Abstract

Topological insulators insulate in the bulk but exhibit robust conducting edge states protected by the topology of the bulk material. Here, we design a colloidal topological insulator and demonstrate experimentally the occurrence of edge states in a classical particle system. Magnetic colloidal particles travel along the edge of two distinct magnetic lattices. We drive the colloids with a uniform external magnetic field that performs a topologically non-trivial modulation loop. The loop induces closed orbits in the bulk of the magnetic lattices. At the edge, where both lattices merge, the colloids perform skipping orbits trajectories and hence edge-transport. We also observe paramagnetic and diamagnetic colloids moving in opposite directions along the edge between two inverted patterns; the analogue of a quantum spin Hall effect in topological insulators. We present a robust and versatile way of transporting colloidal particles, enabling new pathways towards lab on a chip applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topologically protected quantum edge states arise from the non trivial topology (non-vanishing Chern number) of the bulk band structure1. If the Fermi energy is located in the gap of the bulk band structure, like in an ordinary insulator, edge currents might propagate along the edges of the bulk material. The edge currents are protected as long as perturbations to the system do not cause a band gap closure. The topological mechanism at work is not limited to quantum systems but has been shown to work equally well for classical photonic2,3, phononic4,5, solitonic6, gyroscopic7, coupled pendulums8, and stochastic9 waves. It is also known that the topological properties survive the particle limit when the particle size is small compared to the width of the edge. In the semi-classical picture of the quantum Hall effect, the magnetic field enforces the electrons to perform closed cyclotron orbits in the bulk of the material. Near the edge, the electrons can only perform skipping orbits, i.e., open trajectories that allow electronic transport along the edge10. Considerable effort to simulate such semi-classical trajectories has been undertaken10,11,12,13. Their experimental observation, however, is quite difficult. So far, skipping orbits were only observed in two dimensional electron gas driven by microwaves14 and with neutral atomic fermions in synthetic Hall ribbons15.

We present here the experimental observation in a colloidal system of skipping orbits and hence edge states. These edge states allow for a robust transport of colloids along the edges and also the corners of the underlying magnetic lattice.

Results

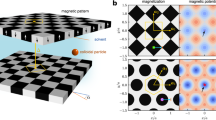

We use a thin cobalt-based magnetic film lithographically patterned via ion bombardment16,17,18. The pattern consists of a patch of hexagonally arranged circular domains (mesoscopic pattern lattice constant a ≈ 7 µm) surrounded by a stripe pattern, see Fig. 1a. Both magnetic regions consist of alternating domains magnetized in the ±z-direction normal to the film. Paramagnetic colloidal particles of diameter 2.8 µm are immersed in water (or aqueous ferrofluid) and move at a fixed elevation above the pattern. Hence, the particles move in a two-dimensional plane that we refer to as action space, \({\cal A}\). A uniform time-dependent external magnetic field Hext(t) of constant magnitude (Hext = 4kAm−1) is superimposed to the non-uniform and time-independent magnetic field of the pattern Hp. We vary Hext(t) on the surface of a sphere that we call the control space \({\cal C}\) (Fig. 1b).

Colloidal topological insulator. a Paramagnetic colloids are confined at a constant distance above a magnetically structured film of thickness 3.5 nm with regions of positive (white) and negative (black) magnetization perpendicular to the film. The film is a hexagonal lattice embedded into a stripe pattern. b Control space \({\cal C}\) for a hexagonal lattice: twelve bifurcation points (empty circles) connected by segments (solid lines). Winding around a pair of equal color segments moves the colloids one unit cell along one of the hexagonal directions. The modulation loop used here is indicated by dashed lines and also in the legend. The loop starts at the red square and winds anticlockwise twice around each pair of equal color segments

