Abstract

Coulomb drag is a favored experimental probe of Coulomb interactions between layers of 2D materials. In reality, these layers display spatial charge density fluctuations known as puddles due to various imperfections. A theoretical formalism for incorporating density inhomogeneity into calculations has however not been developed, making the understanding of experiments difficult. Here, we remedy this by formulating an effective medium theory of drag that applies in all 2D materials. We show that a number of striking features at zero magnetic field in graphene drag experiment which have not been explained by existing literature emerge naturally within this theory. Applying the theory to a phenomenological model of exciton condensation, we show that the expected divergence in drag resistivity is replaced by a peak that diminishes with increasing puddle strength. Given that puddles are ubiquitous in 2D materials, this work will be useful for a wide range of future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

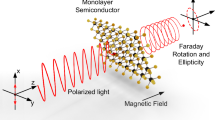

Indirect excitons are quasiparticles that form when an electron from one layer and a hole from another (see Fig. 1) bind together due to Coulomb interaction. Under the right conditions1,2,3,4, these may condense into a superfluid phase5,6 below a critical condensation temperature Tc. This phase is believed to hold great promise for low-power electronics7 and there has been a sustained experimental pursuit of its realization and detection in various two-dimensional material heterostructures8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. The tool of choice for detecting a condensate in these experiments is the Coulomb drag measurement17 which involves driving a current in one (active) electronic layer and measuring the induced potential drop in the other (passive) layer as shown in Fig. 1. The corresponding induced electric field is then divided by the current density in the active layer to yield drag resistivity. Tunneling between the two layers is prevented during this process by a dielectric spacer between them so that the induced electric field is solely due to the interlayer Coulomb interaction. The exciton condensate is then expected to reveal itself as a divergence18 or enhancement19 of the drag resistivity.

Typical experimental Coulomb drag setup. In reality, the two-dimensional layers possess density fluctuations (i.e., puddles) as shown but their effects are largely ignored theoretically, leading to contradiction with experiment. We solve this by generalizing the well-established effective medium theory27,28,29 to the case of Coulomb drag. The scale bar shows local density in units of 1010 cm−2

There exists a large body of theoretical literature on Coulomb drag in 2D systems including a comprehensive review paper20. Most of these theoretical works describe drag between two ideal electronic layers each possessing a uniform charge density. In reality, electronic layers are known to possess charge density fluctations known as puddles21,22,23 as shown in Fig. 1 arising from either charged impurities24 or local strain in the layer25 and there is no known method of eliminating them completely. In spite of this, a controlled way of calculating their effects in actual drag measurements has never been developed, creating difficulties in interpreting drag measurements searching for exciton condensates and other many-body phases.

In this work, we formulate a rigorous framework accounting for puddles in Coulomb drag calculations by generalizing Bruggeman’s effective medium theory (EMT) approximation26,27,28,29 for the first time to the case of Coulomb drag between two inhomogeneous sheets (see Fig. 2). The EMT is a machinery that averages over inhomogeneities in a macroscopically inhomogeneous medium in a self-consistent manner in order to obtain its effective behavior. It has been applied in a wide array of contexts, including magnetoresistance in polycrystalline metals, superconductivity in granular materials and hydrodynamics in suspensions to name but a few29. This work establishes that this powerful machinery may be brought to bear on the Coulomb drag problem and sheds considerable light on existing experimental data. The resulting drag EMT applies in all 2D materials. We illustrate the utility of this formalism through two examples. First, we consider drag between graphene sheets as studied in the experiment by Gorbachev et al.8, focusing only on drag in zero magnetic field. This experiment shows a number of observed features in qualitative contradiction with the predictions of standard theory ignoring puddles, with an unexpected positive peak in drag resistivity at the double neutrality point (DNP) being the one that has received the most attention. The most widely accepted theoretical explanation of the zero-field experimental data invokes a puddle-induced thermoelectric ‘energy drag’30 effect. The work of Song et al.30 however does not consider the non-zero ‘momentum drag’31,32,33,34,35,36 resistivity that will inevitably be induced at the DNP by these same puddles, leaving the question of what exactly causes the peak still open. A second experimental feature that has not been reproduced from theoretical microscopic calculations is the increase of the finite density drag resistivity peaks as a function of temperature. Microscopic calculations of drag in homogeneous samples in fact yield finite density drag peaks that decrease with increasing temperature (see for instance Fig. 8b of Narozhny et al.36). In fact, no theoretical work to date has successfully reproduced both the above experimental features. We show here that once puddles with negative interlayer correlations are taken into account using drag EMT, momentum drag alone is able to reproduce all these features with nearly quantitative agreement. As a second application, we demonstrate using a phenomenological model that puddles cause the divergence in drag resistivity expected upon exciton condensation to be re-normalized to a peak that goes down as the reciprocal of the puddle strength. These two example applications show that puddles must be taken into account in order to understand existing drag experiments on graphene and suggest that they will also play a role in the behavior of drag resistivity in an exciton condensate. Since height corrugations are ubiquitous in 2D materials37 and these in turn lead to puddles25, we expect that the present formalism will be useful for explaining many future 2D Coulomb drag experiments.

Embedding procedure of effective medium theory. An arbitrary ith pair of inclusions in the inhomogeneous layers are each embedded inside an effective medium. The effective in-plane conductivities of the inhomogeneous samples are given by \(\sigma _{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{E}}\) and \(\sigma _{\mathrm{P}}^{\mathrm{E}}\) and the effective drag conductivity by \(\sigma _{\mathrm{D}}^{\mathrm{E}}\)

Results

Model

The derivation of drag EMT parallels that of the usual EMT for inhomogeneous single layer transport (see Supplementary Note 1). Consider the Coulomb drag setup of Fig. 1—two parallel 2D electronic layers with charge density fluctuations separated by some finite distance with an insulating spacer material, with a current flowing through the active layer while the passive layer remains open. We model the inhomogeneities by assuming the active and passive layers are each made up of N inclusions each with its own constant local conductivity, \(\sigma _i^{\mathrm{A}}\) and \(\sigma _i^{\mathrm{P}}\), respectively, where i = 1, …, N. In other words, we model the puddles using a collection of inclusions. These inclusions are assumed to be concentric circles of radius a (i.e., the ith inclusion of the active layer is assumed to lie exactly atop the ith inclusion of the passive). The local drag conductivity \(\sigma _D^i\) corresponding to each ith pair of inclusions is also assumed to be constant. In order for the assumption of constant local conductivities within the inclusions to be justified, the typical conductivity fluctuations within each inclusion must be small. More precisely, \(\left| {\left( {\sigma \left( {\mathbf{r}} \right) - \sigma _i} \right)/\sigma _i} \right| \ll 1\) must be obeyed for all points r within each inclusion, and σi is the average conductivity of the area within the inclusion. Here σi refers generically to the intralayer conductivities, as well as the drag conductivity. We do not make any further assumptions about the nature of the inclusions.

