Abstract

Studying the charge dynamics of perovskite materials is a crucial step to understand the outstanding performance of these materials in various fields. Herein, we utilize transient absorption in the mid-infrared region, where solely electron signatures in the conduction bands are monitored without external contributions from other dynamical species. Within the measured range of 4000 nm to 6000 nm (2500–1666 cm−1), the recombination and the trapping processes of the excited carriers could be easily monitored. Moreover, we reveal that within this spectral region the trapping process could be distinguished from recombination process, in which the iodide-based films show more tendencies to trap the excited electrons in comparison to the bromide-based derivatives. The trapping process was assigned due to the emission released in the mid-infrared region, while the traditional band-gap recombination process did not show such process. Various parameters have been tested such as film composition, excitation dependence and the probing wavelength. This study opens new frontiers for the transient mid-infrared absorption to assign the trapping process in perovskite films both qualitatively and quantitatively, along with the potential applications of perovskite films in the mid-IR region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hybrid perovskite materials have recently attracted lots of attention due to their unique photo-physical properties and their high performances in various applications such as solar cells and light emitting diodes1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. However, still controlling the amount of traps present in these materials especially upon making thin films is a challenging procedure18,19. The presence of trap states either through structural defects or other types can quench the charge carriers motilities inside the materials and thus reducing both the device’s performance and its stability8,18,20,21,22,23. Various direct and indirect methods have been applied to track and quantify trap states such as electrical or optical measurements, however, most of these still have some drawbacks8,18,19,20,21,22,24. For instance, conductivity measurements have low time resolutions and can’t distinguish between various carriers such as electrons and holes especially upon having close motilities25. Also, the most commonly used optical measurements such as time-resolved photoluminescence or transient absorption in the visible range couldn’t afford direct spectral signatures for trapping states except providing variations of multi-exponential kinetic rates between different samples according to the estimated traps present in the investigated samples1,2,7,13,15,26,27. Thus, still there is a need for a direct transient optical method to track and quantify the trapping process in perovskite materials, and correlate their presence directly to charge dynamics. For that sake, we utilized mid-infrared (mid-IR) probe to monitor the charge dynamics of four different perovskite films with different compositions. Following the charge dynamics using femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) in the mid-IR has been used previously for several systems including metal complexes28,29,30,31, organic dyes32,33,34,35,36,37, metals38, and semiconductors21,25,39,40,41,42,43.

Basically for classical semiconductors, the electron’s absorption in the conduction band with high density of states has a broad spectral signature extending from 3333 nm (3000 cm−1) to 11,111 nm (900 cm−1), in which other contributions from cationic or anionic molecular species present can be easily quantified25,28,32,33. The positive signature in the mid-IR upon photon excitation is ascribed to the presence of intra-transition of free electrons in/into the conduction band of the semiconductor used25,43,44. The transient mid-IR was used to follow trapped electrons at the mid-gap shallow states in the platinized TiO2 system, in which IR emission is evolved in the IR region as a result of electron trapping process25,43. Recent mid-IR studies have been done on perovskite materials, however in those studies the authors focused on following the NH vibrational modes, present in the organic cationic part of the perovskites20,21,26,45. In contrast, in our selected mid-IR region, we don’t have any contribution of the vibrational modes of the organic part, only transient signal of electrons in the conduction band, see Fig. S1.

Herein, we propose using fs-TA in the mid-IR region as a sensitive tool to follow the presence of traps in hybrid perovskite films. In the current study, various hybrid perovskite films have been synthesized and utilized to study the charge dynamics in the mid-IR region extending from ca. 4000–6000 nm (2500–1666 cm−1). We found that perovskite films with methyl-ammonium cation (MA) and halides of Iodide (I) derivatives tend to emit mid-IR than other films with formamidinium (FA) and bromide (Br) derivatives, depending on the working conditions and the quality of the prepared films (see steady state measurements in Figs. S2–4). This study presents deeper understandings of charge dynamics in perovskite films, and potential applications of perovskite films in the mid-IR region.

