Abstract

The emergence of a fractal energy spectrum is the quintessence of the interplay between two periodic parameters with incommensurate length scales. crystals can emulate such interplay and also exhibit a topological bulk-boundary correspondence, enabled by their nontrivial topology in virtual dimensions. Here we propose, fabricate and experimentally test a reconfigurable one-dimensional (1D) acoustic array, in which the resonant frequencies of each element can be independently fine-tuned by a piston. We map experimentally the full Hofstadter butterfly spectrum by measuring the acoustic density of states distributed over frequency while varying the long-range order of the array. Furthermore, by adiabatically changing the phason of the array, we map topologically protected fractal boundary states, which are shown to be pumped from one edge to the other. This reconfigurable crystal serves as a model for future extensions to electronics, photonics and mechanics, as well as to quasi-crystalline systems in higher dimensions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The almost Mathieu operator \(H_{\phi ,\theta } = T + T^\dagger + \lambda \,\cos (2\pi \phi X + \theta )\) was introduced by Peierls in 19331, in his study of electron dynamics under magnetic fields. It acts on a 1D lattice, where T and X are the translation and position operators, respectively. When λ = 2, the operator connects to Harper's equation2, which expresses the 2-dimensional (2D) magnetic Schrödinger operator in the Landau gauge, with ϕ representing the magnetic flux through the primitive cell. Ever since the work of Hofstadter from 19763, material scientists are well aware of the spectral properties of this operator, which were further investigated with semianalytical methods by Aubry and Andre4, and with rigorous methods by many mathematical physicists5,6. It is known, for example, that for all irrational values of ϕ, the spectrum is a Cantor set whose size measures to \(\left| {{\mathrm{Spec}}\left( H \right)} \right| = |4 - 2\lambda |\). Furthermore, for λ > 2, the eigenmodes are localized in space with exponentially decaying profiles, while the eigenmodes are extended for λ > 2. At the transition point λ = 2, the spectrum is fractal and its measure vanishes, hence it consists mostly of gaps. As we shall see, all these gaps are topological in the sense that they all support nontrivial bulk-boundary correspondences, a statement that actually remains valid even when the potential and the couplings are replaced by generic quasiperiodic functions7.

Fractal spectra encode interesting patterns of self-similarity, and large efforts have been devoted to their experimental observation. Several groups have proposed indirect methods to chase the butterfly spectrum, for example, by measuring quantization Hall conductance in magnetotransport8,9 or by using ultra cold atoms as a tool of mapping Haper Hamiltonian10,11,12 to obtain evidence of fractal spectrum. The first realization of a butterfly spectrum was carried out by measuring microwave as well as acoustic transmittance through an array of scatterers13,14. Years later, several groups independently reported evidence of butterfly spectra by investigating the electronic behavior of graphene super-lattices under the modulation of long-range periodic potential and magnetic field perpendicular to graphene superlattices15,16,17, and fractal magnetic Bloch states were revealed18. A more recent work used nine superconducting qubits as a tool to demonstrate the spectroscopic signature of this energy spectrum19.

In Harper’s equation, the parameter θ represents the electron quasimomentum in a chosen direction. As such, by varying θ over the full interval [0, 2π], one essentially recovers the physics of electrons on a 2D lattice subjected to a perpendicular magnetic field20. These quantum systems display the Integer Quantum Hall Effect (IQHE), hence it is not difficult to understand why the almost Mathieu operator possess a nontrivial bulk-boundary correspondence. Nevertheless, the possibility of implementing the operator with quasiperiodic 1D platforms opens up new ways to observe and study the associated topological phenomena. A number of theoretical and experimental works have recently induced quasiperiodicity in a broad variety of systems7,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 to explore topological phase transitions and edge states. Even more, topological phases in higher dimensions23,28,29,30,31 have been predicted and the those characterized by second class Chern number in 2D quasiperiodic crystals observed experimentally21,22.

