Abstract

The quality factor (Q), describing the rate of energy loss from a resonator, is a defining performance metric for nanophotonic devices. Suppressing cavity radiative losses enables strong nonlinear optical responses or low-power operation to be achieved. Exploiting long-lived, spatially-confined bound states in the continuum (BICs) has emerged from the numerous approaches considered as a promising route to boost nanophotonic Q factors. Initial research explored the formation mechanisms of various types of BICs, drawing parallels to topological physics. With these fundamentals now established, we review the recent application of BICs in passive and active nanophotonic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonradiative states of energy have attracted significant attention in the fields of quantum mechanics, electrodynamics, astrophysics, and photonics. The particular electromagnetic states that originate from oscillating electron configurations do not permit energy propagation outside a localized volume. In 1929, von Neumann and Wigner first mathematically proposed a localized electronic state, despite residing within the continuous spectrum of radiation1. Such nonradiative states are referred to as bound states in the continuum (BICs) and are expected to be used for an artificial quantum potential. In 1985, Friedrich and Wintgen found that the theoretical model of the interference between a pair of resonances with continuous parameters could lead to the complete elimination of the radiative states and facilitate the formation of an electronic BIC2. Since then, this nearly century-old concept from quantum mechanics has rapidly entered other fields.

In photonics, the concept of BICs related to dark optical states has been reported since 20083,4. Although light confined in a resonator generally loses energy due to the inevitable coupling to an external radiation channel, an infinite quality (Q) factor can be realized in optical BICs by isolating the state from the external radiation channel. Optical BICs can be comprehensively understood in the simplest case, Fabry-Pérot BICs, which are composed of two resonant structures5,6. When the two resonators are simultaneously coupled with a single radiation channel, they can interact strongly through radiation, even if they are far apart. Fabry-Pérot BICs are easily observable in structures such as stacked photonic crystal slabs, double gratings, and waveguide arrays with resonant defects3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. On the other hand, two different resonances at the same location can also generate a BIC through the interference of radiative modes. This phenomenon is known as a Friedrich-Wintgen BIC2,11,12,13. The Friedrich-Wintgen BIC occurring in a single resonator is distinguishable from the Fabry-Pérot BIC in the coupled resonator system14. However, in terms of the interference in the same radiation channel, the Friedrich-Wintgen BIC can be considered to be a special case of the Fabry-Pérot BIC, in which the spacing between the two cavities becomes zero.

Expanded approaches to construct various BICs have been suggested in the field of photonics (Fig. 1)15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. In 2011, an optical BIC called a symmetry-protected BIC was experimentally demonstrated in coupled optical waveguides15. A pair of waveguides was added above and below the central waveguide, forming a localized mode whose propagation constant still resides inside the continuous band of array. In this case, no light escapes from the central waveguide into the array due to the antisymmetric mode decoupling from the continuum of the symmetric extended states. After the initial realization of BICs in photonics, numerous geometric systems of gratings, periodic nanowires, metasurfaces, photonic crystals, and cylindrical resonators have been studied. These unique structures implementing BICs provide novel optical feedback mechanisms, including an accidental BIC16, a merging-BIC20, and a quasi-BIC in a single resonator22. In addition, the diversity of BIC systems has led to promising passive and active applications. Enhanced Q factors in BICs were used to boost the nonlinear optical process and high-harmonic generation efficiency of passive devices18,22. In addition, BICs have been used for new lasing operations by combining them with optical gain materials. Lasers based on BICs provide a unique way to control the directionality, beam shape, high-speed modulation, and energy consumption of a laser17,19,23,24,25.

Experimental demonstrations of optical BICs have been extensively reported since 2011. SHG stands for second-harmonic generation. Reprinted by permission from ref. 15, copyright 2011, reprinted by permission from ref. 16, copyright 2013, reprinted by permission from ref. 17, copyright 2017, reprinted by permission from ref. 18, copyright 2018, reprinted by permission from ref. 19, copyright 2018, reprinted by permission from ref. 20, copyright 2019, reprinted by permission from ref. 21, copyright 2019, reprinted by permission from ref. 22, copyright 2020, reprinted by permission from ref. 23, copyright 2020, reprinted by permission from ref. 24, copyright 2020, and reprinted by permission from ref. 25, copyright 2021.

This review introduces nanophotonic nonlinear and laser devices using optical BICs in various nanostructures, and provides an insightful overview of their recent progress. The formation mechanisms of BICs are discussed briefly in this review, because previous pedagogical reviews introduce this topic in detail14,26. Nonlinear optical processes, including second-harmonic generation and third-harmonic generation (SHG and THG), are enhanced by single or periodic array of dielectric nanoantenna. The sharp resonance and strong light confinement originated from BICs are exploited for highly sensitive refractometer sensors. In addition, the combination of BICs and gain materials enables promising laser properties such as directional lasing, high-speed modulation, beam shaping, threshold reduction, and lasing from single nanoparticles. We believe that this review provides a deeper understanding of BICs as a new optical platform with various nanophotonic passive and active applications.

Physical mechanisms of BICs in nanophotonics

Optical BICs can be categorized into several types. This section discusses their operational mechanisms, topological properties, and multipole analyses.

Types of BICs

The concepts of optical BICs have been widely adopted to reduce the energy loss through the radiation channel in various periodic photonic structures such as gratings, photonic crystals, and metasurfaces14,26,27,28,29. Figure 2a illustrates the conventional operating principle of a BIC applied to a waveguide in a one-dimensional (1D) array, which is the simplest form of periodic structure30. Inside the continuum regime, the resonant modes in the straight waveguide are trapped within a high refractive index region, but they lose their energy to open space via the radiation channel. The resonant frequencies of these leaky modes can be simply described by a complex frequency, ω = ω0 – iγ, where the real part, ω0, is the resonance frequency, and the imaginary part, γ, represents the optical loss due to leakage. The leaky guided modes show a non-zero γ, implying an unavoidable optical loss through coupling with the radiation channel. Periodic structures can reduce the leakage through the interference of leaky modes. The forward and backward scattering of leaky modes form a strong coupling at the high-symmetry points, and the fast-decaying mode and non-radiating trapped mode appear as a result of constructive interference and destructive interference, respectively. In particular, the non-radiating trapped mode leads to a BIC that exhibits strong light localization inside the medium and an infinite Q factor with no leakage (γ = 0).

a Calculated optical modes and band structure in a periodic waveguide. BIC modes with infinite radiative Q factors are formed by destructive interference. b Optical BICs in a nanowire geometric superlattice. Structure of a nanowire geometric superlattice (b1), and calculated map of the normalized energy on log scale, with varying pitch for fixed nanowire diameters of 200 nm (outer) and 170 nm (inner) (b2). Reprinted by permission from ref. 21, copyright 2019.

Figure 2b shows a representative example of an optical BIC in a 1D periodic structure21. Optical waves are trapped in the BIC regime above the light cone in single Si nanowire geometric superlattices21,31. According to the theory shown in Fig. 2a, the Mie resonance defined by the nanowire diameter interacts strongly with the external plane wave. A nanowire structure, whose diameters are periodically modulated along the axis, exhibits an additional set of distinct resonant modes. When the nanowire structure satisfies certain geometric conditions, these resonant modes undergo conventional Fano resonances with narrow spectral features. With further geometric tuning, the Fano resonance completely vanishes and reaches an optical BIC. In Fig. 2b, the m = 0 and 1 modes at lattice constants of 237 and 262 nm disappear in the confined energy spectra map, respectively. The resonant guided modes also disappear in the scattering spectra, at the optical BIC condition, indicating the complete dark state for the incident light. In contrast, in the vicinity of the optical BIC, the narrow and bright spectral features are shown in the confined energy spectra map due to the coupling of the Mie resonance and the resonant guided modes.

