Abstract

Antiferromagnets possess a number of intriguing and promising properties for electronic devices, which include a vanishing net magnetic moment and thus insensitivity to large magnetic fields and characteristic terahertz frequency dynamics. However, probing the antiferromagnetic ordering is challenging without synchrotron-based facilities. Here, we determine the material parameters of the insulating iron oxide hematite, α-Fe2O3, using the surface sensitive spin-Hall magnetoresistance (SMR). Combined with a simple analytical model, we extract the antiferromagnetic anisotropies and the bulk Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya field over a wide range of temperatures and magnetic fields. Across the Morin phase transition, we show that the electrical response is dominated by the antiferromagnetic Néel vector rather than by the emergent weak magnetic moment. Our results highlight that the surface sensitivity of SMR enables access to the magnetic anisotropies of antiferromagnetic crystals, and also of thin films, where other methods to determine anisotropies such as bulk-sensitive magnetic susceptibility measurements do not provide sufficient sensitivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, various new effects have been discovered which enable easy and efficient ways to probe and manipulate the antiferromagnetic order (or Néel vector) by electrical current1,2,3. The Néel vector can be manipulated by electrical fields in magnetoelectric materials like Cr2O34 or multiferroics like BiFeO35, by bulk spin-galvanic effects in conducting antiferromagnets6,7, or by interfacial spin-orbit torques in multilayers with the insulating NiO8,9,10. For magneto-transport measurements, effects that are even functions of the magnetic order parameter like anisotropic11,12 and spin-Hall magnetoresistance (SMR)13,14,15 could be used to probe the antiferromagnetic state and detect switching events8,9,10. However, it is not obvious how one can extract the equilibrium state of an antiferromagnet and in particular determine from the field dependence of the SMR key magnetic properties such as the anisotropy values that are otherwise difficult to ascertain.

The SMR technique can probe the magnetic state of bilayer systems consisting of a ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic insulator and a heavy metal. In the simplest models [15,22,28], the longitudinal SMR signal ΔR is proportional to \(\left( {1 - \left( {{\mathbf{m}}\cdot {\mathbf{\mu }}} \right)^2} \right)\) for a ferromagnet and \(\left( {1 - \left( {{\mathbf{n}}\cdot {\mathbf{\mu }}} \right)^2} \right)\) for an antiferromagnet (where the unit vector μ of the spin-accumulation is perpendicular to the charge current J in the heavy metal and m and n are the magnetization and the Néel vector, respectively). As the magnetization in ferromagnets aligns along the external magnetic field, while the Néel vector of an antiferromagnet tends to align perpendicularly, ferro- and antiferromagnets should exhibit a different field dependence of the SMR signal on the external magnetic field. When the magnetic field is applied parallel to the current, the SMR contribution to the longitudinal resistance should increase for a ferromagnet (positive SMR) and should decrease for antiferromagnets (negative SMR). However, recent experiments show a more complicated behavior of SMR in antiferromagnets, with positive SMR in SrMnO316, negative SMR in the easy-plane NiO17,18, and both positive19,20 and negative21 SMR measured in the easy-axis antiferromagnet Cr2O3. To explain the different SMR signs, there were suggestions of mechanisms such as contributions from proximity induced magnetization21 or canted moments22. Additional complications stem from the possible strong dependence of the SMR response on the magneto-crystalline anisotropy resulting from structural symmetries23. However, such effects, can be concealed in multi-domain states17,24 by the presence of magneto-elastic coupling.

Hematite, α-Fe2O3, is not only the main component of rust, but also a prototypical insulating antiferromagnet that lends itself to disentangle the origins of the SMR signals in antiferromagnets and identify the role of easy-axis and easy-plane symmetries in the magnetoresistance response. This iron oxide has a hexagonal crystal structure \(R\bar 3c\), and at room temperature shows an easy-plane canted antiferromagnetic ordering in the basal crystallographic plane. It undergoes a magnetic phase transition at the Morin temperature25,26,27 (at about 260 K), below which it exhibits an easy-axis antiferromagnetic ordering along the c-axis. It also possesses a bulk Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya internal field28,29 along the c-axis, which is thus hidden in the easy-axis phase and which leads to a small (less than a millirad) canting angle between the magnetic sublattices, generating a weak moment in the easy-plane phase. Furthermore, hematite shows an accessible spin-flop field below 10 Tesla so that the Néel vector fully reorients perpendicular to external magnetic fields30. The size of the magnetic domains can exceed ten micrometers in both single crystals (see Supplementary Fig. 1) and thin films31 enabling long distance spin transport32, and domain redistribution in the easy-plane can be dominated by the coherent rotation of the Néel vector instead of domain wall motion. To understand the spin structures and the switching mechanisms, knowledge of the anisotropies and Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya (DMI) fields is crucial, which is however challenging in antiferromagnets using conventional approaches requiring large scale facilities.

