Abstract

Stochastic fluctuations of the neutron population within a nuclear reactor are typically prevented by operating the core at a sufficient power, since a deterministic (i.e., exactly predictable) behavior of the neutron population is required by automatic safety systems to detect unwanted power excursions. In order to characterize the reactor operating conditions at which the fluctuations vanish, an experiment was designed and took place in 2017 at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Reactor Critical Facility. This experiment however revealed persisting fluctuations and striking patchy spatial patterns in neutron spatial distributions. Here we report these experimental findings, interpret them by a stochastic modeling based on branching random walks, and extend them using a “numerical twin” of the reactor core. Consequences on nuclear safety will be discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding space–time fluctuations of the neutron population is key to nuclear safety, especially in connection with reactor control at startup and shutdown. Operating the reactor in the deterministic (i.e. exactly predictable) regime ensures that power variations can be related to a change of the state of the reactor that requires proper human/automatic action. For instance, a sudden rise in reactor power demands a reactor tripping procedure (initiated by the reactor automatic protection system). The persistence of stochastic effects, potentially screening such a state of the reactor, shall therefore be avoided. In this respect, the appearance of fission-induced correlations in nuclear systems has been extensively investigated1,2 and a large attention has been devoted to the development of simulation capabilities relying on high-performance computing and aiming at characterizing the fluctuations and correlations3,4,5,6. Some of the numerical simulations reported strong non-Poissonian patterns affecting neutron spatial distributions in decoupled nuclear systems, where the system size is larger than the typical length scale travelled by the neutrons. In particular, the occurrence of a spontaneous clustering of the neutron population has drawn much attention in recent years7,8,9,10,11,12,13 and questions were raised as to whether this phenomenon was a simulation artifact or if it could be experimentally detected. It is known that a collection of independent particles that move, reproduce, and die may undergo wild fluctuations at the local and global scales inducing a characteristic patchiness in the spatial distribution of the individuals observed in the context of life sciences, including the spread of epidemics14,15,16, the growth of bacteria on Petri dishes17,18, the dynamics of ecological communities19,20, and the mutation propagation of genes21,22. The central ingredient behind the appearance of clustering is the asymmetry between death occurring everywhere and birth being only possible close to a parent particle; particle diffusion has a smoothing effect on the wild spatial patterns induced by the parent–child correlations23. Particle clustering is the signature of strong deviations from the average behavior of such stochastic systems and has been shown to be enhanced in low-dimension (d = 1 or d = 2), especially when the population is fairly diluted: a deterministic description would be thus meaningless, since the typical size of the fluctuations might be of the same order of magnitude as the average particle density24,25. The evolution of the neutron population in a nuclear reactor being also subject to random displacements (diffusion), births (fission events on heavy nuclei leading to secondary neutrons), and deaths (capture events on nuclei leading to the disappearance of the colliding neutrons), it has been therefore suggested that clustering might occur experimentally within a nuclear reactors operated at low power, i.e., low neutron density7,8. This motivated an international collaboration gathering Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), the French Institute for Radiological Protection and Nuclear Safety and the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission, with three objectives: designing ad hoc experiments and dedicated detectors to extract information on neutron fluctuations at low reactor power—below the detectors saturation threshold; building a numerical twin of the operating reactor based on Monte Carlo simulation so as to support experimental results and to fill the gaps of experimental measurements while extrapolating them at higher power; and interpreting the obtained results in the framework of stochastic branching processes. The experiments took place at the Reactor Critical Facility (RCF)26 of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute over a week in August 2017 and were followed by the analysis of measured data using the MORET6 Monte Carlo neutron transport code (MORET6 is based on MORET527) and features additional analog neutron transport capabilities. In the following we will report our main findings and we will show in particular that fluctuations can persist up to unexpectedly high reactor powers and cause a “blinking” behavior of the reactor. Strong spatial correlations affecting neutron distributions will be reported and characterized. A stochastic modeling using branching random walk techniques will underline the key role played by spontaneous fissions to understand both qualitatively and quantitatively the neutron clustering phenomena detected at the RCF.

Results

Analysis of the average behavior of the neutron population

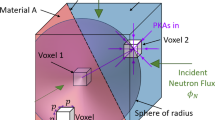

The neutron detection system installed at the RCF is described Fig. 1: it featured in-core and ex-core 3He detectors used to reconstruct the neutron spatial distribution given in Fig. 2, obtained from a 10 min run at a power P = 0.66 mW. The simulated counting rates obtained using MORET6, rescaled in order to describe the sought reactor power (see “Methods” section), show a 2-σ agreement with the experimental data, for both in-core and ex-core detectors. The inner detectors show a flat central power distribution with sharp decays near the boundaries. This spatial profile can be understood at the light of a simplified, yet representative, stochastic model where the key mechanisms of diffusion, fissions, captures, and spatial leakages out of the system are retained. At low power, intrinsic sources induced by the spontaneous fissions on 238U (which emits 1 n/s/g, i.e., more than 103 times higher than neutrons emitted by (α, n) reactions on oxygen and more than 104 times higher than neutrons emitted by spontaneous fissions on 235U) must be also taken into account in the model by adding a constant neutron production term. Assuming for the sake of simplicity Brownian diffusion for the neutron displacements, the evolution equations for the moments of the neutron population n(r, t) at location r and time t can be explicitly derived as done in Supplementary Notes 1–3. The ensemble-averaged neutron density c(r, t) = 〈n(r, t)〉 satisfies