According to their symmetry, BICs can be classified into two important categories: symmetry-protected BICs and accidental BICs. When a photonic system is preserved by reflection or rotational symmetry, the modes of different symmetry classes completely decouple from other symmetry classes and operate independently in the continuum regime. This phenomenon, which occurs under high-symmetry conditions, is defined as a symmetry-protected BIC32. However, accidental BICs can appear at non-zero wavevectors with additional symmetries33. If a specific symmetry at a non-zero wavenumber becomes invariant in time reversal, in-plane inversion, and up-down mirror symmetries, the additional BIC condition can be satisfied at an arbitrary point in the reciprocal space. For example, in a square-lattice photonic crystal, the accidental BICs appear at the certain direction of off-Γ wavevector in the reciprocal space, where the radiation of vector harmonics of the resonant modes cancels out in the far field26,33. It is difficult to predict the position of the accidental BIC in the parametric space because the condition for the accidental BIC is not dependent on the geometric symmetry of the system. In 2013, Hsu et al. observed two types of BICs in two-dimensional (2D) periodic photonic structures (Fig. 3a)16. Their experiments were performed in a Si3N4 photonic crystal slab with a 2D square array of cylindrical holes. The silica substrate was embedded in a liquid that matched the refractive index of silica. An extremely high radiative Q factor was observed at the Γ point because the symmetry was protected, and coupling to any outgoing wave was forbidden. In addition, the radiative Q factor at ~35° reached 1,000,000 near the instrument resolution limit. This high radiative Q factor presented an additional BIC mode confined at a certain wavevector.

a Symmetry-protected and accidental BICs. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the fabricated BIC structure in top and side views (a1). Normalized radiative lifetime Qr extracted from the measured reflectivity spectrum as a function of the angle (a2). Reprinted by permission from ref. 16, copyright 2013. b Merging-BIC. Schematic of a photonic crystal slab hosting BICs (b1). Far-field polarization plots in the evolution of merging process, from the isolated BIC (left) to merging-BIC (right) (b2). Reprinted by permission from ref. 20, copyright 2019. c Formation of quasi-BIC by strong mode coupling in a high-index dielectric resonator. Reprinted by permission from ref. 35, copyright 2017.

In addition, symmetry-protected and accidental BIC modes can appear as vortex modes confined at nine wavevector points. In 2019, Jin et al. implemented a high-Q photonic crystal cavity in a 600 nm-thick Si photonic crystal slab and found a new BIC mode by merging the symmetry-protected and accidental BIC modes (Fig. 3b)20,34. If the accidental BICs move to the central Γ point until all nine BICs become close to each other, the Q factor under the merging condition can be higher than that in a single isolated BIC along all directions in the momentum space. Notably, such an extremely high Q factor for the merging-BIC, which occurs as a result of the suppressed scattering loss in the momentum space, can overcome the perturbations from defects, disorders, and finite effects.

The optical BICs can also help improving the Q factor of a single subwavelength dielectric resonator in which the conventional Mie resonances suffer from the radiation loss (Fig. 3c)35. The Friedrich-Wintgen theory of BICs reveals that the radiation loss can be suppressed when the destructive mode interference between the two resonances occurs in the far field. As shown in the illustration of a dielectric finite-extent cylindrical resonator, the resonant modes inside a single cylindrical resonator are not purely transverse electric or magnetic, and such a non-orthogonal nature leads to strong coupling between the modes. The interfering resonances by strong coupling result in avoided resonance crossing for the continuous change of the cylindrical geometric aspect ratio (Fig. 3c). Near the avoided crossing regime, the radiating tails of these resonant modes cancel out as a result of destructive interference (dark branch). This results in the rapid growth of the Q factor and realizes the supercavity mode, which is called the quasi-BIC mode. Its Q factor takes a finite value, but is quite high even in a realistic finite size36,37.

Topological properties of BICs in periodic structures

Topological approaches to BICs can elucidate the robustness and enhancement of Q factors16,20,38. For example, symmetry-protected BICs and accidental BICs in periodic extended structures such as photonic crystal slabs preserve their physical characteristics even with moderate variations in the structural parameters (Fig. 3a, b). These two BICs are vortex centers in the polarization direction, showing zero polarization vectors in far-field radiation. They carry conserved and quantized topological charges, q, which are defined by the winding number of the polarization vectors around the vortex centers38. The robustness preserved by the topological charges cannot be eliminated without causing large variations in the structural parameters. Therefore, the existence of these BICs is topologically protected with the conservation of the total topological charges in the momentum space39.

The evolution of BICs, accompanied by continuous changes in the system parameters, was predicted by the conservation rule of topological charges. Small changes in the parameters simply shift the position of these topological charges along the band diagram. Figure 4a shows the evolution of topological charges in a 1D periodic structure38. If the thickness of the grating is reduced while the lattice constant is fixed, the two positive charges in the transverse magnetic-like (TM-like) band become closer to each other but eventually bounce off (charge bouncing). On the other hand, by changing similar parameters, one positive charge and two negative charges meet in the transverse electric-like (TE-like) band, leaving only one negative charge (charge annihilation). In both processes, the total topological charges are conserved within the enclosed winding path of the polarization vector.

a Evolution of BICs and conservation of topological charges. Schematic of a 1D periodic structure and its calculated TM-like band structure (a1). The bouncing behavior of the two positive topological charges in TM-like band (charge bouncing) and the annihilation behavior of one positive and two negative topological charges in TE-like band (charge annihilation) (a2). The conservation law for the total topological charges predicts the behaviors of BICs with a system variation. Reprinted by permission from ref. 38, copyright 2014. b Strong coupling of modes in a dielectric resonator. Schematic of a dielectric cylindrical nanoresonator (b1) and calculated field profiles for the Mie-like mode and Fabry-Pérot-like mode (b2). Avoided resonance crossing (red circles) in the calculated graphs of the aspect ratio of the nanocylinder vs. frequency, for TM and TE-polarized incident waves (b3). c Far-field radiation patterns of TM1,1,1 mode in the nanocylinder in (b) for different aspect ratios. The middle image corresponds to the quasi-BIC. Reprinted by permission from ref. 41, copyright 2019.

Interestingly, the merging of BICs, following the conservation of total topological charges, can occur as a result of continuous changes in the structural parameters20. In the photonic-crystal slab structure of a square-lattice hole array (Fig. 3b), a symmetry-protected BIC is located at the center of the Brillouin zone with topological charge q = 1. Four accidental BICs with q = 1 are located in the Γ-M band, and the other four accidental BICs with q = –1 are located in the Γ-X band. The topological charges of the eight accidental BICs are controlled by the lattice constant. By varying the lattice constant, these accidental BICs move toward the Γ-point and merge into a BIC with q = 1, which is called a merging-BIC. The topological approach indicates that the Q factor of a merging-BIC is proportional to 1/k6, whereas the Q factor of an isolated BIC is proportional to 1/k2 in the reciprocal space. With this scaling rule for the Q factors, the merging-BIC is robust to the scattering loss and finite-size effect due to the suppression of the radiation leakage in disordered directions. Notably, this topological feature enables high-Q resonances in cavities with small footprints and fabrication imperfections.