Results and discussion

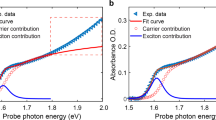

Figure 1A shows the false 2-D plot of fs-TA in the mid-IR region with a central detection window of 5000 nm (2000 cm−1) for MAPbBr3 thin film using an excitation wavelength of 530 nm. At time zero, an intense positive signal appears due to the population of electrons in the conduction band as described for previous semiconductors such as TiO228,32,43,46. The contribution of holes in the valence band is expected to be minimum due the low energy of the probed light in the mid-IR range, however, further studies are needed to certify that. This positive signal decays exponentially toward zero within few nanoseconds. However, the extracted spectra show negative features at longer time scale >1.0 ns; see Fig. 1B. The extracted kinetic trace at 4900 nm shows a multi-exponential decay for the positive signal with an average lifetime of 120 ps, followed by a small negative feature beyond 2 ns; see Fig. 1C.

(A) 2D-false color plot of fs-transient absorption in the mid-infrared regions for MAPbBr3 film using 530 nm as an excitation source. B Extracted spectra for transient spectra in mid-infrared region, the spectra are corrected for the wavelength scale. C Extracted kinetic trace at 4900 and 5120 nm with corresponding fitting, green shaded area highlights the appearance of negative signal. D Comparison between normalized kinetic traces in the infrared and visible ranges for MAPbBr3 film.

The same film (MAPbBr3) was measured by fs-TA in the visible range, and an extracted kinetic trace at 550 nm corresponding to the ground state bleach (GSA) is compared with the extracted kinetic trace at 4900 nm from the mid-IR region; see Fig. 1D and Fig. S5. The comparison shows that both normalized kinetic traces from different spectral regions are very similar, except the presence of a new feature at the extracted kinetic trace from the mid-IR range; see Fig. 1C–D. The similarity between the two kinetic traces for MAPbBr3 film confirms the validity of mid-IR signal to trace charge dynamics in perovskite films. However, the charge dynamics in the mid-IR region are not similar. For example, negative features at the red-part of the false 2D plot (at 4900 nm) in Fig. 1A, appears differently than in the blue-part (at 5120 nm). Extracting a kinetic trace at 5120 nm (1953 cm−1) shows earlier conversion of positive to negative signals at ca. 200 ps; see Fig. 1C. Also, comparing this kinetic trace with the one extracted from the GSB in the visible region, shows different behavior than kinetic trace at 4900 nm; see Fig. 1D. This highlights the dependence of such negative feature on the probed spectral window.

Upon measuring the iodide-derivative, MAPbI3 film, a detectable fs-TA mid-IR signal was also found, but with different behavior, see Fig. 2A, B. Interestingly, the transient mid-IR signal for MAPbI3 film was changing over minutes time scale (minutes); see Fig. 2C. Thus, various kinetic traces were extracted at different times and compared together at the same probed wavelength. For instance, the fresh-irradiated film (~ 0 min.), appositive signal was measured until ca. 100 ps, and then a small negative signal started to emerge. The disappearance of the positive signal became faster with the longer the exposure process associated with an increase of the negative signal at early times; see Fig. 2C. For example, after 26 min of irradiation, the positive signal converted into a negative signal within 10 ps; see Fig. 2C. Interestingly, this process is reversible, in which switching off the irradiation for almost 8 min, and re-measure the dynamics again at the same irradiated spot (@ ~ 34 min in the Fig. 2C), the dynamics slowly started to be similar to the 10 min irradiation measurements; see Fig. 2C. In all cases, after the appearance of the negative signal, it decays later on to zero due to the expected recombination process, see Fig. 2C.

(A) 2D-false color plot for fs-transient absorption in the mid-infrared regions for MAPbI3 film using 530 nm as an excitation source after 26 minutes of irradiation. B Extracted spectra for transient spectra in mid-infrared region (A), the spectra are corrected for the wavelength scale. C Extracted kinetic trace at 4900 nm at different irradiation time shown in minutes for MAPbI3 film, using 520 nm with excitation power of 500 µW. D Comparison between normalized kinetic traces in the infrared and visible ranges for MAPbI3 film.

