided by automobile and transit has equity implications48. The ratio of the automobile to transit access correlates weakly with population (R = 0.10), so larger populations reduce the gap between transit and automobile, but generally do not guard against inequitable transit access to jobs. US cities with better transit access tend also to have lower auto to transit access ratio; examples include New York, San Francisco-Oakland, Washington, and Boston.

The automobile provides better access than transit in almost all cities we compared. The disparity between transit and automobile access is greatest in American cities Fig. 5; Australian and Canadian cities have more comparable levels of access between the two modes. The ratio of the automobile to transit access does not seem to be affected by the population.

All cities we examined have cycling access higher than that of transit. Oceania and European cities have stable ratios of cycling to transit access, where cycling can reach about twice as many jobs as transit. The gap between cycling and transit access to jobs is larger in the US and Chinese cities. The ratio of cycling to transit accessibility has a weak correlation with populations (R = 0.17), so the gaps between transit and cycling are smaller with larger populations.

Discussion

This research conducts a systematic, multi-modal, international comparison of access to jobs, which is the core variable connecting transport networks and land use, and the central factor in characterizing cities and explaining why cities exist49. This paper compares the performance of the transport and land-use system across cities.

One notable finding of this paper is the national difference in the relationship between access and population. While outliers exist, there are remarkable similarities for cities in the same global region. We find mobility and density can co-exist and collectively co-produce greater access to jobs for a metropolitan area. Sprawling development accompanied by an intensive road network, as is common in American cities, results in modest automobile access, but low access for transit and active modes of transport. Oceania and Canadian cities, with US-style land, uses but without US-level freeway networks have relatively low automobile access and are generally situated between American and European cities in transit and walking. This is consistent with previous findings23. Chinese and European cities are compact, and well supported by road networks, resulting in the highest accessibility in all modes of transport.

While it is unsurprising that this paper finds city-level access increases with population, the relationship is neither linear nor constant across countries. Access does not increase proportionally with a population (for all modes in all countries where data are available, except transit in China), and presents diminishing returns to scale, so the doubling of city population will likely less than double access to jobs.

More populous cities present more available urban opportunities, usually at higher densities, with higher levels of traffic congestion and better public transport infrastructure. When appropriately matched with transport infrastructure, compact urban development generally improves access to jobs, despite increased congestion. In terms of the disparity between modes of transport, we find larger cities tend to narrow the gap between transit and automobile access to jobs. The disparity between transit and automobile is most significant in the US, mostly as a result of sprawling development, which increases automobile speeds and makes transit service more difficult.

Two major caveats are identified: the demarcation of city boundaries, and the jobs and population data source. The modifiable areal unit problem is present in defining the city boundary for analysis, for example, excluding lower-density outlying (exurban) areas likely inflates the access measure. Although there is no consistent standard for defining city boundaries across nations, the geographical area was chosen for measuring access generally reflects what would be considered the built-up, urbanized area in each city that envelops commute ties to the urban core. This city boundary issue is further alleviated by using the population-weighted access measure, where the population data were available. The second caveat involves the census data on jobs and population numbers collected (or not) by governments of different nations, that vary in accuracy and coverage. We believe that while more consistent standardization of city boundary measurement and employment definition would affect specific numbers, they would not substantially change the general findings and conclusions from this study. By definition in some sense, “informal economy” jobs are excluded in all countries (which underestimates access in some metropolitan areas much more than others), however, the magnitude of this is unclear by its very nature.

This work provides a cross-sectional comparison of cities, focusing on how cities of similar scales compare, in terms of the coupling between transport infrastructure and land use, measured by access. Future research can link access with other city-level characteristics, including income, GDP per capita, transport emissions, and commute duration, to shed light on the interplay between these elements. In the future, it will also be possible to explore time-series data on access across the globe, to observe the longitudinal trend in the co-evolution of access with other urban elements.

Methods

Method for measuring accessibility

Access is calculated as the cumulative number of jobs reachable under a 30-min travel time threshold. Equation (1) specifies the cumulative access measure, for a location of interest. The concept of cumulative opportunities can be conceived graphically as the geographical area covered within a travel time threshold, and the number of opportunities contained in that area.

Selection of travel time threshold affects the access measure50,51; although distance decay functions52 (time-weighted cumulative opportunities53) can be used to avoid the choice of thresholds, the difference in data sources and variations across geographies, as well as different preferences for travel between people in different cities, prevent the use of a consistent decay function. We use a 30-minute threshold without distance decay (Eq. (2)) for consistent comparison across modes.

where, Ai,m is access measure for zone i, by mode m; Oj number of jobs at zone j; f(Cij,m)is the travel time between zone i and j for mode m; t is the travel time threshold = 30 min.

