Abstract

Continuum atomic processes initiated by photons and electrons occurring in a plasma are fundamental in plasma physics, playing a key role in the determination of ionization balance, equation of state, and opacity. Here we propose the notion of a transient space localization of electrons produced during the ionization of atoms immersed in a hot dense plasma, which can significantly modify the fundamental properties of ionization processes. A theoretical formalism is developed to study the wavefunctions of the continuum electrons that takes into consideration the quantum de-coherence caused by coupling with the plasma environment. The method is applied to the photoionization of Fe16+ embedded in hot dense plasmas. We find that the cross section is considerably enhanced compared with the predictions of the existing isolated-atom model, and thereby partly explains the big difference between the measured opacity of Fe plasma and the existing standard models for short wavelengths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

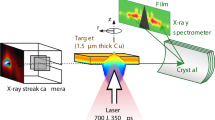

Continuum atomic processes in plasmas such as photoionization and electron-impact ionization, where at least one electron of an atom is ejected into a continuum state, play an important role in the ionization balance dynamics. Recent experimental developments are providing new ways to study the radiative properties of highly ionized and dense plasmas. Bailey et al.1 experimentally measured iron opacity at electron temperatures of 1.9–2.3 million kelvin and electron densities of (0.7–4.0) × 1022 cm−3 at the Z facility2. They observed optical absorptions that are ~30–400% higher than those predicted by current widely used opacity models3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. One evident discrepancy is found at short wavelengths where photoionization dominates the opacity. Enhancement of emission spectra was also observed in solid-density Al plasmas produced by free-electron lasers at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS)13 in the K-shell energy region14. Vinko et al.15 investigated the collisional ionization rates in solid-density Al plasmas created at the LCLS and diagnosed employing a spectroscopic method. They estimated the rate of collisional ionization processes to be several times higher than that predicted by standard semi-empirical models. Very recently, ultrafast electron-impact collisional ionization dynamics is experimentally investigated using resonant core-hole spectroscopy in a solid-density magnesium plasma16. The authors concluded that collisional ionization and recombination cross sections are larger than predicted by several widely used models. These experiments provide valuable information on ionization processes occurring in dense plasma; nevertheless, isolating a particular ionization pathway from other competing transitions is notoriously difficult to measure accurately.

The importance of the basic continuum processes in dense plasmas is that it is the starting point for calculations of physical properties such as the energy balance, charge state distribution, the equation of state, opacity, electronic, and heat conductivity. Extensive investigations have been performed to study plasma screening effects17,18,19 by employing analytical models such as the ion sphere20, Debye-Hückel21, Stewart and Pyatt22, and Ecker and Kröll23. Currently, the commonly used models and codes within the plasma physics community fail to interpret the experimental observations mentioned above. We are still unaware of the physical origin of the discrepancies between the experiment and theory. Since Bailey et al.1 reported their opacity measurement, various theoretical investigations24,25,26,27,28 have been performed trying to improve the opacity models and analyse the associated uncertainties but did not eliminate the difference.

The unsolved issues found in opacity1, continuum emission spectra14, and electron-impact ionization rates15 are closely related to the treatment of the continuum electron in the ionization processes occurred in dense plasmas. In the present state-of-the-art models mentioned above, the continuum electron is treated as fully coherent in space. This should be only a rough approximation without taking account of the de-coherence of the continuum electron.

In this work, we propose a notion of electron transient space localization in continuum processes occurring in hot dense plasma with well-defined electron densities and temperatures. Such electron localizations are caused by the coupling of the continuum electron with the plasma environment. The coupling gives rise to momentum broadening of the continuum electron and hence induces its de-coherence in the processes. We develop a theoretical formalism to include the effects of localization and apply it to photoionization processes of highly charged ion Fe16+ embedded in dense plasmas, taking it as an example. The results show that the cross section is greatly increased compared with the predictions of the existing isolated-atom models. The transient space localization of the continuum electron may also be the physical origin of other phenomena occurring in hot dense plasmas. We suggest that the unexplained experimental observations1,14,15 can be interpreted with the introduction of localization for the continuum electron.