Choosing an arbitrary ith pair of inclusions, one from each layer, we regard them each as being embedded within an effective medium as shown in Fig. 2. The two effective media have within them effective uniform fields \(\vec E_{{\mathrm{A}},0}\) and \(\vec E_{{\mathrm{P}},0}\) representing the total field from all other inclusions, as well as the fields \(\vec E_{{\mathrm{A,S}}}\) and \(\vec E_{{\mathrm{P,S}}}\) arising from the embedded inclusions. Drag conductivity between the two effective media shall be denoted by \(\sigma _{\mathrm{D}}^{\mathrm{E}}\), while the effective media possess effective conductivities \(\sigma _{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{E}}\) and \(\sigma _{\mathrm{P}}^{\mathrm{E}}\), respectively. Within the EMT approximation, \(\sigma _{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{E}}\), \(\sigma _{\mathrm{P}}^{\mathrm{E}}\) and \(\sigma _{\mathrm{D}}^{\mathrm{E}}\) are the intralayer and drag conductivities that will be obtained in experimental measurements on inhomogeneous substrates. We solve for the electric fields inside the inclusions \(\vec E_{\mathrm{A}}^i\) and \(\vec E_{\mathrm{P}}^i\) (see Supplementary Note 2 for details) and substitute them into the EMT self-consistency equations \(\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i f^i\vec E_{\mathrm{A}}^i = \vec E_{{\mathrm{A}},0}\) and \(\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i f^i\vec E_{\mathrm{P}}^i = \vec E_{{\mathrm{P}},0}\) where fi refers to the areal fraction of the ith inclusion relative to the whole layer. These equations enforce the condition within each layer that upon averaging the intra-inclusion field over all inclusions, one should recover the effective uniform field \(\vec E_0\). Note that the effective fields \(\vec E_{{\mathrm{A}},0}\) and \(\vec E_{{\mathrm{P}},0}\) drop out from the equation once the above substitutions are made as is expected since the above condition makes no demands on the specific values of the effective fields. Modeling the densities of the inclusions with continuous probablity distribution functions, we obtain expressions for the effective drag conductivity \(\sigma _{\mathrm{D}}^{\mathrm{E}}\) and in-plane conductivities \(\sigma _{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{E}}\) and \(\sigma _{\mathrm{P}}^{\mathrm{E}}\). The effective drag conductivity is then obtained as

where \(n_{\mathrm{A}}^\prime\) denotes the local charge density in a small region on the active layer and \(n_{\mathrm{P}}^\prime\) denotes the same in a small region directly beneath it on the passive layer, and \(\sigma _{\mathrm{D}}\left( {n_{\mathrm{A}}^\prime ,n_{\mathrm{P}}^\prime } \right)\) denotes the drag conductivity between two sheets of uniform densities \(n_{\mathrm{A}}^\prime\) and \(n_{\mathrm{P}}^\prime\). \(P_{{\mathrm{bi}}}\left( {n_{\mathrm{A}}^\prime ,n_{\mathrm{P}}^\prime } \right)\) is the joint probability distribution of having two such local regions with given charge densities \(\left( {n_{\mathrm{A}}^\prime ,n_P^\prime } \right)\). The effective in-plane conductivities \(\sigma _i^{\mathrm{E}}\) on the other hand are given by the solutions of

where i = A, P henceforth denotes the layer index (instead of inclusion index) and \(\sigma _i\left( {n_i^\prime } \right)\) is the conductivity of layer i at uniform density \(n_i^\prime\). \(P_{{\mathrm{mono}}}\left( {n_i^\prime } \right)\) is the single layer probability density of a point on layer i having charge density \(n_i^\prime\). This is the well-known effective conductivity expression from single layer EMT27,28,29. To calculate drag resistivity in the presence of puddles, we take the clean (i.e., puddle-free) conductivities calculated as a function of \(\left( {n_{\mathrm{A}}^\prime ,n_{\mathrm{P}}^\prime } \right)\) and substitute them into the EMT Eqs. (1) and (2). This yields the effective conductivities \(\sigma _{\mathrm{D}}^{\mathrm{E}}\), \(\sigma _{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{E}}\), \(\sigma _{\mathrm{P}}^{\mathrm{E}}\) in the presence of puddles. The latter step may be understood as an effective averaging of the homogeneous drag resistivity over densities in a manner prescribed by electrostatics. Finally, the effective drag resistivity \(\rho _{\mathrm{D}}^{\mathrm{E}}\) is obtained by inserting the effective conductivities into

The above Eqs. (1)–(3) constitute the generalization of Bruggeman’s historic EMT expression26 to the drag problem. We emphasize that they apply to drag between two layers of arbitrary 2D electronic material. Having completed the derivation, let us make some further caveats. First, so long as the inclusion size a is chosen much larger than the electronic mean free path l in both layers, one may assume the intralayer and drag conductivities \(\sigma _i\left( {n_i^\prime } \right)\) and \(\sigma _{\mathrm{D}}\left( {n_{\mathrm{A}}^\prime ,n_{\mathrm{P}}^\prime } \right)\) are the same as those derived assuming infinite samples (i.e., no finite size effects). Second, we have ignored the drag effect between neighboring inclusions (i.e., the ith inclusion in each layer has a Coulomb drag effect on only the ith inclusion of the other layer and has no effect on other inclusions). This is again justified provided that \(a \gg l\) in both layers. Last, the above derivation assumes that transport is dominated by scattering within the inclusions instead of across the boundaries, thus ignoring scattering processes at the boundaries of the inclusions. We note that an earlier work38 has shown that the above conditions are satisfied in graphene.

