Abstract

The frequency stability of many optical atomic clocks is limited by the coherence of their local oscillator. Here, we present a measurement protocol that overcomes the laser coherence limit. It relies on engineered dynamical decoupling of laser phase noise and near-synchronous interrogation of two clocks. One clock coarsely tracks the laser phase using dynamical decoupling; the other refines this estimate using a high-resolution phase measurement. While the former needs to have a high signal-to-noise ratio, the latter clock may operate with any number of particles. The protocol effectively enables minute-long Ramsey interrogation for coherence times of few seconds as provided by the current best ultrastable laser systems. We demonstrate implementation of the protocol in a realistic proof-of-principle experiment, where we interrogate for 0.5 s at a laser coherence time of 77 ms. Here, a single lattice clock is used to emulate synchronous interrogation of two separate clocks in the presence of artificial laser frequency noise. We discuss the frequency instability of a single-ion clock that would result from using the protocol for stabilisation, under these conditions and for minute-long interrogation, and find expected instabilities of σy(τ) = 8 × 10−16(τ/s)−1/2 and σy(τ) = 5 × 10−17(τ/s)−1/2, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The progress of optical clocks has enabled a multitude of applications that range from testing fundamental symmetries underlying relativity1,2 and searching for physics beyond the standard model3,4,5, including dark matter6,7,8,9,10, to measuring geopotential differences11,12 and the proposed use for gravitational wave detection13. Since lower frequency instability of a clock reduces the time required to perform measurements with a given precision, it benefits applications in general and those where time-dependent effects are measured, including transient changes of fundamental constants10, in particular. Therefore, the advancement of ultrastable lasers14,15 and other techniques to reduce measurement instability16,17,18,19,20 continue to be a focus of research.

The frequency stability of optical clocks is limited by quantum projection noise21 (QPN) as well as aliased laser frequency noise due to non-continuous observation, which is known as the Dick effect22,23. The contribution of the latter depends intricately on the noise spectrum of the laser and the parameters of clock operation. It can be minimised by using Ramsey spectroscopy, which best recovers the unweighted mean laser frequency during the interrogation time Ti, in combination with little or no dead time. Ultimately, QPN limits the instability of an atomic clock, given by the Allan deviation σy, to the standard quantum limit

if N uncorrelated atoms or ions are interrogated, where ν0 is the frequency of the clock transition, Tc the total cycle time, and τ the averaging time24.

A clock’s frequency instability is thus minimised by using the longest possible interrogation time. It is, in fact, the only way to improve the frequency instability for single-ion clocks, which are limited by their significant QPN (N = 1) through Eq. (1). The situation is more complex in optical lattice clocks, which benefit from their lower projection noise (N ≫ 1). Their frequency instability can be improved by reducing projection noise, including the use of spin squeezing25,26, and by the rejection of the Dick effect using techniques such as synchronous17 or dead time-free interrogation19,20. These are complementary to and can be combined with maximising interrogation time to achieve the best possible frequency stability. However, the coherence of even the most stable lasers15 limits interrogation times well short of the excited-state lifetimes of the most promising clock species1,27,28,29 and of ultranarrow transitions in several species of highly charged ions30,31.

For Ramsey interrogation, the excitation probability pe depends sinusoidally on the phase difference ϕ = 2πTiΔν that accumulates between the laser light field and the atomic oscillator during interrogation, where Δν is the corresponding average frequency offset. Thus, phase deviations due to laser noise can only be traced unambiguously within \(\left|\phi \right|\le \pi /2\). In analogy to ref. 15, we define the coherence time Tco by requiring that the laser phase stay in this invertible range in 99% of all cases. This corresponds to a coherence time of about Tco = 5.5 s at a frequency of 194 THz for the best state-of-the-art lasers15, whereas excited-state lifetimes of clock transitions can be much longer, e.g. from 20.6 s in the Al+ ion32 through several minutes in neutral strontium33 to several years for the electric octupole transition in the Yb+ ion34. Therefore, operating a clock beyond the laser coherence limit is a highly interesting route to enhancing frequency stability.

Dynamical decoupling methods35 can prevent decoherence from a variety of noise sources, e.g. spin-echo methods suppress inhomogeneous broadening36. However, perfect decoupling of laser frequency noise is not useful for operation of a clock, which relies on tracing the mean laser frequency with respect to the atomic resonance.

Here, we present a coherent multi-pulse interrogation scheme that partially decouples laser noise in a well-controlled fashion, with similarities to spin-echo sequences, and a compound clock system that applies this dynamical decoupling scheme in one clock to improve the performance of another clock. We demonstrate phase measurement by such a system well beyond the laser coherence limit in a proof-of-principle experiment, which uses artificially imprinted laser frequency noise and emulates synchronous operation of the two clocks by consecutive measurements in a single optical lattice clock. Finally, we analyse the expected improvement in clock performance for single-ion clocks with suitably narrow transitions. We find that frequency instability improves with interrogation time according to Eq. (1), which reduces the averaging time required to realise a given measurement precision by more than an order of magnitude.

Results and discussion

Dynamical decoupling of laser noise

Figure 1 and Supplementary Movie 1 illustrate a multi-pulse interrogation scheme, which dynamically decouples the atomic superposition state from laser phase noise to a controllable degree. A variable number M of ‘flip’ pulses with pulse area π − ϵ divides the free-evolution time into short periods of durations Td or Td/2. Each pulse maps the phase accumulated during free-evolution onto atomic state population. An example of the resulting line shape is shown in Fig. 2. In comparison to Ramsey interrogation, it trades reduced discriminator sensitivity for a much wider range over which the mean laser frequency can be traced.