Upon measuring the same film in the visible range, a strong GSB signal at ca. 760 nm was observed overlapping with an ESA spectra extending from 650 to 850 nm, see Fig. S7. However, no unique change in dynamics has been observed in the visible range similar to the shown data in the mid-IR range. And upon comparing the extracted normalized visible kinetic trace at 760 nm with the ones from the mid-IR, it is evident that the visible kinetic trace is similar to the one from mid-IR at 26 min only at early times; see Fig. 2D. However, still at later times, the mid-IR signal switches its sign, but not the visible kinetic trace at 760 nm. The change of charge dynamics upon irradiation in the mid-IR region has been assigned in iodide-rich perovskite materials to halide-defects assisted by the low energy needed for defects formation18,47,48,49. This comparison highlights also that this appearance of negative features in the mid-IR region is a dynamical process and also can be reversible (MAPbI3 case).

The extracted kinetic trace at 4900 nm from the MAPbI3 shows stronger and earlier negative signal than the one shown in MAPbBr3 case. Moreover, for further confirmation of the working conditions, a reference silicon wafer substrate was measured under the same procedure, and no negative features have been detected, see Fig. S8. Thus, we assign these strong negative signatures in the mid-IR for MAPbI3 film to the emissive trapping process near the VB of perovskites, confirming previous studies about tendencies of iodide-based perovskites to form more trap states than Br ones1,8,15,18.

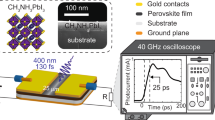

To scrutinize our interpretation about the sensitivity of mid-IR toward trapping process, we performed the same measurements on other perovskite films including FAPbBr3, FAPbI3 and mixture of their halides. For the FAPbBr3 film, the mid-IR signal shows primarily a strong negative signal close to time zero converting into a positive signal with a lifetime of ca. 60 fs, which has been assigned to the exciton thermalization/dissociation process;7 see Fig. 3A, B. Previously, in the MAPbBr3 film, exciton binding energy seems to be smaller, thus, no detection of exciton dissociation process could be seen; see Fig. 1. The charge recombination in the FAPbBr3 film (decay of the TA signal) has been fitted with multi exponential behavior, giving an average lifetime is about 10 ps, see Fig. 3B.

(A) 2D-false color plot for fs-transient absorption in the mid-infrared regions for FAPbBr3 film using 530 nm as an excitation source. B Extracted kinetic trace at 4880 nm for FAPbBr3 film. C 2D-false color plot for fs-transient absorption in the mid-infrared regions for FAPbI3 film using 530 nm as an excitation source. D Extracted kinetic trace at 4960 nm for FAPbI3 film.

For the FAPbI3 film, similar observation was estimated for the lifetime needed of exciton dissociation in FAPbI3 film; see Fig. 3C, D. However, instead of charge recombination, the measured positive signal converted again to a negative signal due to a trapping process of time component ca. 8.5 ps; see Fig. 3D. Then the trapped electrons recombine slowly with a lifetime higher than 1 ns. It is clear now that this negative signature in the mid-IR range is associated with the iodide derivative of hybrid perovskite films.

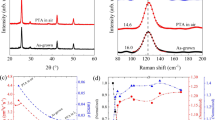

To verify the role of iodide anion for the formation of emissive trapping centers, we also synthesized other set of various perovskite films of different ratios between the iodide and Br halides (MAPbInBr3-n) to investigate the effect of doping with iodide ions on the presence of such negative signal. Figure 4A shows the kinetic traces of mid-IR signals for four films of MAPbInBr3-n, in which n varies from 0 to 3. The extracted kinetics at 4900 nm show the appearance of negative signals at different times ranging from 100 ps to 1 ns depending on the amount of iodide halide present, in which higher content of iodide shows faster appearance of negative mid-IR signal, showing that the iodide content in perovskite films controls the appearance of the negative signal (emission of mid-IR).

