Abstract

Different fields of physics characterize differently how much two quantum operations disagree: quantum information theory features uncertainty relations cast in terms of entropies. The higher an uncertainty bound, the less compatible the operations. In condensed matter and high-energy physics, initially localized, far-apart operators come to disagree as entanglement spreads through a quantum many-body system. This spread, called “scrambling,” is quantified with the out-of-time-ordered correlator (OTOC). We unite these two measures of operation disagreement by proving entropic uncertainty relations for scrambling. The uncertainty bound depends on the quasiprobability (the nonclassical generalization of a probability) known to average to the OTOC. The quasiprobability strengthens the uncertainty bound, we find, when a spin chain scrambles in numerical simulations. Hence our entropic uncertainty relations reflect the same incompatibility as scrambling, uniting two fields’ notions of quantum-operation disagreement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

How incompatible are two quantum operators, \(\hat V\) and \(\hat W(t)\)? Two species of quantum physicist answer with two different measures. Today’s pure quantum information (QI) theorist checks uncertainty relations cast in terms of entropies1. The greater the uncertainty bounds, the worse the operators’ disagreement.

The second species—the condensed-matter or high-energy physicist—studies the following set-up: consider a strongly coupled quantum many-body system. Examples include an interacting spin chain and the dual of a gravitational theory. The Hamiltonian, \(\hat H\), couples the subsystems and generates the time-evolution operator \(\hat U: = e^{ - i\hat Ht}\). Let \(\hat V\) and \(\hat W\) denote Hermitian and/or unitary operators localized on far-apart subsystems. Examples include Pauli operators acting on opposite sides of the spin chain. In the Heisenberg picture, the interactions delocalize \(\hat W\) to \(\hat W(t): = \hat U^\dagger \hat W\hat U\). The support of \(\hat W(t)\) comes to overlap the support of \(\hat V\); the operators cease to agree. This disagreement is diagnosed with the out-of-time-ordered correlator (OTOC), which also signals quantum chaos and QI scrambling2. QI scrambles upon spreading across a system via many-body entanglement.

Entropic uncertainty relations and OTOCs occupy disparate subfields, but both quantify operator disagreement. We unite these quantifications, proving entropic uncertainty relations for QI scrambling [Eqs. (24) and (25)]. These relations make precise the extent to which scrambling drives operators away from compatibility. The relations can be tested experimentally, with superconducting qubits, quantum dots, trapped ions, and perhaps nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). We evaluate our uncertainty relations in numerical simulations of nonintegrable spin chains. The uncertainty bounds tighten when the system scrambles, confirming that entropic uncertainty relations can reflect the type of operator incompatibility behind scrambling. We then generalize our entropic uncertainty relations in two ways. First, we extend the relations from the most famous OTOC to arbitrarily high-order correlators with arbitrary time orderings. Such OTOCs reflect later, subtler stages of scrambling and equilibration3,4,5,6,7. Second, we generalize beyond many-body systems that scramble. Our uncertainty relations for scrambling can be tested experimentally with weak measurements, which barely disturb the measured system8. Weak measurements are used to measure weak values, expectation values conditioned on preselection and postselection9. We unveil a physical significance of weak values: They govern first-order-in-the-weak-coupling terms in entropic uncertainty bounds [Eqs. (39) and (40)]. These bounds govern weak-measurement experiments undertaken routinely.

Results

Entropic uncertainty relations

We will briefly overview entropic uncertainty relations and OTOCs. Then, we reason intuitively to the form that entropic uncertainty relations for scrambling should assume. This intuition is then made rigorous: We concretize the set-up, then formalize the measurements. The measurements’ possible outcomes obey probability distributions whose entropies we then define. We then present and analyze the entropic uncertainty relations for scrambling. Numerical simulations of a spin chain illustrate the results in the Methods section. We generalize to higher-point OTOCs, then to weak values beyond scrambling.

Heisenberg captured the complementarity of position and momentum in ref. 10. Kennard concretized this complementarity in the first uncertainty relation11. Robertson proved the uncertainty relation featured in many textbooks12:

We have set ħ to one. \(\hat A\) and \(\hat B\) denote observables defined on a Hilbert space \({\cal{H}}\). The expectation value 〈.〉 is evaluated on a state \(\left| \psi \right\rangle \in {\cal{H}}\). The standard deviation \(\Delta \hat A: = \sqrt {\langle \hat A^2\rangle - \langle \hat A\rangle ^2}\) quantifies the spread in the possible outcomes of a measurement of \(\hat A\).

The standard deviations have provoked objections (e.g., ref. 13). For example, consider relabeling the eigenvalues a of \(\hat A\). Relabeling should not change the operators’ compatibility, but \({\mathrm{\Delta }}\hat A\) can skyrocket. Stripping the a’s off of \({\mathrm{\Delta }}\hat A\) leaves a function of probabilities: Denote by pa the probability that a measurement of \(\hat A\) yields a. On probability distributions pa are defined entropies. Entropies, the workhorses of information theory, quantify the optimal rates at which information-theoretic and thermodynamic tasks can be performed14,15. Entropies replace standard deviations in modern uncertainty relations1.

The Maassen–Uffink relation exemplifies entropic uncertainty relations16:

The Shannon entropy is defined as \(H(\hat A): = - \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_a {p_a} \,{\mathrm{log}}\,p_a\). The maximum overlap c is defined in terms of the eigendecompositions

as

Hence, the bound (2) is independent of the eigenvalues a, as desired. The bound is tight if c is small. c is smallest when the eigenbases are mutually unbiased: \(\left| {\left\langle {a|b} \right\rangle } \right| = \frac{1}{{\sqrt d }}\), wherein \(d: = {\mathrm{dim}}({\cal{H}})\) denotes the Hilbert space’s dimensionality. For example, the Pauli operators \(\hat \sigma ^x\) and \(\hat \sigma ^z\) have mutually unbiased eigenbases. If you prepare any eigenstate of \(\hat \sigma ^x\), then measure \(\hat \sigma ^z\), you have no idea which outcome will obtain. Hence, \(\hat \sigma ^x\) and \(\hat \sigma ^z\) are said to fail maximally to commute. Entropic uncertainty relations have applications to many topics in quantum theory, including quantum correlations, steering, coherence, and wave-particle duality (see ref. 1 and references therein).

Out-of-time-ordered correlators

OTOCs reflect chaos and QI spreading in quantum many-body systems. Settings range from ultracold atoms and trapped ions to holographic black holes2. Let \({\cal{H}}\) denote a quantum many-body system’s Hilbert space. Let \(\hat \rho \in {\cal{D}}({\cal{H}})\) denote an arbitrary state of the system. \({\cal{D}}({\cal{H}})\) denotes the space of density operators, or trace-one positive-semidefinite linear operators, defined on \({\cal{H}}\). The OTOC has the form

for unitary and/or Hermitian \(\hat V\) and \(\hat W\) localized far apart. The OTOC forms the nontrivial component of

This magnitude-squared commutator equals 2[1 − F(t)] if \(\hat V\) and \(\hat W\) are unitary (e.g., Pauli operators).

Several pieces of evidence imply that the OTOC signals chaos. We review a semiclassical argument about the butterfly effect: Classical chaos hinges on sensitivity to initial perturbations. Consider initializing a classical double pendulum at a phase-space point P with a strong kick. Let the pendulum begin another trial at a nearby point P + ε. The pendulum follows different phase-space trajectories in the two trials. The trajectories diverge exponentially, as quantified with a Lyapunov exponent λL.

The OTOC captures a similar divergence. Let us construct two protocols that differ largely by an initial perturbation. The system could consist of an N-site chain of spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\) degrees of freedom, or qubits. Suppose that \(\hat \rho = \left| \psi \right\rangle \left\langle \psi \right|\) is pure. Protocol I consists of (i) preparing the system in |ψ〉, (ii) perturbing the system with a local \(\hat V\) (as by flipping spin 1 with \(\hat \sigma _1^x\)), (iii) evolving the system under a nonintegrable Hamiltonian, (iv) perturbing with a local \(\hat W\) (such as the final spin’s \(\hat \sigma _N^z\)), and (v) evolving the system backward, under \(\hat U^\dagger\). This protocol prepares \(\left| {\psi _{\mathrm{I}}} \right\rangle : = \hat W(t)\hat V\left| \psi \right\rangle\).

Following protocol II, one prepares |ψ〉 and skips the initial \(\hat V\). The system evolves forward under \(\hat U\), is perturbed with \(\hat W\), and reverse-evolves under \(\hat U^\dagger\). Only afterward does \(\hat V\) perturb the system. Protocol II prepares \(\left| {\psi _{{\mathrm{II}}}} \right\rangle : = \hat V\hat W(t)\left| \psi \right\rangle\).

How much does the initial \(\hat V\) perturbation affect the system’s final state? The answer manifests in the overlap

Nonlocal systems, such as the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev (SYK) model17,18,19,20, obey the final relation. [In local systems, F(t) decays polynomially.] The relation holds during a time window around the “scrambling time,” t*. The Lyapunov-type exponent λ controls the exponential decay. Hence, F(t) reflects a Lyapunov-type divergence reminiscent of classical-chaotic sensitivity to initial perturbations.