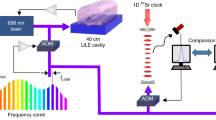

a Schematic setup of a compound clock for operation beyond the laser coherence limit. The two clocks share a common local oscillator (LO) that is pre-stabilised to an ultrastable cavity. The frequency stability of the LO is transferred to interrogation lasers, e.g. by a frequency comb (FC). Using the spectroscopic sequences shown in b, clock 1 provides a coarse estimate (ϕ1) of the laser phase deviation to clock 2, which then refines this measurement. Their combined measured phase deviation (ϕtot) feeds back into a frequency shifter (Δν) to stabilise the LO frequency. Note that the measured phase and frequency deviations need to be scaled by the frequency ratio when transferred to a clock or LO operating at a different frequency, which has been omitted here for the sake of simplicity. b Pulse sequences of clocks 1 and 2 as a function of time t (example). After an initial π/2 excitation pulse (red), the interrogation sequence of clock 1 interleaves free-evolution times of duration Td or Td/2 (light grey) and ‘flip’ pulses (orange) of pulse area π − ϵ and phase φ = ±π/2 with respect to the initial pulse. It ends with a pulse of area ϵ/2 (magenta) and state read-out (blue). Clock 2 uses a two-pulse Ramsey sequence. It receives laser phase information (ϕ1) from clock 1 in time to adjust the phase of the second π/2 pulse such that the fringe centre is shifted to maximise the signal slope. The delay \({T}_{{\mathrm{i}}}-{T}_{{\mathrm{i}}}^{\prime}\) must be kept short to avoid excess phase noise (see “Methods” section). c–e Evolution of the atomic state in clock 1 on the Bloch sphere for constant laser detuning at times t1 through t3, as marked in b (example). g and e indicate the ground and excited state of the clock transition, respectively. After accumulating phase during the first dark time Td/2 (c, blue), a flip pulse nearly reverses this precession of the Bloch vector and maps it onto a small change of excitation probability (c, red). The process is repeated twice with dark time Td (d and e, red). Finally, another free-evolution time Td/2 (e, light red) and the final laser pulse with area ϵ/2 (e, green) are applied.

The spectroscopy signal of clock 1 is shown as a function of laser detuning (for M = 6, ϵ = 0.08 π, Td = 40 ms, and a π-pulse duration Tπ = 1 ms). The line shape expected from theory in the absence of frequency noise (solid line) features a broad central fringe as well as a complex structure far off resonance. Measurements using our strontium lattice clock without artificial noise (circles) reproduce this line shape very well. Deviations can be attributed to limited contrast (around 90%) and fluctuations of laser intensity. The central fringe covers about 25 Hz, whereas the central fringe of Ramsey spectroscopy covers only about 2 Hz at the same interrogation time (Ti ≈ 0.25 s).

The compound clock consists of two clock packages that are interrogated nearly synchronously (Fig. 1): one provides a coarse estimate ϕ1 of the atom–laser phase deviation ϕ using the above scheme (clock 1), the other refines this measurement using Ramsey spectroscopy (clock 2), providing a correction ϕ2. Their combined phase measurement ϕtot = ϕ1 + ϕ2 traces the laser phase deviation ϕ for interrogation times Ti well beyond the laser coherence time Tco and with the full precision of Ramsey spectroscopy. The compound system thus achieves much better frequency stability than a comparable stand-alone clock, which is limited to Ti < Tco (Eq. (1)).

The interrogation sequence of clock 1 is tailored to the specific laser noise spectrum of the local oscillator and to the interrogation time. Using the number of flip pulses M and pulse defect ϵ, decoupling is adjusted such that the central fringe of the resulting line shape covers most of the laser’s phase excursions. Longer interrogation times Ti also require a larger number of flip pulses M, to keep the dark time Td ≈ Ti/M below the laser coherence limit. On the other hand, the discriminator slope of clock 1 must be steep enough to keep its absolute phase measurement error ∣Δϕ1∣ below π/2 in most cases. Within this invertible range, clock 2 is able to cancel Δϕ1 through its own measurement. Otherwise, a residual error remains in the final phase measurement (see “Methods” section), which may decrease the frequency stability of the compound clock. Maximising the interrogation time hence requires minimising the noise of clock 1. Optical lattice clocks are ideal candidates for this role due to their intrinsically low QPN. In contrast, clock 2 may well be a clock with a low signal-to-noise ratio, e.g. a single-ion clock. Finally, laser frequency noise contributes to the phase error in clock 1 through imperfections of the dynamical decoupling, which are similar to the well-known Dick effect22,23 (see “Methods” section). They are caused by the increased frequency sensitivity during the flip pulses, as shown in Fig. 3a. Their effect can be minimised by using as few flip pulses as possible and by decreasing their duration. Therefore, the maximum interrogation time Ti of the compound clock results mostly from a trade-off between technical limitations, such as the number of atoms of clock 1 or the available interrogation laser power.

a Frequency sensitivity g(t) of regular Ramsey spectroscopy22,23 (red line) and of the decoupled protocol (blue line). The increased sensitivity of the latter during each of the M = 16 flip pulses gives rise to imperfections of the dynamical decoupling (see main text and “Methods”). b Line shape of Ramsey spectroscopy (red line) and the decoupled protocol (blue line), scaled to a contrast of 0.75. The signals observed while scanning the laser across resonance in the absence of artificial frequency noise are shown for comparison (red diamonds, blue circles). Note that the Ramsey scan (red diamonds) was recorded for a slightly different dark time (500 ms) than used in the experiment. c Single-sided power spectral density (PSD) Sy(f) of the artificial laser noise imprinted onto the interrogation laser (blue line). The phase noise of our interrogation laser system as reported in ref. 15 is shown schematically for comparison (green line). d Distributions of final phase deviations due to artificial frequency noise (blue) and intrinsic laser noise (green) after the interrogation time.

