Abstract

Although the dielectric constant of plasma depends on electron collision time as well as wavelength and plasma density, experimental studies on the electron collision time and its effects on laser-matter interactions are lacking. Here, we report an anomalous regime of laser-matter interactions generated by wavelength dependence (1.2–2.3 µm) of the electron collision time in plasma for laser filamentation in solids. Our experiments using time-resolved interferometry reveal that electron collision times are small (<1 femtosecond) and decrease as the driver wavelength increases, which creates a previously-unobserved regime of light defocusing in plasma: longer wavelengths have less plasma defocusing. This anomalous plasma defocusing is counterbalanced by light diffraction which is greater at longer wavelengths, resulting in almost constant plasma densities with wavelength. Our wavelength-scaled study suggests that both the plasma density and electron collision time should be systematically investigated for a better understanding of strong field laser-matter interactions in solids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is well known that the optical properties of materials, such as light reflection, refraction, and absorption are described by dielectric constants. When a high-intensity laser interacts with a material, bound electrons are ionized, creating plasma. The complex dielectric constant for plasma1 is given by \(\epsilon\left( \omega \right) = 1 - \omega _{\mathrm{p}}^2/\omega \left( {\omega + i/\tau _{\mathrm{c}}} \right)\), where \(\omega\) is the optical angular frequency, \(\omega _{\mathrm{p}}\) is the plasma frequency which is proportional to the square root of the plasma density, and τc represents the electron collision time. Therefore, to fully determine the optical properties of plasma, it is critical to have the information on the plasma density, as well as the electron collision time. In particular, the electron collision time plays an important role in high-density plasma, where free electrons frequently collide with other electrons, ions, and atoms. Although there exist a lot of reports on plasma density measurements, there are only a handful of experiments that measured electron collision times2,3 and thus τc is still a debatable parameter. For instance, the electron collision times used in previous work for the laser–matter interaction in fused silica2,3,4 vary significantly, ranging from 0.2 to 23 fs.

One of the key light–matter interaction phenomena involving light refraction and absorption in plasma is laser filamentation, which is high-intensity laser self-guidance due to the dynamic balance between optical Kerr effect (self-focusing) and plasma defocusing/diffraction5,6,7,8. Laser filamentation has been an active topic of research because of its fundamental novelty6,7,8, as well as various important applications, such as few-cycle pulse generation9,10, terahertz generation11,12, remote sensing13, long-lived waveguides14, rain-making15, and lightning control16. Modern laser technology enables researchers to study laser filamentation in gases17,18 and solids19,20,21,22,23 and other strong field laser–matter interactions, such as high-order harmonic generation (HHG)24 in the mid-infrared (IR) and long-wavelength IR. Since plasma defocusing and diffraction generally increase as the driver wavelength increases, the peak intensity and plasma density in a laser filament are expected to become smaller at longer wavelengths25,26. Several theoretical studies in gases/air have shown similar trends27,28 and moreover, recent experimental work in air29 using a 10-µm CO2 laser has reported a long megafilament with low-plasma densities (<1016 cm−3). As a comparison, a theoretical study on wavelength-scaled filamentation in a solid has predicted a similar monotonic decrease in the plasma density, with increasing wavelength for the driver wavelengths in the anomalous group-velocity dispersion (GVD) regime30. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no systematic experimental investigation on wavelength dependence of the plasma dynamics in laser filamentation.

Here, we report on experimental and theoretical wavelength scaling of the plasma dynamics in femtosecond laser filamentation in solids. Time-resolved interferometry is performed to simultaneously measure plasma densities and electron collision times in filaments by varying the pump wavelength from λ = 1.2–2.3 μm. The plasma densities show little change for different wavelengths, which is in contrast to the expected trend of monotonic decrease with increasing wavelength. Furthermore, the measured electron collision times are smaller than 1 femtosecond (fs) and decrease as the driver wavelength increases, which is due to hotter electron generation and increased electron excursion length in filaments at longer wavelengths. Our analysis shows that the observed wavelength dependence of the electron collision time creates an anomalous regime of light defocusing under plasma: longer wavelengths have less plasma defocusing. Simulations using the measured electron collision times successfully reproduce the measured wavelength dependence of the plasma density. Our work suggests that the electron collision time in plasma should be systematically studied for a precise understanding of strong field laser–matter interactions in solids.

