Abstract

Polaritons are hybrid light–matter quasiparticles arising from the strong coupling of excitons and photons. Owing to the spin degree-of-freedom, polaritons form spinor fluids able to propagate in the cavity plane over long distances with promising properties for spintronics applications. Here we demonstrate experimentally the full control of the polarization dynamics of a propagating exciton–polariton condensate in a planar microcavity by using a magnetic field applied in the Voigt geometry. We show the change of the spin-beat frequency, the suppression of the optical spin Hall effect, and the rotation of the polarization pattern by the magnetic field. The observed effects are theoretically reproduced by a phenomenological model based on microscopic consideration of exciton–photon coupling in a microcavity accounting for the magneto-induced mixing of exciton–polariton and dark, spin-forbidden exciton states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The remarkable progresses in the control of matter–light interaction in semiconductor optical microcavities have made it possible to design a new generation of optoelectronic devices1,2,3,4,5,6,7. These are based on the peculiar properties of exciton-polaritons, half-light half-matter bosonic quasiparticles arising from the strong coupling between photonic cavity modes and excitons in quantum wells placed inside the cavity. One of the most remarkable properties of polaritons is that they have a spin degree of freedom inherited from the photon chirality and exciton spin angular momentum that shows long coherence time and the possibility to be actively manipulated by external fields through the excitonic component8,9. This additional feature of polaritons significantly broadens the range of their possible applications to include what is known under the name of spinoptronics. By now, there are already several implemented concepts in the form of spinoptronics devices such as the “Datta and Das” spin transistor5,10, the polaritonic analog of a Berry-phase interferometer6, and the exciton–polariton spin switch7,11. In all these works, a central aspect is the ability to control the spin of polaritons using internal as well as external factors to affect their polarization properties.

From a fundamental point of view, the dominant effect on the polariton spin dynamics is the optical spin Hall effect (OSHE)12,13,14. Basically, it originates from the longitudinal-transverse (LT) splitting \({\Delta }_{{\rm{LT}}}\) of exciton–polariton states. The effect of this splitting can be described by an effective magnetic field oriented in the plane of the cavity, strongly dependent on the direction of the quasi-particle propagation and its velocity, giving rise to the polariton spin precession as it propagates in the cavity plane. One of the main problems, in particular when polarization is a key parameter in polariton devices, is the control of such an effective magnetic field, which in turn directly affects the polariton state. Usually, the Faraday geometry with the magnetic field directed along the cavity normal is used. In this configuration, the studies of the influence of the magnetic field on the polariton dispersion15, coherence properties16, as well as on the spin textures in excitonic17 and polaritonic18 systems have been reported. However, such geometry cannot be effective on the control of the OSHE19,20,21,22.

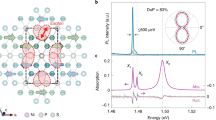

By contrast, the effect on exciton–polariton spin dynamics in the Voigt geometry, with the external magnetic field within the plane of the quantum well, has not been studied so far. This is because the in-plane field does not directly couple with the polariton pseudospin and one may expect its effect to be quite minor. In this study we demonstrate that this is not the case by showing that an in-plane magnetic field increases (decreases) the effect of the intrinsic LT splitting \({\Omega }_{{\rm{LT}}}\) when applied perpendicularly (parallel) to the propagation direction of polaritons (see Fig. 1a, b). The direct magnetic control of the polariton spin transport is shown both in a confined one-dimensional (1D) geometry and in the whole two-dimensional (2D) plane of the cavity through the application of an external magnetic field directed in the cavity plane. In this context, we show the possibility to control and even totally suppress the OSHE for polaritons propagating in a given direction by properly choosing the magnitude and the direction of the applied field. By imaging the polariton propagation in 2D space, it is possible to observe the stretching and the contraction of the circular pseudospin patterns depending on the relative orientation of polariton propagation and external magnetic field. All the experimentally observed phenomena can be described within a phenomenological analytical model developed from the microscopic model of the exciton–photon interaction in a planar microcavity taking into account both the magnetic-field-induced mixing of bright polariton doublet with dark excitonic states and nonlinear effects originating from the polariton–polariton interactions.

