Abstract

In the development of spin-based electronic devices, a particular challenge is the manipulation of the magnetic state with high speed and low power consumption. Although research has focused on the current-induced spin–orbit torque based on strong spin–orbit coupling, the charge-based and the torque-driven devices have fundamental limitations: Joule heating, phase mismatching, and overshooting. In this work, we investigate numerically and theoretically alternative switching scenario of antiferromagnetic insulator in one-dimensional confined nanowire sandwiched with two electrodes. As the electric field could break inversion symmetry and induce Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction and pseudo-dipole anisotropy, the resulting spiral texture takes symmetric or antisymmetric configuration due to additional coupling with the crystalline anisotropy. Therefore, by competing two spiral states, we show that the magnetization reversal of antiferromagnets is realized, which is valid in ferromagnetic counterpart. Our finding provides promising opportunities to realize the rapid and energy-efficient electrical manipulation of magnetization for future spin-based electronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the development of highly efficient spintronic devices, one emerging issue is to discover and exploit novel phenomena with strong spin–orbit coupling (SOC)1,2,3,4. Due to scientific and technological interest, intensive research has focused on current-driven spin–orbit torques (SOT) for manipulation of magnetization. Most of experimental and theoretical works on SOT switching have been performed in a magnetic multilayer consisting of an ultrathin ferromagnets (FMs) or antiferromagnets (AFMs) and heavy metal layers5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Because SOT devices use a current, charge scattering, and corresponding Joule heating inevitably occur21. This intrinsic property is an obstacle in reducing the switching power, although SOT efficiency is significantly improved in nanoscale devices7,10,22,23,24,25,26. In heterostructures, especially with structural inversion asymmetry, Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya (DM) interaction, which is also induced by spin–orbit coupling, has received attention in spin dynamics research. In the presence of DM interaction, the competition between exchange and DM interaction allows for a nontrivial topological spin configuration to exist as a ground state27,28,29,30, i.e., spiral configuration and skymion in a confined geometry. Topological robustness has been exploited to enhance the performance of SOT devices, such as DM interaction-stabilized Néel domain wall motion31,32,33,34 and DM interaction-assisted current-driven switching35. The DM interaction plays a secondary role in current-driven dynamics. However, it is rarely studied as a driving source to replace a current to initiate spin motion. Actually, a few studies performed on electric field-induced DM interactions found that the conversion efficiency is proportional to the spin–orbit coupling strength as in SOT36,37,38.

Here, we report an electric field-induced magnetization switching scenario through potential barrier modulation in a nanowire, instead of the spin current. This switching is realized by changing the ground spiral state and relaxing it into a switched configuration by controlling the DM interactions. This switching scenario is different from the precessional switching mechanism driven by external torques, efficiency of which relies upon the timing of the torque and magnetization precession.

Results

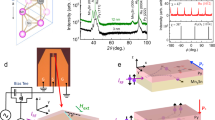

Figure 1 shows the spiral structure of antiferromagnetic insulator (AFI). Here, AFMs are aligned along the z axis and sandwiched by two electrodes of heavy and normal metal. We use two order parameters: the Néel order l = (si − sj)/2 and the ferromagnetic order parameter m = (si + sj)/2, where each spin is normalized by its magnitude si = Si/S0 with S0 = |Si|. Therefore, the wire length is defined as lw in Néel space. In heavy metal layer with strong SOC such as Pt, Ta, and W, spin Hall current is typically generated when a charge current is applied in those materials1,2. The magnetic crystalline anisotropy has an easy axis along the z axis where anisotropy constant Kz is positive. The geometric inversion asymmetry induces DM interaction along the y axis according to Dij ∝ \(\widehat {\bf{x}}\)×eij, where the x axis is normal to the interface and eij is the unit vector connecting neighbor spins si and sj27,28. We ignore this geometric DM interaction in the calculation and discuss it later. When the electric field along the x axis breaks inversion symmetry, the DM vector D, becomes effectively toward the y axis due to Dij ∝ E\(\widehat {\bf{x}}\) × eij27,28,36,37,38. Also, we introduce an electric-field-induced pseudo-dipolar anisotropy energy KE with easy plane, and it is induced from SOC that gives rise to the DM interaction27,28,36,37,38. An electric-field-induced anisotropy is an effect of order of E2, but cannot be ignored in our switching scenario. In other indirect exchange interactions, known as double-exchange and Ruderman-Kittel-Kasuya-Yosida (RKKY) interaction in metal, it has been reported that same SOC induces the DM interaction and the anisotropy by the external electric field39,40,41.

