Abstract

Due to their frequency scaling and long-term coherence, frequency combs at the single-photon level can provide a fascinating platform for developments in quantum technology. Here we demonstrate frequency comb single-photon interferometry in an unheralded manner. We are able to induce coherence by erasing the which-way information of path-entangled photon pairs. The photon pairs are prepared using a dual parametric down-conversion pumped by a highly stable frequency comb laser and an ultra-narrow seed laser. This is conducted at the extremely low-conversion efficiency regime. The unique feature of our quantum interferometer is that the induced one-photon interference of the path-encoded single photons (signal), with multiple frequency components, is observed with a unit visibility without heralding conjugate photons (idler). We demonstrate that quantum information and frequency comb technology can be combined to realize quantum information platforms. We expect this will contribute to the application of quantum information and optical measurements beyond the classical limit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent developments in optical frequency comb (OFC) technology1,2 have led to revolutionary advances in optical frequency metrology3,4,5,6,7,8, atomic spectroscopy9,10, molecular spectroscopy11,12,13,14, and dual-comb spectroscopy15,16. Especially, a number of notable works employing quantum frequency combs, which exhibit multimode-entangled photon states17,18,19,20,21, have sought to prove their usefulness in a diverse range of applications involving continuous variable-entangled photons and discrete multidimensional-entangled photons in quantum information processing22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Quantum frequency combs provide a promising platform for quantum information technology based on time-bin-encoded qubits29,30,31, especially for long-distance quantum communication and cryptography32,33,34,35,36,37, because frequency combs are intrinsically coherent in the time domain and scalable in the frequency domain38,39,40.

Quantum path-entangled photons have also been used for optical measurements beyond the classical limits of conventional spectroscopy, metrology, and imaging41,42,43,44,45. Recently, novel quantum spectroscopy and imaging with undetected photons have been reported46,47,48,49,50,51,52. Experimental schemes based on path-entangled photons use the induced quantum coherence of single (signal) photons generated from two spontaneous parametric down-conversion (SPDC) crystals, where the induced coherence resulted from erasing the which-path information of their conjugate (idler) photons53. The degree of induced coherence for the signal photons has a critical dependence on the degree of which-path information for the idler photons, which is a unique feature of non-classicality. Therefore, by placing an optical material on the idler pathway, the degree of path-indistinguishability for the generated idler photons, which depends on the amplitude and phase change of the transmitted idler field, can be controlled, and consequently the visibility of the interference fringe of the conjugate signal photons can be modulated in an unheralded way. This method utilizing the signal-idler quantum entanglement enables material properties to be measured separately from probing the material via idler photon–matter interaction.

In this paper, we demonstrate experimentally and explain theoretically that, by combining the frequency comb technology and the quantum optical measurement method with undetected photons, frequency comb single-photon interferometry (FC-SPI) is feasible. This shows that the quantum interference of signal single-photon frequency combs can be produced by erasing the which-path information of idler photons by making the idler single-photon-added states indistinguishable. Because the quantum state of FC-SPI has high dimensionality with multiple frequency comb components, we believe that the present work paves the way for single-photon interferometry to be applicable to not only quantum information science, but also quantum metrology through quantum spectroscopy and imaging experiments.

Results

Schematic description of FC-SPI

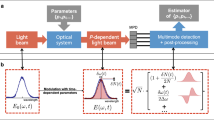

A schematic diagram of the FC-SPI experimental setup is presented in Fig. 1a. A Yb fiber laser frequency comb at 1060 nm is frequency doubled via second-harmonic generation (SHG) to produce an OFC with a center wavelength of 530 nm. Interferometry involves two stimulated parametric down-conversions (StPDCs), where the SHG comb is used as a pump and an additional ultra-narrow linewidth (1 Hz) CW laser at an idler wavelength of 1542 nm is used as a seed beam stimulating multiple frequency comb components at the signal wavelength. Although the PDCs are stimulated by the CW seed beam, the corresponding single-photon emission efficiency is still very low, meaning the multiphoton generation by each StPDC can be safely ignored. The first-order coherence of the signal field is induced by erasing the idler path information. Signal photons (at around 807 nm) are generated from each of the two nonlinear crystals (periodically poled lithium niobate; PPLN) and in turn combined at a beam splitter (BS) placed in front of the spectrometer. Therefore, the double-pathway configuration from the polarizing BS (PBS) separating the SHG comb into two (upper and lower) paths to the beam-combining BS can be considered modified quantum Mach–Zehnder interferometry (a more detailed description is provided in the “Methods).

Schematic representation of the experimental setup and frequency combs. a A frequency comb at λp = 530 nm is generated from a fundamental optical frequency comb at λc = 1060 nm by means of second-harmonic generation. Frequency comb pulse trains pump two separated PPLN crystals and generate a stream of signal and idler photon pairs either in the upper path 1 or in the lower path 2. A monochromatic laser with a linewidth of 1 Hz at 1542 nm is injected into both crystals via two dichroic mirrors (DMs) with a controllable intensity ratio through a variable neutral density (VND) filter. The signal photons are separated from collinearly propagating idler and seed photons by the two DMs after the nonlinear crystals. Only the signal beams are combined by a 50:50 BS placed in front of a spectrometer. The single-photon statistics and interference fringes of the signal photons are detected with either a single-photon counter or an EMCCD camera that is attached to the output of the spectrometer. The signal field interference fringes are measured by modulating the optical path-length differences of the pump beam, the seed beam, and the signal beam paths. b The comb structures of the Yb fiber laser frequency comb, the second-harmonic-generated pump, and the signal field generated by the StPDC in a are schematically shown here

In the low-coupling regime of the well known and widely used SPDC process with a CW laser pump, the probabilistic photon detection of the BS outputs is dominated by single photons from the generated signal field, which are entangled with conjugate idler photons, thus providing a means of heralded single-photon detection. The path-entangled photon pairs from the signal and idler modes exhibit phase coherence in two-photon interference (fourth-order interference in an electric field), as manifested by coincidence counting rate measurements54. However, neither the signal nor the idler field exhibits any one-photon interference (second-order interference in an electric field) patterns. Interestingly, only when the which-path information of the conjugate idler photons is erased does the single-photon coherence of the signal field appear. This can be achieved either by making the two paths of the idler photons indistinguishable by perfectly aligning the two idler beams53,55 or by making the photon statistics of the idler fields indistinguishable by injecting a coherent laser at the idler field frequency55,56,57 without heralding idler detection. The latter scheme is used in our experiment (Fig. 1a); the single-photon coherence of the signal fields on two different paths is induced via the indistinguishability of the two single-photon-added coherent states (SPACS)58 of the idler photons from the two StPDC crystals pumped by the SHG frequency comb light.