In this article, we determine the antiferromagnetic anisotropies and the bulk Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya field of the insulating iron oxide hematite, α-Fe2O3, using a surface sensitive spin-Hall magnetoresistance (SMR) technique. We develop an analytical model that in combination with SMR measurements, allows for the identification of the material parameters of this prototypical antiferromagnet over a wide range of temperatures and magnetic field values. The SMR measurements are thus directly related to the equilibrium orientation of the Néel vector n calculated by minimizing the magnetic energy of the sample. The SMR response is shown to depend strongly on the direction of the charge current with respect to the magneto-crystalline anisotropies axes. Both the small net magnetization induced by the external magnetic field H or by the bulk Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya HDMI above the Morin transition, do not significantly contribute to the electrical response in the canted easy-plane phase. These results demonstrate that the SMR technique is a powerful and alternative tool to the complex neutron scattering33 or X-ray29 based measurements to ascertain not only the orientation of the Néel vector as demonstrated previously, but also to extract key parameters such as the magnetic anisotropies and DMI fields in antiferromagnets.

Results

Analytical Model

We first develop the necessary model that allows us to analyze the results of the SMR transport experiments. We assume that the SMR signal depends only on the components of the Néel vector22,28:

where j, k = x, y, are the coordinates along and perpendicular to the current direction within the sample plane, the constant ρ0 depends on the spin-mixing conductance at the Pt-hematite interface and is considered as a fitting parameter. The unit vector of spin-accumulation µ lays within the xy plane and is perpendicular to the current. The equilibrium orientation of the Néel vector n is calculated by minimizing the potential energy (per unit volume)

where Hex parametrizes the exchange field which keeps the magnetic sublattices antiparallel, HDMI is the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya field, Ms is the sublattice magnetization, n and m are the Néel vector and magnetization of the antiferromagnet related by the conditions \({\mathbf{{n}}}\cdot{\mathbf{m}}\) = 0 and \({\mathbf{n}}^2 + {\mathbf{m}}^2 = 1\). The coordinate frame XYZ is related to the crystallographic axes and differs from the xyz frame defined by the surface plane of the R-cut hematite sample (x being the projection of the easy axis Z in the sample plane, y the axis perpendicular to it) and its normal z. The anisotropy energy of the antiferromagnet depends on two parameters:

The temperature-dependent uniaxial anisotropy field \(H_{2||}(T)\) is positive at low temperature, where it stabilizes the easy-axis phase with \({\mathbf{n}}||{\boldsymbol{Z}},\) and changes sign at the Morin temperature. The in-plane anisotropy field \(H_ \bot > \,0\) selects one of three equivalent easy axes in the easy-plane phase. We keep the in-plane anisotropy also in the easy-plane phase to remove degeneracy of states and avoid multiple solutions. Based on the previously estimated values25,29,30,34 of the parameters, we assume that \(H_{{\rm{ex}}} \gg H_{{\rm{DMI}}} \gg H_{2||},H_ \bot\), and, hence, \(m \ll n \approx 1.\)

The external magnetic field induces a rotation of the Néel vector towards a direction perpendicular to the magnetic field. In the easy-axis phase \(\left( {H_{2||} \ > \ 0} \right)\), the final state with \({\mathbf{n}} \bot {\mathbf{H}}\) can be achieved either by a spin-flop or by a smooth reorientation, depending on the orientation of the magnetic field with respect to the easy axis. A spin-flop takes place at a critical value \(H_{{\rm{sf}}} = \sqrt {H_{{\rm{ex}}}H_{{\rm{an}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}}\) when H is parallel to the easy-axis and competes with the effective anisotropy field \(H_{{\rm{an}}}^{{\rm{eff}}} = H_{2||} - H_{{\rm{DMI}}}^2/H_{{\rm{ex}}}\). If, in contrast, H is perpendicular to the easy-axis, the DMI field pulls the magnetization along the applied field and simultaneously induces a smooth rotation of the Néel vector into the state with \({\mathbf{n}} \bot {\mathbf{H}}\) and \({\mathbf{n}} \bot {\mathbf{Z}}\). In this case, the final state is achieved at the critical field \(H_{{\rm{DMI}},{\rm{sf}}} = H_{{\rm{sf}}}^2/H_{{\rm{DMI}}}\). For a generic configuration with H forming an angle \(\chi _H\) with the easy axis, the critical field required for a reorientation is

By fitting the angular dependence of the critical field with Eq.(4), we can then determine the parameters \(H_{{\rm{sf}}}\) and \(H_{{\rm{DMI}},{\rm{sf}}}\), and calculate the anisotropy and DMI fields, as it will be discussed below.