Schematics for antiferromagnetic spiral structure in Néel space. In a confined one-dimensional geometry, this spiral structure is formed by Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya (DM) interaction. When electric field is applied between two electrodes and DM interaction is induced, the DM vector between neighboring spins takes the form of Dij ∝ \(\widehat {\bf{x}}\)×eij, where eij is the unit vector linking neighbor spins i and j and therefore, Dij is parallel to the y axis. Here, spin–orbit torque with polarization along the y axis is applied to perturb the antiferromagnets

Two possible spiral states as a function of DM interaction

However, before preceding to the electric-field-induced manipulation of AFMs, we consider stationary states of AFMs as a function of DM interaction energy. Figure 2 shows two spiral structures with different DM interaction energies and these are formed by additional coupling with crystalline anisotropy, which is proportional to ~lz2 (see Eq. (1)). Under exchange approximation where the exchange energy J is the larger than other energies, or |J| ≫ Dy and Kz, we can assume that the spiral structure has continuously varying spin texture, (li+1-li)/Δ ∼ l′ = dl/dz and (mi+1-mi)/Δ ∼ m′ = dm/dz, where Δ is the interspacing of the nearest neighbors in Néel space. Therefore, the energy density E1D is described as

The a and A are the homogeneous and inhomogeneous exchange constants, respectively, and L is a parity-breaking exchange constant. Equation (1) is obtained in refs. 42,43, and the DM energy is derived in the Supplementary Note 1. The parameters are defined as A = Δ2J = J, a = 4J, L = ΔJ = J, Dy = Δdy/2 = dy/2 when Δ is set to the unit length. To estimate the equilibrium state of AFMs, we set the effective Néel vector as l = {lx, lz} = {sin[φ(z)], cos[φ(z)]} because ly is the spiral axis. Therefore, E1D is reduced as

where Ω ≡ (−A+3L2/a) = J/4 is defined as the effective exchange stiffness. After we use a standard variation of calculus to minimize total energy, Etotal,1D = \({\int}_1^{l_w} {E_{{\mathrm{1D}}}} dz\), we obtained two equations

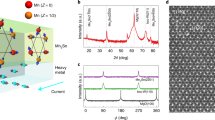

where \(\Lambda \equiv \sqrt {\Omega /K_{\mathrm{z}}}\) is the characteristic antiferromagnetic domain wall width. Equation (3a) shows the stationary configuration of AFMs and takes the form of a time-independent sine-Gordan (SG) model44. The solution of Eq. (3a) is given as a the trivial solution φ = 0 or the nontrivial solution φ = am(u|m). The nontrivial solution of SG equation is analytically obtained as φ(z) = am[\(\sqrt {1 + \Lambda ^2C_1}\)/Λ(z+C2)|1/(1+Λ2C1)], where am(u|m) is a Jacobi amplitude function with the elliptic modulus m and the elliptic integral of the first kind u. Especially, u is regarded as arc length of the unit ellipse, defined as u = F(φ, m) = \({\int}_0^\varphi {r(\theta ,m)d\theta }\) where r is radius of the unit ellipse. And the inverse function of u is Jacobi amplitude: φ(z) = F−1(u, m) = am(u|m). Therefore, in general (m ≠ 0), φ(z) is the nonlinear function whereas φ(z) is the linear function if it is defined with reference to a circle (m = 0). Here, C2 is related to the phase shift along z axis and C1 modulates u and m, respectively. With exchange interaction and anisotropy fixed, DM interaction modulates the reference from a circle to an ellipse. For example, when DM interaction that prefers to be spiral dominates the effective anisotropy that prefers to be uniform, m approaches to zero. Therefore, l = {cos[φ(z)], 0, sin[φ(z)]} is described as the trigonometric function where φ(z) is linearly proportional to z; φ(z) = am(u|0) ~ kz. However, when the DM interaction does not dominate the anisotropy, m is nonzero, so that φ(z) becomes the nonlinear function and l is defined with Jacobi elliptic function; cos[φ(z)] = cos[am(u|m)] ≡ cn[u|m] and sin[φ(z)] = sin[am(u|m)] ≡ sn[u|m]. Also, the nontrivial states have been classified into a quasi-uniformed state and a pure spiral state by the critical DM energy, where dy > dc changes a domain wall state into a spiral state30. In our system, dc is derived as dc = 4(ΩKz)1/2/π = 2(JKz)1/2/π from inserting φ(z) = −π/2+2arctan(exp(z+C2)/Λ) into Eq. (1). However, to decrease the anisotropy energies in the confined geometry, the nontrivial states are preferred to be of symmetric (S) or antisymmetric (AS) state for lz depending on the DM energy (see Fig. 2). Each state is characterized by the first condition that is given as φ(z = lw/2) = nπ for the S state or φ(z = lw/2) = (2n + 1)π/2 for the AS state where n is an integer. The second condition becomes Neumann-type boundary condition as Eq. (3a): |dφ/dz|z = 1 or lw = dy/(2Ω) = 2dy/J. Notably, as dy/dc is over ~ 2, φ(z) approaches a linear function φ(z) = am[u|m] ~ kz with wavevector k = 2dy/J. And k is compatible with the edge conditions because it enters into a pure spiral regime or m → 0. For example, φ(z) = am[0.1z|−0.1] ~ 0.11z for dy/dc = 6.5 (See Fig. 2a, S state, red open symbols) and φ(z) = am[0.14z|−0.06] ~ 0.14z for dy/dc = 5 (See Fig. 2a, AS state, blue open symbols). Therefore, l is expressed as a trigonometric function; for example, lz = cos[kz + nπ] or lz = cos[kz + (2n + 1)π/2]. However, when dy/dc goes to zero, φ(z) becomes a nonlinear Jacobi amplitude function, where φ(z) = am[0.02z|−2.47] for dy/dc = 1 and φ(z) = am[0.29(z−101/2)|−1.40] for dy/dc = 1.3, respectively, because DM energy competes with anisotropy energy.