Despite all these advances, reconfigurable experimental platforms were missing to construct the exact quasiperiodic lattice and to emulate the topological effects, yet they are much needed for a thorough exploration of their physics, such as the observation of the Hofstadter butterfly spectrum or pumping the edge states from one boundary to the other. In this paper, we present our design and 3D-printed realization of a reconfigurable 1D acoustic metamaterial, made of resonators with tunable onsite frequency. The reconfigurable design allows us to construct arbitrary phason configurations of the quasiperiodic array, thus, it enables experimentally mapping Hofstadter butterfly spectrum and topological edge states for sound in a straightforward way by simply tuning the piston of resonators. Compared to the previous works which mapped the fractal bulk spectrum in the classical system13,14 through simulating “onsite potential” by a step function, our structure can mimic the variation of the “onsite potential” in Harper/Aubry–André equation in a “sinusoidal” manner. In addition, both adiabatic pumping (mapping edge states spectrum) and nonadiabatic pumping (mapping Hofstadter butterfly spectrum) can be easily emulated in our reconfigurable acoustic platform, which are very hard to achieve in the solid states of matter.

Results

Reconfigurable acoustic metamaterial design

The array consists of tunable acoustic resonators connected via circular channels, called bridges hereafter. The height of each resonator can be adjusted by rotating a piston inserted inside a thread, which is printed both on the inner side of the resonator and on the surface of the piston itself. The reconfigurable resonators are shown in Fig. 1a, and the geometry of the structure was optimized to observe the acoustic spectrum with high resolution (see Methods). For example, in order to realize high and stable quality factors for the resonant modes (~50), the unperturbed height of the resonators is chosen as h0 = 40 mm and the modulation depth as \(\delta h_0 = 0.12h_0\). The diameter of the connecting bridges affects the size of the fractal gaps in the butterfly spectrum, therefore an effort was put into optimizing the diameter value to maximize the size of these gaps. The details of the structure optimization can be found in Supplementary Note 1.

1D tunable acoustic quasicrystal. a Schematics of a single resonator with a piston. b Photograph of 8 (out of 37) tunable resonators of the fabricated quasiperiodic acoustic crystal. The maximum height of a single cylinder in Fig. 1a is chosen as \(h_t = h_0 + \delta h_0\), where h0 = 40 mm is the unperturbed height, \(\delta h_0 = 0.12h_0\) is the modulation depth, and variable δh is modulated by the sinusoidal function in the range of \([ - \delta h_0,\delta h_0]\). The diameter of cylinder d0 = 20 mm. The connectors between the cylinders have a diameter dc = 10 mm, with a vertical distance to the bottom of the hollow chamber hc = 5.2 mm

The first-order acoustic pressure mode of the single resonator oscillating in the axial direction of the cylinder (~4.5 kHz) (shown in Supplementary Fig. 1c), with one node at the center of the cavity, is one of the interests for our experiment. The coupling bridges are placed at the bottom of the resonators to minimize the effect on the coupling strength κ of the varying height through the pistons at the top. As long as the modulation depth of height δh is not very large, this assumption holds well, as experimentally confirmed by testing the frequency response of two-coupled resonators (for details see S.M. Section. II). Therefore, if \(\left| {\frac{{\delta h}}{{h_0}}} \right| \ll 1\), and the variation of the resonators’ height follows the modulation protocol \(h_n = h_0 + \delta h\sin \left( {2\pi n\phi + \theta } \right)\), where n is the site index of the resonators, the recursive equations describing an infinite chain of coupled resonators assume the form

where \(\omega _0 \cong \frac{{\pi c}}{{h_0}}\) is the resonator unperturbed onsite angular frequency, c is the speed of sound, \(\gamma \cong \frac{{\delta h}}{{h_0}}\omega _0\), and φn is the amplitude of the collective resonant mode at site n. The parameter θ is a phase factor often referred to as phason. The value of the coupling constant κ is determined by the position and the diameter of the connecting bridges and it can be adjusted by moving the bridges up or down as well as by varying their diameter. The numerical value of κ was experimentally determined from the hybridization of the modes in a dimer configuration (Supplementary Note 2), and the position and geometry of the bridges was adjusted until κ = γ/2, hence tuning the system at the transition λ = 2, where the spectrum is mostly composed of gaps.