Experiment

We perform a proof-of-principle experiment to demonstrate the compound clock scheme, using a state-of-the-art interrogation laser system15 and a strontium optical lattice clock37 (see “Methods” section for further details). Its goal is to characterise the quality of phase reconstruction for a series of known phase deviations, which are generated by imprinting artificial frequency noise onto the interrogation laser. Since this process is reproducible and the undisturbed laser’s frequency is highly stable, we use two consecutive interrogations of a single lattice clock to emulate synchronous operation of clocks 1 and 2 (see “Methods” section). It is preferable to use a lattice clock with low QPN as clock 2 for characterisation. The reduced coherence time of the laser, which results from the artificial noise, also minimises the effect of technical limitations such as nonlinear frequency drift of the laser and atomic decoherence. We do not implement feedback to the local oscillator (Fig. 1), to keep the measurements independent. However, we later use the recorded data to estimate the frequency instability of a compound clock using a single-ion clock. A direct demonstration, e.g. interrogating a lattice clock and a single-ion clock beyond the coherence time of the undisturbed interrogation laser, is beyond the scope of this article for technical and practical reasons.

The experiment is summarised in Fig. 3a–d. We use a noise spectrum (Fig. 3c and “Methods”) with a coherence time Tco = 77 ms for Ramsey interrogation and an interrogation time Ti ≈ 495 ms. At a root mean square (RMS) value of about σϕ = 0.7 π, the laser phase deviation ϕ during Ti thus exceeds the invertible range of Ramsey spectroscopy half of the time (\(P(\left|\Delta \phi \right|\;> \;\pi /2)=0.5\)). In our experiment, it covers nearly the entire interval \(\left[-\frac{5}{2}\pi ,\frac{5}{2}\pi \right]\), i.e. five Ramsey fringes.

Figure 4a–c shows the measured phase errors Δϕ1 of clock 1 and Δϕtot of the compound clock, i.e. including the measurement by clock 2, as a function of the phase deviations ϕ0 imprinted artificially onto the laser (ϕ ≈ ϕ0). The dynamical decoupling scheme works well across the entire range of phase deviations and with only a few gross phase reconstruction errors. Clock 1 determines the fringe observed by clock 2 correctly with probability P(∣Δϕ1∣ ≤ π/2) = 95.3(7)%. As seen in the figure, the phase errors of the compound clock are reduced further by the measurement of clock 2; we find P(∣Δϕtot∣ ≤ π/2) = 99.0(3)% for the full measurement. This proof-of-principle experiment thus demonstrates that the compound clock can be interrogated well beyond the laser coherence time (Ti/Tco ≈ 6.4).

a Phase measurement errors Δϕ1 of clock 1 only (blue circles) and Δϕtot of the full compound clock (red circles) in our proof-of-principle experiment, for K = 1093 unique samples of artificial laser frequency noise. ϕ0 is the phase excursion imprinted onto the interrogation laser for each sample. The grey shaded area represents the range of phase errors by clock 1 that can be fully compensated by the measurement of clock 2 (i.e. for which fringe assignment in clock 2 is correct, see main text and “Methods”). b Histogram of the phase measurement errors of clock 1 (blue) and of the compound clock (red). The grey shaded area represents the same range of phase errors as in a. c Histogram of the imprinted laser phase deviations for comparison.

In an additional measurement, we increase the power spectral density of the artificial flicker frequency noise by a factor of 2.25, which reduces the coherence time of the laser to Tco = 56 ms, but leave the other parameters unchanged. We observe a slightly reduced performance of the compound clock, P(∣Δϕtot∣ ≤ π/2) = 93.1(8)%, in this case.

Phase measurement errors

The frequency instability of the compound clock benefits from its increased interrogation time and duty cycle, as the contributions from QPN, the Dick effect, and other noise sources decrease. However, phase measurement errors Δϕ1 by clock 1 exceeding ±π/2 cause incorrect fringe assignment in clock 2 and prevent the compound clock from measuring the phase correctly (see “Methods” section). These errors hence give rise to an additional instability contribution, which needs to be taken into account to assess the benefits of using a compound clock. In our proof-of-principle experiment, a RMS phase error \({\sigma }_{{\phi }_{1}}\) by clock 1 of about 0.14 π is expected, mainly from dynamical decoupling imperfections (see “Methods” section). This would make incorrect fringe assignment highly improbable. Experimentally, we observe a broader distribution of errors in clock 1 (Fig. 4a, b), which we take into account when estimating the instability of a compound clock in this situation. The bulk of the measurement errors are described well by a normal distribution with a standard deviation of about σb = 0.24 π. Since we observe similar phase errors even without artificial laser noise, we attribute the difference to technical imperfections of the pulse sequence like power fluctuations. Moreover, large phase errors occur more frequently (\(P(\left|\Delta {\phi }_{1}\right|\;> \; 3{\sigma }_{{\rm{b}}})=1.1(3)\times 1{0}^{-2}\)) than expected for that normal distribution. Such outliers may be caused by particular features of a phase trajectory that cause a nonlinear response, e.g. precession of the Bloch vector in clock 1 by ∣ϕ∣ ⪆ π/2 during a dark time (cf. the results from the measurement with reduced coherence time). Even a few outliers may substantially affect the compound clock’s frequency instability because they can lead to large phase errors ∣Δϕtot∣ ⪆ π/2 (see “Methods” section). We account for the outliers by adding a uniform pedestal to the normal distribution. The pedestal is assigned a width of L = 2.5 π, such that it covers the actual one with 68% confidence, and an integrated weight η = 0.02, which reproduces the observed rate of outliers on average. The combined distribution reproduces the observed RMS phase error of clock 1 (\({\sigma }_{{\phi }_{1}}=0.25\ \pi\)) well. It maps to a contribution of about 0.10π to the RMS phase error \({\sigma }_{{\phi }_{{\rm{tot}}}}\) of the compound clock (see “Methods” section and Fig. 5). Finally, noise from clock 2 itself causes additional phase errors. It broadens the Dirac delta function at zero phase error shown in Fig. 5, which contains the bulk of the measurements, to a finite width. We estimate this width from the observed error distribution of the compound clock (Fig. 4b) and find a value of 0.07π, which we attribute mostly to residual frequency offsets of the undisturbed interrogation laser from resonance. The sum of these two error contributions reproduces the observed overall RMS phase error \({\sigma }_{{\phi }_{{\rm{tot}}}}=0.12\ \pi\) of the compound clock.