In this way, we demonstrate that single-photon interferometry with a quantum frequency comb is feasible without detecting heralded single photons. The quantum state generated by the two StPDC crystals is a path-entangled frequency comb single-photon state (Fig. 1b). The frequency-encoded multidimensional single-photon state can be confirmed by changing one of the two signal paths by means of displacing the retro reflector mirror by the distance traveled by light for the time interval (ΔT) between successive pulses (Fig. 1a). The signal fields generated from the two StPDC crystals pumped by different pump pulses are then overlapped in the BS. In our experiments, we observe a strong interference pattern with a high visibility of about 0.87. This suggests that the coherence time between the single photons passing through either the short or long path is much longer than the pulse-to-pulse time interval (ΔT) and thus the induced coherence of the time-bin photonic state persists longer than the pulse time interval. As shown below, the high visibility of the time-delayed single-photon interference is due to the exceptionally high coherence of the signal optical frequency comb. For this experiment, we constructed highly coherent single-photon frequency combs at the signal wavelengths from the two StPDC crystals arranged in parallel and pumped simultaneously by the same phase-stabilized frequency comb laser and 1-Hz CW seed laser.

We note that the degree of induced single-photon coherence for the signal field can be modulated by the transmission coefficient of the optical sample interacting with one of the injected seed beams (Fig. 1a) because the degree of indistinguishability between the two idler fields generated by the StPDC crystals depends on the optical sample’s spatial or spectral characteristics. Furthermore, the phase information of the idler photon state can be transferred to the signal field state by means of quantum frequency conversion27,28,59,60,61. This is one of the important features of our proposed frequency comb single-photon interferometry involving two StPDC crystals that differentiates it from ordinary Mach–Zehnder single-photon interferometry with just one single-photon source. This double single-photon source configuration allows the concept of quantum imaging and quantum spectroscopy with undetected photons to be implemented by inducing or modulating the intensity and phase imbalances of the two coherent CW seed beam paths.

Theoretical description of optical frequency comb and stimulated PDC

The OFC pump is a train of coherent pulses with carrier frequency ωp = 2πfp. The time interval between neighboring pulses is denoted as ΔT. The carrier-envelop-offset (CEO) phase shift between successive pulses is Δφceo in the time domain. Equivalently, in the frequency domain, the OFC is a multifrequency field completely specified by the frequency interval between neighboring comb teeth that is given by fr = 1/ΔT and a CEO frequency of fceo = frΔφceo/2π62. The simultaneous stabilization of both fr and fceo is required for the OFC. The pulse train of our OFC is linearly polarized and propagates along the z axis. The electric field of the pulse train at z = 0 can then be written as63 (see Supplementary Note 1)

The pump comb frequencies are ωp,n = ωp + 2πnfr for integer n, where the carrier frequency is ωp = 2π(ncfr + fceo) with mode number nc. The nth Fourier coefficient in Eq. (1) is given by \(A_n = \left( 1 / {\Delta T} \right) {\int}_{ - \infty }^\infty {A(t)e^{ - i2\pi n{\kern 1pt} t/\Delta T}{\rm{d}}t}\). Assuming that each pulse envelop is a Gaussian pulse, i.e., \(A(t) = {E}_{0}\exp \left( { - t^2{\mathrm{/}}2\delta ^2} \right)\), where δ is the pulse width, we have \(A_n = {E}_{0}\sqrt {2\pi } \delta {\mathrm{/}}\Delta T\exp ( - 2n^2\pi ^2\delta ^2{\mathrm{/}}\Delta T^2)\). When the input signal photon is in a vacuum state and the input idler photon is in a coherent state with frequency ωi, where the seed laser is a monochromatic CW laser with amplitude α(ωi) at frequency ωi = ωseed, the initial state can be written as \(\left| {\psi (0)} \right\rangle = \left| 0 \right\rangle _{s}\left| {\alpha (\omega _{i})} \right\rangle _{i}\). The quantum state after a single StPDC crystal according to the perturbation theory is then given by

where \({\mathrm F}(\omega _{s,n},\omega _i)\) is a joint spectral function (Supplementary Note 1)64 and \(\left| {\omega _{s,n}} \right\rangle _s\) represents the single-photon Fock state of the nth mode in the signal field with frequency ωs,n = ωp,n − ωi. The quantum state in Eq. (2) clearly shows not only the comb structure of the single-photon signal field, but also the SPACS of the idler field at the injection frequency of ωi. Here, the mode number n in ωs,n of the signal frequency comb or its spectral bandwidth is mainly limited by the phase-matching condition of the nonlinear crystal used.

Theoretical description of FC-SPI

We next describe the working principle behind the single-photon interferometry that is experimentally demonstrated in this study. Two identical StPDC crystals with exactly the same OFC pump and CW seed beams generate photons in the same quantum state described in Eq. (2). The composite quantum state at time t is given by \(\left| {\psi (t)} \right\rangle = \left| {\psi (t)} \right\rangle _1 \otimes \left| {\psi (t)} \right\rangle _2\). It is assumed that the phase-matching condition (Δk ≈ 0) at each StPDC crystal is perfect. In this case, the joint spectral function is approximated as \({\mathrm F}\left( {\omega _s,\omega _i} \right) \approx g_jtA_{j,n}\), where j ∈ {1,2} is the path index of the output fields (Supplementary Note 1). In the low StPDC efficiency regime, which is the case of our experiment, we have |gjtAj,n|2|αj(ωi)|2 << 1 . The composite quantum state can be written up to the first order in the coupling constant as

where \(\hat a_{i_j}^\dagger\) (\(\hat a_{i_j}^{}\)) is the creation (annihilation) operator of the idler photon on the jth path. Here, the probability of generating two pairs of signal-idler photons from a single StPDC crystal is negligible because |g1g2A1,nA2,nt2|2|α1|2|α2|2 <<1.