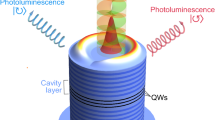

a, b Polaritons are injected with a finite velocity v (black arrow), which is either perpendicular (a) or parallel (b) to the external magnetic field B (green arrow). Polariton pseudospin (red arrow) is not directly coupled to the external in-plane magnetic field B, but it precesses around the effective magnetic field \({{\mathbf{\Omega }}}_{{\rm{LT}}}\) (blue arrow) induced by the intrinsic longitudinal-transverse splitting. Here we show that the external in-plane magnetic field B contributes positively to \({{\mathbf{\Omega }}}_{{\rm{LT}}}\) when \({\bf{B}}\perp {\bf{v}}\) (in a) and counteracts \({{\mathbf{\Omega }}}_{{\rm{LT}}}\) when \({\bf{B}}\parallel {\bf{v}}\) (in b). c Scheme of the optical setup used for the data shown in Figs. 2 and 3. The pump is a continuous wave laser (CW) tuned to energy and momentum resonance with the polariton dispersion at \(\lambda =773\ {\rm{nm}}\). The optical elements LP and L4 are linear polarizer and quarter waveplate, respectively, used to inject polaritons with a controlled circular polarization. The signal is directed by a beam splitter into the polarization optics and finally detected by a charge coupled device (CCD) placed after the spectrometer (SM). The circular polarization degree \({P}_{{\rm{c}}}\) is obtained by measuring co- and cross-polarized emission intensities (with respect to the pump) via rotation of L4 in the detection path.

Results

The sample studied in this work is a high finesse 3\(\lambda\)/2 GaAs/AlGaAs planar microcavity grown along \(z\parallel [001]\) axis with a state-of-the-art polariton lifetime of about 100 ps. The high quality factor \(Q\ > \ 1{0}^{5}\) and the low density of defects allow for ballistic propagation of polaritons to cover several hundreds of micrometers, as recently demonstrated by different groups23,24. The microcavity contains 12 GaAs quantum wells (7 nm wide) placed at three anti-node positions of the electric field, providing a vacuum Rabi splitting of 16 meV. The front (back) mirror consists of 34 (40) pairs of \({\rm{AlAs}}/{{\rm{Al}}}_{0.2}{{\rm{Ga}}}_{0.8}\)As layers and the cavity-exciton detuning is slightly negative, about −2 meV. Polaritons are injected both resonantly (for 1D propagation measurements) and nonresonantly (for 2D propagation measurements) using a low-noise, narrow-linewidth Ti:sapphire laser with stabilized output frequency in a continuous wave operation mode. The sample is kept at a temperature of around 10 K. The sample emission is collected, filtered in polarization, and sent to the entrance slit of a spectrometer coupled with a charge coupled device camera (see Fig. 1c).

