Abstract

Dissipative optical solitons of particle-like structures can form soliton molecules with striking molecule-like interactions. However, the experimental investigation of soliton molecules in ultrafast lasers is still largely confined to bound states of only two solitons and is far from being explored for soliton molecular complexes. Here, the reconfigurable switching of soliton molecular complexes originating from the binding of two soliton-pair molecules was demonstrated around 2 μm, simultaneously opening an emerging window in the longer wavelength. The periodic switching of soliton molecules with dual-stability can be resolved. Moreover, the single and multiple successively switching of soliton molecules can be triggered by the collision of drifting soliton or control over saturable absorption parameters. Further, the consecutive reversible switching with high fidelity is verified in soliton molecules with periodic pump modulation. These results unveil the dynamical soliton interaction and motivate potential applications in ultrafast spectroscopy, information encoding, and computations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solitons, as wave packets localized in time and space, have attracted numerous research attention in biology, fluid dynamics, plasma physics, and photonics1,2,3,4. In the original studies, solitons were attributed to the solutions to integrable Hamiltonian systems like the self-focusing in 1D nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLSE), lately, the initial concept has been extended to nonlinear dissipative systems, in which the dissipative soliton arises from the balance between dispersion and nonlinearity, and between gain and loss5. The mode-locked fiber laser, as an absolutely dissipative system, constitutes an ideal testbed to study multiple dissipative soliton interactions6,7,8. Even the ultraweak interactions can be observed within the virtually unlimited propagation time9. Further, dissipative soliton interactions lead to a variety of self-organized structures, from regular patterns such as passive harmonic mode-locking to chaotic distributions, e.g., soliton rain and optical rogue waves10,11,12,13. Currently, multiple soliton interactions like collision and even binding to form stable soliton molecules are the subjects of intense studies in laser physics by utilizing the real-time measurement technique14,15,16,17,18,19,20. For instance, the supramolecular structures in photonic crystal fibers and soliton crystallization in micro-cavities show dynamics similar to matter molecules21,22. Such soliton molecules may increase the capacity of telecommunication, which is also attractive in all-optical information storage23,24.

To date, diatomic soliton molecules that bound states of only two solitons have been the most studied multisoliton structure25,26,27,28,29. Contrary to the significant progress in the diatomic soliton molecules, the controllable multiple-state switching of soliton molecular complexes (SMC) with different temporal spacing and phases is still largely unexplored, especially in the 2-μm fiber lasers. The development of mode-locked fiber lasers in wavelength ranges from 2 μm and beyond is accelerating, driven by applications in medicine, environmental sensing, and material processing30,31,32. However, the fundamental studies of soliton dynamics in 2-μm fiber lasers are far from being explored. Some recent studies report the stable molecular complexes mainly on the 1.5 μm mode-locked fiber laser, e.g., triplet soliton molecule33, oscillating (2 + 2) SMC34, long-range synchronization of two oscillating soliton molecules separated by several nanoseconds35, and self-sustained breathing SMC36. As we know, the differences in the medium gain characteristics in different wavelength ranges (thulium and Erbium-doped fiber), especially gain bandwidth and excited-state relaxation timescales, could play an important role in the dynamical soliton interaction. For instance, the strong anharmonicity could be observed in the vibration soliton-pair molecule at the wavelength of 2 μm while not being observed at 1.5 μm25,26, which calls for additional comparisons with dynamics observed at different operating wavelengths. Furthermore, The rapid multi-state switching of soliton molecules is attractive for application in ultrafast spectroscopy, information encoding, and logic operations, including counting, memory, and all-optical soliton shift registers. The switching in diatomic soliton molecules with varied temporal intervals can be controlled by direct electronic modulation of the semiconductor pump source37 or pulse shaping by changing the second-order group-velocity dispersion and dispersion losses23. In contrast, the controllable temporal spacing and phase in SMC can achieve higher dimensional encoding compared to diatomic soliton molecules, which is beneficial for performing dense encoding in optical communications, imaging, and computations.

In this work, we report the reconfigurable switching of SMC containing four and five pulses in an ultrafast thulium fiber laser with a wavelength of 2 μm. Specifically, the periodic switching of soliton molecules with dual-stability was revealed where two dissipative soliton solutions coexist with different spectrums and pulses separation, which is critical depending on the proper minimum loss spectrum and nonlinear gain. Moreover, the single and multiple switching of SMC could be triggered by the collision of drifting soliton and altering saturable absorption parameters. Numerical simulations of the laser model support the experimental findings, demonstrating the multi-stability of the Tm-doped fiber laser system in which different dissipative soliton solutions can coexist. Further, the consecutive switching with high fidelity was verified in SMC with periodic pump modulation, demonstrating reversible all-optical pulse control.

Results

Experimental results

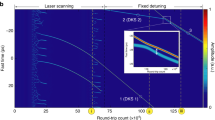

The experimental setup for generating SMC is a thulium-doped mode-locked fiber laser with anomalous path-averaged cavity dispersion [Fig. 1c]. The mode-locking relies on the nonlinear polarization rotation (NPR) technique, which is realized by including two polarization controllers (PC) and a polarization-dependent isolator. Simply rotating the PC allows us to change the transmission function of the saturable absorber (SA), simultaneously modifying the linear cavity loss, thereby modifying the interactions among solitons. The output signal from the laser is recorded in real-time by the time-stretch dispersive Fourier transform (TS-DFT) technique with sub-nanometer resolution38,39,40. A custom-made linearly chirped fiber Bragg gratings (CFBG) was used to circumvent the kilometer-long propagation in dispersive silica fiber that would entail crippling linear losses. Besides the CFBG, the device of free-space angular-chirp-enhanced delay (FACED) is also suitable to provide sufficient dispersion that has been demonstrated in a 2 μm spectrally-encoded microscope41. In this work, SMC exhibits different bound states corresponding to distinct temporal spacing and phase. Using a fiber-coupled intensity modulator (FIM), the consecutive switching with high fidelity of oscillating soliton molecular complexes (OSMC) could be resolved by periodic pump modulation with multiple drops, suggesting applications in ultrafast optical sampling and pulses control [Fig. 1a]. Meanwhile, for the reconfigurable switching of (2 + 2 or 2 + 3) OSMC triggered by drifting soliton collision or variation saturable absorber parameters, the information containing the relative phases φ and temporal separations τ between constituent solitons can be retrieved through the methods of spectral interferometry [Fig. 1b].