The probability distributions Pmono and Pbi are characterized by the average layer densities nA,P, the root mean square density fluctuations \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{A,P}}}\), and the interlayer correlation coefficient η which ranges between −1 for perfect negative correlation of puddles and 1 for perfect positive correlation. The last three quantities \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{\mathrm{A}}\), \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{\mathrm{P}}\) and η are parameters of the theory. The \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{A,P}}}\) values are typically extracted from experimentally obtained intralayer conductivities using Eqs. (2). In the case where a microscopic theory has been formulated for the puddle correlations between the layers39, the latter information is already sufficient to determine the correlation function η as a function of the experimental phase space comprised by average densities (nA, nP) and temperature. In the absence of a microscopic theory for puddle correlations, η may be extracted from experiment using a single slice of drag resistivity in density space (nA, nP) at fixed temperature and a second slice of drag measured as a function of temperature at fixed density (preferably low density since correlations weaken with increasing temperature). This leaves the rest of the large parameter space available for independent fit parameter-free verification of the theory. The drag EMT formalism may be used as a probe of the depth and the correlations of puddle fluctuations in future applications of 2D van der Waals heterostructures40.

Drag in graphene

We consider ‘normal’ drag (i.e., without exciton condensation) in graphene layers and show that a number of distinct features observed in the experiment8 can only be explained using drag EMT. For simplicity, we restrict our considerations to temperatures below 200K so that virtual phonon-induced enhancements to the drag resistivity that become noticeable starting at about 150 K41 may be neglected while still maintaining a reasonable level of accuracy.

The microscopic theory in the disorder-scattering dominated regime for drag between graphene layers ignoring charge puddles and considering screened interlayer interactions up to second order has been worked out in several papers31,32,33,34,35,36 and will henceforth be referred to as the standard momentum drag theory or ‘standard’ theory for brevity. We show here that this theory shows striking differences with the experimental data of Gorbachev et al.8 performed on graphene encapsulated in hexagonal boron nitride (hBN). These discrepancies do not imply that standard momentum drag theory31,32,33,34,35,36 is wrong. Instead, they arise because the samples of Gorbachev et al.8 possess significant charge puddle fluctuations whereas the standard theory applies to spatially homogeneous systems.

We note that theories for Coulomb drag extending into the carrier-carrier collision dominated (i.e., hydrodynamic) limit have also been developed42,43,44,45. We focus here on the disorder-dominated regime and begin by using the standard theory31,32,33,34,35,36 (see Methods for detailed expressions) to calculate the drag resistivity ρD of graphene encapsulated in hBN. We take into account enhancements to ρD due to random dielectric inhomogeneity46 known to occur in the encapsulating hBN substrate47. The particular device studied in Fig. 3a of Gorbachev et al.8 displays dielectric inhomogeneity enhancement by a factor of about 3.6 based on a fit to the experiment (see details in Methods) and we denote the enhanced drag resistivity as \(\tilde \rho _{\mathrm{D}} \equiv 3.6\rho _{\mathrm{D}}\). We note that this work may be modified to include various effects such as dielectric spatial anisotropy41 and frequency dependence34.

Standard theoretical drag resistivity compared against experiment. a Drag resistivity calculated along the the line of oppositely matched densities, assuming puddle-free samples. b Drag resistivity from the experiment of Gorbachev et al.8. c Drag resistivity calculated as a function of layer densities at T = 70K. d Contour lines for the plot in c. Contour lines are drawn every 0.5 Ω from ±1 Ω to ±3 Ω. Interlayer spacing d = 9 nm throughout. Scale bars represent \(\tilde \rho _{\rm{D}}\) in units of Ω

In Fig. 3a, we plot drag resistivity \(\tilde \rho _{\mathrm{D}}\) calculated using standard theory as a function of oppositely matched layer densities at several temperatures. These curves compared to the experiment of Gorbachev et al8. shown in Fig. 3b show qualitative differences in addition to a general quantitative disagreement. First, the experiment sees the peaks at finite density (i.e., the ‘outer’ peaks) increase as temperature increases, whereas standard theory predicts that they decrease. Next, a strong positive central peak at the DNP is seen in the experiment, while standard theory predicts zero drag due to electron-hole symmetry. Last, standard theory predicts drag resistivity peaks bunched up relatively near the DNP which rapidly decay to zero as density increases. The experiment shows a more smeared out structure with the outer peaks occurring at noticeably higher densities and decaying more slowly to zero. To give a sense of the behavior of drag resistivity throughout density space, we plot in Fig. 3c a color map of \(\tilde \rho _{\mathrm{D}}\) calculated as a function of layer densities. We note that a similar plot results for drag in the hydrodynamic regime43. To demonstrate another difference between standard theory and experiment, Fig. 3d shows the contour lines of \(\tilde \rho _{\mathrm{D}}\) in the density space. Each contour line comes in the form of a triangle with two sides lying almost atop the axes and the third ‘outward’ line being rather concave. Gorbachev et al.8 point out that this disagrees with the contour lines obtained experimentally which take the form of triangles with two sides slightly shifted away from the axes, and with the ‘outward’ line being noticeably straighter (see Fig. 1c and Fig. 5 in the supplementary material of Gorbachev et al.8).

Existing works

Before presenting our drag EMT calculations, it is useful to briefly review existing theoretical literature to place our findings in context. The problem of the central drag peak has drawn three explanations. First, it has been theoretically shown by Schütt et al.43 that a third-order interlayer interaction term gives rise to a nonzero drag resistivity at the DNP. This however cannot be the explanation of the experimental data because third order drag remains finite (see Fig. 3 of Schütt et al.) as temperature goes to zero whereas the peak in experiment8 vanishes in this limit. The more ‘popular’ explanation is the energy drag mechanism30 that gives rise to positive drag at the DNP due to interlayer energy exchange48 in the presence of positively correlated puddles (η > 0) caused by charged impurities (a similar effect is mentioned in Schütt et al.43). Since Song et al.30 neglects the sizable negative contribution of momentum drag in the presence of positively correlated puddles at the DNP while taking them into account only in energy drag, one cannot definitely conclude that the latter is the cause of the central peak.