where D is the neutron diffusion coefficient, ρ is the reactivity (i.e. the normalized neutron production rate, by fissions, minus the normalized capture rate, which is also noted ρ = ρ∞ when the medium is spatially infinite and leakages are not taken into account), Λ is the mean generation time (i.e. the average time between two generations), \({\lambda }_{\,\text{SF}}^{\text{v}\,}\) is the volumic spontaneous fission rate, and \(\overline{{\nu }_{\text{SF}}}\) is the mean number of neutrons produced per spontaneous fission. Equation (1) has the form of a standard reaction-diffusion equation. It is convenient to investigate the system behavior along the vertical (z) axis, i.e., the coordinate explored by the experimental detectors in RCF: this is achieved by projecting the solution c(r, t) along z, to yield c(z, t). Stationary solutions

can be determined assuming a negative reactivity and leakage boundary conditions at both ends z = ± L of the core, where we have introduced the rescaled length \({L}^{* }=\sqrt{\frac{{{\Lambda }}D}{-\rho }}\) and the asymptotic neutron concentration \({c}_{\infty }=\frac{{\lambda }_{\text{SF}}\ \overline{{\nu }_{\text{SF}}}{{\Lambda }}}{-\rho }\). The asymptotic neutron concentration being proportional to the reactor power P, the reactivity is related to the ratio between the intrinsic sources \(S={\lambda }_{\text{SF}}\ \overline{{\nu }_{\text{SF}}}\) and the system power P through ρ = −S/P: ρ therefore ranges from ρ = −1, when sources are not amplified by multiplication in the core, up to ρ = 0, when P diverges due to the amplification of the constant production of neutrons by intrinsic sources. In the absence of sources, Eq. (1) admits the stationary solution \(c(z)=A\cos \left(\right.\frac{\pi z}{2L}\left)\right.\) where A is an arbitrary amplitude, provided that ρ > 0 satisfies the condition \(L=\frac{\pi }{2}\sqrt{\frac{{{\Lambda }}D}{\rho }}\). The transition between these qualitatively different asymptotic average neutron concentrations occurs at ρ = 0, which defines the criticality condition for the reactor. In the case of the RCF reactor, above about P = 1 W, the average neutron population exhibits the cosine shape, while below about P = 10 mW it is driven by spontaneous fissions and the spatial shape obeys Eq. (2).

a Top view of the RCF nuclear reactor, with two neutron multiplicity 3He array detectors (NoMAD) in their water-proof cases on the left side. The red scale bar is 34 cm long. b The NoMAD detectors are made of 15 3He tubes (left: picture with a 38 cm white scale bar, right: MORET6 (Monte Carlo neutron transport code) modeling of a NoMAD detector out of its case, where the 3He tubes appear in green). The positioning of these detectors just next to the reactor allows to reconstruct the axial power distribution up to reactor power close to 10 mW, avoiding dead time and saturation effects. c MORET6 modeling of one of the four identical 3He tubes positioned within a “detector” pincell placed in the center of the reactor so as to reconstruct the axial power distribution directly within the reactor, up to a power of 2 mW. d, e Side view and top view, respectively, of the reactor and the detectors, modeled using MORET6. On panel d, the vertical fuel rods appear in orange and the structural materials and the control rods appear in gray. During operation, the reactor is immersed in water (which appears in blue, in panel e).

a Side view of the MORET6 model of the RCF reactor equipped with the four central 3He tubes and with the two lateral NoMAD detectors. b, c Axial fluxes measured at P = 0.79 mW (blue squares) and simulated at P = 0.79 mW (red circles) using the NoMAD detectors. d Axial fluxes measured at P = 0.79 mW (blue squares) and simulated at P = 0.66 mW (red circles) using the 3He inner detectors. Statistical error bars where evaluated using bootstrap both for simulated and experimental data. Systematic error bars on the positioning in z of 3He tubes within the NoMAD detectors have been evaluated to be approximately of 1 cm, and have been reported both on simulated and experimental data. All error bars lie within the squares and circles symbols. Both axial "cosine" shapes are within 2-σ agreement for the inner 3He detectors, while a systematic underestimation of the simulated flux appears on the top NoMAD detector. This might be attributed to the positioning of the detector during the experiment, which might have been slightly displaced during the reactor immersion.

Fluctuations and neutron blinking

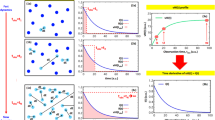

The 2017 RCF experiments featured a dedicated run targeting the observation of the neutron fluctuations as a function of time. The reactor was placed in a close-to-critical state and fluctuations were monitored without any human intervention to stabilize the core during time windows ranging from 30 min to 2 h. Figure 3a presents in blue the power fluctuations measured by the LP detectors of the 9 mW run with a time-gate width set to 1 ms during the analysis. A zoom on this power when the signal reaches stationarity is given (Fig. 3b) and compared to simulation results obtained by MORET6 corresponding to a power of 0.8 mW (Fig. 3c). The reactor power fluctuations extracted from the simulations are also presented on consecutive 3D views (Fig. 3d). Both in simulated and experimental data, asymptotically the signal attains a stationary regime with a similar noise level. This is mirrored in the variance-to-mean ratio of both simulated and measured signals being also bounded and independent of the reactor power, as shown in Fig. 4a. These observations are strikingly different from those of the so-called “critical catastrophe” model proposed by Williams1, which predicts an unbounded growth in time of the fluctuations. In this model, that neglects spontaneous fission sources, an exactly critical reactor would have the following variance-to-mean ratio (see developments exposed in Supplementary Note 1)

where λF is the fission rate, \(\overline{{\nu }_{\text{F}}}\) is the average number of neutrons produced per fission, and n0 is the initial number of neutrons. As noticed by Williams1, the variance-to-mean (V/M) ratio of the neutron population in the core would diverge linearly with time and a critical reactor would undergo a “critical catastrophe”, namely unbounded power fluctuations (eventually leading to shutdown). In practice, feedback mechanisms such as the temperature effect at high power or operator-induced control rod movements at low power, supposedly quench the critical catastrophe1,9,28.