a External electronic modulation is implemented using a fiber-coupled intensity modulator (FIM) in the pump beam. Control patterns are generated from arbitrary electronic waveforms driving the FIM. b Schematic representation of the reconfigurable switching and internal degrees of freedom of the soliton molecular complexes containing four or five solitons. c Schematic of the fiber laser and real-time detection system. WDM wavelength division multiplexer, PC polarization controller, PDI polarization-dependent isolator, SMF single-mode fiber, TDF thulium-doped fiber, OC optical coupler, FBG fiber Bragg grating, Circ circulator, PD photodetector.

Periodic switching of OSMC with dual-stability

The mode-locked fiber laser works in a stable single-pulse regime with a pump power of 450 mW. When the pump power increase to 650(750) mW, four(five) pulses are generated per cavity roundtrip. In this experiment, we modified the nonlinear transmission function to alter the pulse interactions through the rotation of the PCs to generate OSMC at fixed pump power. Figure 2a shows the spectrum evolution of oscillating soliton quartet molecule with near-equal temporal separation. The periodic interference fringe variation indicates the switching of soliton molecules with a period of 120 RTs, which is different from the reported (2 + 2) SMC following constant oscillating phase evolution34. The shot-to-shot field autocorrelated traces suggest the side lobe periodic splitting characterizing the soliton molecule switching behavior [Fig. 2b]. In contrast, such periodic splitting was not observed in the recently reported breather molecular complexes36.

a–d Periodic switching of oscillating soliton quartet molecule. e–h Periodic switching of oscillating soliton quintet molecule. i–l Periodic switching of (2 + 3) oscillating soliton molecular complexes. a, e, i The real-time spectral evolution measured via DFT. b, f, j The corresponding field autocorrelation traces. The temporal pulse distribution in (c, g, k) and single-shot spectrum in (d, h, l) of several typical RTs corresponds to the black dashed lines in (b, f, j), respectively.

Although the temporal separation in the soliton quartet molecule is less than the temporal resolution of 80 ps which impedes the direct observation of pulse distribution in the time domain, the temporal pulse distribution can be determined by analytic fit according to the autocorrelation traces. Note that if the pulse bunch contains n pulses with equal temporal separation, its field autocorrelation trace features 2n − 1 peak. The unequally spaced molecules possess relatively complicated autocorrelation traces owing to the complex multipulse structures. In the analytical fit process, each soliton in soliton molecules was sech pulse profile with a temporal width of 500 fs. Here, the intensity of the pulses was neglected in the calculation, and the temporal pulse separation was inferred from the autocorrelation traces [dashed line in Fig. 2b]. The analytical fit temporal pulse distribution [Fig. 2c] indicated periodic switching of the soliton quartet molecule from the near-equal temporal separation of 10.8 ps corresponding to seven peaks in autocorrelation traces (state 1 at RT 200) transition to unequal temporal separation (state 2 at RT 265). The soliton quartet molecule from state 1 switching to state 2 with a smaller temporal separation corresponding to a variational inference fringe interval in the spectrum [Fig. 2d], which also indicates the decrease of binding potential and attractive interaction in soliton molecules during switching. Similarly, the periodic switching behavior of soliton quintet molecule and (2 + 3) OSMC could be observed in Fig. 2e–l, respectively. The corresponding detailed experimental description can be found in the Method section.

Single switching of OSMC with drifting soliton collision

Another notable switching process of (2 + 2 and 2 + 3) OSMC is illustrated in Fig. 3 with the collision of drifting soliton. The drifting solitons are stochastically born in the background noise constituted by quasi-CW components, and then drift until they crash into a condensed soliton phase (OSMC). The real-time spectra evolution of drifting soliton buildup and corresponding non-dispersive temporal intensity evolution can be found in Supplementary Note 1. The DFT spectral and corresponding field autocorrelation traces of (2 + 2) OSMC single switching are shown in Fig. 3a, b. We can find that the drifting soliton [Fig. 3a] is formed from the background noise after the soliton molecules formation by properly adjusting the polarization in the laser cavity. The generated drifting soliton first undergoes spectral broadening, then collides with the OSMC, and eventually vanishes. By tracking the drift motions, the drifting soliton firstly experiences a dynamic accumulation stage with energy gradually increasing, and then drifts at a constant rate that is distinct from the group velocity of the OSMC. The soliton drifting behavior is speculated to be regulated by the Casimir-like interactions42.

a–d Switching of (2 + 2) oscillating soliton molecular complexes. a The real-time spectral evolution measured via DFT. b The corresponding field autocorrelation traces. c The temporal pulse distribution of several typical RTs corresponding to the black dashed lines in (b). d Retrieved relative phase of soliton molecules corresponding to dashing lines in (a). e–h Switching of (2 + 3) oscillating soliton molecular complexes. e The real-time spectral evolution measured via DFT. f The corresponding field autocorrelation traces. g The temporal pulse distribution of several typical RTs corresponding to the black dashed lines in (f). h Retrieved relative phase of soliton molecules corresponding to dashing lines in (e).