Spin-Hall magnetoresistance below the Morin transition

Experimentally, we access the antiferromagnetic properties of hematite using Hall bar devices (Fig. 1a), aligned along the projection of the c-axis in the R-plane (x-axis) or perpendicular to it (y-axis). To determine the role of the crystal anisotropies in the SMR response, we first perform measurements at T = 200 K below the Morin temperature (TM = 260 K) in the easy-axis phase with zero magnetization (m = 0) and measure the SMR signal by rotating the magnetic field in the sample plane.

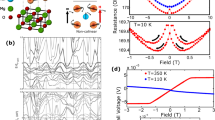

Spin-Hall magnetoresistance (SMR) for Pt Hall bars deposited along the y-axis (direction of the injected current) of the R-cut single crystal of hematite. a Schematic of the devices b The longitudinal SMR response as a function of the magnetic fields applied along x (red), y (black) and z (green) axes. c, d Angular dependence of the longitudinal (c) and transverse (d) SMR for different field values 6 (magenta), 8 (blue) and 11 teslas (black). The magnetic field rotates within the xy plane, α is the in-plane angle between Jy and H. Theoretical curves (solid lines) are calculated based on the model (1–3) with \({{H}}_{{{{\rm{an}}}}}^{{{{\rm{eff}}}}} =\) 23.8 mT, \({{H}}_ \bot =\) 1.54 μT, \({{H}}_{{{{\rm{DMI}}}}} =\) 2.72 T, and \({{H}}_{{\rm{ex}}} =\) 1040 T34. The sample temperature is 200 K. Error bars (not visible, smaller than the symbol size) account for the standard error

For devices directed along y, we measure the field-dependence of the SMR signal when applying a magnetic field in three directions: parallel (x and y directions) and perpendicular (z direction) to the sample plane, as shown in Fig. 1b. We define the SMR zero signal to be the value at zero field. When the magnetic field is applied in the sample plane perpendicular to the current Jy, H||x, the SMR signal increases monotonically until it reaches the critical field \(H_{cr}\left( {{{\chi }}_{{H}} = 33^{\mathrm{o}}} \right) = 6\) T, which corresponds to the transition into the “spin-flop” state with \({\mathbf{n}} \bot {\mathbf{H}}\). In this state the Néel vector is parallel to the current and does not contribute to the SMR signal, which reaches its maximal value. When the applied magnetic field is perpendicular to the easy axis, H||y, the SMR signal shows a non-monotonic field dependence, which can be interpreted as a rotation of the Néel vector in the xz plane according to theoretical predictions (solid line in Fig. 1b). In this configuration, the magnetic field induces a small magnetization along y and the equilibrium orientation of the Néel vector is defined by the competition of the DMI and the easy-axis anisotropy. Above the critical field \(H_{{\rm{cr}}}\left( {90^{\mathrm{o}}} \right) = H_{{\rm{DMI}},{\rm{sf}}} \approx 10\) T, the Néel vector reaches its final state perpendicular to the easy axis (and almost perpendicular to the sample plane) with a minor projection on the direction of the spin accumulation μ. This is seen as the saturation of the SMR signal. Note that we can interpret the experimental data using only the model of pure SMR14,15, without the need to resort to any proximity effect-induced anisotropic magnetoresistance12, which would not lead to a change of magnetoresistance for this magnetic transition in the plane perpendicular to the applied current. Finally, for H || z, we observe a monotonic field dependence with an intermediate value of the critical field \(H_{cr}\left( {57^{\mathrm{o}}} \right) = 6\) T, as expected for an angle of 57° between the applied field and the easy-axis. The agreement between the theoretical model (1)–(3) and experiment indicates that the main contribution to the SMR signal originates from the Néel vector n and the contribution of the small induced magnetic moment m to the SMR is not significant.

