Abstract

Multispectral frequency combs provide new architectures for laser spectroscopy, clockwork, and high-capacity communications. Frequency microcombs have demonstrated remarkable impact in frequency metrology and synthesis, albeit with spectral bandwidth bounded by intrinsic second-order dispersion and consequently low-intensities at the spectral edges. Here we report coherent satellite clusters in multispectral regenerative frequency microcombs with enhanced intensities at the octave points and engineered frequency span. Beyond the conventional bandwidth of parametric oscillation, the regenerative satellites are facilitated by higher-order dispersion control, allowing for multiphase-matched parametric processes. The satellite span is deterministically controlled from 34 to 72 THz by pumped at C/L-bands, with coherence preserved with the central comb through the nonlinear parametric process. We further show the mirrored appearance of the satellite transition dynamics simultaneously with the central comb at each comb state. These multispectral satellites extend the scope of parametric-based frequency combs and provide a unique platform for clockwork, spectroscopy and communications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optical parametric processes serve as the fundamental mechanism for a variety of nonlinear optics phenomena and unique applications involving laser frequency combs1,2,3, squeezed state generation4,5, four-wave mixing with matter waves6, high-harmonic generation7, and Bose−Einstein condensation8. In the general context of optical parametric oscillation, achieving broadband frequency conversion is usually bounded by chromatic dispersion of the propagating medium and is, however, demanding for frontier applications that require wide coherent spectrum. In a parametric-based frequency microcomb, an overall comb bandwidth of an octave or two-third of an octave will allow for a self-referenced frequency stabilization through f-to-2f or 2f-to-3f carrier-envelope-offset (fCEO) technique9,10, which enables the precise definition of the comb line frequency without requiring an external optical reference. Realizing parametric oscillation in such broad bandwidth without post spectral broadening and with high nonlinear conversion efficiency is comparatively nontrivial in microresonators due to the limited degrees of freedom to control the cavity dispersion. Recently studied dissipative Kerr solitons (DKSs) in microresonators provide an elegant platform for broadband self-referenced combs assisted by dispersive wave11,12,13,14,15 and have achieved a full octave or a two-third-octave span. This has led to the successful implementation of 2f-3f self-referencing assisted by external laser sources10. This approach, however, still suffers from low comb powers at the octave points for harmonic (2f or 3f) generations and usually requires high-power transfer lasers to overcome the hyperbolic-secant intensity falloff bottleneck of frequency comb16. Dispersive wave at both the red- and blue-sides of the pump can be generated with engineered third-order dispersion aided by geometrical design15,17,18,19. Stimulated Raman scattering-based processes can amplify the comb intensity on the long-wavelength side effectively20,21,22, albeit without an assured frequency conversion on the short-wavelength side. Furthermore, multispectral coherent synthesis23,24 can successfully overcome the power-bandwidth paradox but requires multiple stages of lasers and frequency combs.

Most studied microcombs start with modulation instability (MI) and parametric four-wave mixing (FWM), leading to phase-correlated primary comb modes, followed by subcomb families generation21,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. The primarily phase-matched modes, spectrally determined by the local anomalous dispersion, nonlinear frequency shift and pump-resonance detuning, will shape the total bandwidth and general envelope of the overall comb spectrum. These primary modes and their subcombs are predominantly bounded by the second-order dispersion, striving for a near-zero or normal second-order dispersion for broadband clusters32,33 and multioctave parametric oscillation34. Quasi-phase-matching can also be introduced to compensate the phase mismatch through periodic dispersion control35, and recently single-crystalline microcavities have also observed octave-spanned FWM36,37.

Here we report a different modality in broadband multispectral frequency generation, through higher-order dispersion control in silicon nitride microcavities, which achieves regenerative coherent signal and idler satellite structures adjacent to the central frequency comb with higher-order phase-matching. Beyond the conventional phase-matching bandwidth, regenerative satellites are observed in the same microcavity: symmetric satellites with azimuthal cavity mode numbers (in the ≈100th−310th mode range) symmetric with respect to the coherent pump laser, along with dispersive waves with azimuthal cavity mode numbers (in the ≈350th−460th mode range) asymmetric from the pump. Efficient power conversions are observed from the pump to the satellites, on par with that from the pump to the primary intensity lines of the central comb. The symmetric satellite centroid locations match with our theoretical predictions and numerical modeling. With the high-intensity satellites and dispersive waves, the overall comb spectra can be in excess of an octave. Furthermore, we examine the dynamical evolution and mutual coherence of these regenerative satellites, via the laser-cavity detuning, through the correlated radio-frequency (RF) amplitude noise spectral densities of the satellites and central comb, and the instrument-limited 113.73-GHz equi-distance spacing across multiple spectral bands of the satellites (O-band) and the central comb (C-band). Via internal modulation instability in each satellite, secondary satellites can be observed through MI process from satellite centers. The multiphase-matched regenerative satellite combs can serve as promising platforms for ultra-broadband coherent communications, self-referenced frequency combs, and multispectral precision sensing and spectroscopy.