Smallness of F(t) tends to reflect highly nonlocal entanglement. After t*, no local probe \(\hat V\) can recover information about any earlier, initially local perturbation \(\hat W\). This many-body nonlocality is QI scrambling21,22,23.

Intuitive construction of entropic uncertainty relations for scrambling

Uncertainty relations and OTOCs, reflecting quantum operator disagreement in different subfields, cry out for unification. However, how can one form an uncertainty relation for scrambling? One might try substituting \(\hat A = \hat V\) and \(\hat B = \hat W(t)\) into the uncertainty relation (2). However, the bound would bear no signature of scrambling. Moreover, simulations imply, simple choices of \(\hat V\) and \(\hat W(t)\) eigenbases fail to become mutually unbiased after t*5.

A clue suggests how entropic uncertainty relations for scrambling may be realized: The entropic inequality (2) replaced the textbook inequality (1). Inequality (1) contains one commutator. The OTOC appears in a commutator’s squared magnitude [Eqs. (5) and (6)]. Hence squaring, in some sense, Eq. (2) might yield an entropic uncertainty relation for scrambling.

How might this sort of squaring manifest? In the left-hand side (LHS) of Eq. (2), each entropy H depends on one operator, \(\hat A\) or \(\hat B\). Imagine doubling each operator by replacing it with two operators. The two operators suited to scrambling are \(\hat V\) and \(\hat W(t)\). We therefore envision an entropy \(H(\hat V\hat W(t))\) defined in terms of a measurement of \(\hat V\) followed by a measurement of \(\hat W(t)\). This replacement for \(H(\hat A)\) must differ from the replacement for \(H(\hat B)\), but the OTOC contains only two local operators. We therefore reverse the measurements: \(H(\hat B) \to H(\hat W(t)\hat V)\). The reversal mirrors the OTOC’s semiclassical interpretation, Eq. (7).

How can the right-hand side (RHS) of Eq. (2) be squared in the right sense? c equals a product of two inner products. Squaring c creates a product of four inner products, or the trace of four outer products |…〉〈…|. Outer products generalize to projectors Π. Hence a trace of a product of four projectors, Tr(ΠΠΠΠ), should appear in an entropic uncertainty bound for scrambling. Such a trace is known to characterize scrambling. It forms the quasiprobability behind the OTOC5,24,25.

Quasiprobability distributions represent quantum states as probability distributions represent classical statistical-mechanical states. Like probabilities, quasiprobabilities are normalized to one. Yet quasiprobabilities violate axioms of probability theory, such as nonnegativity and reality. Such nonclassical behaviors can signal nonclassical physics, such as the capacity for superclassical computation26.

The OTOC equals an average over a quasiprobability distribution defined as follows in refs. 5,24. The OTOC operators eigendecompose as

In the spin-chain example, the eigenvalues \(v_\ell ,w_m = \pm 1\). The projector \(\hat \Pi _{v_\ell }^{\hat V}\) projects onto the eigenvalue-\(v_\ell\) eigenspace of \(\hat V\). \(\hat \Pi _{w_m}^{\hat W(t)}\) is defined analogously. Consider substituting from Eq. (8) into the OTOC definition (5). Factoring out the sums and the eigenvalues yields

The index list (v1, w1, v2, w2) here is equivalent to the index list (v1, w2, v2, w3) in5,24. The OTOC equals an average over the OTOC quasiprobability:

The quasiprobability forms a distribution \(\{ \tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{\hat \rho }\}\). This set of numbers contains more information than the OTOC, which follows from coarse-graining the quasiprobability. Recent studies have uncovered several theoretical and experimental applications of the quasiprobability: \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{\hat \rho }\) concretizes the relationship between scrambling and nonequilibrium statistical mechanics24, informs schemes for measuring the OTOC experimentally5,6,24, distinguishes scrambling from decoherence in measurements of open-system OTOCs25, and underlies a quantum advantage in metrology27. This paper introduces another application of the OTOC quasiprobability: \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{ \hat{\mathbb{1}} }\) governs terms in the entropic uncertainty bound for scrambling. The quasiprobability tightens the bound when the system scrambles. We evaluate the quasiprobability on the identity operator \(\hat{\mathbb{1}}\) because entropic uncertainty bounds cannot depend on any state \(\hat \rho\). Uncertainty relations require, moreover, that eigenvalues be stripped off of operators. \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{ \hat{\mathbb{1}} }\) follows from stripping the eigenvalues off the OTOC, by Eq. (9).

We can predict the form of the uncertainty-bound term that will contain \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{ \hat{ \mathbb{1}} }\). Quasiprobabilities can be measured via weak measurement: an interaction Hamiltonian couples a detector to the system. A small coupling constant g governs the interaction. The measurement disturbs the measured state at high order in g. From weak and strong measurements of \(\hat V\) and \(\hat W(t)\), the OTOC quasiprobability can be inferred experimentally5,6,24. \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{\hat \rho }\) is extracted from the data through a high-order term. \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{ \hat{\mathbb{1}} }\) should therefore appear in a high-order-in-g term in our entropic uncertainty bound.

The OTOC uncertainty relation’s RHS will contain g only if the LHS involves weak measurements. Consider measuring \(\hat V\) weakly, then \(\hat W(t)\) strongly. Each possible pair \((v_\ell ,w_m)\) of outcomes has some probability of obtaining. On this probability, we propose to define the entropy \(H(\hat V\hat W(t))\). \(H(\hat W(t)\hat V)\) should be defined similarly.

Let us summarize our intuitive reasoning. Entropic uncertainty relations for scrambling should have the form

The exponent k ≥ 2. \(H(\hat V\hat W(t))\) quantifies the uncertainty about the outcomes that follow from preparing an arbitrary \(\hat \rho\), measuring \(\hat V\) weakly, and then measuring \(\hat W(t)\) strongly. \(H(\hat W(t)\hat V)\) results from reversing the measurement protocol. Having constructed expectations via intuition, we now prove them.

Set-up

We continue to focus on a quantum many-body system illustrated with a chain of N qubits. To simplify notation, we omit hats from operators. Many-body quantities are defined as in the introduction: the Hilbert space \({\cal{H}}\), its dimensionality d, the arbitrary state \(\rho \in {\cal{D}}({\cal{H}})\), the Hamiltonian H, the time-evolution unitary U, the local operators V and W (illustrated with \(\sigma _1^z\) and \(\sigma _N^z\)), the Heisenberg-picture W(t), the projectors \(\Pi^V_{v_\ell}\) and \(\Pi^{W(t)}_{w_m}\), the eigenvalues \(v_\ell\) and wm, the OTOC F(t), and the OTOC quasiprobability \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_\rho\).

The Hilbert space \({\cal{H}}\) is assumed to be discrete, in accordance with refs. 28,29, whose results we use. Continuous-variable systems are addressed in the Discussion. We emphasize nonintegrable, nonlocal Hamiltonians. We assume that V and W are Hermitian, for simplicity, but the results generalize: each of V and W can be Hermitian and/or unitary5,24. If V is unitary but not Hermitian, for example, measurements of V are replaced with measurements of the Hermitian generator of V.

Formalization of measurements

A sequence of V and W(t) measurements forms a generalized measurement. Generalized measurements are formalized, in QI theory, with positive operator-valued measures (POVMs)30. A POVM {Mx} consists of positive operators Mx > 0 that obey the completeness condition \(\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_x {M_x^\dagger } M_x = {\mathbb{1}}\). x labels the outcomes.

POVMs replace measurements of observables A and B in generalized entropic uncertainty relations28,29. We adapt the formalism used by Tomamichel28, for concreteness and for ease of comparison with a standard reference. In ref. 28 appear POVMs illustrated with measurements of observables.

These general POVMs manifest, in the context of scrambling, as follows. We label as “the forward POVM” a weak measurement of V, followed by a projective measurement of W(t). We use the term “weak measurement of V” as in ref. 5: A projector \(\Pi _{v_1}^V\) is effectively measured weakly. One can effectively measure a qubit system’s \(\Pi _{v_1}^V\) by, e.g., coupling the detector to V and calibrating the detector appropriately. The experimenter chooses the value of v1; the choice directs the calibration. See the spin-chain set-up in the Methods, as well as ref. 5, Sec. I D 4, for example implementations. The reverse process constitutes the second POVM, for a definition of “reverse” that we concretize after formalizing the weak measurement.

To measure \(\Pi _{v_\ell }^V\) weakly, one prepares a detector in a state |D〉. The system’s \(\Pi _{v_\ell }^V\) is coupled weakly to a detector observable, via an interaction unitary Vint. A detector observable is measured projectively, yielding an outcome \(j_\ell\).

The weak measurement induces dynamics modeled with Kraus operators30. Kraus operators represent the system-of-interest evolution effected by a coupling to an ancilla, which effectively measures the system:

The operators satisfy the completeness relation \( \mathop {\sum}\limits_{j_\ell } {(K_{j_\ell }^{V,v_\ell })} ^\dagger K_{j_\ell }^{V,v_\ell } = {\mathbb{1}}\). Let ρ temporarily denote the system’s precoupling state. The detector has a probability \({\mathrm{Tr}}(K_{j_\ell }^{V,v_\ell }\rho [K_{j_\ell }^{V,v_\ell }]^\dagger )\) of registering the outcome \(j_\ell\). The outcome-dependent \(g_{j_\ell }^V \in {\Bbb C}\) quantifies the interaction strength. The experimenter can tune \(g_{j_\ell }^V\), whose smallness reflects the measurement’s weakness: \(\left| {g_{j_\ell }^V} \right| \ll 1\). We refer to various constants \(g_{j_\ell }^V\) as g’s.