Dependence on chemical composition: (A) Normalized kinetic traces at 4900 nm extracted form MAPbInBr3-n films using 520 nm as excitation showing the appearance of negative signals. Dependence on mid-IR detection window: (B) Normalized Kinetic traces for MAPbI3 film under excitation of 520 nm and at different probing wavelengths showing the appearance of negative signals. Dependence on excitation wavelengths: (C) Normalized kinetic traces for MAPbI3 film under various excitation wavelengths showing the appearance of negative signals.

To study the dependence of appearance of these negative signals on the energy of the mid-IR probe, the MAPbI3 film is excited at 520 nm (300 µW), and probed at various mid-IR energy ranging from 4000 nm to 6000 nm, as shown in Fig. 4B. As expected, the appearance time of the negative signal depends on the utilized mid-IR energy, in which the switching points from positive to negative signal happen at ca. 500 ps when using 4000 nm, and at ca. 20 ps upon using 6000 nm probes.

Furthermore, by changing the excitation wavelength from 410 nm to 520 nm for another MAPbI3 film, the extracted kinetic traces at 4500 nm show a dependence of the kinetic decay with the wavelength used; see Fig. 4C. The appearance of negative signal is faster upon using 410 nm then became slower with 440 nm, and 520 nm respectively. Upon using the excitation light at 520 nm, the kinetic trace decay to zero with no signature of negative signal, despite that higher power was used, almost 20 times higher (300 µW) than at 410 nm; see Fig. 4C. This excitation energy dependence shows that the higher the electron can be promoted in the excited state, the higher chances to be trapped in emissive centers. Apparently, these emissive centers are formed during the excitation process of perovskite films.

From the above mid-IR transient measurements, the following mechanism can be drawn, see Fig. 5. Upon exciting the perovskite film, electrons in the CB should absorb the following mid-IR probe to populate various vibrational levels in the excited state, giving a positive transient absorption signal. Due to the presence of trap states within the bandgap of the perovskite film, electrons in the CB decay non-radiatively to the ground state (channel 1 in Fig. 5), in which the transient signal decays to zero as shown in FAPbBr3, Fig. 3. Interestingly, upon synthesizing perovskite films using chemical species such as MA+ or I− or both of them as in MAPbI3, negative transient signal in the mid-IR region starts to appear. And since perovskite films have no characteristic features in this mid-IR region, this negative transient signal can be only due to emission of mid-IR signal or mid-IR gain (channel 2 in Fig. 5). It has been already established in the literature that MA/iodide perovskite films show more potential to form trap states than other derivatives (FA/Br)1,15. In addition, these mid-IR gain can be controlled by the incident excitation energy, see Fig. 4C. Thus, we postulate that in MAPbI3 films, different kind of emissive trap states are additionally formed related to ion migration and formation of transient phonon modes that are not present for instance in the FAPbBr3 films1,15,50.

Interestingly, to detect these mid-IR emissive states, suitable probe energy should be utilized as shown in Fig. 4B. The probe energy data presents the influence of the energy carried by the probing photons to free/decouple the trapped electrons if sufficient energy is present. For instance, the probed pulse at 4000 nm (2500 cm−1) can liberate the trapped electron more efficient than at 6000 nm (1666 cm−1), and the appearance of mid-IR negative signal upon using 4000 nm (2500 cm−1) will not appear early, until 500 ps. In the same way, the appearance of negative signal at 6000 nm (1666 cm−1) is much faster, due to the low energy carried by the probe pulse to liberate the trapped electron in the emissive states, instead allowing for deactivation through the IR stimulated emission. These observations are consistent with a previously proposed mechanism that trapped electrons can be excited thermally if the energy difference between the trap state and the CB is small, <50 meV25. This also illustrates the incapability of transient absorption in the visible region to detect such a trapping process due to the higher energy carried by the visible probed light, that have the potential to liberate the trapped carriers into higher excited state, producing undistinguishable signal for the trapping process in the visible region, in which the excited electrons can be only deactivated via non-emissive trapping centers. According to the current range of probed energy utilized, it is expected that the high energy probe >1 eV will lead to deactivation through non-radiative centers, while <0.3 eV will stimulate mid-IR emission, see Fig. 5.