Equilibrium configurations of antiferromagnets in a confined structure. Depending on the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya (DM) interaction, lz = cos(φ) takes a (a) symmetric (S) or (b) antisymmetric (AS) configuration. Here, φ is described as a Jacobi amplitude function φ = am(u|m) with elliptic modulus m that is the solution of the sine-Gordan (SG) equation. The exact solution is obtained with two conditions: 1) φ(lw/2) = π or 0 and 2) dφ/dz = 2dy/J at z = 1 or z = lw where lw is wire length in Néel space. The stationary state is calculated from the Landau Lifshitz Gilbert equation when the time goes to infinity and therefore is the solution of the SG model (solid line). As the DM energy increases, lz becomes a pure spiral configuration of φ = kz with wavevector k = 2dy/J (solid line and open circle for n = 5). However, as the DM energy decreases, there is a deviation between the pure spiral approximation and the SG model (solid line and open circle for n = 2). Here, dc is the critical DM energy where dy > dc changes a domain wall state into a chiral state

Next, we derive the dynamics of the soliton in the pure spiral regime because it provides the information about the potential barrier between two symmetric states. To understand soliton dynamics driven by damping-like SOT, the Landau Lifshitz Gilbert (LLG) equations are derived from Eq. 1 in terms of m and l:

where the effective magnetic field is obtained from the functional derivative of energy density as \(\omega _{\mathrm{m}}/\gamma \equiv {\bf{h}}_{{\bf{eff}}} = - \partial U_{{\mathrm{1D}}}/\partial {\bf{m}} = - a{\bf{m}} - L{\bf{l}}\prime\) and \(\omega _{\mathrm{l}}{\mathrm{/}}\gamma \equiv {\bf{h}}_{{\bf{eff}}} - \partial U_{{\mathrm{1D}}}{\mathrm{/}}\partial {\bf{l}} = A{\bf{l}}\prime\prime + L{\bf{m}}\prime + K_{\mathrm{z}}l_z\widehat {\bf{z}} + \, {\bf{l}}\prime \times {\bf{D}}\), and the damping-like SOTs for m and l are given as \({\Pi}_{{\mathrm{SOT, m}}} = \omega _s\,[{\bf{m}} \times ({\bf{m}} \times {\bf{p}}) + {\bf{l}} \times ({\bf{l}} \times {\bf{p}})]\) and \({\Pi}_{{\mathrm{SOT, l}}} = \omega _s\,[{\bf{m}} \times ({\bf{l}} \times {\bf{p}}) + {\bf{l}} \times ({\bf{m}} \times {\bf{p}})]\), respectively45. γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, p is the unit polarization of the spin current, ωs is the SOT strength with an angular frequency unit, and α is a phenomenological damping constant. The stationary state is calculated from the LLG equation when the time goes to infinity and therefore is the solution of the SG model as shown in Fig. 2.

By taking the cross product of l in Eq. (4a), we obtained the analytical relation between m and l:

To set a trial function for l, we introduced the collective coordinates θ(t) for the dynamic phase and k for the pure spiral soliton profile: φ(z, t) = k(z-(lw + 1)/2) + θ(t), where we arbitrary shift the soliton profile by (lw + 1/2) so that θ(t) represents the phase at center or φ(z = (lw + 1) /2, t) = θ(t). Inserting Eq. (5) into Eq. (4b) and integrating the sublattice number N from N = 1 to N = lw, the soliton equation of motion is derived as:

Equation 6 represents the equation of motion on θ(t), driven by SOT. When SOT with spin polarization of the y axis applies to the antiferromagnetic chain, the soliton phase oscillates with decay as in pendulum. When SOT is strong enough for θ(t) to go over the potential barrier, Ebarrier, the Néel spiral soliton propagates as a wave in medium. Here, Ebarrier is interpreted as \(\Gamma (d_{\mathrm{y}},l_w) = - K_{\mathrm{z}}{\mathrm{sinc}}[2d_{\mathrm{y}}/J(l_w - 1)]\), which is calculated by integrating the third terms of Eq. (6) from θ = nπ to θ = (n + 1)π/2 or \({\int}_{n\pi }^{(n + 1/2)\pi } {\Gamma {\mathrm{sin}}[{\mathrm{2}}\theta ]{\mathrm{d}}\theta } = \Gamma\). As shown in Fig. 3a, this potential barrier modulation effect will be negligible with large dy (or large lw) because Γ(dy, lw) follows the cardinal sine or sinc function. With \(\dot \theta {\mathrm{(0) = 0}}\)and \(\Gamma (d_{\mathrm{y}},l_w) = 0\), the soliton phase propagates with steady state velocity v = ws/α as in domain wall motion driven by SOT. Note that in Fig. 3a, \(E_{{\mathrm{barrier}}}^{{\mathrm{norm}}}\) is calculated from the normalized anisotropy difference between two states in Fig. 3b and is comparable to Г in the pure spiral regime, as shown in Fig. 3a. For example, when dy/dc = 3.5, Γ < 0, θ(∞) would be nπ (S state), which is located at potential minimum; thus, θ(∞) = (n + 1/2)π corresponds to potential maximum (AS state). Therefore, the anisotropy energy difference between the S and AS states are interpreted as Ebarrier. The former is enable us to calculate \(E_{{\mathrm{barrier}}}^{{\mathrm{norm}}}\) in all ranges of DM energies, as shown by the solid line in Fig. 3a, without deriving equations of motion in low DM energy. It is difficult to derive equations of motion for soliton dynamics in cases of low dy/dc because the soliton configurations for the S and AS states consist of different wavepackets [see the Supplementary Note 2 for S and AS states when dy/dc = 1] and there is a deviation between the SG model and the pure spiral model (see Fig. 3a).

Two possible spiral states as a function of Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya (DM) interaction. a The potential barrier that is calculated from \(E_{{\mathrm{barrier}}}^{{\mathrm{norm}}} = E_{{\mathrm{ani}}}^{{\mathrm{S, norm}}} - E_{{\mathrm{ani}}}^{{\mathrm{AS, norm}}}\) in the range of DM energy. Note that when dy/dc » 2, so that the soliton is well-described by the pure spiral configuration lz = cos(kz), \(E_{{\mathrm{barrier}}}^{{\mathrm{norm}}}\) is described as a cardinal sine or sinc function Γnorm, implying that \(E_{{\mathrm{barrier}}}^{{\mathrm{norm}}}\) is negligible with large DM interaction or the long length lw. b The normalized anisotropy energies, \(E_{{\mathrm{ani}}}^{{\mathrm{S, norm}}}\) (symmetric state, S state) and \(E_{{\mathrm{ani}}}^{{\mathrm{AS, norm}}}\) (antisymmetric state, AS state)

Electric-field-induced switching of antiferromagnetic solitons

Now, the electric-field-induced DM interaction and easy-plane anisotropy are considered. Firstly, the anisotropy in Eq. (1) is recast into \({\sum} {E_K} = - K_{\mathrm{eff}}/2({\bf{l}} \cdot \widehat {\bf{z}})^2 - K_{\mathrm{E}}/2({\bf{l}} \cdot \widehat {\bf{y}})^2\) where Keff = Kz + KE. The y component of the easy plane anisotropy does not contribute to the stability of spiral states because of Keff > KE. And we reformulate the easy plane anisotropy energy as a function of dy; for example, if the DM interaction is induced by electric field as like dy = 0.1 J, KE = 0.12J or KE = (dy/J)2J. Now, dc and Λ are as a function of dy; in large dy, Keff ~ KE and dc = 2(JKE)1/2/π = 2dy/π, and \(\Lambda \equiv \sqrt {\Omega /K_{{\mathrm{eff}}}} = \sqrt {J/K_{{\mathrm{eff}}}} /2 = J/(2d_{\mathrm{y}})\sim 0\). It means that in all ranges of dy, the pure spiral configuration is not formed, so that all soliton states are not described as θ(t) because dy/dc < 1.5. However, the S and AS states are calculated numerically using two conditions in SG model (see Fig. 4a, b). The curves of the anisotropy energy and the potential barrier are not derived analytically.