a “Critical catastrophe” run at 9 mW during the Reactor Critical Facility (RCF) experiments (blue), with a zoom on the beginning of its stationary part (b) compared to MORET6 simulated data (red) at 0.8 mW (c). The time-gate width used by the offline analysis was set to 1 ms. After a transient period (light blue) where the system reaches equilibrium, both experimental and numerical signals stabilize as well as their fluctuations. While the power levels of the RCF data signal and the MORET6 simulated data are different, the stochastic neutron noises (variance-to-mean) are approximately the same, as foreseen by the stochastic modeling taking into account spontaneous fissions and delayed neutrons. The “critical catastrophe” predicted by Williams1 is prevented by the mechanism described in Eq. (4): the fluctuations are contained by the under-critical behavior of the core related to spontaneous fission sources. d Numerical simulation of the power fluctuations, using a fully “analog” simulation of the entire setup operated at 1.2 mW (reactor equipped with detectors and simulated with realistic statistics of neutrons). These simulations have been performed during 104 processors.day on Intel® Xeon® E5-2680 cores. Whenever analyzed with 1 ms time gate, the core exhibits a “blinking power” behavior, as also shown in Supplementary Video 1.

The simulation results (red circles) are compared to the Reactor Critical Facility (RCF) experimental data (blue squares) and fitted by the stochastic model (black lines) for a small time gate (a Δt = 1 ms) and for a large time gate (b Δt = 1 s). In this last plot, only simulation results are presented as experimental acquisition time for such time gates were out of reach. For small time gates the noise saturates while, for large time gates, it grows unbounded following a P2 law (up to the recovering of the “critical catastrophe” regime) due to vanishing intrinsic sources. Statistical error on variance-to-mean ratio are given by a bootstrap method, both for simulated and experimental data. Relative errors on the power estimation of experimental data were overestimated at 10%, using the detectors calibration. The simulated data of panel b do not have error bars on the variance-to-mean ratio due to insufficient statistics for such large time gates.

The bounded behavior of the variance-to-mean ratio observed during the experiments therefore calls for a different modeling. In the random walk model of the RCF introduced above, spontaneous fissions play a central role since an exactly critical reactor having constant neutron sources might behave as an under-critical system from the point of view of the induced fissions—the fission chain. Indeed, on the one hand, according to this model the presence of spontaneous fissions prevents the number of neutrons (and thus the power) from becoming extinct. On the other hand, the reactivity ρ must be negative in order for the neutron population to reach an asymptotic level. Neglecting the effects of spatial boundaries and assuming that the mean number of neutrons generated per fission and spontaneous fission are similar (\(\overline{{\nu }_{\text{SF}}}\approx \overline{{\nu }_{\text{F}}}\)), the time-asymptotic variance-to-mean ratio predicted by the model (whose demonstration is given in Supplementary Note 1) is