After combining the signal fields with the BS of our modified quantum Mach–Zehnder interferometer, the single-photon counting rate of the signal field is measured, which is given by \(R_s = \left\langle {\psi (t)} \right|E_s^ - E_s^ + \left| {\psi (t)} \right\rangle\), where \(E_s^ + = \mathop {\sum}\limits_n {e^{i\varphi _{s_1}}\hat a_{s_1}^{}(\omega _{s,n}) + e^{i\varphi _{s_2}}\hat a_{s_2}^{}(\omega _{s,n})}\) and \(\hat a_{s_j}^{}\) (\(\hat a_{s_j}^\dagger\)) is the annihilation (creation) operator of the signal photon on the jth path. We further assume that the pump beams at the two nonlinear crystals have the same amplitudes but different phases, i.e., \(A_{1,n} = \left| {A_n} \right|e^{i\varphi _{p_1}}\) and \(A_{2,n} = \left| {A_n} \right|e^{i\varphi _{p_2}}\). Here, we specifically consider the case where the two seed beams at the two crystals have different phases and amplitudes, i.e., \(\alpha _1(\omega _i) = \left| {\alpha (\omega _i)} \right|e^{i\varphi _{i_1}}\) and \(\alpha _2(\omega _i) = \left| {T(\omega _i)\alpha (\omega _i)} \right|e^{i\varphi _{i_2}}\), where T(ωi) is the amplitude transmission of the optical sample (Fig. 1a). The single-photon counting rate at the photon-number sensitive detector is then found to be

where \(\Delta \varphi _j = \varphi _{j_2} - \varphi _{j_1}\) for j = pump (p), signal (s), and seed (derivation in Supplementary Note 2). Equation (4) shows that the single-photon (second order in the field) interference fringe depends on all the phase differences of the pump, signal, and idler fields in the interferometer. The visibility of the single-photon interference is obtained as

Given the classical limit in which the average photon number of the seed laser is very large, i.e., |α|2 > > 1, the visibility in Eq. (5) reduces to 2|T(ωi)|/(1 + |T(ωi)|2), which shows that the visibility becomes a function of T(ωi) and it is always unity for T(ωi) = 1.

Complementarity relation, indistinguishability, and visibility

In the proposed frequency comb single-photon interferometry, the coherence of the signal fields in the two paths is induced via the indistinguishability of the two conjugate idler fields that are in either an unchanged injected coherent state, \(\left| \alpha \right\rangle\), or the SPACS, \(\hat a_{}^\dagger \left| \alpha \right\rangle\). When the coherent seed laser has a very large average photon number, i.e., |α|2 > > 1, it is not possible to distinguish between the two cases where a single photon is added either to the coherent seed beam in the upper path or to that in the lower path.

To further quantify this argument, let us consider the experimental situation in more detail. For the sake of notational simplicity, let us denote the coherent state and the single-photon state as \(\left| \alpha \right\rangle\) and \(\left| 1 \right\rangle\), respectively. The SPACS of the idler beam after one of the two StPDC crystals is defined as \(\left| {\alpha _j,1} \right\rangle = \hat a_j^\dagger \left| {\alpha _j} \right\rangle /\sqrt {1 + |\alpha _j|^2}\) for j = 1 and 2. The overlap (F) between the two idler states \(\left| {\alpha _1,1} \right\rangle _{i_1}\left| {\alpha _2} \right\rangle _{i_2}\) and \(\left| {\alpha _1} \right\rangle _{i_1}\left| {\alpha _2,1} \right\rangle _{i_2}\) created by the two nonlinear crystals is given by

As both |α1|2 and |α2|2 increase, overlap F approaches unity. Therefore, it becomes in principle impossible to discriminate between a single photon being added to the idler field on the upper path and one being added to the idler field on the lower path. In other words, the critical which-path information of the SPACS in the idler fields is erased due to the indistinguishability within the photon statistics. This is the origin of the induced coherence in the single-photon double-slit experiment implemented using the proposed frequency comb single-photon interferometry with two StPDC crystals working in the quantum mechanical regime.

To examine the relationship between indistinguishability and complementary, in this subsection we assume a monochromatic signal field for notational simplicity. When an optical sample with transmission coefficient T is on the seed beam (upper) path 2 (Fig. 1a), the quantum state of the signal and idler photons in our interferometer can be written as

When the upper seed beam path (Fig. 1a) is blocked, i.e., T = 0, \(\left| {T\alpha ,1} \right\rangle = \left| 1 \right\rangle\) and the overlap F vanishes, which means that the source of a single-photon generation, either from crystal 1 or crystal 2, can be completely distinguishable. Therefore, when T = 0, there is no coherence between the corresponding two signal beams, which leads to zero visibility. Now, consider T = 1, where the two seed beams have equal amplitudes α for both paths. In this case, the first-order interference between the signal single photons from the two independent sources (crystals 1 and 2) would exhibit visibility V = |α|2/(1 + |α|2). For a more general case of a finite T, the visibility is V = 2|T||α|2/(2 + |α|2 + |Tα|2). Because visibility V (wave nature) and distinguishability K (particle nature) should satisfy the complementary relation, i.e., V2 + K2 = 165,66, the distinguishability between the signal photons from the two StPDC crystals is given by

The detailed derivation of Eq. (8) can be found in the “Methods” section. Equation (8) clearly indicates that the signal photon generated by the upper StPDC can be completely distinguishable from that by the lower StPDC when no coherent seed beams are injected into the PDC crystals in the stimulating process.