Bulk-boundary correspondence

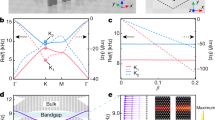

We can encode the data of the collective mode in the vector \(|\varphi \rangle = \sum_n \varphi _n|n\rangle\), in which case Eq. (1) reduces to the eigensystem problem for the almost Mathieu operator Hϕ,θ. It is known that, if ϕ is irrational, the spectrum of Hϕ,θ is actually independent of θ, but this is not the case if ϕ is rational. Hence it is more convenient and appropriate to work with the reunion of the spectra \({\mathrm{Spec}}\left( \phi \right) = \cup_\theta \, {\mathrm{Spec}}( {H_{\phi ,\theta }} )\), since, as we shall see, the topological gaps occur in Spec(ϕ). For example, the individual spectra Spec(Hϕ,θ) can display additional gaps for which it is not possible to define topological invariants, as shown by the midgap in the Fig. 2a. As subsets of the real axis, Spec (ϕ) are known to depend continuously of ϕ and, as such, by sampling ϕ over rational values we can compute an accurate representation of the spectral butterfly, as shown in Fig. 2b. As one can see, in all cases there is a fractal network of spectral gaps. If ϕ is irrational, then between any pair of such gaps there is an infinite number of additional gaps, hence counting the gaps in an orderly fashion is futile. Nevertheless, each gap can be uniquely labeled32 by the value of the integrated density of states (IDS) inside the gaps, defined as the number of eigenvalues below that gap divided by the length of the system, as the length is taken to infinity. For our context, IDS is known30 to be quantized as

Bulk-boundary correspondence in quasiperiodic crystal. a Bulk and edge state energy spectra numerically calculated from Eq. (1) for (p, q) = (1, 6). b Spec(ϕ) based on Eq. (1) at λ = 2, with ϕ sampled over the rational values p/q, q = 611, p = 0,…, q. c–e Spatial profiles of the resonant modes (picked at 4531 Hz) simulated with COMSOL Multiphysics for the 1D quasiperiodic array. The arrays in c–e have the bridges with different diameters dc, which correspond to the cases of λ > 2, λ = 2 and λ < 2, respectively. For all three cases, the parameters were fixed at \(\phi = \frac{8}{{37}}\) and \(\theta = \frac{\pi }{3}\). The colorbar shows the normalized magnitude of acoustic pressure

Furthermore and very importantly, there is the constraint \(0 \le {\mathrm{IDS}} \le 1\). The integer m is connected to the first Chern number C, a fact that can be seen from Streda’s formula \(\frac{{\partial {\mathrm{IDS}}}}{{\partial \phi }} = C\) (The details of applying this formula in the aperiodic case are presented in ref. 33). Given the constraints on IDS, one can immediately see that \(C \,\ne\, 0\) for all gaps except for two cases, namely for the gaps above and below the spectral butterfly. In other words, every true gap of the butterfly is topological. The Chern numbers are continuous (hence constant) functions of ϕ as long as one navigates inside a spectral gap34, and hence does not cross any spectrum of the butterfly. As such, the Chern number can be evaluated for each gap using rational approximants p/q of ϕ (the analytic form of the Chern number for both irrational and rational ϕ is presented in Supplementary Note 3). e.g., by turning Eq. (2) into the Diophantine equation35,36

where j is the index of the minigap counted from the lowest frequency gap. Alternatively, one can integrate the Berry curvature of the gap projection PG over the magnetic Brillouin zone (detailed in Supplementary Note 3). Both methods lead to the same answers and some of the computed Chern values are shown in Fig. 2b for (p, q) = (1, 6).

As was shown by Hatsugai37, the edge of a halved IQHE system carries a topological invariant whose numerical value coincides with the bulk Chern number. Furthermore, this edge topological invariant counts the difference between the positively and negatively dispersing edge bands38. In our context, this means that, at the edge of a half acoustic quasiperiodic chain, we should observe a number of chiral bands equal to the value of bulk Chern number as θ is varied. This is indeed confirmed by our explicit calculations reported in Fig. 2b. Importantly, the stability of this bulk-boundary correspondence against disorder was established in ref. 30.