During the collision, the drifting soliton is devoured, and the energy of the soliton molecule increases accordingly. Meanwhile, the OSMC will release one part of the energy to reshape to a new steady-state from the (2 + 2) OSMC with a sliding phase switching to soliton quartet molecules with near-equal temporal separation and oscillating phase evolution [Fig. 3c, d]. No pulse breakup or annihilation occurs, which significantly differs from the breather collision and annihilation in breather molecular complexes36. The analytical fit temporal pulse distribution [Fig. 3c] in (2 + 2) OSMC suggests the temporal separation of 6.7 ps (11.9 ps) in the leading (trailing) soliton-pair molecule before switching [RT 1000 in Fig. 3c]. The initial intermolecular separation of 29.3 ps slightly decreases during switching from RT 1000 to RT 3950 [RT 3950 in Fig. 3c], then the soliton molecules transit to a soliton quartet molecule with a smaller intermolecular separation of 12.3 ps [RT 7000 in Fig. 3c].

Concerning the ultrafast laser that carves each pulse profile similarly, the most relevant internal variables are the relative phases and temporal separations among solitons. Besides the pulse separations τi = 1,2,3 [Fig. 3c], the relative phases φi = 1,2,3 among pulses can also be retrieved from the interference fringes of the recorded real-time DFT spectra [Fig. 3d]. For the internal dynamics in (2 + 2) OSMC before switching, the relative phase φ1 in the leading soliton-pair molecule indicates a fixed oscillating phase evolution. Meanwhile, the φ2 and φ3 show the sliding phase evolution that the relative phase between leading and trailing soliton-pair molecules continuously increases, accompanying periodic oscillation. The same oscillating period 162 RT of φ1, φ2, and φ3 could be resolved during the phase evolution. Further, the relative phase of the soliton quartet molecule after switching could be retrieved [Fig. 3d], which is significantly different from the before-switching state. The internal dynamics with soliton molecules are dominated by the oscillation of the relative phases, with a period of 128 RT. The relative phases of φ1, φ2, and φ3 both in phase oscillation, which mainly oscillates between two fixed turning points.

Likewise, the single switching of (2 + 3) OSMC triggered by the drifting soliton collision could be observed in Fig. 3e–h. The corresponding detailed experimental description can be found in the Method section.

Multiple switching of OSMC

Besides the switching induced by drifting soliton collision, the multiple switching of (2 + 2 and 2 + 3) OSMC could be triggered by altering saturable absorption parameters. The multiple switching of (2 + 2) OSMC is shown in Fig. 4a–c. The DFT spectra and field autocorrelation trace evolution [Fig. 4a, b] indicate the OSMC experience four different stages during this multiple switching process. The analytical fit temporal pulse distribution [Fig. 4c] suggests different temporal separations of the (2 + 2) OSMC in four stages. Firstly, the (2 + 2) OSMC with sliding phase evolution corresponds to an intermolecular temporal separation of 30.6 ps (oscillating period 165 RT in state 1). Then the OSMC switches to the oscillating soliton quartet molecule with near-equal temporal separation (oscillating period 180 RT) and oscillating phase evolution. The intermolecular temporal separation significantly decreases to 10.2 ps (state 2). Sequentially, the oscillating soliton quartet molecule transition to stationary soliton molecules (state 3), and finally recover to a (2 + 2) OSMC with sliding phase evolution (state 4) and an evident increase of intermolecular temporal separation to 40 ps (oscillating period 390 RT). Similarly, the multiple switching of (2 + 3) OSMC is shown in Fig. 4d–f. The corresponding detailed experimental description can be found in the Method section.

a–c Multiple switching of (2 + 2) oscillating soliton molecular complexes. a The real-time spectral evolution measured via DFT. b The corresponding field autocorrelation traces. c The temporal pulse distribution of several typical RTs corresponding to the black dashed lines in (b). d–f Multiple switching of (2 + 3) oscillating soliton molecular complexes. d The real-time spectral evolution measured via DFT. e The corresponding field autocorrelation traces. f The temporal pulse distribution of several typical RTs corresponding to the black dashed lines in (e).

Consecutive switching of OSMC with periodic pump power modulation

Furthermore, the external electric control of OSMC could be achieved by applying a strong stimulus with periodic pump modulation that abruptly decreases the pump power in each period. The pump power was modulated by an FIM with an adjustable period and a 2% duty ratio (see Supplementary Fig. 9). Figure 5a, b show the DFT spectra and corresponding field autocorrelation evolution of the (2 + 2) OSMC consecutive switching under periodic pump power modulation with a modulation depth of 70% and modulation frequency of 20 kHz. The analytical fit temporal pulse distribution [Fig. 5c] indicates the OSMC continuously switching between two states with different temporal separations. The rapid drop of 70% in the pump power disrupted the bound state, resulting in the variation of its binding temporal. The pulse interval between two soliton-pair molecules firstly fast decreases from 33.7 to 29.6 ps during switching with pump power drop, and the solitons in leading and trailing soliton-pair molecules both repel corresponds to binding potential increase. Upon recovery of the pump power, the (2 + 2) OSMC with sliding phase evolution was re-established with the same pulse interval and oscillating period as the initial state. Subsequent application of the identical stimulus triggers the OSMC consecutive switching that enables a reversible and deterministic switching between the two SMC states.

a–c Consecutive switching of (2 + 2) OSMC with a modulation frequency of 20 kHz. d–f Consecutive switching of oscillating soliton quintet molecule with a modulation frequency of 20 kHz. g–i Consecutive switching of (2 + 2) OSMC with a modulation frequency of 5 kHz. a, d, g The real-time spectral evolution measured via DFT. b, e, h The corresponding field autocorrelation traces. c, f, i The temporal pulse distribution of several typical RTs corresponding to the black dashed lines in (b, e, h), respectively.