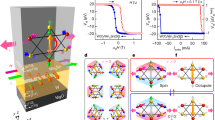

Two possible spiral states determined by Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya (DM) interaction and easy plane anisotropy. a The potential barrier that is calculated from \(E_{{\mathrm{barrier}}}^{{\mathrm{norm}}} = E_{{\mathrm{ani}}}^{{\mathrm{S, norm}}} - E_{{\mathrm{ani}}}^{{\mathrm{AS, norm}}}\) in the range of DM energy. Note that dc are as a function of dy; in large dy, Keff ~ KE and dc = 2(JKE)1/2/π = 2dy/π or dy/dc ~ 1.5 < 2, so that the soliton is not described by the trigonometric function lz = cos(kz). b The normalized anisotropy energies, \(E_{{\mathrm{ani}}}^{{\mathrm{S, norm}}}\) (symmetric state, S state) and \(E_{{\mathrm{ani}}}^{{\mathrm{AS, norm}}}\) (antisymmetric state, AS state). c Schematics for potential depending on the sign of \(E_{{\mathrm{barrier}}}^{{\mathrm{norm}}}\). For example, when \(E_{{\mathrm{barrier}}}^{{\mathrm{norm}}}\) < 0 (or \(E_{{\mathrm{barrier}}}^{{\mathrm{norm}}}\) > 0), the S state (or AS state) is energetically stable with minimum potential energy and the AS state (or S state) is metastable with maximum potential energy

To switch Néel magnetization, our strategy is to modulate potential barriers by controlling ratio dy/J through several steps in which SOT plays a perturbation role. As shown in Fig. 4b, the stationary soliton state is alternatively changed from S to AS states (Ebarrier < 0 to Ebarrier > 0 in Fig. 4a) and then from AS to S states (Ebarrier > 0 to Ebarrier < 0 in Fig. 4a) as the DM energy increases. It completes the Néel arrangement switch in the five steps. In dy/J = 0 (step 1), the uniform antiferromagnetic state along the +z axis is interpreted as an S state with φ(lw/2) = 0. Although the DM energy turns on when dy/J = 0.043 (step 2), the soliton state is not changed because φ(lw/2) = 0 and Ebarrier < 0. When the DM energy is lowered by dy/J = 0.03 (step 3), the S state is unstable because Ebarrier > 0 [see Fig. 4a, AS-state] but, interestingly, does not go into the AS state because it is a metastable state located at a potential maximum (see Fig. 4c), which implies the necessity of small perturbation such as SOT. Therefore, small SOT with unidirectional polarization is necessary for deterministic switching. For example, with a spin current with -py, the soliton would go to an AS state with φ(lw/2) = −1/2π; if spin polarization is of py, AS state would be of φ(lw/2) = 1/2π. Next, in the lowered dy/J = 0.015 (step 4), AS state with φ(lw/2) = −1/2π is required to go S state with φ(lw/2) = −π. Eventually, as DM energy shuts down (step 5), final S state is maintained with θ = −π. All processes are described in Fig. 5a. Note that our solitonic approach allows for simplifying the multistep manipulation of AFMs; because the first two steps and the fourth and fifth steps are in the same state of φ(lw/2) = 0 and φ(lw/2) = −π, so these overlapping steps could be omitted. As shown in Fig. 5b, only the first, third and fifth steps that form the single pulse shape can switch an AFM. In addition, the dy variation from step 1 to step 2 results in spreading and shrinkage of k, i.e., breathing motion due to inertia. However, this motion does not lead to the phase propagation. In addition, it is desirable to consider the field-like torque taking place during working in the real devices. When the magnetic field is applied along arbitrary directions, we can add the Zeeman interaction energy E1D, Z = γħH·m into the total energy density, where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio and ħ is the reduced Plank constant. And Eq. (5) is modified as \({\bf{m}} = \mathop {{\mathbf{l}}}\limits^. \times {\bf{l}}{\boldsymbol{/}}(a\gamma ) - L/a({\bf{l}} \times {\bf{l}}\prime ) \times {\bf{l}}{\boldsymbol{ + }}\gamma \hbar /a{\bf{H}}\)43. If the magnetic field is time-varying, the spiral soliton is driven by field-like torque, ~ dhy/dt46, which is derived after inserting Eq. (5) into Eq. (4b). To suppress field-like torque, the proper strength of SOT should be applied.

Antiferromagnetic switching through Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya (DM) energy changes. DM pulse with a multistep or b single-step profile is applied to induce antiferromagnetic switching, applying weak spin-orbit torque (SOT). Here, electric-field-induced anisotropy is as a function of DM energy. According to potential barrier profiles, the first two steps (dy/J = 0 and 0.043) are stable with a symmetric (S) state. At dy/J = 0.03, the S state is metastable and antisymmetric (AS) becomes a stable state with φ(lw/2) = −1/2π (not 1/2π) due to unidirectional SOT with spin polarization -py. In the fourth and fifth steps (dy/J = 0.015 and 0), the AS state is metastable. Thus, the S state has φ(lw/2) = -π (not π) due to -py. In our switching scenario, the first two steps and the fourth and fifth steps overlap. Therefore, the Néel order could be switched using a single-step function without the second and fourth processes. c Schematic illustration of the Néel configuration for each step