Furthermore, we demonstrate in Fig. 2c the spectacular change in the spatial profile of the resonant modes as the system transitions between the localized and de-localized regimes by tuning κ, for example, changing the diameter of the bridges dc. When \(\frac{\kappa }{{f_0}} \,<\, 0.06\) (corresponding to the case λ > 2), the eigenstates are localized and exponentially decay, in the example of dc = 8 mm, the acoustic pressure waves in the array are indeed localized (Fig. 2c). However, when \(\frac{\kappa }{{f_0}} \,> \, 0.06\) (corresponding to the case λ < 2), as shown in Fig. 2e, for dc = 12 mm, the acoustic pressure waves extend at every site along the array. Contrary to what one will expect, based on the fact that topological invariants are usually carried by the extended states, the topological bulk-boundary correspondence is not affected by these qualitative differences. The reason is that the topological bulk Chern number, defined above, involves also the virtual dimension of the phason6.

Observation of the Hofstadter butterfly spectrum

In order to observe the fractal structure of the butterfly spectrum, the number of degrees of freedom of the system has to be large, namely the number of resonators should be sufficient to resolve the fractal features. However, the resonance peaks of the system have finite bandwidth due to unavoidable radiation and material loss (e.g., introduced by holes drilled to probe the system and the resin absorption). In addition, acoustic viscosity also contributes to the loss since the size scale of the resonator is in the centimeter. Therefore, it is impossible to resolve the higher-order minigap as the corresponding peaks overlap with each other if the bands are too close (with the separation less than ~70 Hz). Here we choose a number of cells q = 37, as a compromise between the requirements of high resolution and time needed to take measurement for different configurations of the array, while being aware of the finite Q factor of each resonance that would fundamentally limit the observation of higher-order gaps.

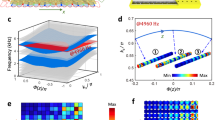

For the first time, we mapped the Hofstadter butterfly through the acoustic density of states (DOS) instead of measuring the acoustic wave transmittance/reflectance for each value of p. We extracted DOS by measuring the frequency responses of each resonator in the quasiperiodic array, in such way the boundary effects on the bulk spectrum can be reduced by excluding DOS of the boundary sites from the spectrum. In the measurement, the speaker is placed at the bottom of each resonator, and the directional microphone is placed at the top of the piston screwed into the same resonator. Both speaker and microphone are placed next to the probe holes, which are intentionally introduced into the geometry as seen in Fig. 1a. The frequency response range from 3600 to 5800 Hz was measured for every resonator, except for the boundary ones. The normalized DOS is obtained through these data (see Methods Section for details). As shown in Fig. 3a, the phason is set as \(\frac{\pi }{3}\), the integer p varies from 1 to q = 37, and its variation changes the spatial periodicity of the sinusoidal function in the array. For example, if p = 8, the sinusoidal wave in the array undergoes eight cycles, and the corresponding measured DOS, shown in Fig. 3b, clearly reveals the main gap m0 in the butterfly spectrum, where the indexing method of Hofstadter’s work is adopted3. The higher-order fractal gaps c−1 in the c−1 region, and one in the r−1 sub-region of the c−1 region are also clearly observed. These results allow us to conclude that at least three orders of fractal gaps in the spectrum can be resolved in our setup.

Measurement of Hofstadter butterfly spectrum. a Schematics of a quasiperiodic lattice with variable long-range order. b Normalized density of states (DOS) for the case p = 8 with fractal bandgaps labeled. c Hofstadter butterfly spectrum mapped from the measured DOS for different p values, the colorbar shows the magnitude of DOS in arbitrary unit. d Peaks of resonance frequencies extracted from the frequency responses for sites 2–36 and for all p values. The red arrow indicates the position p = 8, considered as an example in the text. The axis ϕ = p/q, where q = 37 in the experiment

Normalized DOS for all p values have been measured, and their logarithmic scale amplitude is presented in Fig. 3c, with the brighter part of the spectrum indicating higher DOS in that region. As expected, the spectrum is overall symmetric in the horizontal direction within the range of tolerance due to experimental errors. However, a slight asymmetry present in the vertical direction can be observed, and it is attributed to the fact that the height variation has a minor effect on the hopping strength κ, which has also been verified by our first-principle calculations (shown by red colored dots in Fig. 3d). To better resolve the minigap in the spectrum, the positions of the resonance peaks are extracted from each site for all p values and depicted in blue colored circles in Fig. 3d, and match the simulation results in a precise way. The legality of taking the open boundary in the bulk spectrum measurement comes from several aspects. First of all, frequency responses at boundary sites were not taken into account to generate the butterfly spectrum, therefore, we do not observe many edge states existed inside the bandgaps in the butterfly spectrum (there are few in the lower right main gap of the spectrum). Second, the bulk states, due to the existence of loss in the acoustic structure, cannot propagate over a large distance when they are excited by the source, thus, the effects of boundary conditions on the exited bulk states are lessen because of the reduced propagation length of bulk states.