Figure 1c–d, show the angular dependences of the longitudinal and transverse SMR signal measured for the fields around the minimal critical field (6 T), above the maximal critical field (11 T), and also for an intermediate field value (8 T). The magnetic field is rotated within the sample plane, the in-plane angle α is measured relative to the current direction Jy, as shown in Fig. 1a. In all cases, the longitudinal SMR signal shows a negative sign (i.e a maximum resistance is achieved for the magnetic field applied perpendicular to the injecting current). The amplitude of the SMR angular dependence peaks at the spin-flop field (H = 6 T), when the Néel vector spans all possible states within the sample plane xy. In contrast, for the rotation at H = 11 T, the Néel vector varies between two “spin-flop” states (along X and Y crystallographic axes) with minor projections on the spin-accumulation axis x. This explains the lower value of the SMR signal. The transverse SMR signal (Fig. 1d) shows similar behavior with a maximal amplitude at 6 T.

Reasonable agreement between experimental data and theoretical modelling for all angular and field dependences of the SMR signal shows that our single-domain approximation is sufficient to describe the system and allows us to estimate the values for the DMI constant and \(H_{{\rm{an}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}\) based on the minimal and maximal values of critical fields (in combination with the reported value of the exchange field (Hex = 1040 T34). However, these parameters can be determined directly with higher accuracy from fitting the angular dependence of the critical field Hcr measured by rotating the magnetic field in the xz plane, see Fig 2.

Longitudinal Spin-Hall magnetoresistance (SMR) in the β-plane of Pt Hall bars deposited along the y-axis. a Field dependence of the longitudinal SMR signal for magnetic fields applied parallel (β = −30o) and perpendicular (β = 60o) to easy axis and for two intermediate orientations in the xz plane (β = 0o and 90o). b Dependence of the longitudinal SMR (color code) as a function of the amplitude and direction of the magnetic field in the xz plane calculated from the model (1)–(3) with \({{H}}_{{\rm{an}}}^{{\rm{eff}}} =\) 23.8 mT, \({{H}}_ \bot =\) 1.54 μT, and \({{H}}_{{\rm{DMI}}} =\) 2.72 T. Solid line (theory) and dots (experiment) show the angular dependence of the critical field. Vertical arrows correspond to the extracted critical fields. (a). The angle β is calculated from x-axis, the current is applied along y, as shown in Fig. 1a. In calculations we account for a shift between crystallographic and experimental axes, \({{\chi }}_{{H}} = ({{\beta }} + 33)^\circ\). The sample temperature is T = 200 K. Error bars (if not visible, smaller than the symbol size) account for (a) the standard error, (b) fit parameters errors and saturation field uncertainty

Angular dependence of the critical fields in presence of DMI

Figure 2 shows the results of such measurements for a Pt Hall bar directed along y. In Fig. 2a. we demonstrate typical field dependences of the longitudinal SMR for different orientations of the magnetic field. When the magnetic field is almost parallel to the easy axis (β = −30°), the SMR curve changes step-wise, thus reflecting the spin-flop reorientation of the Néel vector. The decrease of the signal in the near-spin-flop region originates from small (3°) misalignment of the field which induces tilting of the Neel vector from z axis. Such an abrupt transition is typical for easy-axis antiferromagnets, which can possess only indistinguishable 180o domains. This behavior is in contrast with the smooth variation of the SMR signal in easy-plane antiferromagnets, where the magnetic field can induce domain wall motion between non-180o domains17,24. For other field directions, the SMR signal varies smoothly, in accordance with theoretical predictions (solid lines). The critical field in these cases is associated with the points of saturation of the SMR signal (vertical arrows). We can further exclude a contribution from a magnetic proximity effect in the platinum due to both the sign of the magnetoresistance, the absence of a spin-reorientation at low magnetic fields, and the absence of XMCD signals (Supplementary Fig. 1 & Note 1).

In Fig. 2b. we present the full field-angular dependence of the longitudinal SMR signal calculated according to Eqs. (1)–(3). The black solid line delineates the region of the spin-flop state (with \({\mathbf{n}} \bot {\mathbf{H}}\)) and the corresponding saturation of the SMR signal. This line, determined from Eq. (4), coincides with the experimental angular dependence of the critical field \(H_{{\rm{cr}}}\left( {\chi_H} \right)\). By fitting the experimental data \(H_{{\rm{cr}}}\left( \beta \right)\) (dots) with the predicted dependence \(H_{{\rm{cr}}}\left( {\chi _H} \right)\) (taking into account that \(\chi _H = \beta + 33^\circ\)), we extract the values of the internal DMI and effective anisotropy fields as HDMI = 2.72 T and \(H_{{\rm{an}}}^{{\rm{eff}}} =\)23.8 mT. These values are consistent with the previous measurements35 and show that the simple surface-sensitive electrical measurements allow for a direct and precise access to the magnetic state and properties of antiferromagnetic system.

