Abstract

A first-principles density-functional description of the electronic structures of the high-Tc cuprates has remained a long-standing problem since their discovery in 1986, with calculations failing to capture either the insulating (magnetic) state of the pristine compound or the transition from the insulating to metallic state with doping. Here, by taking lanthanum cuprate as an exemplar high-Tc cuprate, we show that the recently developed non-empirical, strongly constrained and appropriately normed density functional accurately describes both the antiferromagnetic insulating ground state of the pristine compound and the metallic state of the doped system. Our study yields new insight into the low-energy spectra of cuprates and opens up a pathway toward wide-ranging first-principles investigations of electronic structures of cuprates and other correlated materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Treatment of the physics of cuprates is fundamentally complicated by the need to model both the insulating and the metallic phases that form when the material is doped. In lanthanum cuprates, for example, the challenge is to model the parent compound La2CuO4 (LCO) as an insulator and the hole-doped system arising with Sr doping [La2−xSrxCuO4 (LSCO)] as a metal. The workhorse of condensed matter physics, Hohenberg–Kohn–Sham DFT1,2 based on the local spin-density approximation (LSDA) exchange-correlation functional fails to capture this transition, as it incorrectly predicts the parent pristine compound to be a metal and severely underestimates the antiferromagnetic (AFM) structure of the compound. The LSDA functional predicts a copper magnetic moment of ≈0.1 μB in LCO3,4,5,6 compared to the observed value of ≈0.5 μB in neutron diffraction experiments7,8. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) improves the situation somewhat9 by predicting a copper magnetic moment of ≈0.2 μB10, but still does not produce the insulating band gap in LCO. Spin-polarized calculations with the Becke-3-Lee-Yang-Parr (B3LYP)11,12,13,14 hybrid functional stabilize the AFM ground state in LCO15, but miss the key transition to the metallic phase with doping, predicting instead an insulating behavior even in the overdoped (metallic) regime16.

These failures have led to the widespread belief that the DFT is fundamentally limited in its ability to correctly describe cuprates and many other classes of correlated materials, and that one must invoke “beyond DFT” schemes, where electron correlation effects are built in explicitly. Beyond DFT approaches involve quantum Monte Carlo methods17, and effective low-energy Hubbard Hamiltonians, which can be tackled using dynamical mean-field theory18,19, cluster dynamical mean-field theory20, and various intermediate coupling theories, see ref. 21 for a review. Such calculations, however, are computationally too intensive to be of practical use for handling the large number of degrees of freedom required for a realistic treatment of electronic states in the presence of multiple orbitals and large unit cells. An alternative scheme for describing both LCO/LSCO is DFT+U22,23, where DFT is complemented with a model Hamiltonian by adding an empirical Hubbard [U] term24,25, see Supplementary Note 1.

Here, we show that the strongly constrained-and-appropriately normed (SCAN) density functional26 presents a viable model for LCO, as well as LSCO, reproducing not only the insulating character of the parent LCO compound but also the metallic character of the Sr-doped LSCO. The SCAN functional thus enables improved structural, electronic, and magnetic property predictions in a parameter-free manner with a computational cost, which is comparable to that of GGA functionals.

Results

Electronic structure

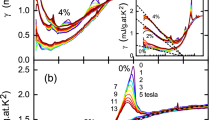

We considered electronic properties of three different structural variants of LCO/LSCO. In all these phases, the LSDA and PBE functionals fail to produce an insulating band gap in the pristine compound, Fig. 1a, consistent with previous studies. In sharp contrast, the SCAN functional correctly predicts a leading-edge band gap of ≈1 eV, in excellent agreement with the corresponding experimental value of 1.0 eV27, see Table 1. Differences between electronic structures based on SCAN and LSDA/PBE are clearly visible in the density of states (DOS) shown in Fig. 1a, where only the SCAN functional is seen to open an insulating band gap. Full electronic, crystal and magnetic structure data from all functionals is given in Supplementary Note 2.

