Abstract

How a Mott insulator develops into a weakly coupled metal upon doping is a central question to understanding various emergent correlated phenomena. To analyze this evolution and its connection to the high-Tc cuprates, we study the single-particle spectrum for the doped Hubbard model using cluster perturbation theory on superclusters. Starting from extremely low doping, we identify a heavily renormalized quasiparticle dispersion that immediately develops across the Fermi level, and a weakening polaronic side band at higher binding energy. The quasiparticle spectral weight roughly grows at twice the rate of doping in the low doping regime, but this rate is halved at optimal doping. In the heavily doped regime, we find both strong electron-hole asymmetry and a persistent presence of Mott spectral features. Finally, we discuss the applicability of the single-band Hubbard model to describe the evolution of nodal spectra measured by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) on the single-layer cuprate La2−xSrxCuO4 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.15). This work benchmarks the predictive power of the Hubbard model for electronic properties of high-Tc cuprates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the most important questions in the field of quantum materials is the nature of states that emerge from a doped Mott insulator1,2. This is a key prerequisite to understanding the development of high-Tc superconductivity via hole or electron doping from the Mott phase3,4. Furthermore, this helps elucidate why and how the cuprates are different from other doped Mott insulators. With ability to resolve single-particle energy-momentum spectra, angle-resolved photoemission (ARPES) has helped to determine a starting point to modeling cuprates – the doped Hubbard model5. Early on it was shown that strong correlations, in the form of the on-site Hubbard U, lead to an antiferromagnetic (AFM) state from a predominantly Cu 3d9 configuration6. When a single hole is created by photoemission, it disperses from (π/2, π/2) towards the Γ point, which abruptly falls in intensity near the zone center—the so-called "waterfall”7,8,9,10. Rather than dispersing as a free quasiparticle, the low-energy band in a Mott insulator can be well fitted with a velocity on the scale of the spin exchange J ~ 120 meV11,12,13,14. These basic observations of a Mott insulator lie within the framework of the Hubbard model.

In doped Mott insulators, recent experimental and theoretical progress further extends Hubbard model’s descriptiveness. On the experimental side, ARPES and resonant inelastic x-ray scattering (RIXS) have shown evidence of strong correlations15,16,17,18 and collective spin excitations19,20,21,22,23 far beyond the Mott phase, which cannot be addressed using weak-coupling theory. Despite such success, clearly, there are also experimental observations that seem to lie beyond the simple Hubbard and t − J models. An outstanding example is the ~ 200 meV linewidth of the ARPES spectrum even at (π/2, π/2)7,24, where a single hole described by the t − J model has no phase space to decay11,12. The correct linewidth was obtained only by considering the lattice polaronic effect25,26,27,28, which becomes less dressed at higher dopings due to screening29,30,31. Moreover, in many doped Mott insulators, such as the nickelates32, manganites33, and cobaltates34, doped carriers cause insulating charge structures rather than superconductivity35. While stripe order has also been observed in cuprates, the magnitude is not nearly as strong as in other transition metal oxides36. This difference also led to the consideration of many material-specific degrees of freedom beyond the prototypical Mott insulator, including static and dynamic lattice effects37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. Therefore, both for aspects specific to cuprates and those generic to correlated materials, one may wonder, to what extent exactly can the impact of correlations be captured within such toy models?46,47,48.

To identify universal features resulted from purely electron-electron correlations and their evolution with doping, we systematically study the single-particle spectral function of the doped Hubbard model, with only t, \({t}^{\prime}\) and U and no other external ingredients. By calculating the spectral function at extremely fine doping levels over a wide range of electron and hole dopings, we expect to unbiasedly decipher the doping evolution of the dispersions, weights, and lineshapes of spectral features, and compare with ARPES experiments in cuprates. Though some of these properties have been studied previously at some discrete doping levels49,50, we find that the emergence of quasiparticles and their interplay with the polaronic Mott features cannot be fully addressed without reaching extreme limits of dopings. A detailed understanding of these spectral properties may provide insight on what aspects of experimental photoemission data can or cannot be well represented by the Hubbard model.

Results and discussion

The Hubbard model is presented in the Method section. Historically, a variety of numerical techniques have been used to investigate the single-particle spectrum of the Hubbard model, e.g., exact diagonalization51,52,53, quantum Monte Carlo54,55, density-matrix renormalization group56,57, dynamical mean-field theory58,59,60,61, CPT49,50,62,63,64 and others65,66,67,68,69. To investigate low-temperature spectral features with fine momentum resolution and continuous doping dependence, CPT with superclusters is the most suitable approach.