Role of the anisotropy axis in the electrical read-out

In antiferromagnets, the SMR response strongly depends on the orientation of the anisotropy axis relative to the patterned devices. Contrary to ferromagnets with low anisotropies like YIG or NiFe, the projection of the Néel vector along the spin-accumulation can even be zero as long as the applied magnetic fields are lower than the large critical fields. To identify and corroborate the role of anisotropy fields in the transport measurements, we thus repeat the measurements for Pt Hall bars rotated by 90°, with injected currents parallel to the x-axis (Fig. 3a). For this geometry of the devices, the Néel vector is perpendicular to the spin-accumulation at zero field. The field dependences of the longitudinal SMR measured for H||x and H||z (Fig. 3b) are in good agreement with the theoretical model (Eqs. (1)–(3)) and show the same critical fields (6 and 8 T respectively) as the devices with a y-oriented electrode. For H||y the SMR signal is nearly constant, as the Néel vector rotates in the plane perpendicular to the spin-accumulation. In this case, the SMR response does not reflect the Néel reorientation observed for Pt devices directed along y. The small quantitative discrepancy between the theoretical model and the experiments at high magnetic fields, larger than the critical fields, could be associated with a residual contribution from the emerging canted moment and from the limitations of our analytical model. The angular dependences of the longitudinal (Fig. 3c) and transverse (Fig. 3d) SMR are negative, in agreement with the model predictions (Eq. 1). This further confirms that we indeed measure a pure SMR effect with no significant proximity induced magnetic moment contributions. Note that in spite of a visual difference in the SMR dependences measured for x- and y-oriented devices, all the data can be consistently interpreted within the same theoretical model that we develop. This also means that SMR signal must be analyzed taking into account the device orientation relative to the crystallographic axis. In our case, information from the x-oriented devices is limited, due to the absence of an electrical signature of the DMI induced reorientation for H||y.

Spin-Hall magnetoresistance (SMR) for Pt Hall bars deposited along the x-axis (direction of the injected current) of the R-cut single crystal of hematite. a Schematic of the devices, α is the angle between Jx and H. b The longitudinal SMR response as a function of the magnetic fields applied along x (red), y (black) and z (green) axes (c-d) Angular dependence of the longitudinal (c) and transverse (d) SMR for different field values 8 (blue) and 11 T (black). Error bars (not visible, smaller than the symbol size) account for the standard error

Spin-Hall magnetoresistance through the Morin phase transition

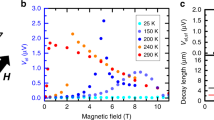

Finally, the SMR technique allows one to probe the equilibrium states of hematite over a wide temperature range to study the (T, H) magnetic phase diagram. To illustrate this, we measure field dependences of the longitudinal SMR for x-oriented devices at different temperatures (see Fig. 4a), below and above the Morin transition temperature which separates the easy-axis and easy-plane phases. Extracted values of the critical fields (closed black dots) are shown in Fig. 4b as a function of temperature. Within the interval 160–255 K, the temperature dependence of the critical field is well described by \(H_{{\mathrm{cr}}}(T) \propto {\sqrt{T_{\mathrm{M}} - T}}\), with \(T_{\mathrm{M}} = 255\, {\mathrm{K}}\). Such a temperature dependence is typical for the second-order phase transitions within the Landau theory and was also reported earlier34,36. Below 160 K, \(H_{{\rm{cr}}}\left( T \right)\) stays around a constant value of 8 T, above 255 K its value is close to zero. Using Eq. (4) and the experimental dependence \(H_{{\rm{cr}}}\left( T \right)\), we then determine the temperature dependence of the effective anisotropy \(H_{{\mathrm{an}}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\left( T \right)\) (blue line in Fig. 4b) assuming that HDMI = 2.72 T is temperature-independent (as previously found35,37). The last assumption is consistent with the observed (open dots in Fig. 4b) and predicted (solid line) temperature dependence of the maximal critical field. Note, that as the SMR is a surface sensitive technique, similar measurements could determine the magnetic anisotropies of high quality epitaxial hematite thin films31, for which magnetometry measurements such as SQUID do not provide sufficient sensitivity. Indeed, one can notice here the excellent agreement between previous bulk measurements and the measurements and theory presented here with a surface sensitive technique. This also indicates that the surface and the bulk of the crystal have similar anisotropies.