Pumping topological edge states

To explore the fractal gaps and edge states associated with them in our acoustic quasicrystal, we fix the magnetic flux to ϕ = 1/6. In order to resolve the fractal edge state spectrum, a large number of cells are required. We choose p = 4 and q = 24 in our experimental setup. The field profiles distributed in the arrays shown in Fig. 4a reveals the topological pumping of boundary mode from one side of the array to the other side, as the phason θ varies in the range indicated by red colored lines in Fig. 4b. The phason θ acts similar to a momentum vector, although we present the variation of the arrays in real space. Although the field profiles of the arrays are depicted schematically, they closely reflect the results from first-principle calculations. Only half of the energy spectrum calculated from COMSOL simulations is presented in Fig. 4b due to the spectrum symmetry. Because of the bulk-edge correspondence, one and two gapless edge states are expected in the m0 and c−1 gaps at each boundary.

Mapping the edge spectrum using adiabatic pumping of phason θ for the case (p, q) = (4, 24). a Schematics of edge state transfer during phason θ pumping; the range of this pumping is indicated by the orange line in Fig. 4b. b Band structure obtained from first-principle calculations. c Band spectrum mapped from the measured normalized density of states (DOS) for each θ, the colorbar shows the magnitude of DOS in arbitrary unit. d Acoustic pressure distributions of edge states found from first-principle simulations; these field profiles, from the bottom panel to the top panel, correspond to the edge states marked by dots in Fig. 4b and are arranged from the lower frequency to the higher frequency, the colorbar represents the magnitude of acoustic pressure. e Measured acoustic pressure amplitude distributions Sn in logarithmic scale at different sites of the array from 1 to 24, these field profiles correspond to the edge states marked in dots in Fig. 4c

Compared to the work27, there is no limitation on the number of phason configuration, though we found that taking measurement for 48 phason values is sufficient to clearly resolve the edge spectrum with better resolution than the one in ref. 27. Followed the same procedure as one in measuring butterfly spectrum, the acoustic DOS for each value was obtained. The reconstructed energy spectrum for all phasons is plotted in Fig. 4c, and it is found consistent with our first-principle calculations. One and two edge states are observed in m0 and c−1 gaps, respectively, as indicated by dashed lines in Fig. 4c. When compared to the theoretical results, the crossing of these edge spectra shifts to higher frequency because of the effect of different boundary conditions, specifically, perfectly matched layer boundary conditions are applied in the simulations, while in reality the boundary cells are open to the ambient air environment, which emulates the open boundaries set in the numerical calculation39. However, the edge states emerge irrespective of the boundary conditions, and always retain their gapless and asymmetric character with respect to the phason variation, which vividly demonstrates the robustness of the topological edge states.

The logarithmic scale field profiles of the edge states shown in the Fig. 4d, e confirm their localization at the boundaries both in simulations and in the experimental results, respectively. The edge state profile lines in Fig. 4e are color coded to agree with colors in Fig. 4c. In addition, as can be seen from Fig. 4e, the edge states present in the m0 gap (yellow colored) are found to be more localized than those present in the c−1 gap (blue colored), although the edge states in both gaps have the same distance to the nearest (upper) bulk bands, which excludes the effect of decay length due to bulk-edge frequency difference. Interestingly, a power-law behavior is discovered in the decay profile of the edge states, which reveals the modal property of the quasiperiodic crystals, as predicted theoretically in ref. 40.