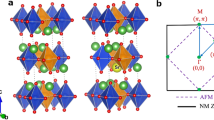

Comparison of the crystal, magnetic and electronic structures of pristine La2CuO4 (LCO) and doped La1.75Sr0.25CuO4 (LSCO). a Density of states (DOS) calculated using the LSDA48, PBE49, and SCAN26 functionals for the respective relaxed structures, illustrating the incorrect metallic prediction of LSDA and PBE(GGA). SCAN-based relaxed crystal structures of (b) pristine and (c) doped low-temperature tetragonal phases of LSCO where Cu, O, La, and Sr positions are illustrated with blue, red, green, and yellow spheres, respectively. The related AFM structure is highlighted by coloring the octahedra orange(pink) for spin up(down). c–e Effect of 25% Sr doping on the SCAN-based electronic structure, for (d) pristine LCO and (f) 25% Sr-doped LSCO. Orbital characters are shown in band structures (d, f) and DOS (e) of structures (b) and (c) for oxygen px + py (blue, filled circles) and copper \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\), pointing along the O–Cu–O bond, (red, empty circles), with marker size indicating strength of the projection

We emphasize that, unlike hybrid functionals, SCAN captures the metallic transition with doping. We illustrate this point by using a relatively simple “δ-doping” scheme (see Methods Section for details), which has been reported recently for doping LSCO via molecular beam epitaxy techniques28. As seen from the DOS plot in Fig. 1e, SCAN correctly produces the metallic character of the doped compound. To our knowledge, the ability of SCAN to simultaneously predict the correct electronic ground state for both the pristine (LCO) and the doped (LSCO) system is unique among the various density functionals. Notably, this is achieved without any empirically determined parameters in the functional form and at a modest computational cost. These results suggest that the SCAN functional should have good transferability to other classes of correlated materials.

Insight into how SCAN obtains an improved description of the insulating phase can be obtained through a connection revealed recently in ref. 29 between the fundamental band gap in a periodic N electron system and the corresponding band gap in the generalized Kohn–Sham orbitals. The connection is that, for a given density functional, the generalized Kohn–Sham gap, \(\epsilon _{{\mathrm{gap}}}^{{\mathrm{GKS}}}\), is equal to the fundamental gap defined as:

where E(N) is the total energy of the solid with N electrons. Therefore, as the SCAN functional improves energies and structures26,30,31, it must also improve orbital band gaps compared to LSDA and GGA within the generalized Kohn–Sham framework29,32.

Crystal structure

Macroscopic probes indicate that the structure of LCO contains a variety of phases, which can be characterized in terms of different CuO6 octahedral tilt modes. At high temperatures, LCO adopts tetragonal symmetry (HTT phase), where all CuO6 octahedra are axially aligned. At low temperatures, a transition to an orthorhombic phase (LTO) occurs in which the CuO6 octahedra are tilted along the (010) direction in alternate layers, bisecting the planar O–Cu–O angle. A low-temperature tetragonal (LTT) phase can also be stabilized under special conditions, e.g., by Ba doping or substitution of La with Nd, which involves octahedral tilts of the Cu–O–Cu bonds along the (110) zone diagonal. The top views of the HTT, LTO and LTT phases in Fig. 2a illustrate the corresponding in-plane distortions; a 3D representation of the LTT phase is given in Fig. 1b, c. It should be noted that local experimental probes reveal a more complicated story. Neutron powder diffraction finds a superposition of local tilting environments, wherein local domains of LTT tilts coexist in all three phases33. Moreover, there is evidence for an intimate connection between LTT tilts and the magnetic stripe phase34, suggesting that local fluctuating LTT tilts are ubiquitous throughout the LCO structure.

Structural diagrams of the three La2CuO4 phases with their electronic structures using the SCAN functional. Atomic positions illustrated are Cu (blue), La (green) and O (red). a Energy of the observed tilt modes relative to the low-temperature orthorhombic (LTO) ground state mode using relaxed crystal structures. The (010) and (110) (Cu-O-Cu bond direction) tilt modes are highlighted in the LTO and low-temperature tetragonal (LTT) phases, respectively. b The Brillouin zone path followed for all band structure plots. Both antiferromagnetic (AFM) and paramagnetic (PM) cells are highlighted. c–e Band structures and density of states for (c) high temperature tetragonal (HTT), (d) LTO and (e) LTT phases. Projected orbital characters are shown for bands of special interest: oxygen px and py and copper \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\), pointing along the O-Cu-O bond, where orbital characters are given by filled blue and empty red markers, respectively. Marker size is proportional to the strength of projection. Partial densities of states are highlighted for the various orbitals using the same color code as that used in the band structure plots, which include also the total densities of states (solid black lines)