In order to study the 1D case, we resonantly inject \({\sigma }^{+}\) circularly polarized polaritons with a finite momentum into natural misfit dislocations present along the \([1\bar{1}0]\) axis of the sample (see Supplementary Note 1)25,26. The 1D confinement is shallow but allows to observe polariton emission up to 400 μm from the laser injection point thanks to a negligible spread in the transversal direction. The coherent spin oscillations during the propagation of polaritons are measured by selectively detecting the emission intensity co- (\({\sigma }^{+}\)) and cross-polarized (\({\sigma }^{-}\)) with respect to the exciting laser. The circular polarization degree, \({P}_{{\rm{c}}}\), is then obtained as \({P}_{{\rm{c}}}=({I}_{{\sigma }^{+}}-{I}_{{\sigma }^{-}})/({I}_{{\sigma }^{+}}+{I}_{{\sigma }^{-}})\). In Fig. 2, polaritons are injected with a speed of 1.5 μs ps−1 and the magnetic field is applied in the plane of polariton propagation normally to the propagation direction (in Fig. 2a, b, \({P}_{{\rm{c}}}\) is shown for applied magnetic field of 0 T and 9 T, respectively). The pronounced oscillations of the circular polarization degree as a function of the spatial coordinate are observed being a signature of the polariton pseudospin precession in the course of propagation. The emission intensity along the propagation direction with the applied magnetic field of 9 T is shown in Fig. 2c, d for the co- and cross-polarized detections, respectively. Interestingly, and somewhat unexpectedly, the magnetic field affects the frequency of the spatial oscillations of \({P}_{{\rm{c}}}\), which increases quadratically the spatial frequency with the intensity of the magnetic field, as shown in Fig. 2e.

a, b Circular polarization degree vs. \(y\)-coordinate for \(B=0\) T (a) and \(B=9\) T (b). In all figures \(y=0\) corresponds to the distance of 50 μm from the excitation spot, smaller distances are removed to avoid contribution of the scattered light. Red curves show experimental data, blue lines are fits after Eq. (3). c, d False color plots of spatial distribution of intensities in \({\sigma }^{+}\) (co-polarized, c) and \({\sigma }^{-}\) (cross-polarized, d) at 9 T. The scale bar is 50 μm. e Propagation constant \(\kappa\) in Eq. (3) as a function of \(B\) (dots are experiment, solid curve is the fit after Eq. (4) with \(v\) = 1.52 μm ps−1, \(\hslash {\Delta }_{{\rm{LT}}}\) = 30 μeV, \(\hslash \beta\) = 0.1 μeV T−2.

The effect of the magnetic field applied in the same direction of the dislocation is measured with the sample rotated by \(9{0}^{\circ }\) with respect to Fig. 2. In Fig. 3, the suppression of the OSHE induced by the magnetic field applied parallel to polariton velocity is shown. To limit the intrinsic \({\Omega }_{{\rm{LT}}}\) to values comparable to those induced by moderate magnetic fields (B < 9 T), a smaller in-plane momentum \(k\) is used with respect to Fig. 1 (\({\Delta }_{{\rm{LT}}}\) increases quadratically with \(k\)). The smaller OSHE results in a slower spin precession, still visible at \(B\) = 0 T in the space window captured in the experiments (Fig. 3a). Increasing the magnetic field intensity, the modulation in space of the circular polarization degree initially decreases (Fig. 3a–c) and then increases with a constant positive offset in the co-polarized component (Fig. 3c–h).

a–f Circular polarization degree for the magnetic field oriented along the propagation direction \({\bf{B}}\parallel y\). The magnetic field magnitude is \(B\) = 0, 3, 5.5, 6.5, 7.5, 8.5 T from a–f, respectively. g, h False color plots of spatial distribution of intensities in \({\sigma }^{+}\) (co-polarized, g) and \({\sigma }^{-}\) (cross-polarized, h) at 9 T. The scale bar is 50 μm. In the a–f red dots are experiment, blue solid curves are solutions of the nonlinear Eq. (1) with the following parameters: \(v\) = 0.4 μm ps−1, \(\hslash {\Delta }_{{\rm{LT}}}\) = 2 μeV, \(\hslash \alpha {S}_{0}\) = 30 μeV, \({\gamma }_{{\rm{s}}}\ =\ 0.004\ {{\rm{ps}}}^{-1}\), \(\hslash \beta\) = 0.1 μeV T−2. The initial conditions are \({S}_{{z}_{0}}=0.9\), \({S}_{{y}_{0}}=-0.15\), \({S}_{{x}_{0}}=-{(1-{S}_{{y}_{0}}^{2}-{S}_{{z}_{0}}^{2})}^{1/2}\).