Discussion

In this work, we experimentally mapped the Hofstadter butterfly and fractal edge spectra using a 3D-printed reconfigurable acoustic quasicrystal, and first time used DOS instead of the transmittance/reflectance of the acoustic waves to construct the butterfly spectrum. Our approach can be easily extended to other systems, such as LC circuits, or arrays of silicon ring resonators41, which may possess higher-quality factors, thus offering the ability of mapping richer features in the spectrum. For example, if the parameter ϕ is an irrational number, or the integer p (coprime with q) is very large, the very high order fractal gaps and their associated edge states can be observed in the spectrum for the case of high-quality factor resonators [see Supplementary Fig. 4]. Thus, the larger the quality factor of the modes, the finer fractal features may be observed. In addition, the idea of reconfigurable design can be generalized to systems emulating higher dimensions, for example by mapping the effects of second or third Chern number in 4- and 6-dimensional spaces, implemented in 2- and 3-dimensional quasicrystals, respectively. Such systems may enable the exploration of even more subtle phenomena, which may be unfeasible in periodic topological systems. Our work opens up the possibility of realizing topological devices with robust performance stemming from the fundamental physics of quasiperiodic topological systems.

Methods

Experimental details

The reconfigurable quasiperiodic array in Fig. 1b has a lattice period a0 = 30 mm modulated by the spatial periodic parameter p. The maximum height of a single cylinder in Fig. 1a is chosen as \(h_t = h_0 + \delta h_0\), where h0 = 40 mm is the unperturbed height, \(\delta h_0 = 0.12h_0\) is the modulation depth, and variable δh is modulated by the sinusoidal function in the range of \([ - \delta h_0,\delta h_0]\). The diameter of cylinder d0 = 20 mm. The connectors between the cylinders have a diameter dc = 10 mm, with a vertical distance to the bottom of the hollow chamber hc = 5.2 mm. Narrow probe channels were intentionally introduced on top and bottom sides of each of the cylinders to excite and measure local pressure field at each site. The diameter of the port is d0 = 2 mm.

B9Creator v1.2 3D printer was used to print the reconfigurable model. All resonators and pistons were made with acrylic-based light-activated resin, a type of plastic that hardens when exposed to UV light. The shell of the resonator was printed with a sufficient thickness (2–3 mm) to ensure a hard wall boundary condition. Two connected cells were printed at a time and the cells were designed in a way to interlock tightly with each other.

The frequency generator and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) spectrum analyzer scripted in LabVIEW were used in the data processing. For the details of measurement, the speaker was placed at the bottom port and the microphone at the top port of the same site. Both the speaker and microphone were closely touched with the ports to achieve the maximum coupling between source and the system, as well as maximum amplitude of signal. The frequency generator was used to run a sweep from 3600 to 5800 Hz in 20 Hz intervals and with the dwell time of 0.5 s which is enough for the FFT spectrum analyzer to obtain the stable amplitude responses φ(f) at each frequency. For the calculation of normalized DOS, field distributions φ(i, f) are obtained by repeating this process for each site \(i \in [2,q - 1]\). The data for each site was normalized on the total volume of signal summed over frequencies and sites, as well as on the free space amplitude response between the microphone and the speaker, \({\mathrm{\Phi }}\left( {i,f} \right) = \varphi \left( {i,f} \right)/\mathop {\sum }\nolimits_{f,i} \varphi \left( {i,f} \right)/{\mathrm{\varphi }}_{{\mathrm{air}}}\left( f \right)\). The signal spectrum for an array of q−2 resonators \(S_n\left( f \right) = \mathop {\sum }\nolimits_i {\mathrm{\Phi }}\left( {i,f} \right)\). To observe the field distribution excited by the speaker, the speaker was placed at the port of the site of interest, and the microphone over each site of the array to measure the magnitude at the desired frequency. In all acoustic measurements, the noise floor in the signal is less than −120 dB, which is much less than the signal level in the desired frequency interval.

Numerical details

For the first-principle calculations, the finite element solver Multiphysics COMSOL 5.2a and the Acoustic module were used to perform full-wave simulation. In the acoustic propagation wave equation, the speed of sound was set as c = 343.2 m/s, and density of air as \(\rho = 1.225 {\,}{\rm{kg}/m^3}\). The dimensions of the structure are the same as the fabricated ones. For eigenvalue calculations, the continuity conditions were imposed along the ends of the quasiperiodic array. For the calculations of edge states spectrum, perfect matched layer boundary conditions were applied on the boundaries of the array. Coupled model equations were used to fit the physical parameters of the cells, calculate the Hofstadter butterfly spectrum and topological edge spectrum. For the two coupled resonators, the fitted onsite frequency is f0 ∼ 4502 Hz, coupling strength is κ ∼ 270 Hz.