Overview

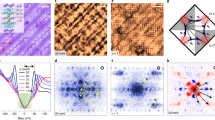

Fig. 1 shows the calculated spectral function A(k, ω) at two extreme dopings: undoped (half-filling) and heavily doped. At half-filling, a large Mott gap (~4t) separates the lower Hubbard band (LHB) and the upper Hubbard bands (UHB). Within each band, there are two main spectral features (see the markers in Fig. 1a): one at low binding energies, describable within a spin-polaron framework11,14; and a second at higher energies, which results from an effective intra-sublattice hopping70,71. A “waterfall”-like step connects the two features, constituting one of the critical spectral signatures of correlation effects.7,13,70,72 Throughout this paper, we refer to these single-particle these features that exist already at the half-filled Hubbard model as the Mott features. In the other extreme doping limit (see Fig. 1b, c), the spectrum resembles that of non-interacting electrons, although the Hubbard U remains unchanged. A quasiparticle dispersion across EF dominates the spectral function, with indiscernible residual spectral weight on the other side of the Mott gap. This feature, to which we refer as the quasiparticle, follows the tight-binding functional form of the bare band structure, but is subject to a doping-dependent bandwidth renormalization49,50,73.

Spectral function of the Hubbard model calculated using cluster perturbation theory (CPT): a for the half-filled Mott insulator and b, c for the 87.5% hole- and electron-doped system, respectively. The dotted line in b and c denotes the non-interacting tight-binding dispersion, while the horizontal dashed lines mark EF. The Brillouin zone (BZ) cartoon shows the spectral cut between the Γ, X, and M high-symmetry points for the square lattice. Labels in a denote the “Mott features”.

Density of states

Between these two limits, we first investigate the density of states (DOS) evolution with doping (see Fig. 2a–d). We see that a remnant Mott gap exists at all doping levels and well separates the UHB and LHB. Though it is somewhat expected in a single-band Hubbard model, we want to emphasize that the robustness of the charge-transfer gap in doped cuprates has bee recently confirmed through STM experiments74. Moreover, infinitesimal doping leads to the development of spectral weight at EF for both electron- and hole-doping. With increasing doping, the spectral weight transfer gradually depletes the upper (lower) Hubbard band, and the chemical potential smoothly evolves away from half-filling (with a finite linewidth, one can still define a EF at n = 1). In this process, the transferred spectral weight becomes energetically mixed with the lower (upper) Hubbard band upon doping, rather than forming an entirely separate in-gap state25,75.

a, d Evolution of the calculated density of states (DOS) with hole and electron doping, respectively. The green regions highlight the doping-induced states above (hole-doping) and below (electron-doping) EF. The gray dashed lines denote the DOS for the non-interacting model, and the brown shades indicate the Mott gap. b The dependence of EF on the electron density n, reflecting the Mott plateau. The solid (open) circles show results from calculations without (with) a supercluster construction. c The integrated weight of panels a and d. The doping-induced and remnant spectral weight in the lower Hubbard band (LHB) and the upper Hubbard bands (UHB) are plotted in green, red and blue, respectively. The solid brown curve denotes their separation at the gap center, while the dashed green curve denotes the separation between doping-induced states and the LHB (UHB), assuming the latter has equal weight with the UHB (LHB).

To quantify such spectral weight evolution, we integrate the three regions: residual LHB and UHB (red and blue) and the doping-induced states (green), respectively. Unlike the separations at EF in Fig. 2a, d, we further assume that the residual LHB (UHB) in a hole-doped (electron-doped) system carries the same spectral weight as the UHB (LHB) and, therefore, assign a small portion of spectral weight below (above) EF to the doping-induced states (see Fig. 2c). We believe this assignment gives a better characterization compared to previous studies using small-cluster Hubbard or charge-transfer models49,75,76,77,78,79,80, because we have considered that the doping-induced feature (i.e., quasiparticle) penetrates EF and coexists with the Mott features. As such, with the increasing doping, the rapid growth of it spectral weight involves contributions from both the LHB and UHB via doping. Our analysis shows that initially the spectral weight changes as ~2x (where x is the concentration of doped carriers), but is reduced to 0.84x starting from roughly optimal doping. This gradual change reflects the unraveling of electronic correlations upon doping.