Figure 2a shows the SCAN-predicted relative total energies for various structures, with detailed results presented in Table 1. Our results are in good agreement with the local-tilting mode picture, with the LTO phase being the most stable. The HTT phase is found to be the least stable, with

where the observed HTT-LTO transition temperature is TLTO ≈ 528 K. The LTO phase is found to have the lowest energy although the LTO-LTT difference is within the errors of the calculations. Small energy difference between the LTO and LTT phases indicates that strong mixing of these two phases should be expected, consistent with the experimental observation of local tilting domains33. Note that we would expect the experimentally observed tilts to be smaller than the corresponding computed values, as is seen to be the case in Table 1, because the experimental tilts involve an average over multiple modes. We have also carried out computations on the 25% Sr-doped LSCO. The LTT phase was found to be the ground state for the doped system, with a small LTT-LTO energy difference, consistent with the experimental observation that the LTT phase is only observed at finite doping34.

Magnetic structure of LCO

The preceding analysis gives confidence in our description of the ground state and sets the stage for addressing the more subtle nature of the magnetic structure of LCO. Here, we find that magnetic moments are localized mainly on the copper ions forming a (π, π) AFM order within the Cu–O plane. The coloring on octahedra in Fig. 1b, c illustrate the magnetic order, with purple and orange colors denoting positive and negative moments, respectively. In particular, we reproduce the experimentally measured magnetic moment of 0.48 ± 0.15 μB7,8 on copper atoms with quantitative accuracy (Table 1).

An important question in the physics of cuprates is how their physical properties are linked to their electronic structure. In fact, once an adequate description of the electronic environment of the parent compound is obtained, the emergent orders of the doped system could in principle be disentangled. There is general consensus that the gap in the cuprates is of charge–transfer rather than Mott–Hubbard35 type. It has been shown that there is a correlation between Tc and the shape of the Fermi surface36, while there is an anticorrelation between a charge–transfer type gap and Tc37. Characterization of the nature of the gap is thus of key importance in understanding the superconducting state.

In this connection, Fig. 2c–e shows that a gap opens in LCO around the EF due to the (π, π) AFM order along the nodal direction (Γ − M, Brillouin zone path illustrated in Fig. 2b) in the Cu \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\)-O px/py antibonding band. A similar splitting is also present around −7 eV in the bonding band at the M symmetry point. Irrespective of the LCO phase, character of the conduction band and the band around −7 eV is dominated by the Cu \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) orbital. In contrast, the valence band is not dominated by either Cu \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) or O px/py. In fact, the valence band contains significant contributions from Cu \(d_{z^2}\) and apical oxygen pz orbitals. These results show that the current tight-binding parameterizations of cuprates are fundamentally limited in their modeling of the underlying orbital characters. The important role of \(d_{z^2}\)-orbitals is consistent with earlier experimental observations38,39,40 and with a two-band model of Tc41. The preceding analysis also implies that the classification of the cuprates as being of charge–transfer type42, as has been assumed widely in the literature, applies when only the \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) orbital is taken into account. The cuprates are closer to being Mott-type if all d orbitals are considered as there is considerable \(d_{z^2}\) character overlapping the valence band.

Discussion

Results of Table 1 show that SCAN generally provides an improvement over LSDA and GGA(PBE) predictions of structural, electronic, energetic, and magnetic properties of LCO and LSCO. We comment on the reasons for the efficacy of the SCAN functional as follows. Compared to LSDA and GGA in which only the electron density and its gradient are considered, SCAN belongs to the class of so-called meta-GGA functionals, where the Kohn–Sham kinetic energy density is also taken into account, in addition to the electron density and its gradient. SCAN is unique in that it satisfies all known (seventeen) exact constraints applicable to a meta-GGA. In contrast, the PBE-GGA, for example, only satisfies eleven of the seventeen exact constraints. By correctly building the kinetic energy density into a dimensionless orbital-overlap indicator, SCAN distinguishes between density regions characterizing covalent and metallic bonds, and treats them properly through appropriate GGA constructions26,32, allowing SCAN to address diverse types of bondings in materials. Notably, it has been shown that a reduction of the self-interaction error in the underlying density functional is important for localizing d electrons, stabilizing the magnetic moment of Cu, and opening the band gap in LCO22,23,43,44. This implies that SCAN mitigates self-interaction error in comparison to PBE-GGA as SCAN better stabilizes the Cu magnetic moment and the band gap in LCO.