Results

Transient space localization of the continuum electron

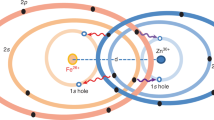

Unlike the ionization of an isolated atom, the continuum electron (here we consider only one continuum electron being ejected for simplification) ejected from a continuum process in a hot dense plasma interacts with the plasma environment. Random collisions of the continuum electron with surrounding particles (ions and free electrons, the latter being the most important) result in a loss of the wave phase and hence the outgoing electron loses coherence in leaving the parent ion. Such environment-induced dephasing of the wavefunction during propagation gives rise to a localized distribution of continuum electrons in space, being more pronounced near the ionization threshold. If the continuum electron is treated as completely free in space, then there is probability to find the electron in the whole physical space. However, the coupling with the environment makes its quantum coherence characteristics being limited to a definite space region. Near the ionization threshold, the energy of the continuum electron is small and hence a small variation of energy or momentum can give rise to a larger effect. On the other hand, the effects of localization are also closely related with the energy distribution of the background electrons in the plasma. Here we use “transient” to specify the short time feature of space localization around the parent ion after ionization. After the ionization event, the electron wave packet can move away due to its nonzero kinetic energy. This dynamical random collision induced transient space localization is similar to Anderson localization29 of electrons scattered randomly by the disorder in solids and to the dynamical localization of Rydberg electrons in a plasma environment30,31. The localization of the latter case is induced by the interaction of the Rydberg electron with free electrons in the plasma, which is similar to the situation in this work.

Momentum broadening of the continuum electron

Elastic and inelastic collisions with a free electron in the plasma result in momentum transfer of the continuum electron. The collisions with plasma electrons give rise to momentum broadening for the continuum electron. The collisions of the bound electrons with the plasma electrons induce an energy broadening of the stationary states, which reduces the lifetime of the bound states. Here we use momentum broadening to characterize the quantum coherence length of the continuum electron. The lifetime is inversely proportional to the energy broadening and likewise the quantum coherence length is inversely proportional to the momentum broadening. In past investigations, the continuum electron is usually assumed to be fully coherent in the whole physical space. In hot dense plasmas, however, the interaction and coupling with the plasma environment ensures the electron is no longer fully coherent in the whole space. Such couplings stop the continuum electron moving to infinity and thus they become localized in a definite region of space.

Figure 1 shows momentum broadening of the continuum electron occurring in a photoionization process of Fe16+ immersed in an iron plasma at a temperature of 180 eV and different electron densities from 4.0 × 1021 to 2.0 × 1023 cm−3. At a given plasma temperature, the momentum broadening increases with increasing plasma density, which means that the effects of electron localization are more pronounced at a denser plasma. With increasing electron energy, momentum broadening rises rapidly from zero to a peak value, and then descends smoothly.

Momentum broadening of the continuum electron. The electron is ejected from the photoionization of Fe16+ embedded in iron plasmas at a temperature of 180.0 eV and electron densities of 4.0 × 1021, 4.0 × 1022, and 2.0 × 1023 cm−3. Atomic units have been used for the half-width at half-maximum of the momentum broadening

In Fig. 2, we show the dependence of the momentum broadening on the plasma temperature with a fixed electron density of 4.0 × 1022 cm−3. We find that the momentum broadening is larger in a hotter plasma. This means that the effects of electron localization are in general more pronounced in a hotter plasma at a given density. This is understandable from the viewpoint of momentum transfer. With increasing temperature, there are more energetic background free electrons which can give rise to a larger momentum transfer to the continuum electron. As a result, the momentum broadening increases with increasing temperature. Note, however, that such an increase will cease at a critical value.

