Abstract

The Josephson effect in scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) is an excellent tool to probe the properties of a superconductor on a local scale. We use atomic manipulation in a low temperature STM to create mesoscopic single channel contacts and study the Josephson effect at arbitrary transmissions. We observe significant deviations from the Ambegaokar-Baratoff formula relating the critical current to the order parameter starting from transmissions of τ > 0.1. Using the full current-phase relation, we model the Josephson effect in the dynamical Coulomb blockade regime, where the charging energy of the junction capacitance cannot be neglected, and find excellent agreement with the experimental data. Projecting the current-phase relation onto the charge transfer operator shows that at high transmission, non-linear behaviour arises and multiple Cooper pair tunneling may occur. Our model includes these deviations, which become non-negligible in Josephson-STM, for example, when scanning across single adatoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Superconductivity is an example of a macroscopic quantum phenomenon, which continues to fascinate physicists and trigger technological developments well over a century after its original discovery. Impurities and defects, however, are known to induce sub-gap excitations, which lead to local changes in the superconductor’s ground state. Yu–Shiba–Rusniov states, Majorana-bound states, Kondo resonances and pair density waves are all predicted to lead to local changes in the superconducting condensate1,2,3,4,5. Quantifying these modifications promises to improve the current understanding of superconductivity in mesoscopic systems and to open new avenues in material design for emerging applications, especially in quantum computing. Detecting such local changes in the order parameter has since become a major goal of research in superconductivity3,4,6,7,8,9,10,11.

Information about the Cooper pair (CP) condensate is encoded, for example, in the Josephson current flowing between two weakly coupled superconducting electrodes12,13. Using superconducting tips in a scanning tunnelling microscope (STM), it is possible to map local variations in the Josephson current in the vicinity of defects in a superconducting sample and extract local values of the critical current IC. Josephson STM (JSTM) data are generally analysed on the basis of the Ambegaokar–Baratoff (AB) formula3,6,8,10,14,15,16:

which establishes the product of the Josephson critical current IC and normal state resistance RN as a fundamental quantity directly proportional to the order parameter Δ (T is the temperature and kB is Boltzmann’s constant). As the temperature dependence is rather weak for kBT ≪ Δ, we will assume the low-temperature limit (see Supplementary Note 1). While RN is directly measurable in the experiment, IC needs to be extracted through a theoretical model and requires detailed knowledge of the electromagnetic environment of the junction17,18,19,20.

However, the derivation of the AB formula predates the invention of the STM by two decades. Equation (1) sets out to describe planar tunnel junctions with a macroscopic surface area where the current is carried by many nearly opaque transmission channels. The experimental reality in the STM is starkly different from this: operating at sub-nanometre spatial resolution, the STM junction is a mesoscopic point contact with the tunnel current carried by only a few channels at arbitrary transmission (AT)21,22. Furthermore, at very low temperatures (T ≪ 1 K), the STM typically operates in the dynamical Coulomb blockade (DCB) regime, where the phase is no longer a classical well-defined variable15,17,19,20,23,24,25. Also, in this regime thermal-phase fluctuations are reduced such that the previously used Ivanchenko–Zil’berman model is not applicable6,8. Therefore, a more generalized description is needed to accommodate the few channel, high transmission contacts in STM to explore Josephson physics beyond the AB approximation.

Here, we report the controlled preparation of single-channel Josephson atomic point contacts to examine deviations from the AB model as a function of channel transmission. We prepare Josephson point contacts18,26,27,28,29,30 in our STM using atomic manipulation and extract the number of transmission channels and their respective transmission, that is, the mesoscopic PIN code (in the mesosocopic community the number of transport channels and their transmission is referred to as PIN code in analogy to the “Personal Identification Number” used in financial transactions), using a fitting model29,31. Through single atom manipulation and careful tip preparation, we construct junctions with a single dominant transmission channel across a wide range of conductances. These point contacts form a highly controllable model system in which we can explore Josephson physics beyond the low transmission regime. Indeed, we observe a breakdown of the AB formula beginning at modest conductances. We show that the product ICRN is then no longer uniquely determined by Δ, but is also influenced by the mesoscopic PIN code and the non-linearity of the current-phase relation as a function of the channel transmission. We develop a new DCB junction model valid in the single-channel limit, which accurately describes our data and could form the basis for a more general few channel model to be used in JSTM data analysis. This DCB junction model considers the Josephson junction in the presence of phase fluctuations by transforming the energy-phase relations from phase space to charge space.