Spectral function

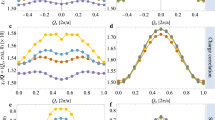

Taking a closer look in momentum space to identify where and how the quasiparticles emerge via A(k, ω), Fig. 3 shows the doping dependent single-particle spectra along high-symmetry cuts. In contrast to the back-bending spin-polaron at half-filling, doping immediately leads to the appearance of spectral weight near EF (see Fig. 3a), with a heavily renormalized quasiparticle dispersion consistent with ARPES experiments on the underdoped cuprates24,25,28,47. The spectral weight of this quasiparticle grows monotonically with doping: it gradually “fills-in” near the M-point for hole doping, and the Γ-point for electron doping. A clear suppression of the antinodal spectral weight at low hole doping reflects the pseudogap, while a similar suppression of the node at low electron doping indicates the hotspot (see Supplementary Note 1). The appearance of these two distinct phenomena suggests that the major normal-state quasiparticle features at optimal doping may also be qualitatively captured by a single-band Hubbard model.5,81,82 Upon further doping, the renormalization gradually decreases, and the quasiparticle dispersion smoothly evolves into the free dispersion shown in Fig. 1b, c.

a Energy distribution curves (EDCs) for calculated spectral functions with 1.4% hole doping. b False-color plot for the spectral function A(k, ω) near EF along high-symmetry cuts, as indicated by the inset, for a fixed energy window and various electron concentrations with hole doping. c, d Same as a, b but for electron doping instead. In a and c, the green arrows denote the quasiparticle features, while the red and blue arrows denote the remnant spin-polaron features at the lower- and upper-Hubbard band, respectively. In all panels, the gray dashed line denotes Fermi level.

The difference between the Hubbard model calculation and ARPES spectrum mainly lies in the lineshape near kF. In contrast to a broad peak describable by the strong polaronic dressing at half-filling and light doping25, the renormalized quasiparticle in Fig. 3 is always sharp near (π/2, π/2) for hole doping (also see the Supplementary Note 2). That means the linewidth change in the underdoped regime cannot be attributed simply to the quasiparticle dressed by spin excitations in the doped Hubbard model. Correlation-enhanced phonon polaronic dressing may be required to reproduce the experimental lineshape26. The omission of the phonon dressing also may relate to the shape of the chemical potential jump ~ t ~ 300meV in Fig. 2b for a small doping out of half-filling, which is observed smoother in cuprate experiments83.

Doping dependence of spectral weights

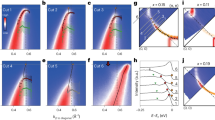

Besides the qualitative spectral shape, we perform quantitative analysis of the spectral weight doping evolution at two distinct momenta and within reprsentative energy ranges. We first focus on the M-point, where the quasiparticle is most separated from the higher-energy Mott features (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 3b). In Fig. 4a, we observe rapid growth in the spectral weight associated with the quasiparticle (green), overwhelming the remnants of the lower Hubbard band (red) at a moderate hole concentration. Residual spectral weight of the latter features gradually decreases with doping until their disappearance at ~20% doping (see Fig. 4b). The visibility of these Mott features in doped systems has two interesting implications. On one hand, the coupling between carriers and spin fluctuations is present even in a regime without long-range magnetic order, consistent with several recent experimental observations19,20,21,23. On the other hand, the eventual disappearance of these Mott features may account for the transition to a more metallic phase at ~20% doping in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x17,18 and YBa2Cu3O6+x48.

a Energy distribution curves at the M-point for different hole doping levels. The green shaded region highlights the growth of the quasiparticle, while red marks residual Mott features in the lower Hubbard band. b Integrated spectral weight of features in a. c A similar analysis performed in electron-doped systems at the Γ-point instead, where blue marks the corresponding integrated weight in the upper Hubbard bands.

A similar analysis for electron doping, now at the Γ-point, indicates substantial particle-hole asymmetry with respect to doping (see Fig. 4c). The Mott features persist until even higher doping on the electron-doped side. Although the finite cluster size of CPT calculations precludes definitive assessment of long-range order, the correlation effects at heavy doping suggest a substantial impact of spin correlations. This agrees with the recent discovery of Fermi surface reconstruction outside the AFM phase in Nd2−xCexCuO416. Here, the visibility of Mott features at higher doping (up to ~40%) than the hole-doped side reflects more robust magnetic correlations in the electron-doped Hubbard model84,85,86.

To verify the above dichotomy within occupied states measurable by ARPES experiments, we focus our attention on the spectrum near kF along the nodal direction, where the dispersion crosses EF. Comparing the spectral weight in two momentum-energy windows—one close to EF and a second at higher binding energy—we can quantitatively distinguish the evolution of the quasiparticle spectral weight from the Mott features (specifically spin-polaron in the calculation) at low doping. As shown in Fig. 5a, following a rapid exchange of spectral weight below 2% hole doping, both features begin to saturate and coexist (with comparable spectral intensities). We also observe consistent behavior in experimental spectra for the extremely underdoped regime of La2−xSrxCuO4 (see Fig. 5b–d). After immediate development of the quasiparticle feature at 1% doping, the spectral weight ratio between the quasiparticle and polaronic features saturates in the subsequent large range of doping. Such a saturation has been also observed in optimally doped HgBa2CuO4+δ87 and Nd2−xCexCuO416. This agreement confirms our theoretical prediction that strong correlations continue to play an essential role up to relatively high doping levels. (Note that the two integration windows have different areas: the upper one (red) covers (kF − 0.05Å, kF + 0.05Å) × (−0.05 eV, 0), while the lower one (blue) is (kF−0.23Å, kF + 0.07Å) × (−0.31eV, −0.29eV). Therefore, the ratio in Fig. 5d gives the trend for doping dependence instead of the absolute value of the quasiparticle weight).

