Abstract

Zero-energy Andreev levels in hybrid semiconductor-superconductor nanowires mimic all expected Majorana phenomenology, including \(2{e}^{2}/h\) conductance quantisation, even where band topology predicts trivial phases. This surprising fact has been used to challenge the interpretation of various transport experiments in terms of Majorana zero modes. Here we show that the Andreev versus Majorana controversy is clarified when framed in the language of non-Hermitian topology, the natural description for quantum systems open to the environment. This change of paradigm allows one to understand topological transitions and the emergence of zero modes in more general systems than can be described by band topology. This is achieved by studying exceptional point bifurcations in the complex spectrum of the system’s non-Hermitian Hamiltonian. Within this broader topological classification, Majoranas from both conventional band topology and a large subset of Andreev levels at zero energy are in fact topologically equivalent, which explains why they cannot be distinguished.

Similar content being viewed by others

A hybrid semiconductor-superconductor nanowire can be tuned into a topological superconductor phase with Majorana zero modes (MZMs)1 when an external Zeeman field \(B\) exceeds a critical value \({B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) and the system undergoes a topological transition2,3. Since the early measurements4 following this remarkable theoretical prediction, there has been great progress in the field and the latest experiments report extremely robust zero-bias anomalies (ZBAs) in the differential conductance (\(\mathrm{d}I/\mathrm{d}V\))5,6. Such behaviour is consistent with tunneling into a MZM that emerges after the system becomes topological7,8. Despite the agreement, the topological interpretation has recently been challenged since an alternative explanation in terms of Andreev bound states (ABSs) with near-zero energy in the topological trivial phase \(B\ll {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) reproduces all the expected phenomenology in transport9,10,11,12,13,14, including the \(2{e}^{2}/h\) conductance quantization reported in ref. 6. This nagging ABS-versus-MZM dichotomy thus remains a critical issue in the field of Majorana nanowires.

In a semi-infinite quasi-1D superconducting system, with a bulk described by the Bloch Hamiltonian \({H}_{0}({\bf{k}})\), a non-trivial band-topological invariant rigorously implies that a protected MZM should arise at the system’s boundary, by virtue of the bulk-boundary correspondence. Physical systems, however, differ from this idealised picture. Deviations include finite length, non-uniform chemical potentials, or coupling to an external environment through leads and gates. In such systems the conventional band-topological picture cannot be invoked and the problem of discerning between ABS zero modes and MZMs is actually ill-defined, as the wavefunctions of both states are continuously connected, and topological transitions are in fact mere crossovers. As a result, the protection and Majorana character of near zero modes in finite systems is no longer an all-or-nothing proposition, but a matter of degree, ultimately connected to the degree of wavefunction non-locality of the zero mode in question15,16,17,18. Thus, an alternative language becomes necessary to establish whether ABSs that remain pinned to zero energy regardless of perturbations are fundamentally different or not from MZMs of conventional bulk topology. Here we show that non-Hermitian topology provides such a language, and makes it possible to define an alternative, general and precise topological classification criterion to distinguish trivial from non-trivial zero modes. Crucially, this classification matches band topological theory in the case of sufficiently long and uniform systems where the latter is applicable, while generalising it to a wider range of physically relevant scenarios where it is not.

Results

Non-Hermitian topology in superconductors

The key idea of non-Hermitian topology is to consider the system coupled to its environment, the relevant setup in open quantum systems (such as in nanowire transport experiments). Instead of considering the topological structure of the bands of an isolated bulk system described by a Hamiltonian \({H}_{0}\), one should study a different object: the distribution in the complex plane of the poles \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{p}}}\) of the open system’s retarded Green’s function (or, equivalently, of the scattering matrix),

Here \({H}_{{\rm{eff}}}(\omega )={H}_{0}+\Sigma (\omega )\) is an effective non-Hermitian Hamiltonian which takes into account both the system and its coupling to the reservoir (through the retarded self-energy \(\Sigma (\omega )\)). This seemingly simple extension often gives rise to richer topological structure in a vast variety of physical systems19,20,21,22 than in their Hermitian counterparts. The poles of the retarded Green’s function can be viewed as the complex eigenvalues of \({H}_{{\rm{eff}}}\), and have a well defined physical interpretation that generalizes the spectrum of the isolated system (namely, real eigenvalues of \({H}_{0}\)). They define quasi-bound states in the open system, with complex energies \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{p}}}=E-i\Gamma\), that decay into the reservoir with rate \(\Gamma \ge 0\), see Fig. 1. As discussed first by Pikulin and Nazarov in the context of nanowires coupled to superconductors23,24, the distribution of complex eigenvalues of \({H}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) allows for a natural topological classification of open system phases. This generalises that of band topology, defined solely in terms of \({H}_{0}\).

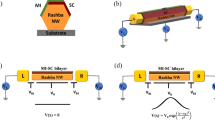

Exceptional points. a Sketch of a generic normal-superconductor (NS) junction formed when a proximitized nanowire with inhomogeneous chemical potential and pairing, \(\mu (x)\) and \(\Delta (x)\), is coupled to a reservoir at \(x=0\). Such junction is a natural host for Majorana zero modes. These can emerge even below the critical Zeeman field \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) as a result of an exceptional point (EP) bifurcation in the complex non-Hermitian spectrum, that in turn develops when the two Majorana components of a Bogoliubov mode (i.e. an Andreev level originally located at \(\pm E\) for \(B\) = 0) couple to the reservoir asymmetrically (\({\Gamma }_{0}^{{\rm{L}}}\ > \ {\Gamma }_{0}^{{\rm{R}}}\)) due to their spatial non-locality. Purple/light blue wave functions correspond to the spatially-separated, left (L) and right(R) Majorana components of the Bogoliubov mode, respectively. b Representation of the eigenvalues of the non-Hermitian Hamiltonian of the open system in the complex plane. The eigenvalues evolve as a function of some external parameter \(B\) until they coalesce at a so-called EP and then bifurcate into two purely imaginary eigenvalues with different decay rates to the reservoir, \({\Gamma }_{\pm }\) (quasi-bound Majorana zero modes). Inset shows the evolution of real and imaginary eigenenergies across the EP