The individual switching process evolved in a highly reproducible manner, further evidenced by the more DFT and field autocorrelation evolution with the same trajectories. Likewise, the consecutive switching of the soliton quintet molecule and (2 + 2) OSMC between triple states could be observed in Fig. 5d–i, respectively. The corresponding detailed experimental description can be found in the Method section.

By observing the fidelity of the final state after applying several hundred events in a separate measurement, the consecutive reversible switching with high fidelity was further verified at more different bound states with different pump modulation depths and frequencies. These results demonstrate the realization of fast SMC control with a 20 kHz switching speed in the oscillator via gain modulation. We also anticipated that the higher repetition rate pump modulation in the ultrashort cavity with GHz repetition rate would greatly increase switching speeds. This method presents an alternative path to implementing controllable multisoliton manipulation in versatile laser cavities, and simultaneously opens an emerging window in the longer wavelength. Moreover, the dynamic response of soliton molecules under frequency-swept excitation is revealed (see Supplementary Note 7). Besides the dominating linear response of the phase evolution in soliton molecules, the different signatures of nonlinear dynamics containing the excitation of higher-order harmonic frequencies have also been observed in the 2 μm fiber laser.

Numerical simulation

To provide insight into SMC switching in the 2–μm mode-locked fiber laser, the numerical simulations were executed based on the lumped propagation model, where each cavity component is modeled by a separate equation43,44. The gain fiber modeling includes gain saturation, bandwidth limitation, and longitudinal dependence of saturation, quantities depending on the pump power Pp. The experimental results indicate that the assembled forms of soliton molecules are closely related to the pump power, polarization setting, and initial pulse conditions. Thus, adjusting the parameters Pp, q0, and Psat in simulation is equivalent to changing the pump power and polarization, which could modify the interactions among pulses in soliton molecules. More details of the modeling are presented in the Method section.

For the parameters set defined with Pp = 150 mW, q0 = 0.5, Psat = 50 W, the periodic switching of soliton quartet molecule with dual-stability could be observed with suitable gain modulation. As seen in Fig. 6a, the periodic variation of interference fringe indicates the switching behavior of soliton molecules. The corresponding field autocorrelations traces are synchronously displayed in Fig. 6b. Here, the zoom-in autocorrelation traces corresponding to the right half clearly show the detailed temporal evolution in which side peaks periodic splitting as a unique characteristic of soliton molecule switching behavior, reproducing the experimental results [Fig. 2b] convincingly. The temporal pulse distribution [Fig. 6f] indicated the periodic switching of soliton quartet molecule from near-equal temporal separation corresponding to seven peaks in autocorrelation traces (state 1 at RT 1215) switch to unequal temporal separation (state 2 at RT 1350), which agrees well with the experimental result [Fig. 2c].

Evolution of a Spectrum and b corresponding field autocorrelation traces. c Color map of the net gain coefficient variation with the number of cavity roundtrips. d Roundtrip dependent means by averaging the net gain coefficients ranging from 1960 to 1980 nm. e evolving trajectories in the plane constructed by the square root of the spectra moment and pulse energy. f The temporal pulse distribution of several typical RTs corresponds to the black dashed lines in (b).

The unique gain spectra evolution characteristic of the soliton quartet molecule during switching is shown in Fig. 6c (details of the calculation gain evolution are presented in the Method section). The ensemble average of the net gain coefficient [Fig. 6d] further confirms the gain spectrum with periodic variation is the key factor resulting in the self-sustained switching of the soliton molecule. Meanwhile, the evolving trajectories in the plane are constructed by the square root of the spectra moment and pulse energy [Fig. 6e] indicates the soliton molecule periodic switching between two attractors with different pulses energy and spectrum, which demonstrate the dual-stability of the 2-μm laser system that two dissipative soliton solutions can coexist in the Tm-doped ultrafast fiber laser.

The simulation of SMC switching with drifting soliton collision is shown in Fig. 7a–h. For the parameters set defined with Pp = 161 mW, q0 = 0.5, Psat = 51 W, the (2 + 2) SMC with sliding phase evolution could be observed. The sliding phase can be resolved in the spectrum that spectral fringe sliding toward higher frequencies as roundtrips increase [Fig. 7a]. The temporal intensity evolution of SMC before switching is shown in Fig. 7b. Then, a drifting soliton with small intensity in the time domain was added to the stable SMC to trigger the soliton molecule switching behavior [Fig. 7d]. As seen in Fig. 7f, the drifting soliton collision with the SMC and then annihilation, the SMC from the sliding phase switching to an oscillating phase state [Fig. 7e]. Simultaneously, the pulse interval in SMC has a variation after switching. The relative phase could be observed in the zoom-in spectrum that spectral fringe periodic oscillating as roundtrips increased [Fig. 7e corresponds to the dashed rectangle in Fig. 7f]. After the perturbation of drifting soliton, the average net gain coefficient shows a significant irregular vibrate, then coverage to a stable oscillating state [Fig. 7h]. The zoom-in net gain coefficient [Fig. 7g] exhibits regular periodic modulation that is different from the sliding phase evolution [Fig. 7c], which indicates the conspicuous gain spectrum variation of soliton molecules during SMC switching with drifting soliton collision.

a–h Simulation of SMC switching with drifting soliton collision. Evolution of a spectrum and b temporal intensity of soliton molecules before switching. c The variation of average net gain coefficient in the range between 1960 to 1980 nm with the number of cavity roundtrips. d Temporal intensity of soliton molecule with drifting soliton collision. Evolution of e spectrum and f temporal intensity of soliton molecules after switching. g, h The variation of average net gain coefficient in the range between 1960 to 1980 nm with the number of cavity roundtrips after switching. i–l Simulation of SMC switching with variation saturable absorber parameters. Evolutions of the spectrum and temporal intensity of soliton molecules in (i, j) switching from oscillating phase to stationary state, (k, l) switching from stationary to sliding phase state.