Results

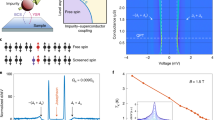

Characterizing the atomic contact

We first characterize the tip by acquiring a low-conductance tunnel spectrum above the clean Al(100) surface to extract the tip gap Δtip, which is required for the following analysis (for experimental details see “Methods” and Supplementary Note 2). Typical data and a fit using a Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer model for both tip and sample are shown in Fig. 1d. We then measure a series of current–voltage I(V) curves above the aluminium adatom. The tip–sample distance is decreased between consecutive measurements to increase the conductance. The superconducting gap is gradually filled with sub-gap states as multiple Andreev reflections (MARs) start contributing to the total current32,33. We exploit the MAR signature for mesoscopic PIN code analysis according to the methods published in refs. 29,31,34,35 (see Supplementary Note 3 for a detailed description). Our fitting model includes three independent transport channels, their respective transmissions being free parameters in the fit21,22. Additional channels do not improve the quality of the fit. The tip is then treated by controlled indentation into the pristine Al(100) surface until the PIN code analysis shows a single dominant transport channel across all channel transmissions. We now focus our analysis on the transport properties of such a single-channel junction.

a Topographic image of the Al(100) surface with a surface defect as a reference (white protrusion with black halo) before atomic manipulation. b An Al atom has been pulled from the surface (black depression on the lower left) and placed on to the surface again (white protrusion on the upper right). The scan area in a, b is 5 nm × 5 nm. The contrast has been adjusted to display the details of the lattice corrugation, such that the adatom appears completely white. c Schematic of the tunnel junction. The tip of the scanning tunnelling microscope is placed directly above an Al adatom creating a mesoscopic point contact. d Fit of a quasiparticle empty gap differential conductance spectrum at a conductance setpoint of 36 nS.

A typical set of I(V) curves for a single-channel junction is shown in Fig. 2a. All I(V) curves are acquired with the same tip at varying tip–sample distances, given relative to the point where the normal state conductance GN reaches G0. The feedback loop is disengaged at a voltage of 1 mV, far outside the gap. In the lowest conductance I(V) curve, shown in dark blue, the gap edge is visible as a prominent step at Δtip + Δsample = 360 μV. Below the gap edge, the MARs are visible as a series of steps. As the normal state conductance at 1 mV increases, higher and higher orders of MARs contribute to the current, and the sub-gap features are progressively washed out. Superimposed on the experimental data are the fit results from the PIN code analysis. We find excellent agreement with the experimental data, except for small deviations in the low-conductance curves, which are likely due to inelastic processes arising from tunnelling in the DCB regime, which are not included in our model. Note that the MAR model does not include the Josephson effect. This leads to deviations from the full I(V) characteristic below ca. 70 μV (blue shaded area in Fig. 2a). Figure 2b shows the result of the PIN code analysis for each of the curves in Fig. 2a. We found that the junction is dominated by a single transport channel, which eclipses all other contributions by at least an order of magnitude across all tip–sample distances. We can thus realize a controllable and stable single-channel Josephson point contact in our STM. For comparison, we have measured several different sites on the bare Al(100) surface as well as on an impurity (I), which is shown in Fig. 2c. The corresponding distribution of channel transmissions for each site is shown in Fig. 2d along with the Al adatom. We found that each location has a slightly different mesoscopic PIN code and conclude that the Al adatom has the most pronounced single-channel character (for details see the Supplementary Note 4). With the transport parameters fixed for the corresponding data sets, we can now turn to the low-voltage regime to analyse the effect of single-channel transport on the Josephson current and evaluate the validity of the AB approach.

a Andreev reflection data (thick lines) and fits (thin lines) for different tip–sample distances (the origin of the length scale is at GN = G0) used for PIN code analysis. For symmetry reasons and based on the valence of Al, we have assumed three channels. The blue shaded area is the energy range for the analysis of the Josephson spectra in Fig. 3. b The three channels and their transmission for the different spectra in a as a function of tip–sample distance. The second and the third channels have equal transmission. c Topographic image (3 nm × 3 nm) of Al(100) near an impurity (foreign atom). Different sites are marked on and off the impurity (I), where the mesoscopic PIN code was extracted. d The channel transmissions are plotted for the different sites in c along with the sum (Σ). For some sites the second and third channel have the same transmission. For comparison, the channel transmission through the Al adatom is plotted showing the most pronounced single-channel behaviour. The spectra were taken at a normal state conductance of 0.17G0.