Discussion

Our proposal is dependent of the proper size (lw = 100 or 2N = 200 spins in this calculation) and electric field strength; the necessary electric field can be easily estimated. The characteristic spin–orbit coupling energy ESO of Y3Fe5O12 garnet is 3 eV38 and in transition metal compounds, ESO is typically on the order of ~3 eV. Therefore, the electric field, required to generate dy/J = 0.043 can be estimated as |E|=ESOD/(Jeda) ~ 0.13 V nm−1, where da is the distance between the nearest neighbor magnetic ions and is set to be ~1 nm. To estimate switching power in our work, we suppose simple magnetic pad geometry with thickness t (=5 nm), width w (=60 nm) and pad length (2lw = 200 nm). In the nano-pad with finite w, the two DM vectors (Dy and Dz) are induced, according to Dij ∝ E\(\widehat {\bf{x}}\)×eij, However, the effective anisotropy is along z axis, so that Dz induces magnon splitting in momentum space, not spiral structure along y axis. Possible candiates are MnF247, and YFeO348; all are G-type antiferromagnetic insulators with dominant easy axis and the ratio K/J ~ 10-4. For example, at room temperature, the resistivity of YFeO3 is ρ ~ 106 Ω·m49 and the resistance R = ρt/(wlw) ~ 4.17 × 1011 Ω. Therefore, power W = V2/R ~ 1 pW.

Table 1, we compare the critical switching power estimated from our scenario and SOT or spin transfer torque (STT) devices in the different magnetic tunnel junction structures. The different types of SOT and STT devices is characterized to be of comparable order from ~ μW to ~ mW where SOT devices have the mimimum size as determined by thermal requirements50,51.

As noted in introduction, structural DM interaction strength by asymmetric electrodes could be reduced below dc by engineering its thickness52 or utilizing symmetric electrodes, compared with electric field-induced DM energy. However, the structural DM interaction, weak enough to form a quasi-uniform configuration, reduces the required electric field strength. The above statements are also valid in ferromagnetic counterparts because a ferromagnetic spiral structure is formed by competition between anisotropy sand DM energy and is excited by SOT; in ferromagnetic nanowire, two conditions are given as φ(z = lw/2) = nπ for the S state or φ(z = lw/2) = (2n + 1)π/2 for the AS state and dφ/dz|z=1 or lw = dy/(2A) and dc = 4(AKeff)1/2/π30. Finally, it remains to be seen if there is the electric field effect in different magnetic systems. In magnetic metal system with broken inversion symmetry, the generation mechanisms of DM interaction are two folds: (1) Fert-Levy mechanism53 and (2) Rashba SOC39,40,41,54. In the Fert-Levy mechanism, itinerant electron is mainly exchange-coupled with magnetic ion by RKKY interaction. An additional coupling leads to the DM interaction by scattering of itinerant electron with heavy metal. As aforementioned, the Rashba SOC is related to also itinerant electron in the material with strong SOC. Another electric field induced modulation of anisotropy is reported in the ferromagnetic metal/oxide interface or Ta/ultrathin CoFeB/MgO55, the perpendicular magnetic anisotropy (PMA) is originated from hybridization of oxygen p-orbital and iron d-orbital. In this case, the electric field induces charge redistribution of electron of magnetic metal, resulting in modulation of PMA21,55,56. However, the magnetic insulator is lack of conduction electron and it is hard to expect the charge redistribution by electric field and its related anisotropy modulation.

In conclusion, we investigated spiral dynamics in the presence of DM interaction. In soliton-based spin dynamics, there are two states (symmetric and antisymmetric state) due to competition between anisotropy energy and DM interaction, in which one is stable at a potential minimum, and the other is metastable at a potential maximum, implying that external (or internal) perturbation is necessary for viable applications. Also, all points with potential barrier of zero should be avoided because a single state is not determined energetically. Electric field control of DM interaction is promising for manipulation of AFM because it overcomes the challenging issues of phase matching and overshooting by conventional external torque and does not induce charge-carrying issues such as Joule heating. Finally, by tuning the DM energy and interpreting spiral behavior on soliton picture, we show that the AFM switching can be performed with an effective single-pulse scheme.

Method

Numerical simulations

Numerical simulations (Landau Lifshitz Gilbert model, Eqs. (4a) and (4b)) were conducted from 0 to 500 picosecond (ps) with a 0.1 ps interval using proper parameters for antiferromagnetic insulators with terahertz precessional frequency: J = 41.4 meV (1013 s−1, 10 THz), Kz = 0.0003 J or 4.14 μeV (109 s−1, 1 GHz), ωs = 2π×104 s−1 (≪Kz), α = 0.0008 and lw = 100. The magneto-static interaction is neglected for clear oscillating behavior of phase. The rising and falling times of the time-varying electric field pulse were set to 1 ps so that the oscillating phase does not experience unwanted effects during electric field change.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Sinova, J., Valenzuela, S. O., Wunderlich, J., Back, C. H. & Jungwirth, T. Spin Hall effects. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1213–1260 (2015).

Jungwirth, T., Wunderlich, J. & Olejnik, K. Spin Hall effect devices. Nat. Mater. 11, 382–390 (2012).