Data availability

Data that are not already included in the paper and/or in the Supplementary Information are available on request from the authors.

References

Peierls, R. Zur Theorie des Diamagnetismus von Leitungselektronen. Z. Phys. 80, 29 (1933).

Harper, P. G. Single band motion of conduction electrons in a uniform magnetic field. Proc. Phys. Soc. A 68, 874–878 (1955).

Hofstadter, D. R. Energy-levels and wave-functions of bloch electrons in rational and irrational magnetic-fields. Phys. Rev. B. 14, 2239–2249 (1976).

Aubry, S. & Andre, G. Analyticity breaking and anderson localization in incommensurate lattices. Ann. Isr. Phys. Soc. 3, 18 (1980).

Avila, A. & Jitomirskaya, S. in Mathematical Physics of Quantum Mechanics, Vol. 690 (eds Joachim, A. & Alain, J.) 5–16 (Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 2005).

Prodan, E. Virtual topological insulators with real quantized physics. Phys. Rev. B 91, 245104 (2015).

Apigo, D. J., Qian, K., Prodan, C. & Prodan, E. Topological edge modes by smart patterning. Phys. Rev. Materials 2, 124203 (2018).

Schlosser, T., Ensslin, K., Kotthaus, J. P. & Holland, M. Landau subbands generated by a lateral electrostatic superlattice-chasing the Hofstadter butterfly. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 11, 1582–1585 (1996).

Albrecht, C. et al. Evidence of Hofstadter’s fractal energy spectrum in the quantized Hall conductance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 147–150 (2001).

Jaksch, D. & Zoller, P. Creation of effective magnetic fields in optical lattices: the Hofstadter butterfly for cold neutral atoms. New J. Phys. 5, 56 (2003).

Aidelsburger, M. et al. Realization of the Hofstadter Hamiltonian with ultracold atoms in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 185301 (2013).

Miyake, H., Siviloglou, G. A., Kennedy, C. J., Burton, W. C. & Ketterle, W. Realizing the Harper Hamiltonian with laser-assisted tunneling in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 185302 (2013).

Kuhl, U. & Stockmann, H. J. Microwave realization of the Hofstadter butterfly. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 3232–3235 (1998).

Richoux, O. & Pagneux, V. Acoustic characterization of the Hofstadter buttery with resonant scatterers. Europhys. Lett. 59, 34–40 (2002).

Dean, C. R. et al. Hofstadter’s butterfly and the fractal quantum Hall effect in moire superlattices. Nature 497, 598–602 (2013).

Hunt, B. et al. Massive Dirac Fermions and Hofstadter Butterfly in a van der Waals Heterostructure. Science 340, 1427–1430 (2013).

Ponomarenko, L. A. et al. Cloning of Dirac fermions in graphene superlattices. Nature 497, 594–597 (2013).

Kumar, R. K. et al. High-order fractal states in graphene superlattices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 5135–5139 (2018).

Roushan, P. et al. Spectroscopic signatures of localization with interacting photons in superconducting qubits. Science 358, 1175–1178 (2017).

Avron, J. E., Osadchy, D. & Seller, R. A topological look at the quantum Hall effect. Phys. Today. 56, 38–42 (2003).

Lohse, M., Schweizer, C., Price, H. M., Zilberberg, O. & Bloch, I. Exploring 4D quantum Hall physics with a 2D topological charge pump. Nature 553, 55–58 (2018).

Zilberberg, O. et al. Photonic topological boundary pumping as a probe of 4D quantum Hall physics. Nature 553, 59–62 (2018).

Kraus, Y. E., Lahini, Y., Ringel, Z., Verbin, M. & Zilberberg, O. Topological states and adiabatic pumping in quasicrystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 106402 (2012).