Temperature dependence of the Spin-Hall magnetoresistance (SMR). a Field dependence of the longitudinal SMR for H parallel to J (||x) at different temperatures (below and above the Morin temperature of 260 K). b Temperature dependence of the critical field Hcr (left axis) for H||x (\({{H}}_{{\rm{cr}}}\left( {{{T}};{{\chi }}_{{H}} = 33^{\mathrm{o}}} \right)\), black dots) and H||y (\({{H}}_{{\rm{cr}}}\left( {{{T}};{{\chi }}_{{H}} = 90^{\mathrm{o}}} \right)\), blue dots). Solid lines shows the fitting with \({{H}}_{{\rm{cr}}} \propto \sqrt {{{T}}_{\rm{M}} - {{T}}}\). Blue line (right axis) shows the calculated temperature dependence of the effective anisotropy \({{H}}_{{\rm{an}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}({{T}})\) based on fitting of critical fields and Eq. (4). c Schematic of the two device orientations (J||y and J||x). Shaded is the easy plane with orientations (double-arrows) of the Neel vectors in different domains. d Angular dependence of the longitudinal SMR signal for J||y (green) and J||x (brown) at H = 0.5 T (full dots) and H = 5.5 T (open dots) in easy-plane phase (T = 280 K). Field is rotated in the xy plane, angle α is calculated from the current direction. Symbols are experimental data; solid lines correspond to fitting with \({{H}}_{{\rm{an}}}^{{\rm{eff}}} =\) 23.8 mT, \({{H}}_ \bot =\) 1.54 μT, and \({{H}}_{{\rm{DMI}}} =\) 2.72 T. Error bars (if not visible, smaller than the symbol size) account for (a & d) the standard error, (b) fit parameters errors and saturation field uncertainty

According to the theoretical model, the effective anisotropy vanishes at the Morin temperature, \(H_{{\rm{an}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}\left( {T_{\rm{M}}} \right) = 0\), and changes sign and becomes negative in an easy-plane phase (above \(T_{\rm{M}}\)). However, the SMR signal at 260 and 300 K still shows the features of the spin-flop transition at small field around 0.4 T (Fig. 4a), a feature also observed in neutron diffraction and resonance measurements [33, 37]. Moreover, the SMR has the same sign below and above TM which indicates that the SMR is still dominated by the Néel vector and not by the small canted moment. Assuming that reorientation of the Néel vector in the easy-plane phase (represented in Fig. 4c) is driven mainly by in-plane anisotropy (Eq. 3), we estimate the value of the in-plane anisotropy field \(H_ \bot\) from the angular dependences of the SMR measured for small (0.5 T) and large (5.5 T) fields applied in the xy plane and for the two orientations of the Pt stripes (Fig. 4d). As seen from Fig. 4d, the amplitude of the SMR signal remains the same for small and large fields. According to theoretical predictions this means that the critical field in the easy-plane phase is below 0.4 T, which gives \(H_ \bot \le 1.6\) μT. The weak field-dependence of the SMR amplitude also means that the field-induced “weak” magnetic moment only contributes negligibly. Note, that for geometrical reasons, the SMR amplitude is larger for x-oriented device demonstrating again the role of the crystal and device symmetry in the electrical response.

Discussion

We have combined theory with experiments to analyze the properties of the insulating antiferromagnetic hematite, α-Fe2O3, using accessible transport measurements. We successfully model Spin-Hall magnetoresistance measurements in α-Fe2O3 by a simple analytical model. From comparison and fitting of our electrical measurement results, we determine the values of anisotropy and Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya fields, which drive the Néel vector reorientation. Measuring the SMR across the Morin transition, we determined the specific properties of the easy-axis and canted easy-plane phases, and observed that the contribution of the weak moments is negligible for the electrical response, which is governed by the Néel vector. The shape of the SMR curves strongly depends on the orientation of the devices with respect to the crystallographic axis in line with our model predictions. Our observations demonstrate that the Spin-Hall magnetoresistance technique is a unique surface sensitive technique that allows us to easily access to the fundamental properties of insulating antiferromagnets without the need to resort to large scale facility measurements as previously required.

Methods

Experimental setup

The devices were carried out based on a sample geometry that was defined using electron beam lithography and the subsequent deposition and lift-off of a 7 nm platinum layer by DC sputtering in an argon atmosphere at a pressure of 0.01 mbar. The devices were contacted using a bilayer of chromium (6 nm) and gold (32 nm). The sample was mounted to a piezo-rotating element in a variable temperature insert that was installed in a superconducting magnet capable of fields up to 12 T and cooled with liquid helium. For the rotation measurements, the sample was rotated in a constant field.