Imagine strongly measuring the detector observable without having coupled the detector to the system. The outcome \(j_\ell\) has a probability \(p_{j_\ell }^V\) of obtaining. We invoke Kraus operators’ unitary equivalence30 to ensure that \(p_{j_\ell }^V \in {\Bbb R}\).

The forward POVM \(M_{j_1,w_1}^{{\mathrm{F}},{v}_{\mathrm{1}}}\) is defined through the composite Kraus operators

Recall that \(\Pi _{w_1}^{W(t)}\) projects onto the w1 eigenspace of W(t). Each POVM element has the form \(\left( {\sqrt {M_{j_1,w_1}^{{\mathrm{F}},{v}_{\mathrm{1}}}} } \right)^\dagger \sqrt {M_{j_1,w_1}^{{\mathrm{F}},{v}_{\mathrm{1}}}}\).

The reverse POVM, \(\left\{ {M_{j_2,w_2}^{{\mathrm{R}},{v}_{\mathrm{2}}}} \right\}\), is defined through the composite Kraus operators

To round out the reversal, we not only swap the V measurement with the W(t), but also Hermitian-conjugate. The conjugation negates imaginary numbers. It represents, e.g., the time-reversal of magnetic fields.

Let us clarify which variables are chosen and which vary randomly. w1 is a random outcome whose value varies from realization to realization of the forward POVM. w2 is a random outcome whose value varies from realization to realization of the reverse POVM. The experimentalist chooses the values of v1 and v2. Although a forward trial’s v1 and w1 can differ from a reverse trial’s v2 and w2, both protocols’ measurements [of V and of W(t)] are essentially the same.

Entropies

Consider preparing the system in the state ρ, then measuring the forward POVM, \(\left\{ {M_{j_1,w_1}^{{\mathrm{F}},{v}_{\mathrm{1}}}} \right\}\). One prepares a detector in some fiducial state. Some detector observable is effectively coupled to the system’s \(\Pi _{v_1}^V\). Then, some detector observable couples to a classical register. (“Classical” means, here, that the register can occupy only quantum states representable by density matrices diagonal with respect to a fixed basis.) The register records an outcome j1. Next, the system’s W(t) couples to another classical register. This register records the outcome w1.

The two-register system ends in the state

The eigenvalues, \({\mathrm{Tr}}\left( {\sqrt {M_{j_1,w_1}^{{\mathrm{F}},{v}_{\mathrm{1}}}} \rho \sqrt {M_{j_1,w_1}^{{\mathrm{F}},{v}_{\mathrm{1}}}}}^{\mathrm{\dagger } }\right)\), form a probability distribution over the possible pairs (j1, w1) of measurement outcomes. Entropies of the distribution equal entropies of ρF. [In defining the entropies, we mostly follow Tomamichel’s conventions28. Yet we assume that all states σ are normalized: Tr(σ) = 1.]

The order-α Rényi entropy of a quantum state σ is

We choose for all logarithms to be base-2, following ref. 28. The von Neumann entropy is

The min entropy is defined as

pmax denotes the greatest eigenvalue of σ.

The max entropy is

The Schatten 1-norm is denoted by ||.||1. The general Schatten p-norm of a Hermitian operator \(\sigma = \mathop {\sum}\limits_j {s_j} | s_j \rangle \langle s_j |\) is

for p ≥ 131. Hmax reflects the discrepancy between σ and the maximally mixed state (p. 60 of ref. 28): The fidelity between normalized states σ and γ is \(F(\sigma ,\gamma ): = \left\| {\sqrt \sigma \sqrt \gamma } \right\|_1\). Hmax depends on the fidelity through Hmax(σ) = log(d[F(σ, 1/d)]2). [Tomamichel uses the generalized fidelity. When we evaluate the generalized fidelity, at least one argument is normalized. The generalized fidelity therefore simplifies to the fidelity (p. 48 of ref. 28).]

We notate the detector state’s Rényi entropies as

following ref. 28. We have now introduced the forward-POVM entropies. The two-detector state ρR, and the entropy Hα(W(t)V), are defined analogously.

Hmax and Hmin, like HvN, quantify rates at which information-processing and thermodynamic tasks can be performed. Applications include quantum key distribution, randomness extraction, erasure, work extraction, and work expenditure (e.g., refs. 14,15,32). Quantum states desired for such tasks cannot be prepared exactly. A process called “smoothing” introduces an error tolerance ε ∈ [0, 1) into the entropies32. Our uncertainty relations for scrambling generalize to smooth entropies. We focus on nonsmooth entropies for simplicity.

Entropic uncertainty relations for QI scrambling

We can now reconcile the two notions of quantum operator disagreement, entropic uncertainty relations of pure QI theory and information scrambling of high-energy and condensed-matter theory. The forward and reverse POVMs satisfy entropic uncertainty relations for scrambling,

and

for \(\frac{1}{\alpha} + \frac{1}{\beta} = 2\). The bound depends on the OTOC quasiprobability:

The real numbers C, and the rest of the ~g2 terms, depend essentially on classical probabilities. Their forms are given below. The j and w dependences of the C’s have been suppressed for conciseness. Inequality (25) can be smoothed when (α, β) = (∞, 1/2).

The uncertainty relations are proved in Supplementary Note 1. They follow from three general uncertainty relations: Result 7 in ref. 28, Corollary 2.6 in ref. 29, and Eq. (13) in ref. 33. The OTOC POVMs (13) and (14) are substituted into the general uncertainty relations. The POVMs’ maximum overlap, c, cannot obviously be inferred from parameters chosen, or from measurements taken, in an OTOC-inference experiment. We therefore bound c, using \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_\rho\) and the Schatten p-norm’s monotonicity in p:

We substitute in for the K’s from Eq. (12), then multiply out. In each of several terms, two K’s contribute \(\Pi _{v_\ell }^V\)’s, while two K’s contribute 1’s. These terms contain quasiprobaiblity values \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{\mathbb{1}}\). We isolate the terms by Taylor-expanding the logarithm in the g’s.

Analysis

Four points merit analysis: the POVMs’ implications for the butterfly effect, the form of the bound f(v1, v2), simple limits, and conditions that render the bound nontrivial. Numerical simulations support our analytical results; see the Methods section.

We begin with implications for the butterfly effect. The weak measurements strengthen an analogy between the OTOC and the butterfly effect of classical chaos34,35. In the classical butterfly effect, a tiny perturbation snowballs into a drastic change. This perturbation has been likened to operation by a unitary V, in Eq. (7). V should be associated with a weak measurement, our uncertainty relations clarify. The measurement is perturbative in \(g_{j_\ell }^V\).

Now, we analyze the form of the uncertainty bound f(v1, v2) for scrambling. The bound (26) contains three terms dependent on the quasiprobability \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{\mathbb{1}}\). These terms’ proportionality to g2 accords with intuition: Scrambling is a subtle feature of quantum equilibration, detectable in many-point correlators. Likewise, the OTOC quasiprobability governs high-order terms in the uncertainty bound. As anticipated in the Intuitive construction subsection of the Results, the quasiprobability \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{\mathbb{1}}\) is evaluated on the identity operator. The bound highlights the operator disagreement without pollution by any state ρ.

The quasiprobability-free terms in Eq. (26) are background terms: they contain classical probabilities, accessible without weak measurements. The g-independent term,

dominates f(v1, v2). The Kronecker delta is denoted by \(\delta _{w_1w_2}\). The two linear terms,

depend on projectors Π only through classical probabilities \(p(v_\ell |w_m) = {\mathrm{Tr}}\left( {\Pi _{v_\ell }^V \Pi _{w_m}^{W\left( t \right)}} \right){\mathrm{/Tr}}\left( {\Pi _{w_m}^{W(t)}} \right)\). This \(p(v_\ell |w_m)\) equals the conditional probability that, if the system begins maximally mixed over the wm eigenspace of W(t), if V is measured, outcome \(v_\ell\) will obtain. Such classical dependence characterizes also the g2 terms suppressed in Eq. (26),

The dominance of C0, the \(\delta _{w_1w_2}\) in C0, and the min ensure that w1 = w2 throughout the min’s argument. The first \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{\mathbb{1}}\) has four arguments, (v1, w1, v2, w2), constrained only by the \(\delta _{w_1w_2}\). In each other \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{\mathbb{1}}\), the first argument must equal the third, even before the minimization is imposed. For example, the second quasiprobability value has the form \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{\mathbb{1}}\)(v1, w1, v1, w2). The V eigenvalues equal each other, due to Eq. (27). One v1 comes from the \(\left( {K_{j_1}^{V, v_1}} \right)^\dagger\), and one, from the \(K_{j_1}^{V,v_1}\).