Multipole analysis of BICs in subwavelength resonators

The optical waves are confined in a dielectric nanoresonator via both electric and magnetic Mie modes. Because of the negligible absorption of the dielectric material, nanoresonators only suffer from radiation loss40. However, it has been challenging to reduce the radiation loss and achieve well-defined light confinement in a subwavelength nanoresonator. The Mie modes in nanoresonators made of Si, Ge, and AlGaAs exhibit very low Q factors (Q ~ 5–10) in the visible and near-infrared wavelength regime37. On the other hand, the quasi-BIC mode or supercavity mode can overcome this limitation of subwavelength high-index dielectric nanoresonators35,36,37,41. In particular, a multipole analysis can provide not only an efficient design process for these high-Q cavities but also a clear explanation of the strong light confinement.

A multipole analysis of a subwavelength nanoresonator shows that strong mode coupling suppresses radiative losses and achieves high-Q resonances through destructive interference42,43,44. For example, a nanocylinder resonator supports two different types of resonant modes: a Mie-like mode (radial) and Fabry-Pérot-like mode (axial) (Fig. 4b)41. These can share the same radiation channel and form strong coupling. With a continuous change in the geometrical aspect ratio, strong coupling appears in the avoided crossing regime of the scattering cross-section spectrum. Then, Friedrich-Wintgen BICs are formed through the destructive interference of the radiation tails of the Mie-like mode and Fabry-Pérot-like mode. These high-Q supercavity modes were analyzed in a subwavelength nanocylinder structure (Fig. 4b). The Q factors reached up to ~250 for a GaP nanocylinder in the visible regime and ~2500 for a Ge nanocylinder in the near-infrared regime, although the Q factors were much lower in conventional subwavelength nanoresonators37.

Moreover, a multipole analysis illustrates the change in the dominant radiation channel in the supercavity mode (Fig. 4c)41. The radiation in nanocylinders can be decomposed into a series of multipole vector spherical harmonics. Electric dipole radiation is the dominant radiation channel for the TM1,1,1 mode, while the magnetic quadrupole is the minor one. With a change in the aspect ratio, the radiation from the electric dipole decreases rapidly, and the radiation contribution from the magnetic quadrupole becomes dominant in the supercavity mode. These changes in the dominant radiation are directly observed in the far-field radiation pattern (Fig. 4c). The negligible electric dipole radiation and dominant magnetic quadrupole radiation in the supercavity mode reveal that high-Q resonances are the result of the suppression of the dipolar radiation loss by the destructive interference of the Mie-like mode and Fabry-Pérot-like mode.

Passive BICs for enhanced nonlinearities

As an example of photonic applications, passive BICs have been used for enhanced nonlinear harmonic generation using a single dielectric nanoantenna and asymmetric metasurfaces. BICs have also been combined with monolayer TMDs, which exhibit enhanced harmonic intensities and large nonlinear exciton–polariton interactions. In addition, due to the high Q factor and strong light matter interaction, passive BICs can be used as a refractive index sensor.

Second-harmonic generation using quasi-BIC

In contrast to metallic structures, subwavelength high-index dielectric nanoantennas hosting a BIC mode exhibit low material absorption and low radiation loss, resulting in high-Q resonances35,37,41,45. In addition to the high Q factor, the volumetric distribution of the BIC mode inside the dielectric nanostructures enables the enhancement of the harmonic generation efficiency while relaxing the phase-matching condition22,46. Recently, it has been demonstrated that the quasi-BIC mode is a good platform for boosting the nonlinear effect22,46,47,48,49,50. Although the ideal BIC mode exhibits strong light–matter interaction with an infinite Q factor, it is difficult to inject sufficient light energy into a resonator because of the inaccessible radiation channel. In contrast, the quasi-BIC mode with a high-but-finite Q factor can be effectively excited by light illumination through the accessible radiation channel, enabling efficient frequency conversion and high-harmonic generation.

In 2020, Koshelev et al. demonstrated the quasi-BIC mode in an individual AlGaAs nanodisk at telecommunication wavelengths and exhibited a significant increase in the SHG efficiency (Fig. 5a)22. The AlGaAs nanodisk was placed on a three-layer substrate (SiO2/ITO/SiO2), which excited the Mie modes with axial and radial oscillations, showing a magnetic dipolar behavior. With the systematic variation of the nanodisk diameter, the strong coupling of the axial and radial Mie modes occurred, showing the characteristic avoided resonance crossing in the frequency curve. In this strong coupling regime, the hybrid modes of the axial or radial oscillations were observed as a result of constructive and destructive mode interference in the far field. In particular, the quasi-BIC mode, which was formed by destructive mode interference, exhibited the highest Q factor with the suppression of dipolar radiation. To further decrease the radiation leakage to the substrate and increase the Q factor of the quasi-BIC mode, a heavily doped ITO layer was introduced on top of the SiO2 substrate. This ITO layer behaved as a conductor when the designed quasi-BIC mode was excited at the telecommunication wavelength but as an insulator at the SHG wavelength. The spacer SiO2 layer between the nanodisk and ITO controlled the phase of the reflected light to maximize the Q factor of the quasi-BIC mode. In the experiment, the individual AlGaAs nanodisks exhibited a significantly increased Q factor of ~190 in the quasi-BIC regime.

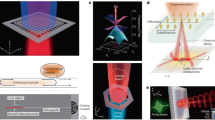

a Second-harmonic generation (SHG) using quasi-BICs. Schematic of the SHG in the AlGaAs nanodisk under azimuthally polarized beam excitation (a1). 3D map of second-harmonic intensity measured as a function of the pump wavelength and nanodisk diameter for an azimuthally polarized incident beam (a2). Measured second-harmonic intensity as a function of the nanodisk diameter at a 1570 nm pump wavelength for different pump polarizations (a3). Reprinted by permission from ref. 22, copyright 2020. b Nonlinear process in dielectric metasurfaces. Schematic of a metasurface comprising square-lattice dimers formed by two elliptical cylinders with a relative tilt of θ between their major axes (b1). Simulated (left) and measured (right) transmission spectra near the quasi-BIC resonance (upper) and SHG spectra (lower) with varying values for θ, from 30° to 5° (b2). Reprinted by permission from ref. 51, copyright 2020. c Si metasurface for third-harmonic generation (THG). THG from the quasi-BIC metasurface (c1), distribution of the carrier concentration in the metasurface unit cell (c2), scheme of the ultrafast self-action effect (c3), and THG spectra on the pump power (c4). Reprinted by permission from ref. 57, copyright 2021.

The enhanced SHG was measured based on the high-Q quasi-BIC mode in the subwavelength high-index dielectric nanoantenna (Fig. 5a). To increase the coupling strength between the incident light and quasi-BIC mode, an azimuthally polarized vector beam was used as the pump beam. Indeed, the quasi-BIC mode could be efficiently excited by this structured pump beam. The map of the SHG intensity was measured as a function of the pump wavelength and nanodisk diameter. The measurement clearly showed a significant increase in SHG efficiency in the quasi-BIC regime. In addition, SHG measurements using different pump beams with azimuthal, radial, and linear polarizations revealed that the azimuthally polarized pump beam generated the most efficient second-harmonic signal in the AlGaAs nanodisk. All these results strongly support the conclusion that the highest SHG efficiency originated from the excitation of the quasi-BIC mode. It was also noted that the measured SHG efficiency was two orders of magnitude higher than those of earlier works based on dipolar resonances49.