Signal field interference measurements

To examine the induced coherence of the signal fields, we measured their first-order single-photon interference. The single-photon counting rate given in Eq. (4) predicts perfect interference with V = 1 given that |α|2 > > 1. To adjust the path lengths or equivalently the relative phase differences of the pump, seed, or signal beams in the two paths, three piezo-electric transducers (PZTs) were used (Fig. 1a). To obtain high-contrast interference fringes, we optimized the spatial and temporal modes of the two signal beams and overlapped the single-photon spectra in the two paths, with the corresponding spectrum measured using the spectrometer and EMCCD with an instrument-limited spectral width of 0.1 nm (Supplementary Note 3). Here, the spectrum of each signal beam at around 807.2 nm could be finely tuned by adjusting the phase-matching temperature of the PPLN crystal. To confirm the maximum spectral overlap between the two signal fields, we compared our experimental data with analytic values from the Sellmeier equation for the PPLN crystal (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Unlike previous work that has used CW lasers, the generated signal field also has an optical frequency comb structure with exactly the same repetition rate fr as the pump frequency comb (Supplementary Notes 1 and 4). Therefore, it should be emphasized that the perfect spectral overlap of the signal beams from the two StPDC crystals is critical to the measurement of the single-photon interference fringe whose visibility is close to unity (Supplementary Note 4).

In Fig. 2a, the experimentally measured single-photon counting rate Rs, where the EMCCD exposure time was set to 10 ms, is plotted against the path-length differences Δxp, Δxs, and Δxseed, which are related to the corresponding phase differences as Δφm = 2πΔxm/λm (for m = p, s, and seed). In all three cases, the fringe visibility is close to 1.

One-photon interference fringe and visibility. a The interference fringes are plotted against the pump beam path-length difference (Δxp), signal beam path-length difference (Δxs), and seed beam path-length difference (Δxseed), where the constant background of the detector (EMCCD) is subtracted from the raw data. The solid curves are sinusoidal fit functions. The single-photon count rate is in the order of 104 for a 10-ms exposure time. b The transmission coefficient varies with a variable neutral density (VND) filter placed on one of the seed beam paths. The visibility is obtained from an experimentally measured interference fringe scan with respect to Δxp. The filled squares represent the experimental data and the solid curve represents the theoretical function V = 2 T/(1 + T2). It should be emphasized that the visibilities in all three cases shown in a are as high as 0.99. The error bars represent the standard deviation for several measurements

Stimulated PDC efficiency

To carry out FC-SPI experiments in a very low parametric down-conversion regime where the number of signal photons generated by one pump pulse is much smaller than unity, we attenuated the 530 nm pump power (3.5 mW) and the intensity of the seed beam (4 mW). From Fig. 2a, the single-photon counting rate is about 1 million photons per second with a 10 μm width slit placed in front of the spectrometer (reducing the intensity to 1%). It should be mentioned that the EMCCD with an integration time of 10 ms integrates signals over 2.5 × 106 pulses. Without phase coherence between pulses, the interference fringe should be washed out due to fluctuations in the pulse-to-pulse phase difference Δφceo because the integration time (10 ms) of the detector is much longer than the pulse interval ΔT (4 ns). This clearly shows the absolute necessity of OFC for the pump in our FS-SPI. From the measured single-photon counting rate, the StPDC efficiency of each nonlinear crystal can now be estimated as ηStPDC ≈ 5.2 × 10−10. Consequently, the possibility of each StPDC crystal generating two or more pairs of signal and idler photons can be safely ignored and the photon detection at the BS output is truly dominated by single-photon events. Furthermore, noting that the repetition rate fr of the pump beam is 250.0 MHz, the filling factor per pulse is ~0.02, which means that each generated signal pulse contains 0.02 photons.

In addition, we measure the spontaneous PDC efficiency of our nonlinear crystals and find that ηSPDC ≈ 5.3 × 10−12. Thus, by using the relation between ηStPDC and ηSPDC, i.e., ηStPDC ≈ ηSPDC(|α|2 + 1), the average photon number of the coherent seed beam is found to be |α|2 ≈ 97. This experimentally measured average photon number is consistent with the value calculated by considering the effective seed beam power. Although the injected seed beam power at each arm is about 4 mW (~1016 photons/s), only a fraction (2.1 × 10−3) of the incident CW seed photons contributes to the StPDC process at each nonlinear crystal because the StPDC process most effectively occurs when the CW seed beam and each pump pulse overlap spatially and temporally. Noting that the repetition rate of the pump pulses and the temporal width of each pump pulse are 4 ns (= 1/frep) and 8.4 ps, respectively, the number of effective seed beam photons should be in the order of 1013 photons/s (≈ 1016 photons/s × 8.4 ps × frep). The average photon number of the injected seed beam per unit of down-converted bandwidth can thus be estimated as \(\left| \alpha \right|^2 \approx \frac{{{\rm{Average}}\;{\rm{photon}}\;{\rm{number}}\,{\mathrm{/}}{\rm{s}}}}{{{\rm{bandwidth}}}}\sim 10^2\), where the bandwidth of the idler beam is ~50 GHz, which corresponds to the frequency resolution (0.1 nm) of our spectrometer on the signal beam path. This numerical calculation for the average photon number of the seed beam is in quantitative agreement with our experimentally measured values from the spontaneous and stimulated PDC efficiencies. Thus, the experimentally measured signal field interference in Fig. 2a is in a deep single-photon regime in which the idler which-path information is erased because |α|2 > > 1.

Quantum optical measurement with undetected photons

Although a few different research groups have employed experimental setups similar to ours and have already demonstrated quantum spectroscopy or quantum imaging with undetected photons, the FC-SPI method has not been developed for quantum optical measurement with undetected photons. Here, the visibility V is measured for different values of the amplitude transmission coefficient T of the optical sample placed on one of the seed beam paths, which in turn modulates the distinguishability of the two idler fields after the nonlinear crystals (Fig. 1a). A variable neutral density filter (VND) was used to change T experimentally. Figure 2b depicts the experimentally measured visibility with respect to T. The solid line is the theoretical prediction, i.e., V = 2|T|/(1 + |T|2). The agreement between the experimental data and the theory is very close, clearly indicating that the FC-SPI is a useful quantum optical measurement method for detecting sample transmission coefficient T at the wavelength of undetected idler photons by measuring the visibility of the signal single-photon interference. The observation that the visibility depends only on T is consistent with the fact that the average photon number of the coherent seed beam is much larger than unity, i.e., |α|2 > > 1.