The observed effects can be quantitatively described within a pseudospin model parametrizing the polariton spin density matrix through the vector \({{\bf{S}}}_{{\bf{k}}}=({S}_{x},{S}_{y},{S}_{z})\), the \(z\) component of which describes the circular polarization degree of the particles and the in-plane components characterize the linear polarization degree in two sets of axes (Supplementary Notes 2 and 3). The equation of motion for the pseudospin of polaritons in the \({\bf{k}}\) state is written as12

Hereafter, we assume ballistic propagation of polaritons, use the set of axes with \(x\parallel [110]\), \(y\parallel [1\bar{1}0]\), and \(z\parallel [001]\), \({{\mathbf{\Omega }}}_{{\bf{k}}}\) is the effective pseudospin precession frequency, and the last term accounts for the spin relaxation processes with the rate \({\gamma }_{{\rm{s}}}\). The effective precession frequency components read

and contain contributions from the LT splitting of polariton modes \({\Delta }_{{\rm{LT}}}\) in the linear polarization components, the effect of the applied external magnetic field in the cavity plane \(\beta {B}_{x,y}^{2}\), and the so-called self-induced Larmor precession of the polariton pseudospin due to the polariton–polariton interactions (\(\alpha\)) treated here within the mean-field approach8,27,28,29. Importantly, the in-plane components of the effective field contain the quadratic magnetic field contributions. The form of these terms follows from the symmetry arguments, as the quadratic combinations \({B}_{i}{B}_{j}\) and \({k}_{i}{k}_{j}\) with \(i,j=x,y\) transform in the same way already in the isotropic approximation and the effects of \({C}_{2v}\) point symmetry of the studied structure on the magnetic-field-induced terms are disregarded. Microscopically, the parameter \(\beta\) results from magneto-induced mixing of polariton states and dark (spin-forbidden) excitons with the additional contribution from the diamagnetic effect, just like for excitons in quantum wells and quantum dots30,31 (see Supplementary Note 4 for the details).

Equation (1) can be solved analytically for various experimentally relevant configurations. Let us first set \(\alpha =0\), i.e., neglect the effect of the polariton–polariton interactions and assume that the polaritons propagate along the \(y\)-axis and \({\bf{B}}\) is either parallel or perpendicular to the polariton velocity. From Eqs. (2a)–(2c), it follows that \({\Omega }_{y}=0\) and

Here, the propagation constant of the oscillatory distribution of pseudospin is:

and the pseudospin decay length \({\ell }_{{\rm{s}}}=v/{\gamma }_{{\rm{s}}}\), where \({\bf{v}}={\bf{k}}/m\) (with \(m\) being the polariton effective mass) is the polariton velocity. For positive \(\beta\) and \({\bf{B}}\perp {\bf{k}}\), Eq. (4) predicts a monotonic increase of the propagation constant \(\kappa\) with the square of the magnetic field magnitude \({B}^{2}\), in full agreement with the experimental results shown in Fig. 2e. By contrast, with \({\bf{B}}\parallel {\bf{k}}\) the dependence \(\kappa (B)\) is more complicated: from Eq. (4), it follows that \(\kappa\) is a non-monotonic function of \(B\). First, it decreases for \(B\,<\, {B}_{{\rm{c}}}=\sqrt{{\Delta }_{{\rm{LT}}}/\beta }\) and then increases for higher field intensities. Under the condition \(B={B}_{{\rm{c}}}\), the complete stop of oscillations is expected due to the suppression of the LT splitting by the magnetic field similarly to the field-induced suppression of exciton anisotropic splitting in quantum dots30,31. Qualitatively, the estimations within the linear model are in agreement with the experimental data presented in Fig. 3, with \({B}_{{\rm{c}}}\approx\) 4 T.