The last proposed explanation is by Gorbachev et al.8 who argue that local sheet corrugations (known as ripples) give rise to spatially varying potentials which induce puddles25. At the DNP, the oppositely charged electron and hole puddles in the layers attract one another, creating negative interlayer correlations (η < 0) which lead to a positive peak at the DNP since momentum drag between oppositely charged carriers is positive (see upper left and lower right quadrants of Fig. 3c).

Numerical results

Having shown that the zero-field data of Gorbachev et al.8 is still not well understood, we present our drag EMT calculations in Fig. 4. The axes nA and nP refer to the average layer densities deduced from gate voltages or Hall resistivity measurements in experiment. Figure 4a shows drag along the line of oppositely matched densities in the presence of negatively correlated puddles and agrees remarkably well with experiment (see Fig. 3b) while Fig. 4b shows the same but in the presence of positively correlated puddles. The agreement of the experiment with Fig. 4a supports the presence of negatively correlated puddles as argued in Gorbachev et al.8. The experimental increase of the outer peaks with temperature and the drag peaks at the DNP (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for temperature dependence) are both successfully reproduced in Fig. 4a with an almost quantitative level of agreement with experiment. The non-zero drag at the DNP is possible because electron-hole symmetry is broken by the puddles in the presence of nonzero correlations. Puddles also cause the outer peaks to move out to densities where \(\left| {E_{\mathrm{F}}^{(i)}} \right|/\left( {\left| {E_{{\mathrm{F}},{\mathrm{rms}}}^{(i)}} \right| + k_{\mathrm{B}}T} \right) \approx 1\), in agreement with the experiment. This general smearing of the drag resistivity throughout the density space is demonstrated in Fig. 4c. Figure 4d shows the contour lines of drag EMT resistivity calculated as a function of nA and nP. The previously concave contour lines have straightened and the other lines have moved away from the axes, in agreement with experiments8,9 (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

Effective medium theory graphene drag calculations. a and b show calculations of the effective drag assuming negatively and positively correlated puddles, respectively, with \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{\mathrm{A,P}} = 6 \times {10}^{10}{\,\mathrm{cm}}^{ - 2}\) in both cases. a uses η in Eq. (16) while b uses the same but with the sign flipped. c EMT drag resistivity calculated as a function of both layer densities at T = 70 K for the same EMT parameters as a. d Contour lines of the plot in (c). The previously curved parts of the contour lines at low density have straightened out and the isolevels that were previously almost touching the axes have moved away from them due to the density-smearing caused by puddles, in agreement with experiments8,9. Isolevels are drawn every 0.5 Ω from ±1 Ω to ±3 Ω. Interlayer spacing d = 9nm throughout. Scale bars represent \(\tilde \rho _D^{{\mathrm{EMT}}}\) in units of Ω

The above calculations were performed by substituting the standard theory expressions31,32,33,34,35,36 (see Methods section) into the EMT equations (1) and (2) and numerically evaluating the result with the layer densities modeled by the bivariate normal distribution in Eq. (7) with average densities nA, nP and root mean square fluctuations \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{(A)}}},n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{(P)}}}\). We have excluded energy drag in our calculations and discuss this later. As mentioned earlier, \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{A,P}}}\) should be determined from measurements of intralayer conductivity. Since such measurements are not available in the experiment of Gorbachev et al.8, we have chosen \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{A,P}}} =6\times {10}^{10}{\,\mathrm{cm}}^{-2}\) by fitting to the experimental drag resistivities at the outer peaks, where correlations are assumed to be weak so η may be set to zero during this fit. These nrms values are comparable with typical measured density fluctuations in graphene on hBN23,22. In all panels of Fig. 4 with the exception of panel (b), we made use of the negative correlation function η given by Eq. (16). Since there is currently no microscopic theory available for arbitrary interlayer correlations, we used a form of η which we believe to be reasonable. First, η was required to decrease in magnitude with increasing density and temperature since screening (which suppressess correlations) in graphene increases with these two quantities. The functional form of η in Eq. (16) was chosen to satisfy this requirement and its numerical prefactors were obtained by fitting to two slices of drag resistivity in density and temperature parameter space (see Methods for more details on this fitting procedure). Since we have only used three lines in the parameter space of nA, nP and T for our fits, this leaves the rest of the large three-dimensional parameter space for fit parameter-free verification of our predictions. At temperatures \(k_{\mathrm{B}}T < 0.5\left| {E_{{\mathrm{F}},{\mathrm{rms}}}^{\left( {{\mathrm{A,P}}} \right)}} \right|\), we find in our numerics that the outer peaks increase with temperature while at temperatures \(k_{\mathrm{B}}T \gtrsim 0.5\left| {E_{{\mathrm{F}},{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{(A,P)}}}} \right|\), the homogeneous behavior of the outer peaks decreasing with temperature remains unchanged (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Here \(E_{{\mathrm{F}},{\mathrm{rms}}}^{(i)} = \hbar v_{\mathrm{F}}\sqrt {\pi n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{(i)}}\). This suggests that cleaner samples in future will show outer peaks that decrease with increasing temperature. We stress that the temperature trend of the outer peaks depends only on the magnitude of nrms and not on η (see Supplementary Fig. 5 for the uncorrelated η = 0 case).