Now, we analyze the conditions under which the uncertainty bounds are nontrivial. The Rényi entropies are nonnegative: Hα(σ) ≥ 0. Hence, the bound is nontrivial when positive: f(v1, v2) > 0. When the coupling is weak, the bound is positive when its first term is positive. The first term simplifies to \({\mathrm{min}}_{j_1,j_2,w_2}\left\{ { - {\mathrm{log}}\left( {p_{j_1}^Vp_{j_2}^V{\mathrm{Tr}}\left( {\Pi _{w_2}^W} \right)} \right)} \right\}\). The trace is large in the system size, equaling 2N−1 in the spin-chain example. One might worry that this trace swells the log, drawing the bound far below zero.

The probabilities \(p_{j_\ell }^V\) can offset the enormity. Let us focus on the spin-chain example and approximate \(p_{j_1}^V \approx p_{j_2}^V \equiv p_{j_\ell }^V\). Nonnegativity of the log term becomes equivalent to \(\left( {p_{j_\ell }^V} \right)^22^{N - 1} \le 1\), or \(p_{j_\ell }^V \le \frac{1}{{2^{(N - 1)/2}}}\). Strongly measuring a weak-measurement detector must yield one of ≥2(N−1)/2 possible outcomes.

Weak measurements as in ref. 9 satisfy this requirement. Let each detector manifest as a particle, e.g., in a potential that defines a dial. Let O denote the strongly measured detector observable (e.g., the position \(\hat x\)). Let \(\tilde O\) denote the conjugate observable (e.g., the momentum \(\hat p\)): \(\left[ {O,\tilde O} \right] = \pm i\hbar\). Let the detector be prepared in a Gaussian state that peaks sharply at some \(\tilde O\) eigenvalue (e.g., a sharp momentum-space wave packet). The probabilities \(p_{j_\ell }^V\) can be small enough that f(v1, v2) > 0. We present an example in the Methods section.

The g-free log encodes randomness in a measurement of a detector that has never coupled to the system. Hence, the log fails to reflect disagreement between V and W(t). The disagreement manifests in the g-dependent terms.

Three simple limits illuminate the bound’s behavior: early times (t ≈ 0), late times (t ≥ t*), and the weak limit (g → 0). We focus on a chaotic spin chain, for concreteness. Numerical simulations support these arguments in the Methods section.

Early times (t ≈ 0): V and W(t) ≈ W nontrivially transform just far-apart subsystems. Hence \({\mathrm{Tr}}\left( {\Pi _{w_\ell }^{W(t)}\Pi _{v_m}^V} \right) \approx 2^{N - 2}\). Also, [V, W(t)] ≈ 0, so the projectors nearly commute. Hence \({\mathrm{Tr}}\left( { \Pi _{w_m}^{W(t)} \Pi _{v_m}^V\Pi _{w_{\ell \prime }}^{W(t)}\Pi _{v_{m\prime }}^V} \right) \approx 2^{N - 2}\,\delta _{w_\ell w_{\ell \prime }}\delta _{v_mv_{m\prime }}\). These traces are large, dragging the ~g terms in Eq. (26), and the negative term in Eq. (30), below zero. The g’s mitigate the dragging’s magnitude. Still, the bound is expected to be relatively loose before t*.

Late times (t ≥ t*): V can fail to commute with W(t). Traces \({\mathrm{Tr}}\left( {\Pi _{w_\ell }^{W(t)}\Pi _{v_m}^V \ldots } \right)\) will shrink: Consider a one-qubit system, as a simple illustration. Suppose that V = σz and that W = σx. Each \(\Pi _{w_\ell }^{W(t)}\Pi _{v_m}^V\) translates roughly into a \(|\left\langle {x_\ell |z_m} \right\rangle |^2 = \frac{1}{d}\). The traces’ smallness tightens the uncertainty bound, as expected when the system is scrambled (as explained in the introduction). [This expectation is borne out when v1 = v2, as implied by (i) Supplementary Note 2 and (ii) reasoning, similar to that in the Supplementary Note, about the \(\vert g^V_ {j} \vert^2\) terms in Eq. (26). Supplementary Note 2 also shows why the quasiprobability tightens the bound when (i) v1 = −v2 and (ii) \(g^V_{j_1} g^V_{j_2}\) approximately equals a negative real number.] The bound likely does not remain at its maximum possible value at all t > t*, however. As W(t) evolves, the bound should fluctuate around a relatively large value.

Weak limit (g → 0): The system fails to couple to the detectors. The bound (26) reduces to \({\mathrm{min}}_{w_2} \left\{- {\log} \left(p^V_{j_1} p^V_{j_2}{\mathrm{Tr}}\left( \Pi^W_{w_2} \right) \right)\right\}\). The probability distribution \(\{ p^V_{j_\ell} \}\) has a spread quantified by the Shannon entropy \(H_{\rm{Sh}} ( \{ p^V_{j_\ell} \} )\). The left-hand side of Eq. (24) reduces to \(2\left[ {H_{{\mathrm{vN}}}(W(t))_\rho + H_{{\mathrm{Sh}}}\left( {\{ p_{j_\ell }^V\} } \right)} \right]\).

Extension to higher-point OTOCs

Higher-point OTOCs reflect later, subtler stages of QI scrambling and many-body equilibration. F(t) has been generalized to the \(\bar {\mathscr{K}}\)-fold OTOC3,4,5,6,7

We follow the notation in ref. 5. This \(2\bar {\mathscr{K}}\)-point correlator is labeled by \(\bar {\mathcal{K}} = 1,\,2,\,3, \ldots\) The conventional OTOC corresponds to \(\bar {\mathcal{K}} = 2\). If \(F^{(\bar {\mathcal{K}})}(t) = W(t)V \ldots \,W(t)V\), the correlator encodes \(\bar {\mathcal{K}}\) time reversals, as concretized in Schwinger-Keldysh path integrals4 and in the weak-measurement scheme5,24. Higher-point OTOCs \(F^{(\bar {\mathcal{K}})}(t)\) equilibrate at later times7 \(t_ \ast ^{({\mathcal{K}})}\sim (\bar {\mathcal{K}} - 1)t_ \ast\) and can be inferred from sequences of \(2\bar {\mathcal{K}} - 1\) weak measurements.

\(F^{(\bar {\mathcal{K}})}(t)\) equals a coarse-graining of a quasiprobability distribution5 \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_\rho ^{({\mathcal{K}})}\). \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{\mathbb{1}} ^{({\mathcal{K}})}\) governs terms \(\propto g^{2(\bar {\mathcal{K}} - 1)}\) in an entropic uncertainty relation for scrambling. Denote the eigenvalues of A(t1), B(t2), … by a,b, … Denote the eigensubspace projectors by \({\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_a^{A(t_1)},{\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_b^{B(t_2)}, \ldots _{}^{}\) The forward POVM consists of a weak measurement of \({\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_r^{R(t_{2\bar {\mathcal{K}}})}\), followed by a weak measurement of \({\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_q^{Q(t_{2\bar {\mathcal{K}} - 1})}\), and so on, until a weak measurement of \({\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_g^{G(t_{\bar {\mathcal{K}} + 2})}\), followed by a strong measurement of \(F(t_{\bar {\mathcal{K}} + 1})\). The reverse POVM consists of a strong measurement of A(t1), followed by a weak measurement of \({\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_b^{B(t_2)}\), followed by more weak measurements, until a weak measurement of \({\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_e^{E(t_{\bar {\mathcal{K}}})}\).

The weak measurement of an observable Θ = B(t2), C(t3), … is represented by a Kraus operator \(K_{j_\alpha }^{{\mathrm{\Theta }}, \theta _\alpha } = p_{j_\alpha }^{\mathrm{\Theta }}{\mathbb{1}} + g_{j_\alpha }^{\mathrm{\Theta }}{\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_\alpha ^{\mathrm{\Theta }}\). The jα denotes the weak measurement’s outcome, \(p_{j_\alpha }^{\mathrm{\Theta }}\) denotes the detector probability, and \(g_{j_\alpha }^{\mathrm{\Theta }}\) denotes the outcome-dependent weak-coupling strength.

The von Neumann uncertainty relation has the form

The term

contains the quasiprobability behind the \(\bar {\mathcal{K}}\)-fold OTOC. Entropic uncertainty relations for ≥3 measurements appear similar, prima facie. They have little relevance, however, as explained in Supplementary Note 4. Hence, our entropic uncertainty relations extend to arbitrary-point OTOCs.

Entropic uncertainty relations for weak values beyond scrambling

Weak values, like OTOCs, involve time reversals and measurement sequences9. Consider preparing a quantum system in a state i at a time t = 0, evolving the system for a time t″ under a unitary Ut″, measuring a nondegenerate observable \(F = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_f f |f\rangle \langle f|\), and obtaining the outcome f. Let \(A = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_a a |a\rangle \langle a|\) denote a nondegenerate observable that fails to commute with F.

Which value can most reasonably be attributed, retrodictively, to the A at a time t′∈(0, t″), given that |i〉 was prepared and that the measurement yielded f? The weak value,

is the expectation value conditioned on the preselection and postselection. |f′〉:= Ut′′−t′|f〉 and |i′〉:= Ut′|i〉 denote time-evolved states.