This formula can be understood by remarking that the negative reactivity also prevents the neutron population from stepping too far beyond its average value. The random walk n(t) therefore "bounces" between the limits imposed by the intrinsic sources and by the asymptotic population. For a strongly sub-critical reactor driven by intrinsic sources (ρ ≈ −1), the deviation of the variance-to-mean ratio with respect to the Poisson behavior is almost doubled. The mean number of pairs for spontaneous or induced fission on 235U or 239Pu is close to unity. A constant V/M ratio is associated to \(1/\sqrt{P}\) vanishing fluctuations \({\sigma }_{n}/\langle {n}_{\infty }\rangle =\sqrt{{V}_{n}}/\langle {n}_{\infty }\rangle\) since 〈n∞〉 ∝ P. On the contrary, when the core is close to criticality (as in the RCF), the asymptotic variance-to-mean ratio scales as P since Vn/〈n∞〉 ∝ ∣ρ∣−1 ∝ P/S, which suggests a power-dependent noise but power-independent fluctuations σn/〈n∞〉 ∝ S−1/2. Therefore, while the bounded behavior in time of the noise observed at the RCF naturally emerges from this model, it fails to predict that the noise does not appear to depend on the power for 1 ms time-gate width. Also, in view of the coherence between the Monte Carlo simulations and the experimental results, we have also used MORET6 to access information not directly available from the detectors, which led to another surprising observation: increasing the time-gate width Δt from 1 ms to 1 s drastically changes the behavior of the stochastic neutron noise versus power, which follows a square law (see Fig. 4b). Furthermore, Fig. 3d reports the direct observation of the neutron population observed on larger time scales but still with a time-gate width set at 1 ms. As shown in this plot, most of the time, the power is close to zero, and from time to time neutron bursts occur in the reactor, triggered by fission chains originating from spontaneous fission events (see also Supplementary Video 1). The reactor seems to present a characteristic “blinking” behavior: the use of small time gates allows to observe the neutron chains triggered by spontaneous fissions individually. To better grasp the effect of time gates width on the behavior of the reactor, the stochastic modeling cannot solely rely on Eq. (4), which has been derived by neglecting the contribution of delayed neutrons. While prompt neutrons are emitted almost instantaneously by induced or spontaneous fissions, delayed neutrons are sometimes produced when weak forces are used by induced or spontaneous fission products (called precursors) to gain stability. Inasmuch as the beta decay occurs on much longer time scales than the emission of prompt neutrons (ranging from 1 ms up to few minutes), and even if delayed neutrons represent only a small fraction β of fission neutrons (the delayed neutron fraction β is roughly 0.7% for thermal fissions on 235U), both the kinetic parameters of the reactor (e.g. power doubling period) and the time fluctuations of the neutron population are subtly affected. Also, the description of a time detector was included in the modeling (representing the real sensitive 3He detectors which integrate neutron capture events within time bins) so as to count the asymptotic number of detected neutrons 〈z∞〉 = ϵλF n∞Δt within a given time-gate Δt (ϵ is the efficiency of the detector setup and n∞ is the asymptotic number of neutrons in the reactor). Under rather mild assumptions detailed in the Supplementary Note 2, considering small time-gate width (and hence \(t\approx {({\alpha }_{\text{p}})}^{-1}\) where \({\alpha }_{\text{p}}=\frac{\beta -\rho }{{{\Lambda }}}\)) leads to a noise that does not depend on the reactor power, as reported by Fig. 4a. If one is interested in larger time-gate width characterized by \(t\gg {({\alpha }_{\text{d}})}^{-1}\) where \({\alpha }_{\text{d}}=\frac{-{\lambda }_{\text{D}}\ \rho }{\beta -\rho }\) (λD is the beta decay rate leading to the appearance of delayed neutrons) and introducing the mean number of prompt neutrons produced by fission νn, the mean number of neutrons emitted by the decaying precursor \(\overline{{\nu }_{\text{m}}}\), and the Diven factor \({D}_{\nu }=\frac{\overline{{\nu }_{\text{n}}({\nu }_{\text{n}}-1)}}{{\overline{{\nu }_{\text{n}}}}^{2}}\), the time-asymptotic variance-to-mean ratio of the number of detected neutrons z∞ takes the form

This equation is a specialization of the general formulation found in refs. 29,30 and the stochasticity induced by the spontaneous fission source is found to be taken into account via the simple multiplicative term (1 − ρ). Since the average power of the reactor is directly proportional to the asymptotic number of neutrons P ∝ n∞ ∝ ∣ρ∣−1, it follows that the variance-to-mean ratio follows Varz(Δt)/〈zΔt〉 ∝ P2 and, given that the average number of detected neutrons is proportional to P through 〈z∞〉 = ϵλF n∞Δt, the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean diverges when the core power is increased according to \({\sigma }_{z}({{\Delta }}t)/\langle {z}_{{{\Delta }}t}\rangle \propto \sqrt{P/{{\Delta }}t}\). This suggests that, even though intrinsic sources prevent the “critical catastrophe”, the time scale of emission of the delayed neutrons might lead to a recovery of the “critical catastrophe” regime since the system has enough time to enhance the neutron stochastic noise which grows unbounded with power. Figure 4b corroborates precisely the square divergence of the noise as a function of power (and hence fluctuations diverging as square root of the power). This, however, can only occur for time gates width eventually not accessible to experiments. Indeed, since the numerical values of β and λD are such that β/λD ≈ 1 s−1, for close-to-critical systems we have \({\alpha }_{\,\text{d}\,}^{-1}\approx | \rho {| }^{-1}\approx P/S\) s−1. For power reactors during post-refueling cycle startup (operation at small P/S due to low nominal power in the presence of assemblies with high burnup), one has therefore to be careful to adequately dimension the time gate over which the signal is integrated, so as to ensure that the numerical protection system—which computes the neutron flux time-derivative—will not trigger unwanted scramming. Strikingly, both these formal and numerical results directly confirm that fluctuations in a reactor might grow as \(\sqrt{P}\), as long as the time-gate width is larger than the inverse of the delayed neutron time constant. Since this curve allows extracting numerical values such that \({\sigma }_{z}({{\Delta }}t)/\langle {z}_{{{\Delta }}t}\rangle \approx \sqrt{P}\) (with P in MW), at P = 1 MW fluctuations could be of the same order of magnitude as the power itself (depending mainly on the time-gate width).

Spatial correlations and neutron clustering

For spatially resolved characterization of spatial correlations, we have used an ad hoc experimental setup (described above and in the “Methods” section), allowing for simultaneous spatial measurements. The two ex-core NoMAD detectors performed synchronized acquisition of neutron capture events in their 3He tubes over a wide range of reactor core powers, as their distance to the core was sufficiently large to prevent any saturation effect up to 100 mW. The experimental two-point spatial correlation function was defined as