Radial wavefunction of the continuum electron

The momentum broadening means that the momentum and energy of a continuum electron are no longer definite as in a free space but have a range of uncertainty through the exchange of energy with the environment. Near the nucleus, the wavefunctions of continuum electron with different momenta have the same asymptotic behavior and hence they superimpose coherently with definite weights. Here the weight is taken as a Lorentzian distribution \(f\left( {k,k_0} \right) = {\textstyle{{{\mathrm{\Delta }}k{\mathrm{/}}\pi } \over {\left( {k - k_0} \right)^2 + {\mathrm{\Delta }}k^2}}}\) centered at the central momentum k0. We take such a distribution because electron-impact broadening is the dominant mechanism in dense plasma environments, which is a Lorentzian profile when random one-by-one collisions and linear response approximations are used. In the expression, Δk is the half-width at half-maximum (HWHM) of the momentum broadening induced by elastic and inelastic collisions with the plasma electrons.

Figure 3 shows the radial wavefunctions of the electron ejected from the photoionization process hν + 1s22s22p6 1S → 1s22s22p5 2Po + \(e(\epsilon _0s)\) of Fe16+, which was immersed in an iron plasma at a temperature of 180.0 eV and electron densities of 4.0 × 1021, 4.0 × 1022, and 2.0 × 1023 cm−3. The central kinetic energy of the continuum electron is chosen to be 20.0 eV. The radial wavefunctions have been multiplied by the square root of the density of states (DOS) for convenience to simplify the comparison of wavefunctions of isolated ions obtained using the code developed by Gu32. From an inspection of Fig. 3, the amplitude of the wavefunction decreases with the radial distance r from the nucleus, which is different from a free electron that tends to have a constant asymptotic amplitude at r sufficiently large. With increasing density, the amplitude of the wavefunction decreases faster and the continuum electron displays stronger localization. The effect is more pronounced near the ionization threshold. Near the nucleus, however, the amplitude of the wavefunction is enlarged compared with that of an isolated ion. Accordingly, a larger overlap can be found between the wavefunctions of the bound and continuum states that enhances the continuum atomic processes for the embedded ion. The form of the wavefunction introduced in refs. 33,34,35 is similar to that used here.

Radial wavefunction of the continuum electron. The radial wavefunction \(u_{\varepsilon _0\kappa }(r)\) shown in y-axis has been multiplied by the square root of density of states \(\sqrt {D(\varepsilon _0)}\) to have a direct comparison with the result of the corresponding isolated ion. The electron is ejected from the photoionization of hν + 1s22s22p6 1S → 1s22s22p5 2Po + \(e(\epsilon _0s)\) of Fe16+ with a central kinetic energy \(\epsilon _0\) of 20.0 eV and is immersed in iron plasmas at a temperature of 180.0 eV and electron densities of a 4.0 × 1021, b 4.0 × 1022, and c 2.0 × 1023 cm−3. The envelop line denoted by solid dots is given to guide the eyes

Normalized DOS of the continuum electron

From the results presented above, we know that the maximal radial distance that an electron attains is closely related to its energy. Here we introduce the normalized DOS as the ratio of the square root of DOS to the normalization constant of the continuum wavefunction (see Methods for details). From an inspection of results (Fig. 4), one can see that the normalized DOS peaks at some particular electron energy. At the lowest density of 4.0 × 1021 cm−3, it is only slightly larger than unity with a peak value of 1.05 at ~180 eV. At a higher energy above 1000 eV, it tends to be unity, and therefore corresponds to a continuum state in free space. In this instance, the continuum electrons behave as if moving in a potential field of an isolated ion. This may be a natural result at the low-density limit. At the given highest density of 2.0 × 1023 cm−3, however, it deviates from unity by ~150% at an energy of ~400 eV.