Consider eigendecomposing A, then factoring out the sum and eigenvalues. Multiplying the numerator and denominator by 〈i′|f′〉 yields

wherein p(f|i) = |〈f′|i′〉|2 denotes a conditioned probability. The numerator is a Kirkwood-Dirac quasiprobability, an extension of which is the OTOC quasiprobability5. The Kirkwood-Dirac quasiprobability governs the conditional quasiprobability 〈f′|a〉〈a|i′〉〈i′|f′〉/p(f|i) that, if |i〉 is prepared and the F measurement yields f, a is the value most reasonably attributable to A retrodictively.

Awk generalizes to arbitrary initial states ρ and to degenerate observables \(A = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_a a \,{\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_a^A\) and \(F = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_f f \,{\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_f^F\):

The time-evolved state \(\rho (t\prime ): = U_{t\prime }^\dagger \rho U_{t\prime }\), and the conditional probability \(p(f|\rho ): = {\mathrm{Tr}}\left( {{\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_f^{F(t\prime\prime - t\prime )}\rho (t\prime )} \right)\). One can infer Awk experimentally by preparing ρ, evolving the system for a time t′, measuring A weakly, evolving the system for a time t″ − t′, and measuring F strongly. One performs this protocol in many trials. Awk is inferred from the measurement statistics.

Awk can range outside the spectrum of A, as advertised in the foundational paper ref. 9. Hence, the physical significances of Awk have galvanized debate. Weak values have been interpreted in terms of conditioned expectation values9 and disturbances by measurements36. Kirkwood-Dirac quasiprobabilities have been interpreted in terms of operator decompositions and Bayesian retrodiction. We introduce another physical significance: Weak values govern first-order-in-g terms in entropic uncertainty bounds for POVMs that involve weak measurements. Kirkwood-Dirac quasiprobabilities play an analogous role in analogous bounds. We present the results, then illustrate with a qubit.

Using the foregoing background, we construct entropic uncertainty relations for weak values and Kirkwood-Dirac quasiprobabilities. Consider a quantum system associated with a Hilbert space \({\cal{H}}\). Let \(\rho \in {\cal{D}}({\cal{H}})\) denote any state of the system. Let \(A = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_a a {\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_a^A\), \(F = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_f f {\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_f^F\), and \({\cal{I}} = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i {\lambda _i} {\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_i^I\) be eigenvalue decompositions of observables. [The index i should not be confused with \(\sqrt { - 1}\). The index serves similarly to the i that labels the initial state i' in Eq. (35).]

The uncertainty relation for Awk features a POVM that we label I. One measures A weakly, then F strongly: \(\left\{ {\sqrt {M_{j,f}^{\mathrm{I}}} : = {\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_f^FK_j^A} \right\}\). The weak-measurement Kraus operator \(K_j^A = \sqrt {p_j^A} {\mathbb{1}} + g_j^AA + O\left( {g^2} \right)\). The O(g2) signifies terms of second order in the Hamiltonian’s coupling parameter (e.g., the \(\tilde g_{}^{}\) in the spin-chain example in the Methods section). We define as POVM II a strong measurement of \({\cal{I}}:\left\{ {\sqrt {M_i^{{\mathrm{II}}}} : = {\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_i^{\cal{I}}} \right\}\).

Define the entropies Hα(AF)ρ, and \(H_\alpha ({\cal{I}})_\rho\) via analogy with the QI-scrambling entropies in the Entropies subsection above. One can infer the weak value

by preparing the state \({\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_i^{\cal{I}}/{\mathrm{Tr}}\left( {{\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_i^{\cal{I}}} \right)\), measuring A weakly, and postselecting a strong F measurement on f. We have tweaked our notation for Awk. The first argument, i, labels the subspace over which the state \({\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_i^{\cal{I}}/{\mathrm{Tr}}\left( {{\mathrm{{\Pi}}}_i^I} \right)\) is maximally mixed.

POVMs I and II obey entropic uncertainty relations dependent on the weak value Awk(i,f):

and

The bound has the form

The Rényi orders α and β satisfy \(\frac{1}{\alpha } + \frac{1}{\beta } = 2\), and ρ denotes an arbitrary state.

The proof is analogous to the proof of Eqs. (24) and (25). The forward and reverse POVMs are replaced with POVMs I and II. One can prove analogous uncertainty relations in which Kirkwood-Dirac quasiprobabilities replace Awk. The weak measurement of A gives way to a weak measurement of an A eigenprojector. The uncertainty bound (40) can be smoothed when (α, β) = (∞, 1/2). For uncertainty relations that involve weak measurements, but are not entropic, see ref. 37.

Let us illustrate the uncertainty relation (40) for (α, β) = (∞, 1/2). The system, denoted by a subscript s, consists of a qubit. So does the detector, denoted by d. Let \({\cal{I}} = \sigma _{\mathrm{s}}^z\), \(A = \sigma _{\mathrm{s}}^y\), and \(F = \sigma _{\mathrm{s}}^x\).

The weak measurement manifests as follows: The detector begins in the state |x+〉, a z-controlled y couples the system to the detector weakly, and the detector’s \(\sigma _{\mathrm{d}}^y\) is measured strongly. The weak values Awk(zs, xs) = xszsi are imaginary and so nonclassical36: A has only real eigenvalues a, but the conditioned average Awk is imaginary.

We illustrate the uncertainty relation’s LHS with ρ = |z+〉〈z+|. The inequality is calculated in Supplementary Note 5: \(2.00 \ge 2.00 - \frac{2}{{{\mathrm{ln}}2}}|\tilde g| + O\left( {\tilde g^2} \right)\). If \(\tilde g = 2.00\, \times \,10^{ - 2}\), as in the Methods section, the relation approximates to 2.00 ≥ 1.94. The bound is satisfied and is tight at order g0.

Discussion

We have reconciled two measures of disagreement between quantum operators: entropic uncertainty relations and out-of-time-ordered correlators (OTOCs). The reconciliation unites several subfields of physics: (i) quasiprobabilities and weak measurements tie (ii) quantum information theory to (iii) condensed-matter and (iv) high-energy physics. Information theory and complexity theory have begun intersecting with condensed-matter and high-energy physics recently, shedding light on black holes, information propagation, and space-time. This paper broadens the intersection into quasiprobability and quantum-measurement theory and farther into quantum information theory.

This broadening has two more important significances: one for OTOC theory and one for weak-measurement theory. First, the extension reconciles the OTOC’s V with the tiny perturbation that triggers violent consequences in the classical butterfly effect: V can naturally be regarded, our uncertainty relations show, as being measured weakly. The weak measurement is perturbative literally, in the coupling strength g.

Within measurement theory, second, we have uncovered a physical significance of weak values Awk and Kirkwood-Dirac quasiprobabilities: These quantities govern first-order terms in entropic uncertainty relations obeyed by weak measurements. Quantum information theory therefore sheds light on mathematical objects whose interpretations have been debated in quantum optics, quantum foundations, and quantum computation.

In a recent paper, an uncertainty relation was extended to unitaries, then applied to bound the OTOC38. OTOC bounds have been known to limit the speed at which many-body entanglement can develop22,39,40. The present work takes a fundamentally different approach: Scrambling takes central stage in this paper, whose main purpose is to unite two communities’ notions of quantum operator disagreement. Additionally, our uncertainty relations are entropic, tapping into recent developments in pure quantum information theory. Finally, our formalism covers both unitary and Hermitian OTOC operators V and W.

This work uncovers several research opportunities. Inspired by condensed-matter, we have focused on discrete systems. Also continuous systems—quantum field theories (QFTs)—have OTOCs used to study, e.g., black holes in the anti-de-Sitter-space/conformal-field-theory (AdS/CFT) duality2. Entropic uncertainty relations for continuous-variable systems have been derived (e.g., ref. 41). They should be applied to characterize scrambling in QFTs.

Second, our entropic uncertainty relations [Eqs. (24), (25), (39), and (40)] can be tested experimentally. The techniques needed exist: OTOC measurements have been proposed in detail (e.g., refs. 5,6,24,42,43,44,45,46), and early-stage OTOC-measurement experiments have performed47,48,49,50; weak values and Kirkwood-Dirac distributions have been measured weakly (e.g., refs. 51,52,53,54,55,56,57); and entropic uncertainty relations have been tested experimentally (e.g., refs. 58,59,60,61). Testing Eqs. (24) and (25) should be feasible in the immediate future, especially through the weak-measurement proposal for inferring the OTOC quasiprobability5,24 \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_\rho\). Prospective platforms include superconducting qubits, ultracold atoms, trapped ions, quantum dots, and potentially NMR.

Testing Eqs. (39) and (40) experimentally requires even fewer resources: Interacting many-body systems are unnecessary, and one weak measurement per trial suffices. Tantalizingly, though, two62,63,64 and three65 sequential weak measurements have been realized recently. They can be applied to (i) characterize higher-order terms in Eqs. (40) and (41), (ii) test entropic uncertainty relations for higher-point OTOCs, and (iii) test entropic uncertainty relations for POVMs of sequential weak measurements.

Third, the entropic uncertainty relations for scrambling can be smoothed with an error tolerance ε. When smoothing, one ignores highly unlikely events32. Highly unlikely outcomes of weak-measurement experiments correspond to anomalous weak values and nonclassical quasiprobability values66. Nonclassical operator disagreement underlies nontrivial uncertainty relations. Whether smoothing trivializes entropic uncertainty relations for weak measurements merits study. Rough numerical studies suggest that ε might actually tighten the spin-chain bound (25).