The above changes from homogeneous behavior are explained by noting that the EMT calculation basically averages (in a manner prescribed by the laws of electrostatics) the homogeneous drag resistivity over density space \(\left( {n_{\mathrm{A}}^\prime ,n_{\mathrm{P}}^\prime } \right)\) with the center of the averaging region given by the average densities (nA, nP) and the size of the averaging region given by the root mean square fluctuations \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{A,P}}}\). In the case of uncorrelated puddles η = 0, the averaging region is circular in shape, while in the case of negatively (positively) correlated puddles η < 0 (η > 0), the averaging region is an ellipse with its major axis parallel to the line \(n_{\mathrm{P}}^\prime = - n_{\mathrm{A}}^\prime\) (\(n_{\mathrm{P}}^\prime = n_{\mathrm{A}}^\prime\)). It is easily verified that at the DNP, negative (positive) correlations involve an average involving mainly regions of positive (negative) drag resistivity (see for instance Fig. 3c). This explains the sign of the drag at DNP in Fig. 4a, b. The change in temperature dependence of the outer peaks occurs because the homogeneous peaks at low temperature are narrower in width (see Fig. 3a) and thus more strongly diminished by the averaging procedure. A more physical way to understand Fig. 4 is to note that drag increases (decreases) with increasing temperature at fixed density in the low (high) temperature regime36. Since the presence of puddles causes the local densities in the layers to saturate in magnitude at a lower bound of about \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{A,P}}}\) (with the relative signs of nA and nP in these local regions given by η), if \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{A,P}}} > \left| {n_{\mathrm{A}}} \right|,\left| {n_{\mathrm{P}}} \right|\), the system can be in the low temperature regime locally (which determines the drag characteristics) even if nA and nP are in the high temperature regime (i.e., \(k_{\mathrm{B}}T > \left| {E_{\mathrm{F}}^{{\mathrm{A,P}}}} \right|\)). This causes the low temperature behavior of increasing with T to occur even at average densities that are low relative to temperature. As temperature goes to high values where \(k_{\mathrm{B}}T \gg \left| {E_{{\mathrm{F}},{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{(A,P)}}}} \right|\), drag in this \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{A,P}}} > \left| {n_{\mathrm{A}}} \right|,\left| {n_{\mathrm{P}}} \right|\) regime goes to zero everywhere with increasing temperature because all local regions are in the high temperature regime.

We now discuss the implications of our results for the role of energy drag30. The energy drag resistivity values reported in Song et al.30 in fact give contributions to drag resistivity at the DNP that are roughly equal in magnitude but opposite in sign to the central peaks shown in Fig. 4a, b. This implies that momentum and energy drag will cancel each other to give close to zero drag at the DNP, in contradiction with the experiment. There are however reasons suggesting that energy drag (see details in Supplementary Note 4) is far smaller than momentum drag at the DNP and the latter alone causes the large central peak. The fact that our calculations using momentum drag alone agrees well with experiment supports this conclusion (see also Supplementary Fig. 6).

So far, we have used drag EMT to explain features that have already been reported experimentally. We now predict a new unreported feature. Our calculations predict that drag resistivity does not go to zero along the axis lines nA = 0 and nP = 0 in the presence of nonzero interlayer puddle correlations. Instead, there is a transition in the sign of drag as one tunes the average density of one layer while keeping the other fixed at zero. To be specific, we fix average density of the passive layer nP = 0 and tune the average density of the active layer nA from −∞ to +∞ as shown in Fig. 5 while using the negative-valued correlation function η given in Eq. (16). The double sign change occurs because the EMT average in the case of negative correlations involves an average of the homogeneous drag resistivity over a slanted ellipse. Consistent with this, Gorbachev et al.8 report that the lines of zero drag in density space follow “closely but not exactly” the neutrality points of the individual layers (see Fig. 4c and Fig. 5). We note that if interlayer puddle correlations were positive, measuring drag along this same line would result in Fig. 5 multiplied by an overall minus sign.

Puddle-induced sign changes of drag near double neutrality. Here we calculate effective drag resistivity as a function of nA along the line nP = 0 using effective medium theory with negatively correlated puddles. We use the same parameters as in Fig. 4a. We predict this set of crossovers of the sign of drag may be seen in future experiments

Puddles and drag upon exciton condensation

Drag resistivity is expected to jump discontinuously or diverge as temperature approaches Tc18. This occurs because the drag conductivity in Eq. (3) approaches the values of the single layer in-plane conductivities. The exact value of Tc in graphene is a controversial topic49,50, and it is not known whether a finite Tc is even possible. Our objective here is not to discuss this subtle question but to investigate the impact of puddles on drag resistivity in a system where Tc is assumed to be finite (without the need for a magnetic field) and has already been reached. We describe this hypothetical system using the following physically motivated phenomenological expressions. The monolayer conductivity is given by

and the drag conductivity by

Here, i = A, P is the layer index, and \(\sigma _0 = \frac{{e^2}}{h}\), n0 = 1010 cm−2. B, β and \(C \ll B\) are phenomenological coefficients, the values of which can be chosen quite arbitrarily to fit the material being considered. The statements that we make here do not depend on their particular values. The expressions above are chosen to satisfy the following physical requirements. When the layer densities are perfectly matched (i.e., equal in magnitude but opposite in sign) and the passive layer is open, the electric fields in the layers should be equal based on a minimum dissipation premise51, whereas in the case of a short-circuited passive layer with zero electric field, the layers must contain charge currents of equal magnitude in opposite directions. One easily verifies that Eqs. (4) and (5) satisfy these requirements. Whenever the layers have densities of the same sign, the usual non-excitonic drag that is much weaker than excitonic drag is to be expected. This is represented by the second term with \(C \ll B\).

We study the effect of puddles in this model by substituting Eqs. (4) and (5) into the EMT equations and calculating \(\rho _{\mathrm{D}}^{\mathrm{E}}\) as a function of charge density nA = −nP for various \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{\mathrm{A}} = n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{\mathrm{P}}\) in Fig. 6. We have used the particular values B = 5, β = 1 and η = 0 but stress that we find numerically the following statements apply for arbitrary η and all positive β, B and C so long as \(C \ll B\) and \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{A,P}}} \ll \left| {n_{{\mathrm{A,P}}}} \right|\). Figure 6 shows that the infinite drag resistivity at perfectly matched densities gets suppressed by puddles to a finite value that decreases with increasing puddle strength. The inset shows that the magnitude of drag at perfectly matched densities goes inversely as \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^{{\mathrm{A,P}}}\). In actual experiment where several samples of differing quality will typically be studied, a drag resistivity that goes as 1/nrms may be interpreted as a sign of exciton condensation.