a The spectral weight ratio between the lower and higher energy windows obtained from calculations (open circles) and experiments (solid squares). The shaded region denotes the antiferromagnetic phase in (La,Sr)2CuO4. b–d Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy experiments on underdoped (La,Sr)2CuO4 for half-filling, 1% and 12% doping near kF. The red and blue boxes in c denote the lower and higher energy windows near Fermi momentum kF, corresponding to the quasiparticle and polaronic feature, respectively. Their ratios correspond to the dots in a.

In contrast to the agreement of the spectral weight’s doping dependence, the numerically calculated (nodal) spectral features of the Hubbard model are sharper than those found in the ARPES experiment of cuprates (see the comparison between Figs. 3 and 5). While one culprit is the lack of the electron-phonon coupling in the calculations, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that the quasiparticle may become less coherent already within the Hubbard model—but only when explicitly calculated using far larger clusters (which is, as of now, unfeasible due to the exponential growth of the Hilbert space with the cluster size) [see the Methods section].

Conclusion

We have presented a comprehensive benchmark study of the single-particle spectral function of cuprates upon hole and electron doping, from the perspective of the single-band Hubbard model. We have analyzed and dissected the various features of the single-particle spectra, showing their distinct origins by carefully examining their doping dependences. Many of the conclusions drawn from the Hubbard model show good agreement with existing and here reported ARPES experiments. Starting from an extremely underdoped regime, doped carriers induce quasiparticle-like states near the Fermi level. Both the momentum-resolved calculations and ARPES experiments reveal that these itinerant states have no analog in the Mott insulating state at half-filling (i.e., the Mott gap, spin-polaron, and high-energy intra-sublattice features). Instead, an important finding of this work is that these emergent features coexist with the original Mott features in a wide range of doping. Though heavily renormalized with small spectral weight at low doping, this quasiparticle feature gradual emerges from the Mott feature at a rate roughly twice that of the doping. With heavy doping (~20% for hole-doping), the continued presence and electron-hole asymmetry of correlations are consistent with the observations in recent ARPES and RIXS experiments15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

From these aspects, the single-band Hubbard model seems to effectively capture the essence of the emergence of low energy quasiparticles, from the extremely underdoped regime to the overdoped regime. However, in contrast to these qualitative consistencies in spectral weight and dispersion, the almost doping-independent lineshape calculated from the Hubbard model cannot address the observations in parent compounds or lightly doped cuprates; the purely electronic Hubbard model also fails to reproduce the widely observed low-energy kinks in the quasiparticle bands37,38,39. Towards a more comprehensive picture, including lattice polaronic coupling provides another channel to destroy the quasiparticles’ coherence25, contributing to material-specific dependence in various cuprate families as well as other transition metal oxides.

Methods

Hubbard model

The Hamiltonian of the single-band Hubbard model is given by88,89

Here, \({c}_{{\bf{i}}\sigma }^{\dagger }\) (ciσ) and niσ denote the creation (annihilation) and density operators at site i of spin σ, respectively; U denotes the on-site Coulomb interaction; and tij encodes the electron hopping, restricted here to nearest-neighbors t〈ij〉 = t and next-nearest-neighbors \({t}_{\langle \langle {\bf{ij}}\rangle \rangle }={t}^{\prime}\). We chose parameters U = 8t and \({t}^{\prime}=-0.3t\), common for simulations of cuprates.

Single-particle spectral function and cluster perturbation theory

The single particle spectral function, which corresponds to the ARPES measurement, is defined as:

where \({c}_{{\bf{k}}\sigma }={\sum }_{{\bf{i}}}{c}_{{\bf{i}}\sigma }{e}^{-i{\bf{k}}\cdot {{\bf{r}}}_{{\bf{i}}}}/\sqrt{N}\) denotes the electron annihilation operator at momentum space, \(\left|G\right\rangle\) is the ground state with energy EG. We choose a Lorentzian energy broadening of δ = 0.15t throughout this paper.