Nonlinear process in dielectric metasurfaces

Dielectric metasurfaces, the assembled dielectric nanoantennas in periodic arrays, are also attractive platforms for achieving enhanced SHG46,51,52,53,54,55,56. They provide an additional tuning knob for controlling the optical response by means of nanoantenna arrangements. In highly symmetric geometries, metasurfaces can host an ideal BIC mode. However, this mode is not detectable in the transmission spectra because of the complete decoupling of the BIC mode and incident light. By breaking the geometric symmetry, an ideal BIC can be converted into a quasi-BIC mode18. Recently, continuous-wave (CW) SHG has been demonstrated in asymmetric metasurfaces comprising subwavelength dielectric nanoantennas by exploiting the quasi-BIC mode (Fig. 5b)51. Anthur et al. designed asymmetric metasurfaces consisting of elliptic cylindrical-shaped GaP nanoantennas. These metasurfaces with asymmetric orientations of dimers showed a sharp resonant dip near the quasi-BIC mode, whereas the metasurfaces with perfect symmetric orientations showed no spectral features near the BIC mode. The Q factor of the BIC was controlled by tuning the level of the asymmetry, achieving a Q factor of ~2000 in the experiment. For the asymmetric metasurface hosting the BIC mode, an SHG efficiency of ~0.1% W–1 was measured using pulsed irradiation with an intensity of ~10 MW cm–2. In addition, an SHG efficiency of ~5 × 10–5% W–1 was obtained at the wavelength of the quasi-BIC mode for a CW pump intensity of 1 kW cm–2. Such high SHG efficiencies for reasonably low pump intensities were attributed to the quasi-BIC mode, which allowed the strong localization of light in the dimers with a high Q factor, as well as the coupling of the incident light to nanoantennas via an accessible radiation channel.

In addition to SHG, the quasi-BIC improves the efficiency of THG in Si metasufaces (Fig. 5c)50,52,57. With the asymmetric shape of the unit cell, the quasi-BIC can enhance the nonlinear effect due to the increase of the Q factor and light localization. In 2021, Sinev et al. demonstrated a rapid change in refractive index by multiphoton absorption in Si nanostructures. They constructed Si metasufaces with an asymmetric unit cell composed of two parallel bars of different widths. The metasurface was illuminated by a femtosecond laser with a pulse of 290 fs. The THG measurement showed that the resonant wavelength gradually shifted to a shorter wavelength with peak broadening as the pump power increased. The shift in peak wavelength indicates that the strong field ionization effect by multiphoton absorption leads to the self-action of laser pulse pumping58. In fact, this effect can be observed with small pump powers of a few mW in the Si metasurface. The modeling also showed that the free carrier concentration increased up to ~5 × 1018 cm–3 with a pump power of 10 mW, resulting in rapid changes of the refractive index and extinction coefficient. Consequently, the quasi-BIC mode provides a way to control the fast nonlinear dynamics with low power consumption, facilitating design optimization of nonlinear optical devices.

Nonlinear interactions with TMDs

The efficiency of the nonlinear optical process in monolayer TMDs is generally low because of their atomically thin geometric nature; however, the strong field enhancement by the quasi-BICs and ideal-BICs in metasurfaces can boost the nonlinear effect in TMDs48,59,60,61. The integration of monolayer TMD materials and BICs holds the promise of achieving higher efficiencies for nonlinear optical processes.

Figure 6a illustrates a representative example of the enhancement of the SHG in a monolayer TMD coupled to a spatially extended metasurface hosting a BIC mode48. A tungsten disulfide (WS2) monolayer was placed on top of a Si metasurface to implement the enhanced SHG signal based on the BIC resonance. The effect of the metasurface in the nonlinear process could be directly investigated by comparing the SHG intensities from the WS2 monolayers coupled with the Si metasurface and on top of the bulk Si film. Measurements showed that the SHG efficiency in WS2 with a Si metasurface was ~1140 times higher than that of WS2 on the bulk Si film. A power-to-power graph on the log10-log10 scale also showed a clear difference in the enhanced intensities for the two samples before the saturated SHG region.

a Enhanced second-harmonic generation (SHG) by hybridization of the asymmetric metasurface hosting the quasi-BIC and the monolayer WS2. Schematic (a1) and optical microscope image (a2) of the structure. Measured second-harmonic intensity spectra from WS2 on the metasurface (red) and bulk Si film (gray) (a3). Measured second-harmonic intensities vs. pump power for WS2 on the metasurface (red) and bulk Si film (gray) (a4). Reprinted by permission from ref. 48, copyright 2020. b Nonlinear process in monolayer MoSe2 on a 1D grating hosting a BIC mode. Schematic (b1) and optical microscope image (b2) of the structure. Angle-resolved reflectance spectra (b3) and corresponding Q factors (b4). Reprinted by permission from ref. 59, copyright 2020. c Hyperspectral imaging-based biomolecule detection. Recorded images with a CMOS camera create a hyperspectral data cube from high-resolution spectral information of individual pixels. Reprinted by permission from ref. 62, copyright 2019.

Moreover, resonant mode coupling between the excitonic emitters and the BIC resonator was demonstrated, and a large Rabi splitting was explored in the nonlinear light–matter interaction59. Figure 6b illustrates the nonlinear optical process in the exciton–polaritons in monolayer h-BN/MoSe2 on a 1D grating hosting a BIC mode. The fabricated 1D grating structure, consisting of 90-nm-thick Ta2O5 bars on a SiO2/Si substrate (1 μm/500 μm), opened the photonic band gap and formed a BIC mode near the exciton resonance. The reflectance and photoluminescent spectra of the 1D grating with the h-BN/MoSe2 layer showed a clear picture of the strong coupling and Rabi splitting. Measurements showed that the photonic band was split into upper and lower polariton branches (UPB and LPB, respectively) because of the strong coupling with neutral excitons in the MoSe2 centered at 1.65 eV. A Rabi splitting of 27 meV was observed owing to the nonlinear response of the exciton–polaritons. In addition, the Q factor was approximately 900 around the Γ point. Consequently, a hybrid system consisting of a monolayer semiconductor with BIC-based polaritonic excitations could effectively suppress radiation into the far field, narrow the spectrum, and enhance the nonlinear optical response.

Implementation of BIC modes for refractometric sensing

Extremely sharp resonances and strong light confinement of BIC modes are useful for ultrasensitive refractometric sensing applications. In contrast to their plasmonic platform counterparts, the high-Q dielectric metasurfaces with BIC modes offer low intrinsic absorption loss and compatibility with well-developed complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS). In particular, in visible and near-infrared wavelengths, the BIC modes are highly responsive to the local refractive index changes induced by biological entities such as biomolecules62,63,64,65 and membranes66 and even 2D materials with atom-level thickness62.