In superconductors, the change to an open setting with a non-Hermitian \({H}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) has deep implications. When coupled to a reservoir, a parity crossing (point in parameter space where a Bogoliubov-de Gennes (BdG) excitation crosses zero energy) of the isolated system may or may not become stabilised, transforming into a robust zero mode insensitive to perturbations. Stabilisation of this kind provides the precise criterion for topologically non-trivial zero modes. The correct language to understand the zero energy stabilisation mechanism is that of bifurcations of the complex eigenvalues. These are a direct consequence of the underlying charge-conjugation (electron-hole) symmetry of the BdG formalism, which dictates that if \(\epsilon\) is an eigenvalue, so is \(-{\epsilon }^{* }\). In an open superconducting system, this condition can be satisfied in two non-equivalent ways, see Fig. 1b. One can have pairs of eigenvalues located symmetrically at opposite sides of the imaginary axis (blue dots) or, alternatively, have independent self-conjugate eigenvalues lying exactly on the imaginary axis (red dots). The former correspond to standard finite-energy ABSs (BdG excitations symmetrically located at \(\pm E\) and with equal decay rate \(\Gamma\) to the reservoir). The latter correspond to non-trivial zero modes in the context of open systems. A bifurcation of two trivial ABSs (\({\epsilon }_{\!\pm }=-{\epsilon }_{\mp }^{* }=\pm E-i\Gamma\)) into two non-trivial zero modes with different decay rates (\({\epsilon }_{\!\pm }=-{\epsilon }_{\pm }^{* }=-i{\Gamma }_{\!\pm }\)) defines an exceptional point (EP). More generally, EPs are points in parameter space where a non-Hermitian \({H}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) becomes non-diagonalizable through the coalescence of both eigenvalues and eigenvectors25,26. They have been extensively discussed in the context of open photonic systems27,28,29 and, more recently, in other physical contexts such as Dirac and Weyl materials30,31,32,33.

Minimal model of an EP bifurcation

Let us illustrate the mathematical structure of an EP bifurcation by considering the low energy Hamiltonian of a single parity crossing, \({H}_{0}={E}_{0}{\tau }_{{\rm{z}}}\), with \({\tau }_{{\rm{z}}}\) the Pauli matrix in particle-hole space. Since, mathematically, one can always decompose a local ABS quasiparticle excitation in terms of two Majorana operators, denoted left (L) and right (R) (see Supplementary Note 1), it is enlightening to write \({H}_{0}\) in the Majorana basis and take into account the possibility, allowed by charge-conjugation symmetry, that each of these Majoranas is coupled differently to the reservoir, with couplings \({\Gamma }_{0}^{{\rm{L}}}\ \ne \ {\Gamma }_{0}^{{\rm{R}}}\). The Hamiltonian in the Majorana basis reads:

Its eigenvalues are \({\epsilon }_{\!\pm }=-i{\Gamma }_{0}\pm \sqrt{{E}_{0}^{2}-{\gamma }_{0}^{2}}={E}_{\!\pm }-i{\Gamma }_{\!\pm }\), in terms of the average coupling \({\Gamma }_{0}\equiv ({\Gamma }_{0}^{{\rm{L}}}+{\Gamma }_{0}^{{\rm{R}}})/2\) and its asymmetry \({\gamma }_{0}\equiv ({\Gamma }_{0}^{{\rm{L}}}-{\Gamma }_{0}^{{\rm{R}}})/2\). The square root term produces two different regimes. For \(| {E}_{0}| \ > \ {\gamma }_{0}\) we obtain the standard ABS solution with opposite real energies \({E}_{\pm }=\pm \!\sqrt{{E}_{0}^{2}-{\gamma }_{0}^{2}}\) and equal decays \({\Gamma }_{\pm }={\Gamma }_{0}\). In contrast, when \(| {E}_{0}| \ < \ {\gamma }_{0}\) we get two purely imaginary eigenvalues, \({E}_{\pm }=0\), with different decay to the reservoir, \({\Gamma }_{\pm }={\Gamma }_{0}\!\pm \!\sqrt{{\gamma }_{0}^{2}-{E}_{0}^{2}}\). The two regimes are separated by the EP bifurcation where the square root vanishes. Thus, the mathematically precise non-Hermitian criterion of non-triviality is the development of an EP bifurcation, which happens whenever the coupling asymmetry is larger than the energy of the lowest ABS, \({\gamma }_{0}\ > \ | {E}_{0}|\). We can thus define the dimensionless parameter \(\nu \equiv ({\gamma }_{0}-| {E}_{0}| )/{\Gamma }_{0}\), whose sign \(-1\) and \(+1\) represents trivial and non-trivial topology. The two phases are simultaneously characterised by zero and non-zero normalised decay asymmetry \(\gamma /\Gamma =({\Gamma }_{+}-{\Gamma }_{-})/({\Gamma }_{+}+{\Gamma }_{-})\), respectively. This quantity can also be understood as a degree of Majorana decoupling, since a maximum \(\gamma /\Gamma \to 1\) implies that one of the Majorana poles has become non-decaying (\({\Gamma }_{-}\to 0\)) and is completely decoupled from the reservoir.