The idea of cluster perturbation theory (CPT) was invented by Sénéchal et al.63,64 and was demonstrated to be an efficient approach to estimate the A(k, ω) of strongly correlated systems at zero temperature. For completeness, we briefly reiterate the CPT method here, while the readers should refer to Ref. 64 for details. Assuming one divides the infinite plane into clusters, the Hamiltonian can be split into \({\mathcal{H}}={{\mathcal{H}}}_{c}+{{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{int}}}\). Here \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{c}\) contains the (open-boundary) intra-cluster operators, while \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{int}}}\) contains the operators with inter-cluster indices (hopping terms for the Hubbard model). Then one can use exact diagonalization to precisely solve the Green’s function Gc(ω) associated with the intra-cluster Hamiltonian \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{c}\). Here, we use the parallel Arnoldi method and the Paradeisos algorithm to determine the equilibrium ground-state wavefunction.90,91

The CPT method then estimate the Green’s function of the infinite plane by treating \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{int}}}\) perturbatively, giving

where \(V({\bf{k}})={\sum }_{{\bf{R}}}{{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{int}}}{e}^{i{\bf{k}}\cdot {\bf{R}}}\) is the inter-cluster interactions projected to the intra-cluster coordinates. Then taking the long-wavelength limit, we obtain

where a, b are intra-cluster site indices. Although CPT gives corrections to the small-cluster ED calculations and reduces the finite-size effect, the finite-size effect does not entirely disappear in the CPT calculations63,64. With an increase of the system size, the number of poles of the Gc(ω) grows (see Fig. 2 in ref. 63).

The CPT method can be further generalized into superclusters, giving access to any rational doping values. Denoting the Green’s function of a (disconnected) supercluster consisting of M clusters as \({G}_{0}={\oplus }_{m}^{M}{G}_{c}^{(m)}\), where \({G}_{c}^{(m)}\) is the intra-cluster Green’s function of the m-th cluster. Note that these M clusters can be filled by different integer numbers, leading to an averaged rational filling in the supercluster. Then following the CPT philosophy, one can first include the inter-cluster perturbation inside the supercluster, giving

where \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{int}}}^{(ic)}\) is the inter-cluster Hamiltonian terms within the supercluster. The CPT correlation of the supercluster Green’s function then gives

Similar to Eq. (3), the Vsc(k) is the inter-supercluster hopping. In the calculations of the main text, we evaluate the 4 × 4 cluster spectral function by an exact solver and 8 × 8 or 12 × 12 by a supercluster solver.64

The density of states (DOS) is calculated through the integration of A(k, ω) over the first Brillium zone:

The Fermi level is then determined by the equality DOS(EF) = n.

Experimental details

High-quality single crystals of La2−xSrxCuO4 (LSCO) are synthesized with traveling solvent floating zone method, and subsequently cut into ~1 × 1 × 0.5 mm3 pieces along the crystal axes. They are then glued to oxygen-free copper sample holders with alternating layers of conductive silver epoxy and Torr seal resin. Ceramic top posts are then glued to the surface of the single crystals, only to be cleaved under ultrahigh vacuum to expose fresh surfaces for photoemission measurements.

Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy on ten different dopings of LSCO is performed at beamline 10.0.1 in the Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and beamline 5-4 at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource at SLAC National Laboratory. The vacuum is kept at better than 5 × 10−11 Torr throughout the experiments. 55 eV and 20 eV photons are used with the linear polarization parallel to the diagonal Cu-Cu (nodal) direction. All data shown here are collected at 10-15 K except for x = 0 sample, which is measured at 50 K to mitigate static charging effect.

Data availability

The numerical and experimental data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The relevant scripts of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wen, X.-G. & Lee, P. A. Theory of underdoped cuprates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 503–506 (1996).

Lee, P. A., Nagaosa, N. & Wen, X.-G. Doping a mott insulator: physics of high-temperature superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 17 (2006).

Stephan, W. & Horsch, P. Fermi surface and dynamics of the t-J model at moderate doping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 2258–2261 (1991).

Dagotto, E. Correlated electrons in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 763–840 (1994).

Damascelli, A., Hussain, Z. & Shen, Z.-X. Angle-resolved photoemission studies of the cuprate superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 473–541 (2003).

Zhang, F. & Rice, T. Effective hamiltonian for the superconducting Cu oxides. Phys. Rev. B 37, 3759 (1988).

Ronning, F. et al. Anomalous high-energy dispersion in angle-resolved photoemission spectra from the insulating cuprate Ca2CuO2Cl2. Phys. Rev. B 71, 094518 (2005).

Meevasana, W. et al. Hierarchy of multiple many-body interaction scales in high-temperature superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 75, 174506 (2007).