High-content data acquisition and processing platform using the high-Q BIC modes and hyperspectral imaging method have been successfully demonstrated62,63. In this technique, spatially resolved spectral information can be obtained without the usage of spectrometers or mechanical scanning. One example of biomolecule sensing is shown in Fig. 6c. The dielectric metasurface sensor array consists of pairs of tilted Si meta-units fabricated by CMOS-compatible process. A hyperspectral data cube was acquired using tunable supercontinuum laser source with a narrow bandwidth (~2 nm) and high spectral resolution (Δλ = 0.1 nm), which can be mapped spatially by tens of thousands of CMOS pixels. The resonance shifts induced by the biological entities were compared with reference maps acquired without any entity. In addition, the spectral resonance inherent in the asymmetric geometry of dielectric metasurfaces was optimized by scaling the geometric parameters and tilted angles to induce strong light confinement at the surrounding external volume of the nanostructure. The high-Q dielectric metasurface arrays not only enabled biometric analysis at very low molecular counts (~3 molecules per μm2), but also implemented a hyperspectral decoder that correlates the spectral information of each CMOS pixel with the spatial index.

Furthermore, the single imaging-based barcode sensing technique with the hyperspectral index decoder was utilized for efficient optical characterization of atomically thin 2D materials62. More recently, another sensing method based on toroidal dipole resonance at terahertz (THz) frequencies has been demonstrated, exploiting the non-destructivity and strong penetrability67,68. Therefore, these combinations of BIC-inspired nanophotonics and hyperspectral imaging methods can open a novel avenue for developing versatile and sensitive miniaturized spectroscopy and biosensing devices.

Active BICs for lasers

Active BICs present a new feedback mechanism for lasing. This section introduces demonstrations of directional lasing in BICs, ultrafast optical control of vortex beams, ultralow-threshold super-BIC lasers, and lasing from single dielectric nanoparticles.

Directional lasing in BICs

Wavelength-scale lasers provide promising applications because of the low power consumption required for optical cavities with increased Q factors69,70,71. Because cavity radiative losses are strongly suppressed in the regime of optical BICs, high-Q BIC cavities can be used to demonstrate efficient active nanophotonic devices. In particular, there have been several reports of unique cavity designs for controlling the optical properties of BIC lasers72,73,74,75.

In 2018, Ha et al. demonstrated a directional BIC laser using gallium arsenide nanopillar arrays19. GaAs nanopillars with a diameter of 100 nm and height of 250 nm supported only two dipole modes along the vertical and in-plane directions. In addition, the nanopillar array was designed to have two lattice periods: the lattice period was sub-diffractive (Px = 300 nm) in one direction and diffractive (Py = 540 nm) in the other direction. In this specific cavity design, the radiation channel allowed a BIC to be rendered into leakage resonance with a finite Q factor. Figure 7a shows a schematic of the radiation channel, which is the cross-point with ky = 0 in the emission plane.

a Directional lasing in nanoantenna arrays. Schematic of a GaAs nanopillar array on a fused silica substrate embedded in hydrogen silsesquioxane (HSQ) resist (a1). Measured back-focal plane image (a2) and directivity (a3) of the emission above the lasing threshold. Reprinted by permission from ref. 19, copyright 2018. b Ultrafast control of vortex beam. Schematic of a two-beam pumping experiment and the measured far-field emission patterns under both symmetric and asymmetric excitations (b1). Transition from a BIC microlaser to a linearly polarized laser (b2) and the reverse process (b3). Reprinted by permission from ref. 23, copyright 2020. c Ultralow-threshold super-BIC laser. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of a fabricated laser structure consisting of 40 × 40 unit cells (c1). Measured lasing wavelengths and far-field images of symmetry-protected BIC lasers (black dots; right inset) and accidental BIC lasers (red dots; left inset) as a function of the lattice constant (c2). The bottom inset shows the above-threshold spectrum of a super-BIC laser. Measured threshold values divided by the pump area (c3) and Q factors estimated by the peak wavelength and the linewidth at the transparent pumping condition (c4), as a function of the lattice constant. The orange line indicates the Q factor obtained using the resolution-limited linewidth of the spectrometer. Reprinted by permission from ref. 25, copyright 2021. d Lasing from single nanoparticles. SEM image (d1) and simulated near field of a quasi-BIC (d2) in a single GaAs nanocylinder. Evolution of the emission spectrum of the resonator at different pumping fluence values (d3). Reprinted by permission from ref. 24, copyright 2020.

This BIC structure was fabricated on a fused silica substrate embedded in a hydrogen silsesquioxane (HSQ) resist (spin-on glass), and optically pumped using a femtosecond laser at a low temperature of 77 K (Fig. 7a). The lasing action was successfully demonstrated, showing the unique features of the BIC. The lasing peak was observed at a wavelength of 825 nm, with a threshold of 14 μJ cm−2. The directionality of the laser was measured using back focal plane images of the emission. Notably, the directionality of the laser was compared above and below the threshold, and the lasing emission was observed at a specific angle corresponding to the leaky channel cross-point.

Ultrafast control of vortex beam

An optical vortex beam, which possesses a phase singularity with a spiral wavefront, has attracted attention because of its quantized orbital angular momentum (OAM)76,77,78,79,80,81. The optical properties of OAM states offer a viable solution for boosting the capacity of high-dimensional quantum information and data storage. To generate the OAM states, vortex microlasers were developed using spiral waveguides or micropillar chains with additional asymmetric scatterers78,79,80,82,83,84. However, the additional asymmetric scatterers significantly reduced the Q factor of the vortex laser. A vortex cavity with a high Q factor was implemented using the BIC mode85.

Recently, it has been shown that BIC modes with topologically protected charges can support a vortex beam with low energy consumption and high-speed optical modulations. In 2020, Huang et al. demonstrated perovskite-based vortex microlasers with a high Q factor and low lasing threshold, achieving all-optical switching at room temperature (Fig. 7b)23. A BIC structure consisting of a square array of circular holes with a radius of 105 nm and a lattice constant of 280 nm was fabricated using a 220 nm-thick lead bromide perovskite (MAPbBr3) film. In addition, the BIC structure was placed on a glass substrate and covered by polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) for vertical symmetry. The fabricated structures were optically pumped using a frequency-doubled Ti:sapphire laser at room temperature. The vortex properties of the emission were studied in the far-field angular distribution using the back focal plane imaging technique. Then, the vortex laser of the donut-shaped beam was successfully demonstrated. The central dark region due to the topological singularity at the beam axis was observed. The emission properties of the vortex laser could be controlled by changing the configuration of the pump laser. For example, under circular laser pumping, the symmetry was protected, and a donut-shaped beam was generated. Under elliptical laser pumping or the overlapping of two circular pump lasers, the symmetry was broken, and an emission profile with two lobes was observed. Notably, in the two-beam configuration of the pump laser, the time difference between the pump beams was used to switch the emission profile of the vortex laser from a donut shape to a two-lobe shape, with a switching time of 1–1.5 ps.

Ultralow-threshold super-BIC laser

Extended periodic structures consisting of hundreds of unit cells are suitable for the excitation of ideal BICs with Q factors of almost infinity. It was feasible to fabricate such a large cavity structure and measure its extremely high Q factor for passive photonic devices16,20,86. However, for active devices such as lasers, the use of a finite structure with a small footprint is unavoidable because of the limited spot size in optical or electrical pumping. Because the laser performance based on conventional BIC modes is limited by the finite cavity size, it is critical to maximize the Q factors of BIC modes in cavity structures with realistic sizes. Very recently, a new type of BIC mode has been proposed, which is called a super-BIC (a BIC in the supercavity region with an extremely high Q factor). This is a result of merging several BICs in the momentum space20,34,87. The super-BIC mode was observed by moving the topological charges closer to the Γ point in the momentum space, and a significantly increased Q factor was achieved even in a cavity of finite size.