Normalized density of states of the continuum electron. The y-axis \(\sqrt {D(\varepsilon _0)} {\mathrm{/}}A\) is a dimensionless quantity, which is defined as the ratio of the square root of density of states \(\sqrt {D(\varepsilon _0)}\) to the normalization constant A (see Eq. (3) in Methods) of the continuum wavefunction. The continuum electron is ejected from the photoionization process hν + 1s22s22p6 1S → 1s22s22p5 2Po + \(e(\epsilon _0s)\) of Fe16+ embedded in iron plasmas at a temperature of 180.0 eV and electron densities of 4.0 × 1021, 4.0 × 1022, and 2.0 × 1023 cm−3

Electron localization-induced enhancement of ionization processes

Transient space localization can significantly modify the ionization processes in a hot dense plasma. As an example, Fig. 5 shows the direct photoionization cross section of the ground level of Fe16+ immersed in a plasma with different electron densities. The cross section of the embedded ion shows a slow increase starting at energies much lower than the ionization threshold of the isolated ion, then a rapid increase to a maximum, and finally a decrease with increasing photon energy. The slow increase of the cross section is a reflection of electron-impact broadening on the ionization threshold. Such behavior is completely different from that of an isolated ion, in that the cross section increases from zero to a definite value at the threshold and then decreases monotonically. The peak cross section increases by 35 and 78% at electron densities of 4.0 × 1022 and 2.0 × 1023 cm−3, respectively, compared with that of the isolated ion model. Zammit, Fursa, and Bray19 showed that the excitation cross section decreases, while the total ionization cross section increases for electron-hydrogen collisions if only the plasma screening effects are considered. However, electron localization-induced enhancement of continuum processes is an additional new effect to those previously considered. Both effects of plasma screening and electron localization have been considered in this work. The former effect usually shows a sharper rise at threshold, while the latter one may enhance the cross section far above the threshold. The photoionization process shows an evident ionization potential depression for the embedded ion. This phenomenon is in agreement with recent experimental measurements36,37,38,39 and theoretical predictions40,41,42.

Enhanced photoionization processes encountered in dense plasmas. The direct photoionization cross sections for hν + 1s22s22p6 1S → 1s22s22p5 2Po + e of Fe16+ embedded at a temperature of 180.0 eV and electron densities of 4.0 × 1021, 4.0 × 1022, and 2.0 × 1023 cm−3 are compared with that of the isolated ion

In Fig. 6 we show the photoionization cross section of Fe16+ immersed in a plasma at an electron density of 4.0 × 1022 cm−3 and different temperatures for the same process as in Fig. 5. We find that the cross section increases more at a higher temperature, yet the ionization potential depression is much less sensitive to the temperature. The variational trend of photoionization cross section with electron density and plasma temperature shown in Figs. 5 and 6 are in qualitatively agreement with the experimental observation in the short wavelength range1.

Striking changes induced by localization may further be seen in the total photoionization cross sections of the ground and excited levels of Fe16+ (Fig. 7). In panel Fig. 7a, both contributions from the direct ionization of 2p and 2s electrons and indirect ionization from the resonant processes have been included to give a more complete picture. The cross section of the isolated ion features a series of resonances 2s → np (n ≥ 6) superimposed on the continuum background. The cross section of isolated ion is in satisfactory agreement with a recent large-scale R-matrix calculation43. For the embedded ion, however, resonances of higher np disappear for the principal quantum number n larger than 10, 7, and 6 at densities of 4.0 × 1021, 4.0 × 1022, and 2.0 × 1023 cm−3, respectively. However, additional resonances of 2s → 5p and 2s → 4p successively show up at the density of 4.0 × 1022 and 2.0 × 1023 cm−3. This shows that the bound states belonging to the configurations of 1s22s2p65p and 1s22s2p64p in the isolated ion Fe16+ have become autoionized states because of plasma screening.