Phase errors from clock 1 are corrected using the measurement of clock 2. The resulting distribution of residual phase errors in the compound clock is estimated from that observed in clock 1: a Excitation probability pe in clock 2 as a function of the phase error Δϕ1 introduced by clock 1. b Probability distribution of phase errors Δϕ1 from clock 1, using the model discussed in the main text. c Probability distribution of residual phase errors Δϕtot of the compound clock, i.e. after correction by clock 2. Colour-coding illustrates which intervals of phase errors in b and c correspond to which fringe in a. Grey lines spanning all panels illustrate how phase errors from clock 1 are corrected by clock 2 and how the probability distribution in c is derived from the respective distribution shown in b. Vertical arrows in c indicate Dirac delta functions. Their integrals correspond to those of the respective shaded areas in b. As shown here, phase errors from clock 1 are corrected fully by clock 2 in nearly all cases. Additional noise introduced by clock 2 is treated separately (see main text).

Frequency instability

Based on these observations, we estimate the frequency instability of an actual compound clock that uses a single-ion clock as clock 2 and a lattice clock as clock 1. For simplicity, we assume that both clocks operate at the frequency of a strontium lattice clock. Furthermore, we assume a frequency noise spectrum of the interrogation laser and individual probing sequences of the clocks that are equivalent to our proof-of-principle experiment and a dead time Tdead = 0.25 s for preparation and read-out. The frequency instability resulting from the observed imperfections of the dynamical decoupling (σy,dd(τ) = 2 × 10−16(τ/s)−1/2) remains well below the contributions from QPN (σy,QPN(τ) = 6 × 10−16(τ/s)−1/2) and the Dick effect (σy,Dick(τ) = 5 × 10−16(τ/s)−1/2). The total frequency instability achieved by the compound clock is about σy(τ) = 8 × 10−16(τ/s)−1/2, for a laser with only 77 ms coherence time. The compound clock thus takes about a factor of 14 less averaging time to reach a given measurement precision than a comparable stand-alone single-ion clock (σy(τ) = 31 × 10−16(τ/s)−1/2) operating with an interrogation time close to that coherence limit (Ti = 71 ms) and the same dead time.

Similar improvements of clock performance are expected for clocks using state-of-the-art ultrastable lasers. The laser system reported in ref. 15 has a thermal noise floor of about \({\rm{mod}}\ {\sigma }_{y}=4\times 1{0}^{-17}\) in its modified Allan deviation, which results in a coherence time Tco ≈ 2.5 s for Ramsey interrogation at the strontium clock’s frequency. If we allow for similar phase errors due to imperfections of dynamical decoupling as expected in our experiment the interrogation time of a compound clock using this local oscillator can be extended to about one minute. Even if these errors were exceeded to a similar extent as observed experimentally, the resulting contribution to instability would remain well below that from QPN for the case considered here. A single-ion clock then reaches a QPN-limited instability of σy(τ) = 5 × 10−17(τ/s)−1/2 as part of a compound clock. Averaging times reduce by a factor of about 24 compared to stand-alone operation of the clock. Achieving similar performance of the stand-alone clock would require improving the frequency instability of the laser system by this same factor, i.e. to \({\rm{mod}}\ {\sigma }_{y}\;<\; 2 \times 1{0}^{-18}\).

Conclusion

The compound clock scheme presented here can thus expedite high-performance clock comparisons by more than an order of magnitude. Such progress is essential for the practicality of comparing future and even existing ion clocks. In the case of today’s best ion clocks1,27 measurements at 1 × 10−18 uncertainty would require less than an hour of averaging time in a compound clock rather than a few weeks as required at their present instability1,27. The problem has thus been in the focus of research for some time: Correlated interrogation of two clocks16,38 rejects laser phase fluctuations in direct comparisons. Moreover, the frequency difference between two clocks can be exploited to operate one or, in case of two lattice clocks, both beyond the laser coherence limit18. The compound clock scheme allows operating a clock beyond the laser coherence limit more generally. In particular, it improves the absolute frequency stability of the clock rather than only that of its frequency ratio to a specific, coherently linked clock. Similar to the scheme presented in ref. 18, it requires little additional hardware, since lattice clocks for coarse measurement are already available in most laboratories that operate high-performance optical clocks. While there are other techniques that allow tracing the laser phase beyond the coherence limit, e.g. weak measurements39,40,41, the dynamical decoupling protocol has been designed to do so using only standard experimental techniques.