Valla, T. et al. High-energy kink observed in the electron dispersion of high-temperature cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 167003 (2007).

Xie, B. et al. High-energy scale revival and giant kink in the dispersion of a cuprate superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 147001 (2007).

Martinez, G. & Horsch, P. Spin polarons in the t-J model. Phys. Rev. B 44, 317 (1991).

Bała, J., Oleś, A. & Zaanen, J. Spin polarons in the t-t\({\,}^{\prime}\)'-J model. Phys. Rev. B 52, 4597–4606 (1995).

Macridin, A., Jarrell, M., Maier, T. & Scalapino, D. High-energy kink in the single-particle spectra of the two-dimensional hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 237001 (2007).

Manousakis, E. String excitations of a hole in a quantum antiferromagnet and photoelectron spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 75, 035106 (2007).

Graf, J. et al. Universal high energy anomaly in the angle-resolved photoemission spectra of high temperature superconductors: possible evidence of spinon and holon branches. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 067004 (2007).

He, J. et al. Fermi surface reconstruction in electron-doped cuprates without antiferromagnetic long-range order. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 3449–3453 (2019).

He, Y. et al. Rapid change of superconductivity and electron-phonon coupling through critical doping in bi-2212. Science 362, 62–65 (2018).

Chen, S.-D. et al. Incoherent strange metal sharply bounded by a critical doping in Bi2212. Science 366, 1099–1102 (2019).

Le Tacon, M. et al. Intense paramagnon excitations in a large family of high-temperature superconductors. Nat. Phys. 7, 725–730 (2011).

Dean, M. et al. Persistence of magnetic excitations in La2-xSrxCuO4 from the undoped insulator to the heavily overdoped non-superconducting metal. Nat. Mater. 12, 1019–1023 (2013).

Dean, M. et al. High-energy magnetic excitations in the cuprate superconductor Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ: towards a unified description of its electronic and magnetic degrees of freedom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 147001 (2013).

Lee, W. et al. Asymmetry of collective excitations in electron-and hole-doped cuprate superconductors. Nat. Phys. 10, 883 (2014).

Ishii, K. et al. High-energy spin and charge excitations in electron-doped copper oxide superconductors. Nat. Commun. 5, 3714 (2014).

Shen, K. M. et al. Nodal quasiparticles and antinodal charge ordering in Ca2-xNaxCuO2Cl2. Science 307, 901–904 (2005).

Shen, K. et al. Missing quasiparticles and the chemical potential puzzle in the doping evolution of the cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 267002 (2004).

Mishchenko, A. & Nagaosa, N. Electron-phonon coupling and a polaron in the t-J model: from the weak to the strong coupling regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 036402 (2004).

Mishchenko, A. & Nagaosa, N. Numerical study of the isotope effect in underdoped high-temperature superconductors: calculation of the angle-resolved photoemission spectra. Phys. Rev. B 73, 092502 (2006).

Shen, K. et al. Angle-resolved photoemission studies of lattice polaron formation in the cuprate Ca2CuO2Cl2. Phys. Rev. B 75, 075115 (2007).

Rösch, O. et al. Polaronic behavior of undoped high-Tc cuprate superconductors from angle-resolved photoemission spectra. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 227002 (2005).

Slezak, C., Macridin, A., Sawatzky, G., Jarrell, M. & Maier, T. A. Spectral properties of Holstein and breathing polarons. Phys. Rev. B 73, 205122 (2006).

Gunnarsson, O. & Rösch, O. Electron-phonon coupling in the self-consistent Born approximation of the t-J model. Phys. Rev. B 73, 174521 (2006).

Tranquada, J. M., Buttrey, D., Sachan, V. & Lorenzo, J. Simultaneous ordering of holes and spins in La2NiO4.125. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1003 (1994).

Ramirez, A. et al. Thermodynamic and electron diffraction signatures of charge and spin ordering in La1-xCaxMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 3188 (1996).

Cwik, M. et al. Magnetic correlations in La2-xSrxCoO4 studied by neutron scattering: possible evidence for stripe phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 057201 (2009).

Ulbrich, H. & Braden, M. Neutron scattering studies on stripe phases in non-cuprate materials. Phys. C. 481, 31–45 (2012).

Tranquada, J. M. Spins, stripes, and superconductivity in hole-doped cuprates. In AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 1550, 114-187 (AIP, 2013).

Bogdanov, P. et al. Evidence for an energy scale for quasiparticle dispersion in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2581 (2000).

Lanzara, A. et al. Evidence for ubiquitous strong electron–phonon coupling in high-temperature superconductors. Nature 412, 510 (2001).