Results

Plasma density measurement

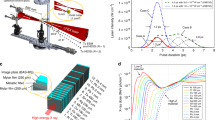

Time-resolved experiments are performed using variable-wavelength driver (pump) pulses from an optical parametric amplifier (OPA) that is pumped by a linearly polarized Ti:sapphire laser system [1−kHz repletion rate, 800-nm central wavelength, 45-fs full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) pulse duration]. The pump wavelength (λ) is changed between 1.2 and 2.3 μm with a 0.1-µm interval. However, we do not use 1.6-μm wavelength in our experiments because of its instability. Filaments are generated in a 2.5-cm long fused silica sample. Since zero GVD occurs near 1.27 μm for fused silica, wavelengths longer than 1.3 μm belong to the anomalous-GVD regime. The input peak powers are smaller than six times the critical power for self-focusing Pcr to avoid multifilaments and generate stable single filaments. We focus the pump beams using a 15-cm focal length CaF2 lens and the geometrical foci are located 2-mm before the input face of the sample to ensure that plasma is generated through self-focusing with minimal help from CaF2 lens. First, we characterize the input beams at all the wavelengths by measuring the focused mode sizes, pulse durations (60–130 fs), spectra, and chirp. For measurements of plasma densities in filamentation, we use femtosecond time-resolved single-shot interferometry, in which a weak collimated 800-nm beam acts as a probe and orthogonally traverses the pump-generated filamentation region. Single-shot measurements of maximum plasma densities near the onset of stable filaments are performed by decreasing the pulse repetition rate from 1 kHz to 50 Hz using optical choppers (see the “Methods” and Supplementary Note 1). We use the standard Fourier transformation technique31 for phase extraction and Abel inversion, assuming cylindrical symmetry for retrieving the refractive index change (Δn) via plasma from the measured phase. First, based on the assumption \(\omega _{{\mathrm{pr}}}\tau _{\mathrm{c}} \gg 1\), where ωpr is the 800-nm probe angular frequency, which is the standard assumption for most cases (e.g., gases), we retrieve the plasma density using \({\Delta}n = - \rho /2\rho _{\mathrm{c}}\), where ρ is the plasma density, \(\rho _{\mathrm{c}} = \varepsilon _0m_{\mathrm{e}}^ \ast \omega _{{\mathrm{pr}}}^2/e^2\) is the critical plasma density for the probe, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity, e is the electron charge, and \(m_{\mathrm{e}}^ \ast\) is the reduced electron mass. We will discuss the validity of the assumption of \(\omega _{{\mathrm{pr}}}\tau _{\mathrm{c}} \gg 1\) and its effect on the measured plasma densities later. According to Fig. 1a, the measured plasma densities show little change for different wavelengths32. Details on data averaging and comparison of two different averaging methods are provided in Supplementary Note 2. This result is in contrast to the expected trend based on filaments in air/gases: monotonic decrease in the plasma density because of greater diffraction and plasma defocusing at longer wavelengths.

a Measured plasma density scaling with wavelength. Simulated plasma density scaling using b multiphoton ionization (MPI) and collisional ionization, and c full Keldysh ionization (FKI) and collisional ionization. Simulations are performed with the measured parameters (measured para.,) [red diamond and black square] and also with the same (input beam) parameters (same para.) (P = 5Pcr, τp = 70 fs, w0 = 60 μm and no chirp) [blue triangle and magenta downward triangle]. The full list of measured parameters is in the table displayed in d. In the simulations, constant electron collision times τc = 1.7 and 3 fs are used for all the wavelengths. d Table of experimental parameters; λ: wavelength, τp: FWHM pulse duration, w0: 1/e2 beam radius, and P/Pcr: normalized input peak power with respect to critical power. The error bars in a correspond to the standard deviation of 35 laser shots.