where N1 and N2 are respectively the total number of neutrons detected in a given time bin Δt by all 3He tubes of the bottom NoMAD detector (denoted N1) and of the top NoMAD detector (denoted N2)7,8,24. The first experimental results related to such spatial correlations are presented in Fig. 5a, where the spatial correlation function g defined in Eq. (6) is analyzed at different reactor powers. The long simulation time required to numerically reproduce the different experimental runs (ranging from 0.6 up to 5.5 mW) authorized only to have a partial recovering of the data between 0.6 and 1.5 mW. Both experimental RCF and numerical MORET6 spatial correlation function are in excellent relative agreement. A 1/Pα fit of both curves yields the scaling g ∝ 1/P (simulated data: α = 0.96 ± 0.046, experimental data: α = 1.11 ± 0.044). The correlation function g can be generalized to a “continuous detector” model g(x, y) where x and y are the coordinates of the “detector” points in space. The presence of a peak for small r = ∣x − y∣ would be the signature of neutron clustering. Concerning the experimental behavior of spatial correlations as a function of the distance r between detectors, the positioning of the NoMAD detectors did not allow accurate measurements at very low powers due to the strong attenuation of the neutron signal associated to their positioning; therefore, an empty pincell equipped with four 3He tubes was placed directly at the center of the reactor. The bottom 3He detector taken as a reference, we have performed three measurements of g at increasing distances (between 20 and 70 cm far from this reference detector) and allowed accurate measurements of g(z) at very low power, below the tube saturation threshold (estimated at 5 mW). Here, z refers to the projection of r upon the axis of revolution of the reactor, since the 3He tubes detection device only allowed the detection of correlations integrated over xy-slices of the core. Figure 5b presents two experimental runs (bottom curve: P = 0.63 mW, top curve: P = 0.99 mW) and one simulation result at P = 0.79 mW. The three correlation functions are ordered from lower to higher powers and put into evidence the neutron clustering phenomenon while suggesting a linear decrease of g as a function of z. These findings can be again understood in the light of the branching random walk model: considering an infinite homogeneous medium, and exploiting the presence of a translation symmetry allows assuming that the spatial correlation function depends only on the distance r between detectors, namely, g(x, y) = g(r = ∣x − y∣). In view of the fact that the central pincell is equipped with 3He detectors to measure correlations, since this pincell is placed along the z-axis, the g(r) function must be projected on this axis and, following the derivation presented in the Supplementary Note 3, leads to

where D is the neutron diffusion coefficient (in cm2 s−1), c∞ is the neutron concentration (cm−3), and LT is the typical effective transverse dimension of the reactor. The diffusion approximation (as opposed to the full transport theory treatment, possibly including a continuous-energy description of nuclear data) was used here mainly in order to have a toy-model amenable to exact and easily readable results, to be contrasted to experimental results. For this purpose, we have introduced a series of approximations, including the use of a homogeneous infinite medium, whose validity must be judged based on the predictive power of this model with respect to the experimental findings. It is remarkable that the slope of the correlation function along the z-axis depends on the power of the reactor via c∞

which implies that this slope, normalized by the correlation function at z = 0, only depends on the typical transverse size of the system through

Both the predictions that the slope decays as the inverse of P and that it is linear are confirmed in Fig. 5b and c, respectively. The agreement between experimental correlations and numerical correlations lies within 2-σ and a linear fit of g(z) for numerical results is presented to also reveal the excellent agreement with the prediction of the model of neutron clustering with intrinsic sources given by Eq. (7). Assuming that the typical size of neutron clusters is given by the inverse of the slope \(\left(\right.\partial g/\partial z{\left)\right.}^{-1}\), Eq. (7) also states that this size should increase with P up to reaching the size of the core, which is verified by numerical and experimental results in Fig. 5c. In particular, a strong prediction of the model is that, whenever the core is more decoupled along its transverse dimension (and hence LT ≫ L), the size of the clusters along the axial dimension normalized by the correlations themselves should be of the order of LT. Due to the heterogeneous radial structure of the reactor, this hypothesis is hard to verify and set limits to the predictive capabilities of a diffusion model based on the assumption of a homogeneous infinite medium. However, the numerical results for P = 0.79 mW confirm the hypothesis that LT are one order of magnitude larger than L. Pursuing the approach followed to describe fluctuations, this characterization of spatial correlations suggests that a snapshot of the reactor core during operation should exhibit a non-Poissonian behavior with clustered distributions of neutrons that can be spotted with naked eye (g ≈ 5% on average). Accessing such a snapshot can be performed numerically since the excellent agreement between real and simulated data for macroscopic quantities authorizes to use simulations as a microscopic probe of the nuclear chain reaction. Thus, using the 1.2 mW run, Fig. 6 reports one of these strongly correlated distributions of neutrons through a 2D cut view of the neutron flux (right plot) that can be compared to its time average equivalent (left plot). The center plot shows the projection of both 3D neutron flux maps on the z-axis. This “instantaneous” (i.e. snapshot) view is presented together with its computed (non normalized) spatial correlation function g (central top plot).

a Spatial correlation function g versus reactor power P on a log–log scale using the two NoMAD detectors (simulations: red circles; RCF experiments: blue squares; theory: 1/P fit). The spatial correlations vanishes as 1/P, coherently with the predictions of spatial clustering models. b Spatial correlation function g versus distance z on a lin–lin scale using the inner 3He tubes, for various reactor power levels. Simulated (red circles, for P = 0.79 mW) and experimental (blue squares, bottom curve P = 0.63 mW, top curve: P = 0.99 mW) data are fitted using a linear function predicted by the theory. The typical spatial linear decay of the correlation function signs a clustering effect of the neutron population in the presence of intrinsic sources. c Axial gradient of the spatial correlation function ∂zg versus distance z on a lin–lin scale using the inner 3He tubes (simulations: red circles; RCF experiments: blue squares; theory: −1/P fit). The neutron clusters sizes are inversely proportional to the reactor power. Statistical error bars on the g and its slope ∂zg are estimated using the bootstrapping method, both for simulated and experimental data. Relative errors on the power estimation of experimental data were overestimated at 10%, using the detectors calibration, and error bars on the positioning in z of 3He detectors have been evaluated to be approximately of 1 cm.