Single crystal of α-Fe2O3

The single crystal of hematite, α-Fe2O3, was obtained commercially and has an R-cut orientation, which means that the c-axis of the hexagonal structure is tilted 34 degrees below the surface plane. This orientation was chosen because of the large in-plane projection of the c-axis in addition to the stability of the sample terminating with the r-plane.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to R.L. or M.K.

References

Gomonay, H. V. & Loktev, V. M. Spin transfer and current-induced switching in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 81, 144427 (2010).

MacDonald, A. H. & Tsoi, M. Antiferromagnetic metal spintronics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 369, 3098–3114 (2011).

Shick, A. B., Khmelevskyi, S., Mryasov, O. N., Wunderlich, J. & Jungwirth, T. Spin-orbit coupling induced anisotropy effects in bimetallic antiferromagnets: A route towards antiferromagnetic spintronics. Phys. Rev. B 81, 212409 (2010).

Kosub, T. et al. Purely antiferromagnetic magnetoelectric random access memory. Nat. Commun. 8, 13985 (2017).

Lebeugle, D. et al. Electric-field-induced spin flop in BiFeO3 single crystals at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 227602 (2008).

Wadley, P. et al. Electrical switching of an antiferromagnet. Science 351, 587–590 (2016).

Bodnar, S. Y. et al. Writing and reading antiferromagnetic Mn2Au by Néel spin-orbit torques and large anisotropic magnetoresistance. Nat. Commun. 9, 348 (2018).

Chen, X. Z. et al. Antidamping-torque-induced switching in biaxial antiferromagnetic insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 207204 (2018).

Moriyama, T., Oda, K., Ohkochi, T., Kimata, M. & Ono, T. Spin torque control of antiferromagnetic moments in NiO. Sci. Rep. 8, 14167 (2018).

Baldrati, L. et al. Mechanism of Neel order switching in antiferromagnetic thin films revealed by magnetotransport and direct imaging. https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.11326 (2018).

McGuire, T. & Potter, R. Anisotropic magnetoresistance in ferromagnetic 3d alloys. IEEE Trans. Magn. 11, 1018–1038 (1975).

Azevedo, A., Vilela-Leão, L. H., Rodríguez-Suárez, R. L., Lacerda Santos, A. F. & Rezende, S. M. Spin pumping and anisotropic magnetoresistance voltages in magnetic bilayers: Theory and experiment. Phys. Rev. B 83, 144402 (2011).

Nakayama, H. et al. Spin Hall Magnetoresistance Induced by a Nonequilibrium Proximity Effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 206601 (2013).

Manchon, A. Spin Hall magnetoresistance in antiferromagnet/normal metal bilayers. Phys. Status Solidi RRL – Rapid Res. Lett. 11, 1600409(2017).

Chen, Y.-T. et al. Theory of spin Hall magnetoresistance. Phys. Rev. B 87, 144411 (2013).

Han, J. H. et al. Antiferromagnet-controlled spin current transport in SrMnO3/Pt hybrids. Phys. Rev. B 90, 144431 (2014).

Baldrati, L. et al. Full angular dependence of the spin Hall and ordinary magnetoresistance in epitaxial antiferromagnetic NiO(001)/Pt thin films. Phys. Rev. B 98, 024422 (2018).

Hoogeboom, G. R., Aqeel, A., Kuschel, T., Palstra, T. T. M. & van Wees, B. J. Negative spin Hall magnetoresistance of Pt on the bulk easy-plane antiferromagnet NiO. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 052409 (2017).

Ji, Y. et al. Spin Hall magnetoresistance in an antiferromagnetic magnetoelectric Cr2O3/heavy-metal W heterostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 262401 (2017).

Schlitz, R. et al. Evolution of the spin hall magnetoresistance in Cr2O3/Pt bilayers close to the Néel temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 132401 (2018).

Ji, Y. et al. Negative spin Hall magnetoresistance in antiferromagnetic Cr2O3/Ta bilayer at low temperature region. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 232404 (2018).

Ganzhorn, K. et al. Spin Hall magnetoresistance in a canted ferrimagnet. Phys. Rev. B 94, 094401 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Antiferromagnetic anisotropy determination by spin Hall magnetoresistance. J. Appl. Phys. 122, 083907 (2017).

Fischer, J. et al. Spin Hall magnetoresistance in antiferromagnet/heavy-metal heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 97, 014417 (2018).