Results

Frequency microcombs with satellite clusters and dispersive waves

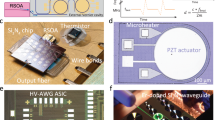

Figure 1 shows a series of measured frequency combs with regenerative satellites under coupled pump power range of 28.5−31.5 dBm for different pump laser-cavity detunings. The devices under investigation are silicon nitride microrings with measured loaded quality factor (Q) of ≈950,000, and ring-waveguide cross-sections of 1600 × 800 nm2 (Fig. 1a–f) and 1500 × 800 nm2 (Fig. 1g). The device fabrication process is detailed in the Methods section. The inset of Fig. 1a shows a scanning electron micrograph of the ring cavity. In this 400 µm diameter ring cavity, the waveguide-cavity coupling is tuned to near critical coupling, with a nearly single-mode family of transverse magnetic polarization (TM11) across the entire pump wavelength range. The measured free spectral range (FSR) is ≈113.9 GHz under cold cavity conditions. On the blue- and red-sides of the central comb ≈1425−1800 nm of Fig. 1a–f, strong intensity satellite clusters—highlighted in the dashed boxes—are simultaneously observed and even with intensities as high as the central comb. With proper dispersion profile in a slightly different geometry and assisted by dispersive wave generation, the clusters can span close to one full octave or even larger, as shown in Fig. 1g.

Example spectra of multiphase-matched frequency comb with both satellite comb and dispersive wave (DW) together with the central comb, pumped at: a 1576.615 nm, b 1581.881 nm, c 1584.704 nm, and f 1596.238 nm with coupled power of 30.5 dBm. Multiphase-matched satellite comb pumped at: d 1592.401 nm and e 1595.133 nm with coupled power of 28.5 dBm. Two-third octave span with the satellite clusters are achieved in (d) and (e). g Close-to-one-octave spanning comb pumped at 1581.73 nm, with two satellite centroids located at 1186.48 and 2371.89 nm. The signal-idler satellite centroids overlap within an FSR when the idler satellite is frequency doubled. Inset of (a), scanning electron micrograph of the microcavity frequency comb, with 400 µm silicon nitride ring diameter and 1600 × 800 nm2 width-height cross-section. Scale bar: 100 µm. The microcavity used in (g) is with slightly different width-height cross-section of 1500 × 800 nm2. The comb mode numbers of the satellites and dispersive waves (DW) are labeled in each panel.

Consequently, the intracavity phase mismatch per round trip (Δωm) can be described as Δωm = ωm + ω−m − 2ωo, where the pump frequency is denoted as ωo, the signal and idler satellites as ωm and ω–m respectively, with m the azimuthal mode number of TM11 mode family. Here we calculate the primarily phase-matched signal and idler resonance pair, from which the adjacent cascaded comb modes are derived. Conventionally, the central frequency comb is spectrally bounded by MI bandwidth. The intracavity phase mismatch Δωm gradually reaches to zero when the phase shift introduced by the cavity dispersion balances that induced by the intracavity nonlinearity. The case where Δωm reaches zero denotes the recent Kerr frequency combs observed to date, which is initiated primarily by parametric modulation instability wherein the second-order dispersion dominates in phase-matching, with its corresponding gain bandwidth. We denote this as the central comb for clarity in Fig. 1. If the higher even-order dispersion is positive and large enough, however, and able to inversely balance the phase mismatch induced by second-order anomalous dispersion, phase matching (Δωm = 0) is also possible with a sufficiently large accumulated azimuthal mode number32. This results in a phase-matching bandwidth in these mode numbers significantly larger than the intrinsic modulation instability gain bandwidth. In the case where the signal and idler cavity mode numbers are symmetric, with equal integer magnitude offset (±) from the pump, and energy conservation of the signal and idler photons are preserved (ωm + ω−m = 2ωo), we can denote these as the satellites. An analytical consideration of satellite phase-matching conditions is detailed in Methods.

The strong intensity satellites—on the blue- and red-sidebands of the central frequency comb—of Fig. 1a corresponds to that of a symmetric satellite comb. In this microcavity, the higher-order dispersion is chosen to be large to support the phase-matching setting. Figure 2a plots the measured group velocity dispersion (GVD), mapped with a Mach-Zehnder-clocked swept-wavelength interferometer (detailed in Methods and ref. 27) in comparison with the modeled dispersion. Figure 2b illustrates the corresponding accumulated cavity phase mismatch of our ring cavity versus mode number. First, at the zero phase match points, the MI-induced phase-matched modes are illustrated in the gray dashed box regions, corresponding also with the central comb structure in Fig. 1. Second, with the anomalous dispersion of our ring cavity, the cavity phase match increases initially for increasing mode numbers (up to m ≈ 200, in this cavity) but folds back towards the zero phase mismatch point again at mode numbers m ≈ 290. This is illustrated in the black dashed box. Particularly, in this region, symmetric satellites can potentially also be observed. Thirdly, the horizontal red lines denote the 1 × FSR (m) and 2 × FSR (m) phase-matching that can lead to asymmetric paired comb line formation, reminiscent of Faraday instabilities35,38. These asymmetric (m + 1) and asymmetric (m + 2) cavity phase-matched regions are denoted in Fig. 2b, potentially enabled by the inherent large higher-order dispersion of this cavity with quasi-phase matching design.

a Modeled group velocity dispersion (GVD; green solid curve) and third-order dispersion (TOD; blue dashed curve). Zero dispersion is plotted in green dashed line. Inset: measured GVD by swept wavelength interferometry (red dot) with fitting uncertainty plotted as error bar, along with numerical modeling support (blue solid curve). b Analytical cavity phase mismatch as a function of azimuthal mode number m, \({\mathrm{\Delta }}\omega _m = \omega _m + \omega _{ - m} - 2\omega _0\), with symmetric satellite comb phase-matching highlighted in black box and asymmetric highlighted in orange box. Highlighted stars are experimentally measured comb number of the satellite centroids pumped at 1576.615 nm (blue), 1581.881 nm (magenta) and 1584.704 nm (green) with coupled powers of 30.5 dBm. Due to the large positive fourth-order dispersion (FOD, β4), phase-matching occurs simultaneously at multiple spectral ranges, leading to the satellite comb families at O-band and ≈ 2 μm as shown in Fig. 1a–c. With the large FOD, the residual dispersion folds backwards, leading to the formation of symmetric satellite combs. If the residual dispersion equals one cavity FSR, parametric oscillation may generate comb mode at (m + 1), (m + 2), or even the (m + n)th cavity mode, leading to the potential formation of the asymmetric satellite combs. c Zoom-in view of black box in panel (b). Theoretically calculated phase-matching curves for symmetric satellites, along with the measured satellite centroid position illustrated as datapoints (stars with the same colors).