EPs in microscopic nanowire models

We now turn to the emergence of EPs in generic Majorana nanowires of arbitrary length, pairing and density profiles. The connection between the corresponding microscopic nanowire model \({H}_{0}\) (see “Methods”) and the low-energy effective model in Eq. (2) can be established in terms of particle/hole Bogoliubov wavefunctions \({u}_{\sigma }(x),{v}_{\sigma }(x)\), of the lowest-lying microscopic eigenstates. Such states corresponds to operators \({c}_{0}\) and \({c}_{0}^{\dagger }\), where

The Majorana components of these states are

where the Majorana wavefunctions are given by \({u}_{\sigma }^{{\rm{L}}}(x)=[{u}_{\sigma }(x)+{v}_{\sigma }^{* }(x)]/\sqrt{2}\) and \({u}_{\sigma }^{{\rm{R}}}(x)=-i[{u}_{\sigma }(x)-{v}_{\sigma }^{* }(x)]/\sqrt{2}\). In terms of the spinors \({{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{{\rm{L}},{\rm{R}}}(x)=\left({u}_{\uparrow }^{{\rm{L}},{\rm{R}}},{u}_{\downarrow }^{{\rm{L}},{\rm{R}}}\right)\), the effective model parameters are given by the relation

Equation (5) shows that a finite coupling asymmetry \({\gamma }_{0}/{\Gamma }_{0}\) arises as a result of a spatial separation of Majorana wavefunctions, as it implies \(| {{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{{\rm{L}}}(0){| }^{2}\ne | {{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{{\rm{R}}}(0){| }^{2}\) (for further discussion, see Supplementary Note 4).

In the case of a sufficiently long and uniform proximitised Rashba nanowire2,3 the non-Hermitian topological criterion \({\gamma }_{0}\ > \ | {E}_{0}|\) in terms of EPs perfectly matches the band topological criterion \(B\ > \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\). This is shown in Fig. 2a, b, where we compare the evolution of eigenvalues in isolated and open, long nanowires. We see that robust MZMs emerge at an EP in the latter case (blue circle), exactly at the gap inversion point \(B={B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) predicted by band topology. In the case of shorter nanowires, however, a comparison between the isolated and open cases, Fig. 2c–j, reveals that the band topological \(B\ > \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) criterion fails to predict correctly the appearance of MZMs, since their finite overlap along the nanowire length hybridises them away from zero energy, yielding oscillatory ABSs separated by parity crossings. The \({\gamma }_{0}\ > \ | {E}_{0}|\) criterion (i.e. \(\nu \ > \ 0\)), in contrast, divides the \(B\ > \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) interval into trivial (split Majoranas, \(\nu \ < \ 0,\gamma /\Gamma =0\)) and non-trivial (pinned zero modes, \(\nu \ > \ 0,\gamma /\Gamma \ > \ 0\)) regions, separated by recurring EPs, see Fig. 2k–o. The extension of non-trivial \(B\) intervals around each isolated-system parity crossing is linked to the degree of Majorana wavefunction non-locality, which makes this a physically sound criterion. This extends to the case of extremely short nanowires, Fig. 2g–j, where the large Majorana overlap reduces the non-trivial phases to \(B\) intervals of measure zero.

Emergence of non-Hermitian topology for finite length uniform wires. Various quantities versus Zeeman field \(B/{B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) are displayed for five (uniform potential) nanowires with decreasing lengths \({L}_{{\rm{S}}}\): a–j shows spectra for isolated (decoupled from the reservoir) nanowires (first row) and for open (coupled to the reservoir) nanowires (second row). k–o shows the non-Hermitian topology criterion, while p–t shows the decay asymmetry. Length dependence: u energy splitting of overlapping Majoranas as a function of length \({L}_{{\rm{S}}}\) in an isolated wire. v decay asymmetry \(\gamma /\Gamma\) as a function of length \({L}_{{\rm{S}}}\) for the open wire. The exponential crossover behaviour of the energy splitting (blue dashed fit in (u)) is captured by the exponential saturation of \(\gamma /\Gamma \to 1\) within the non-Hermitian framework (red dashed fit in (v))

An important phenomenon usually takes place after crossing an EP, whereby one of the MZMs becomes decoupled from the reservoir (\({\Gamma }_{-}\to 0\), \(\gamma /\Gamma \to 1\)). By direct inspection of the solution to Eq. (2), we see that the maximum value of the decay asymmetry \(\gamma /\Gamma\) occurs at \({E}_{0}=0\) after the bifurcation and is actually given by the coupling asymmetry \({\gamma }_{0}/{\Gamma }_{0}\) itself which is in turn equal to the local maxima of the \(\nu =({\gamma }_{0}-| {E}_{0}| )/{\Gamma }_{0}\) parameter. This decoupling \(\gamma /\Gamma\), shown in Figs. 2p–t, is of crucial importance, as it dictates a constraint on the timescales for key non-trivial properties like non-Abelian braiding or the \(4\pi\)-periodic Josephson effect, and therefore controls the development of physically observable topological properties. Unlike the abrupt EP, this decoupling process is a crossover, which exponentially saturates to its maximum value \(\gamma /\Gamma \to 1\) for wire lengths of the order of the coherence length \(\xi\) (dashed line in Fig. 2v). This exponential crossover behaviour obtained with the non-Hermitian topology of the open wire is consistent with the expected exponential decay of the energy versus length of the corresponding isolated wire (Fig. 2u). A similar agreement between bulk topology and non-Hermitian topology can be found for the Kitaev model (Supplementary Note 2).