Further, the simulation of (2 + 2) SMC switching with variation saturable absorber parameters is shown in Fig. 7i–l. With q0 = 0.5, Psat = 49 W, and different initial conditions, Fig. 7i,j show the spectrum and temporal intensity evolution of (2 + 2) SMC switching from oscillating phase to stationary state, and Fig. 7k, l show the SMC switching from stationary to sliding phase evolution. These switching processes are qualitatively closed to the experimentally observed multiple switching of soliton molecules [Fig. 4a, b]. Similarly, the simulated result of (2 + 3) SMC can be found in Supplementary Note 8. The calculation of gain spectrum evolution and evolving trajectories in the plane constructed by the square root of the spectra moment and pulse energy further reveal the (2 + 2) and (2 + 3) SMC switching behavior (see Supplementary Note 9). The SMC switching between different operation state involve stationary, oscillating, and sliding phase evolution corresponding to different gain spectrum evolution and attractor.

Discussion

The remarkable property of dissipative soliton is the ability to form robust multiple-bound states, and the ultrafast fiber laser cavity constitutes an ideal propagation medium to study multiple soliton interactions in soliton molecules. The overall pattern of the SMC depends on the interplay among various interaction mechanisms. Specifically, the periodic switching of soliton molecules with dual-stability where two dissipative solutions coexist corresponds to distinct spectrum and pulses temporal separation, which is critical depending on the periodic gain spectra evolution between two different states. Such self-sustained switching behavior further demonstrates the multiple-stability of the 2-μm fiber laser system.

Moreover, the different types of switching in SMC could be triggered with external perturbations that result in conspicuous gain spectrum variation, in which the temporal spacing and phase of soliton molecules are varied during switching. Specifically, the single switching of (2 + 2) and (2 + 3) SMC could be achieved with the collision of drifting soliton. The SMC from sliding phase switching to oscillating phase evolution with different temporal spacing. It is also interesting to note that externally injected signals through electro-optic modulation could replace the drifting soliton that may serve as an alternative way to control SMC reconfigurable switching. Meanwhile, the multiple switching of SMC could be triggered by altering saturable absorption parameters through polarization manipulation. The soliton molecules could successively switch between the sliding phase, oscillating phase, and stationary state with different temporal separations. Numerical simulations reveal that the gain spectrum of SMC changes conspicuously during switching corresponds to different operation states and attractors. Further, the consecutive reversible switching with high fidelity was verified in SMC with periodic pump modulation, demonstrating reversible pulse control in the oscillator. Besides the multiple drop waveform [Fig. 1a], the more complex periodic pump modulation could be designed according to the particular net gain coefficient evolution that would be helpful to achieve SMC switching in a different phase and temporal interval.

Furthermore, compared to the switching in diatomic soliton molecule which the soliton coupling mechanism is based on linear reflections37, the different pulse temporal separation, and phase in multiple switching of SMC are dominated by gain modulation rather than the linear reflection. Please note that the reconfigurable switching of soliton molecules can be achieved in a broad range of ultrafast nonlinear systems, e.g., the assembling supramolecular structures of optical solitons in a fiber laser by using intense optoacoustic effects in photonic crystal fibers, and the multimode fiber systems that provide an extra degree of freedom in the control of coherent in space domain21,45. We anticipate that the rapid multi-state switching of SMC will provide potential ultrafast spectroscopy and logic operation applications. Meanwhile, our observations unveil the dynamic interaction of soliton molecules and will provide valuable insights into laser design and application.

Methods

Experimental setup

The soliton molecules comprising four or five solitons are generated from a thulium-doped fiber (TDF) ring laser, mode-locked by the nonlinear polarization rotation (NPR) technique. The nonlinear transfer function could be tuned within the laser cavity by adjusting the polarization controller (Fig. 1) and thus as a quasi-instantaneous saturable absorber. The 12.1 m long ring cavity includes 3 m of thulium-doped fiber (TSF-9-125) with group-velocity dispersion (GVD) of about −83 ps2/km and 9.1 m SM28-e fiber with a GVD of ~ −71 ps2/km which is pumped by the laser source at 1560 nm. The net cavity dispersion is ~−0.9 ps2 and corresponds to a fundamental repetition rate of 16.5 MHz. A bandpass filter was inserted into the cavity to fix the optical spectrum with a central wavelength of 1970 nm. A coupler with a 30/70 splitting ratio was used to extract 30% power of pulses for measurement. The model number of key components in the mode-locked fiber laser can be found in Supplementary Note 10. The temporal information (undispersed) was detected by a 12 GHz photodiode (PD1 ET-5000F) and digitized by a 20 GHz real-time oscilloscope (Lecroy SDA 820Zi-B), while the spectra were recorded by an optical spectrum analyzer (OSA, YOKOGAWA AQ6375) and TS-DFT technique simultaneously. The DFT branch was composed of a custom-made chirped fiber Bragg grating (CFBG) from TeraXion with 300 ps/nm dispersion and a flat reflection band of 30 nm between 1955 and 1985 nm. The DFT signal was detected by another 12 GHz photodiode (PD2, ET-5000F). The temporal and spectral resolution was ~80 ps and 0.29 nm46, respectively. In this experiment, the number of pulses was controlled by changing pump power, and the interaction among pulses was controlled by maneuvering intracavity polarization, e.g., pulses' temporal separation and oscillation amplitude. Due to the hysteresis and multi-stability in the evolution of ultrashort pulses, the suitable control parameters are not unique, and exist in a relatively wide range. For instance, the (2 + 3) OSMC is found in the 750–800 mW pump power range, also depending on the specific polarization setting. Multiple soliton pairs usually appear first. Then the pulses can be manipulated as units by fine-tuning the control parameters that affect their long-range interactions. Thus, the (2 + 3) OSMC could be generated.