Figure 2c illustrates a zoom-in of the cavity phase-matching around the 250th−295th azimuthal cavity modes. With the measured FSR, the accumulated dispersion crosses zero at the 291st ± 1 mode for the measurement at 1576.615 nm pump and 30.5 dBm coupled power (blue line). This is the symmetric satellite comb shown in Fig. 1a. Adjusting the pumped resonances, Fig. 1b, c shows the corresponding symmetric satellite spectra for the pump at 1581.881 and 1584.704 nm, with 30.5 dBm coupled power. The intensity-weighed centroids of the satellites are illustrated as magenta and green stars in Fig. 2c. Note that from the experiments, the intensity-weighed centroids are close to the primarily phase-matched positions as analyzed in the theory above, with difference of less than three modes from the intracavity power change due to the detuning adjustment. The effective adjustment of satellites span via pump mode can be understood by perturbation theory applying within the same pumping resonance. One can therefore denote the perturbed frequency of the pump, intensity-weighed centroid frequencies of signal satellite and idler satellite as δωo, δωm and δω−m. Momentum conservation of the satellite centroid frequencies holds as: δωm GVm + δω−m GV−m = 2δωo·GVo, where GVi represents the group velocity of the ith azimuthal mode. Together with energy conservation δωm + δω−m = 2δωo, this can be readily rewritten as:

The left-hand side of Eqs. (1) and (2) represent the tunability slope of signal-idler satellite centroids at the given pumping mode δωo. The phase-matched azimuthal mode number m can be calculated as described in Fig. 2a, which is related to dispersion profile at δωo; hence, the right-hand side of the equations indicates this tunability is determined by the higher-order dispersion. Plugging into the group velocity values, the tunability is in the range of 3−5 pumped at 1570−1590 nm for the device majorly investigated in this work, agreeing with the series of measurements on satellite comb spectra (shown in Fig. 3). Looking into the right-hand side of (1) and (2) further by expanding the group velocity of signal and idler from the pump:

where Ω is the spectral shift, \({\mathrm{\Omega }} = {\upomega}_{\mathrm{m}} - \omega _0 = \omega _0 - \omega _{ - m}\), and βi,0 (i = 2, 3) represent the ith-order dispersion terms at pump wavelength, neglecting contribution from higher-order dispersion. Hence, Eqs. (1) and (2) can be expressed as:

a, b Zoomed-out frequency comb spectra pumped at the same resonance mode with different detunings (Δ1 = 1581.70 nm and \(\Delta _1^\prime\) = 1581.88 nm; L-band), with coupled power of 30 dBm. Inset of (a), Pump-cavity transmission as a function of pump wavelength, illustrating the detunings where different satellite comb stages are generated. With more power loaded into the cavity, the intensity-weighed satellite centroid shifts by 1 or 2 cavity modes close to pump due to the increased nonlinear phase shift from higher intracavity power. c, d Zoom-in of the ≈1350 and 1900 nm satellite combs generated when pumped at different resonance modes in the L-band. The vertical axis is the pump wavelength and the horizontal axis is the satellite comb spectra. The comb mode numbers of the satellite centroid are labeled in each panel. Dispersive waves (DW) are observed when pump wavelength is larger than 1585 nm.

Therefore, this slope only depends on \(\frac{{\beta _{3,0}}}{{\beta _{2,0}}}\), given the spectral shift of satellite, the former determined by \({\mathrm{\Omega }}^2 = - \frac{6}{{\beta _4}}( {\beta _2 - \sqrt {\beta _2^2 - \frac{{4\beta _4\gamma P}}{3}} } )\) (see Methods for details). Hence by approximation \(\frac{{\delta \omega _m - \delta \omega _0}}{{\delta \omega _0}} \approx - \frac{{\beta _{3,0}{\mathrm{\Omega }}}}{{3\beta _{2,0}}} \approx - \frac{{2\beta _3}}{{\sqrt { - 3\beta _2\beta _4} }}\) is a function of dispersion terms at pump mode. In optical microresonators, this tunability can be designed by waveguide geometry control. The symmetric satellite comb structure is supported by numerically modeling, with examples for Fig. 1a, d shown in Supplementary Note 1. Dependence of phase-matching on higher-order dispersion for the symmetric satellites is shown in Supplementary Note 2.

Figures 1d–f show the same microresonator under different pump wavelengths and pump powers, wherein dispersive waves are observed simultaneously with the satellite clusters. These comb clusters are highlighted in the brown, orange and purple boxes for illustration. In Fig. 1d the satellites closest to the central comb, at ≈1.415 and 1.820 μm, are from symmetric phase-matching. The further-spaced dispersive waves at ≈1.303 and 1.955 μm are asymmetric with respect to pump. We note that, even with the dispersive waves extending over two-third of an octave, the peak intensities of the satellites can reach up to −15 dBm—on the same order-of-magnitude intensity as the central comb. Since our output intensity collection is unoptimized over such a large (77 THz) frequency range including cavity-to-waveguide coupling and objective lenses, the intensity of the satellites in the collected Fig. 1 spectra should be even higher than −15 dBm. Slightly changed geometric design of the microring leads to a slightly different dispersion profile (simulation comparison shown in Supplementary Note 3), allowing the spanning of microcomb clusters to be an octave (Fig. 1g). The high conversion efficiency at the octave points could potentially benefit the f-2f self-referenced stabilization application, with greatly reduced power budget.