Manchon, A., Koo, H. C., Nitta, J., Frolov, S. M. & Duine, R. A. New perspectives for Rashba spin–orbit coupling. Nat. Mater. 14, 871–882 (2015).

Soumyanarayanan, A., Reyren, N., Fert, A. & Panagopoulos, C. Emergent phenomena induced by spin–orbit coupling at surfaces and interfaces. Nature 539, 509–517 (2016).

Miron, I. M. et al. Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection. Nature 476, 189–193 (2011).

Miron, I. M. et al. Current-driven spin torque induced by the Rashba effect in a ferromagnetic metal layer. Nat. Mater. 9, 230–234 (2010).

Liu, L. et al. Spin-torque switching with the giant spin hall effect of tantalum. Science 336, 555–558 (2012).

Kim, J. et al. Layer thickness dependence of the current-induced effective field vector in Ta|CoFeB|MgO. Nat. Mater. 12, 240–245 (2013).

Yu, G. et al. Switching of perpendicular magnetization by spin–orbit torques in the absence of external magnetic fields. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 548–554 (2014).

Fan, Y. et al. Magnetization switching through giant spin–orbit torque in a magnetically doped topological insulator heterostructure. Nat. Mater. 13, 699–704 (2014).

Wang, X., Pauyac, C. O. & Manchon, A. Spin-orbit-coupled transport and spin torque in a ferromagnetic heterostructure. Phys. Rev. B 89, 054405 (2014).

Garello, K. et al. Symmetry and magnitude of spin–orbit torques in ferromagnetic heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 587–593 (2013).

Fan, X. et al. Observation of the nonlocal spin-orbital effective field. Nat. Commun. 4, 1799 (2013).

Fan, Y. et al. Electric-field control of spin–orbit torque in a magnetically doped topological insulator. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 352–359 (2016).

Demasius, K.-U. et al. Enhanced spin–orbit torques by oxygen incorporation in tungsten films. Nat. Commun. 7, 10644 (2016).

Zarzuela, R. & Tserkovnyak, T. Antiferromagnetic textures and dynamics on the surface of a heavy metal. Phys. Rev. B 95, 180402(R) (2017).

Kim, T. H., Grünberg, P., Han, S. H. & Cho, B. K. Ultrafast spin dynamics and switching via spin transfer torque in antiferromagnets with weak ferromagnetism. Sci. Rep. 6, 35077 (2016).

Cheng, R., Daniels, M. W., Zhu, J.-G. & Xiao, D. Ultrafast switching of antiferromagnets via spin-transfer torque. Phys. Rev. B 91, 064423 (2015).

Wadley, P. et al. Electrical switching of an antiferromagnet. Science 351, 587 (2016).

Khymyn, R. et al. Antiferromagnetic THz-frequency Josephson-like oscillator driven by spin current. Sci. Rep. 7, 43705 (2017).

Matsukura, F., Tokura, Y. & Ohno, H. Control of magnetism by electric fields. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 209 (2015).

Balakrishnan, J., Koon, G. K. W., Jaiswal, M., Castro Neto, A. H. & Özyilmaz, B. Colossal enhancement of spin–orbit coupling in weakly hydrogenated graphene. Nat. Phys. 9, 284 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. Room temperature magnetization switching in topological insulator-ferromagnet heterostructures by spin-orbit torques. Nat. Commun. 8, 1364 (2017).

Lee, J. W. et al. Enhanced spin-orbit torque by engineering Pt resistivity in Pt/Co/AlOx structures. Phys. Rev. B 96, 064405 (2017).

Kwak, W.-Y., Kwon, J.-H., Grünberg, P., Han, S. H. & Cho, B. K. Current-induced magnetic switching with spin-orbit torque in an interlayer-coupled junction with a Ta spacer layer. Sci. Rep. 8, 3826 (2018).

Qiu, X. et al. Enhanced spin-orbit torque via modulation of spin current absorption. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 217206 (2016).

Dzyaloshinskii, I. A thermodynamic theory of “weak” ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 4, 241 (1958).

Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91 (1960).

Heinze, S. et al. Spontaneous atomic-scale magnetic skyrmion lattice in two dimensions. Nat. Phys. 7, 713 (2011).

Rohart, S. & Thiaville, A. Skyrmion confinement in ultrathin film nanostructures in the presence of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 88, 184422 (2013).

Emori, S., Bauer, U., Ahn, S., Martinez, E. & Beach, G. S. D. Current-driven dynamics of chiral ferromagnetic domain walls. Nat. Mater. 12, 611 (2013).

Ryu, K.-S., Thomas, L., Yang, S. & Parkin, S. Chiral spin torque at magnetic domain walls. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 527 (2013).

Shiino, T. et al. Antiferromagnetic domain wall motion driven by spin-orbit torques. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 087203 (2016).