Moreover, upon using higher band-gap excitations such as 410 nm, the probability of electron trapping in these emissive states is increased despite the excitation intensity used, matching with the expected distribution for the states of trap-density present. We also show that continuous irradiation at high excitation energy for the MAPbI3 film (Fig. 2C) increases the rate of trapping (channel 2 in Fig. 5), as well as the intensity of the transient signal. This indicates toward the exciting correlation between the light irradiation and ion migration process in perovskite films51. This means that changes in the perovskite lattice by the incident light (depending on energy) can lead to the formation of these emissive trapping states at different energy levels above the VB.

Conclusion

We show herein for the first time that transient absorption in the mid-IR region is a suitable spectroscopic tool to explore trapping process in addition to follow the behavior of free electrons in the conduction band without other contributions of other species (reduced/oxidized species). Significantly, the selected region of the mid-IR spectrum can be utilized to follow the actual trapping process of electrons by detecting the negative appearance of the mid-IR transient signal, which is likely due to the formation of emissive trap states. We also figure out that similar measurements in the visible region could not be monitored due the energy of the probed light that can liberate the trapped carriers into higher excitation levels, providing additional complexity to distinct between tarped carriers and other species such as excitons and free carriers absorption. Interestingly, these emissive trap states in the mid-IR can be controlled by film quality, film chemical composition, and utilized band-gap excitation energy. This work will open frontiers toward understanding and controlling the nature of trapping centers in perovskite films, along with the potential of iodide-based perovskite films to generate emission in the mid-IR range.

Methods

Film preparations

Preparing the perovskite films: the CaF2 substrates were cleaned with DI water, acetone, and IPA, followed by a 10 min UV ozone treatment. FAPbBr3 and FAPbI3 thin films were prepared using a modified antisolvent dripping technique52. 1.1 M of FAX and PbX2 were dissolved in DMF:DMSO (9:1 ratio), and 100 µl of the solution was spin-coated for 15 s at 4000 rpms. 300 µl of toluene was drop-casted during the sixth second, and the films were annealed immediately after the spin-coating process for 10 min at 170° for FAPbI3 and 100° for FAPbBr3.

Femtosecond transient absorption setup

Briefly, an excitation wavelength of 410–520 nm was utilized, while the probe light was also changing from 4000 nm to 6000 nm. The power used for the excitation wavelength depends on the utilized wavelength but was changing from ca. 100–300 μW28,37,53,54,55. The mid-IR light was detected on a N2-cooled CCD that is sensitive to mid-IR photons.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon request (A.M.El-Z. & O.F.M.).

References

Alarousu, E. et al. Ultralong Radiative States in Hybrid Perovskite Crystals: Compositions for Submillimeter Diffusion Lengths. JPCL 8, 4386–4390 (2017).

Guo, Z. et al. Long-Range Hot-Carrier Transport in Hybrid Perovskites Visualized by Ultrafast Microscopy. Science 356, 59–62 (2017).

Zuo, Z. Y. et al. Enhanced Optoelectronic Performance on the (110) Lattice Plane of an MAPbBr3 Single Crystal. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 684–689 (2017).

Bi, D. et al. Efficient Luminescent Solar Cells Based on Tailored Mixed-Cation Perovskites. Sci. Adv. 2, 1–7 (2016).

Kadro, J. M. et al. Proof-of-Concept for Facile Perovskite Solar Cell Recycling. Energ. Environ. Sci. 9, 3172–3179 (2016).

Colella, S., Mazzeo, M., Rizzo, A., Gigli, G. & Listorti, A. The Bright Side of Perovskites. JPCL 7, 4322–4334 (2016).

Zhai, Y. X., Sheng, C. X., Zhang, C. & Vardeny, Z. V. Ultrafast Spectroscopy of Photoexcitations in Organometal Trihalide Perovskites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 1617–1627 (2016).

Shi, D. et al. Low Trap-State Density and Long Carrier Diffusion in Organolead Trihalide Perovskite Single Crystals. Science 347, 519–522 (2015).