Like smoothing, conditioning generalizes the entropic uncertainty relations in ref. 28. Consider holding a memory σ that is entangled with a to-be-measured state ρ. Conditioning on σ can change your uncertainty about the measurement outcome. Certain scrambling set-ups might be cast in terms of a memory σ. An example consists of a qubit chain and an ancilla qubit67. Consider entangling the ancilla with the chain’s central qubit, then evolving the chain under a many-body Hamiltonian. The entanglement with the ancilla spreads through the chain. The ancilla might be cast as the memory σ in conditioned entropic uncertainty relations for scrambling.

Finally, nonclassicality of \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{ \mathbb{1} }\) and Awk might strengthen the uncertainty bounds. The quasiprobability behaves nonclassically by acquiring negative real and nonzero imaginary components. The weak value Awk behaves nonclassically by lying outside the spectrum of A. Such nonclassical mathematical behavior can signal nonclassical physics26. The quasiprobability’s nonclassicality features little in our numerical example (in the Methods section): First, the quasiprobability’s imaginary part vanishes when evaluated on \({\mathbb{1}}\) (ref. 5, Sec. III and Sec. V A). Hence, \({\rm{Im}} ( \tilde{ {\mathscr{A}}_{\mathbb{1}}})\) cannot influence the bound. Second, \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{{1} }\) assumes negative values, but not when w1 = w2. Higher-point-OTOC quasiprobabilities could avoid this roadblock, and assume negative values in the bound, as higher-point forward and reverse protocols depend on weak W(t) measurements. See the Extension to higher-point OTOCs subsection of the Results. Nonclassicality’s potential to tighten uncertainty bounds merits study.

Methods

We illustrate the entropic uncertainty relations for quantum information scrambling [Eqs. (24) and (25)] with an interacting spin chain. The set-up and weak-measurement implementation are described first. The detector probabilities \(p^V_{j_\ell}\), the weak-measurement Kraus operators \(K^{V, v_\ell}_{j_\ell}\), the couplings \(j_\ell\), and the entropies Hα are presented next, as well as calculated in Supplementary Note 3. Results are presented and analyzed last.

Spin-chain set-up

Consider a one-dimensional (1D) chain of N = 8 qubits. The OTOC operators manifest as single-qubit Pauli operators: \(V = \sigma _1^z\), and \(W = \sigma _N^z\). The operators’ precise forms do not impact our chaotic-system results, however.

Model: The chain evolves under the power-law quantum Ising Hamiltonian68

Each spin j interacts with each spin that lies within a distance \(\ell _0\). The interaction strength declines with distance as a power-law controlled by ζ > 0. We choose J = 1, ζ = 6, and \(\ell _0 = 5\), as in ref. 68. Planck’s constant is set to one: ħ = 1. We set the transverse field hx to 1.05. The longitudinal field \(h_j^z = 0.375( - 1)^j\) flips from site to site.

The transverse-field Ising model with a longitudinal field reproduces our results’ qualitative features. However, the power-law quantum Ising model mimics all-to-all interactions, such as in the SYK model17,18,19,20. Around t = t*, therefore, the OTOC decays almost exponentially. Exponential decay evokes classical chaos, as discussed in the introduction.

Weak-measurement implementation: The Analysis subsection of the Results guides our implementation, which parallels ref. 9. We illustrate with the forward-protocol weak measurement, temporarily reinstating operators’ hats.

The detector consists of a particle that scatters off the system. The detector could manifest as a photon, as in circuit QED69 and in purely photonic experiments51. Let \({\hat{\mathrm{y}}}_{}^{}\) denote the longitudinal direction, which points from the detector’s initial position to the system.

Let \({\hat{\mathrm{x}}}_{}^{}\) denote a transversal direction; and |D〉, the \({\hat{\mathrm{x}}}_{}^{}\) component of the detector’s initial state. |D〉 consists of a Gaussian,

centered on the transverse-momentum eigenvalue p ≡ px = 0. Δ denotes the Gaussian’s standard deviation.

The displaced detector position \(\hat x - x_0\hat{\mathbb{1}}\) couples to the system’s \(\hat \Pi _{v_\ell }^{\hat V}\). \(\left[ {\hat \Pi _{v_\ell }^{\hat V}} \right.\) can effectively be measured weakly via coupling of the detector to \(V = \hat \sigma _\ell ^z\). The interaction unitary will have the form \({\mathrm{exp}}\left( { - \frac{i}{\hbar }\tilde g\left[ {\hat x \otimes \hat \sigma _\ell ^z} \right]} \right)\). The Pauli operator decomposes as \(\hat \sigma _\ell ^z = \pm \left( {2\hat \Pi _ \pm ^{\hat V} - \hat{\mathbb{1}}} \right)\). Hence, the interaction unitary has the form \({\mathrm{exp}}\left( { \pm \frac{i}{\hbar }\tilde g\left[ {\hat x \otimes \hat{\mathbb{1}}} \right]} \right){\mathrm{exp}}\left( { \mp \frac{{2i}}{\hbar }\tilde g\left[ {\hat x \otimes \hat \Pi _ \pm ^{\hat V}} \right]} \right).\) The Kraus operator becomes \(\left\langle {x_\ell } \right|{\mathrm{exp}}\left( { \pm \frac{i}{\hbar }\tilde g\left[ {\hat x \otimes \hat{\mathbb{1}}} \right]} \right){\mathrm{exp}}\left( { \mp \frac{{2i}}{\hbar }\tilde g\left[ {\hat x \otimes \hat \Pi _ \pm ^{\hat V}} \right]} \right)\left| D \right\rangle\). The left-hand exponential can be absorbed into the strong measurement of the detector: Consider wishing to measure \(\hat \Pi _ + ^{\hat V}\) weakly. Instead of measuring the detector’s \(\left\{ {|x_\ell \rangle } \right\}\) strongly, one measures \(\left.\left\{ {e^{ - \frac{i}{\hbar }\tilde g\hat x}|x_\ell \rangle } \right\}. \right]\) [The displacement prevents the minimization in Eq. (26) from choosing the detector-measurement outcome x = 0. This choice would set \(g_{x_\ell }^V\) to \(g_{x_\ell }^V = 0\), eliminating the weak measurement.] The interaction unitary has the form

The interaction strength \(\tilde g_{}^{}\) governs the outcome-dependent coupling \(g_{j_\ell }^{\hat V}\). Numerical experiments show that \(\tilde g = 0.02\) and x0 = 10 keep \(\frac{{g_{j_\ell }^V}}{{\sqrt {p_{x_\ell }^V} }}\) perturbatively small while strengthening the bound.

The detector’s \(\hat x\) is measured strongly. Let L > 0 denote the measurement’s precision. Positions x1 and x2 can be distinguished if they lie a distance |x2 − x1| ≥ L apart. Hence, the classical register has a discrete spectrum \(\{ x_\ell \}\). We simulated a register whose L = 0.1.

Analytical ingredients in spin-chain uncertainty relation

Analytical results are presented here: the detector probability \(p_{j_\ell }^{\hat V} \equiv p_{x_\ell }^{\hat V}\), the weak-measurement Kraus operators \(\hat K_{j_\ell }^{\hat V,v_\ell } \equiv \hat K_{x_\ell }^{\hat V,v_\ell }\), the coupling strengths \(g_{j_\ell }^{\hat V} \equiv g_{x_\ell }^{\hat V}\), and the entropies Hα. We derive these results and check their practicality in Supplementary Note 3.

Consider preparing the detector in |D〉, then measuring \(\hat x_{}^{}\). The measurement has a probability \(p_{x_\ell }^{\hat V}L = |\langle x_\ell |D\rangle |^2L\) of yielding a position within L of \(x_\ell\). By Eq. (43),

The weak-measurement Kraus operators have the form

The outcome-dependent coupling is

The Rényi-α entropy limits, as α → ∞, to

The other entropies have analogous forms.

Entropies Hα: Let us remove operators’ hats. We illustrate the entropies’ analytical forms with

The measurement operators have the form

by Eq. (13). We substitute in from Eq. (12), multiply out, and substitute into Eq. (51):

The other entropies have analogous forms.

Spin-chain results

Figures 1–3 illustrate the entropic uncertainty relations for information scrambling [Eqs. (24) and (25)] in the characteristic parameter regime detailed in the Analytical ingredients above. Time is measured in units of the inverse coupling, 1/J = 1. The scrambling time t* ≈ 4, as reflected by (i) the quasiprobability’s sharp change in Fig. 2 and (ii) the OTOC’s decay in omitted plots.

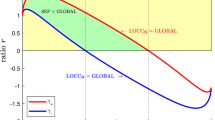

Greatest coupling-dependent contributions to the bound: We numerically simulated a one-dimensional chain of N = 8 qubits evolving under the power-law quantum Ising Hamiltonian (42). The nearest-neighbor coupling J = 1, the transverse field hx = 1.05, and ζ = 6 and \(\ell _0 = 5\) govern the interactions’ power-law decay. The system was initialized in the Gibbs state ρ = e−βH/Z at inverse temperature β = 1. The weak-coupling strength \(\tilde g = 0.02\). The out-of-time-ordered-correlator (OTOC) operators V and W manifest as single-qubit Pauli operators localized on opposite sides of the chain: \(V = \sigma _1^z\), and \(W = \sigma _N^z\). The greatest coupling-dependent contributions to the entropic uncertainty bound f(v1 = 1, v2 = −1) [Eq. (26)] are plotted against time, measured in units of 1/J. The bound tightens at the scrambling time t ≈ t*. This growth confirms that Eqs. (24–26) unify two notions of operator disagreement, entropic uncertainty relations and information scrambling.