Periodic switching of OSMC with dual-stability

The periodic switching behavior could be observed in the soliton quintet molecule with a switching period of 115 RTs. The spectra evolution and corresponding field autocorrelation traces [Fig. 2e, f] indicate the switching with periodic variation in interference fringe on the spectrum and side-peak splitting in the autocorrelation traces. The temporal pulse distribution and single-shot spectrum [Fig. 2g, h] disclose the switching of soliton quintet molecule from near-equal temporal separation 9.9 ps (state 1 at RT 255) transition to unequal temporal separation with a smaller pulses interval (state 2 at RT 300).

Further, for the more complex switching of (2 + 3) OSMC with a switching period of 104 RTs, the periodic interference fringe varies could be resolved in the spectrum evolution [Fig. 2i, l]. However, the only part of side-peak periodic splitting in the autocorrelation traces [Fig. 2j] is slightly different from the oscillating soliton quartet and quintet molecule. The analytical fit temporal pulse distribution [Fig. 2k] indicated that the temporal interval of the leading soliton-pair molecule does not change during switching. Meanwhile, the first soliton in the trailing soliton-pair molecule is repulsive, and the second and third soliton attraction compares to the leading soliton-pair molecule, indicating a more complex binding potential variation during switching (from RT 245 to RT 310). These observations in soliton quartet and quintet molecule, and (2 + 3) OSMC further demonstrate that self-sustained switching is a common dynamical attractor in the 2-μm fiber laser that the different soliton assembles forms suggest similar periodic switching behavior47,48.

Single switching of OSMC with drifting soliton collision

The single switching of (2 + 3) OSMC could be triggered by the drifting soliton collision. The spectra and field autocorrelation traces evolution [Fig. 3e, f] indicate the (2 + 3) OSMC transition to the soliton quintet molecule with near-equal temporal separation. The analytical fit temporal pulse distribution [Fig. 3g] in (2 + 3) OSMC suggests the intermolecular temporal separation of 42.7 ps before switching [RT 1000 in Fig. 3g], then the intermolecular separation fast decreases to 36 ps during switching corresponds to an attractive interaction [RT 5900]. Finally, the (2 + 3) soliton molecules transition to a soliton quintet molecule with intermolecular temporal separation further decreased to 12.6 ps, corresponding to the smaller binding potential [RT 10000]. The significant varies in the intermolecular temporal separation from 42.7 to 12.6 ps demonstrates that the bond between the two soliton-pair molecules that constitute the molecular complexes is weaker than the bond between the two solitons that make up each soliton-pair molecule.

Further, the relative phases φi=1,2,3,4 among pulses can be retrieved from the fringes of the recorded real-time DFT spectra [Fig. 3e]. For the internal dynamics in (2 + 3) SMC before switching, the SMC suggests a sliding phase evolution in which the relative phase between leading and trailing soliton-pair molecules continuously increases, accompanying periodic oscillation. The same oscillating period 265 RT of φ1, φ2, φ3, and φ4 could be observed during the phase evolution. Further, the relative phase of the soliton quintet molecule after switching discloses the internal dynamics are dominated by the oscillating of the relative phases, with a period of 106 RT. The relative phases of φ2, φ3, and φ4 are both oscillating in phase, while φ1 between two solitons in the leading soliton-pair molecule is oscillating out of phase relative to φ2, φ3, and φ4. The evolution trajectory in the interaction plane of the (2 + 2 and 2 + 3) OSMC switching, including pulses temporal separation τi and relative phases φi can be found in Supplementary Note 2. The analytical fits for the internal dynamics of OSMC with oscillating and sliding phase evolution can be found in Supplementary Note 3. We can also find this nonlinear single collision process is similar to the simplified soliton rain49, except that the complex condensed soliton phase is substituted with an OSMC. It is interesting to note that the energy of the OSMC is significantly higher than that of the drifting solitons, which means they correspond to different attractors in the dissipative system.

Multiple switching of OSMC

The DFT spectra and field autocorrelation trace evolution of (2 + 3) OSMC [Fig. 4d, e] indicate the soliton molecule experiences six different switching processes. The analytical fit temporal pulse distribution [Fig. 4f] shows the distinct temporal separation of the (2 + 3) OSMC in six stages. Please note that the OSMC at the seventh stage possesses the same oscillating behavior and pulse interval as stage 1, indicating this is a reversible switching process. For the multiple switching detail, firstly, the (2 + 3) OSMC with sliding phase evolution and intermolecular temporal separation 35 ps (oscillating period 117 RT in state 1) transit to a soliton quintet molecule with near-equal temporal separation and oscillating phase evolution (oscillating period 120 RT in state 2). The intermolecular temporal separation fast decreases to 12.1 ps. The quintet molecule switches to another oscillation state with oscillating phase evolution and intermolecular temporal separation of 10.4 ps (oscillating period 150 RT in state 3). Then the soliton quintet molecule recovers to the (2 + 3) OSMC with sliding phase evolution. The intermolecular temporal separation gradually increases (states 4, 5, and 6) with different oscillating behavior, and the temporal spacing between solitons in leading and trailing soliton-pair molecules both slightly change during each switching. Finally, the (2 + 3) OSMC (state 7) reverts to the same oscillatory state as state 1, with the same sliding phase evolution and pulse interval. The detailed spectral and field autocorrelation evolution of (2 + 2 and 2 + 3) OSMC multiple switching are presented in Supplementary Note 4. Moreover, another kind of reversible switching of (2 + 2 and 2 + 3) OSMC can be found in Supplementary Note 5.