Single-channel Josephson effect

Due to the low base temperature of the instrument, the charging energy of the junction becomes the dominant energy scale in our experiment. We are thus operating in the DCB regime where interactions with the electromagnetic environment can no longer be neglected. The Josephson current arises from inelastic tunnelling of CPs, with the broadening determined by the P(E) function, which models energy exchange with the surroundings. The I(V) relation for the Josephson current in the DCB regime is17

where \({E}_{{\rm{J}}}=\frac{\hslash {I}_{{\rm{C}}}}{2e}\) is the Josephson energy, which we calculate from the AB formula (cf. Eq. (1) or (3) below, and V the junction bias). The factor 2 in the argument of the P(E) function reflects the charge of the CPs. The critical current can be extracted from the I(V) characteristic with knowledge of the P(E) function. The AB formalism relates EJ and Δ through

This approach describes a junction with an arbitrary number of transport channels, as long as the transmissions of all individual channels remains low (τi ≪ 1).

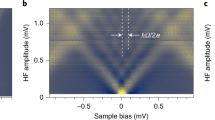

Figure 3 shows I(V) curves of a typical STM single-channel Josephson contact at various transmissions with a focus on the low-voltage regime and the Josephson effect. At low transmission (Fig. 3a), the Josephson effect, visible as a dip-and-peak feature centred at zero bias, dominates the spectrum. This feature is gradually washed out as we move towards higher transmission and MARs begin to become more relevant in the low-voltage regime. We model the experimental data using the P(E) model from Eq. (2) and an estimate for EJ from Eq. (3) (see Supplementary Note 5). The results are shown as yellow lines in Fig. 3 and labelled as AB in the legend. Even at modest transmissions of τ = 0.09, the AB description underestimates the Josephson peak height. The discrepancy between the prediction of the AB model and the experimental data increases with increasing transmission (see Fig. 3a–g). We find that the AB theory indeed fails to describe the Josephson junction at high transmission. This regime is not well explored in experiments nor described by theory at present.

a–g Josephson spectra at different transmissions (the total transmission τ is indicated in each panel). A clear deviation between the Ambegaokar–Baratoff approach (AB) and the full Andreev-bound state relation at arbitrary transmission (AT) can be seen at higher transmission. For the transmissions in f, g, non-adiabatic processes become significant at higher bias voltages, such that our model is only applicable within the blue shaded areas. h shows the χ2 values of the fits. The arbitrary transmission model yields low χ2 values throughout (indicating good agreement), except in the red shaded region, where non-adiabatic processes become significant.

We propose an extension of the P(E) theory, which is valid in the single-channel limit and could serve as a basis for a more general few channel theory. The discrepancies between the experimental data and the AB theory can be traced to the non-sinusoidal energy-phase relation expected in high transmission contacts. The presence of higher-order terms in the Fourier transform of the energy-phase relation suggests the existence of tunnel processes transferring multiple CPs. To see this, we begin with the energy-phase relation for Andreev-bound states in a single channel at AT36

Equation (4) is illustrated in Fig. 4 for various values of τ. Next, we expand Eq. (4) into a Fourier series

and, in the spirit of P(E) theory, replace the phase φ by an operator to introduce the charge transfer operator eimφ, which is more appropriate to describe charge tunnelling in the DCB regime. The amplitudes Em as non-linear functions of τ are specified in Supplementary Note 6. Charge transfer is now described within a perturbative treatment applied to the operators eimφ, which represent the transfer of m CPs across the junction. We introduce new Pm(E) functions describing the probability of inelastic tunnel processes, where energy packages 2meV are exchanged with the environment during an m CP process (see Supplementary Note 7 for details):

and find a Josephson current for the single-channel case,

Note that in the low transmission limit the first-order coefficient in the Fourier series dominates and Eq. (7) reduces to Eq. (2) with \({E}_{1}=\frac{{E}_{{\rm{J}}}}{2}\). Past this limit, Eq. (3) breaks down and knowledge of the mesoscopic PIN code is required for an accurate description of the Josephson current.

a Andreev-bound state relation for high transmissions. As the gap closes, the probability for transitions between branches (non-adiabatic processes) becomes more likely. b Absolute value of the coupling coefficients ∣Em∣ at different transmissions in comparison to the coupling coefficient of the linear Ambegaokar–Baratoff model (EJ/2).