Numerical simulations

To compare with experiments and understand the underlying dynamics, we perform numerical simulations by solving the nonlinear envelope equation33,34 in fused silica, using the experimental parameters. The electric field propagation equation is coupled with the plasma generation equation considering optical field ionization (OFI), collisional ionization35, and plasma recombination, which is given by

Here, \(\rho\) is the plasma density, \(\rho _0\)is the neutral atomic density, and \(W(I)\) is the OFI rate. For OFI, we use either multiphoton ionization (MPI) or full Keldysh ionization (FKI)36, which describes both MPI and tunneling ionization depending on driver wavelength and intensity. The second term in Eq. (1) represents collisional ionization. Here, \(\sigma _{{\mathrm{IB}}}\) is the inverse Bremsstrahlung coefficient, which is given by the real part of \(\sigma _{\mathrm{c}}\left( \omega \right) = \omega _0^2\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\left( {1 + i\omega \tau _{\mathrm{c}}} \right)/\left[ {n\left( \omega \right)c\rho _{\mathrm{c}}\left( {1 + \omega ^2\tau _{\mathrm{c}}^2} \right)} \right]\), where \(\omega _0\) is the driver laser angular frequency, \(n\left( \omega \right)\) is the refractive index, and \(\rho _c\) is the critical plasma density for the driver laser. \(U_{\mathrm{i}}\) is the fused silica bandgap energy (9 eV) and \(I\) is the laser intensity. The plasma recombination time \(\tau _{\mathrm{r}}\) in fused silica is 150 fs (ref. 37). More details about the nonlinear index measurement via z-scan38 and the simulation are provided in Supplementary Notes 3 and 4, respectively.

We first use the MPI rate for OFI and constant τc’s for all the wavelengths in the simulation. In detail, we perform two sets of simulations with two constant τc’s: τc \(=\) 1.7 fs (ref. 2) and 3 fs (ref. 33). The calculated plasma density with MPI (Fig. 1b) shows a monotonic decrease with increasing wavelength for both τc’s, which thus cannot reproduce the experiment. Next, we use the FKI rate for OFI, which is known to be more accurate than the MPI rate. However, even with FKI, the calculated plasma density still monotonically decreases with increasing wavelength (Fig. 1c). As shown in Fig. 1d, our experimental parameters such as pulse durations and beam sizes are different at different wavelengths. Thus, we also perform simulations using the same parameters for all the wavelengths (input power of 5Pcr, pulse duration of 70 fs, beam radius of 60 μm and no chirp) to investigate the effect. However, the simulations with the same parameters also show a similar monotonic decrease (dashed lines in Fig. 1b, c). We hypothesize that the discrepancy between the experiment and the simulation comes from uncertainties in the electron collision time because \(\sigma _{\mathrm{c}}\left( \omega \right)\), which critically affects both collisional ionization and light defocusing/absorption, is a function of τc. As mentioned, the electron collision times used in previous work using fused silica vary significantly4, ranging between 0.2 and 23 fs for 800-nm lasers.

Electron collision time measurement

To confirm our hypothesis, we directly measure electron collision times in laser filaments as a function of driver wavelength. Our analysis shows that time-resolved interferometry enables simultaneous measurements of the plasma density and electron collision time in a single shot via phase shift and probe absorption, for which the expression is given by (see Supplementary Note 5 for further details)

Here, \({\mathrm{{\Delta}}}\phi\) is the measured phase change and ln(E0/Ep) represents the probe absorption due to plasma, where Ep and E0 are the probe electric fields with and without plasma, respectively. Examples of single-shot two-dimensional phase and amplitude are shown in Fig. 2a, b and Fig. 2c, d for λ = 1.2 and 2.3 μm, respectively. The positive phases in Fig. 2a and Fig. 2c are due to cross-phase modulation generated by pump pulses. The measured electron collision time versus wavelength is shown in Fig. 2e. The measured electron collision times are very small (<1 fs) and not constant, showing a decrease from τc ~ 0.7 to τc ~ 0.4 fs with increasing wavelength. Examples of extracted two-dimensional electron collision times are provided in Supplementary Note 6. Our observation is reproducible and one more data set, which shows similar wavelength scaling, is provided in Supplementary Note 7.