Zhou, X. J. et al. High-temperature superconductors: universal nodal Fermi velocity. Nature 423, 398 (2003).

Cuk, T. et al. Coupling of the B1g phonon to the antinodal electronic states of Bi2Sr2Ca0.92Y0.08Cu2O8+δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 117003 (2004).

Johnston, S. et al. Evidence for the importance of extended Coulomb interactions and forward scattering in cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 166404 (2012).

Ohta, Y., Tohyama, T. & Maekawa, S. Apex oxygen and critical temperature in copper oxide superconductors: Universal correlation with the stability of local singlets. Phys. Rev. B 43, 2968 (1991).

Peng, Y. et al. Influence of apical oxygen on the extent of in-plane exchange interaction in cuprate superconductors. Nat. Phys. 13, 1201 (2017).

Slezak, J. et al. Imaging the impact on cuprate superconductivity of varying the interatomic distances within individual crystal unit cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3203–3208 (2008).

Sakakibara, H., Usui, H., Kuroki, K., Arita, R. & Aoki, H. Origin of the material dependence of Tc in the single-layered cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 85, 064501 (2012).

Kordyuk, A. et al. Bare electron dispersion from experiment: Self-consistent self-energy analysis of photoemission data. Phys. Rev. B 71, 214513 (2005).

Yoshida, T. et al. Systematic doping evolution of the underlying Fermi surface of La2-xSrxCuO4. Phys. Rev. B 74, 224510 (2006).

Fournier, D. et al. Loss of nodal quasiparticle integrity in underdoped YBa2Cu3O6+x. Nat. Phys. 6, 905 (2010).

Kohno, M. Mott transition in the two-dimensional Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 076401 (2012).

Kohno, M. Spectral properties near the mott transition in the two-dimensional Hubbard model with next-nearest-neighbor hopping. Phys. Rev. B 90, 035111 (2014).

Li, Q., Callaway, J. & Tan, L. Spectral function in the two-dimensional Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 44, 10256–10269 (1991).

Dagotto, E., Ortolani, F. & Scalapino, D. Single-particle spectral weight of a two-dimensional Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 46, 3183–3186 (1992).

Imada, M., Fujimori, A. & Tokura, Y. Metal-insulator transitions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 1039–1263 (1998).

White, S. et al. Numerical study of the two-dimensional Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 40, 506 (1989).

Foulkes, W., Mitas, L., Needs, R. & Rajagopal, G. Quantum Monte Carlo simulations of solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 33 (2001).

White, S. R. Density matrix formulation for quantum renormalization groups. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2863 (1992).

Schollwöck, U. The density-matrix renormalization group. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 259 (2005).

Kancharla, S. et al. Anomalous superconductivity and its competition with antiferromagnetism in doped Mott insulators. Phys. Rev. B 77, 184516 (2008).

Weber, C., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Strength of correlations in electron-and hole-doped cuprates. Nat. Phys. 6, 574–578 (2010).

Gull, E., Parcollet, O. & Millis, A. J. Superconductivity and the pseudogap in the two-dimensional Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 216405 (2013).

Sakai, S., Motome, Y. & Imada, M. Evolution of electronic structure of doped mott insulators: reconstruction of poles and zeros of Greens function. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 056404 (2009).

Gros, C. & Valenti, R. Cluster expansion for the self-energy: a simple many-body method for interpreting the photoemission spectra of correlated Fermi systems. Phys. Rev. B 48, 418 (1993).

Sénéchal, D., Perez, D. & Pioro-Ladrière, M. Spectral weight of the Hubbard model through cluster perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 522–525 (2000).

Sénéchal, D., Perez, D. & Plouffe, D. Cluster perturbation theory for Hubbard models. Phys. Rev. B 66, 075129 (2002).

Yuan, Q., Yuan, F. & Ting, C. Doping dependence of the electron-doped cuprate superconductors from the antiferromagnetic properties of the Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 72, 054504 (2005).

Arrigoni, E., Aichhorn, M., Daghofer, M. & Hanke, W. Phase diagram and single-particle spectrum of CuO2 high-Tc layers: variational cluster approach to the three-band Hubbard model. N. J. Phys. 11, 055066 (2009).

Han, X.-J. et al. Charge dynamics of the antiferromagnetically ordered Mott insulator. N. J. Phys. 18, 103004 (2016).

Hettler, M., Mukherjee, M., Jarrell, M. & Krishnamurthy, H. Dynamical cluster approximation: Nonlocal dynamics of correlated electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 61, 12739 (2000).

Potthoff, M., Aichhorn, M. & Dahnken, C. Variational cluster approach to correlated electron systems in low dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 206402 (2003).