Access measures for individual zones are aggregated to produce city-level averages. Person-weighted city averages are used where the population data were available, and the population of each subdivision is used as a weight. For the US, Australian, Chinese, and Polish cities, the working population is used as a weight; the total population is used as a weight for Brazilian, Canadian cities, Paris, and London. City-level access of African and Dutch cities are arithmetic averages of subdivisions and not weighted by population, and are thus expected to be lower than population-weighted measures for the same area. Equation (3) shows the formulation of population-weighted city-level access. This population-based weighting scheme reflects average access as experienced by the entire population.

where, \({A}_{I,m}^{\,}\) is the city-level access for mode m in the city I; pj is the population within zone j; and J is the number of zones within the city.

Accessibility data

Accessibility to jobs in each city is calculated based on the subdivision of the city into zones, the travel time between zones, and the number of jobs within each zone. Traffic54 and transit schedules can cause temporal variations in access55,56, so the level of access differs by hours of the day. Automobile accessibility is based on historical traffic data, and includes the effects of congestion; recurrent congestion is included for transit through the digitized transit schedule data; walking and cycling does not consider congestion and use all links where walking and cycling are legal, not only where they are pleasant. We measure access based on the morning peak travel time. A detailed description of data sources is provided in the Supplementary Information.

Pedestrians encounter both signalized intersections and non-signalized street crossings that add additional travel time, which is partially but incompletely accounted for by adjusting pedestrian walking speed, so walking access tends to be overestimated. Cycling access is calculated using all roads, although cyclists selectively use roads depending on vehicular speeds and levels of traffic for safety reasons, so actual access by cycling tends to be lower than estimates using all roads57,58. Digitized transit schedule information in general transit feed specification format (and a similar system in China) is used for calculating transit access. Transit travel time estimates cover transit station access, egress, waiting, and transfer time, and assumes perfect schedule adherence (on the theory that schedules have been calibrated to improve reported “on-time performance”, but perfect adherence may result in overestimation compared with actual access). The automobile travel time includes the effect of congestion, but not searching for parking.

Scaling access to population

To quantitatively measure the proportionality between population and the level of access to jobs, we group cities by country and fit scaling models59 (Eq. (4)) to cities of the same countries. The scaling coefficient (β1) signifies the returns to scale.

where, β0,β1 is the coefficients of the scaling model.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed during this study are described in the following data record: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1347686760. The access data are openly available as part of the figshare metadata record in the file “AllCities.csv”. A list of all cities included in the study, along with the sources of the data used for each city, is available in the file “SI for Urban Access Across the Globe—An International Comparison of Different Transport Modes.pdf”. Both of these files are also available in PDF format via the Supplementary Information of this article.

Change history

11 June 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-021-00035-9

References

Levine, J., Grengs, J., Shen, Q. & Shen, Q. Does accessibility require density or speed? A comparison of fast versus close in getting where you want to go in US metropolitan regions. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 78, 157–172 (2012).

Graham, D. J. Agglomeration, productivity and transport investment. J. Transp. Econ. Policy 41, 317–343 (2007).

Glaeser, E. L. et al. Cities, Agglomeration, and Spatial Equilibrium (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Merlin, L. A. A portrait of accessibility change for four US metropolitan areas. J. Transp. Land Use 10, 309–336 (2017).

Smith, A. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. MetaLibri Digital Library 2 (1776).

Alonso, W. Location and Land Use (Harvard University Press, 1964).

Vickerman, R. et al. Transit investment and economic development. Res. Transp. Econ 23, 107–115 (2008).

Osland, L. & Pryce, G. Housing prices and multiple employment nodes: is the relationship nonmonotonic? Hous. Stud. 27, 1182–1208 (2012).

Ahlfeldt, G. If Alonso was right: modeling accessibility and explaining the residential land gradient. J. Reg. Sci. 51, 318–338 (2011).

Mayor, K., Lyons, S., Duffy, D. & Tol, R. S. A hedonic analysis of the value of rail transport in the Greater Dublin area. J. Transp. Econ. Policy 46, 239–261 (2012).

Ingram, D. R. The concept of accessibility: a search for an operational form. Reg. Stud. 5, 101–107 (1971).