Having shown that non-Hermitian topology matches and extends previous results obtained with bulk topology methods in uniform nanowires, we now depart from the standard case and discuss situations with inhomogeneous potentials \(\mu (x)\) and \(\Delta (x)\). We consider two archetypical instances of ABS zero modes in open systems: a quantum dot parity crossing34 and a smoothly confined \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) zero-energy ABS9,10,11,12,13,14. While both are trivial according to band topology, we will show that the latter is non-trivial within non-Hermitian topology.

The quantum dot case is implemented by a normal region \(\Delta (x)=0\) that is much shorter than the coherence length \(\xi\) and is weakly connected to the nanowire through a \(\mu (x)\) barrier (Fig. 3a, top inset). It hosts a quantum dot-like state with spatially local Majorana components, \(| {{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{{\rm{L}}}(0){| }^{2} \sim | {{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{{\rm{R}}}(0){| }^{2}\) (Fig. 3a), and hence a symmetric coupling to the reservoir \({\gamma }_{0}/{\Gamma }_{0}\approx 0\). For the smoothly confined case, the normal region is comparable or larger than \(\xi\), and is connected to the nanowire by smoothly varying \(\mu (x)\) and \(\Delta (x)\) (Fig. 3b, top inset). It hosts ABSs with substantially non-local Majorana components, \(| {{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{{\rm{L}}}(0){| }^{2}\ \ne \ | {{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{{\rm{R}}}(0){| }^{2}\) (Fig. 3b) (further plots are shown in the Supplementary Note 4). The real and imaginary parts of the lowest-lying levels for both systems are shown in Fig. 3c (dot) and Fig. 3d (smooth junction) as solid and dashed red lines, respectively. The fully local quantum dot state, with zero coupling asymmetry \({\gamma }_{0}/{\Gamma }_{0}=0\), is not stabilised for \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\), and remains as a point-like parity crossing in the real spectrum, with a single finite lifetime. It is therefore a trivial ABS. Conversely, and just like in the preceding case of uniform wires, the smooth junction in Fig. 3d shows a bifurcation of its two Majorana decay rates \({\Gamma }_{\pm }\), and becomes stabilised at zero real energy for \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\). The corresponding non-Hermitian topological criterion \(\nu\) is shown in Fig. 3e and f. Clearly, the EP bifurcations occur at points where the non-Hermitian topological parameter \(\nu\) changes sign. Therefore, both the \(B\ > \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) uniform wire case and the \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) smooth junction case correspond to the same non-trivial class within this non-Hermitian topology classification, associated to the same spectral structure: an EP bifurcation due to wave function asymmetry at the contact (irrespective of the different microscopic mechanisms leading to such asymmetry). Mathematically, this is reflected in sharp jumps at the EP in both the topological parameter \(\nu\) and the decay asymmetry \(\gamma /\Gamma\) (see panels g and h), in strong contrast with the coupling asymmetry \({\gamma }_{0}/{\Gamma }_{0}\) which grows smoothly as a function of magnetic field (Supplementary Note 5).

Trivial and non-trivial zero modes in inhomogeneous nanowires. The microscopic property that governs the absence (presence) of an exceptional point (EP) bifurcation for \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) is wave function locality (non-locality), such as in a quantum dot state (local case, a); and with smoothly confined Andreev bound states (ABS) for \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) (non-local case, b). The corresponding profiles \(\mu (x)\) and \(\Delta (x)\) are shown in the top inset panels. Panels (c–d) show the complex spectrum versus Zeeman field for (c) the quantum dot state (trivial parity crossing); and (d) the smoothly confined ABS for \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\). The decay rates (imaginary energy) of the two lowest states are shown in dashed red. Exceptional points (circles) appear as decay rate bifurcations accompanied by real energies (solid red) stabilised at zero. The trivial parity crossing in (c) does not show an EP bifurcation for \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) since the non-Hermitian topological criterion \(\nu \equiv ({\gamma }_{0}-| {E}_{0}| )/{\Gamma }_{0}\ > \ 0\) is not fulfilled at low Zeeman fields (e). The EP bifurcation occurs far from this trivial parity crossing (near \(B={B}_{{\rm{c}}}\), as expected for a long uniform wire). On the contrary, a smooth inhomogeneity gives rise to stable zero modes after an EP at \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) (d), with non-Hermitian topological criterion \(\nu \ > \ 0\) (f). The decay asymmetry \(\gamma /\Gamma\) changes accordingly with sharp increases from \(\gamma /\Gamma =0\) to \(\gamma /\Gamma \to 1\) at \(B={B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) (g) and \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) (h). Detailed parameters can be found in the Supplementary Table 1

Wave functions of eigenstates

We next discuss the properties of the wave functions of the two bifurcating Bogoliubov eigenstates \({\psi }_{\pm }(x)=({u}_{\uparrow \pm }(x),{u}_{\downarrow \pm }(x),{v}_{\uparrow \pm }(x),{v}_{\downarrow \pm }(x))\), for both uniform and inhomogeneous wire cases (Fig. 4). As before, each of these low-energy Bogoliubov modes can be decomposed into Majorana components Eq. (4). Importantly, these Majorana components are not eigenstates of the problem before the EP bifurcation but they do become (decaying) eigenstates at and after the EP, where their real energy remains pinned to zero (for further discussion, see Supplementary Note 1).