Wang, Y. et al. Origin of strong dispersion in Hubbard insulators. Phys. Rev. B 92, 075119 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Erratum: origin of strong dispersion in hubbard insulators [Phys. Rev. B 92, 075119 (2015)]. Phys. Rev. B 97, 199903 (2018).

Moritz, B. et al. Effect of strong correlations on the high energy anomaly in hole- and electron-doped high-Tc superconductors. New J. Phys. 11, 093020 (2009).

Wang, Y., Moritz, B., Chen, C.-C., Devereaux, T. P. & Wohlfeld, K. Influence of magnetism and correlation on the spectral properties of doped Mott insulators. Phys. Rev. B 97, 115120 (2018).

Zhong, Y. et al. Direct visualization of ambipolar mott transition in cuprate CuO2 planes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 077002 (2020).

Imada, M., Fujimori, A. & Tokura, Y. Metal-insulator transitions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 1039 (1998).

Eskes, H., Meinders, M. & Sawatzky, G. Anomalous transfer of spectral weight in doped strongly correlated systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 1035 (1991).

Dagotto, E., Moreo, A., Ortolani, F., Riera, J. & Scalapino, D. Density of states of doped Hubbard clusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 1918 (1991).

Chen, C. et al. Electronic states in La2-xSrxCuO4+δ probed by soft-x-ray absorption. Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 104 (1991).

Liebsch, A. Spectral weight of doping-induced states in the two-dimensional Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 81, 235133 (2010).

Phillips, P. Colloquium: Identifying the propagating charge modes in doped Mott insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1719 (2010).

Armitage, N., Fournier, P. & Greene, R. Progress and perspectives on electron-doped cuprates. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2421 (2010).

Sénéchal, D. & Tremblay, A.-M. Hot spots and pseudogaps for hole-and electron-doped high-temperature superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 126401 (2004).

Yagi, H. et al. Chemical potential shift in lightly doped to optimally doped Ca2-xNaxCuO2Cl2. Phys. Rev. B 73, 172503 (2006).

Tohyama, T. Asymmetry of the electronic states in hole-and electron-doped cuprates: exact diagonalization study of the t- t'- t''- j model. Phys. Rev. B 70, 174517 (2004).

Moritz, B. et al. Investigation of particle-hole asymmetry in the cuprates via electronic Raman scattering. Phys. Rev. B 84, 235114 (2011).

Wang, Y., Jia, C., Moritz, B. & Devereaux, T. P. Real-space visualization of remnant Mott gap and magnon excitations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 156402 (2014).

Vishik, I. et al. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy study of HgBa2CuO4+δ. Phys. Rev. B 89, 195141 (2014).

Zhang, F. & Rice, T. Effective Hamiltonian for the superconducting Cu oxides. Phys. Rev. B 37, 3759–3761 (1988).

Eskes, H. & Sawatzky, G. Tendency towards local spin compensation of holes in the high-Tc copper compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 1415–1418 (1988).

Lehoucq, R. B., Sorensen, D. C. & Yang, C. ARPACK Users’ Guide: Solution of Large-Scale Eigenvalue Problems with Implicitly Restarted Arnoldi Methods (Siam, 1998).

Jia, C., Wang, Y., Mendl, C., Moritz, B. & Devereaux, T. Paradeisos: a perfect hashing algorithm for many-body eigenvalue problems. Comput. Phys. Commun. 224, 81 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering, under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. Y.W. acknowledges the National Science Foundation (NSF) through grant No. DMR-2038011. K.W. acknowledges support from the Polish National Science Center (NCN) under Project No. 2016/22/E/ST3/00560 and 2016/23/B/ST3/00839. Y.H. acknowledges support from the Miller Institute for Basic Research in Science. E.W.H. was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation EPiQS Initiative through the grant GBMF 4305 and GBMF 8691. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The ARPES experiments were performed at the Advanced Light Source (ALS), which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, and at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) which is supported by the DOE, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering, under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. and K.W. performed the calculations. Y.H. carried out the ARPES measurements with support from M.H., D.L. and S.M. S.K. grew the single crystals used in the experiment. Y.W. and Y.H. performed the data analysis. B.M., Z.-X.S. and T.P.D. provided guidance to the designed research. Y.W., Y.H. and K.W. wrote the paper with the help from E.W.H., B.M., C.J. and T.P.D.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., He, Y., Wohlfeld, K. et al. Emergence of quasiparticles in a doped Mott insulator. Commun Phys 3, 210 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00480-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00480-5

This article is cited by

-

Unveiling phase diagram of the lightly doped high-Tc cuprate superconductors with disorder removed

Nature Communications (2023)

-

High harmonic generation in two-dimensional Mott insulators

npj Quantum Materials (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.