Expediting high-performance comparisons of present and future clocks at uncertainties of 1 × 10−18 and below is important not only for the feasibility of evaluating and comparing these clocks but also for the many applications that aim to resolve time-dependent effects using optical clocks. Ion clocks are already used for such applications frequently, e.g. tests of Lorentz symmetry1 and the search for ultralight scalar dark matter10. Precision spectroscopy on highly charged ions is well suited for such applications30, as well, and may benefit similarly, as several highly charged ion species feature ultranarrow transitions with lifetimes of several days and longer. In each case, reducing the clock’s frequency instability results directly in an improved measurement sensitivity and may enable the investigation of phenomena that would remain inaccessible due to their required time resolution and measurement sensitivity otherwise. Therefore, implementing techniques that allow such improvements with existing technology, such as the compound clock scheme and the other techniques discussed above, is crucial for pushing both the development of optical clocks and their applications.

Methods

Interrogation laser setup

The interrogation laser of our strontium lattice clock at νSr ≈ 429 THz has been described in detail in ref. 14. Its frequency stability has since been improved further42 by stability transfer from one of the ultrastable lasers described in ref. 15 via a single branch of an optical frequency comb using the transfer oscillator scheme43,44,45. That laser is stabilised to a cryogenic monocrystalline silicon resonator near ν = 194.4 THz. Its modified Allan deviation has a flicker frequency noise floor of about \({\rm{mod}}\ {\sigma }_{y}=4\times 1{0}^{-17}\) and a similar contribution from white frequency noise at an averaging time τ = 1 s15.

Laser light from the interrogation laser is delivered to the atoms via an optical fibre. We have modified the optical path length stabilisation (PLS) such that it is compatible with multi-pulse interrogation (cf. ref. 46): If a single beam is used for both spectroscopy and PLS two subsequent pulses may differ in phase by Δφ = π because the phase-locked loop in the PLS is only sensitive to the round-trip phase. Our observations have shown that these phase slips occur occasionally. Therefore, we use two separate beams: a resonant probe beam for spectroscopy and an off-resonant (Δν = −2 MHz) pilot beam, which remains switched on throughout the entire spectroscopy sequence, for the PLS servo loop. Both beams are derived from the same acousto-optic modulator in front of the fibre so that they nearly co-propagate. The optical path length of the probe beam is then co-stabilised via the pilot beam.

Artificial frequency noise

We imprint additional frequency noise directly onto the probe beam, by changing its radio-frequency offset with respect to the pilot beam at the acousto-optic modulator of the PLS. A direct digital synthesiser (DDS) based on a field programmable gate array provides a radio-frequency signal with the appropriate frequency noise for this purpose.

A set of pre-generated samples of pseudo-random power-law frequency noise47 is uploaded to the DDS prior to the experiment. Here, we use artificial frequency noise spectra with \({S}_{y}(f)=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i = -1}^{0}{h}_{i}{f}^{i}\), where white frequency noise h0 = 1.8 × 10−31 Hz−1 (i.e. σy = 3 × 10−16 at τ = 1 s) and flicker frequency noise h−1 = 1.2 × 10−30 (σy = 1.3 × 10−15) with respect to the transition frequency of the clock (Fig. 3c). Each sample has a duration of about 1 s with a time resolution of about 60 μs.

During the experiment, the computer control system of the clock selects one of these samples and triggers the DDS at the beginning of the probe sequence. The DDS replays the selected noise sample from the beginning each time it is triggered. The clock’s pulse pattern generator is used to generate the trigger signal, for precise and reproducible timing with respect to the probe sequence.

Experimental setup

Our strontium optical lattice clock has been described in previous publications42,48,49. For the experiments reported here, laser frequency noise is dominated by the artificial contribution discussed in the previous section and shown in Fig. 3c. We adjust the power of the spectroscopy beam such that it results in a π-pulse duration Tπ = 1.0 ms, which keeps imperfections of the dynamical decoupling due to the Dick effect low. A suitable spectroscopy sequence for clock 1 with an interrogation time \({T}_{{\rm{i}}}^{\prime}\approx 495\ {\rm{ms}}\) is determined following the procedure discussed in the main text. We use a spectroscopy sequence with M = 16 flip pulses such that Td = 30 ms < Tco and choose ϵ = 0.12π such that the central fringe is broad enough to trace the expected phase deviations unambiguously.

For the experiments reported here, we operate the clock in a repeating cycle S1, S2, \({\tilde{S}}_{1}\), \({\tilde{S}}_{2}\), \({M}_{1}^{(i)}\), \({M}_{2}^{(i)}\), \({\tilde{M}}_{1}^{(i+1)}\), \({\tilde{M}}_{2}^{(i+1)}\), where S1 (S2) are stabilisation interrogations using the probe sequence of clock 1 (2) and the undisturbed clock laser and \({M}_{1}^{(i)}\) (\({M}_{2}^{(i)}\)) are measurement interrogations using the sequence of clock 1 (2) and artificial frequency noise from the i-th sample. The line shapes are inverted for every second pair of interrogations, as indicated by tildes, by reversing the phase shifts of the pulses. The stabilisation interrogations with the probe sequence of clock 2 are used to lock the laser frequency to the atomic transition frequency and compensate any residual frequency drift of the interrogation laser during the experiment. Those using the probe sequence of clock 1 are not used. Each pair of measurement interrogations is used to perform a phase measurement for one of the frequency noise samples. Here, the phase \({\phi }_{1}^{(i)}\) measured by clock 1 (\({M}_{1}^{(i)}\) or \({\tilde{M}}_{1}^{(i)}\)) is reconstructed from the observed excitation probability, using a look-up table for the specific probe sequence and correcting for the observed contrast. The subsequent measurement interrogation (\({M}_{2}^{(i)}\) or \({\tilde{M}}_{2}^{(i)}\)), which uses the same noise sample but the probe sequence of clock 2, receives this measurement result and uses it to adjust the phase of its second excitation pulse, as shown in Fig. 1. The observed excitation probability is once again corrected for the observed contrast and then converted to the observed phase \({\phi }_{2}^{(i)}\). Here, we approximate the Ramsey line shape by a sine function and assume that the result falls within the invertible range.