Although Eqs. (3) and (4) quantitatively fit the data in Fig. 2 (see solid lines in the panels b, c), the linear model is not sufficient to describe all the peculiarities of the polariton polarization dynamics shown in Fig. 3. This is because the nonlinearity due to polariton–polariton interactions becomes of particular importance in the situation of \(B\approx {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\). Also, in the experimental geometry with \({\bf{B}}\parallel {\bf{k}}\), the polariton propagation velocity is relatively small, \(v\approx\) 0.4 μm ps−1, which results in the weaker manifestation of the LT-splitting effect. Indeed, one of the peculiarities seen in Fig. 3 is the positive offset in the \({S}_{z}(y)\) dependence. This effect is the manifestation of the presence of the third component of the effective magnetic field \({\Omega }_{{\bf{k}},z}\propto {S}_{z}\), which tilts the pseudospin precession axis towards the \(z\)-axis and suppresses partially the effect of the LT splitting18,32. The results of calculations for this configuration are shown by blue curves in Fig. 3 and closely match the experimental points. It is noteworthy that, as expected, the self-induced Zeeman splitting due to the polariton–polariton interactions decreases at lower densities and the dynamics of \({S}_{z}(y)\) returns to the harmonic character at the distance of about 300 μm.

To understand how the complete 2D polarization spatial distribution is affected by the application of an in-plane magnetic field, we performed a different experiment with a free, high velocity, radially expanding polariton condensate (Fig. 4). The experimental setup is similar to that shown in Fig. 1, but the laser frequency is now tuned far above the polariton resonance and a clean region of the sample is used to visualize the polariton condensate expanding in all directions from the pumping spot (see Supplementary Note 1). Even though obtained with a nonresonant circularly polarized pumping scheme, polariton condensates, in our case, inherit about \(40 \%\) of circular polarization from the pump13. With the aim of efficiently injecting polaritons, the energy of the pump is tuned at the first minimum of the reflection stop band, making it possible to reach the condensation density threshold in a region within the laser spot, blueshifted of about 4 meV from the bottom of the lower polariton branch. From this central region, a polariton flow is ballistically expelled and is free to radially propagate in the plane of the cavity outside the excitation spot region, with an acceleration due to the gradient in the potential resulting from the blueshift under the excitation spot33. This configuration enables polaritons to ballistically propagate with a speed of about 2 μm ps−1.

Measured circular polarization degree with \({\bf{B}}\parallel y\) (vertical direction) for magnetic field intensities of (0, 7, 9) T and the initial polarizations \({\sigma }^{+}\) (a–c) and \({\sigma }^{-}\) (d–f). The propagation velocity is about 1.8 μm ps−1. The horizontal dark rectangle in a–f is the shadow of the mask used to block the pump beam. The scale bar is 30 μm. g Cross-section of \({S}_{z}\) at 0 T (red line) and 9 T (blue line) along the dashed vertical line in a and c, respectively. The fitting function is \(A{e}^{-by}\sin (\kappa y+\phi )\). h Same as in g but for the opposite polarization \({\sigma }^{-}\), with \({S}_{z}\) along the dashed lines in d and f shown by red and blue lines, respectively. i Propagation constant \(\kappa\) along the vertical direction (dashed lines in a–f) as a function of the magnetic field extracted as best fit to the data for \({\sigma }^{+}\) (red) and \({\sigma }^{-}\) (blue) polarization. l–q The circular polarization degree in real space simulation based on Eqs. (5) and (6). The magnetic field intensities correspond to ones in a–f. Values of the parameters used for modeling are following: \(m=7\times 1{0}^{-5}{m}_{\mathrm{e}}\), where \({m}_{\mathrm{e}}\) is the free electron mass, \(\hslash {\Delta }_{{\rm{LT}}}{k}^{2}\) = 200 μeV μm−2, \(\hslash \beta\) = 0.65 μm T−2, \(\alpha ={\alpha }_{{\rm{R}}}/2\) = 1 μeV μm2, \(\gamma =0.17\ {{\rm{ps}}}^{-1}\), \({\gamma }_{{\rm{R}}}=1\ {{\rm{ps}}}^{-1}\), \(\hslash R\) = 0.05 meV μm2. The initial conditions are \({W}_{+(-)}(0)/{W}_{-(+)}(0)=17\) for the upper (l–n) (lower (o–q)) row panels.