Quasiprobability’s contribution to the bound: The quasiprobability \(\tilde {\mathscr{A}}_{\mathbb{1}}\) governs three terms in the entropic uncertainty bound for scrambling, f(v1 = 1, v2 = −1) [Eq. (26)]; these terms are plotted against time. We numerically simulated a one-dimensional chain of N = 8 qubits evolving under the power-law quantum Ising Hamiltonian (42). The nearest-neighbor coupling J = 1, the transverse field hx = 1.05, and ζ = 6 and \(\ell _0 = 5\) govern the interactions’ power-law decay. The system was initialized in the Gibbs state ρ = e−βH/Z at inverse temperature β = 1. The weak-coupling strength \(\tilde g = 0.02\). The out-of-time-ordered-correlator (OTOC) operators \(V = \sigma _1^z\) and \(W = \sigma _N^z\).

Left-hand and right-hand sides: Two entropic uncertainty relations for information scrambling are presented. The orange, dashed curve illustrates the HvN + HvN of Eq. (24). The blue, dash-dotted curve illustrates the Hmin + Hmax of Eq. (25) for (α, β) = (∞, 1/2). The green, solid curve of Eq. (26) illustrates the bound f(v1 = 1, v2 = −1). The bound’s tightening is undetectable due to the y-axis scale. We numerically simulated a one-dimensional chain of N = 8 qubits evolving under the power-law quantum Ising Hamiltonian (42). The nearest-neighbor coupling J = 1, the transverse field hx = 1.05, and ζ = 6 and \(\ell _0 = 5\) govern the interactions’ power-law decay. The system was initialized in the Gibbs state ρ = e−βH/Z at inverse temperature β = 1. The weak-coupling strength \(\tilde g = 0.02\). The out-of-time-ordered-correlator (OTOC) operators \(V = \sigma _1^z\) and \(W = \sigma _N^z\).

Figure 1 shows the greatest time-dependent contributions to the bound f(v1,v2) [Eq. (26)]. Choosing v1 = −v2 tightens the bound (see Supplementary Note 2), so we focus on v1 = 1 and v2 = −1. The bound grows at t = t*, confirming expectations: at the scrambling time, the OTOC drops. A decayed OTOC reflects noncommutation of V and W(t). The worse two operators commute, the stronger their entropic uncertainty relations; the stronger the uncertainty bound f(v1, v2). Hence, Eqs. (24) and (25) unite information scrambling and OTOCs with entropic uncertainty relations, as claimed.

Figure 2 shows the quasiprobability’s contribution to the uncertainty bound (26). Figure 3 shows the LHS of Eq. (24) (HvN + HvN), the LHS of Eq. (25) at (α, β) = (∞, 1/2) (Hmin + Hmax), and the shared RHS f(v1, v2). Figure 3 is more zoomed-out than Fig. 2; hence the tightening is too small to detect. This reduced visibility is expected: scrambling is a subtle, high-order stage of quantum equilibration. It manifests in the g2 terms of f(v1, v2), just as \(\tilde{{\mathscr{A}}_\rho }\) can be inferred from high-order terms in weak-measurement experiments5,24.

The LHSs lie ~10 bits above the bound. The gap stems from the Tr(\(\Pi^W_{w_2}\)) = 2N−1 in Eq. (26). This gap bodes ill for the large-system limit, N → ∞, of interest in holography. However, the gap scales only linearly, not exponentially, with N. Furthermore, small gaps would follow from many of today’s experiments (e.g., ref. 47). Additionally, the Entropic uncertainty relations for weak values beyond scrambling subsection presents weak-measurement entropic uncertainty relations independent of scrambling. Those uncertainty relations need not have such a gap. We illustrate with a qubit example whose bound is tight at zeroth order in g, in the subsection Entropic uncertainty relations for weak values beyond scrambling.

Figure 4 illustrates how tight the bound can grow in an exceptional parameter regime. The top curves represent Hmin + Hmax and HvN + HvN. These curves dip at t ≈ t* because (i) ρ is a W(t ≈ t*) eigenstate and (ii) the POVMs’ W(t) measurements are fine-grained—are replaced with measurements of \(\left\{ {U^\dagger |w_\ell ,\alpha_{w_\ell} \rangle} \right\}\). The POVM outcomes become highly predictable around t*, so the bound grows tight to within 0.53 bits. In addition to choosing ρ and to fine-graining, we raised the interaction strength to \(\tilde g = 0.16\). The outcome-dependent coupling strengths \(g_{x_\ell }^V\) are comparable to the detector probabilities: \(g_{x_\ell }^V \approx p_{x_\ell }^V\). This comparability invalidates the Taylor expansion that leads to Eq. (26). Equation (15) in Supplementary Note 1 gives the pre-Taylor-expansion bound. This bound appears as the solid, green, bottom curve in Fig. 4. The bound would rise more than in the earlier figures, if the POVMs’ W(t) measurements remained fine-grained: The large g’s would magnify the \(\tilde{\mathscr{ A}}_{\mathbb{1}}\) term’s rise. Since the W(t) measurements are fine-grained, the POVMs cease to capture the spirit of scrambling, defined in terms of local V and W. Hence, we should not necessarily expect scrambling to lift the bound.

Strengthened bound in exceptional parameter regime: We numerically simulated a one-dimensional chain of N = 8 qubits evolving under the power-law quantum Ising Hamiltonian (42). The initial state ρ is a W(t) eigenstate, wherein the time t is evaluated at the scrambling time t*. The out-of-time-ordered-correlator (OTOC) operator \(V = \sigma _1^z\). The W(t) measurements in the positive-operator-valued measures (13 and 14) are fine-grained [are measurements of a \(W(t) = \sigma _N^z\) eigenbasis, rather than measurements of W(t)]. The nearest-neighbor coupling J = 1, the transverse field hx = 1.05, and ζ = 6 and \(\ell _0 = 5\) govern the interactions’ power-law decay. The interaction strength \(\tilde g = 0.16\), rendering the measurement-dependent coupling strengths \(g^V_{x_1, x_2}\) comparable to the detector probabilities \(p^V_{x_1, x_2}\). This comparability invalidates the Taylor expansion that leads to (26). The bound (26) appears as the green, solid curve. The orange, dashed curve illustrates HvN + HvN [Eq. (24)]. The blue, dash-dotted curve illustrates Hmin + Hmax [Eq. (25) at (α, β) = (∞, 1/2)]. The upper curves drop to within 0.53 bits of the bound (the green, solid curve).

Our numerics emphasize the scrambling Hamiltonian HPQIM, which is nonintegrable. Integrable Hamiltonians’ OTOCs revive and decay repeatedly, as information recollects from across the system and spreads again. The revivals and decays lift and suppress f(v1,v2), we have confirmed using a transverse-field Ising model. The relevant plots are omitted but appear at Simulation code and data https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7700072.v1.

Data availability

The simulation data and code are available at (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7700072.v1).

References

Coles, P. J., Berta, M., Tomamichel, M. & Wehner, S. Entropic uncertainty relations and their applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 015002 (2017).

Swingle, B. Unscrambling the physics of out-of-time-order correlators. Nat. Phys. 14, 988–990 (2018).

Roberts, D. A. & Yoshida, B. Chaos and complexity by design. J. High. Energy Phys. 2017, 121 (2017).

Haehl, F. M., Loganayagam, R., Narayan, P. & Rangamani, M. Classification of out-of-time-order correlators. Sci. Post Phys. 6, 001 (2019).

Yunger Halpern, N., Swingle, B. & Dressel, J. Quasiprobability behind the out-of-time-ordered correlator. Phys. Rev. A 97, 042105 (2018).

Dressel, J., González Alonso, J. R., Waegell, M. & Yunger Halpern, N. Strengthening weak measurements of qubit out-of-time-order correlators. Phys. Rev. A 98, 012132 (2018).

Haehl, F. M. & Rozali, M. Fine grained chaos in ads2 gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 121601 (2018).

Tamir, B. & Cohen, E. Introduction to weak measurements and weak values. Quanta 2, 7–17 (2013).

Aharonov, Y., Albert, D. Z. & Vaidman, L. How the result of a measurement of a component of the spin of a spin-1/2 particle can turn out to be 100. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 1351–1354 (1988).

Heisenberg, W. Über den anschaulichen inhalt der quantentheoretischen kinematik und mechanik. Z. f.ür. Phys. 43, 172–198 (1927).

Kennard, E. H. Zur quantenmechanik einfacher bewegungstypen. Z. f.ür. Phys. 44, 326–352 (1927).

Robertson, H. P. The uncertainty principle. Phys. Rev. 34, 163–164 (1929).

Deutsch, D. Uncertainty in quantum measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 50, 631–633 (1983).

Tomamichel, M. Quantum Information Processing with Finite Resources—Mathematical Foundations (Springer, 2016). https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319218908.