Moriya, T. Anisotropic Superexchange Interaction and Weak Ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91–98 (1960).

Ellis, D. S. et al. Magnetic states at the surface of α-Fe2O3 thin films doped with Ti, Zn, or Sn. Phys. Rev. B 96, 094426 (2017).

Morin, F. J. Electrical properties of α-Fe2O3 containing titanium. Phys. Rev. 83, 1005–1010 (1951).

Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of “weak” ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 4, 241–255 (1958).

Miyawaki, J. et al. Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in α-Fe2O3 measured by magnetic circular dichroism in resonant inelastic soft x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. B 96, 214420 (2017).

Elliston, P. R. & Troup, G. J. Some antiferromagnetic resonance measurements in α-Fe 2 O 3. J. Phys. C. Solid State Phys. 1, 169 (1968).

Bezencenet, O., Bonamy, D., Belkhou, R., Ohresser, P. & Barbier, A. Origin and tailoring of the antiferromagnetic domain structure in α-Fe2O3 thin films unraveled by statistical analysis of dichroic spectromicroscopy (X-ray photoemission electron microscopy) images. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 107201 (2011).

Lebrun, R. et al. Tunable long-distance spin transport in a crystalline antiferromagnetic iron oxide. Nature 561, 222 (2018).

Poulis, N. J., Hardeman, G. E. G., van der Lugt, W. & Hass, W. P. A. Nuclear magnetic resonance and relaxation in zero field and near the threshold field. Physica 24, 280–288 (1958).

Besser, P. J., Morrish, A. H. & Searle, C. W. Magnetocrystalline anisotropy of pure and doped hematite. Phys. Rev. 153, 632–640 (1967).

Morrish, A. H. Canted Antiferromagnetism: Hematite. (World Scientific, 1995).

Foner, S. High-field antiferromagnetic resonance in α-Fe2O3. Phys. Rev. 130, 183 (1963).

Ovchinnikov, S. G., Rudenko, V. V. & Tugarinov, V. I. Temperature dependence of the uniaxial magnetic anisotropy of rhombohedral antiferromagnetic crystals with ions in the S state. Phys. Solid State 52, 112–116 (2010).

Acknowledgements

R.L. acknowledges the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement FAST number 752195. R. L., A. R. and M.K. acknowledge support from the DFG project number 423441604. A.R., J.S. and M.K. acknowledge support from the Graduate School of Excellence Materials Science in Mainz (DFG/GSC 266). O.G. and J.S. acknowledge the support from the Humboldt Foundation, the ERC Synergy Grant SC2 (No. 610115), the EU FET Open RIA Grant no. 766566, the DFG (project SHARP 397322108). L. B. acknowledges the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement ARTES number 793159. All authors from Mainz also acknowledge support from both MaHoJeRo (DAAD Spintronics network, project number 57334897) and SPIN+X (DFG SFB TRR 173). A.Q. and A.B. acknowledge support from the European Research Council via Advanced Grant number 669442 ‘Insulatronics’. S.A.B. and R.A.D. acknowledge support from Stichting voor Fundamenteel Onderzoek der Materie (FOM) and the European Research Council via Consolidator Grant number 725509 ‘SPINBEYOND’. A.Q., R.A.D., M.K. and A.B. were supported by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme, project number 262633 ‘QuSpin’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.L. and M.K proposed and supervised the project. R.L and A.R. performed the transport and SQUID experiments. A.R patterned the samples. R.L, L.B and F.K performed the XMLD measurements of the Supplemental. R.L, O.G, S. B, A.R. analysed the data. O.G. performed the analytical calculations with inputs from S.B, A.Q., J.S, A.B and R-A.D. R.L, O. G A.R. and M.K wrote the paper. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lebrun, R., Ross, A., Gomonay, O. et al. Anisotropies and magnetic phase transitions in insulating antiferromagnets determined by a Spin-Hall magnetoresistance probe. Commun Phys 2, 50 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0150-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0150-8

This article is cited by

-

Anisotropic long-range spin transport in canted antiferromagnetic orthoferrite YFeO3

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Reversible hydrogen control of antiferromagnetic anisotropy in α-Fe2O3

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Stabilization of a honeycomb lattice of IrO6 octahedra by formation of ilmenite-type superlattices in MnTiO3

Communications Materials (2020)

-

Long-distance spin-transport across the Morin phase transition up to room temperature in ultra-low damping single crystals of the antiferromagnet α-Fe2O3

Nature Communications (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.