Satellite comb structure under different driving conditions

The primary lines of satellite clusters are generated simultaneously with the primary lines of the central frequency comb and define the fundamental structure of the regenerative frequency combs. This is shown in Fig. 3a, b, where we plot the comb structures driven at the same resonance mode, but with slightly different detunings at 1581.70 nm (denoted as Δ1) and 1581.88 nm (denoted as \(\Delta _1^\prime\)). We note that the satellites grow simultaneously with the primary lines of the central comb, and the primary lines of Fig. 3a shape the basic structure of the fully developed satellite and the central combs shown in Fig. 3b. Efficient power conversion is achieved from the pump to the satellite sidebands, with the satellite primary intensity close to primary lines of the central comb (Fig. 3a) and the fully defined structure (Fig. 3b), even with an unoptimized broadband collection setup. Within the same resonance mode (inset of Fig. 3a shows the 1581.70 and 1581.88 nm relative detunings), a fully developed satellite can span over 536 modes, equivalently to ≈61 THz, simultaneously with a fully developed central comb.

The span of signal-idler symmetric satellite centroids, as analyzed in Eqs. (1) and (2), can be practically controlled by varying the pumping resonances. This can be seen by zooming into the fully developed signal and idler satellites, as shown in Fig. 3c, d, under a broad pumping regime from 1570 to 1590 nm at 30.0 dBm coupled pump power. We observe and verify that the satellite combs have a symmetric spectral separation of the signal and idler satellites, with respect to each pump mode. This confirms the codependence of satellites at blue- and red-sides and the physical basis from signal-idler energy conservation. The magnitude of this signal-idler spectral span is deterministically tuned by the pump wavelength, different from Raman-induced combs20 which has a phonon-defined vibrational frequency offset. Signal-to-idler satellite centroids span from 54 THz (464 nm) to 71 THz (604 nm) under this pump condition in this resonator. In a different resonator with slightly varied dispersion, assisted by dispersive wave, the span of the satellite centroids can achieve more than one octave, or even a close to one-octave span of ≈126.4 THz as shown in Fig. 1g, with the short- and long-wavelength dispersive wave peaks reaching 1.2 and 2.4 µm respectively. In Fig. 3c, d, the satellite comb spectra pumped at below 1585 nm wavelengths arise from symmetric family and the spectral shift is observed with a scaling of 3−5 satellite azimuthal modes per pump mode, agreeing well with our theoretical estimates in Eqs. (1) and (2).

The simultaneous occurrence of both symmetric satellites and dispersive waves can be observed in this microcavity when the pump wavelength is longer than 1585 nm. The dispersive waves are plotted in Fig. 3c, d as well. Within our ring cavity, the dispersive waves achieve an even larger bandwidth—of 79 THz pumped at 1586.41 nm—compared to symmetric satellites. We also note that the intensity-weighted centroid of the satellite can shift within ±1 mode due to intracavity power changes from detuning adjustment, in a similar manner with the primary modes of the central comb and observed throughout all the pumping modes (e.g. positions of satellite centroids shift by one mode from Fig. 3a, b). Furthermore, in the central comb when pumped at 1581.88 nm (Fig. 3b), the red-side shows more modes and higher intensity, attributable to dispersive wave (DW) due to the large third-order dispersion in our cavity. Examples of the satellite combs with the different DW peaks are detailed in Supplementary Note 4 when pumped at a different spectral region of ≈1561.40 nm, where the ratio of second- and third-order dispersion is larger for the same cavity. This DW spectral broadening, however, is still smaller than the symmetric and potentially asymmetric satellite comb spans.

Observed summary of satellite map versus theoretical comparison

The multiphase-matched theory is well-supported by a series of experiments shown in Fig. 4a. Under different detunings and on-chip powers (different colored squares), the phase-matched symmetric satellites fall into different spectral locations, agreeing with the theoretical model predictions (black solid curves) over the 140 experimental measurement datasets. Note that the tunability shown from the simulation is close to the measurement, since this tunability mainly depends on the ratio of TOD and GVD (from the analysis above on symmetric satellites), whose value is close between simulation and real measurement. Meanwhile, modeling for dispersive waves (green dashed curves) matches with the observations (different colored triangles) with uncertainty, resulting from the uncertainty of refractive index and higher-order dispersion. We also note that both symmetric satellite and dispersive wave can exist under the same pump mode. In Fig. 4b, c, we illustrate such an example pumped at the same resonance while with a slightly different detuning of 80 pm. This effect is observed in numerical simulations detailed in Supplementary Note 1, where the satellite sidebands can disappear and reappear as the detuning continues to grow.

a Satellite maps for different pump wavelengths, including parameter sets for three varied coupled pump powers. Under different pump powers and detunings, exchange between symmetric satellite (s-sat) and dispersive wave (DW) is observed. Theoretical analysis for symmetric satellites (black solid lines) matches well with our measurements. Modeling for dispersive waves (green dashed lines, DW1 and DW2) match with our measurements with uncertainty resulting from the uncertainty of higher-order dispersion and refractive index. An example of the symmetric satellite (s-sat) and dispersive wave (DW) is shown in (b, c) where the resonator is pumped under the same mode but with slightly different detuning. The comb mode numbers of the symmetric satellite and dispersive waves are labeled.