As there is no feedback to the clock, these results are analysed in post-processing for simplicity: The imprinted phase deviations \({\phi }_{0}^{(i)}\) are computed by numerically integrating the frequency noise of respective samples over the interrogation time and compared to the phase measurement results \({\phi }_{1}^{(i)}\) of clock 1 and \({\phi }_{{\rm{tot}}}^{(i)}={\phi }_{1}^{(i)}+{\phi }_{2}^{(i)}\) of the compound clock. Figure 4 shows the difference between the measured and expected values.

Probe light shift

We observe a differential shift on the order of a hertz between the line centres of the two probe sequences. We cancel it by applying an offset to the clock laser frequency in all interrogations using the probe sequence of clock 1. The occurrence of such a shift is not unexpected since the probe sequence of clock 1 with its many flip pulses is more sensitive to probe light shifts than the two-pulse sequence used by clock 2. However, it does not impede operation of a compound clock or its systematic uncertainty, which is governed by clock 2.

Phase errors due to near-synchronous interrogation

Reading out the atomic state of clock 1 and forwarding the phase estimate to clock 2 (Fig. 1) introduces a brief window during which only one of the clocks monitors the laser. Laser phase noise that occurs during this time directly affects the determination of the correct Ramsey fringe in clock 2. Hence, the delay \({T}_{{\rm{i}}}-{{T}_{{\rm{i}}}}^{\prime}\) must be kept short. For the sake of simplicity, we use the same interrogation time in both clocks (\({T}_{{\rm{i}}}={T}_{{\rm{i}}}^{\prime}\)) for the experiments presented here, which use sequential interrogation of a single clock (see main text). In practice, the delay can easily be kept well below the coherence time of typical interrogation lasers.

Phase errors due to dynamical decoupling imperfections

Phase measurement errors in clock 1 caused by imperfections of the dynamical decoupling can be calculated analogously to the Dick effect22, by analysis of the clock’s sensitivity to laser frequency fluctuations.

The frequency sensitivity g(t) of a spectroscopy protocol determines the change in excitation probability δpe caused by a time-dependent frequency error δν(t) of the probe laser, which is given by22,23,50

for interrogation time Ti in the linear response regime. If the sensitivity function of clock 1 had the same shape as that of clock 2, which is nearly rectangular, there would be no imperfections of the dynamical decoupling. In practice, this will never be the case due to the different pulse sequences used in the two clocks (Fig. 1). The frequency sensitivity g(t) of clock 1 can be split into a signal component \(\bar{g}={T}_{{\rm{i}}}^{-1}\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{0}^{{T}_{{\rm{i}}}}g(t){\rm{d}}t\) and a noise component \({g}_{{\rm{n}}}(t)=g(t)-\bar{g}\) such that

where ϕ is the laser phase deviation accumulated during the interrogation time. Laser frequency noise with single-sided power spectral density Sy(f) thus gives rise to noise of the measured excitation probability with variance51

where \({\hat{g}}_{{\rm{n}}}(f)\) is the complex Fourier transform of gn(t). This corresponds to a phase measurement error with variance

The frequency sensitivity of the protocol presented here is shown in Fig. 3a for the parameters used in the proof-of-principle experiment. The noise component gn(t) stems mainly from the greatly increased frequency sensitivity during flip pulses. Therefore, the phase measurement is particularly sensitive to laser frequency noise at Fourier frequencies that are harmonics of \(f\approx {({T}_{\pi }+{T}_{{\rm{d}}})}^{-1}\). The relevant Fourier coefficients of the sensitivity function decrease with shortening Tπ and roll off above a corner frequency \({f}_{{\rm{c}}}\approx {T}_{\pi }^{-1}\), which restricts useful π-pulse durations.

Phase errors due to these imperfections of the decoupling depend on the noise type (Sy ∝ fα) that dominates at the relevant Fourier frequencies. For flicker or white frequency noise (α = 0 or −1), they decrease towards shorter pulse duration Tπ, whereas they increase for flicker or white phase noise (α = 1 or 2). White frequency noise is the dominant noise process for our laser system15 at Tπ ≈ 1 ms. The spectroscopy sequence used here gives rise to RMS phase measurement errors σϕ,0 = 0.12 π from artificial laser noise and σϕ,i = 0.014 π from frequency noise of the undisturbed laser.

In contrast with the procedure for estimating the frequency instability due to the Dick effect22 in atomic clocks, the dead time and total cycle time are not relevant for calculating the effect of the dynamical decoupling imperfections. This is because the atomic excitation is being used in the dynamical decoupling scheme to estimate the phase accumulated by the laser only during the interrogation pulse, not the phase accumulated during the entire clock cycle.

Phase errors due to QPN

Like the dynamical decoupling imperfections, QPN causes phase measurement noise in clock 1 that may lead to incorrect determination of the Ramsey fringe.