Wilde, M. M. Quantum Information Theory 2nd edn (Cambridge University Press, 2017). https://www.cambridge.org/us/academic/subjects/computer-science/cryptography-cryptology-and-coding/quantum-information-theory-2nd-edition?format=HB&isbn=9781107176164

Maassen, H. & Uffink, J. B. M. Generalized entropic uncertainty relations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 1103–1106 (1988).

Sachdev, S. & Ye, J. Gapless spin-fluid ground state in a random quantum heisenberg magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 3339–3342 (1993).

Kitaev, A. A Simple Model of Quantum Holography. KITP strings seminar and Entanglement 2015 program (2015). http://online.kitp.ucsb.edu/online/entangled15/kitaev/, http://online.kitp.ucsb.edu/online/entangled15/kitaev2/.

Polchinski, J. & Rosenhaus, V. The spectrum in the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev model. J. High. Energy Phys. 4, 1 (2016).

Maldacena, J. & Stanford, D. Remarks on the sachdev-ye-kitaev model. Phys. Rev. D. 94, 106002 (2016).

Brown, W. & Fawzi, O. Scrambling speed of random quantum circuits. ArXiv e-prints (2012).

Lashkari, N., Stanford, D., Hastings, M., Osborne, T. & Hayden, P. Towards the fast scrambling conjecture. J. High. Energy Phys. 2013, 22 (2013).

Hosur, P., Qi, X. -L., Roberts, D. A. & Yoshida, B. Chaos in quantum channels. J. High. Energy Phys. 2, 4 (2016).

Yunger Halpern, N. Jarzynski-like equality for the out-of-time-ordered correlator. Phys. Rev. A 95, 012120 (2017).

González Alonso, J. R., Yunger Halpern, N. & Dressel, J. Out-of-time-ordered-correlator quasiprobabilities robustly witness scrambling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 040404 (2019).

Spekkens, R. W. Negativity and contextuality are equivalent notions of nonclassicality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 020401 (2008).

Arvidsson-Shukur, D. R. M. et al. Contextuality provides quantum advantage in postselected metrology. arXiv e-prints arXiv:1903.02563 (2019). 1903.02563.

Tomamichel, M. A Framework for Non-Asymptotic Quantum Information Theory. Ph.D. thesis, ETH Zürich (2012).

Krishna, M. & Parthasarathy, K. An entropic uncertainty principle for quantum measurements. eprint arXiv:quant-ph/0110025 (2001). quant-ph/0110025.

Preskill, J. in Quantum Computation Lecture notes (2015).

Bhatia, R. Matrix Analysis. (Springer, New York, 1997).

Renner, R. Security of Quantum Key Distribution. Ph.D. thesis, ETH Zürich (2005).

Rastegin, A. E. Uncertainty relations for arbitrary measurement in terms of Renyi entropies. ArXiv e-prints (2008). 0805.1777.

Shenker, S. H. & Stanford, D. Black holes and the butterfly effect. J. High. Energy Phys. 3, 67 (2014).

Roberts, D. A. & Swingle, B. Lieb-robinson bound and the butterfly effect in quantum field theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 091602 (2016).

Dressel, J. & Jordan, A. N. Significance of the imaginary part of the weak value. Phys. Rev. A 85, 012107 (2012).

Hall, M. J. W., Pati, A. K. & Wu, J. Products of weak values: uncertainty relations, complementarity, and incompatibility. Phys. Rev. A 93, 052118 (2016).

Bong, K. -W. et al. Strong unitary and overlap uncertainty relations: theory and experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 230402 (2018).

Maldacena, J., Shenker, S. H. & Stanford, D. A bound on chaos. JHEP 08, 106 (2016).

Sekino, Y. & Susskind, L. Fast scramblers. J. High. Energy Phys. 2008, 065 (2008).

Bialynicki-Birula, I. Formulation of the uncertainty relations in terms of the rényi entropies. Phys. Rev. A 74, 052101 (2006).

Swingle, B., Bentsen, G., Schleier-Smith, M. & Hayden, P. Measuring the scrambling of quantum information. Phys. Rev. A 94, 040302 (2016).

Yao, N. Y. et al. Interferometric approach to probing fast scrambling. ArXiv e-prints (2016). 1607.01801.

Zhu, G., Hafezi, M. & Grover, T. Measurement of many-body chaos using a quantum clock. Phys. Rev. A94, 062329 (2016).

Bohrdt, A., Mendl, C. B., Endres, M. & Knap, M. Scrambling and thermalization in a diffusive quantum many-body system. New J. Phys. 19, 063001 (2017).

Tsuji, N., Shitara, T. & Ueda, M. Out-of-time-order fluctuation-dissipation theorem. Phys. Rev. E 97, 012101 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Measuring out-of-time-order correlators on a nuclear magnetic resonance quantum simulator. Phys. Rev. X 7, 031011 (2017).

Gärttner, M. et al. Measuring out-of-time-order correlations and multiple quantum spectra in a trappedion quantum magnet. Nat. Phys. 13, 781 (2017).

Wei, K. X., Ramanathan, C. & Cappellaro, P. Exploring localization in nuclear spin chains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 070501 (2018).

Meier, E. J., Ang’ong’a, J., An, F. A. & Gadway, B. Exploring quantum signatures of chaos on a Floquet synthetic lattice. ArXiv e-prints (2017). 1705.06714.

Lundeen, J. S., Sutherland, B., Patel, A., Stewart, C. & Bamber, C. Direct measurement of the quantum wavefunction. Nature 474, 188–191 (2011).

Ritchie, N. W. M., Story, J. G. & Hulet, R. G. Realization of a measurement of a weak value. Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 1107–1110 (1991).

Bollen, V., Sua, Y. M. & Lee, K. F. Direct measurement of the kirkwood-rihaczek distribution for the spatial properties of a coherent light beam. Phys. Rev. A 81, 063826 (2010).

Lundeen, J. S. & Bamber, C. Procedure for direct measurement of general quantum states using weak measurement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 070402 (2012).

Groen, J. P. et al. Partial-measurement backaction and nonclassical weak values in a superconducting circuit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 090506 (2013).

Bamber, C. & Lundeen, J. S. Observing dirac’s classical phase space analog to the quantum state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 070405 (2014).

Mirhosseini, M., Magaña Loaiza, O. S., Hashemi Rafsanjani, S. M. & Boyd, R. W. Compressive direct measurement of the quantum wave function. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 090402 (2014).

Sulyok, G. et al. Experimental test of entropic noise-disturbance uncertainty relations for spin-1/2 measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 030401 (2015).

Berta, M., Wehner, S. & Wilde, M. M. Entropic uncertainty and measurement reversibility. New J. Phys. 18, 073004 (2016).

Xing, J. et al. Experimental investigation of quantum entropic uncertainty relations for multiple measurements in pure diamond. Sci. Rep. 7, 2563 (2017).

Xiao, L. et al. Experimental test of uncertainty relations for general unitary operators. Opt. Express 25, 17904–17910 (2017).

Piacentini, F. et al. Measuring incompatible observables by exploiting sequential weak values. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 170402 (2016).

Suzuki, Y., Iinuma, M. & Hofmann, H. F. Observation of non-classical correlations in sequential measurements of photon polarization. New J. Phys. 18, 103045 (2016).

Thekkadath, G. S. et al. Direct measurement of the density matrix of a quantum system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 120401 (2016).

Chen, J. -S. et al. Experimental realization of sequential weak measurements of non-commuting Pauli observables. Opt. Express 27, 6089 (2019).

Dressel, J. Weak values as interference phenomena. Phys. Rev. A 91, 032116 (2015).

Swingle, B. Quantum many-body systems and quantum gravity. (Boulder School for Condensed Matter and Materials Physics, 2018). https://boulderschool.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/qi_boulder.pdf.

Swingle, B. & Yunger Halpern, N. Resilience of scrambling measurements. Phys. Rev. A 97, 062113 (2018).

de Lange, G. et al. Reversing quantum trajectories with analog feedback. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 080501 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for conversations with Fernando G. S. L. Brandão, Sean Carroll, Justin Dressel, Patrick Hayden, José Raúl Gonzalez Alonso, Renato Renner, Brian Swingle, and Marco Tomamichel. N.Y.H. is grateful for support from the Institute for Quantum Information and Matter (IQIM), for a Barbara Groce Graduate Fellowship, and for a Graduate Fellowship from the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics. N.Y.H. acknowledges Mark van Raamsdonk, his fellow conference organizers, the It from Qubit collaboration, and UBC for their hospitality and their invitation to participate in Quantum Information in Quantum Gravity III, where this project partially took shape. A.B. acknowledges support from the Walter Burke Institute for Theoretical Physics and the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of High Energy Physics, under Award Number DE-SC0011632. J.P. is supported partially by the Simons Foundation and partially by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. The IQIM is an NSF Physics Frontiers Center (NSF Grant PHY-1125565) that receives support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (GBMF-2644). The KITP is supported by the NSF under Grant No. NSF PHY-1125915.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this paper equally.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yunger Halpern, N., Bartolotta, A. & Pollack, J. Entropic uncertainty relations for quantum information scrambling. Commun Phys 2, 92 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0179-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0179-8

This article is cited by

-

Uncertainty from the Aharonov–Vaidman identity

Quantum Studies: Mathematics and Foundations (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.