Figure 4a–f shows the \({P}_{{\rm{c}}}\) for different magnetic field magnitudes. A small asymmetry in the distribution function already present at \(B=0\) T is initially compensated and then enhanced by the external magnetic field. Indeed, the pattern was at \(B=0\) T elliptical with the horizontal axis greater than the vertical but, by increasing the applied magnetic field, these axes become inverted and the ellipse gets rotated (see Fig. 4a–c). By changing the polarization degree of the exciting laser from right circular to left circular (Fig. 4d–f), we change the relative orientation of the polariton spin with respect to the magnetic field. In Fig. 4f, the long eccentricity axis at \(9\) T is oriented roughly perpendicularly to Fig. 4c, corresponding to a rotation of 90° between \({\sigma }^{+}\) and \({\sigma }^{-}\) as shown by the solid lines in (c) and (f), respectively. Correspondingly, the spatial frequency of the spin oscillations along the y-axis decreases with the magnetic field for \({\sigma }^{+}\) and is almost constant for \({\sigma }^{-}\), as shown in Fig. 4g–i.

Discussion

To model the 2D polarization distribution in real space, we turn to the generalized Gross–Pitaevskii equation for the two-component wave function \({\Psi }_{\sigma }(t,{\bf{r}})\) (\(\sigma =\pm 1\)):

coupled to the rate equations for the spin-resolved reservoir density of incoherent excitons \({n}_{{\rm{R}}}^{\sigma }(t,{\bf{r}})\):

In Eq. (5), \(\hat{{\bf{k}}}=(-{\rm{i}}{\partial }_{x},-{\rm{i}}{\partial }_{y})\) is the quasimomentum operator, \({V}_{{\rm{eff}}}^{\sigma }(t,{\bf{r}})=V({\mathbf{r}})+\alpha | {\Psi }_{\sigma }{| }^{2}+{\alpha }_{{\rm{R}}}{n}_{{\rm{R}}}^{\sigma }\) describes the blueshift of the polariton energy due to the intra-condensate polariton interactions and the interaction with the reservoir excitons, V(r) represents the static disorder potential typical in semiconductor microcavities, \({\alpha }_{{\rm{R}}}\) is the polariton–exciton interaction constant. The parameter \(R\) describes the stimulated scattering rate from the reservoir to the polariton state, \(\gamma\) and \({\gamma }_{{\rm{R}}}\) are the polariton and exciton (in the reservoir) relaxation rates, respectively. The exciton reservoir is excited by the nonresonant Gaussian optical pump \({W}_{\sigma }({\bf{r}})\).

Figure 4l–q illustrates the 2D expansion of \({P}_{{\rm{c}}}\) theoretically predicted from the model. The values of the external magnetic field magnitude \(B\) in this figure correspond to those in Fig. 4a–f. The resulting circular polarization degree during the polariton expansion in the 2D plane can also be qualitatively described by the same Eq. (1) applied to all \({\bf{k}}\) on the elastic circle of the radius \(k\), see Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 5. To distinguish the influence of different effects on the shape of the polarization pattern, it is possible to consider the following. At the pure circular initial polarization, in the presence of only the LT splitting, the circular polarization degree patterns in real space are rotationally invariant. A slight tilt and the squeezing of the patterns in \(x\) direction even in the absence of the external magnetic field are due to the fact that the initial polarization is not pure circular but it contains a small admixture of the linear components. In particular, the birefringence in the top Bragg mirror can be responsible for the appearance of the linear component in the polariton polarization34,35. This is taken into account in the model by introducing an appropriate imbalance in the reservoir pump power \({W}_{\sigma }({\bf{r}})\). Moreover, the external magnetic field tends to change the spatial frequency \(\kappa\) with, as shown above, a different effect depending on the relative direction of the external field and the propagation. According to Eq. (4), the absolute value of the propagation constant \(\kappa ({k}_{y},B)\) decreases with increasing \(B\) (directed along the y-axis) until the magnetic field compensates the effect of the LT splitting, while a further increase in \(B\) leads to the increase of the spatial frequency. In the propagation direction orthogonal to \(B\), the propagation constant \(\kappa ({k}_{x},B)\) monotonically increases with the increase of \(B\) on all extent.