Distinguishability of idler photons with an attenuated CW seed laser

Within the quantum description of the double-StPDC scheme, the visibility of signal one-photon interference is also related to the average photon number of the injected seed beam in idler mode (Eq. 5). This is because the visibility of signal one-photon interference corresponds to the indistinguishability (F) of the idler photons generated by the two NL crystals (Eq. 6). To confirm that this quantum optical description of single-photon interferometry is valid even with a pulsed (frequency comb) pump and a highly coherent seed laser in a significantly low-coupling regime compared to previous work57, we carried out a series of visibility measurements by attenuating the injected seed laser intensity with a variable neutral density (VND) filter for balanced seed beams (T = 1), where the seed beam intensities at the two NL crystals are the same. Our experimentally measured visibilities are quantitatively describable by theory, i.e., V = |α|2/(1 + |α|2), as can be seen in Fig. 3. This indicates that our experiment occurs in a regime that can be only explained using a quantum mechanical description56,57.

One-photon interference visibility with respect to the average photon number of the seed beam (|α|2). a Schematic diagram of the experimental setup that was used to confirm the validity of our quantum optical description of the double-StPDC processes generating signal photons on a single-photon level. The average photon number for the seed beam arriving at the two NL crystals (PPLN) are the same, and they vary with the variable neutral density (VND) filter placed before the 50:50 beam splitter. b The visibility of signal single-photon interference was obtained from the experimentally measured interference fringe with respect to Δxp. The maximum visibility obtained was 0.9, not 1.0, because the signal photons from the two NL crystals could not be completely overlapped spatially in order to achieve a better signal-to-noise ratio. The filled squares represent the experimental data and the solid curve represents the theoretical function V~0.9 × |α|2/(1 + |α|2). The error bars represent the standard deviation for several measurements

Comb structure of generated signal photons

Despite the high visibility of the signal field interference, the nature of the generated signal photons needs to be characterized. More specifically, to confirm that each StPDC generates signal photons with a comb structure in the frequency domain, the spectral width of the resulting signal pulse in the time domain needs to be measured. This first requires the estimation of the temporal width of each pump pulse, which is achieved by monitoring the variation in the interference envelop as a function of the pump beam path difference Δxp (Fig. 4a). The experimental results suggest that the Gaussian pulse width (FWHM) of each pump is 8.4 ps, which results in the optical bandwidth of the pulse being 52.3 GHz. Therefore, there are ~209 modes (comb teeth) in the generated signal frequency comb.

Visibility of one-photon interference with frequency comb-encoded single photons. a Interference visibilities measured experimentally are plotted with respect to Δxp’s, where xp is changed using a micrometer. The maximum visibility approaches unity, when the two signal beams overlap in space and frequency and when the path-length differences of both the pump and the signal beams are zero. From the width of the visibility curve here, the pump pulse width (FWHM) can be estimated as 8.4 ps. b Experimentally measured interference visibilities are plotted with respect to the Δxs’s of the signal beam in the lower path. Here, the lower signal beam path is deliberately made longer than the upper signal beam path by 1.2 m, which corresponds to cΔT, where ΔT = 4 ns and c is the speed of light. This interference confirms that frequency-encoded multidimensional states are generated and maximum visibility is found to be still very high as 0.87. In this figure, the filled squares and the solid line in the right panel represent the experimental data and the fitted Gaussian function, respectively. The error bars represent the standard deviation for several measurements

Here, the linewidth of an individual comb tooth of the signal single-photon frequency combs from each PPLN crystal can be measured using (i) a stronger pump beam than the one used for FC-SPI to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio and (ii) a fast photo-diode detector (see Supplementary Fig. 2). The linewidth of a signal comb tooth is estimated to be about 1 Hz, which is limited by the frequency resolution of the RF spectrum analyzer used here. The measured comb-tooth linewidth (<1 Hz) is almost five orders of magnitude narrower than that of the pump frequency comb, whose linewidth is about 100 kHz. This dramatic narrowing in the linewidth of the generated signal comb teeth is due to the stimulated emission process in the StPDC crystal with the exceptionally narrow (1 Hz) CW seed laser. Therefore, the revival of coherence when the path-length difference is an integer multiple of 1.2 m can be observed in the interference fringe even when the interference pattern is obtained by accumulating over 1 million photons with time delays up to the coherence time (1 s), which is the inverse linewidth (1 Hz) of each signal single-photon frequency comb tooth (Supplementary Note 4).

Long-term coherence of FC-SPI

The path lengths of the two arms in our modified quantum Mach–Zehnder interferometer were adjusted to be the same in the above FC-SPI measurements (see Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Fig. 3). However, to measure the time-bin coherence of the FC-SPI, we deliberately increased the length of the lower signal beam path by 1.2 m. In contrast to the widely used method to generate time-bin photonic states, we did not use beam splitters to split a single pulse from a conventional mode-locked laser into multiple pulses. The pulse trains here were generated by two different PPLN crystals and they propagate along two different paths, which critically differ from the case in which a single pulse is spatially split into two (or multiple) pulses. In our double-StPDC interferometer, the seed laser with a frequency in idler mode is a highly coherent CW beam with an exceptionally narrow (1 Hz) linewidth and the frequency comb pump laser is highly phase-stabilized, with both the repetition rate and the CEO frequency precisely and actively stabilized with reference to the GPS-disciplined Rb atomic clock. Consequently, the pump beam has a phase coherence that is maintained over the entire train of pulses within the 10-ms detector exposure time used in our experiment. Therefore, the single-photon interference between the (n + m)th pulsed signal field from PPLN1 (nonlinear crystal 1) and the nth pulsed signal field from PPLN2 is expected to be observed when the path-length difference is adjusted to be m×cΔT (m is the difference integer). In the present work, we set m = 1 (Fig. 1a) and found that the visibility is still very high, i.e., 0.87 (see Fig. 4b). We attribute this slight reduction in visibility to a non-zero (20 MHz) CEO phase. In measuring the visibility of each signal path difference (Δxs) near m = 1 in Fig. 4b, about 5 × 104 signal photons are detected during each detector exposure period (10 ms) while the pump path difference is periodically modulated. We estimate that, in our extremely low-coupling regime, only one photon can be found approximately every 50 pulses generated from each StPDC crystal. Thus, the filling factor is estimated to be 1/50. When the detection period is as long as 10 ms, it is impossible to measure single-photon interference between the successive pulses with high visibility, e.g., 0.87, if a conventional mode-locked laser is used without the active phase-locking of fceo. This is because the phase-coherence time of a typical mode-locked laser is several orders of magnitude shorter than that of our frequency comb laser.