Exciton-condensate drag in the presence of puddles. Drag resistivity in a model of exciton condensate is plotted as a function of nA for different puddle strengths \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^A = n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^P \equiv n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}\). nP is held constant at −50 × 1010 cm−2. Interlayer correlation coefficient η = 0 throughout. Inset: ρD at nA = −nP = 50 × 1010 cm−2 as nrms is varied

Discussion

We have generalized the powerful formalism of effective medium theory to the problem of Coulomb drag between 2D materials possessing puddle fluctuations with arbitrary interlayer correlation. Applying it to graphene drag at zero magnetic field reproduces the striking features observed experimentally that have yet to be fully understood8. Our work shows that these features arise due to momentum drag in the presence of negative interlayer puddle correlations.

There is currently strong experimental52,53,54,55 and theoretical56,57 interest in indirect exciton formation in transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructures. Some experimental drag studies along this line have already begun in heterostructures of MoS258, a material in which the existence of puddles has been experimentally verified59,60, Since the drag EMT formalism developed here applies to arbitrary 2D materials, we believe that it will prove important in the understanding of these and future drag experiments.

Several venues of investigation open up following the present work. The drag EMT formalism may be generalized to include finite magnetic fields10 and interlayer thermoelectric effects61 along the lines of earlier theoretical work on single layer graphene thermoelectricity62. The present work and its extensions will also be useful for assessing and designing potential technological devices such as those in Refs15,63.

Methods

Charge density distributions

We model the single layer charge density using a Gaussian distribution,

where ni without the prime superscript denotes the average charge density of layer i set by the external gate voltage. \(n_{{\mathrm{rms}}}^i\) is the root mean square density fluctuation about the average caused by charged impurities or corrugations and quantifies the strength of inhomogeneity in the sample.

We model the double layer distribution using the bivariate normal probability distribution

where the interlayer correlation coefficient η quantifies the charge density fluctuations between the two layers. Mathematically, η is defined by

where the angular brackets refer to averaging over the areas of the two layers. A value of η = 1 (−1) corresponds to perfectly positively (negatively) correlated charge density fluctuations within the two layers, while a value of η = 0 corresponds to uncorrelated fluctuations. All forms of interlayer correlation may be modeled in Eq. (7) by choosing the value of η accordingly.

Graphene conductivity expressions

The drag conductivity σD(nA, nP) between two sheets at uniform densities nA and nP, respectively can be derived diagramatically64,65, or from a Boltzmann equation approach66 as

where T is temperature, and d the interlayer spacer width. V(q, ω,d) is the dynamically screened interlayer Coulomb interaction given by

where the double-layer dielectric function εD is given by

with bare interlayer and intralayer Coulomb potentials \(V_{12}(q,d) = V_{21}(q,d) = 2\pi e^2\exp ( - qd)/\kappa q\) and V11(q) = V22(q) = 2πe2/κq, respectively, where κ is the dielectric constant of the material encapsulating the graphene sheets and d is the interlayer spacing. Πi is the dynamical polarizability of layer i as shown in existing theoretical literature67. Γx refers to the x-component of the nonlinear susceptibility in monolayer graphene,

where we convert charge density to chemical potential using the methods detailed in Supplementary Note 5. We make use of the dimensionless notation,

With this notation, we follow the approach detailed in Narozhny et al.36 to obtain the expressions

where τi is the transport scattering time of layer i, assumed here to be energy-independent. This is done only for computational efficiency. We have performed preliminary numerical checks with energy-dependent scattering time corresponding to charged impurities (as seen for example in Eq. (10) of Hwang et al.68) and found that it makes no qualitative difference to the behavior of drag resistivity. Note that the dimensionless frequency and momenta defined in this work differ from that in Narozhny et al.36 by a factor of 1/2.

The in-plane conductivity of layer i at uniform density ni is given by

where i = A, P, \(D(E) = 2|E|/(\pi \hbar ^2v_F^2)\) is the density of states and f(E) the Fermi function, given by \(f\left( {E,\mu _i} \right) = \left( {\exp \left( {\frac{{E - \mu _i}}{{k_BT}}} \right) + 1} \right)^{ - 1}\). In the case of completely uniform sheets, we have \(\sigma _{\mathrm{D}}^{\mathrm{E}} = \sigma _{\mathrm{D}}\left( {n_{\mathrm{A}},n_{\mathrm{P}}} \right)\) and \(\sigma _{A,P}^E = \sigma _{A,P}\left( {n_{A,P}} \right)\). In the absence of exciton condensation, \(\sigma _{\mathrm{D}} \ll \sigma _{{\mathrm{A,P}}}\), and hence Eq. (3) becomes \(\rho _{\mathrm{D}}^{\mathrm{E}} \approx - \frac{{\sigma _{\mathrm{D}}^{\mathrm{E}}}}{{\sigma _{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{E}}\sigma _{\mathrm{P}}^{\mathrm{E}}}}\), in which case τA,P drop out of the equation and drag resistivity becomes independent of the scattering mechanism. We assume d = 9nm in all our calculations here, corresponding to the sample in Fig. 3(a) of the Manchester experiment8. We assume the dielectric constant of hBN to be κ = 3.569.

Fitting procedure for dielectric enhancement

The dielectric inhomogeneity enhancement factor of 3.6 is obtained by dividing the 130 K drag resistivity seen in the experiment of Gorbachev et al.8 by that predicted by homogeneous momentum drag theory in the high density regime nA = −nP = 6 × 1011 cm−2, where inhomogeneities have a negligible effect on transport.

Fitting procedure for correlation function

The correlation function η used in Fig. 4a, c, d is chosen in the following way. Based on the physical requirement that correlations decrease with increasing density and temperature due to enhanced screening, we consider the following functional form

Here Θ denotes the Heaviside stepfunction. We determine the numerical coefficients by considering two slices of drag resistivity obtained in the experiment. First, we fit our EMT drag resistivity to the behavior of the experimental drag at the DNP as a function of temperature to obtain B = −1 (i.e., negative correlations), C = 0.005 K−1 and T0 = 70 K. Next, we fit to the experimental drag resistivity measured as a function of nA along the line nA = −nP at T = 70 K (see Fig. 3(b)) and obtain D = 0.5 × 1010 cm2. This correlation function gives perfect negative correlation between the layer puddles at low temperature and decreases in magnitude as density and temperature increase, reflecting that screening gets stronger with increasing density and temperature. We note that this fit was performed by trying different functions by hand. It is likely that even better agreement with experiment will be obtained using more rigorous optimization procedures.