Hansen, W., G. How accessibility shapes land use. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 25, 73–76 (1959).

Owen, A. & Levinson, D. M. Modeling the commute mode share of transit using continuous accessibility to jobs. Transp. Res. A 74, 110–122 (2015).

Wu, H., Levinson, D. & Owen, A. Commute mode share and access to jobs across US metropolitan areas. Env. Plan. B. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808319887394 (2019).

Stokes, E. C. & Seto, K. C. Tradeoffs in environmental and equity gains from job accessibility. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, E9773–E9781 (2018).

Biazzo, I., Monechi, B. & Loreto, V. General scores for accessibility and inequality measures in urban areas. R. Soc. Open Sci. 6, 190979 (2019).

Levinson, D. Network structure and city size. PloS ONE 7, e29721 (2012).

Arcaute, E. et al. Constructing cities, deconstructing scaling laws. J. R. Soc. Interface 12, 20140745 (2015).

M, B. The size, scale, and shape of cities. Science 319, 769–771 (2008).

Bettencourt, L. M., Lobo, J., Helbing, D., Kühnert, C. & West, G. B. Growth, innovation, scaling, and the pace of life in cities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7301–7306 (2007).

Derrible, S. & Kennedy, C. Characterizing metro networks: state, form, and structure. Transportation 37, 275–297 (2010).

Roth, C., Kang, S. M., Batty, M. & Barthelemy, M. A long-time limit for world subway networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 2540–2550 (2012).

Newman, P. G. & Kenworthy, J. R Cities and Automobile Dependence: An International Sourcebook (1989).

Marshall, W. E. Understanding international road safety disparities: why is Australia so much safer than the United States? Accid. Anal. Prev. 111, 251–265 (2018).

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Environment at a Glance: OECD Indicators. (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2015).

Angel, S. et al. Atlas of Urban Expansion (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, MA, 2012).

Accessibility Observatory, Access Across America. University of Minnesota, http://access.umn.edu/research/america/ (2017).

Wu, H. & Levinson, D. Access Across Australia. TransportLab, http://hdl.handle.net/2123/20509 (2019).

Pereira, R., Braga, C. K., Serra, B. & Nadalin, V. Desigualdades socioespaciais de acesso a oportunidades nas cidades brasileiras, 2019. Texto para Discussão IPEA 2535, http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/9586 (2019).

Allen, J. & Farber, S. A measure of competitive access to destinations for comparing across multiple study regions. Geogr. Analysis 52, 69–86 (2020).

Wu, H. & Levinson, D. Access Across New Zealand. TransportLab. https://hdl.handle.net/2123/21853 (2020).

Dimitrios, P. & Nicolas, W. Benchmarking accessibility in cities: measuring the impact of proximity and transport performance. Int. Transp. Forum Policy Pap. 68, 8–374 (2019).

Batty, M. Accessibility: in Search of a Unified Theory (2009).

O’Sullivan, D., Morrison, A. & Shearer, J. Using desktop GIS for the investigation of accessibility by public transport: an isochrone approach. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 14, 85–104 (2000).

Levinson, D. & Kumar, A. The rational locator: why travel times have remained stable. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 60, 319–332 (1994).

Levinson, D. & Wu, Y. The rational locator reexamined: are travel times still stable? Transportation 32, 187–202 (2005).

Mokhtarian, P. L. & Chen, C. TTB or not TTB, that is the question: a review and analysis of the empirical literature on travel time (and money) budgets. Transp. Res. A 38, 643–675 (2004).

Marchetti, C. Anthropological invariants in travel behavior. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 47, 75–88 (1994).

Zahavi, Y. & Ryan, J. The stability of travel components over time. Traffic Engineering and Control (1978).

Sarkar, S., Wu, H. & Levinson, D. Measuring polycentricity via network flows, spatial interaction and percolation. Urb. Stud. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019832517 (2019).

Mohring, H. Optimization and scale economies in urban bus transportation. Am. Econ. Rev. 62, 591–604 (1972).

Verbich, D., Badami, M. G. & El-Geneidy, A. M. Bang for the buck: toward a rapid assessment of urban public transit from multiple perspectives in North America. Transp. Policy 55, 51–61 (2017).

Pereira, R. & Schwanen, T. Commute Time in Brazil (1992-2009): differences between metropolitan areas, by income levels and gender. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (Ipea). http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/964 (2013).

Weingroff, R. F. Federal-aid highway act of 1956: creating the Interstate system. Public Roads 60 (1996).