A super-BIC laser was demonstrated by combining symmetry-protected and accidental BICs in the finite periodic photonic structure of a square lattice (Fig. 7c)25. First, the characteristics of the BIC modes were theoretically studied by varying the lattice constant of the photonic crystal slab. Symmetry-protected BIC and accidental BIC modes simultaneously appeared, and their wavelengths became closer as the lattice constant increased. After the two BIC modes merged, only a single mode was observed. Further theoretical analysis demonstrated that the radiative loss was strongly suppressed in the vicinity of the super-BIC regime, unlike other BIC modes. Numerical simulations were also performed to determine the super-BIC condition with the maximum radiative Q factor. Then, square-lattice photonic crystal structures with lattice constants ranging from 560 to 580 nm were fabricated on an InGaAsP slab with a thickness of 650 nm. Photoluminescence measurements were performed using a pulsed pump laser with a spot size of ~5.4 μm. One or two types of lasing modes were observed in the photonic crystal structures, depending on the lattice constant. The lasing peaks were categorized into two groups: symmetry-protected BIC (black dots) and accidental BIC (red dots), based on the measured far-field images and comparison with the simulation results. By extrapolating the wavelength of the accidental BIC mode, the merging point was estimated to be near the lattice constant of 574 nm.

For a more quantitative analysis of the super-BIC laser, the lasing threshold and Q factor were measured as a function of the lattice constant (Fig. 7c). The lasing threshold reached the minimum value in the super-BIC regime at a lattice constant of ≥574 nm. Interestingly, the experimental Q factor, which was estimated using the peak wavelength divided by the linewidth of the peak at the transparent pumping condition, showed the same behavior as the threshold. This indicated that the enhanced Q factor in the super-BIC regime was responsible for the significantly reduced threshold. The measured maximum Q factor was ~7300 as a result of the spectrometer-limited linewidth, although the actual value was much higher. In addition, it should be noted that the minimum threshold density was ~1.47 kW cm−2, which was approximately 50 to 10 million times lower than that of previously demonstrated BIC nanolasers. Therefore, in active nanophotonics, the super-BIC offers an efficient way to control the topological charges in the reciprocal space and dramatically reduce the radiative losses from the finite-size cavity.

Lasing from single nanoparticles

Lasing action from a single nanoparticle is attractive because of its extremely small physical size. However, only a limited number of lasers have been reported because of the small Q factor of the nanoparticles88,89,90. The quasi-BIC mode can be a viable solution to address this issue and achieve efficient lasing action in single nanoparticles. In 2020, Mylnikov et al. demonstrated lasing from a single-semiconductor nanocylinder hosting the quasi-BIC mode (Fig. 7d)24. Cylindrical nanoresonators were designed to create a strong interaction between the Mie and Fabry-Pérot modes. The Mie and Fabry-Pérot resonant modes are affected by the diameter and height of the nanocylinder, respectively. They interfere destructively from the outside, satisfying the supercavity condition of quasi-BIC. The avoided intersecting resonances due to the strong interaction between the two resonant modes were then observed in the scattering spectrum. A high Q factor of ~970 was obtained with the optimized geometric parameters of the nanocylinder.

A nanocylinder structure was fabricated using electron-beam lithography and a dry etching process after the GaAs film was transferred to a quartz substrate. The formation of the quasi-BIC mode at a wavelength of ~828 nm was confirmed through dark-field scattering measurements at cryogenic temperatures. The fabricated samples were optically pumped at a low temperature (77 K) using a femtosecond laser. The lasing peak was observed at a wavelength of 825 nm, exhibiting a threshold of 300 μJ cm–2. Second-order correlation measurements were also performed using the Hanbury-Brown-Twiss setup to further confirm the coherent nature of the laser emission. Furthermore, a statistical analysis of the lasing thresholds measured in nanocylinders of various diameters showed that the minimum threshold was achieved in the optimum diameter supporting the quasi-BIC mode.

Perspectives

Since the introduction of optical BICs with simple periodic systems in the 2000s, distinct principles for BICs have been developed to create a system that is completely decoupled from complex radiation channels. The accidental BICs at additional symmetry points, merging-BICs with merged multiple topological charges, and quasi-BICs in single nanoparticles discussed in this review show unique optical features that are attracting attention for a wide range of photonic systems. Focusing on the key metrics of the representative BIC principles, this review considered the recent progress in BICs and the development of their passive and active photonic applications. In the emerging research on passive dielectric single nanoresonators or metastructures, the significant enhancement of the optical field by BICs has been adjusted using nonlinear materials, enabling the efficient generation of nonlinear signals and applications such as imaging-based sensing. In addition, with the combination of active gain materials, BICs have shown remarkable potential for nanolasers with controlled optical properties such as directionality, high-speed modulation, beam shaping, and reduced energy consumption. Indeed, BICs were implemented in different platforms including a single or an array of nanostructure, and exhibited experimentally different Q values depending on the structure. These measured Q factors for various BICs were summarized in Table 1.

Many applications will be devised based on the unique properties of BICs. For example, the coupling of single-photon emitters to high-Q BIC cavities provides Purcell enhancement for practical and deterministic single-photon emitters91,92,93. A controlled beam profile and increased extraction efficiency for single photons have also been obtained. In addition, non-Hermitian photonic systems supported by BICs show distinct optical performances in terms of the radiation loss balanced by the gain contrast94,95,96. In steering, guiding, and localizing the modes of a distributed gain/loss environment, BICs may prevent energy dissipation and generate dynamically tunable optical modes. Furthermore, the topological features of BICs enable strong localization of light with a built-in immunity to disorder. Because a BIC cavity can maintain a high Q factor against external perturbations, electrically driven BIC lasers can be demonstrated with a low threshold. In fact, current injection into a wavelength-scale structure inevitably lowers the Q factor as a result of the formation of a current path. However, BIC cavities with topological features are expected to overcome this limitation. In addition, the topologically conserved BIC properties may benefit many vortex generator devices that suffer from low energy efficiency in transitions between OAM states97.

It is believed that this review suggests various routes for utilizing nanocavities to achieve exciting developments in the wide research fields of photonics, and BICs will play an important role in facilitating this ability in the future.

References

von Neumann, J. & Wigner, E. Über merkwürdige diskrete Eigenwerte. Phys. Z. 30, 465–467 (1929).

Friedrich, H. & Wintgen, D. Physical realization of bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. A 31, 3964–3966 (1985).

Marinica, D. C., Borisov, A. G. & Shabanov, S. V. Bound states in the continuum in photonics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 183902 (2008).

Bulgakov, E. N. & Sadreev, A. F. Bound states in the continuum in photonic waveguides inspired by defects. Phys. Rev. B 78, 075105 (2008).

Liu, V., Povinelli, M. & Fan, S. Resonance-enhanced optical forces between coupled photonic crystal slabs. Opt. Express 17, 21897 (2009).

Ndangali, R. F. & Shabanov, S. V. Electromagnetic bound states in the radiation continuum for periodic double arrays of subwavelength dielectric cylinders. J. Math. Phys. 51, 102901 (2010).

Suh, W., Yanik, M. F., Solgaard, O. & Fan, S. Displacement-sensitive photonic crystal structures based on guided resonance in photonic crystal slabs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 1999–2001 (2003).

Longhi, S. Transfer of light waves in optical waveguides via a continuum. Phys. Rev. A 78, 013815 (2008).

Longhi, S. Optical analogue of coherent population trapping via a continuum in optical waveguide arrays. J. Mod. Opt. 56, 729–737 (2009).