The measured excitation probability has a variance \({\sigma }_{{p}_{e}}^{2}={\bar{p}}_{e}(1-{\bar{p}}_{e}){N}^{-1}\) due to QPN for N uncorrelated atoms, where \({\bar{p}}_{e}\) is the expectation value. The variance of the resulting phase measurement noise is then given by Eq. (5). We interrogate about 700 atoms per measurement for the experiments reported here. This corresponds to contributions \({\sigma }_{{p}_{e}}=0.02\) and \({\sigma }_{{\phi }_{1}}=0.06\pi\).

Effect of phase errors by clock 1 on the compound clock

The compound clock compensates errors of clock 1 using the complementary narrow-fringe, high-resolution measurement by clock 2. This scheme works well as long as the phase errors Δϕ1 from clock 1 stay within ±π/2. If the phase error exceeds this threshold clock 2 is assigned an incorrect fringe, which causes a non-zero residual phase error Δϕtot of the compound clock. Note that, in contrast to a stand-alone system, such events do not cause the clock to lock onto an incorrect fringe because it will be detected by clock 1 and corrected in the next measurement. Nevertheless, they give rise to additional noise in the compound clock and increase its frequency instability. The probability density function of the compound clock’s residual errors results from mapping the probability density function of phase errors by clock 1 onto the corresponding phase errors of the compound clock, as shown in Fig. 5. This can be treated as independent of additional noise introduced by clock 2 in good approximation. Finally, the contribution of the residual phase errors to the clock’s frequency instability results from the RMS phase error, which is estimated from the probability density function.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Sanner, C. et al. Optical clock comparison test of Lorentz symmetry. Nature 567, 204–208 (2019).

Delva, P. et al. Test of special relativity using a fiber network of optical clocks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 221102 (2017).

Rosenband, T. et al. Frequency ratio of Al+ and Hg+ single-ion optical clocks; metrology at the 17th decimal place. Science 319, 1808–1812 (2008).

Huntemann, N. et al. Improved limit on a temporal variation of mp/me from comparisons of Yb+ and Cs atomic clocks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 210802 (2014).

Godun, R. M. et al. Frequency ratio of two optical clock transitions in 171Yb+ and constraints on the time-variation of fundamental constants. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 210801 (2014).

Derevianko, A. & Pospelov, M. Hunting for topological dark matter with atomic clocks. Nat. Phys. 10, 933–936 (2014).

Wcisło, P. et al. Searching for topological defect dark matter with optical atomic clocks. Nat. Astron. 1, 0009 (2016).

Stadnik, Y. V. & Flambaum, V. V. Enhanced effects of variation of the fundamental constants in laser interferometers and application to dark-matter detection. Phys. Rev. A 93, 063630 (2016).

Wcisło, P. et al. New bounds on dark matter coupling from a global network of optical atomic clocks. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau4869 (2018).

Roberts, B. M. et al. Search for transient variations of the fine structure constant and dark matter using fiber-linked optical atomic clocks. N. J. Phys. 22, 093010 (2020).

Grotti, J. et al. Geodesy and metrology with a transportable optical clock. Nat. Phys. 14, 437–441 (2018).

Takamoto, M. et al. Test of general relativity by a pair of transportable optical lattice clocks. Nat. Photonics 14, 411–415 (2020).

Kolkowitz, S. et al. Gravitational wave detection with optical lattice atomic clocks. Phys. Rev. D. 94, 124043 (2016).

Häfner, S. et al. 8 × 10−17 fractional laser frequency instability with a long room-temperature cavity. Opt. Lett. 40, 2112–2115 (2015).

Matei, D. G. et al. 1.5μm lasers with sub-10 mHz linewidth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 263202 (2017).

Chou, C. W., Hume, D. B., Thorpe, M. J., Wineland, D. J. & Rosenband, T. Quantum coherence between two atoms beyond Q = 1015. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 160801 (2011).

Takamoto, M., Takano, T. & Katori, H. Frequency comparison of optical lattice clocks beyond the Dick limit. Nat. Photonics 5, 288–292 (2011).

Hume, D. B. & Leibrandt, D. R. Probing beyond the laser coherence time in optical clock comparisons. Phys. Rev. A 93, 032138 (2016).

Schioppo, M. et al. Ultra-stable optical clock with two cold-atom ensembles. Nat. Photonics 11, 48–52 (2017).

Oelker, E. et al. Demonstration of 4.8 × 10−17 stability at 1 s for two independent optical clocks. Nat. Photonics 13, 714–719 (2019).

Itano, W. M. et al. Quantum projection noise: Population fluctuations in two-level systems. Phys. Rev. A 47, 3554–3570 (1993).

Dick, G. J. Proc. 19th Annu. Precise Time and Time Interval Meeting, Redendo Beach, 1987 133–147. http://tycho.usno.navy.mil/ptti/1987papers/Vol%2019_13.pdf (U.S. Naval Observatory, Washington, DC, 1988).

Quessada, A. et al. The Dick effect for an optical frequency standard. J. Opt. B Quantum Semiclass. Opt. 5, S150–S154 (2003).

Riehle, F. Frequency Standards: Basics and Applications (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2004).

Wineland, D. J., Bollinger, J. J., Itano, W. M., Moore, F. L. & Heinzen, D. J. Spin squeezing and reduced quantum noise in spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. A 46, R6797–R6800 (1992).

Pedrozo-Peñfiel, E. et al. Entanglement-enhanced optical atomic clock. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.07501 (2020).

Brewer, S. M. et al. 27Al+ quantum-logic clock with a systematic uncertainty below 10−18. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 033201 (2019).

McGrew, W. F. et al. Atomic clock performance beyond the geodetic limit. Nature 564, 87–90 (2018).

Bothwell, T. et al. JILA SrI optical lattice clock with uncertainty of 2.0 × 10−18. Metrologia 56, 065004 (2019).