Wave function evolution across an exceptional point (EP). The bifurcating eigenstates of the non-Hermitian nanowire Hamiltonian are not orthogonal close to the exceptional point. a Shows the inner product modulus \(| {\psi }_{+}^{* }\cdot {\psi }_{-}|\) of the two lowest eigenstates \({\psi }_{\pm }\) as they cross the EP. The two eigenstates are found to coalesce at the EP (inner product of modulus 1). The eigenstate wave functions density along the nanowire is shown in b before the EP, c at the EP and d after the EP, at values of \(B/{B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) marked by vertical solid lines in (a). We see that wave functions also bifurcate into non-local (decaying) Majorana eigenstates after the EP. Left and right columns correspond to a uniform and a smoothly confined nanowire, respectively

The eigenvalue bifurcation at the EP comes hand in hand with a coalescence of the corresponding eigenstates. State coalescence is captured by the modulus of the inner product \(| {\psi }_{+}^{* }\cdot {\psi }_{-}| \equiv | {\int }_{0}^{L}dx\ {\psi }_{+}^{* }(x)\cdot {\psi }_{-}(x)|\) (Fig. 4a). At low magnetic fields, before the EP, the wave functions \({\psi }_{+}(x)\) and \({\psi }_{-}(x)\) are orthogonal as expected, \(| {\psi }_{+}^{* }\cdot {\psi }_{-}| \approx 0\). Right at the EP, \({\psi }_{+}(x)\) and \({\psi }_{-}(x)\) become exactly parallel, which results in a maximum \(| {\psi }_{+}^{* }\cdot {\psi }_{-}| =1\). After the EP, the eigenstates are once more orthogonal but their physical character is completely different since they now have pure Majorana character, \({\psi }_{\pm }(x)=({u}_{\uparrow }^{{\rm{L}}/{\rm{R}}}(x),{{u}_{\uparrow }^{{\rm{L}}/{\rm{R}}}}^{* }(x),{u}_{\downarrow }^{{\rm{L}}/{\rm{R}}}(x),{{u}_{\downarrow }^{{\rm{L}}/{\rm{R}}}}^{* }(x))\), with asymmetric decay into the reservoir due to their non-locality. This is demonstrated in Fig. 4, where we show the eigenstates for increasing magnetic fields before (b), at (c) and after (d) the EP.

The coalescence phenomenon at an EP is universal, a rather non-trivial fact given the very different properties of the microscopic systems considered here. Such coalescence implies that eigenstates no longer span the whole system’s Hilbert space. This defective aspect of the Hamiltonian at EP bifurcations25,26 cannot arise in a Hermitian context, and leads to very unusual time evolution of states (e.g. polynomial terms of linear or higher order in time instead of pure exponentials at the EP35,36). An interesting future step toward clarifying the intriguing connections between EPs and Majorana zero modes in superconductors would be to explore the observable consequences of anomalous dynamics at the EP.

Physical consequences of EPs in transport observables

We now show how EPs and the subsequent Majorana decoupling are directly observable in transport by analysing the differential conductance \(dI/dV\), computed using the Blonder-Tinkham-Klapwijk formalism (“Methods”). The typical tunnel widths in all calculations are always in the limit \(\Gamma \ \gtrsim \ {k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\)37. In Fig. 5 we present the typical behaviour of the \({{d}}I/{d}V\) for the dot coupled to a long nanowire (a), the smooth case (b), and the uniform nanowire case (c). In the top inset panels we see that, as soon as the system crosses an EP and the decay asymmetry jumps to a non-trivial \(\gamma /\Gamma \sim 1\) (thick grey lines), the low-temperature linear conductance \({d}I/{d}V{| }_{V\to 0}\) becomes nearly quantised to \(2{e}^{2}/h\) (results for \(T=20\) mK and \(T=50\) mK are shown as blue and red dashed lines, respectively). A full analysis of \(dI/dV {|}_{V \to 0}\) and \(\gamma /\Gamma\) versus Zeeman field and junction smoothness is presented in Supplementary Note 6. At zero temperature and constant \(B\) (white dashed cuts in the density plots), these \(2{e}^{2}/h\) transport anomalies show, as a function of bias \(V\), a characteristic split-Lorentzian profile [right panels in Fig. 5b, c], indistinguishable in the smooth and uniform cases. This structure is a measurable signature of the bifurcated poles, and hence of non-trivial topology, with the widths of the broader peak and central dip corresponding to \({\Gamma }_{+}\) and \({\Gamma }_{-}\), respectively. Complete Majorana decoupling \(\gamma /\Gamma =1\) removes the dip, and perfect \(2{e}^{2}/h\) conductance quantization is reached at zero bias and temperature. This result for the conductance is well-known13,14,38 but the remarkable connection with the EP physics discussed here has thus far been overlooked. This connection naturally explains why zero modes at \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) systematically result in \(2{e}^{2}/h\)-quantised ZBAs expected at \(B\ > \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\), as soon as temperature exceeds \({\Gamma }_{-}\). After the pole decoupling \({\Gamma }_{-}\to 0\) there is no way to distinguish between a smoothly confined \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) zero-enery ABS, a finite-length \(B\ > \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) MZM, or a MZM in a strictly semi-infinite \(B\ > \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) nanowire. They all exhibit a low temperature differential conductance of \(2{e}^{2}/h\), independently of any fine tuning. In particular, it cannot exceed \(2{e}^{2}/h\), in contrast to the \(4{e}^{2}/h\) of standard ABSs in the limit of perfect Andreev reflection.