Furthermore, we demonstrate that the visibility of our single-photon interferometer for varying inter-pulse time differences or path-length differences has a critical dependence on the phase noise (or linewidth) of the generated signal frequency comb teeth. Indeed, the linewidth of the RF beat notes of the generated frequency comb at the signal wavelength exhibits an instrument-limited linewidth of about 1 Hz, which is comparable to that of a highly coherent seed laser (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, we believe that the long-term phase coherence of the StPDC-generated signal photon frequency comb at the single-photon level is a prerequisite for the present FC-SPI. The quantum state of the signal field generated by each PPLN crystal is indeed a single-photon frequency-encoded qudit. The single-photon interference revival shown in Fig. 4b is the key measurement confirming that a single-photon frequency qudit state is generated.

By following Islam et al. (refs67,68), the number of time-bin bases in our system can be increased by adding more nonlinear crystals in a parallel configuration and maintaining path-length differences between signal photons generated from two different crystals to be an integer multiple of cΔT. This is currently under investigation. Nonetheless, it is well known that quantum communication technology requires a robust system for long-distance optical fiber communication with minimized decoherence. Thus, it would be desirable to develop multidimensional qudit technology for quantum communication with high-rate data processing67,68,69. In this regard, it is believed that the frequency-encoded high-dimensional single-photon state demonstrated here could be a useful framework for the future development of fast, robust, secure, and efficient quantum communication technology.

Discussion

In this study we have demonstrated frequency comb single-photon interferometry using a pair of path-entangled photons. Coherence between the two StPDC-generated signal fields can be induced by making their conjugate idler photon statistics indistinguishable, which is in contrast to previously reported quantum spectroscopy46 and imaging47 schemes based on induced coherence via the indistinguishability of idler beam paths. The succinct expression of this generated signal single-photon frequency comb state is \(\left| \psi \right\rangle _s = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{n = 1}^N {C_n\left( {\left| {\omega _{s,n}} \right\rangle _1\left| 0 \right\rangle _2 + C^\prime e^{i\Delta \phi }\left| 0 \right\rangle _1\left| {\omega _{s,n}} \right\rangle _2} \right)}\), which is a frequency-encoded path-entangled single-photon state. Here, we found that the mode number of the signal frequency comb is N ≈ 209 with a frequency of ωs,n and the same frequency interval of ωr as the pump frequency comb. The frequency degrees of freedom of the generated multimode single-photon state could be accessible in quantum information technology if comb-tooth-resolved detection becomes possible in the future, something which can be realized with a frequency comb pump laser with a high repetition rate. In the present work, we have demonstrated that the coherence of generated signal field frequency modes can be verified in the time domain by measuring the single-photon interference revivals with imbalanced (in arm length) FC-SPI.

Because the amplitude and phase of the signal comb state can be modulated by the intensity imbalance and/or the path-length difference of the seed beams, it could be possible to engineer a quantum state of photons remotely with differently colored conjugate photons based on the concept of quantum imaging and quantum spectroscopy with undetected photons46,47,48,49,50. Therefore, we anticipate that our FC-SPI utilizing photons in a frequency-encoded multidimensional qudit state has potential applications in (i) remote quantum measurement with undetected photons, (ii) long-distance remote quantum state engineering by means of frequency conversion, and (iii) quantum information science and technology that requires high dimensionality to increase key rates (refs.23,28,40,67,68 and references therein) and that requires long coherence length and high-dimensional photons for decoherence-free, efficient, and secure communication based on high-rate data processing with the capability of frequency resolving all of the comb teeth.

Here, we also demonstrate that time-bin qubit state measurement is feasible by simply modifying the interferometer setup to have an arm-length difference that is an integer multiple of the pulse-to-pulse separation, which is possible due to the exceptionally long-term phase coherence and intrinsic frequency scalability of the generated signal frequency comb. This long-term phase coherence of a single-photon pulse train can be of use when conducting time-domain double- or multiple-slit experiments with single photons without a Franson interferometer. The high dimensionality of the frequency-encoded photonic state in our FC-SPI can overcome a critical limitation of conventional quantum telecommunication technology: the utilization of a pulsed laser with limited phase stability. Nonetheless, a challenging issue related to the degree of coherence of a signal single-photon frequency comb with a critical dependence on the phase coherence of the pump and seed beams remains to be overcome. Thus, we are currently investigating the effects of the linewidth of a CW seed laser and of the phase noise of a pump frequency comb on the visibility of FC-SPI.

We anticipate that FC-SPI with frequency comb photons at the single-photon level could be useful in a variety of applications in quantum information science because it consists of path-entangled and frequency-encoded qudits that are modulated by undetected photons. In addition, the FC-SPI developed and experimentally demonstrated here can be used to study the fundamental physics of quantum entanglement and to develop novel quantum optical measurement methods with undetected photons, where only the one-photon interference of the signal fields needs to be measured without heralded detections of the entangled idler fields.

Methods

Experimental details

A schematic diagram of our single-photon interferometer is given in Fig. 1a. An optical frequency comb (Menlo Systems) at 1060 nm with a spectral bandwidth of 46 nm is frequency doubled using an LBO crystal. The second-harmonic-generated beam with a center wavelength of 530 nm is used to pump the two StPDC crystals. The repetition rate fr and carrier-offset frequency fceo of the frequency comb are phase-locked to be 250.0 MHz and 20.0 MHz, respectively, with reference to a GPS-disciplined Rb atomic clock. The spectral width of the pump beam at 530 nm, which is estimated to be about 3 nm, is much narrower than that of the injecting OFC beam due to the non-critical phase-matching bandwidth of the LBO crystal at 143 °C and the output power is 7 mW. The pump beam is divided into two paths using a combination of a half-wave plate and PBS. The PDC crystal is periodically poled lithium niobate (PPLN) with type-0 phase-matching, a size of 15 × 7.9 × 0.5 mm3, and a grating width of 7.3 μm. A stream of entangled single-photon pairs, each consisting of a signal photon and an idler photon, are then generated from both crystals through the SPDC process at a phase-matching temperature of 121.5 oC. The emitted SPDC signal photons have a broad bandwidth of over 20 nm.