In conclusion, we have experimentally demonstrated the control of the OSHE by tuning an external magnetic field applied in the direction of propagation of polaritons. This can be useful to avoid unwanted rotation of the polarization in polariton devices or by controlling the spin degree at a given position. In fact, if the spin precession is instead required13, the spin-beat frequency can be tuned by the external magnetic field applied perpendicularly to the propagation direction of polaritons. In the 2D expansion the in-plane magnetic field induces an additional polarization anisotropy in the structure that manifests itself as a deformation of the pseudospin patterns in real space. We have developed a theoretical model that qualitatively explains the observed effects.

Data availability

The raw experimental and numerical data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Imamoḡlu, A. & Ram, R. Quantum dynamics of exciton lasers. Phys. Lett. A 214, 193–198 (1996).

Gao, T. et al. Polariton condensate transistor switch. Phys. Rev. B 85, 235102 (2012).

Ballarini, D. et al. All-optical polariton transistor. Nat. Commun. 4, 1778 (2013).

Bajoni, D. et al. Optical bistability in a GaAs-based polariton diode. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 266402 (2008).

Johne, R., Shelykh, I. A., Solnyshkov, D. D. & Malpuech, G. Polaritonic analogue of Datta and Das spin transistor. Phys. Rev. B 81, 125327 (2010).

Shelykh, I. A., Pavlovic, G., Solnyshkov, D. D. & Malpuech, G. Proposal for a mesoscopic optical Berry-phase interferometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 046407 (2009).

Amo, A. et al. Exciton-polariton spin switches. Nat. Photonics 4, 361–366 (2010).

Shelykh, I. A., Kavokin, A. V. & Malpuech, G. Spin dynamics of exciton polaritons in microcavities. Phys. Stat. Solid. B 242, 2271–2289 (2005).

Mirek, R. et al. Angular dependence of giant Zeeman effect for semimagnetic cavity polaritons. Phys. Rev. B 95, 085429 (2017).

Espinosa-Ortega, T. & Liew, T. C. H. Complete architecture of integrated photonic circuits based on AND and NOT logic gates of exciton polaritons in semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. B 87, 195305 (2013).

Ballarini, D. et al. Transition from the strong- to the weak-coupling regime in semiconductor microcavities: Polarization dependence. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 201905 (2007).

Kavokin, A., Malpuech, G. & Glazov, M. Optical spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 136601 (2005).

Kammann, E. et al. Nonlinear optical spin Hall effect and long-range spin transport in polariton lasers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 036404 (2012).

Schmidt, D. et al. Dynamics of the optical spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 96, 075309 (2017).

Piȩtka, B. et al. Magnetic field tuning of exciton-polaritons in a semiconductor microcavity. Phys. Rev. B 91, 075309 (2015).

Chernenko, A. V. et al. Polariton condensate coherence in planar microcavities in a magnetic field. Semiconductors 50, 1609–1613 (2016).

High, A. A. et al. Spin currents in a coherent exciton gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 246403 (2013).

Morina, S., Liew, T. C. H. & Shelykh, I. A. Magnetic field control of the optical spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 88, 035311 (2013).