Kozlov, M. G., Safronova, M. S., Crespo López-Urrutia, J. R. & Schmidt, P. O. Highly charged ions: Optical clocks and applications in fundamental physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 045005 (2018).

Bekker, H. et al. Detection of the 5p – 4f orbital crossing and its optical clock transition in Pr9+. Nat. Commun. 10, 5651 (2019).

Rosenband, T. et al. Observation of the 1S0 - 3P0 clock transition in 27Al+. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 220801 (2007).

Muniz, J. A., Young, D. J., Cline, J. R. K. & Thompson, J. K. Cavity-QED determination of the natural linewidth of the 87Sr millihertz clock transition with 30 μHz resolution. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2007.07855.pdf (2020).

Roberts, M. et al. Observation of an electric octupole transition in a single ion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1876–1879 (1997).

Viola, L., Knill, E. & Lloyd, S. Dynamical decoupling of open quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 2417–2421 (1999).

Hahn, E. L. Spin echos. Phys. Rev. 80, 580–594 (1950).

Grebing, C. et al. Realization of a timescale with an accurate optical lattice clock. Optica 3, 563–569 (2016).

Clements, E. R. et al. Lifetime-limited interrogation of two independent 27Al+ clocks using correlation spectroscopy. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2007.02193.pdf (2020).

Vanderbruggen, T. et al. Feedback control of coherent spin states using weak nondestructive measurements. Phys. Rev. A 89, 063619 (2014).

Shiga, N. & Takeuchi, M. Locking local oscillator phase to the atomic phase via weak measurement. N. J. Phys. 14, 023034 (2011).

Shiga, N., Mizuno, M., Kido, K., Phoonthong, P. & Okada, K. Accelerating the averaging rate of atomic ensemble clock stability using atomic phase lock. N. J. Phys. 16, 073029 (2014).

Schwarz, R. et al. Long term measurement of the 87Sr clock frequency at the limit of primary Cs clocks. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033242 (2020).

Hagemann, C. et al. Providing 10−16 short-term stability of a 1.5μm laser to optical clocks. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 62, 1556–1562 (2013).

Benkler, E. et al. End-to-end topology for fiber comb based optical frequency transfer at the 10−21 level. Opt. Express 27, 36886–36902 (2019).

Benkler, E. et al. End-to-end topology for fiber comb based optical frequency transfer at the 10−21 level: erratum. Opt. Express 28, 15023–15024 (2020).

Falke, S., Misera, M., Sterr, U. & Lisdat, C. Delivering pulsed and phase stable light to atoms of an optical clock. Appl. Phys. B 107, 301–311 (2012).

Kasdin, N. J. Discrete simulation of colored noise and stochastic processes and 1/fα power law noise generation. Proc. IEEE 83, 802–827 (1995).

Al-Masoudi, A., Dörscher, S., Häfner, S., Sterr, U. & Lisdat, C. Noise and instability of an optical lattice clock. Phys. Rev. A 92, 063814 (2015).

Falke, S. et al. The 87Sr optical frequency standard at PTB. Metrologia 48, 399–407 (2011).

Dick, G. J., Prestage, J., Greenhall, C. & Maleki, L. Proc. 22nd Annual Precise Time and Time Interval (PTTI) Applications and Planning Meeting, Vienna VA, USA 487–509. http://tycho.usno.navy.mil/ptti/1990/Vol%2022_42.pdf (1990).

Hobson, R. An optical lattice clock with neutral strontium. PhD thesis, https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:d52faaaf-307c-4b48-847f-be590f46136f (2016).

Johansson, J. R., Nation, P. D. & Noria, F. QuTiP 2: A Python framework for the dynamics of open quantum systems. Comput. Phys. Comm. 184, 1234 – 1240 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Häfner, Th. Legero, and E. Benkler for operating the ultrastable laser system and optical frequency comb that are used for stabilisation of our interrogation laser system. We thank M. Misera for developing the frequency noise generator. This work has received funding from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) within CRC 1227 (‘DQ-mat’, project B02) and under Germany’s Excellence Strategy—EXC-2123 QuantumFrontiers—390837967. This work was partially supported by the Max Planck–RIKEN–PTB Center for Time, Constants and Fundamental Symmetries. R.H. has been supported by the European Union’s Horizon H2020 MSCA RISE programme under Grant Agreement Number 691156 (Q-SENSE). M.B. has been supported by a research fellowship within the project ‘Enhancing Educational Potential of Nicolaus Copernicus University in the Disciplines of Mathematical and Natural Sciences’ (Project No. POKL.04.01.01-00-081/10). U.S. acknowledges funding from the project EMPIR 17FUN03 USOQS. EMPIR projects are co-funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and the EMPIR Participating States.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D., M.B., R.H., U.S. and C.L. developed the protocol and devised the proof-of-principle experiment; S.D., A.A.-M., M.B., R.S., R.H. and C.L. fitted the strontium clock for the experiment; S.D., A.A.-M. and R.S. acquired and analysed the data. All authors were involved in discussions and preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dörscher, S., Al-Masoudi, A., Bober, M. et al. Dynamical decoupling of laser phase noise in compound atomic clocks. Commun Phys 3, 185 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00452-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00452-9

This article is cited by

-

Quantum lock-in measurement of weak alternating signals

Quantum Frontiers (2024)

-

Improved interspecies optical clock comparisons through differential spectroscopy

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Information theoretical limits for quantum optimal control solutions: error scaling of noisy control channels

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Comparing ultrastable lasers at 7 × 10−17 fractional frequency instability through a 2220 km optical fibre network

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.