Huang, J., Shao, Y. & Dong, Q. Organometal Trihalide Perovskite Single Crystals: A Next Wave of Materials for 25% Efficiency Photovoltaics and Applications Beyond? JPCL 6, 3218–3227 (2015).

Fang, H. H. et al. Photophysics of Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Lead Iodide Perovskite Single Crystals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 2378–2385 (2015).

Green, M. A. & Bein, T. Photovoltaics Perovskite Cells Charge Forward. Nat. Mater. 14, 559–561 (2015).

Gao, P., Gratzel, M. & Nazeeruddin, M. K. Organohalide Lead Perovskites for Photovoltaic Applications. Energ. Environ. Sci. 7, 2448–2463 (2014).

Stranks, S. D. et al. Electron-Hole Diffusion Lengths Exceeding 1 Micrometer in an Organometal Trihalide Perovskite Absorber. Science 342, 341–344 (2013).

Jena, A. K., Kulkarni, A. & Miyasaka, T. Halide Perovskite Photovoltaics: Background, Status, and Future Prospects. Chem. Rev. 119, 3036–3103 (2019).

Sarmah, S. P. et al. Double Charged Surface Layers in Lead Halide Perovskite Crystals. Nano Lett. 17, 2021–2027 (2017).

Pan, J. et al. Halogen Vacancies Enable Ligand‐Assisted Self‐Assembly of Perovskite Quantum Dots into Nanowires. Angew. Chem. 131, 16223–16227 (2019).

Zhumekenov, A. A. et al. Reduced Ion Migration and Enhanced Photoresponse in Cuboid Crystals of Methylammonium Lead Iodide Perovskite. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 52, 054001 (2018).

Meggiolaro, D. et al. Iodine Chemistry Determines the Defect Tolerance of Lead-Halide Perovskites. Energ. Environ. Sci. 11, 702–713 (2018).

Fang, H.-H. et al. Ultrahigh Sensitivity of Methylammonium Lead Tribromide Perovskite Single Crystals to Environmental Gases. Sci. Adv. 2, 1–9 (2016).

Munson, K. T., Kennehan, E. R., Doucette, G. S. & Asbury, J. B. Dynamic Disorder Dominates Delocalization, Transport, and Recombination in Halide Perovskites. Chem 4, 2826–2843 (2018).

Munson, K. T., Grieco, C., Kennehan, E. R., Stewart, R. J. & Asbury, J. B. Time-Resolved Infrared Spectroscopy Directly Probes Free and Trapped Carriers in Organo-Halide Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 651–658 (2017).

Leblebici, S. Y. et al. Facet-Dependent Photovoltaic Efficiency Variations in Single Grains of Hybrid Halide Perovskite. Nat. Energ. 1, 1–7 (2016).

Krückemeier, L., Krogmeier, B., Liu, Z., Rau, U., Kirchartz, T. Understanding Transient Photoluminescence in Halide Perovskite Layer Stacks and Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2003489 (2021).

Simpson, M. J., Doughty, B., Yang, B., Xiao, K. & Ma, Y.-Z. Imaging Electronic Trap States in Perovskite Thin Films with Combined Fluorescence and Femtosecond Transient Absorption Microscopy. JPCL 7, 1725–1731 (2016).

Yamakata, A., Ishibashi, T. & Onishi, H. Time-Resolved Infrared Absorption Spectroscopy of Photogenerated Electrons in Platinized TiO2 Particles. Chem. Phys. Lett. 333, 271–277 (2001).

Guo, P. J. et al. Infrared-Pump Electronic-Probe of Methylammonium Lead Iodide Reveals Electronically Decoupled Organic and Inorganic Sublattices. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–8 (2019).

Yin, J. et al. Point Defects and Green Emission in Zero-Dimensional Perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 5490–5495 (2018).

Abdellah, M. et al. Time-Resolved Ir Spectroscopy Reveals a Mechanism with TiO2 as a Reversible Electron Acceptor in a TiO2–Re Catalyst System for CO2 Photoreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1226–1232 (2017).