In the present work, to build a single-photon frequency comb interferometer, we inject a monochromatic laser with a linewidth of 1 Hz (OE waves) along the two paths of the pump beams using two dichroic beam splitters (DM in Fig. 1a). The wavelength of the seed laser is 1542.384 nm. Because the seed beam frequency overlaps with the emission spectrum of the idler photons generated from the PDC crystals, the PDC processes at the two crystals are stimulated. After each StPDC crystal, only the signal field in a single-photon state with a wavelength of 807.2 nm is transmitted through the DM, and the pump and seed beams and generated idler photons are all reflected by the DM. Finally, a beam splitter (BS) combines the signal photons generated from the two StPDC crystals. Single-photon statistics and single-photon interference fringes at both exit ports of the interferometer are measured with a single-photon-sensitive two-dimensional EMCCD camera (Andor Technology) attached to the output port of a spectrometer (Shamrock SR-303i-B, Andor Technology) with a wavelength resolution of 0.1 nm.

Complementary relation

Based on the quantum state in Eq. (7), the reduced density matrix for the signal photon state is written as

where

and

The distinguishability65,66 is then given by

where the normalization factor |C|2 = [(1 + |α|2) + (1 + |Tα|2)]−1. Using Eq. (9), we obtain visibility V and distinguishability K, and confirm the complementary relationship discussed in the main text.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Cundiff, S. T. & Ye, J. Colloquium: femtosecond optical frequency combs. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 325 (2003).

Diddams, S. A. The evolving optical frequency comb. JOSA B 27, B51–B62 (2010).

Hänsch, T. Nobel lecture: passion for precision. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 1297 (2006).

Hall, J. L. Nobel lecture: defining and measuring optical frequencies. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 1279 (2006).

Derevianko, A. & Katori, H. Colloquium: physics of optical lattice clocks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 331 (2011).

Ludlow, A. D., Boyd, M. M., Ye, J., Peik, E. & Schmidt, P. O. Optical atomic clocks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 637 (2015).

Udem, T., Holzwarth, R. & Hänsch, T. W. Optical frequency metrology. Nature 416, 233 (2002).

Diddams, S. A. et al. Direct link between microwave and optical frequencies with a 300 THz femtosecond laser comb. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 5102 (2000).

Udem, T., Reichert, J., Holzwarth, R. & Hänsch, T. Absolute optical frequency measurement of the cesium D 1 line with a mode-locked laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 3568 (1999).

Yoon, T. H., Marian, A., Hall, J. L. & Ye, J. Phase-coherent multilevel two-photon transitions in cold Rb atoms: ultrahigh-resolution spectroscopy via frequency-stabilized femtosecond laser. Phys. Rev. A 63, 011402 (2000).

Diddams, S. A., Hollberg, L. & Mbele, V. Molecular fingerprinting with the resolved modes of a femtosecond laser frequency comb. Nature 445, 627 (2007).

Schliesser, A., Picqué, N. & Hänsch, T. W. Mid-infrared frequency combs. Nat. Photonics 6, 440 (2012).

Mandon, J., Guelachvili, G. & Picqué, N. Fourier transform spectroscopy with a laser frequency comb. Nat. Photonics 3, 99 (2009).

Stowe, M. C. et al. Direct frequency comb spectroscopy. Adv. At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 55, 1-60 (2008).

Coddington, I., Newbury, N. & Swann, W. Dual-comb spectroscopy. Optica 3, 414–426 (2016).

Cho, B., Yoon, T. H. & Cho, M. Dual-comb spectroscopy of molecular electronic transitions in condensed phases. Phys. Rev. A 97, 033831 (2018).

Pinel, O. et al. Generation and characterization of multimode quantum frequency combs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 083601 (2012).

Chen, M., Menicucci, N. C. & Pfister, O. Experimental realization of multipartite entanglement of 60 modes of a quantum optical frequency comb. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 120505 (2014).

Roslund, J., De Araujo, R. M., Jiang, S., Fabre, C. & Treps, N. Wavelength-multiplexed quantum networks with ultrafast frequency combs. Nat. Photonics 8, 109 (2014).

Song, H., Yonezawa, H., Kuntz, K. B., Heurs, M. & Huntington, E. H. Quantum teleportation in space and frequency using entangled pairs of photons from a frequency comb. Phys. Rev. A 90, 042337 (2014).

Gerke, S. et al. Full multipartite entanglement of frequency-comb gaussian states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 050501 (2015).

Cai, Y. et al. Multimode entanglement in reconfigurable graph states using optical frequency combs. Nat. Commun. 8, 15645 (2017).

Xie, Z. et al. Harnessing high-dimensional hyperentanglement through a biphoton frequency comb. Nat. Photonics 9, 536 (2015).

Caspani, L. et al. Multifrequency sources of quantum correlated photon pairs on-chip: a path toward integrated quantum frequency combs. Nanophotonics 5, 351–362 (2016).

Reimer, C. et al. Generation of multiphoton entangled quantum states by means of integrated frequency combs. Science 351, 1176–1180 (2016).

Roztocki, P. et al. Practical system for the generation of pulsed quantum frequency combs. Opt. Express 25, 18940–18949 (2017).

Joshi, C., Farsi, A., Clemmen, S., Ramelow, S. & Gaeta, A. L. Frequency multiplexing for quasi-deterministic heralded single-photon sources. Nat. Commun. 9, 847 (2018).

Manurkar, P. et al. Multidimensional mode-separable frequency conversion for high-speed quantum communication. Optica 3, 1300–1307 (2016).

Brendel, J., Gisin, N., Tittel, W. & Zbinden, H. Pulsed energy-time entangled twin-photon source for quantum communication. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 2594 (1999).

Humphreys, P. C. et al. Linear optical quantum computing in a single spatial mode. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 150501 (2013).

Donohue, J. M., Agnew, M., Lavoie, J. & Resch, K. J. Coherent ultrafast measurement of time-bin encoded photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 153602 (2013).

Gisin, N., Ribordy, G., Tittel, W. & Zbinden, H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 145 (2002).

Marcikic, I., De Riedmatten, H., Tittel, W., Zbinden, H. & Gisin, N. Long-distance teleportation of qubits at telecommunication wavelengths. Nature 421, 509 (2003).