Total photoionization cross sections. a For the ground level 1s22s22p6 1S of Fe16+ including both direct ionization of 2p and 2s electrons and indirect resonant processes embedded in iron plasmas at a temperature of 180.0 eV and electron densities of 4.0 × 1021, 4.0 × 1022, and 2.0 × 1023 cm−3. b For the excited state 1s22s22p53d 1Po of Fe16+, which is assumed to be embedded in an iron plasma at an electron density of 3.0 × 1022 cm−3 and a temperature of 180.0 eV

Electron localization also affects the electron-impact excitation processes, which means a larger electron-impact broadening of the resonance spectral lines of the embedded ion. This effect has been included in the above calculations. Because of the enlarged broadening on the ionization threshold and spectral lines, the edge of the resonance and bound-free absorption was not as clear as in the isolated atom. This feature is shown in Fig. 7b for the total and direct photoionization cross section of the excited state 1s22s22p53d 1Po of Fe16+. With considering electron localization, absorption is greatly increased in the “windows” between the lines of the embedded ion. On one hand, direct photoionization greatly enhances the absorption in the “windows” by many times in the photon energy range 1200–1300 eV compared with that of an isolated ion. On the other hand, combining contributions of resonances, the cross section is further increased in the photon energy range 800–1200 eV. The pronounced localization effect seen in the photoionization cross sections is expected to solve the discrepancy between experiment and theory found for iron plasma opacity for short wavelengths where the bound-free opacity dominate1. In the longer wavelength range where bound–bound absorption dominates the opacity, electron localization will result in a larger spectral line width, which is also in agreement with the experimental finding. However, other factors such as the modified ionization equilibrium caused by electron localization complicate the problem of bound–bound opacity, which is beyond the scope of the present work.

In the calculations of the spectrum, the sum rule is in principle satisfied for an isolated atom. In a hot dense plasma, the hamiltonian of an embedded atom is no longer a hermitian operator and hence the sum rule is in general invalid for such a dissipative system. In other words, because of the strong coupling between the bound and free electrons in dense plasma, the free electrons in the plasma actually take part in the photon ionization processes of the bound electrons. Therefore, the effective number of the active electrons is more than the active bound electrons. There are more electrons in the plasma participating in the transitions of the embedded atom and hence the sum rule should be modified accordingly.

Discussion

The above analysis of electron localization is discussed from a dynamical point of view. The physics may also be understood as a static multichannel interference. In a dense plasma, there are always free electrons in the local space around an ion. Because there are interactions between the continuum electron during continuum processes and plasma electrons, the energy obtained in the continuum processes may be distributed to the continuum electrons and the correlated free electrons. Each combination of continuum electron state and free-electron states forms a reaction channel. As the energy of the free electrons has a continuous distribution, we therefore have continuously distributed reaction channels with a range of energy uncertainty for the continuum electron. The continuum process is a superposition of these reaction channels and therefore the continuum state is also a superposition of nearby definite energy states within the uncertainty. This multichannel-interference view is similar to the interference associated with multiple scattering in Anderson localization. Nevertheless, the present transient space localization does not mean a zero diffusion normally occurs in Anderson localization because of the nonzero average momentum of the state. Localizations described by a momentum broadening of the continuum state is also closely related to the wave packet concept often used to describe electron dynamics in dense plasma44.

Looking forward, the vital role played by localization in the ionization processes embedded in dense plasmas has far-reaching implications in a variety of disciplines including astrophysics, inertial confinement fusion, and high-energy density physics. First, the transient localization of the continuum electron around the parent ion influence the ionization equilibrium and change the charge state distribution; therefore, they influence the equation of state and the radiative properties of plasma. Second, by taking into consideration localization effects, we expect to better understand the discrepancies between theory and experiment reported in the measurements of opacity, electron-impact ionization rates, and the emission properties of dense plasma. Finally, electron localization modifies the laser–matter interactions, particularly in laser interactions with solids and dense plasma. An enhancement should be more pronounced for direct multi-electron processes, where several continuum electrons are ejected simultaneously45.