The results of the extended DCB theory (red lines in Fig. 3) from Eq. (7) are compared to the experimental data and the conventional DCB theory from Eq. (2). In Fig. 3h, the χ2 values for the calculated curves are plotted as function of total transmission. The lower χ2 values for the AT model indicate a much better agreement compared to the AB model (details of the χ2 calculation can be found in the Supplementary Note 8). Note that neither calculation involves any adjustable parameters, but uses the independently determined mesoscopic PIN code from the MAR analysis, gap parameters for tip and sample obtained from the quasiparticle spectrum at low conductance, and tunnel junction parameters entering the Pm(E) function(s) determined by the Josephson spectrum at lowest transmission (see Supplementary Notes 3 and 5). Without introducing additional parameters or assumptions, the AT model based on Eq. (7) gives a far better description of the experimental data than the conventional AB model (see fits in Fig. 3).

We find excellent agreement between the extended model and the experimental data over the whole voltage range of the Josephson peak up to a transmission of τ ≈ 0.8. Discrepancies past τ ≈ 0.8 are presumably due to non-adiabatic processes (transitions between the Andreev branches, cf. Eq. (4), Fig. 4a and Supplementary Note 9) in the total tunnel current. We estimate the adiabatic approximation on which Eqs. (4) and (7) are based to be valid below a threshold voltage of eVT = (1 − τ)Δ (shaded area in Fig. 3, see Supplementary Note 10). The contribution from non-adiabatic processes is to be expected as branch crossing (Landau–Zener transitions) between the Andreev-bound states above and below the Fermi level becomes increasingly important at high τ (see Fig. 4a).

The improved agreement in Fig. 3 is the result of the energy dependence of the Fourier amplitudes Em on the channel transmission τ. The Em take on a similar role as EJ in the AB model, but, in contrast to Eq. (3), have a non-linear dependence on the transmission τ. We compare the first three Fourier coefficients with EJ/2 calculated from Eq. (3) in Fig. 4(b). It is the non-linear increase of E1 (single CP transfer), which gives the dominant contribution to the deviations from the AB model37. At higher transmission, coefficients of higher order (E2, E3, ...) become increasingly important, implying that the transfer of packages of multiple CPs is relevant for the net charge current through the contact. Our theory thus predicts a small part of the Josephson current to be carried by the coherent tunnelling of several CPs in high transmission contacts.

Locally resolved Josephson effect

The consequences of the non-linear dependence can be directly seen in the locally resolved ICRN product near a nonmagnetic impurity on Al(100). The gap parameter Δ is independent of the presence of nonmagnetic impurities, such that the ICRN product is expected to be constant within the AB model (see Supplementary Note 11). The normal state conductance GN and the maximum Josephson current Is measured at constant height are shown in Fig. 5a and b, respectively. In the DCB regime, a relative local change in the critical current IC can be directly extracted from the relation \({I}_{{\rm{C}}}\propto \sqrt{{I}_{{\rm{s}}}}\) (cf. Eqs. (2) and (7)). Figure 5c shows the ICRN product normalized to the average value across the image. We find variations of up to 6%. Arguing within the AB model, this behaviour is in contradiction with the expected constant gap parameter. However, the AB model does not take into account any non-linearities in the conductance dependence. To understand this behaviour, we calculate the ICRN product using the AT model with a constant gap parameter Δ (for details see Supplementary Note 11), which is shown in Fig. 5d normalized to the average value across the image. We find a very similar relative change for both experimental and calculated data. This corroborates the non-linear dependence of the critical current on the channel transmission coefficients. We conclude that the ICRN product in general is not simply a function of the order parameter. Such non-linear changes have to be taken into account in JSTM data. Their severity has to be judged on a case-by-case basis.

a Map of the normal state conductance GN (\({R}_{{\rm{N}}}={G}_{{\rm{N}}}^{-1}\)) around an impurity on Al(100) measured at constant height. b Map of the current maximum Is of the Josephson peak at a bias voltage of V = 14 μV under the same conditions as in a. c Map of the ICRN product. The critical current IC is extracted from b through \({I}_{{\rm{C}}}\propto \sqrt{{I}_{{\rm{s}}}}\). The data are normalized to the average value. d Map of the ICRN product calculated from the arbitrary transmission model (Eqs. (4)–(7)). The variations in the ICRN product are due to the non-linear dependence of IC on RN. The gap parameter Δ is expected to be constant. All maps have a size of 2.2 nm × 2.2 nm.