Marcikic, I. et al. Distribution of time-bin entangled qubits over 50 km of optical fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 180502 (2004).

Honjo, T. et al. Long-distance distribution of time-bin entangled photon pairs over 100 km using frequency up-conversion detectors. Opt. Express 15, 13957–13964 (2007).

Honjo, T. et al. Long-distance entanglement-based quantum key distribution over optical fiber. Opt. Express 16, 19118–19126 (2008).

Yin, H.-L. et al. Measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution over a 404 km optical fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 190501 (2016).

Ren, C. & Hofmann, H. F. Simultaneous suppression of time and energy uncertainties in a single-photon frequency-comb state. Phys. Rev. A 89, 053823 (2014).

Lukens, J. M. & Lougovski, P. Frequency-encoded photonic qubits for scalable quantum information processing. Optica 4, 8–16 (2017).

Kues, M. et al. On-chip generation of high-dimensional entangled quantum states and their coherent control. Nature 546, 622 (2017).

Dorfman, K. E., Schlawin, F. & Mukamel, S. Nonlinear optical signals and spectroscopy with quantum light. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 045008 (2016).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 010401 (2006).

Bennink, R. S., Bentley, S. J., Boyd, R. W. & Howell, J. C. Quantum and classical coincidence imaging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 033601 (2004).

D’Angelo, M., Kim, Y.-H., Kulik, S. P. & Shih, Y. Identifying entanglement using quantum ghost interference and imaging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 233601 (2004).

Walborn, S. P., Monken, C., Pádua, S. & Ribeiro, P. S. Spatial correlations in parametric down-conversion. Phys. Rep. 495, 87–139 (2010).

Kalashnikov, D. A., Paterova, A. V., Kulik, S. P. & Krivitsky, L. A. Infrared spectroscopy with visible light. Nat. Photonics 10, 98 (2016).

Lemos, G. B. et al. Quantum imaging with undetected photons. Nature 512, 409 (2014).

Lahiri, M., Lapkiewicz, R., Lemos, G. B. & Zeilinger, A. Theory of quantum imaging with undetected photons. Phys. Rev. A 92, 013832 (2015).

Paterova, A., Yang, H., An, C., Kalashnikov, D. & Krivitsky, L. Measurement of infrared optical constants with visible photons. New J. Phys. 20, 043015 (2018).

Paterova, A. V., Yang, H., An, C., Kalashnikov, D. A. & Krivitsky, L. A. Tunable optical coherence tomography in the infrared range using visible photons. Quantum Sci. Technol. 3, 025008 (2018).

Lee, S. K., Yoon, T. H. & Cho, M. Quantum optical measurements with undetected photons through vacuum field indistinguishability. Sci. Rep. 7, 6558 (2017).

Kolobov, M. I., Giese, E., Lemieux, S., Fickler, R. & Boyd, R. W. Controlling induced coherence for quantum imaging. J. Opt. 19, 054003 (2017).

Zou, X., Wang, L. J. & Mandel, L. Induced coherence and indistinguishability in optical interference. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 318 (1991).

Mandel, L. More Things in Heaven and Earth 460–473 (Springer, Berlin, 1999).

Heuer, A., Menzel, R. & Milonni, P. Complementarity in biphoton generation with stimulated or induced coherence. Phys. Rev. A 92, 033834 (2015).

Ou, Z., Wang, L., Zou, X. & Mandel, L. Coherence in two-photon down-conversion induced by a laser. Phys. Rev. A 41, 1597 (1990).

Wang, L., Zou, X. & Mandel, L. Observation of induced coherence in two-photon downconversion. JOSA B 8, 978–980 (1991).

Zavatta, A., Viciani, S. & Bellini, M. Quantum-to-classical transition with single-photon-added coherent states of light. Science 306, 660–662 (2004).

Kumar, P. Quantum frequency conversion. Opt. Lett. 15, 1476–1478 (1990).

Langford, N. K. et al. Efficient quantum computing using coherent photon conversion. Nature 478, 360 (2011).

Clemmen, S., Farsi, A., Ramelow, S. & Gaeta, A. L. Ramsey interference with single photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 223601 (2016).

Jones, D. J. et al. Carrier-envelope phase control of femtosecond mode-locked lasers and direct optical frequency synthesis. Science 288, 635–639 (2000).

Reichert, J., Holzwarth, R., Udem, T. & Haensch, T. W. Measuring the frequency of light with mode-locked lasers. Opt. Commun. 172, 59–68 (1999).

Keller, T. E. & Rubin, M. H. Theory of two-photon entanglement for spontaneous parametric down-conversion driven by a narrow pump pulse. Phys. Rev. A 56, 1534 (1997).

Jaeger, G., Shimony, A. & Vaidman, L. Two interferometric complementarities. Phys. Rev. A 51, 54 (1995).

Jakob, M. & Bergou, J. A. Quantitative complementarity relations in bipartite systems: entanglement as a physical reality. Opt. Commun. 283, 827–830 (2010).

Martin, A. et al. Quantifying photonic high-dimensional entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 110501 (2017).

Islam, N. T. et al. Robust and stable delay interferometers with application to d-dimensional time-frequency quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. Appl. 7, 044010 (2017).

Islam, N. T., Lim, C. C. W., Cahall, C., Kim, J. & Gauthier, D. J. Provably secure and high-rate quantum key distribution with time-bin qudits. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701491 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. M. Choi for stimulating discussion on single-photon interferometry. This work was supported by IBS-R023-D1

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C. and T.H.Y. conceived this experiment. S.K.L. developed the idea, performed theoretical analysis, experiment, and data analysis. N.S.H. helped the experiment of RF spectrum analysis. All the authors interpreted experimental results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S.K., Han, N.S., Yoon, T.H. et al. Frequency comb single-photon interferometry. Commun Phys 1, 51 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-018-0051-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-018-0051-2

This article is cited by

-

Delayed-Choice Quantum Erasers and the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Paradox

International Journal of Theoretical Physics (2023)

-

Enhancing entanglement detection of quantum optical frequency combs via stimulated emission

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

20 years of developments in optical frequency comb technology and applications

Communications Physics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.