Examples of two-dimensional profiles of phase and electric field absorption (normalized probe electric field amplitude) during filamentation for a, b 1.2 μm and for c, d 2.3 μm measured by single-shot femtosecond time-resolved interferometry. e Measured electron collision time versus wavelength. The error bars in e correspond to the standard deviation of 35 laser shots.

Discussion

Since the measured electron collision times are small, the assumption of \(\omega _{{\mathrm{pr}}}\tau _{\mathrm{c}} \gg 1\) is not quite valid, and thus the plasma density measurement via interferometry should be reexamined. We reextract the plasma densities using the index change \({\Delta}n = - \rho /2\rho _{\mathrm{c}}\!\! \ast\), where \(\rho _{\mathrm{c}} \!\!\ast = \varepsilon _0m_{\mathrm{e}}\!\! \ast \omega _{{\mathrm{pr}}}^2\left( {1 + \left( {\omega _{{\mathrm{pr}}}\tau _{\mathrm{c}}} \right)^{ - 2}} \right)/e^2\) is the modified critical plasma density considering the electron collision time. As shown in Fig. 3a (black solid line), although consideration of \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\) increases the extracted plasma densities, the trend remains almost the same (almost constant plasma densities for different driver wavelengths). Next, we perform numerical simulations using the measured collision times with the FKI and collisional ionization models (Eq. 1). As shown in Fig. 3b (black solid line), the simulations are in very good agreement with the experiments. In contrast, the simulations using a couple of measured electron collision times (\(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\) = 0.7 and 0.4 fs), but assuming constant \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\) for all \(\lambda\)’s still show a decrease with increasing wavelength [\(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\) = 0.4 (red dashed line) and 0.7 fs (blue dotted line) in Fig. 3b].

a Measured plasma density analysis with (black circle) and without (red square) the assumption of \(\omega _{{\mathrm{pr}}}\tau _{\mathrm{c}} \gg 1\), where \(\omega _{{\mathrm{pr}}}\) is the probe angular frequency and \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\) is the electron collision time. b Simulated plasma densities versus wavelength with constant \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\) = 0.4 fs (red dashed line), 0.7 fs (blue dotted line), and with measured collision times (black solid line). Simulation results using the measured collision times agree well with the observed wavelength scaling of plasma density. The error bars correspond in a to the standard deviation of 35 laser shots.

We carry out further analysis on the effect of the measured electron collision times on collisional ionization and plasma defocusing. Figure 4a shows calculations of the inverse Bremsstrahlung coefficient σIB versus τc for a few wavelengths, which shows a decrease in \(\sigma _{{\mathrm{IB}}}\) as τc decreases for τc < 1 fs. Since collisional ionization is proportional to σIB (Eq. 1), this indicates that collisional ionization should be greater at larger electron collision times for τc < 1 fs. However, as shown in Fig. 3b, the simulation with τc = 0.4 fs shows higher plasma densities than that with \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}} =\) 0.7 fs. This suggests that plasma defocusing should be more important than collisional ionization. According to the calculated imaginary part of \(\sigma _{\mathrm{c}}\left( \omega \right)\) related to plasma defocusing (Fig. 4b, c), an anomalous regime of light defocusing under plasma is created for τc \(< 1\) fs: longer wavelengths have less plasma defocusing. This is in contrast to the well-known normal regime, where plasma defocusing becomes greater with increasing wavelength, which is the case for gases/air (trend in Fig. 4b for \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\, > \, 1\) fs). In this, observed anomalous regime, plasma densities and thus filament intensities should be large even at long wavelengths. Our calculations confirm that the clamping intensities in filaments at long wavelengths with the measured \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\)’s are larger than those with a constant \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\) = 1.7 fs (see Fig. 5a and additional simulation data in Supplementary Note 8). These relatively high-intensity filaments at long wavelengths should enhance HHG and may facilitate attosecond pulse generation in solids39,40,41 due to enhanced ponderomotive energy (cycle-averaged kinetic energy of a free electron). However, an important question arises here: why do the plasma density and filament intensity not increase with increasing wavelength in the anomalous plasma defocusing regime? We think it is because the anomalous plasma defocusing is counterbalanced by light diffraction, which is greater at longer wavelengths.