Coherence transfer and regeneration with dynamical evolution

One advantage of the parametric process is the coherence transfer and regeneration. This will potentially lead to a regeneration of dynamical evolution in the multispectral structures, in various spectral regimes that are phase-matched. Figure 5a examines the evolution of the signal satellite and their corresponding RF amplitude noise spectral density, with laser-cavity detunings up to 103 pm in the same pump mode, revealing the regenerative evolving dynamics between the signal satellite and the central comb. With pump detuned into the resonance, the satellite first starts with low-noise primary lines (Fig. 5a, b) with the central comb also in the low-noise state as shown in the right panel of Fig. 5a. When the subcomb lines begin to evolve (stage c), a pristine beat note of 46.0 MHz with its harmonic is observed in the satellite (black curve). Simultaneously, when optically filtering and collecting only the central comb, an instrument-limited identical 46.0 MHz beat note is also observed (green curve). In the central frequency comb, the 46.0 MHz beat note arises from the subcomb families, which in turn comes from mismatch between the MI-induced phase-matching and local FWM. Our observation of the same 46.0 MHz beat note in the satellite verifies the same underlying mechanism, of the mismatch between MI-induced phase-matching and local FWM, arising in the signal satellite combs. The correlated RF noise spectrum between the satellite and central comb provides evidence on mutual coherence across the overall optical spectrum. By detuning the pump deeper into resonance, a self-injection locked state for both the satellite and the central comb is observed. This results in the low-noise coherent state comb (Fig. 5d). As the detuning increases further, the satellite becomes broader and transits to high-noise states (Fig. 5e). The idler satellites, detailed in Supplementary Note 5, also show matching coherence transition and RF evolution as the signal satellites. Besides, our measurements further support a matching coherence evolution of the short-wavelength dispersive wave (substantiated in Supplementary Note 5), in accordance with the symmetric satellites. In the generation of the satellites, coherent satellites with two FSR spacing, high-noise satellites with single FSR spacing, as well as with self-injection locking, can be observed in our measurements through control of the laser-cavity detuning.

a–j Evolution dynamics of the symmetric satellites. a–e Series of satellite spectra with step-wise detuning over 103 pm. The dashed orange boxes denote the secondary satellites within each satellite. f–j Corresponding RF amplitude noise measurement. Black and green curves plot for the satellites and the central comb respectively, the latter measured through filtered ≈50 nm bandwidth around 1550 nm. Red curve in (f) plots the detector background noise. Both satellite and central comb start with low-noise primary lines as shown in a, f, b, g. With detuning increases (panel c), an instrument-limited identical beat note of ≈46.0 MHz can be found between the satellite (black) and central combs (green) as shown in panel (h). By further detuning the pump, a self-injection locked state is achieved, forming a mutually coherent comb (d), resulting in a measured low amplitude noise as shown in panel (i). With the detuning further increasing, the comb transits to a high-noise state as shown in (e) and (j). k Two consequent processes in satellite formation. (I) Degenerate four-wave mixing (FWM) in forming the conventional modulation-instability-induced comb modes and central lines of the satellites; and (II) satellite evolution generated from nondegenerate FWM from the strong pump, comb modes in the vicinity of pump, and the central lines of the satellites. Process (II) ensures the coherence transfer from the central comb to the satellites, leading to mutual comb spacing between these comb clusters. l Evidence of coherence transfer. An identical averaged 113.730 GHz comb spacing is experimentally measured across the central comb at C-band and the signal satellite at O-band, with error bars plotted for the standard deviation of comb spacing at each comb mode.

The secondary satellites are observed in the symmetric cluster formation, highlighted in the orange dashed boxes of Fig. 5a–e. Taking the symmetric satellite centered at 1362.5 nm as example (Fig. 5a), with the simulated GVD, TOD and FOD of −82.6 fs2/mm, 4.1 fs3/mm and 1806 fs4/mm respectively, the parametric process at 1362.5 nm only supports conventional MI without satellite phase-matching, leading to the formation of secondary satellites. Consequently, the satellites aside from the secondary satellites are generated via the nondegenerate FWM from two central comb frequencies and the satellite centroid, rather than the degenerate FWM of MI—the former process has higher nonlinear conversion efficiency compared to the latter. This again indicates that the satellite modes, aside from the secondary satellites, are seeded from the central frequency comb and holds spectral correlation.

With these, Fig. 5k illustrates the overall parametric process with regards to the satellite formations with coherence transfer and regeneration. Two main simultaneous processes are involved in the satellite evolution: (I) degenerate FWM in forming the conventional MI-induced comb modes, central lines of satellite combs and the secondary satellites when phase-matched; followed by (II) satellite evolution generated from nondegenerate FWM from the strong pump, comb modes near the pump and the central line of the satellite. Process (I) defines the fundamental structure of the regenerative frequency comb and process (II) ensures the coherence transfer from the central comb to the satellites, leading to regeneration of comb evolution and comb spacing between these comb satellites. To further support this framework, we conduct a line-to-line measurement of the regenerative satellite and the central comb across the whole spectrum in a mutually coherent state, determining the 113.730 GHz mode spacing in the O-band at the 5 × 10−5 level (≈6 MHz) via a high-precision wavelength meter. We filter each comb mode out with a 1-nm tunable bandpass filter and lock the pump laser to a 1-Hz laser. The wavelength meter has 60-MHz precision, while enabling a mode-to-mode FSR spacing precision of 60-MHz/n, where n is the comb mode number away for the pump. This approach also allows the line-to-line measurement at the O-, C- and L-bands from the same instrument. Figure 5l shows several measured comb spacings across the O- and C-band. Both the satellite and the central comb verify an averaged mode-to-mode spacing of 113.730 GHz with an instrument-limited standard deviation of 6 MHz for the satellite (890 kHz for central comb). This further supports a coherence transfer between the satellite and the central frequency comb at the instrument limit, in the existence and formation of the multiphase-matched satellites.