Gomonay, O., Jungwirth, T. & Sinova, J. High antiferromagnetic domain wall velocity induced by néel spin-orbit torques. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 017202 (2016).

Martinez, E. et al. Universal chiral-triggered magnetization switching in confined nanodots. Sci. Rep. 5, 10156 (2015).

Chen, W. & Sigrist, M. Dissipationless multiferroic magnonics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 157203 (2015).

Zhang, X., Liu, T., Flatte, M. E. & Tang, H. X. Electric-field coupling to spin waves in a centrosymmetric ferrite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 037202 (2014).

Liu, T. & Vignale, G. Electric control of spin currents and spin-wave logic. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 247203 (2011).

Kim, K.-W., Lee, H.-W., Lee, K.-J. & Stiles, M. D. Chirality from interfacial spin-orbit coupling effects in magnetic bilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 216601 (2013).

Banerjee, S., Rowland, J., Erten, O. & Randeria, M. Enhanced stability of skyrmions in two-dimensional chiral magnets with rashba spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031045 (2014).

Barnes, S. E., Ieda, J. & Maekawa, S. Rashba spin-orbit anisotropy and the electric field control of magnetism. Sci. Rep. 4, 4105 (2013).

Tveten, E. G., Qaiumzadeh, A., Tretiakov, O. A. & Brataas, A. Staggered dynamics in antiferromagnets by collective coordinates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 127208 (2013).

Tveten, E. G., Muller, T., Linder, J. & Brataas, A. Intrinsic magnetization of antiferromagnetic textures. Phys. Rev. B 93, 104408 (2016).

Borisov, A. B. & Kiselev, V. V. Topological defects in incommensurate magnetic and crystal structures and quasi-periodic solutions of the elliptic sine-Gordon equation. Phys. D 31, 49 (1988).

Cheng, R., Xiao, J., Niu, Q. & Brataas, A. Spin pumping and spin-transfer torques in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 057601 (2014).

Kim, T. H., Grüenberg, P., Han, S. H. & Cho, B. K. Field-driven dynamics and time-resolved measurement of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya torque in canted antiferromanet YFeO3. Sci. Rep. 7, 4515 (2016).

Johnson, F. M. & Nkthercot, A. H. J. Antiferromagnetic resonance in MnF2. Phys. Rev. 114, 705 (1959).

White, R. M., Nemanich, R. J. & Herring, C. Light scattering from magnetic excitations in orthoferrites. Phys. Rev. B 25, 1822 (1982).

Chen, F. et al. Room temperature magnetoelectric effect of YFeO3–Y3Fe5O12 ferrite composites. J. Alloy Compd. 656, 465 (2016).

Shi, S., Oum, Y., Aradhya, S. V., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Fast low-current spin-orbit-torque switching of magnetic tunnel junctions through atomic modifications of the free-layer interfaces. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 011002 (2018).

Aradhya, S. V., Rowlands, G. E., Oh, J., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Nanosecond-timescale low energy switch- ing of in-plane magnetic tunnel junctions through dynamic Oersted-field-assisted spin Hall effect. Nano Lett. 16, 5987 (2016).

Cho, J. et al. Thickness dependence of the interfacial Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction in inversion symmetry broken systems. Nat. Commun. 6, 7635 (2015).

Fert, A., Cros, V. & Sampaio, J. Skyrmions on the track. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 152 (2013).

Srivastava, T. et al. Large-voltage tuning of Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interactions: a route toward dynamic control of skyrmion chirality. Nano Lett. 18, 4871 (2018).

Nakamura, K., Akiyama, T., Ito, T., Weinert, M. & Freeman, A. J. Role of an interfacial FeO layer in the electric-field-driven switching of magnetocrystalline anisotropy at the Fe/MgO interface. Phys. Rev. B 81, 220409(R) (2010).

Imamura, H., Nozaki, T., Yuasa, S. & Suzuki, Y. Deterministic magnetization switching by voltage control of magnetic anisotropy and Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction under an in-plane magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Appl. 10, 054039 (2018).

Ikeda, S. et al. A perpendicular-anisotropy CoFeB–MgO magnetic tunnel junction. Nat. Mater. 9, 721 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by GIST Research Institute (GRI) a grant funded by the GIST in 2019 and by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (No. NRF-2015M3A9B8032703, No. NRF-2017R1A2B2008538 and NRF-2018R1A2B6005183)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.K.C. and T.H.K. conceived the project idea and planned the analytical and numerical calculations. T.H.K. performed the analytical and numerical calculations. T.H.K., S.H.H. and B.K.C. analyzed the data. B.K.C. led the work and wrote the manuscript with T.H.K. The results of the theoretical and numerical findings were discussed by all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, T.H., Han, S.H. & Cho, B.K. Chiral-induced switching of antiferromagnet spins in a confined nanowire. Commun Phys 2, 41 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0143-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0143-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.