a The inverse Bremsstrahlung coefficient \(\sigma _{{\mathrm{IB}}}\) = Real [\(\sigma _c\left( \omega \right)\)]), which is related to collisional ionization, versus electron collision time for a few wavelengths. b, c Dependence of plasma defocusing (Imag [\(\sigma _{\mathrm{c}}\left( \omega \right)\)]) on electron collision time (\(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\)) at \(\lambda\,=\,\)1.2 μm (black solid line), \(\lambda\,=\,\) 1.7 μm (red dashed line), \(\lambda\,=\,\)2 μm (blue dotted line), and \(\lambda\,=\,\)2.3 μm (magenta dashed-dotted line). Plasma defocusing increases with increasing wavelength for \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\, > \, 1\) fs, whereas it decreases with increasing wavelength for \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\, <\, 1\) fs as shown in c, which is a zoomed-in figure for the shaded area in b.

Calculated a clamping intensities with measured \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\)’s and constant \(\tau _c =\) 1.7 fs, b pondermotive energies (\(U_{\mathrm{p}}\)), and c excursion lengths (\(x_{\mathrm{c}}\)) are shown for filamentation at different wavelengths. d The calculated electron collision time as a function of electron temperature. Clamping intensities from simulations in a (black solid line) are used to calculate the ponderomotive energies in b and excursion lengths in c.

Finally, we attribute the observed decrease in electron collision time with increasing wavelength to two reasons: first, it is because of larger ponderomotive energy \(U_{\mathrm{p}} \propto \lambda ^2I\) for longer-wavelength filaments (shown in Fig. 5b), which results in more heating of free electrons and frequent electron-neutral collisions. Second, it is because of larger free electron excursion length \(\left( {x_{\mathrm{c}} \propto \lambda ^2I^{0.5}} \right)\) at longer wavelengths (shown in Fig. 5c), which results in higher probabilities of electron collision with neighbor atoms. The simulation with the measured \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\)’s shows that the filament intensity does not decrease much even at long wavelengths (only ~35% decrease as shown in the black solid line of Fig. 5a). Note that both \(U_{\mathrm{p}}\) and \(x_{\mathrm{c}}\) depend on \(\lambda ^2\) and thus, the wavelength is more important than the intensity for their scaling. For further details related to electron heating, the electron-neutral collision frequency (\({\upnu}_{{\mathrm{en}}}\))42,43 is given by \({\upnu}_{\mathrm{en}}[ {\mathrm{s}}^{-1}] = 2 \times 10^{-7}({\rho} _{0} - {\rho} )T_{\mathrm{e}}^{1/2}\), where \(\rho _0\) is the neutral atomic density in cm−3 and \(T_{\mathrm{e}}\) is the free electron temperature in eV. Since the electron temperature should increase at longer wavelengths due to larger ponderomotive energy, the electron collisional frequency (time) should increase (decrease) with increasing wavelength (i.e.,\({\upnu}_{{\mathrm{en}}} = 1/\tau _c \propto T_{\mathrm{e}}^{{\mathrm{1/2}}}\)). Note that \({\upnu}_{{\mathrm{en}}}\) should dominate over electron–electron and electron–ion collisions due to weak ionization (<0.1%) in fused silica under the filamentation regime. We calculate \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\) considering various types of electron collisions as a function of \(T_{\mathrm{e}}\) (Supplementary Fig. S14a). Figure 5d shows that the calculation successfully reproduces the measured decrease of \(\tau _{\mathrm{c}}\) with increasing wavelength based on the simple, but reasonable assumption of \(U_{\mathrm{p}} \propto T_{\mathrm{e}}\) (more precisely \(U_{\mathrm{p}} = 3T_{\mathrm{e}}/2\)). More details on calculations of electron collision time are provided in Supplementary Note 9, wherein we also discuss the effect of pulse durations on electron collision times.