Discussion

In this work we report the formation of coherent satellites in multispectral regenerative frequency microcombs based on the higher-order dispersion control, in the azimuthal-mode-number symmetric configurations and assisted by dispersive waves, spanning in excess of two-thirds of an octave. Within the same pump resonance mode, fully developed low-noise signal and idler satellites can span up to two-third octave, simultaneously with a fully developed low-noise central comb. Symmetric satellite phase-matching is examined in detail, with a tunability of 3−5 satellite modes per pump mode. Coexistence of the symmetric satellite and dispersive wave, along with their exchange, is observed while the signal-to-idler cluster centroids can span more than an octave. Secondary satellites are observed, arising from internal modulation instability at each satellite. Examined robustly over 140 satellite structures, the experimentally observed satellite positions find good match with the theoretical modeling, along with the influence of fourth-order dispersion uncertainties. Mutual coherence between the comb clusters is achieved through nondegenerate four-wave-mixing, validated through the correlated RF beat notes and low-noise power spectral densities in the dynamical evolution, and through the instrument-limited equi-distance spacings between the satellites and the central comb. The studies on multispectral and broadband satellites expand the realm of parametric-based nonlinear processes, and provide an exceptional chip-scale broadband optical frequency comb source, a suitable platform for self-frequency-referenced oscillator synthesis, and modular precision spectroscopy and sensing in multispectral regimes.

Methods

Silicon nitride cavity nanofabrication

First, a 3-μm-thick SiO2 layer is deposited via plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) on p-type 8″ silicon wafers to serve as the under-cladding oxide. Then low-pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD) is used to deposit an 800 nm silicon nitride for the ring cavity resonators, with a gas mixture of SiH2Cl2 and NH3. The resulting silicon nitride layer is patterned by optimized 248 nm deep-ultraviolet lithography and etched down to the buried SiO2 via optimized reactive ion dry etching. Then the silicon nitride cavities are annealed at 1200 °C to reduce the N-H overtones absorption at the shorter wavelengths. Finally, the silicon nitride cavities are over-cladded with a 3-μm-thick SiO2 layer, deposited initially with LPCVD (500 nm) and then with PECVD (2500 nm). The propagation loss of the Si3N4 waveguide is ≈0.2 dB/cm at the pump wavelength.

Mach−Zehnder-clocked swept-wavelength interferometry

The cavity transmission was recorded when the laser was swept from 1550 to 1630 nm at a tuning speed of 40 nm/s. The sampling clock of the data acquisition is derived from the photodetector monitoring the laser transmission through a fiber Mach−Zehnder interferometer with 40 m unbalanced path lengths, which translates to a 5 MHz optical frequency sampling resolution. Transmission of the hydrogen cyanide gas cell was simultaneously measured and the absorption features were used for absolute wavelength calibrations. Each resonance was fitted with a Lorentzian lineshape to determine the resonance frequency and the quality factor. The cavity dispersion was then calculated by analyzing the wavelength dependence of the free spectral range.

Analysis on phase-matching conditions for the symmetric satellites

The parametric gain reaches maxima at the condition as36,39: \(\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{{{k}} \ge 1} {\frac{{{{\beta }}_{2{{k}}}}}{{\left( {2{{k}}} \right)!}}} {{\Omega }}^{2{{k}}}{{L}} + 2{{\gamma }}{{PL}} - {\mathbf{\delta }}_0 = 0,\) where Ω is the sideband frequency shift, L is the cavity length, and P is the intracavity power. Considering up to fourth-order dispersion \(\frac{{{{\beta }}_4}}{{24}}{{\Omega }}^4 + \frac{{{{\beta }}_2}}{2}{{\Omega }}^2 + 2{{\gamma }}{{P}} = 0\), this leads to the following expression for the spectral shift \({{\Omega }}_{{s}}:{{\Omega }}_{{s}}^2 = - \frac{6}{{{{\beta }}_4}}\left( {{{\beta }}_2 \pm \sqrt {{{\beta }}_2^2 - \frac{{4{{\beta }}_4{{\gamma }}{{P}}}}{3}} } \right)\). Different from the previously reported FWM, where β2 > 0 and β4 < 0, here in our work β2 < 0 and β4 > 0 and hence intracavity power P must be below \(\frac{{3{{\beta }}_2^2}}{{4{{\beta }}_4{{\gamma }}}}\). There are two solutions for \({{\Omega }}_{{s}}^2,\) and particularly at the extreme point where P equals \(\frac{{3{{\beta }}_2^2}}{{4{{\beta }}_4{{\gamma }}}}\) the two solutions are equal. We note that the term \(\frac{{4{{\beta }}_4{{\gamma }}{{P}}}}{3}\) cannot be neglected when intracavity power P is sufficiently large due to cavity enhancement. A cavity finesse F of ≈600 in this situation corresponds to a power enhancement factor of 95.5. Under mean field and good cavity approximation, this can be simplified to \({{\Omega }}_{{s}}^2 = - \frac{{12{{\beta }}_2}}{{{{\beta }}_4}}\)36.