Code availability

Codes used to generate the data shown here are available at https://github.com/derekhoyh/Coulomb-drag-EMT.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Min, H., Bistritzer, R., Su, J.-J. & MacDonald, A. H. Room-temperature superfluidity in graphene bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 78, 121401 (2008).

Kharitonov, M. Y. & Efetov, K. B. Excitonic condensation in a double-layer graphene system. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 25, 034004 (2010).

Dell’Anna, L., Perali, A., Covaci, L. & Neilson, D. Using magnetic stripes to stabilize superfluidity in electron-hole double monolayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 92, 220502 (2015).

Su, J.-J. & MacDonald, A. H. Spatially indirect exciton condensate phases in double bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 95, 045416 (2017).

Eisenstein, J. P. & MacDonald, A. H. Bose Einstein condensation of excitons in bilayer electron systems. Nature 432, 691–694 (2004).

Eisenstein, J. Exciton condensation in bilayer quantum Hall systems. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 5, 159–181 (2014).

Banerjee, S. K., Register, L. F., Tutuc, E., Reddy, D. & MacDonald, A. H. Bilayer PseudoSpin Field-Effect Transistor (BiSFET): a proposed new logic device. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 30, 158–160 (2009).

Gorbachev, R. V. et al. Strong Coulomb drag and broken symmetry in double-layer graphene. Nat. Phys. 8, 896–901 (2012).

Kim, S. & Tutuc, E. Coulomb drag and magnetotransport in graphene double layers, solid state communications exploring. Graph. Recent Res. Adv. 152, 1283–1288 (2012).

Titov, M. et al. Giant magnetodrag in graphene at charge neutrality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 166601 (2013).

Lee, K. et al. Giant frictional drag in double bilayer graphene heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 046803 (2016).

Li, J. et al. Negative Coulomb drag in double bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 046802 (2016).

Li, J. I. A., Taniguchi, T., Watanabe, K., Hone, J. & Dean, C. R. Excitonic superfluid phase in double bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 13, 751–755 (2017).

Liu, X., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T., Halperin, B. I. & Kim, P. Quantum Hall drag of exciton condensate in graphene. Nat. Phys. 13, 746–750 (2017).

Hu, J. et al. Coulomb drag and counterflow Seebeck coefficient in bilayer-graphene double layers. Nano Energy 40, 42–48 (2017).

Gamucci, A. et al. Anomalous low-temperature Coulomb drag in graphene-GaAs heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 5, 5824 (2014).

Siciliani de Cumis, U. et al. A complete laboratory for transport studies of electron-hole interactions in GaAs/AlGaAs ambipolar bilayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 072105 (2017).

Mink, M. P., Stoof, H. T. C., Duine, R. A., Polini, M. & Vignale, G. Probing the topological exciton condensate via Coulomb Drag. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 186402 (2012).

Hu, B. Y.-K. Prospecting for the superfluid transition in electron-hole coupled quantum wells using Coulomb Drag. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 820 (2000).

Narozhny, B. & Levchenko, A. Coulomb drag. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 025003 (2016).

Martin, J. et al. Observation of electron-hole puddles in graphene using a scanning single-electron transistor. Nat. Phys. 4, 144–148 (2008).

Xue, J. et al. Scanning tunnelling microscopy and spectroscopy of ultra-flat graphene on hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 10, 282–285 (2011).

Decker, R. et al. Local electronic properties of graphene on a BN substrate via scanning tunneling microscopy. Nano Lett. 11, 2291–2295 (2011).

Adam, S., Hwang, E. H., Galitski, V. M. & Sarma, S. D. A self-consistent theory for graphene transport. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 104, 18392 (2007).

Gibertini, M., Tomadin, A., Guinea, F., Katsnelson, M. I. & Polini, M. Electron-hole puddles in the absence of charged impurities. Phys. Rev. B 85, 201405 (2012).

Bruggeman, D. A. G. Berechung verschiedener physikalischer konstanten von heterogenen substanzen. Ann. Phys. 24, 636–664 (1935).

Landauer, R. AIP Conference Proceedings, Vol. 40 (AIP Publishing, 1978) pp. 2–45.

Stroud, D. The effective medium approximations: some recent developments. Superlattices Microstruct. 23, 567–573 (1998).

Choy, T. C. Effective medium theory: principles and applications. (Oxford University Press, 2016)

Song, J. C. W. & Levitov, L. S. Energy-driven drag at charge neutrality in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 236602 (2012).

Tse, W.-K., Hu, B. Y.-K. & Das Sarma, S. Theory of Coulomb drag in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 76, 081401 (2007).

Peres, N. M. R., Santos, J. M. B. Ld & Neto, A. H. C. Coulomb drag and high-resistivity behavior in double-layer graphene. EPL 95, 18001 (2011).

Hwang, E. H., Sensarma, R. & Sarma, S. Das Coulomb drag in monolayer and bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 84, 245441 (2011).

Carrega, M., Tudorovskiy, T., Principi, A., Katsnelson, M. I. & Polini, M. Theory of Coulomb drag for massless Dirac fermions. New J. Phys. 14, 063033 (2012).

Amorim, B. & Peres, N. M. R. On Coulomb drag in double layer systems. J. Phys. 24, 335602 (2012).

Narozhny, B. N., Titov, M., Gornyi, I. V. & Ostrovsky, P. M. Coulomb drag in graphene: perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 85, 195421 (2012).

Fasolino, A., Los, J. H. & Katsnelson, M. I. Intrinsic ripples in graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 858–861 (2007).

Rossi, E., Adam, S. & Sarma, S. Das Effective medium theory for disordered two-dimensional graphene. Phys. Rev. B 79, 245423 (2009).

Rodriguez-Vega, M., Fischer, J., Das Sarma, S. & Rossi, E. Ground state of graphene heterostructures in the presence of random charged impurities. Phys. Rev. B 90, 035406 (2014).

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Amorim, B., Schiefele, J., Sols, F. & Guinea, F. Coulomb drag in graphene-boron nitride heterostructures: effect of virtual phonon exchange. Phys. Rev. B 86, 125448 (2012).