Differential conductance across an exceptional point (EP). \(dI/dV\) as a function of bias \(V\) and Zeeman field \(B/{B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) for the three systems discussed in this paper: long wire with a quantum dot state (a–c), nanowire with a smoothly confined Andreev bound states (d–f) and a nanowire with uniform density and pairing (g–i). a, d and g shows the \({{d}}I/{d}V\) at \(V=0\) at low temperatures (\(T=20\) mK and \(T=50\) mK, blue and red dashed lines, respectively). These jump towards a quantised \(2{e}^{2}/h\) value just as the Majorana asymmetry (thick grey line) becomes finite \(\gamma /\Gamma \sim 1\) upon crossing an EP (non-trivial topology). c, f and i shows the ZBAs at fixed \(B/{B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) (see white dashed cuts in the density plots). Only the latter two (non-trivial \(\gamma /\Gamma \ > \ 0\)) reach \(2{e}^{2}/h\) at \(T\to 0\)

Discussion

Our results show that by adopting the language of non-Hermitian topology of open systems, the topological nature of zero energy states in arbitrary superconducting nanowires is clarified. Specifically, this framework provides a theoretical explanation of why Majoranas from conventional band topology and so-called trivial zero-energy Andreev levels9,10,11,12,13,14 behave the same (they are topologically equivalent from the viewpoint of EP bifurcations). While a finite Majorana non-locality is the universal and experimentally relevant mechanism to achieve EP-mediated topological protection of zero modes in an open setting, it is important to stress that reservoir engineering could also be used to stabilise zero modes that are originally local in the closed system. This has been explicitly demonstrated for trivial zero-energy parity crossings39 that become stable zero modes through EP bifurcations when coupled to a spin-polarised reservoir40. In this case, the EP stabilises a couple of quasibound states at the contact with different decay rates (one per spin sector). Also, a spin-dependent coupling to the reservoir across, e.g., a spin-polarised barrier can further contribute to the decoupling of the Majoranas14. Unlike EPs arising from spatial non-locality, however, such spin-selective schemes do not guarantee that the stabilised zero modes enjoy generic protection against decoherence. More generally, we expect our results to be relevant in all situations where the coupling to an external reservoir stabilizes zero modes through EP bifurcations. Experimentally, we expect smoothly confined ABSs to be a very relevant case of common occurrence in clean samples, which explains the ubiquity of robust zero bias anomalies for \(B\ < \ {B}_{{\rm{c}}}\).

Methods

Model

We model the proximitised Rashba nanowire with a Hamiltonian of the form2,3

with Pauli matrices \(\overrightarrow{\tau }\) and \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }\) acting on the particle/hole and spin sectors, respectively. \(B=\frac{1}{2}g{\mu }_{{\rm{B}}}| \overrightarrow{{\mathcal{B}}}|\) is the Zeeman field with \(g\), \({\mu }_{{\rm{B}}}\) and \(\overrightarrow{{\mathcal{B}}}\), the gyromagnetic factor, the Bohr magneton, and the magnetic field aligned along the wire, respectively. \(\alpha\) is the spin-orbit coupling and \({m}^{* }\) the effective mass (we use typical values for InSb nanowires, see Supplemental Table 1). \(\mu\) and \(\Delta\) are the (possibly position-dependent) nanowire chemical potential and induced superconducting pairing, respectively. The bulk topological transition occurs at the critical Zeeman field \({B}_{{\rm{c}}}\equiv \sqrt{{\mu }^{2}+{\Delta }^{2}}\). In the smooth confinement case, we include a spatially-dependent potential \(\mu (x)\) and pairing \(\Delta (x)\) that smoothly interpolate between a superconducting nanowire bulk and a normal region on the left end, see Fig. 1b and Supplemental Note 3. The spectrum of \({H}_{0}\) of this isolated wire model is readily obtained by discretising it into a tight-binding lattice, that we then numerically diagonalise41 to solve \({H}_{0}(x){\psi }_{n}(x)={E}_{n}{\psi }_{n}(x)\), with \({\psi }_{n}(x)={[{u}_{n\uparrow }(x),{u}_{n\downarrow }(x),{v}_{n\uparrow }(x),{v}_{n\downarrow }(x)]}^{T}\). The diagonalised problem reads \({H}_{0}=\frac{1}{2}{\sum }_{n}{E}_{n}{c}_{n}^{\dagger }{c}_{n}\), with BdG quasiparticle operators defined as \({c}_{n}=\int {dx}\,{\psi }_{n}(x)\hat{\Psi }(x)\), where \(\hat{\Psi }(x)={[{\Psi }_{\uparrow }(x),{\Psi }_{\downarrow }(x),{\Psi }_{\uparrow }^{\dagger }(x),{\Psi }_{\downarrow }^{\dagger }(x)]}^{T}\) is a Nambu spinor written in terms of the original electron/hole excitations. For the physics discussed in this paper, we focus on the lowest excitation \({c}_{0}=\int {dx}\,{\psi }_{0}(x)\hat{\Psi }(x)=\int {{dx}}\,[{u}_{0\uparrow }(x){\Psi }_{\uparrow }(x)+{u}_{0\downarrow }(x){\Psi }_{\downarrow }(x)+{v}_{0\uparrow }(x){\Psi }_{\uparrow }^{\dagger }(x)+{v}_{0\downarrow }(x){\Psi }_{\downarrow }^{\dagger }(x)]\). This lowest energy BdG mode can be written in terms of two left/right self-conjugate Majorana operators

which read \({\gamma }_{{\rm{L}},{\rm{R}}}=\int {dx}{\sum }_{\sigma }{u}_{\sigma }^{{\rm{L}},{\rm{R}}}(x){\Psi }_{\sigma }(x)+{\left[{u}_{\sigma }^{{\rm{L}},{\rm{R}}}(x)\right]}^{* }{\Psi }_{\sigma }^{\dagger }(x)\). The Majorana components discussed in the main text are equal superpositions of electron-hole amplitudes of the form \({u}_{\sigma }^{{\rm{L}}}(x)=[{u}_{\sigma }(x)+{v}_{\sigma }^{* }(x)]/\sqrt{2}\) and \({u}_{\sigma }^{{\rm{R}}}(x)=-i[{u}_{\sigma }(x)-{v}_{\sigma }^{* }(x)]/\sqrt{2}\), and define two spinors \({{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{{\rm{L}},{\rm{R}}}(x)=({u}_{\uparrow }^{{\rm{L}},{\rm{R}}}(x),{u}_{\downarrow }^{{\rm{L}},{\rm{R}}}(x))\) (see Supplementary Note 1). Note that while the above decomposition of a BdG mode into Majorana components is general, only when this mode is located at zero energy the Majoranas are eigenstates of the problem themselves.