Dependence of phase-matching on higher-order dispersion

Taking the first-order partial derivative of \({\mathrm{\Omega }}_{{s}}^2\) with respect to β4, we get the following expression: \(\frac{{\partial {\mathrm{\Omega }}_{{s}}^2}}{{\partial \beta _4}} = \frac{{6\beta _2}}{{\beta _4^2}} \mp \frac{6}{{\beta _4^2}}\sqrt {\beta _2^2 - \frac{{4\gamma P\beta _4}}{3}} \pm \frac{{4\gamma P}}{{\beta _4\sqrt {\beta _2^2 - \frac{{4\gamma P\beta _4}}{3}} }}\). Under the mean field and good cavity approximation, we can obtain a relationship \(\frac{{\partial {\mathrm{\Omega }}_{{s}}^2}}{{\partial \beta _4}} \approx \frac{{12\beta _2}}{{\beta _4^2}}\). This indicates the dependence of spectral shift of the gain on positive fourth-order dispersion, i.e., decreasing β4 increases the spectral shift and vice versa.

Satellite dynamics measurements

To perform the satellite comb formation, the high-Q microcavity is pumped by a continuous-wave tunable laser followed by an optical amplifier (BkTel THPOA-SL, L-band; IPG EAD-3K-C, C-band), and a polarizer is employed to guarantee the input beam is TM polarized. In our microcavities, the coupling gap is designed to have nearly critical coupling for fundamental TM mode (TM11) and weak coupling for the second-order mode (TM21) across pump wavelength at 1550−1620 nm. This ensures the microcavity waveguide can be treated as single-mode operation for TM comb generation. The output comb spectrum is analyzed in both optical domain by optical spectrum analyzers (Yokogawa AQ6375, Advantest Q8384) and RF domain by an electronic spectrum analyzer (Agilent E4402B). Free-spaced filters, WDM filters and tunable O-band filter are used to select the focused O-band, C-band and 2-μm spectral ranges for analysis. Two cascaded O-band WDM fiber filters can realize a suppression ratio of more than 60 dB at C-/L-band, enough to suppress the strong pump and the nearby comb lines in order to analyze the O-band spectra only. A long-pass filter cutoff at 1550 nm and bandpass filters centered at 2000 or 2250 nm effectively select idler satellite comb beyond 1900 nm. An InGaAs photodetector (Newport 1611FC-AC, 1 GHz bandwidth, responsive from 900 to 1700 nm) is used to measure the amplitude noise of the signal satellite comb and central comb below 1700 nm. An extended InGaAs photodetector (Newport 818-BB-51F, 12.5 GHz bandwidth, responsive from 830 to 2150 nm) is used for measuring idler satellite comb.

Line-to-line measurement of the satellite and central comb

A high-precision wavelength meter (Bristol-821) is used to measure the wavelengths of the selected frequency lines. Each comb mode is individually filtered out by tunable bandpass filters with 1 nm linewidth (JDSU TB9 covering C-band and Agiltron FOTF-3-1 covering O-band). The pump laser is phase-locked to a Menlo fiber frequency comb, referenced to an ultrastable Fabry-Perot cavity (Stable Laser System), with an instantaneous linewidth close to 1 Hz. The schematic setup is shown in Supplementary Note 6. The majority of the measurement imprecision comes from variations of cavity FSR and the pump-cavity detuning. The former leads to the drift of comb spacing and the latter changes comb spacing in a linear manner40. With the chip temperature passively stabilized, the variation of cavity FSR is dominated by ambient noise, which can be in the hour time-scale. This measurement approach is bounded only by the precision of the wavelength meter41. To reduce the measurement imprecision, we limit the measurement duration to a few minutes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Pasquazi, A. et al. Micro-combs: a novel generation of optical sources. Phys. Rep. 729, 1–81 (2018).

Kippenberg, T. J., Gaeta, A. L., Lipson, M. & Gorodetsky, M. L. Dissipative Kerr solitons in optical microresonators. Science 361, eaan8083 (2018).

Gaeta, A. L., Lipson, M. & Kippenberg, T. J. Photonic-chip-based frequency combs. Nat. Photonics 13, 158–169 (2019).

Wu, L.-A., Xiao, M. & Kimble, H. J. Squeezed states of light from an optical parametric oscillator. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 4, 1465–1475 (1987).

Dutt, A. et al. Tunable squeezing using coupled ring resonators on a silicon nitride chip. Opt. Lett. 41, 223–226 (2016).

Deng, L. et al. Four-wave mixing with matter waves. Nature 398, 218–220 (1999).

Schafer, K. J., Gaarde, M. B., Heinrich, A., Biegert, J. & Keller, U. Strong field quantum path control using attosecond pulse trains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 023003 (2004).

Campbell, G. K. et al. Parametric amplification of scattered atom pairs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 020406 (2006).

Jones, D. J. et al. Carrier-envelope phase control of femtosecond mode-locked lasers and direct optical frequency synthesis. Science 288, 635–639 (2000).

Brasch, V., Lucas, E., Jost, J. D., Geiselmann, M. & Kippenberg, T. J. Self-referenced photonic chip soliton Kerr frequency comb. Light Sci. Appl. 6, e16202 (2017).

Brasch, V. et al. Photonic chip-based optical frequency comb using soliton Cherenkov radiation. Science 351, 357–360 (2016).

Obrzud, E., Lecomte, S. & Herr, T. Temporal solitons in microresonators driven by optical pulses. Nat. Photonics 11, 600–607 (2017).

Yang, Q.-F., Yi, X., Yang, K. Y. & Vahala, K. Counter-propagating solitons in microresonators. Nat. Photonics 11, 560 (2017).