Methods

To describe based on theory the ionization processes occurring in a hot dense plasma, one has to take simultaneously the effects of plasma screening and localization of electrons into account. Consider an ion of nuclear number Z with N electrons (N = Z refers to an atom) embedded in a plasma of temperature T and electron density ne. The wavefunctions of both the bound and continuum electrons are obtained by solving the effective single-electron relativistic Dirac equation,

where H0 is the effective single-electron Hamiltonian of the isolated ion, which can be determined by a consistent field method32. The plasma screening potential Venv(r) originates from the interaction with surrounding electrons and ions in the plasma. In general, plasma electrons dominate the screening effect and hence we include only their contributions in this work. We proposed an average screening potential produced by plasma electrons based on the model40

where R0 = \(\left( {{\textstyle{3 \over {4\pi n_i}}}} \right)^{\frac{1}{3}}\) defines a radius of ion sphere. The free-electron density distribution ρ(r) follows the Fermi–Dirac statistics, which is obtained from the ionization equilibrium equation of the plasma. In the theoretical treatment we calculate the Kohn-Sham potential using finite-temperature exchange-correlation functionals of Dharma-Wardana and Taylor46. More choice of finite-temperature exchange-correlation functionals can be found in ref. 47.

For the continuum electron, we further consider the localization effect on the radial wavefunction in addition to the plasma screening. This means that the energy and momentum of the electron are no longer definite as in a free space but have a range of uncertainty arising from energy exchanges with the environment. Hence the radial wavefunction of the electron with a central momentum of k0 can be expressed as a superposition within the uncertainty,

where Pkκ(r) is the energy normalized radial wavefunction of the continuum state determined by solving Eq. (1), which has a definite energy determined by its momentum k, κ is the relativistic angular quantum number, and A a re-normalization constant. f(k, k0) describes the expansion coefficient of Pkκ(r) in the momentum space, which is taken as a Lorentzian distribution \(f\left( {k,k_0} \right) = {\textstyle{{{\mathrm{\Delta }}k{\mathrm{/}}\pi } \over {\left( {k - k_0} \right)^2 + {\mathrm{\Delta }}k^2}}}\). Δk is the HWHM of the momentum broadening induced by elastic and inelastic collisions with plasma electrons. For elastic collisions, the continuum electron with an energy of \(\epsilon\) collides with a free electron of energy E in the plasma, which gives rise to a momentum transfer

where the electron–electron differential scattering cross section \(\left( {{\textstyle{{\mathrm{d}\sigma } \over {\mathrm{d}{\mathrm{\Omega }}}}}} \right)_{cm}\) and the momentum Pcm are calculated in the center-of-mass (cm) system. The contribution from inelastic collisions to the momentum transfer of Δk′ is obtained by the inelastic scattering differential cross section of the final state of the ionization process, where the electron is ejected into a continuum state of higher energy. After averaging the momentum transfer over the energy distribution of plasma electrons g(E) (a Maxwellian distribution for the thermodynamic equilibrium plasma), we obtain the momentum broadening Δk.

We re-normalize the delta-function-normalized wavefunction of the continuum electron to unity over the whole space domain (cf. refs. 33,34,35), that is, the normalization condition is \({\int}_0^\infty \left| {u_{k_0\kappa }(r)} \right|^2{\mathrm{d}}r = 1\). The DOS is determined by \(D\left( {k_0} \right) = {\textstyle{{\mathrm{d}}n_r \over {\mathrm{d}\epsilon _0}}}\). In the interval r − (r + dr) of the radial phase space, the number of quantum states equals \({\mathrm{d}}n_r = k_{\epsilon _0\kappa }(r){\mathrm{d}}r{\mathrm{/}}\pi\) with \(k_{\epsilon _0\kappa }(r)\) being the central momentum of the electron. With increasing electron energy \(\epsilon _0\), additional nodes of the wavefunction appear, which are used to obtain the DOS48.

Data availability

The data that support the figures within this paper and other finding of our study are available from corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bailey, J. E. et al. A higher-than-predicted measurement of iron opacity at solar interior temperatures. Nature 517, 56–59 (2015).

Rochau, G. A. et al. ZAPP: the Z astrophysical plasma properties collaboration. Phys. Plasmas 21, 056308 (2014).