Our investigation of LCO/LSCO as an exemplar cuprate system demonstrates how the doping-dependent electronic structures of high-Tc cuprate superconductors can be modeled accurately on a first-principles basis. Our computations correctly predict the key experimentally observed features of the electronic structure and magnetism of LCO/LSCO without invoking any free parameters. AFM structures of LCO are found to be energetically quite close for various structural distortions. Our study thus opens a new pathway toward first-principles treatment of electronic structures and wide-ranging properties of correlated materials more generally.

Methods

All calculations were performed using the pseudopotential projector-augmented wave method45 implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)46,47 with an energy cutoff of 550 eV for the plane-wave basis set. Exchange-correlation effects were treated using the local density approximation48, generalized gradient approximation (GGA)49, and in the SCAN meta-GGA scheme26. In all cases an 8 × 8 × 4 Γ-centered k-point mesh was used to sample the Brillouin zone. All structures were relaxed using a conjugate gradient algorithm with an atomic force tolerance of 0.008 eV/Å and a total energy tolerance of 10−5 eV.

Rather than randomly substituting lanthanum by strontium, we substitute one La by Sr in the \(\sqrt 2 \times \sqrt 2\) AFM unit cell28, see Fig. 1a. Since all lanthanum substitution positions are equivalent by crystal symmetry in the AFM unit cell, our substitution scheme is equivalent to replacing single planes of La2O2 with LaSrO2 planes. This gives an overall effective average doping of 25%, where one Cu-O layer is doped at 50%, and the other left pristine. The overall effect of doping away from the cuprate planes is not expected to be sensitive to the detailed arrangement of dopants50, although further work using methods for treating disordered alloys51,52,53 will be interesting. Full structure definitions for all experimental and relaxed structures are provided in CIF file format in Supplementary Data file structures.txt.

Comment on calculated lattice volumes

It is interesting that the experimentally measured lattice volume in HTT LCO, measured at 528 K54, is in better accord with PBE(GGA) results, while SCAN yields an underestimate, see Table 1. This may reflect effects of thermal expansion canceling fortuitously against the overestimation of lattice volumes generally found in PBE calculations. A proper comparison between theory and experiment at high temperature should include effects of temperature and zero-point vibrations.

Calculated magnetic moments

The local magnetic moment on the copper sites is calculated within VASP by integrating the magnetic moment in the Projector augmented-wave (PAW)45 sphere of radius 2.20 Å, as set by the pseudopotential.

Ferrimagnetic structure in δ-doped LSCO

In the 25% doped LTT structure, bands of Cu \({\mathrm{d}}_{x^2 - y^2}\) character (Fig. 1c, red circles) exhibit ferromagnetic splittings absent in the pristine case. The ferromagnetic splitting is a result of the introduction of the Sr impurity, which breaks the magnetic equivalence between Cu–O planes. Moreover, this generates an imbalance in the magnetic moments between the planes giving a net magnetic moment of 0.089 μB unit cell−1. Within each Cu–O plane there are uncompensated ferrimagnetic copper magnetic moments of 0.593 μB and 0.263 μB, along with small moments on the in-plane oxygen atoms of 0.024 μB.

Data availability

Input and output files related to all calculations reported in this work have been made available through the NOMAD Repository (http://nomad-repository.eu/) and can be accessed using the digital object identifier (10.17172/NOMAD/2018.01.03-1).

References

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, 864–871 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, 1133–1139 (1965).

Yu, J., Freeman, A. J. & Xu, J.-H. Electronically driven instabilities and superconductivity in layerd La2−xBaxCuO4 perovskites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 1035–1037 (1987).

Mattheiss, L. F. Electronic band properties and superconductivity in La2−yXyCuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 1028–1030 (1987).

Pickett, W. E. Electronic structure of the high-temperature oxide superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 61, 433–512 (1989).

Ambrosch-Draxl, C. & Schwarz, K. Local-spin-density calculations of antiferromagnetic YBa2Cu3O6 and La2CuO4. Solid State Commun. 77, 45–48 (1991).

Vaknin, D. et al. Antiferromagnetism in La2CuO4−y. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 2802–2805 (1987).