Kraus, Y. E. & Zilberberg, O. Topological equivalence between the Fibonacci quasicrystal and the Harper Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 116404 (2012).

Martinez, A. J., Porter, M. A. & Kevrekidis, P. G. Quasiperiodic granular chains and Hofstadter butterflies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 376, 20170139 (2018).

Padavic, K., Hegde, S. S., DeGottardi, W. & Vishveshwara, S. Topological phases, edge modes, and the Hofstadter butterfly in coupled Su-Schrieffer-Heeger systems. Phys. Rev. B 98, 024205 (2018).

Apigo, D. J., Cheng, W., Dobiszewski, K. F., Prodan, E. & Prodan, C. Observation of topological edge modes in a quasi-periodic acoustic waveguide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 095501 (2019).

Koshino, M., Aoki, H., Kuroki, K., Kagoshima, S. & Osada, T. Hofstadter butterfly and integer quantum Hall effect in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 1062–1065 (2001).

Kraus, Y. E., Ringel, Z. & Zilberberg, O. Four-dimensional quantum Hall effect in a two-dimensional quasicrystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, (2013).

Prodan, E. & Shmalo, Y. The K-theoretic bulk-boundary principle for dynamically patterned resonators. J. Geom. Phys. 135, 37 (2019).

Petrides, I., Price, H. M. & Zilberberg, O. Six-dimensional quantum Hall effect and three-dimensional topological pumps. Phys. Rev. B 98, 125431 (2018).

Bellissard, J. in From Number Theory to Physics (eds Waldschmidt, M. Moussa, P. Luck, J. M. & Itzykson, C.) (Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 1995).

Prodan, E. & Schulz-Baldes, H. Bulk and Boundary Invariants for Complex Topological Insulators: From K-Theory to Physics. (Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, 2016).

Prodan, E. Computational Non-commutative Geometry Program for Topological Insulators. (Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, 2017).

Thouless, D. J., Kohmoto, M., Nightingale, M. P. & Dennijs, M. Quantized hall conductance in a two-dimensional periodic potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 405–408 (1982).

Hatsugai, Y. Topological aspects of the quantum Hall effect. J. Phys. Condens. Mat. 9, 2507–2549 (1997).

Hatsugai, Y. Chern number and edge states in the integer quantum Hall-effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 3697–3700 (1993).

Kellendonk, J., Richter, T. & Schulz-Baldes, H. Edge current channels and Chern numbers in the integer quantum Hall effect. Rev. Math. Phys. 14, 87–119 (2002).

Ni, X., Weiner, M., Alu, A. & Khanikaev, A. B. Observation of higher-order topological acoustic states protected by generalized chiral symmetry. Nat. Mater. 18, 113–120 (2019).

Bandres, M. A., Rechtsman, M. C. & Segev, M. Topological photonic quasicrystals: fractal topological spectrum and protected transport. Phys. Rev. X 6, 011016 (2016).

Hafezi, M., Demler, E. A., Lukin, M. D. & Taylor, J. M. Robust optical delay lines with topological protection. Nat. Phys. 7, 907–912 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation with grants no. CMMI-1537294, EFRI-1641069, and DMR-1809915. X.N. thanks the support of Mina Rees Dissertation Fellowship at Graduate Center of CUNY. D.J.A., C.P. and E .P. acknowledge support from the W. M. Keck Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.P. and C.P. conceived the idea. X.N. designed and fabricated the sample. X.N., K.C. and M.W. performed the experiments. X.N. analyzed the data. X.N. and D.J.A. carried out the numerical simulations. X.N., E.P., A.A. and A.B.K. wrote the manuscript. A.B.K. directed the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ni, X., Chen, K., Weiner, M. et al. Observation of Hofstadter butterfly and topological edge states in reconfigurable quasi-periodic acoustic crystals. Commun Phys 2, 55 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0151-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0151-7

This article is cited by

-

Injection spectroscopy of momentum state lattices

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Hierarchies of Hofstadter butterflies in 2D covalent organic frameworks

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2023)

-

Revealing topology in metals using experimental protocols inspired by K-theory

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Topological acoustics

Nature Reviews Materials (2022)

-

Observation of bulk-edge correspondence in topological pumping based on a tunable electric circuit

Communications Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.