Consecutive switching of OSMC with periodic pump power modulation

The consecutive switching of the soliton quintet molecule could be achieved under periodic pump modulation with the same modulation parameter as Fig. 5a. The DFT spectra and corresponding field autocorrelation evolution [Fig. 5d, e] indicate the consecutive switching of soliton molecules between two different states. The pulse interval between the first and second solitons is fixed during switching, while the temporal separation between the third and fifth solitons suggests a decrease [Fig. 5f]. After the pump power restores, the soliton quintet molecule is re-established and returned to the initial state. Further, the continuous switching of (2 + 2) OSMC between triple states was observed under periodic pump modulation with a modulation depth of 55% and modulation frequency of 5 kHz. The DFT spectra and corresponding filed autocorrelation traces [Fig. 5g, h] indicate the continuous switching of OSMC between the three states. The pulse interval between the two soliton-pair molecules gradually decreases during switching [Fig. 5i]. After restoring the pump power, the (2 + 2) OSMC with sliding phase evolution is recovered and returned to the initial state. The single-shot spectrum of soliton molecule consecutive switching between different states can be found in Supplementary Note 6. Further, the high fidelity of soliton molecule consecutive switching is quantified by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient between different evolution periods and can also be found in Supplementary Note 6.

Numerical simulations

Numerical simulation was executed in a lumped propagation model. The propagation of solitons within the fiber section is modeled with a generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation in the scalar approach, which takes the following form:

Where u is the slowly varying electric field moving at the group velocity along the propagation coordinate z; γ and β2 are the Kerr nonlinearity and second-order dispersion coefficients, respectively. In the SMF, we set g = 0. In the case of Tm3+-doped fiber, the spectra response of the gain g(z, ω) is homogeneously broadened in a two-level system when an in-band pump at ~1.6 μm is used; the standard dynamics rate equations are given in the steady-state approximation as

Equations (2a–c) depict the distributed pump power Pp and signal power Ps for discrete wavelengths. NTm denotes thulium ion density along the fiber, and N1 and N2 are the population density of the laser ground and upper-level state, respectively. The parameters of the TDF can be found in ref. 50. We solve Eqs. (2a–c) by means of the standard Runge-Kutta algorithm and obtain the gain coefficient amplitude as g(z, Pav, ω) = d(lnPs)/dz, where\({P}_{av}(z)=\frac{1}{{\tau }_{RT}}{{\int }_{0}^{{\tau }_{RT}}|u(z,t)|}^{2}dt\). Therefore, the calculated gain coefficient includes the saturation effect, and the spectral and longitudinal dependences of the amplification process in the TDF.

The saturable absorber in the NPR mode-locking fiber laser is modeled by a nonlinear transmission function: T = T0 + q0 (1-1/(1 + P/ Psat)), where T0 is the transmissivity at the low signal, q0 is the modulation depth, P is the instantaneous pulse power, and Psat is the saturation power. The experimental situation is emulated by tunneling the control parameters containing pump power Pp, saturation power Psat and modulation depth q0.

Gain evolution of soliton molecules

When considering the dynamic rate equation given in the numerical simulation, the integrated signal power Ps(z, λk) is bridged with the light field u(z,t) using the following equations:

Where F denotes the Fourier transform, Tr represents the roundtrip time. Then, the ω dependent gain g(z, ω) in Eq. (1) for each step is calculated using the following equations:

Where Δz is the spatial step size, Lf is the cavity length. Here, the net gain gnet(ω) is used to evaluate the gain spectrum of pulses evolution.

Moreover, the evolutionary trajectory of the pulses is computed in a two-dimensional bandwidth-energy space (σF, Q) to describe the feature of SMC switching with different operation states. The total energy in the calculated temporal window is defined as\(Q={\int }_{{t}_{1}}^{{t}_{2}}{|u(z,t)|}^{2}dt\). And the spectral width

where f is normalized frequency and \(\langle \,{f}^{n}\rangle\)is defined as \(\frac{1}{Q}{{\int }_{-\infty }^{+\infty }\,{f}^{n}|F[u(z,t)]|}^{2}df\).

Data availability

The data supporting the plots within the paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used in this paper is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dauxois, T. & Peyrard, M. Physics of Solitons (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006).

Denschlag, J. et al. Generating solitons by phase engineering of a Bose-Einstein condensate. Science 287, 97–101 (2000).

Akhmediev, N. & Ankiewicz, A. Nonlinear Pulses and Beams (Chapman & Hall, 1997).

Zabusky, N. J. & Kruskal, M. D. Interaction of “solitons” in a collisionless plasma and the recurrence of initial states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 15, 240 (1965).

Grelu, P. & Akhmediev, N. Dissipative solitons for mode-locked lasers. Nat. Photonics 6, 84–92 (2012).

Akhmediev, N. et al. Dissipative soliton interactions inside a fiber laser cavity. Opt. Fiber Technol. 11, 209–228 (2005).

Tang, D. et al. Soliton interaction in a fiber ring laser. Phys. Rev. E 72, 016616 (2005).

Weill, R. et al. Noise-mediated Casimir-like pulse interaction mechanism in lasers. Optica 3, 189–192 (2016).

Jang, J. K. et al. Ultraweak longrange interactions of solitons observed over astronomical distances. Nat. Photonics 7, 657–663 (2013).

Liu, X. & Peng, M. Revealing the buildup dynamics of harmonic mode-locking states in ultrafast lasers. Laser Photonics Rev. 13, 1800333 (2019).

Solli, D. R. et al. Optical rogue waves. Nature 450, 1054–1057 (2007).

Grudinin, A. B. & Gray, S. Passive harmonic mode locking in soliton fiber lasers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 14, 144 (1997).

Chouli, S. & Grelu, P. Rains of solitons in a fiber laser. Opt. Express 17, 11776–11781 (2009).

Herink, G. et al. Resolving the buildup of femtosecond mode-locking with single-shot spectroscopy at 90 MHz frame rate. Nat. Photonics 10, 321–326 (2016).

Liu, X., Yao, X. & Cui, Y. Real-time observation of the buildup of soliton molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 023905 (2018).