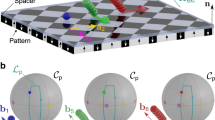

In Refs. 18–20. we demonstrate how bulk transport of colloids above different magnetic lattices can be topologically protected. For each lattice symmetry there exist special modulation loops of Hext in \({\cal C}\) that induce transport of colloids in \({\cal A}\). These loops share a common feature, they wind around special objects in \({\cal C}\)18,19,20. For a hexagonal, six-fold symmetric lattice, the control space of paramagnetic colloids is characterized by twelve points connected by six pairs of segments (Fig. 1b). A modulation loop encircling one pair of segments in \({\cal C}\) transports the colloids in \({\cal A}\) one unit cell along one of the six possible directions of the hexagonal lattice \(\pm {\mathbf a}_1^{\mathrm{h}},{\mathbf a}_2^{\mathrm{h}}, \pm ({\mathbf a}_1^{\mathrm{h}} - {\mathbf a}_2^{{\mathrm{h}}})\), with \({\mathrm{a}}_1^{\mathrm{h}}\), and \({\mathrm{a}}_2^{\mathrm{h}}\) the lattice vectors. For example, encircling the red segments in Fig. 1b transports the paramagnetic particles into the \(({\mathbf a}_1^{\mathrm{h}} - {\mathbf a}_2^{\mathrm{h}})\)-direction. If we now rotate the modulation loop such that it encircles the yellow segments, the transport occurs along \({\mathbf a}_1^{\mathrm{h}}\), i.e., the transport direction rotates π/3 with respect to the previous \(({\mathbf a}_1^{\mathrm{h}} - {\mathbf a}_2^{\mathrm{h}})\)-direction. Using these results we construct a hexagonal cyclotron orbit of hexagonal side length nah, n = 1,2,3... of a paramagnetic particle above the bulk of a hexagonal lattice. The corresponding cyclotron modulation loop in \({\cal C}\) consists of six connected parts. Each of the six parts of the loop winds n times around a different pair of segments of \({\cal C}\), and therefore transports a particle n unit cells along one of the hexagonal directions in \({\cal A}\). In Fig. 1b we show a n = 2 cyclotron modulation loop in \({\cal C}\). The corresponding colloidal trajectory in \({\cal A}\) is depicted in Fig. 2a, b. Colloidal particles above the bulk of the hexagonal pattern perform closed hexagonal cyclotron orbits of the desired side length. The cyclotron modulation loop does not wind around the special objects in \({\cal C}\) for a stripe pattern (located on the equator of \({\cal C}\)18). Hence, the colloids above the stripes are not transported. For the current modulation loops, the edge between the hexagonal and the stripe pattern is an edge between topologically non-trivial and trivial patterns, and allows for the existence of edge states, as it is the case in quantum topological insulators. Edge states are possible for those particles close to the edge between both patterns. The paramagnetic particles perform skipping orbits, see Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Movie 1. That is, the particles do not follow all six directions of the closed cyclotron orbit but skip one of the hexagonal directions. The skipping direction is different for different orientations of the edge. A successive series of these skipping orbits results in an open trajectory along the edge direction. The skipping orbits allow for robust transport in armchair edges, i.e., edges oriented along one of the six directions of the hexagonal lattice, and also around the corners where two edges join.

Skipping and bulk orbits. a Microscopy images of paramagnetic colloidal particles at the end of a transport process. Scale bar 15µm. Three trajectories are shown and indicated: a bulk orbit on top of the hexagonal pattern, a skipping orbit at the edge, and the trivial motion of a particle above the stripe pattern. The color of the trajectories matches that of the modulation loop (Fig. 1b). The edge between the hexagonal and the stripe patterns is indicated by a dashed yellow line. The colloidal motion can be seen in the Supplementary Movie 1. b Colloidal trajectories superimposed on the actual magnetic pattern. c Bulk (top) and skipping (bottom) orbits superimposed on action space, \({\cal A}\). The white (black) areas are allowed (forbidden) regions for the colloids. The grey area is the indifferent region on top of the stripe pattern. In the skipping orbits the colloids skip the green section of the bulk-trajectory. Three gates connecting adjacent allowed regions are highlighted with orange circles in the top panel

The skipping of single directions can be explained by taking a closer look at the bulk transport mechanism, explained in detail in Refs. 18–20. Here, we just summarize the main concepts. For a fixed external field there are stationary points of the magnetic potential in each unit cell of the magnetic lattice. The colloids are transported by following the minima of the magnetic potential. Action space can be split into allowed, forbidden, and indifferent regions. In the allowed regions the stationary points are minima, whereas in the forbidden regions the only possible stationary points are saddle points. No extrema of the total magnetic potential exist in the indifferent regions, which are present only in stripe patterns. Therefore, the colloids can occupy only allowed and indifferent regions. We show in Fig. 2c the split of \({\cal A}\) into the different types of regions for the current pattern. Two adjacent allowed regions touch each other at special points in \({\cal A}\) that we refer to as the gates. To achieve transport between adjacent unit cells, a colloid has to pass through two gates. In the bulk of the hexagonal lattice transport is possible along all six crystallographic directions19. However, close to the edge this is no longer true. The necessary gates to transport the particle into the edge or parallel to it are no longer available. In consequence those particles close to the edge have to perform skipping orbits.