Lucas, E., Guo, H., Jost, J. D., Karpov, M. & Kippenberg, T. J. Detuning-dependent properties and dispersion-induced instabilities of temporal dissipative Kerr solitons in optical microresonators. Phys. Rev. A 95, 043822 (2017).

Li, Q. et al. Stably accessing octave-spanning microresonator frequency combs in the soliton regime. Optica 4, 193–203 (2017).

Telle, H. R. et al. Carrier-envelope offset phase control: a novel concept for absolute optical frequency measurement and ultrashort pulse generation. Appl. Phys. B 69, 327–332 (1999).

Bao, C. et al. High-order dispersion in Kerr comb oscillators. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 34, 715–725 (2017).

Yi, X. et al. Single-mode dispersive waves and soliton microcomb dynamics. Nat. Commun. 8, 14869 (2017).

Yu, S.-P. et al. Tuning Kerr-soliton frequency combs to atomic resonances. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 044017 (2019).

Yang, Q.-F., Yi, X., Yang, K. Y. & Vahala, K. Stokes solitons in optical microcavities. Nat. Phys. 13, 53 (2017).

Cherenkov, A. V. et al. Raman-Kerr frequency combs in microresonators with normal dispersion. Opt. Express 25, 31148–31158 (2017).

Liu, X. et al. Integrated High-Q crystalline AlN microresonators for broadband Kerr and Raman frequency combs. ACS Photonics. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.7b01254 (2018).

Huang, S.-W. et al. High-energy pulse synthesis with sub-cycle waveform control for strong-field physics. Nat. Photonics 5, 475 (2011).

Manzoni, C. et al. Coherent pulse synthesis: towards sub-cycle optical waveforms. Laser Photonics Rev. 9, 129–171 (2015).

Ferdous, F. et al. Spectral line-by-line pulse shaping of on-chip microresonator frequency combs. Nat. Photonics 5, 770–776 (2011).

Herr, T. et al. Universal formation dynamics and noise of Kerr-frequency combs in microresonators. Nat. Photonics 6, 480–487 (2012).

Huang, S.-W. et al. Mode-locked ultrashort pulse generation from on-chip normal dispersion microresonators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 053901 (2015).

Huang, S.-W. et al. A low-phase-noise 18 GHz Kerr frequency microcomb phase-locked over 65 THz. Sci. Rep. 5, 13355 (2015).

Cole, D. C., Lamb, E. S., Del’Haye, P., Diddams, S. A. & Papp, S. B. Soliton crystals in Kerr resonators. Nat. Photonics 11, 671 (2017).

Yao, B. et al. Gate-tunable frequency combs in graphene–nitride microresonators. Nature 558, 410–414 (2018).

Yi, X., Yang, Q.-F., Yang, K. Y. & Vahala, K. Imaging soliton dynamics in optical microcavities. Nat. Commun. 9, 3565 (2018).

Matsko, A. B., Savchenkov, A. A., Huang, S.-W. & Maleki, L. Clustered frequency comb. Opt. Lett. 41, 5102–5105 (2016).

Sayson, N. L. B. et al. Origins of clustered frequency combs in Kerr microresonators. Opt. Lett. 43, 4180–4183 (2018).

Liang, W. et al. Miniature multioctave light source based on a monolithic microcavity. Optica 2, 40–47 (2015).

Huang, S.-W. et al. Quasi-phase-matched multispectral Kerr frequency comb. Opt. Lett. 42, 2110–2113 (2017).

Sayson, N. L. B. et al. Octave-spanning tunable parametric oscillation in crystalline Kerr microresonators. Nat. Photonics https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-019-0485-4 (2019).

Fujii, S. et al. Octave-wide phase-matched four-wave mixing in dispersion-engineered crystalline microresonators. Opt. Lett. 44, 3146–3149 (2019).

Tarasov, N., Perego, A. M., Churkin, D. V., Staliunas, K. & Turitsyn, S. K. Mode-locking via dissipative Faraday instability. Nat. Commun. 7, 12441 (2016).

Agrawal, G. (ed.) Nonlinear Fiber Optics (Fifth Edition) 397–456 (Academic Press, 2013).

Huang, S.-W. et al. A broadband chip-scale optical frequency synthesizer at 2.7 × 10−16 relative uncertainty. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501489 (2016).

Lv, X. et al. Generation of optical frequency comb in a chi-2 sheet micro optical parametric oscillator via cavity phase matching. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1812.06389 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge discussions with Jinkang Lim, Abhinav Kumar, Hao Liu, Wenting Wang, and Andrey Matsko. The authors acknowledge funding support from the Office of Naval Research (N00014-16-1-2094), the National Science Foundation (awards 1824568, 1810506, 1829071, and Emerging Frontiers in Research and Innovation ACQUIRE 1741707), Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (contract B622827), the Air Force Office of Scientific Research Young Investigator Award (FA9550-15-1-0081), and the University of California—National Laboratory Office of the President center grant (LFR-17-477237).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y. designed the devices, performed the measurements, and analyzed the data. Analysis and interpretation of experimental results was conducted by J.Y. and S.-W.H. Sample contribution is by M.Y. and D.-L.K. J.Y. and C.W.W wrote the manuscript, with revision contributions by S.-W.H. and Z.X. All authors discussed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Huang, SW., Xie, Z. et al. Coherent satellites in multispectral regenerative frequency microcombs. Commun Phys 3, 27 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0274-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0274-x

This article is cited by

-

Towards integrated photonic interposers for processing octave-spanning microresonator frequency combs

Light: Science & Applications (2021)

-

Spectral extension and synchronization of microcombs in a single microresonator

Nature Communications (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.