Dreisow, F. et al. Adiabatic transfer of light via a continuum in optical waveguides. Opt. Lett. 34, 2405–2407 (2009).

Lepetit, T., Akmansoy, E., Ganne, J. P. & Lourtioz, J. M. Resonance continuum coupling in high-permittivity dielectric metamaterials. Phys. Rev. B 82, 195307 (2010).

Lepetit, T. & Kanté, B. Controlling multipolar radiation with symmetries for electromagnetic bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. B 90, 241103 (2014).

Gentry, C. M. & Popović, M. A. Dark state lasers. Opt. Lett. 39, 4136–4139 (2014).

Hsu, C. W., Zhen, B., Stone, A. D., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Bound states in the continuum. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16048 (2016).

Plotnik, Y. et al. Experimental observation of optical bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 28–31 (2011).

Hsu, C. W. et al. Observation of trapped light within the radiation continuum. Nature 499, 188–191 (2013). The accidental BICs in a square-lattice photonic crystal appeared at the off-Γ wavevector in the reciprocal space.

Kodigala, A. et al. Lasing action from photonic bound states in continuum. Nature 541, 196–199 (2017). This paper reported the experimental demonstration of BIC laser based on the theoretical prediction of BIC modes.

Koshelev, K., Lepeshov, S., Liu, M., Bogdanov, A. & Kivshar, Y. Asymmetric metasurfaces with high-Q resonances governed by bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 193903 (2018). Theoretical study of asymmetric metasurfaces showed sharp high-Q resonances originated from a distortion of symmetry-protected BIC.

Ha, S. T. et al. Directional lasing in resonant semiconductor nanoantenna arrays. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 1042–1047 (2018).

Jin, J. et al. Topologically enabled ultrahigh-Q guided resonances robust to out-of-plane scattering. Nature 574, 501–504 (2019). Significantly increased Q factors were measured by merging multiple BICs in momentum space.

Kim, S., Kim, K. H. & Cahoon, J. F. Optical bound states in the continuum with nanowire geometric superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 187402 (2019).

Koshelev, K. et al. Subwavelength dielectric resonators for nonlinear nanophotonics. Science 367, 288–292 (2020). High-Q quasi-BIC modes in an individual subwavelength dielectric resonator increased the nonlinear efficiency of second-harmonic generation.

Huang, C. et al. Ultrafast control of vortex microlasers. Science 367, 1018–1021 (2020).

Mylnikov, V. et al. Lasing action in single subwavelength particles supporting supercavity modes. ACS Nano 14, 7338–7346 (2020).

Hwang, M. S. et al. Ultralow-threshold laser using super-bound states in the continuum. Nat. Commun. 12, 4135 (2021). A supercavity mode created by merging symmetry-protected and accidental BICs realized a low-threshold laser based on a finite-size cavity.

Azzam, S. I. & Kildishev, A. V. Photonic bound states in the continuum: from basics to applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9, 16–24 (2021).

Koshelev, K., Favraud, G., Bogdanov, A., Kivshar, Y. & Fratalocchi, A. Nonradiating photonics with resonant dielectric nanostructures. Nanophotonics 8, 725–745 (2019).

Hwang, M. S. et al. Recent advances in nanocavities and their applications. Chem. Commun. 57, 4875–4885 (2021).

Hwang, M. S., Kim, H. R., Jeong, K. Y., Park, H. G. & Kivshar, Y. Novel non-plasmonic nanolasers empowered by topology and interference effects. Nanophotonics 10, 3599–3611 (2021).

Koshelev, K., Bogdanov, A. & Kivshar, Y. Engineering with bound states in the continuum. Opt. Photonics N. 31, 38 (2020).

Kim, S. et al. Mie-coupled bound guided states in nanowire geometric superlattices. Nat. Commun. 9, 2781 (2018).

Hirose, K. et al. Watt-class high-power, high-beam-quality photonic-crystal lasers. Nat. Photonics 8, 406–411 (2014).

Yang, Y., Peng, C., Liang, Y., Li, Z. & Noda, S. Analytical perspective for bound states in the continuum in photonic crystal slabs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 037401 (2014).

Koshelev, K. & Kivshar, Y. Light trapping gets a boost. Nature 574, 491 (2019).

Rybin, M. V. et al. High-Q supercavity modes in subwavelength dielectric resonators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 243901 (2017).

Rybin, M. & Kivshar, Y. Supercavity lasing. Nature 541, 164–165 (2017).

Odit, M. et al. Observation of supercavity modes in subwavelength dielectric resonators. Adv. Mater. 33, 2003804 (2021).

Zhen, B., Hsu, C. W., Lu, L., Stone, A. D. & Soljačić, M. Topological nature of optical bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 257401 (2014). This paper explained the topological nature of optical BICs from polarization vector fields.

Bulgakov, E. N. & Maksimov, D. N. Bound states in the continuum and polarization singularities in periodic array of dielectric rods. Phys. Rev. A 96, 063833 (2017).

Kuznetsov, A. I., Miroshnichenko, A. E., Brongersma, M. L., Kivshar, Y. S. & Luk’yanchuk, B. Optically resonant dielectric nanostructures. Science 354, aag2472 (2016).

Bogdanov, A. A. et al. Bound states in the continuum and Fano resonances in the strong mode coupling regime. Adv. Photon 1, 016001 (2019).

Sadrieva, Z., Frizyuk, K., Petrov, M., Kivshar, Y. & Bogdanov, A. Multipolar origin of bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. B 100, 115303 (2019).

Liu, T., Xu, R., Yu, P., Wang, Z. & Takahara, J. Multipole and multimode engineering in Mie resonance-based metastructures. Nanophotonics 9, 1115–1137 (2020).

Chen, W., Chen, Y. & Liu, W. Multipolar conversion induced subwavelength high-Q Kerker supermodes with unidirectional radiations. Laser Photon. Rev. 13, 1900067 (2019).

Han, S. et al. All-dielectric active terahertz photonics driven by bound states in the continuum. Adv. Mater. 31, 1901921 (2019).

Carletti, L., Koshelev, K., De Angelis, C. & Kivshar, Y. Giant nonlinear response at the nanoscale driven by bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 033903 (2018).

Koshelev, K. & Kivshar, Y. Dielectric resonant metaphotonics. ACS Photonics 8, 102–112 (2021).

Bernhardt, N. et al. Quasi-BIC resonant enhancement of second-harmonic generation in WS2 monolayers. Nano Lett. 20, 5309–5314 (2020).

Kruk, S. S. et al. Nonlinear optical magnetism revealed by second-harmonic generation in nanoantennas. Nano Lett. 17, 3914–3918 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. High-Q quasibound states in the continuum for nonlinear metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 253901 (2019).

Anthur, A. P. et al. Continuous wave second harmonic generation enabled by quasi-bound-states in the continuum on gallium phosphide metasurfaces. Nano Lett. 20, 8745–8751 (2020). Second-harmonic generation process in a dielectric metasurface was enhanced by two asymmetric cylinders with quasi-BIC resonances.

Koshelev, K. et al. Nonlinear metasurfaces governed by bound states in the continuum. ACS Photonics 6, 1639–1644 (2019).

Sain, B., Meier, C. & Zentgraf, T. Nonlinear optics in all-dielectric nanoantennas and metasurfaces: a review. Adv. Photon 1, 024002 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Broadband metasurfaces with simultaneous control of phase and amplitude. Adv. Mater. 26, 5031–5036 (2014).