Lux, J. & Fritz, L. Kinetic theory of Coulomb drag in two monolayers of graphene: from the Dirac point to the Fermi liquid regime. Phys. Rev. B 86, 165446 (2012).

Schütt, M. et al. Coulomb Drag in graphene near the Dirac point. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 026601 (2013).

Apostolov, S. S., Levchenko, A. & Andreev, A. V. Hydrodynamic Coulomb drag of strongly correlated electron liquids. Phys. Rev. B 89, 121104 (2014).

Chen, W., Andreev, A. V. & Levchenko, A. Boltzmann-Langevin theory of Coulomb drag. Phys. Rev. B 91, 245405 (2015).

Badalyan, S. M. & Peeters, F. M. Enhancement of Coulomb drag in double-layer graphene structures by plasmons and dielectric background inhomogeneity. Phys. Rev. B 86, 121405 (2012).

Kim, S. M. et al. Synthesis of large-area multilayer hexagonal boron nitride for high material performance, Nature. Communications 6, 8662 (2015).

Laikhtman, B. & Solomon, P. M. Mutual drag of two- and three-dimensional electron gases in heterostuctures. Phys. Rev. B 41, 9921–9929 (1990).

Abergel, D. S. L., Rodriguez-Vega, M., Rossi, E. & Sarma, S. Das Interlayer excitonic superfluidity in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 88, 235402 (2013).

Lozovik, Y. E., Ogarkov, S. L. & Sokolik, A. A. Condensation of electron-hole pairs in a two-layer graphene system: Correlation effects. Phys. Rev. B 86, 045429 (2012).

Vignale, G. & MacDonald, A. H. Drag in paired electron-hole layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 2786 (1996).

Ceballos, F., Bellus, M. Z., Chiu, H.-Y. & Zhao, H. Ultrafast charge separation and indirect exciton formation in a MoS2-MoSe2 van der Waals heterostructure. ACS Nano 8, 12717 (2014).

Gao, S., Yang, L. & Spataru, C. D. Interlayer coupling and gate-tunable excitons in transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructures. Nano Lett. 17, 7809–7813 (2017).

Miller, B. et al. Long-Lived Direct and Indirect Interlayer Excitons in van der Waals Heterostructures. Nano Lett. 17, 5229–5237 (2017).

Calman, E. V. et al. Indirect excitons in van der Waals heterostructures at room temperature, Nature. Communications 9, 1895 (2018).

Fogler, M. M., Butov, L. V. & Novoselov, K. S. High-temperature superfluidity with indirect excitons in van der Waals heterostructures, Nature. Communications 5, 4555 (2014).

Berman, O. L. & Kezerashvili, R. Y. Superfluidity of dipolar excitons in a transition metal dichalcogenide double layer. Phys. Rev. B 96, 094502 (2017).

M.-K. Joo, et al., Electron-hole pair condensation in Graphene/MoS2 heterointerface. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1711.00606 (2017).

Shin, B. G. et al. Indirect Bandgap Puddles in Monolayer MoS2 by Substrate-Induced Local Strain. Adv. Mater. 28, 9378–9384 (2016).

Borys, N. J. et al. Anomalous Above-Gap Photoexcitations and Optical Signatures of Localized Charge Puddles in Monolayer Molybdenum Disulfide. ACS Nano 11, 2115–2123 (2017).

Lung, F. & Marinescu, D. C. Thermoelectric effect in a bi-layer system. Phys. E: Low.-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 43, 1769–1773 (2011).

Hwang, E. H., Rossi, E. & Sarma, S. Das Theory of thermopower in two-dimensional graphene. Phys. Rev. B 80, 235415 (2009).

Y. Jin, et al., Coulomb drag transistor via graphene/MoS2 heterostructures. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1710.11365 (2017).

Flensberg, K., Hu, B. Y.-K., Jauho, A.-P. & Kinaret, J. M. Linear-response theory of Coulomb drag in coupled electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 52, 14761–14774 (1995).

Kamenev, A. & Oreg, Y. Coulomb drag in normal metals and superconductors: diagrammatic approach. Phys. Rev. B 52, 7516–7527 (1995).

Jauho, A.-P. & Smith, H. Coulomb drag between parallel two-dimensional electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 47, 4420–4428 (1993).

Ramezanali, M. R., Vazifeh, M. M., Asgari, R., Polini, M. & MacDonald, A. H. Finite-temperature screening and the specific heat of doped graphene sheets. J. Phys. A 42, 214015 (2009).

Hwang, E. H. & Sarma, S. Das Screening-induced temperature-dependent transport in two-dimensional graphene. Phys. Rev. B 79, 165404 (2009).

Young, A. F. et al. Electronic compressibility of layer-polarized bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 85, 235458 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge useful discussions with Cory Dean, Enrico Rossi, Eugene Mele, Boris Narozhny, Justin Song, Marco Polini, Martin Rodriguez-Vega, Navneeth Ramakrishnan, and Giovanni Vignale. D.H. also thanks Lim Yu Chen for his work as part of a high school project in developing early versions of the Matlab codes used here. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation Singapore under its fellowship program (NRF-NRFF2012-01) and by the Singapore Ministry of Education and Yale-NUS College through Grant No. R-607-265-01312. B.Y.K.H. acknowledges the Professional Development Leave granted by the University of Akron and the hospitality of the Center for Advanced 2D Materials at the National University of Singapore. The authors also acknowledge the use of the dedicated computational facilities at the Centre for Advanced 2D Materials and the assistance of Miguel Dias Costa in making use of them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Y.H.H. worked out the theory and numerical calculations with the assistance of I.Y., B.Y.-K.H., and S.A. provided advice and guidance in calculations. All authors discussed ideas and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ho, D.Y.H., Yudhistira, I., Hu, B.YK. et al. Theory of Coulomb drag in spatially inhomogeneous 2D materials. Commun Phys 1, 41 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-018-0039-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-018-0039-y

This article is cited by

-

Electrical control of transient formation of electron-hole coexisting system at silicon metal-oxide-semiconductor interfaces

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Study of drag resistivity in dielectric medium with the correlations effect

Applied Physics A (2021)

-

Effect of quasiparticle excitations and exchange-correlation in Coulomb drag in graphene

Communications Physics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.