Marshall, J. D. Urban land area and population growth: a new scaling relationship for metropolitan expansion. Urb. Stud. 44, 1889–1904 (2007).

Niedzielski, M. & Kucharski, R. Impact of commuting, time budgets, and activity durations on modal disparity in accessibility to supermarkets. Transp. Res. D 75, 106–120 (2019).

Jara-Díaz, S. R. & Videla, J. Detection of income effect in mode choice: theory and application. Transp. Res. B 23, 393–400 (1989).

El-Geneidy, A. et al. The cost of equity: assessing transit accessibility and social disparity using total travel cost. Transp. Res. A 91, 302–316 (2016).

Levinson, D. & Wu, H. Towards a general theory of access. J. Transp. Land Use 13, 129–158 (2020).

Xi, Y., Miller, E. & Saxe, S. Exploring the impact of different cut-off times on isochrone measurements of accessibility. Transp. Res. Rec. 2672, 113–124 (2018).

Pereira, R. H. Future accessibility impacts of transport policy scenarios: equity and sensitivity to travel time thresholds for Bus Rapid Transit expansion in Rio de Janeiro. J. Transp. Geogr. 74, 321–332 (2019).

Paez, A. et al. Accessibility to health care facilities in Montreal Island: an application of relative accessibility indicators from the perspective of senior and non-senior residents. Int. J. Health Geogr. 9, 52 (2010).

Wu, H. & Levinson, D. Unifying access. Transp. Res. D 83, 102355 (2020).

Moya-Gómez, B. & García-Palomares, J. C. Working with the daily variation in infrastructure performance on territorial accessibility. The cases of Madrid and Barcelona. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 7, 20 (2015).

Farber, S., Morang, M. Z. & Widener, M. J. Temporal variability in transit-based accessibility to supermarkets. Appl. Geogr. 53, 149–159 (2014).

Fransen, K. et al. Identifying public transport gaps using time-dependent accessibility levels. J. Transp. Geogr. 48, 176–187 (2015).

Imani, A. F., Miller, E. J. & Saxe, S. Cycle Accessibility and Level of Traffic Stress: A Case Study of Toronto. Technical Report. (Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, 2018).

Murphy, B. & Owen, A. Implementing low-stress bicycle routing in national accessibility evaluation. Transp. Res. Rec. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198119837179 (2019).

Wu, H., Levinson, D. & Sarker, S. How transit scaling shapes cities. Nat. Sustainabil. 2, 1142–1148 (2019).

Wu, H. et al. Metadata record for the manuscript: urban access across the globe: an international comparison of different transport modes. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13476867 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The data collection for Chinese cities was funded by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant no. XDA19040402). Data collection and accessibility estimates for Brazilian cities were funded by the Access to Opportunities Project at the Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea). Data collection and accessibility estimates for cities in the Netherlands were funded by the ASTRID—accessibility, social justice and transport emission Impacts of a transit-oriented Development project (NWO project number: 485-14-038). The Canadian travel times and data collection was funded by the Social Sciences Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Andrew Byrd of Conveyal helped prepare the input data and interpret results for Paris. Christian Quest of OpenStreetMap France processed the 2019 SIRENE database used for Paris job numbers. We knowledge the support of the Polish National Science Centre, within the POLONEZ program, allocated on the basis of decision No. UMO-2015/19/P/HS4/04067 based on the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 665778. US Data are from the Accessibility Observatory, funded by the National Accessibility Evaluation. Data collection and analyses for Australia and New Zealand were supported by TransportLab. Transit GTFS data for Douala, Cameroon, as well as the initial job distribution estimation for the African cities, were contributed by the World Bank and financially supported by UKAID/DfID through the Multi-donor Trust Fund on Sustainable Urbanization. We thank the above institutes and individuals for their generous contribution of data and funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: D.L.; analysis and interpretation of results: H.W.; draft paper preparation: H.W.; accessibility calculation for respective nations/cities: H.W., P.A., G.B., C.B., A.E., J.H., T.K., B.M., M.N., R.P., J.P., A.S., and J.W. There is no difference in contribution between authors providing accessibility calculation for different nations/cities. All authors reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Avner, P., Boisjoly, G. et al. Urban access across the globe: an international comparison of different transport modes. npj Urban Sustain 1, 16 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-021-00020-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-021-00020-2

This article is cited by

-

Energy and environmental impacts of shared autonomous vehicles under different pricing strategies

npj Urban Sustainability (2023)