Transport above an infinite lattice remains unchanged if the magnetization of both the pattern and the colloidal particles is inverted. Thus, diamagnetic particles (magnetic holes) on a pattern respond to the external field in the same way as paramagnetic particles on an inverted pattern. In Fig. 3 and Supplementary Movie 2 we show the chiral response of paramagnetic and diamagnetic particles at the edge between two hexagonal patterns with inverted magnetization. The susceptibility of the ferrofluid-based solvent is set to a value in between the effective particle susceptibilities. We use the same cyclotron modulation loop as before. The loop induces anticlockwise cyclotron orbits of paramagnets on the bulk of one lattice and of diamagnets on the bulk of the inverted lattice. Near the edge, both types of colloids perform skipping orbits above the pattern that is non-trivial for them. Since the edge between both patterns is located in opposite directions from the center of the corresponding orbits, the skipping directions are antiparallel. Hence, this results in skipping orbits along the edge where both types of particles move on opposite sides of the edge in opposite directions. This represents the colloidal analogue of the quantum spin Hall effect21, in which electrons of opposite spins move in different directions along the same edge.

Colloidal spin Hall effect. Trajectories followed by a paramagnetic (red) and a diamagnetic (blue) particle along the edge (yellow lines) of two hexagonal magnetic patterns with opposite magnetization. The scale bar is 7 µm. The particles are driven by the modulation loop shown in Fig. 1b. The magnetic moment m of the paramagnets (diamagnets) is parallel (antiparallel) to the total magnetic field H. A video of the colloidal motion is provided in the Supplementary Movie 2

Discussion

A nontrivial topology of the shape of colloidal particles can be used to control the formation of topological defects in a nematic host22,23. Here we have used topology in a dynamic way to control the motion of colloidal particles. We experimentally demonstrated how to realize a colloidal topological insulator. Like in the semi-classical picture of the quantum Hall effect, particles above the bulk of the material move following closed orbits, and particles close to the edge perform skipping orbits giving rise to robust edge states. The fine details of the pattern are irrelevant to determine the bulk transport properties18. At the edges, however, transport does depend on the details of the pattern. For example the exact positions of the stripes with respect to the circular domains and the orientation of the edges influence the edge states. Similar effects are also observed in graphene, where only certain edges support edge states. The versatility of our robust colloidal transport opens the possibility to transport multiple particles along multiple different edges into different directions using just a unique external modulation.

Our skipping orbits are an example of a purely geometric trajectory. As long as the modulation period T is slow enough, i.e., T ≳ 10s, and the external magnetic field is sufficiently strong, Hext ≳ 0.5 kAm−1, the transport of the colloids does neither depend on the period, nor does it depend on the absolute value of the external field. Under those conditions only a small fraction of the colloidal particles, which adhere to the surface of the magnetic film, is not transported. The displacement over one period of the mobile particles, however, does only depend on the initial position of the particles with respect to the edge of the hexagonal pattern: particles in the bulk show no displacement over one period, while particles close to the edge are displaced parallel to the edge. The strongest limitation is therefore the period of the modulation, which is solely imposed by the magnetization of the pattern. Modulation periods orders of magnitude faster can be achieved by using e.g., garnet films19,24.

Here we have worked at a low particle density: less than one particle per unit cell. New phenomenology will arise at high densities due to excluded volume effects. We expect for example quantized particle edge currents, as have been observed in the hexagonal bulk25.

Colloids can be used to mimic aspects of molecules26 and atoms27. Our colloidal topological insulator goes a step further and mimics the behaviour of electrons in a colloidal system.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Rechtsman, M. C. et al. Photonic Floquet topological insulators. Nature 496, 196–200 (2013).

Perczel, J. et al. Topological quantum optics in two-dimensional atomic arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 023603 (2017).

Kane, C. L. & Lubensky, T. C. Topological boundary modes in isostatic lattices. Nat. Phys. 10, 39–45 (2014).