Discussion

We have fabricated stable and highly controllable single-channel Josephson junctions in a low-temperature STM and use such contacts as model systems to study the Josephson effect at AT. The AB formula fails to accurately describe these measurements. Significant discrepancies are observed starting from transmission τ ≈ 0.1. We propose an alternative model in which we project the full Andreev-bound state relation for a single transport channel onto charge transfer operators for single and multiple CP tunnelling. The new model accurately describes the experimental data as function of transmission as well as on a local scale. The prediction of multiple CP tunnelling in high transmission single-channel Josephson contacts is an experimentally observable hallmark of our theory which could, for instance, be validated by coupling a Josephson junction to an external microwave source38.

The Josephson effect in the STM is becoming an important experimental tool used to quantify local changes in the superconducting condensate. Our findings show that the details of the junction geometry need to be considered in the data analysis as the local mesoscopic PIN code influences all quantities derived from the Josephson current. As the STM operates in the limit of few channels with AT, the non-linear dependence of the critical current on the channel transmission has to be considered. In general, the ICRN product is not simply proportional to the order parameter Δ. This is particularly true for magnetic adatoms and molecules, which are expected to lead to a local reduction of the order parameter and in whose vicinity changes in the number and transmission of transport channels are expected.

Methods

Experiments were performed in a low-temperature, ultra-high vacuum STM at 15 mK base temperature39. The Al(100) sample (TC = 1.2 K) was cleaned by repeated sputtering and annealing cycles. A polycrystalline aluminium wire was used as a tip. Due to the small capacitance of the STM junction, the charging energy is dominant at mK temperatures15 and the instrument operates in the DCB regime23,24,25 where energy exchange with the environment described by the P(E) function is no longer negligible17,19,20. Individual aluminium atoms were extracted from the surface with the STM tip resulting in a vacancy and an adatom (see Fig. 1a, b). When the tip is positioned above the adatom, a Josephson point contact is formed as schematically shown in Fig. 1c. For more details, see Supplementary Note 2.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Salkola, M. I., Balatsky, A. V. & Schrieffer, J. R. Spectral properties of quasiparticle excitations induced by magnetic moments in superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 55, 12648 (1997).

Flatté, M. E. & Byers, J. M. Local electronic structure of a single magnetic impurity in a superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 3761 (1997).

Randeria, M. T., Feldman, B. E., Drozdov, I. K. & Yazdani, A. Scanning Josephson spectroscopy on the atomic scale. Phys. Rev. B 93, 161115 (2016).

Graham, M. & Morr, D. K. Imaging the spatial form of a superconducting order parameter via Josephson scanning tunneling spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B96, 184501 (2017).

Lauke, L., Scheurer, M. S., Poenicke, A. & Schmalian, J. Friedel oscillations and Majorana zero modes in inhomogeneous superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 98, 134502 (2018).

Naaman, O., Teizer, W. & Dynes, R. C. Fluctuation dominated Josephson tunneling with a scanning tunneling microscope. Phy. Rev. Lett. 87, 097004 (2001).

Rodrigo, J. G., Suderow, H. & Vieira, S. On the use of STM superconducting tips at very low temperatures. Eur. Phys. J. B 40, 483 (2004).

Kimura, H., BarberJr, R. P., Ono, S., Ando, Y. & Dynes, R. C. Josephson scanning tunneling microscopy: a local and direct probe of the superconducting order parameter. Phys. Rev. B 80, 144506 (2009).

Šmakov, J., Martin, I. & Balatsky, A. V. Josephson scanning tunneling microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 64, 212506 (2001).

Rodrigo, J. G., Crespo, V. & Vieira, S. Josephson current at atomic scale: tunneling and nanocontacts using a STM. Phys. C 437, 270 (2006).

Hamidian, M. H. et al. Detection of a Cooper-pair density wave in Bi2 Sr2 CaCu2 O8 + x. Nature 532, 343 (2016).

Josephson, B. D. Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling. Phys. Lett. 1, 251 (1962).

Martín-Rodero, A., García-Vidal, F. J. & LevyYeyati, A. Microscopic theory of Josephson mesoscopic constrictions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 554 (1994).

Ambegaokar, V. & Baratoff, A. Tunneling between superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 10, 486 (1963).

Jäck, B. et al. Critical Josephson current in the dynamical Coulomb blockade regime. Phys. Rev. B 93, 020504 (2016).

Proslier, T. et al. Probing the superconducting condensate on a nanometer scale. Europhys. Lett. 73, 962 (2006).

Ingold, G., Grabert, H. & Eberhardt, U. Cooper-pair current through ultrasmall Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 50, 395 (1994).

Chauvin, M. et al. Crossover from Josephson to multiple Andreev reflection currents in atomic contacts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 067008 (2007).