Peng, J. et al. Real-time observation of dissipative soliton formation in nonlinear polarization rotation mode-locked fibre lasers. Commun. Phys. 1, 20 (2018).

Roy, V. et al. Dynamics of periodic pulse collisions in strongly dissipative-dispersive system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 203903 (2005).

Grelu, P. & Akhmediev, N. Group interactions of dissipative solitons in a laser cavity: the case of 2+1. Opt. Express 12, 3184–3189 (2004).

Zhou, Y. et al. Buildup and dissociation dynamics of dissipative optical soliton molecules. Optica 7, 965–972 (2020).

He, W. et al. Synthesis and dissociation of soliton molecules in parallel optical-soliton reactors. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 120 (2021).

He, W. et al. Formation of optical supramolecular structures in a fibre laser by tailoring long-range soliton interactions. Nat. Commun. 10, 5756 (2019).

Cole, D. C. et al. Soliton crystals in Kerr resonators. Nat. Photonics 11, 671–676 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. On-demand harnessing of photonic soliton molecules. Optica 9, 240–250 (2022).

Pang, M. et al. All-optical bit storage in a fibre laser by optomechanically bound states of solitons. Nat. Photonics 10, 454–458 (2016).

Krupa, K. et al. Real-time observation of internal motion within ultrafast dissipative optical soliton molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 243901 (2017).

Hamdi, S., Coillet, A. & Grelu, P. Real-time characterization of optical soliton molecule dynamics in an ultrafast thulium fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 43, 4965–4968 (2018).

Lapre, C. et al. Dispersive Fourier transform characterization of multipulse dissipative soliton complexes in a mode-locked soliton-similariton laser. OSA Contin. 3, 275–285 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Dynamics of dissipative soliton molecules in a dual-wavelength ultrafast fiber laser. Opt. Express 30, 21931–21942 (2022).

Kurtz, F., Ropers, C. & Herink, G. Resonant excitation and all-optical switching of femtosecond soliton molecules. Nat. Photonics 14, 9–13 (2020).

Jackson, S. D. Towards high-power mid-infrared emission from a fibre laser. Nat. Photonics 6, 423–431 (2012).

Delavaux, J.-M. et al. Preface to the Special Issue on short pulse fiber lasers. Opt. Fiber Technol. 20, 561 (2014).

Duval, S. et al. Femtosecond fiber lasers reach the midinfrared. Optica 2, 623–626 (2015).

Luo, Y. et al. Real-time dynamics of soliton triplets in fiber lasers. Photonics Res. 8, 884–891 (2020).

Wang, Z. Q. et al. Optical soliton molecular complexes in a passively mode-locked fibre laser. Nat. Commun. 10, 830 (2019).

Hamdi, S. et al. Superlocalization reveals long-range synchronization of vibrating soliton molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 213902 (2022).

Peng, J. et al. Breather molecular complexes in a passively mode-locked fiber laser. Laser Photonics Rev. 15, 2000132 (2021).

Nimmesgern, L. et al. Soliton molecules in femtosecond fiber lasers: universal binding mechanism and direct electronic control. Optica 8, 1334–1339 (2021).

Goda, K. & Jalali, B. Dispersive Fourier transformation for fast continuous single-shot measurements. Nat. Photonics 7, 102–112 (2013).

Herink, G. et al. Real-time spectral interferometry probes the internal dynamics of femtosecond soliton molecules. Science 356, 50–54 (2017).

Ryczkowski, P. et al. Real-time full-field characterization of transient dissipative soliton dynamics in a mode-locked laser. Nat. Photonics 12, 221–227 (2018).

Tan, S. et al. Flexible pulse-stretching for a swept source at 2.0 µm using free-space angular-chirp-enhanced delay. Opt. Lett. 43, 102–105 (2018).

Sulimany, K. et al. Bidirectional soliton rain dynamics induced by casimir-like interactions in a graphene mode-locked fiber laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 133902 (2018).

Cheng, H. et al. Numerical insights into the pulse instability in a GHz repetition-rate thulium-doped fiber laser. J. Lightwave Technol. 39, 1464–1470 (2021).

Meng, F. et al. Intracavity incoherent supercontinuum dynamics and rogue waves in a broadband dissipative soliton laser. Nat. Commun. 12, 5567 (2021).

Wright, L. G., Christodoulides, D. N. & Wise, F. W. Spatiotemporal mode-locking in multimode fiber lasers. Science 358, 94–97 (2017).

Tsia, K. K. et al. Performance of serial time-encoded amplified microscope. Opt. Express 18, 10016–10028 (2010).

Woodley, M. T. M. et al. Self-switching Kerr oscillations of counter propagating light in microresonators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 043901 (2021).

Bao, C. et al. Observation of coexisting dissipative solitons in a mode-locked fiber laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 253903 (2015).

Liang, H. et al. Real-time dynamics of soliton collision in a boundstate soliton fiber laser. Nanophotonics 9, 1921–1929 (2019).

Khamis, M. A. & Ennser, K. Model for a thulium-doped silica fiber amplifier pumped at 1558 nm and 793 nm. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 5, 76–80 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China (HKU C7074-21GF, HKU 17205321, HKU 17200219, HKU 17209018, and CityU T42-103/16-N) and Health@InnoHK program of the Innovation and Technology Commission of the Hong Kong SAR Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. conceived and performed the most experiments and simulations. K.K.Y.W. supervised and guided the project. Y.Z., J.S., Y.-X.R., and K.K.Y.W. discussed the results and contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Shi, J., Ren, YX. et al. Reconfigurable dynamics of optical soliton molecular complexes in an ultrafast thulium fiber laser. Commun Phys 5, 302 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-01068-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-01068-x

This article is cited by

-

Phase-tailored assembly and encoding of dissipative soliton molecules

Light: Science & Applications (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.