Iglesias, C. A. & Rogers, F. J. Opacities for the solar radiative interior. Astrophys. J. 371, 408–417 (1991).

Seaton, M. J., Yan, Y., Mihalas, D. & Pradhan, A. K. Opacities for stellar envelopes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 266, 805–828 (1994).

Delahaye, F. et al. Updated opacities from the Opacity Project. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 360, 458–464 (2005).

Hansen, S., Bauche, J., Bauche-Arnoult, C. & Gu, M. Hybrid atomic models for spectroscopic plasma diagnostics. High. Energy Density Phys. 3, 109–114 (2007).

Porcherot, Q., Pain, J.-C., Gilleron, F. & Blenski, T. A consistent approach for mixed detailed and statistical calculation of opacities in hot plasmas. High. Energy Density Phys. 7, 234–239 (2011).

Blancard, C., Cosse, Ph & Faussurier, G. Solar mixture opacity calculations using detailed configuration and level accounting treatments. Astrophys. J. 745, 10 (2012).

Colgan, J. et al. Light element opacities from ATOMIC. High. Energy Density Phys. 9, 369–374 (2013).

More, R. M., Hansen, S. T. & Nagayama, T. Opacity from two-photon processes. High. Energy Density Phys. 24, 44–49 (2017).

Zeng, J. L. & Yuan, J. M. Radiative opacity of gold plasmas studied by a detailed level-accounting method. Phys. Rev. E 74, 025401(R) (2006).

Pain, J.-C. A note on the contribution of multi-photon processes to radiative opacity. High. Energy Density Phys. 26, 23–25 (2018).

LCLS Website. Available at http://lcls.slac.stanford.edu/ (Last accessed: 06/12/2018).

Vinko, S. M. et al. Creation and diagnosis of a solid-density plasma with an X-ray free-electron laser. Nature 482, 59–62 (2012).

Vinko, S. M. et al. Investigation of femtosecond collisional ionization rates in a solid-density aluminium plasma. Nat. Commun. 6, 6397 (2015).

van den Berg, Q. Y. et al. Clocking femtosecond collisional dynamics via resonant X-Ray spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 055002 (2018).

Janev, R. K., Zhang, S. B. & Wang, J. G. Review of quantum collision dynamics in Debye plasmas. Matter Radiat. Extrem. 1, 237–248 (2016).

Zhang, S. B., Wang, J. G. & Janev, R. K. Crossover of feshbach resonances to shape-type resonances in electron-hydrogen atom excitation with a screened Coulomb interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 023203 (2010).

Zammit, M. C., Fursa, D. V. & Bray, I. Convergent-close-coupling calculations for excitation and ionization processes of electron-hydrogen collisions in Debye plasmas. Phys. Rev. A. 82, 052705 (2010).

Rozsnyai, B. F. Relativistic Hartree-Fock-Slater calculations for arbitrary temperature and matter density. Phys. Rev. A. 5, 1137 (1972).

Debye, P. & Hückel, E. The theory of electrolytes I. The lowering of the freezing point and related occurrences. Phys. Z. 24, 185–206 (1923).

Stewart, J. C. & Pyatt, K. D. Jr. Lowering of ionization potentials in plasmas. Astrophys. J. 144, 1203–1211 (1966).

Ecker, G. & Kröll, W. Lowering of the ionization energy for a plasma in thermodynamic equilibrium. Phys. Fluids 6, 62–69 (1963).

Fontes, C. J. et al. Relativistic opacities for astrophysical applications. High. Energy Density Phys. 16, 53–59 (2015).

Colgan, J. et al. A new generation of LOS ALAMOS opacity tables. Astrophys. J. 817, 116 (2016).

Pain, J. C. & Gilleron, F. Accounting for highly excited states in detailed opacity calculations. High. Energy Density Phys. 15, 30–42 (2015).