Jäck, B. et al. A nanoscale gigahertz source realized with Josephson scanning tunneling microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 013109 (2015).

Ast, C. R. et al. Sensing the quantum limit in scanning tunnelling spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 7, 13009 (2016).

Cuevas, J. C., Levy Yeyati, A. & Martín-Rodero, A. Microscopic origin of conducting channels in metallic atomic-size contacts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1066 (1998).

Cuevas, J. C. et al. Evolution of conducting channels in metallic atomic contacts under elastic deformation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 2990 (1998).

Averin, D. & Nazarov, Y. Coulomb fingerprints on the I–V curves of the normal tunnel junctions. Phys. B Condens. Mater. 162, 309 (1990).

Devoret, M. H. et al. Effect of the electromagnetic environment on the Coulomb blockade in ultrasmall tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 1824 (1990).

Averin, D., Nazarov, Y. & Odintsov, A. Incoherent tunneling of the cooper pairs and magnetic flux quanta in ultrasmall Josephson junctions. Phys. B Condens. Mater. 165-166, 945 (1990).

Muller, C. J., van Ruitenbeek, J. M. & de Jongh, L. J. Experimental observation of the transition from weak link to tunnel junction. Phys. C 191, 485 (1992).

Rodrigo, J. G., Agraït, N., Sirvent, C. & Vieira, S. Josephson current at atomic scale: tunneling and nanocontacts using a STM. Phys. Rev. B 50, 12788 (1994).

Scheer, E. et al. The signature of chemical valence in the electrical conduction through a single-atom contact. Nature 394, 154 (1998).

Scheer, E., Joyez, P., Esteve, D., Urbina, C. & Devoret, M. H. Conduction channel transmissions of atomic-size aluminum contacts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 3535 (1997).

DellaRocca, M. L. et al. Measurement of the current-phase relation of superconducting atomic contacts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 127005 (2007).

Cuevas, J. C., Martín-Rodero, A. & Levy Yeyati, A. Hamiltonian approach to the transport properties of superconducting quantum point contacts. Phys. Rev. B 54, 7366 (1996).

Andreev, A. F. The thermal conductivity of the intermediate state in superconductors. Sov. Phys. JETP 16, 1228 (1964).

Klapwijk, T. M., Blonder, G. E. & Tinkham, M. Explanation of subharmonic energy gap structure in superconducting contacts. Phys. B+C 109, 1657 (1982).

Cuevas, J. C. & Belzig, W. Full counting statistics of multiple Andreev reflections. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 187001 (2003).

Cuevas, J. C. & Belzig, W. DC transport in superconducting point contacts: a full-counting-statistics view. Phys. Rev. B 70, 214512 (2004).

Beenakker, C. W. J. Universal limit of critical-current fluctuations in mesoscopic Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 3836 (1991).

Nazarov, Y. & Blanter, Y. Quantum Transport: Introduction to Nanoscience (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2009).

Roychowdhury, A., Dreyer, M., Anderson, J. R., Lobb, C. J. & Wellstood, F. C. Microwave photon-assisted incoherent Cooper-pair tunneling in a Josephson STM. Phys. Rev. Appl. 4, 034011 (2015).

Assig, M. et al. A 10 mK scanning tunneling microscope operating in ultra high vacuum and high magnetic fields. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 84, 033903 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge fruitful discussions with Berthold Jäck and Elke Scheer. Funding from the European Research Council for the Consolidator Grant ABSOLUTESPIN (Grant No. 681164), from the Spanish MINECO (Grant No. FIS2014-55486-P, FIS2017-84057-P and FIS2017-84860-R), from the “María de Maeztu” Programme for Units of Excellence in R&D (MDM-2014-0377), from the Zeiss Foundation, from the DFG through AN336/11-1 and from the IQST is also gratefully acknowledged. J.C.C. and W.B. acknowledge support from the DFG through SFB 767.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.R.A., J.A., J.C.C., W.B. and K.K. initiated the project. J.S. measured the data with help of M.E. S.D., C.P., B.K. and J.A. provided the theory with support from A.L.Y., J.C.C., C.R.A., W.B., J.S. and R.D. C.R.A. and R.D. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Senkpiel, J., Dambach, S., Etzkorn, M. et al. Single channel Josephson effect in a high transmission atomic contact. Commun Phys 3, 131 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00397-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00397-z

This article is cited by

-

Determining the temperature of a millikelvin scanning tunnelling microscope junction

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Superconducting quantum interference at the atomic scale

Nature Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.