The 2D simulated power map is projected onto a 3D cut of the 1.2 mW RCF experiment. a The power map is averaged over 100 s of acquisition time (referred to as the “averaged” power map). b The power map corresponds to an acquisition time of 1 ms (hence it will be referred to as the “snapshot” power map). The corresponding axial power profiles are superimposed in c. In this last figure the noisy profile associated to the “snapshot” view exhibits a non-Poissonian behavior typical of a clustered neutron population, which can be characterized by a peaked spatial correlation function g (d). The statistical error bars appearing in panel c are given by the MORET6 Monte Carlo neutron transport code.

Conclusions

Understanding fluctuations and spatial correlations is essential for the safe operation of nuclear reactors, especially during startup, when stochastic effects are predominant. This is particularly true whenever the core startup relies on weak neutron sources or even on no external neutron source at all31,32, which can be tempting for nuclear operators. A dedicated program led by LANL, the French Institute for Radiological Protection and Nuclear Safety and the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission has been developed, encompassing theoretical and numerical investigations to support experimental observations made in 2017 at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Reactor Critical Facility. These observations reveal a neutron clustering phenomenon characterized by a linear decay of the spatial correlation function, and show that the neutron population occurs through “bursts” giving rise to a blinking behavior of the nuclear core. High-fidelity simulations of the stochastic neutron transport in the reactor (taking into account the sampling of neutron fission events over realistic multiplicity and energy distributions) agree very well with observations, and allow unravelling these clustering and blinking behavior of the core from the time-averages of the neutron population. A simplified stochastic model has been derived in order to interpret these phenomena, relying on the description of spontaneous fissions in addition to neutron-induced fissions. These spontaneous fissions smooth, without completely suppressing, the tendency of neutrons to cluster, and prevent the neutron population from undergoing too large fluctuations, which would cause involuntary reactor shutdown (the “critical catastrophe”). However, it was shown that the stochastic noise of the reactor might be strongly affected by the delayed neutron fraction (and hence by burnup effects, which concomitantly increase intrinsic sources) and might also persist in the deterministic regime, if the time-gate widths used to detect the neutrons are too large: while the critical catastrophe is prevented by intrinsic sources and associated negative reactivity, it can be restored at higher power where the reactivity goes to zero. This recovery of the “critical catastrophe” regime, whenever observed with large time gates, can lead to persisting fluctuations (stochastic noise) which can cause reactor safety issues, since protection systems of power reactors require stable signals to detect and implement proper counter-reactions. Our results therefore expand and complement the investigations of sudden low-frequency variations of the neutron noise threshold in power reactors previously reported in refs. 33,34,35. Concerning spatial correlations, the clustering effect has been shown to be enhanced by the decoupling of the reactor core. A dedicated experimental program to quantify the scaling of spatial correlations with the reactor power and the reactor dominance ratio could offer perspectives to understand long-standing issues related to reactor power tilts (quadrant asymmetries of the power of unknown origin). For instance, radial power tilts in large reactors seem to closely follow the behavior of spatial correlations as they appear to be positively correlated to the reactor size (or decoupling) and to decrease with the reactor power36: this phenomenology could be compatible with a clustering triggered by local reactivity perturbations and enhanced by neutron population control using control rods9,37. Finally, the fact that both fluctuations and spatial correlations are quenched by the presence of neutron leakages and decrease with the coupling intimates that small/coupled reactors should present tempered neutron noise characteristics.

Methods

Experimental setup

The Walthousen RCF at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute is a zero-power education, research, and training reactor with 4.81% enriched UO2 ceramic fuel clad in stainless steel26. The fuel has an active length of 36 inches and the fuel pins are arranged in a square lattice with a pitch of 0.64 inches. The reactor is licensed to operate up to 100 W. Due to the low burnup, the fuel is essentially fresh. RCF is adapted to the sought measurements, for several reasons. First, low-power levels are required to detect fluctuations and correlations. Also, due to the absence of noticeable burnup, the RCF fuel is typically very well characterized, and allows entering the core for direct manipulation of experimental equipment26. Finally, the RCF core is sufficiently large for spatial effects to be relevant for the purpose of the experimental campaign, as supported by preliminary simulations. The detection system used during the experiments was composed of three kinds of detectors. Multiple uncompensated ion chambers and BF3 detectors were used for measuring reactor power. As shown in Fig. 1, one of the central fuel pins was equipped with four small 3He detectors which allowed monitoring the neutron spatial distribution and spatial correlations at very low power, thanks to their small saturation threshold. To reconstruct these observables at higher power, two LANL Neutron Multiplicity 3He Array Detector (NoMAD) systems were placed on the side of the reactor core. Each NoMAD system contains 15 3He tubes embedded in polyethylene and arranged into three rows. Each tube is 15 inches in length38. Further details about the reactor and the detection setup are given in Supplementary Note 4.