Rubo, Y. G., Kavokin, A. & Shelykh, I. Suppression of superfluidity of exciton-polaritons by magnetic field. Phys. Lett. A 358, 227–230 (2006).

Larionov, A. V. et al. Polarized nonequilibrium Bose-Einstein condensates of spinor exciton polaritons in a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 256401 (2010).

Walker, P. et al. Suppression of Zeeman splitting of the energy levels of exciton-polariton condensates in semiconductor microcavities in an external magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 257401 (2011).

Sedov, E. S. & Kavokin, A. V. Artificial gravity effect on spin-polarized exciton-polaritons. Sci. Rep. 7, 9797 (2017).

Caputo, D. et al. Topological order and equilibrium in a condensate of exciton-polaritons. Nat. Mater. 17, 145–151 (2018).

Steger, M. et al. Long-range ballistic motion and coherent flow of long-lifetime polaritons. Phys. Rev. B 88, 235314 (2013).

Gurioli, M. et al. Experimental study of disorder in a semiconductor microcavity. Phys. Rev. B 64, 165309–165315 (2001).

Zajac, J. M., Langbein, W., Hugues, M. & Hopkinson, M. Polariton states bound to defects in GaAs/AlAs planar microcavities. Phys. Rev. B 85, 165309 (2012).

Panzarini, G. et al. Exciton-light coupling in single and coupled semiconductor microcavities: polariton dispersion and polarization splitting. Phys. Rev. B 59, 5082–5089 (1999).

Cao, H. T., Doan, T. D., Thoai, D. B. T. & Haug, H. Polarization kinetics of semiconductor microcavities investigated with a Boltzman approach. Phys. Rev. B 77, 075320 (2008).

Glazov, M. M. & Kavokin, A. V. Spin waves in semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. B 91, 161307 (2015).

Stevenson, R. M. et al. Magnetic-field-induced reduction of the exciton polarization splitting in InAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 73, 033306 (2006).

Glazov, M. M., Ivchenko, E. L., Krebs, O., Kowalik, K. & Voisin, P. Diamagnetic contribution to the effect of in-plane magnetic field on a quantum-dot exciton fine structure. Phys. Rev. B 76, 193313 (2007).

Lafont, O. et al. Controlling the optical spin Hall effect with light. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 061108 (2017).

Ballarini, D. et al. Macroscopic two-dimensional polariton condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 215301 (2017).

Askitopoulos, A. et al. Nonresonant optical control of a spinor polariton condensate. Phys. Rev. B 93, 205307 (2016).

Lundt, N. et al. Optical valley Hall effect for highly valley-coherent exciton-polaritons in an atomically thin semiconductor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 770–775 (2019).

Acknowledgements

D.C., D.B. and D.S. acknowledge the ERC project POLAFLOW (grant number 308136) and the ERC project ElecOpteR (grant number 780757). D.C., D.B. and D.S. thank P. Cazzato for the technical support. E.S.S. and A.V.K. acknowledge support from Westlake University (Project Number 041020100118). E.S.S. acknowledges partial support from the Grant of the President of the Russian Federation for state support of young Russian scientists No. MK-2839.2019.2. A.V.K. acknowledges the St. Petersburg University for the research grant ID 40847559. M.M.G. was partially supported by SPSU and DFG Project 40.65.62.2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C., D.B. and D.S. conducted the experimental measurements. E.S.S., M.M.G. and A.V.K. performed the analytical and numerical modeling. All the authors contributed to the discussion of the results and the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Caputo, D., Sedov, E.S., Ballarini, D. et al. Magnetic control of polariton spin transport. Commun Phys 2, 165 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0261-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0261-2

This article is cited by

-

Magneto-optical induced supermode switching in quantum fluids of light

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Spontaneous symmetry breaking in persistent currents of spinor polaritons

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Long-distance coupling and energy transfer between exciton states in magnetically controlled microcavities

Communications Materials (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.