Freltoft, T., Shirane, G., Mitsuda, S., Remkeika, J. P. & Cooper, A. S. Magnetic form factor of Cu in La2CuO4. Phys. Rev. B 37, 137–142 (1988).

Giustino, F., Cohen, M. L. & Louie, S. G. Small phonon contribution to the photoemission kink in the copper oxide superconductors. Nature 452, 975–978 (2008).

Singh, D. J. & Pickett, W. E. Gradient-corrected density-functional studies of CaCuO2. Phys. Rev. B 44, 7715–7717 (1991).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A. 38, 3098–3100 (1988).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Becke, A. D. A new mixing of HartreeFock and local density-functional theories. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 1372 (1993).

Stephens, P. J., Devlin, F. J., Chabalowski, C. F. & Frisch, M. J. Ab initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 11623–11627 (1994).

Perry, J. K., Tahir-Kheli, J. & Goddard, W. A. Antiferromagnetic band structure of La2CuO4: Becke-3-Lee-Yang-Parr calculations. Phys. Rev. B 63, 144510 (2001).

Perry, J. K., Tahir-Kheli, J. & Goddard, W. A. III Ab initio evidence for the formation of impurity holes in doped La2−xSrxCuO4. Phys. Rev. B 65, 144501 (2002).

Wagner, L. K. & Abbamonte, P. Effect of electron correlation on the electronic structure and spin-lattice coupling of high-T c cuprates: Quantum Monte Carlo calculations. Phys. Rev. B 90, 125129 (2014).

Kotliar, G. et al. Electronic structure calculations with dynamical mean-field theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 865–951 (2006).

Held, K. et al. Realistic investigations of correlated electron systems with LDA + DMFT. Phys. Status Solidi (B) Basic Res. 243, 2599–2631 (2006).

Park, H., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Cluster dynamical mean field theory of the mott transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 186403 (2008).

Das, T., Markiewicz, R. S. & Bansil, A. Intermediate coupling model of the cuprates. Adv. Phys. 63, 151–266 (2014).

Czyzyk, M. T. & Sawatzky, G. A. Local-density functional and on-site correlations: The electronic structure of La2CuO4 and LaCuO3. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14211–14228 (1994).

Pesant, S. & Côté, M. DFT + U study of magnetic order in doped La2CuO4 crystals. Phys. Rev. B 84, 085104 (2011).

Liechtenstein, A. I., Anisimov, V. I. & Zaanen, J. Density-functional theory and strong interactions: Orbital ordering in Mott-Hubbard insulators. Phys. Rev. B 52, 5467–5471 (1995).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA + U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Sun, J., Ruzsinszky, A. & Perdew, J. P. Strongly constrained and appropriately normed semilocal density functional. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 036402 (2015).

Uchida, S. et al. Optical spectra of La(2−x)Sr(x)CuO4: effect of carrier doping on the electronic structure of the CuO2 plane. Phys. Rev. B 43, 7942–7954 (1991).

Suter, A. et al. Superconductivity drives magnetism in delta-doped La2CuO4. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2017arXiv170607599S (2017).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Understanding band gaps of solids in generalized Kohn-Sham theory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 1–14 (2017).

Sun, J. et al. Accurate first-principles structures and energies of diversely bonded systems from an efficient density functional. Nat. Chem. 8, 831–836 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Sun, J., Perdew, J. P. & Wu, X. Comparative first-principles studies of prototypical ferroelectric materials by LDA, GGA, and SCAN meta-GGA. Phys. Rev. B 96, 035143 (2017).

Yang, Z. H., Peng, H., Sun, J. & Perdew, J. P. More realistic band gaps from meta-generalized gradient approximations: Only in a generalized Kohn-Sham scheme. Phys. Rev. B 93, 205205 (2016).

Billinge, S. J. & Kweis, G. H. Probing the short-range order and dynamics of phase transitions using neutron powder diffraction. J. Phys. Chem. Solids Solids 57, 1457–1464 (1996).

Tranquada, J. M., Sternlieb, B. J., Axe, J. D., Nakamura, Y. & Uchida, S. Evidence for stripe correlations of spins and holes in copper oxide superconductors. Nature 375, 561–563 (1995).

Damascelli, A., Hussain, Z. & Shen, Z.-X. Angle-resolved photoemission studies of the cuprate superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 473–541 (2003).