In conclusion, we experimentally and theoretically investigate wavelength scaling of the plasma density and electron collision time in laser filamentation in fused silica with driver wavelengths ranging between 1.2 and 2.3 μm. The measured plasma densities show little change for different wavelengths, which is in contrast to the expected trend of monotonic decrease with increasing wavelength. As a comparison, the measured electron collision times are smaller than 1 fs and decrease with increasing wavelength. This is attributed mainly to hotter electron generation in longer-wavelength filaments via ponderomotive heating. Most importantly, the observed electron collision times create an anomalous regime of light defocusing under plasma: longer wavelengths have less plasma defocusing. Our simulation using the measured electron collision times successfully reproduces the measured wavelength scaling of plasma density. Furthermore, the simulations predict that the filament peak intensities in the mid-IR can be comparable to those in the near-IR, suggesting enhanced HHG and attosecond pulse generation in solids, using mid-IR filaments. Although our wavelength-scaled study is performed in laser filamentation, the analysis presented here suggests that the electron collision time is an important parameter in all fields of laser–plasma interactions, since it can critically affect the dielectric constant of plasma and collisional ionization. Therefore, both plasma density and electron collision time should be systematically investigated to precisely understand strong field laser–matter interactions in solids.

Methods

OPA beam characterization

We measure the focused mode size of each wavelength by imaging it onto a pyroelectric camera, using a 10-cm focal length imaging lens. For pulse duration measurements, a second-harmonic generation autocorrelator is used with a BBO crystal and a Si photodiode for λ = 1.2–1.9 μm, and an AgGaS2 crystal and an InGaAs photodiode for λ = 2–2.3 μm. The magnitude of chirp is estimated by \(C^2 = \left[ {t_{\mathrm{p}}^2\left( C \right)/t_{\mathrm{p}}^2\left( 0 \right) - 1} \right]/t_{\mathrm{p}}^4\left( C \right)\), where \(t_{\mathrm{p}}(C)\) is the measured pulse duration via autocorrelation, and \(t_{\mathrm{p}}(0)\) is the transform limited-pulse duration, which is estimated from the measured spectrum at each wavelength. The sign of the chirp is determined by propagating each pulse through fused silica samples of various thicknesses. The chirp is positive for \(\lambda = \) 1.2–1.7 μm, and negative for \(\lambda =\)1.8–2.3 μm. The experimental parameters for all the wavelengths are provided in Fig. 1d.

Time-resolved single-shot interferometry

The experimental setup (shown in Supplementary Fig. S1a) is composed of a standard pump–probe scheme and spatial interferometry. An OPA pump beam (1.2–2.3 µm) generates a filament in a 2.5-cm long fused silica sample and a low-energy collimated 800-nm probe beam orthogonally traverses the pump-generated filamentation region. Then, the probe is magnified and collimated using a 10× objective lens and a 50-cm focal length lens (4-f scheme) and is sent to an interferometer, in which a charge-coupled device camera records an interferogram. To achieve single-shot interferometry measurements, we decrease the pulse repetition rate from 1 kHz to 50 Hz, using synchronized optical choppers in both pump and probe arms. We control the time delay between pump and probe using a motorized translational stage in the probe arm, but we set at near-zero delay, for which we observe the maximum plasma densities near the onset of stable filaments. In addition, filament formation is monitored by a combination of a 4× objective lens and a digital camera located above the fused silica sample. To check the accuracy of our interferometry analysis for extracting plasma densities and electron collision times, we perform simulations using the conditions similar to those in our experiments (see Supplementary Note 10).