Numerical experiment

To support both the design of this experiment and its analysis, ad hoc capabilities were developed within the MORET6 Monte Carlo code (see Supplementary Note 5) so as to accurately simulate both the reactor, the detection system and the nuclear chain reaction. Indeed, estimating fluctuations as well as spatial and temporal correlations can be performed using the so-called “analog” neutron transport39: the objective was to lean on massively parallel computing capabilities to explicitly simulate every single neutron of this sub-Watt nuclear device. The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Fission Library40 has been used to model the emission of correlated fission secondaries from individual realizations of fission processes on an event-by-event basis, up to 20 MeV, for 235U and 238U in the case of neutron-induced fissions, relying on measurements of neutron multiplicity distributions made by Zucker and Holden41. In the case of spontaneous fissions, the multiplicity distribution data of 238U (the main contributor for spontaneous fissions in the RCF reactor) are also provided by Holden and Zucker42. The Terrell’s approximation has been used for the distributions of fission neutrons for 235U (the second contributor for spontaneous fissions in the RCF reactor). The average multiplicity \(\bar{\nu }\) are set to match the values provided by the ENDF/B-VII.1 nuclear data library43. All other nuclear data used in this work also come from ENDF/B-VII.1. While cross-sections and energy-angle distributions contained in evaluated nuclear data libraries play a central role in reactor physics calculations, since they are typically responsible for measurable differences in computed average quantities as reactivity and possibly other tallies, it is worth noting that correlations and fluctuations tallies are however mostly depending on the choice of the fission library, which provides data related to the fluctuation of the fission process. Hence, the data analysis of these quantities does rely only loosely on the choice of the evaluated nuclear data library. The massively parallel simulation campaigns were conducted at the Computing Center for Research and Technology (http://www-hpc.cea.fr/en/complexe/ccrt.htm), using Intel® Xeon® E5-2680 cores. A typical Monte Carlo run required 105 processor.days to simulate the startup of the reactor until convergence of the neutron population. Statistical error bars were calculated using the “boot” library within the R package44, as discussed in ref. 45 in a context of zero power reactor noise study. Systematic errors estimation is discussed in Supplementary Note 5.

Adjustment of simulation parameters

During the experiments, the power calibration of the reactor during operation required special attention. All of the detection systems were used, namely the uncompensated ion chambers and the dedicated ex-core and in-core detection systems (using respectively the two NoMAD detectors and the four 3He tubes, all positioned along the axial dimension of the reactor core). During the analysis, all comparisons between experimental and simulated data were obtained through a “fine tuning” of two simulation parameters (adjustment of the control rod position or of the 235U enrichment). Since the simulation time required to reach the asymptotic time behavior of the power can be extremely long, particularly when the core is close to critical, this procedure is extremely cumbersome: among a set of performed simulations, only the one with the asymptotic power value closest to experimental data is selected.

Data availability

The experimental data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author E.D. The data are not publicly available due to them being generated using export-controlled codes.

Code availability

MCNP6 code was used to calibrate detectors and during the design phase of the experiment. MORET5 and MORET6 codes were used to design the experiment and to analyze the data. All codes are under export control regulations but are available upon request from https://rsicc.ornl.gov and from the OECD Data Bank service https://www.oecd-nea.org/databank/. MORET6 is the next major release of MORET codes series and is available upon request at IRSN.

References

Williams, M. M. R. Random Processes in Nuclear Reactors (Elsevier, 1974).

Pazsit, I. & Pal, L. Neutron Fluctuations (Elsevier, 2008).

Ueki, T. Robust statistical error estimation of local power tallies in Monte Carlo calculation of light water reactor. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 180, 58–68 (2015).

Ueki, T. Universal methodology for statistical error and convergence of correlated Monte Carlo tallies. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 193, 776–789 (2019).

Miao, J. Predicting correlation coefficients for Monte Carlo eigenvalue simulations with multitype branching process. Ann. Nucl. Energy 112, 307–321 (2018).

Verbeke, J. & Petit, O. Universal methodology for statistical error and convergence of correlated Monte Carlo tallies. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 183, 214–228 (2016).

Dumonteil, E. Particle clustering in Monte Carlo criticality simulations. Ann. Nucl. Energy 63, 612–618 (2014).

Zoia, A. Clustering of branching Brownian motions in confined geometries. Phys. Rev. E 90, 042118 (2014).

De Mulatier, C. The critical catastrophe revisited. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2015, p08021 (2015).

Sutton, T. & Mittal, A. Neutron clustering in Monte Carlo iterated-source calculations. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 49, 1211–1218 (2017).

Brown, F. et al. Statistical Tests for Diagnosing Fission Source Convergence and Undersampling in Monte Carlo Criticality Calculations. OECD/NEA report WPNCS SG6 (2021).

Nowak, M. Monte Carlo power iteration: entropy and spatial correlations. Ann. Nucl. Energy 94, 856–868 (2016).

Miao, J. Improving variance convergence rate in Monte Carlo eigenvalue simulations via delayed neutrons. Ann. Nucl. Energy 142, 107376 (2020).

Sun, G. Q. Pattern transitions in spatial epidemics: mechanisms and emergent properties. Phys. Life Rev. 19, 43–73 (2016).

Li, L. Patch invasion in a spatial epidemic model. Appl. Math. Comput. 258, 342–349 (2015).

Dumonteil, E. Spatial extent of an outbreak in animal epidemics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 4239–4244 (2013).

Houchmandzadeh, B. Neutral clustering in a simple experimental ecological community. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 078103 (2008).