Zheng, G. et al. Metasurface holograms reaching 80% efficiency. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 308–312 (2015).

Li, G., Zhang, S. & Zentgraf, T. Nonlinear photonic metasurfaces. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17010 (2017).

Sinev, I. S. et al. Observation of ultrafast self-action effects in quasi-BIC resonant metasurfaces. Nano Lett. 21, 8848–8855 (2021).

Shcherbakov, M. R. et al. Photon acceleration and tunable broadband harmonics generation in nonlinear time-dependent metasurfaces. Nat. Commun. 10, 1345 (2019).

Kravtsov, V. et al. Nonlinear polaritons in a monolayer semiconductor coupled to optical bound states in the continuum. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 56 (2020).

Koshelev, K. L., Sychev, S. K., Sadrieva, Z. F., Bogdanov, A. A. & Iorsh, I. V. Strong coupling between excitons in transition metal dichalcogenides and optical bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. B 98, 161113(R) (2018).

Wang, T. & Zhang, S. Large enhancement of second harmonic generation from transition-metal dichalcogenide monolayer on grating near bound states in the continuum. Opt. Express 26, 322–337 (2018).

Yesilkoy, F. et al. Ultrasensitive hyperspectral imaging and biodetection enabled by dielectric metasurfaces. Nat. Photonics 13, 390–396 (2019). Dielectric metasurfaces supporting high-Q BIC resonances and hyperspectral imaging were combined to develop an ultrasensitive label-free biosensing platform.

Tittl, A. et al. Imaging-based molecular barcoding with pixelated dielectric metasurfaces. Science 360, 1105–1109 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. All-dielectric crescent metasurface sensor driven by bound states in the continuum. Adv. Func. Mater. 31, 2104652 (2021).

Zito, G. et al. Label-free DNA biosensing by topological light confinement. Nanophotonics 10, 4279–4287 (2021).

Romano, S. et al. Ultrasensitive surface refractive index imaging based on quasi-bound states in the continuum. ACS Nano 14, 15417–15427 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Toroidal dipole bound states in the continuum metasurfaces for terahertz nanofilm sensing. Opt. Express 28, 17102 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Ultrasensitive terahertz sensing with high-Q toroidal dipole resonance governed by bound states in the continuum in all-dielectric metasurface. Nanophotonics 10, 1295–1307 (2021).

Noda, S., Yokoyama, M., Imada, M., Chutinan, A. & Mochizuki, M. Polarization mode control of two-dimensional photonic crystal laser by unit cell structure design. Science 293, 1123–1125 (2001).

Jeong, K. Y. et al. Electrically driven nanobeam laser. Nat. Commun. 4, 2822 (2013).

Jeong, K. Y. et al. Recent progress in nanolaser technology. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001996 (2020).

Muhammad, N., Chen, Y., Qiu, C. W. & Wang, G. P. Optical bound states in continuum in MoS2-based metasurface for directional light emission. Nano Lett. 21, 967–972 (2021).

Azzam, S. I. et al. Single and multi-mode directional lasing from arrays of dielectric nanoresonators. Laser Photonics Rev. 15, 2000411 (2021).

Wu, M. et al. Room-temperature lasing in colloidal nanoplatelets via Mie-resonant bound states in the continuum. Nano Lett. 20, 6005–6011 (2020).

Bi, W. et al. Low-threshold and controllable nanolaser based on quasi-BIC supported by an all-dielectric eccentric nanoring structure. Opt. Express 29, 12634 (2021).

Qui, C. W. & Yang, Y. Vortex generation reaches a new plateau. Science 357, 645 (2017).

Özdemir, Ş. K., Rotter, S., Nori, F. & Yang, L. Parity–time symmetry and exceptional points in photonics. Nat. Mater. 18, 783–798 (2019).

Miao, P. et al. Orbital angular momentum microlaser. Science 353, 464–467 (2016).

Stellinga, D. et al. An organic vortex laser. ACS Nano. 12, 2389–2394 (2018).

Zambon, N. C. et al. Optically controlling the emission chirality of microlasers. Nat. Photon 13, 283–288 (2019).

Feldmann, J., Youngblood, N., Wright, C. D., Bhaskaran, H. & Pernice, W. H. P. All-optical spiking neurosynaptic networks with self-learning capabilities. Nature 569, 208–214 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Tunable topological charge vortex microlaser. Science 368, 760–763 (2020).

Chen, B. et al. Bright solid-state sources for single photons with orbital angular momentum. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 302–307 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. An InP-based vortex beam emitter with monolithically integrated laser. Nat. Commun. 9, 2652 (2018).

Wang, B. et al. Generating optical vortex beams by momentum-space polarization vortices centred at bound states in the continuum. Nat. Photonics 14, 623–628 (2020).

Yin, X., Jin, J., Soljačić, M., Peng, C. & Zhen, B. Observation of topologically enabled unidirectional guided resonances. Nature 580, 467–471 (2020).

Chen, Z. et al. Science Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2021.10.020 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Visible Submicron microdisk lasers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 111119 (2007).

Song, Q., Cao, H., Ho, S. T. & Solomon, G. S. Near-IR subwavelength microdisk lasers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 061109 (2009).

Tiguntseva, E. Y. et al. Single-particle Mie-resonant all-dielectric nanolasers. arXiv:1905.08646. https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.08646.

Lodahl, P., Mahmoodian, S. & Stobbe, S. Interfacing single photons and single quantum dots with photonic nanostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 347–400 (2015).

Peyskens, F., Chakraborty, C., Muneeb, M., Van Thourhout, D. & Englund, D. Integration of single photon emitters in 2D layered materials with a silicon nitride photonic chip. Nat. Commun. 10, 4435 (2019).

So, J. P. et al. Polarization control of deterministic single-photon emitters in monolayer WSe2. Nano Lett. 21, 1546–1554 (2021).

Kim, K. H. et al. Direct observation of exceptional points in coupled photonic-crystal lasers with asymmetric optical gains. Nat. Commun. 7, 13893 (2016).

Weimann, S. et al. Topologically protected bound states in photonic parity–time-symmetric crystals. Nat. Mater. 16, 433–438 (2017).

Song, Q. et al. Coexistence of a new type of bound state in the continuum and a lasing threshold mode induced by PT symmetry. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc1160 (2020).

Ni, J. et al. Multidimensional phase singularities in nanophotonics. Science 374, eabj0039 (2021).

Acknowledgements

H.-G.P. acknowledges the support from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (2021R1A2C3006781 and 2020R1A4A2002828) and the Institute for Information & Communications Technology Promotion (IITP) grant (2020-0-00841). K.-H.K. acknowledges the support from the NRF grant (NRF-2019R1C1C1006681). M.-S.H. acknowledges the support from the NRF grant (NRF-2020R1I1A1A01074347). K.-Y.J. acknowledges the support from the NRF grant (NRF-2020R1I1A1A01066655).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.-S.H., K.-Y.J., J.-P.S., K.-H.K., and H.-G.P. designed and wrote this review.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, MS., Jeong, KY., So, JP. et al. Nanophotonic nonlinear and laser devices exploiting bound states in the continuum. Commun Phys 5, 106 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-00884-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-00884-5

This article is cited by

-

Exciton polariton condensation from bound states in the continuum at room temperature

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Applications of bound states in the continuum in photonics

Nature Reviews Physics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.