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors upon request.

Code availability

The computer codes used for data analysis and numerical simulations are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Boyd, R. W. Nonlinear Optics, 3rd edn (Academic, 2008).

Sun, Q. et al. Measurement of the collision time of dense electronic plasma induced by a femtosecond laser in fused silica. Opt. Lett. 30, 320 (2005).

Papazoglou, D. G. & Tzortzakis, S. Physical mechanisms of fused silica restructuring and densification after femtosecond laser excitation [Invited]. Opt. Mater. Express 1, 625 (2011).

Gulley, J. R. & Dennis, W. M. Ultrashort-pulse propagation through free-carrier plasmas. Phys. Rev. A 81, 033818 (2010).

Braun, A. et al. Self-channeling of high-peak-power femtosecond laser pulses in air. Opt. Lett. 20, 73 (1995).

Chin, S. L. et al. The propagation of powerful femtosecond laser pulses in opticalmedia: physics, applications, and new challenges. Can. J. Phys. 83, 863–905 (2005).

Couairon, A. & Mysyrowicz, A. Femtosecond filamentation in transparent media. Phys. Rep. 441, 47–189 (2007).

Bergé, L., Skupin, S., Nuter, R., Kasparian, J. & Wolf, J.-P. Ultrashort filaments of light in weakly ionized, optically transparent media. Rep. Prog. Phys. 70, 1633–1713 (2007).

Hauri, C. P. et al. Generation of intense few-cycle laser pulses through filamentation - parameter dependence. Opt. Express 13, 7541 (2005).

Stibenz, G., Zhavoronkov, N. & Steinmeyer, G. Self-compression of millijoule pulses to 7.8 fs duration in a white-light filament. Opt. Lett. 31, 274 (2006).

D’Amico, C. et al. Conical forward THz emission from femtosecond-laser-beam filamentation in air. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 235002 (2007).

Kim, K. Y., Taylor, A. J., Glownia, J. H. & Rodriguez, G. Coherent control of terahertz supercontinuum generation in ultrafast laser–gas interactions. Nat. Photonics 2, 605–609 (2008).

Kasparian, J. et al. White-light filaments for atmospheric analysis. Science 301, 61–64 (2003).

Jhajj, N., Rosenthal, E. W., Birnbaum, R., Wahlstrand, J. K. & Milchberg, H. M. Demonstration of long-lived high-power optical waveguides in air. Phys. Rev. X 4, 011027 (2014).

Rohwetter, P. et al. Laser-induced water condensation in air. Nat. Photonics 4, 451–456 (2010).

Diels, J.-C., Bernstein, R., Stahlkopf, K. E. & Zhao, X. M. Lightning control with lasers. Sci. Am. 277, 50–55 (1997).

Mitrofanov, A. V. et al. Mid-infrared laser filaments in the atmosphere. Sci. Rep. 5, 8368 (2015).

Liang, H. et al. Mid-infrared laser filaments in air at a kilohertz repetition rate. Optica 3, 678 (2016).

Liang, H. et al. Three-octave-spanning supercontinuum generation and sub-two-cycle self-compression of mid-infrared filaments in dielectrics. Opt. Lett. 40, 1069 (2015).

Silva, F. et al. Multi-octave supercontinuum generation from mid-infrared filamentation in a bulk crystal. Nat. Commun. 3, 807 (2012).

Shumakova, V. et al. Multi-millijoule few-cycle mid-infrared pulses through nonlinear self-compression in bulk. Nat. Commun. 7, 12877 (2016).

Marcinkevičiūtė, A. et al. Femtosecond filamentation and supercontinuum generation in bulk silicon. Opt. Lett. 44, 1343 (2019).

Qu, S. et al. Long-wavelength-infrared laser filamentation in solids in the near-single-cycle regime. Opt. Lett. 45, 2175 (2020).