The coupling to a metallic reservoir is implemented by a spin-independent self-energy \(\Sigma (\omega )=i{\Gamma }_{x=0}\) added to the first lattice site17, and proportional to the reservoir density of states and contact transparency. Projecting the resulting \({H}_{{\rm{eff}}}(\omega )={H}_{0}+\Sigma (\omega )\) onto the Majorana basis yields the \({H}_{{\rm{M}}}\) of Eq. (2). In our microscopic calculations, we solve the effective problem \({H}_{{\rm{eff}}}(0){\psi }_{\pm }=\varepsilon {\psi }_{\pm }\), which gives the complex eigenvalues and eigenstates discussed in the main text. Non-trivial zero modes are characterised by a non-Hermitian topological invariant given by the sign of normalised difference \(({\gamma }_{0}-| {E}_{0}| )/{\Gamma }_{0}\). This criterion crucially depends on the wave function asymmetry near the contact, which is given by the expression

Transport

Transport and spectral observables are computed by solving the retarded Green function \(G\) of the contact. From \(G\) one may obtain the local density of states, the scattering matrix, and all the other observables presented. The poles of the scattering matrix are also poles of \(G(\omega )\) in the lower-half complex plane. These are evaluated in practice by finding the nullspace of \({G}^{-1}(\omega )=[\omega -{H}_{{\rm{eff}}}(\omega )]\). The differential conductance \({d}I/{d}V\) is obtained41 by computing the scattering matrix of the normal-superconductor contact through the Lippmann-Schwinger equation, resolving it into particle and hole sectors, and applying the Blonder-Tinkham-Klapwijk formalism42 for the \({d}I/{d}V\), which explicitly reads:

Here, \({\mathcal{N}}\) is the number of propagating channels in the normal side at energy \(\epsilon =V\), and \({r}_{{\rm{ee}}}\) and \({r}_{{\rm{eh}}}\) are the corresponding normal and Andreev reflection matrices (for full details see section 1 in the Supplemental Information of Ref. 10). Although it is not strictly a non-equilibrium technique, this method is equivalent to other techniques such as the Keldysh-Nambu Green’s function approach43 when computing the subgap conductance in the absence of relaxation processes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kitaev, A. Y. Unpaired Majorana fermions in quantum wires. Phys. Usp. 44, 131 (2001).

Lutchyn, R. M., Sau, J. D. & Sarma, S. D. Majorana fermions and a topological phase transition in semiconductor-superconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 077001 (2010).

Oreg, Y., Refael, G. & vonOppen, F. Helical liquids and Majorana bound states in quantum wires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 177002 (2010).

Mourik, V. et al. Signatures of Majorana fermions in hybrid superconductor-semiconductor nanowire devices. Science 336, 1003–1007 (2012).

Deng, M. T. et al. Majorana bound state in a coupled quantum-dot hybrid-nanowire system. Science 354, 1557–1562 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Quantized Majorana conductance. Nature 556, 74 EP - (2018).

Aguado, R. Majorana quasiparticles in condensed matter. Riv. Nuovo Cimento 40, 523–593 (2017).

Lutchyn, R. M. et al. Majorana zero modes in superconductor-semiconductor heterostructures. Nat. Rev. Materials 3, 52–68 (2018).

Kells, G., Meidan, D. & Brouwer, P. W. Near-zero-energy end states in topologically trivial spin-orbit coupled superconducting nanowires with a smooth confinement. Phys. Rev. B 86, 100503 (2012).

Prada, E., San-Jose, P. & Aguado, R. Transport spectroscopy of ns nanowire junctions with Majorana fermions. Phys. Rev. B 86, 180503(R) (2012).

Liu, C. X., Sau, J. D. & Sarma, S. D. Role of dissipation in realistic Majorana nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 95, 054502 (2017).

Moore., C., Stanescu, T. D. & Tewari, S. Two-terminal charge tunneling: disentangling Majorana zero modes from partially separated andreev bound states in semiconductor-superconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 97, 165302 (2018).

Moore, C., Zeng, C., Stanescu, T. D. & Tewari, S. Quantized zero bias conductance plateau in semiconductor-superconductor heterostructures without non-abelian Majorana zero modes. Phys. Rev. B 98, 155314 (2018).

Vuik, A., Nijholt, B., Akhmerov, A. R. & Wimmer, M. Reproducing topological properties with quasi-Majorana states. arXiv:1806.02801 (2018).

Prada, E., Aguado, R. & San-Jose, P. Measuring Majorana nonlocality and spin structure with a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 96, 085418 (2017).

Schuray, A., Weithofer, L. & Recher, P. Fano resonances in Majorana bound states-quantum dot hybrid systems. Phys. Rev. B 96, 085417 (2017).