Krief, M., Feigel, A. & Gazit, D. Line broadening and the solar opacity problem. Astrophys. J. 824, 98 (2016).

Iglesias, C. A. & Hansen, S. B. Fe xvii opacity at solar interior conditions. Astrophys. J. 835, 284 (2017).

Anderson, P. W. Absence of diffusion in certain random lattices. Phys. Rev. 109, 1492 (1958).

Yeazell, J. A. & Stroud, C. R. Jr. Rydberg-atom wave packets localized in the angular variables. Phys. Rev. A. 35, 2806 (1987).

Lin, C. L., Gocke, C., Röpke, G. & Reinholz, H. Transition rates for a Rydberg atom surrounded by a plasma. Phys. Rev. A. 93, 042711 (2016).

Gu, M. F. The flexible atomic code. Can. J. Phys. 86, 675–689 (2008).

Gyarmati, B. & Vertse, T. On the normalization of Gamow functions. Nucl. Phys. A. 160, 523–528 (1971).

Humblet, J. & Rosenfeld, L. Theory of nuclear reactions : I. Resonant states and collision matrix. Nucl. Phys. 26, 529–578 (1961).

Zeldovich, Ya. B. On the theory of unstable states. Sov. Phys. JETP 12, 542–548 (1961).

Ciricosta, O. et al. Direct measurements of the ionization potential depression in a dense plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 065002 (2012).

Cho, B. I. et al. Resonant Kα spectroscopy of solid-density aluminum plasmas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 245003 (2012).

Ciricosta, O. et al. Measurements of continuum lowering in solid-density plasmas created from elements and compounds. Nat. Commun. 7, 11713 (2016).

Hoarty, D. J. et al. Observations of the effect of ionization-potential depression in hot dense plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 265003 (2013).

Son, S.-K., Thiele, R., Jurek, Z., Ziaja, B., & Santra, R. Quantum-mechanical calculation of ionization-potential lowering in dense plasmas. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031004 (2014).

Vinko, S. M., Ciricosta, O. & Wark, J. S. Density functional theory calculations of continuum lowering in strongly coupled plasmas. Nat. Commun. 5, 3533 (2014).

Iglesias, C. A. A plea for a reexamination of ionization potential depression measurements. High. Energy Density Phys. 12, 5–11 (2014).

Nahar, S. N. & Pradhan, A. K. Large enhancement in high-energy photoionization of Fe XVII and missing continuum plasma opacity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 235003 (2016).

Su, J. T. & Goddard, W. A. III Excited electron dynamics modeling of warm dense matter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 185003 (2007).

Liu, P. F., Zeng, J. L. & Yuan, J. M. A practical theoretical formalism for atomic multielectron processes: direct multiple ionization by a single auger decay or by impact of a single electron or photon. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 51, 075202 (2018).

Dharma-Wardana, M. W. C. & Taylor, R. Exchange and correlation potentials for finite temperature quantum calculations at intermediate degeneracies. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 14, 629–646 (1981).

Ichimaru, S., Iyetomi, H. & Tanaka, S. Statistical physics of dense plasmas: thermodynamics, transport coefficients and dynamic correlations. Phys. Rep. 149, 91–205 (1987).

Meng, X. J., Zhu, X. R., Tian, M. F., Jiang, M. H. & Wang, Z. G. Free or quasi-free electronic density of states in a confined atom. Chin. Phys. Lett. 22, 310–313 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Science Challenge Project No. TZ2018005, by the National Key R&D Program of China under the grant No. 2017YFA0403202, and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. 11674394.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.Y. and J.L.Z. designed the research and wrote the manuscript. P.F.L., C.G., and Y.H. performed the calculations and plotted the figures.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, P., Gao, C., Hou, Y. et al. Transient space localization of electrons ejected from continuum atomic processes in hot dense plasma. Commun Phys 1, 95 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-018-0093-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-018-0093-5

This article is cited by

-

Electron localization enhanced photon absorption for the missing opacity in solar interior

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.