Popmintchev, T. et al. Bright coherent ultrahigh harmonics in the keV X-ray regime from mid-infrared femtosecond lasers. Science 336, 1287–1291 (2012).

Shim, B., Schrauth, S. E. & Gaeta, A. L. Filamentation in air with ultrashort mid-infrared pulses. Opt. Express 19, 9118 (2011).

Panagiotopoulos, P., Whalen, P., Kolesik, M. & Moloney, J. V. Super high power mid-infrared femtosecond light bullet. Nat. Photonics 9, 543–548 (2015).

Bergé, L., Rolle, J. & Köhler, C. Enhanced self-compression of mid-infrared laser filaments in argon. Phys. Rev. A 88, 023816 (2013).

Geints, Y. E. & Zemlyanov, A. A. Near- and mid-IR ultrashort laser pulse filamentation in a molecular atmosphere: a comparative analysis. Appl. Opt. 56, 1397 (2017).

Tochitsky, S. et al. Megafilament in air formed by self-guided terawatt long-wavelength infrared laser. Nat. Photonics 13, 41–46 (2019).

Grynko, R. I., Nagar, G. C. & Shim, B. Wavelength-scaled laser filamentation in solids and plasma-assisted subcycle light-bullet generation in the long-wavelength infrared. Phys. Rev. A 98, 023844 (2018).

Takeda, M., Ina, H. & Kobayashi, S. Fourier-transform method of fringe-pattern analysis for computer-based topography and interferometry. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 72, 156 (1982).

Nagar, G. C., Dempsey, D. & Shim, B. in Frontiers in Optics / Laser Science FM4C.7 (Optical Society of America, 2020).

Durand, M. et al. Self-guided propagation of ultrashort laser pulses in the anomalous dispersion region of transparent solids: a new regime of filamentation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 115003 (2013).

Couairon, A. et al. Practitioner’s guide to laser pulse propagation models and simulation. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 199, 5–76 (2011).

Stuart, B. C., Feit, M. D., Rubenchik, A. M., Shore, B. W. & Perry, M. D. Laser-induced damage in dielectrics with nanosecond to subpicosecond pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 2248–2251 (1995).

Keldysh, L. V. Ionization in the field of a strong electromagnetic wave. Sov. Phys. JETP 47, 1945 (1965).

Audebert, P. et al. Space-time observation of an electron gas in SiO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1990–1993 (1994).

Sheik-Bahae, M., Said, A. A., Wei, T.-H., Hagan, D. J. & Van Stryland, E. W. Sensitive measurement of optical nonlinearities using a single beam. IEEE J. Quantum Electron 26, 760–769 (1990).

Ghimire, S. et al. Observation of high-order harmonic generation in a bulk crystal. Nat. Phys. 7, 138–141 (2011).

Krausz, F. & Ivanov, M. Attosecond physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 163–234 (2009).

Chang, Z., Corkum, P. B. & Leone, S. R. Attosecond optics and technology: progress to date and future prospects [Invited]. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 33, 1081 (2016).

Chimier, B. et al. Damage and ablation thresholds of fused-silica in femtosecond regime. Phys. Rev. B 84, 094104 (2011).

Peñano, J. R., Sprangle, P., Hafizi, B., Manheimer, W. & Zigler, A. Transmission of intense femtosecond laser pulses into dielectrics. Phys. Rev. E 72, 036412 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Olga Kosareva and Vitaly E. Gruzdev for useful discussions. This work is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF; Grant No. PHY-1707237 and Grant No. PHY-2010365), U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR; Grant No. FA9550-18-1-0223).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.C.N. and B.S. conceived and designed the study. G.C.N. and D.D. performed the experiments, and analyzed the data under the supervision of B.S. G.C.N. and B.S. performed the numerical modeling and simulations. All the authors wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagar, G.C., Dempsey, D. & Shim, B. Wavelength scaling of electron collision time in plasma for strong field laser-matter interactions in solids. Commun Phys 4, 96 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-021-00600-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-021-00600-9

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.