Peñaranda, F., Aguado, R., San-Jose, P. & Prada, E. Quantifying wave-function overlaps in inhomogeneous Majorana nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 98, 235406 (2018).

Deng, M.-T. et al. Nonlocality of Majorana modes in hybrid nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 98, 085125 (2018).

Gong, Zongping et al. Topological phases of non-hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031079 (2018).

Bandres, M. A. & Segev, M. Viewpoint: non-hermitian topological systems. Physics 11, 96 (2018).

Kawabata, K., Higashikawa, S., Gong, Z., Ashida, Y. & Ueda, M. Topological unification of time-reversal and particle-hole symmetries in non-hermitian physics. Nat. Commun. 10, 297 (2019).

Shen, H., Zhen, B. & Fu, L. Topological band theory for non-hermitian hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 146402 (2018).

Pikulin, D. I. & Nazarov, Y. V. Topological properties of superconducting junctions. JETP Lett. 94, 693–697 (2012).

Pikulin, D. I. & Nazarov, Y. V. Two types of topological transitions in finite Majorana wires. Phys. Rev. B 87, 235421 (2013).

Berry, M. V. Physics of nonhermitian degeneracies. Czech. J. Phys. 54, 1039–1047 (2004).

Heiss, W. D. The physics of exceptional points. J. Phys. A 45, 444016 (2012).

Zhen, B. et al. Spawning rings of exceptional points out of Dirac cones. Nature 525, 354–358 (2015).

Poli, C., Bellec, M., Kuhl, U., Mortessagne, F. & Schomerus, H. Selective enhancement of topologically induced interface states in a dielectric resonator chain. Nat. Commun. 6 (2015).

Zhou, H. et al. Observation of bulk Fermi arc and polarization half charge from paired exceptional points. Science 359, 1009–1012 (2018).

Kozii, V. & Fu, L. Non-hermitian topological theory of finite-lifetime quasiparticles: prediction of bulk Fermi arc due to exceptional point. arXiv:1708.05841 (2017).

Leykam, D., Bliokh, K. Y., Huang, C., Chong, Y. D. & Nori, F. Edge modes, degeneracies, and topological numbers in non-hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 040401 (2017).

Zyuzin, A. A. & Zyuzin, A. Y. Flat band in disorder driven non-hermitian Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 97, 041203 (2018).

Zyuzin, A. A. & Simon, P. Disorder-induced exceptional points and nodal lines in Dirac superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 99, 165145 (2019).

Lee, E. J. H. et al. Spin-resolved Andreev levels and parity crossings in hybrid superconductor-semiconductor nanostructures. Nat. Nano 9, 79–84 (2014).

Dietz, B. et al. Rabi oscillations at exceptional points in microwave billiards. Phys. Rev. E 75, 027201 (2007).

Heiss, W. D. Time behaviour near to spectral singularities. Eur. Phys. J. D 60, 257–261 (2010).

Nichele, F. et al. Scaling of Majorana zero-bias conductance peaks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 136803 (2017).

Ioselevich, P. A. & Feigel’man, M. V. Tunneling conductance due to a discrete spectrum of Andreev states. New J. Phys. 15, 055011 (2013).

Cayao, J., Prada, E., San-Jose, P. & Aguado, R. Sns junctions in nanowires with spin-orbit coupling: role of confinement and helicity on the subgap spectrum. Phys. Rev. B 91, 024514 (2015).

San-Jose, P., Cayao, J., Prada, E. & Aguado, R. Majorana bound states from exceptional points in non-topological superconductors. Sci. Rep. 6, 21427 (2016).

San-Jose, P. MathQ, a Mathematica simulator for quantum systems, Http://www.icmm.csic.es/sanjose/MathQ/MathQ.html.

Blonder, G. E., Tinkham, M. & Klapwijk, T. M. Transition from metallic to tunneling regimes in superconducting microconstrictions: excess current, charge imbalance, and supercurrent conversion. Phys. Rev. B 25, 4515–4532 (1982).

Cuevas, J. C., Martín-Rodero, A. & Yeyati, A. L. Hamiltonian approach to the transport properties of superconducting quantum point contacts. Phys. Rev. B 54, 7366–7379 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Cayao for useful discussions in the early stages of this work. Research supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities through Grants PGC2018-097018-B-I00, FIS2015-65706-P, FIS2015-64654-P, FIS2016-80434-P (AEI/FEDER, EU), the FPI programme BES-2016-078122, the Ramón y Cajal programme Grants RYC-2011-09345, RYC-2013-14645, the María de Maeztu Programme for Units of Excellence in R&D (MDM-2014-0377), and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the FETOPEN Grant Agreement No. 828948. We also acknowledge support from CSIC Research Platform on Quantum Technologies PTI-001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A. conceived the idea and supervised the research. J.A. and F.P. performed numerics and prepared figures. J.A., F.P., E.P., P.S.-J. and R.A. contributed to the scientific discussion and provided scientific insight . E.P., P.S.-J. and R.A. wrote the manuscript with input from J.A. and F.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Avila, J., Peñaranda, F., Prada, E. et al. Non-hermitian topology as a unifying framework for the Andreev versus Majorana states controversy. Commun Phys 2, 133 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0231-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0231-8

This article is cited by

-

Subgap spectroscopy along hybrid nanowires by nm-thick tunnel barriers

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Conductance spectroscopy of Majorana zero modes in superconductor-magnetic insulator nanowire hybrid systems

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Majorana-like Coulomb spectroscopy in the absence of zero-bias peaks

Nature (2022)

-

Modified Bogoliubov-de Gennes treatment for Majorana conductances in three-terminal transports

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2022)

-

Topological isoconductance signatures in Majorana nanowires

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.