Pavarini, E., Dasgupta, I., Saha-Dasgupta, T., Jepsen, O. & Andersen, O. K. Band-structure trend in hole-doped cuprates and correlation with Tcmax. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 047003 (2001).

Ruan, W. et al. Relationship between the parent charge transfer gap and maximum transition temperature in cuprates. Sci. Bull. 61, 1826–1832 (2016).

Pines, D. et al. Imaging doped holes in a cuprate. Science 332, 698–703 (2011).

Peets, D. C. et al. X-ray absorption spectra reveal the inapplicability of the single-band Hubbard model to overdoped cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 087402 (2009).

Sakurai, Y. et al. Imaging doped holes in a cuprate superconductor with high-resolution compton scattering. Science 332, 698–702 (2011).

Sakakibara, H., Usui, H., Kuroki, K., Arita, R. & Aoki, H. Two-orbital model explains the higher transition temperature of the single-layer Hg-cuprate superconductor compared to that of the La-cuprate superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 057003 (2010).

Zaanen, J., Sawatzky, G. A. & Allen, J. W. Band gaps and electronic structure of transition-metal compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 418–421 (1985).

Svane, A. Electronic structure of La2CuO4 in the self-interaction-corrected density functional formalism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 1900–1903 (1992).

Cococcioni, M. & de Gironcoli, S. A linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction parameters in the LDA+U method. Phys. Rev. B 71, 035105 (2004).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 48, 13115–13118 (1993).

Perdew, J. P. & Zunger, A. Self-interaction correction to density-functional approximations for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5048–5079 (1981).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Lin, H., Sahrakorpi, S., Markiewicz, R. S. & Bansil, A. Raising Bi–O bands above the fermi energy level of hole-doped Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ and other cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 097001 (2006).

Bansil, A. Coherent-potential and average t-matrix approximations for disordered muffin-tin alloys. I. formalism. Phys. Rev. B 20, 4025 (1979).

Bansil, A. Coherent-potential and average t-matrix approximations for disordered muffin-tin alloys. II. Application to realistic systems. Phys. Rev. B 20, 4035 (1979).

Bansil, A., Rao, R. S., Mijnarends, P. E. & Schwartz, L. Electron momentum densities in disordered muffin-tin alloys. Phys. Rev. B 23, 3608 (1981).

Onoda, M., Shamoto, S.-i., Sato, M. & Hosoya, S. Novel Superconductivity, vol. 1, 919–920 (Plenum Press, New York, 1987).

Jorgensen, J. D. et al. Superconducting phase of La2CuO4 + δ: a superconducting composition resulting from phase separation. Phys. Rev. B 38, 11337–11345 (1988).

Cox, D. E. et al. Structural studies of La2−xBaxCuO4 between 11 and 293 K. MRS Proc. 156, 141–151 (1989).

Acknowledgements

The work at Tulane University was supported by the start-up funding from Tulane University and by the DOE Energy Frontier Research Centers (development and applications of density functional theory): Center for the Computational Design of Functional Layered Materials (DE-SC0012575). The work at Northeastern University was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences grant number DE-FG02-07ER46352 (core research) and benefited from Northeastern University’s Advanced Scientific Computation Center, the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center supercomputing center (DOE grant number DE-AC02-05CH11231), and support (testing the efficacy of new functionals in diversely bonded materials) from the DOE Energy Frontier Research Centers: Center for the Computational Design of Functional Layered Materials (DE-SC0012575).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W.F., Y.Z., C.L. and I.G.B. performed computations and analyzed the data. B.B., R.S.M., A.B. and J.S. led the investigations, designed the computational approaches, provided computational infrastructure and analyzed the results. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Furness, J.W., Zhang, Y., Lane, C. et al. An accurate first-principles treatment of doping-dependent electronic structure of high-temperature cuprate superconductors. Commun Phys 1, 11 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-018-0009-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-018-0009-4

This article is cited by

-

Correlation versus hybridization gap in CaMn\(_{2}\)Bi\(_{2}\)

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Origin of superconductivity in hole doped SrBiO3 bismuth oxide perovskite from parameter-free first-principles simulations

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

Emergence of competing electronic states from non-integer nuclear charges

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Pronounced interplay between intrinsic phase-coexistence and octahedral tilt magnitude in hole-doped lanthanum cuprates

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Role of Sr doping and external strain on relieving bottleneck of oxygen diffusion in La2−xSrxCuO4−δ

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.