Xiao, M. et al. Geometric phase and band inversion in periodic acoustic systems. Nat. Phys. 11, 240–244 (2015).

Paulose, J., Chen, B. G. & Vitelli, V. Topological modes bound to dislocations in mechanical metamaterials. Nat. Phys. 11, 153–156 (2015).

Nash, L. M. et al. Topological mechanics of gyroscopic metamaterials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 14495–14500 (2015).

Huber, S. D. Topological mechanics. Nat. Phys. 12, 621–623 (2016).

Murugan, A. & Vaikuntanathan, S. Topologically protected modes in non-equilibrium stochastic systems. Nat. Commun. 8, 13881 (2017).

Beenakker, C. W. J., van Houten, H. & van Wees, B. J. Skipping orbits, traversing trajectories, and quantum ballistic transport in microstructures. Superlattices Microstruct. 5, 127–132 (1989).

Davies, N. et al. Skipping and snake orbits of electrons: singularities and catastrophes. Phys. Rev. B 85, 155433 (2012).

Shi, L., Zhang, S. & Chang, K. Anomalous electron trajectory in topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 87, 161115 (2013).

Montambaux, G. Semiclassical quantization of skipping orbits. Eur. Phys. J. B 79, 215–224 (2011).

Zhirov, O. V., Chepelianskii, A. D. & Shepelyansky, D. L. Towards a synchronization theory of microwave-induced zeroresistance states. Phys. Rev. B 88, 035410 (2013).

Mancini, M. et al. Observation of chiral edge states with neutral fermions in synthetic Hall ribbons. Science 349, 1510–1513 (2015).

Chappert, C. et al. Planar patterned magnetic media obtained by ion irradiation. Science 280, 1919–1922 (1998).

Kuświk, P. et al. Colloidal domain lithography for regularly arranged artificial magnetic out-of-plane monodomains in Au/Co/Au layers. Nanotechnology 22, 095302 (2011).

Loehr, J. et al. Lattice symmetries and the topologically protected transport of colloidal particles. Soft Matter 13, 5044–5075 (2017).

Loehr, J., Loenne, M., Ernst, A., de las Heras, D. & Fischer, Th. M. Topological protection of multiparticle dissipative transport. Nat. Commun. 7, 11745 (2016).

De las Heras, D., Loehr, J., Loenne, M. & Fischer, Th. M. Topologically protected colloidal transport above a square magnetic lattice. New J. Phys. 18, 105009 (2016).

Bernevig, B. A. & Zhang, S.-C. Quantum spin hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 106802 (2006).

Senyuk, B. et al. Topological colloids. Nature 493, 200–205 (2013).

Martinez, A., Hermosillo, L., Tasinkevych, M. & Smalyukh, I. I. Linked topological colloids in a nematic host. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 4546–4551 (2015).

Tierno, P., Johansen, T. H. & Fischer, Th. M. Localized and delocalized motion of colloidal particles on a magnetic bubble lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 038303 (2007).

Tierno, P. & Fischer, Th. M. Excluded volume causes integer and fractional plateaus in colloidal ratchet currents. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 048302 (2014).

Glotzer, S. C. & Solomon, M. J. Anisotropy of building blocks and their assembly into complex structures. Nat. Mat. 6, 557–562 (2007).

Poon, W. Colloids as big atoms. Science 304, 830–831 (2004).

Acknowledgements

A.T. was supported by PhD fellowship of the University of Kassel. This work was supported by the University of Bayreuth open access fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., D.d.l.H., and T.M.F. designed and performed the experiment, and wrote the manuscript with input from all the other authors. A.J., M.U., and F.S. produced the magnetic film. A.T., R.H., I.K., A.E., and D.H. performed the fabrication of the micromagnetic domain patterns within the magnetic thin film.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Loehr, J., de las Heras, D., Jarosz, A. et al. Colloidal topological insulators. Commun Phys 1, 4 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-017-0004-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-017-0004-1

This article is cited by

-

Disorder scattering in classical flat channel transport of particles between twisted magnetic square patterns

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Magnetic patterning of Co/Ni layered systems by plasma oxidation

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Thermally active nanoparticle clusters enslaved by engineered domain wall traps

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Noether’s theorem in statistical mechanics

Communications Physics (2021)

-

Ice rule fragility via topological charge transfer in artificial colloidal ice

Nature Communications (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.