Houchmandzadeh, B. Clustering of diffusing organisms. Phys. Rev. E 66, 052902 (2002).

Bailey, N. T. J. The Mathematical Theory of Infectious Diseases and its Applications (Griffin, 1968).

Young, W. R. Reproductive pair correlations and the clustering of organisms. Nature 412, 328–31 (2001).

Dawson, D. The critical measure diffusion process. Z. Wahrscheinlichkeitstheor. Verwandte Gebiete 40, 125–145 (1977).

Cox, J. T. & Griffeath, D. Occupation times for critical branching Brownian motions. Ann. Probabil. 13, 1108–1132 (1985).

Zhang, Y. C. Diffusion reproduction processes. J. Stat. Phys. 58, 849–861 (1990).

Houchmandzadeh, B. Theory of neutral clustering for growing populations. Phys. Rev. E 80, 051920 (2009).

Houchmandzadeh, B. Neutron fluctuations: the importance of being delayed. Phys. Rev. E 92, 052114 (2015).

Arthur, J. Development of a research reactor protocol for neutron multiplication measurements. Prog. Nucl. Energy 106, 120–139 (2018).

Jacquet, O. Capabilities overview of the MORET 5 Monte Carlo code. Ann. Nucl. Energy 82, 74–84 (2015).

Stein, G. & Dubi, C. Stabilization of the stochastic point reactor kinetic equation through power feedback. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 135, 208 (2020).

Pazsit, I. & Yamane, Y. The backward theory of Feynman and Rossi-Alpha methods with multiple emission sources. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 133, 269–281 (1999).

Yamane, Y. & Pazsit, I. Heuristic derivation of rossi-alpha formula with delayed neutrons and correlated source. Ann. Nucl. Energy 25, 1373–1382 (1998).

Williams, M. M. R. & Eaton, M. D. Spatial effects in low neutron source start-up and associated stochastic phenomena. Ann. Nucl. Energy 111, 616–634 (2018).

Ding, Q. et al. Analysis of ex-core source range detector count rate in PWR nuclear power plant. At. Energy Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2019.youxian.0264 (2019).

Seidl, M. Review and historic neutron noise behavior in German KWU built PWRs. Prog. Nucl. Energy 85, 668e675 (2015).

Torres, L. A. Neutron noise analysis of simulated mechanical and thermal-hydraulic perturbations in a PWR core. Ann. Nucl. Energy 126, 242–252 (2019).

Signal Noise Analysis in Nuclear Reactors: when the disturbing role of noise becomes valuable. https://www.psi.ch/en/lrt/scientific-highlights/signal-noise-analysis-in-nuclear-reactors (2017).

Sargeni, A. et al. The impact of heavy reflectors on power distribution perturbations in large PWR reactor cores. Ann. Nucl. Energy 94, 566–575 (2016).

Dumonteil, E. Clustering and traveling waves in the Monte Carlo criticality simulation of decoupled and confined media. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 49, 1157–1164 (2017).

Cutler, T. et al. Copper and polyethylene-reflected plutonium-metal-sphere subcritical measurements. In International Handbook of Evaluated Criticality Safety Benchmark Experiments (OECD Nuclear Energy Agency, 2019).

Petit, O. Analog neutron transport for nuclear instrumentation applications with the Monte Carlo Code TRIPOLI-4. J. Nucl. Technol. 192, 259–263 (2015).

Verbeke, J., Randrup, J. & Vogt, R. Fission reaction yield algorithm FREYA for event-by-event simulation of fission. Comp. Phys. Commun. 191, 178–202 (2015).

Zucker, M. S. & Holden, N. E. Energy Dependence of the Neutron Multiplicity Pν in Fast Neutron Induced Fission of 235,238U and 239Pu. BNL Internal Report 38491 (Brookhaven National Laboratory, 1986).

Holden, N. E. & Zucker, M. S. A Reevaluation of the Average Prompt Neutron Emission Multiplicity Values from Fission of Uranium and Transuranium Nuclides. BNL Internal Report 35513 (Brookhaven National Laboratory, 1984).

Chadwick, M. B. Special issue on ENDF/B-VII.1 library. Nucl. Data Sheets 112, 2887–2996 (2011).

Davison, A. C. & Hinkley, D. V. Bootstrap Methods and their Application. Vol. 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Endo, T. & Yamamoto, A. Comparison of theoretical formulae and bootstrap method for statistical error estimation of Feynman-α method. Ann. Nucl. Energy 124, 606–615 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the DOE Nuclear Criticality Safety Program, funded and managed by the National Nuclear Security Administration for the Department of Energy, as well as by IRSN. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Peter Caracappa for his help with the experiment, Dr. Yaron Danon for his support, and the Senior Reactor Operators who operated the reactor during the experiments: Glenn Winters, Dr. Jason Thompson, Emily Frantz, and Alexander Roaldsand.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.D., J.H., W.M., and N.T. designed the experiments. R.B., T.C., E.D., T.G., J.H., G.M.K., A.M.S., W.M., M.N., and N.T. performed the experiments. B.D., E.D., and A.Z. did the stochastic modeling. All author contributed to the data analysis. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dumonteil, E., Bahran, R., Cutler, T. et al. Patchy nuclear chain reactions. Commun Phys 4, 151 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-021-00654-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-021-00654-9

This article is cited by

-

Asymptotic moments of spatial branching processes

Probability Theory and Related Fields (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.