Asbury, J. B. et al. Femtosecond Ir Study of Excited-State Relaxation and Electron-Injection Dynamics of Ru(Dcbpy)(2)(Ncs)(2) in Solution and on Nanocrystalline TiO2 and Al2O3 Thin Films. J. Phys. Chem. B 103, 3110–3119 (1999).

Furube, A. et al. Near-Ir Transient Absorption Study on Ultrafast Electron-Injection Dynamics from a Ru-Complex Dye into Nanocrystalline In2o3 Thin Films: Comparison with SnO2, ZnO, and TiO2 Films. J. Photoch. Photobio. A 182, 273–279 (2006).

Ellingson, R. J. et al. Dynamics of Electron Injection in Nanocrystalline Titanium Dioxide Films Sensitized with [Ru(4,4 ‘-Dicarboxy-2,2 ‘-Bipyridine)(2)(Ncs)(2)] by Infrared Transient Absorption. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 6455–6458 (1998).

El-Zohry, A. M. The Origin of Slow Electron Injection Rates for Indoline Dyes Used in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Dyes Pigm. 160, 671–674 (2019).

El-Zohry, A. M. & Karlsson, M. Gigantic Relevance of Twisted Intramolecular Charge Transfer for Organic Dyes Used in Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 23998–24003 (2018).

Juozapavicius, M. et al. Evidence for “Slow” Electron Injection in Commercially Relevant Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells by Vis-Nir and Ir Pump-Probe Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 25317–25324 (2013).

Juozapavicius, M., Kaucikas, M., van Thor, J. J. & O’Regan, B. C. Observation of Multiexponential Pico- to Subnanosecond Electron Injection in Optimized Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells with Visible-Pump Mid-Infrared-Probe Transient Absorption Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 116–123 (2012).

Ghosh, H. N., Asbury, J. B. & Lian, T. Q. Direct Observation of Ultrafast Electron Injection from Coumarin 343 to TiO2 Nanoparticles by Femtosecond Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 6482–6486 (1998).

El-Zohry, A. M. & Zietz, B. Electron Dynamics in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Influenced by Dye-Electrolyte Complexation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 16300–16307 (2020).

Furube, A., Du, L., Hara, K., Katoh, R. & Tachiya, M. Ultrafast Plasmon-Induced Electron Transfer from Gold Nanodots into TiO2 Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 14852–14855 (2007).

Pavliuk, M. V. et al. Magnetic Manipulation of Spontaneous Emission from Inorganic Cspbbr3 Perovskites Nanocrystals. Adv. Optical Mater. 4, 2004–2008 (2016).

Cieslak, A. M. et al. Ultra Long-Lived Electron-Hole Separation within Water-Soluble Colloidal ZnO Nanocrystals: Prospective Applications for Solar Energy Production. Nano Energy 30, 187–192 (2016).

Harrick, N. J. Lifetime Measurements of Excess Carriers in Semiconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 27, 1439–1442 (1956).

Tang, J. et al. Colloidal-Quantum-Dot Photovoltaics Using Atomic-Ligand Passivation. Nat. Mater. 10, 765–771 (2011).

Tamaki, Y. et al. Trapping Dynamics of Electrons and Holes in a Nanocrystalline TiO2 Film Revealed by Femtosecond Visible/near-Infrared Transient Absorption Spectroscopy. Comptes Rendus Chim. 9, 268–274 (2006).

Heimer, T. A. & Heilweil, E. J. Direct Time-Resolved Infrared Measurement of Electron Injection in Dye-Sensitized Titanium Dioxide Films. J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 10990–10993 (1997).

Guo, P. J. et al. Slow Thermal Equilibration in Methylammonium Lead Iodide Revealed by Transient Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–9 (2018).

El-Zohry, A. M., Cong, J., Karlsson, M., Kloo, L. & Zietz, B. Ferrocene as a Rapid Charge Regenerator in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Dyes Pigm. 132, 360–368 (2016).

Barker, A. J. et al. Defect-Assisted Photoinduced Halide Segregation in Mixed-Halide Perovskite Thin Films. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1416–1424 (2017).

Samu, G. F., Janáky, C. & Kamat, P. V. A Victim of Halide Ion Segregation. How Light Soaking Affects Solar Cell Performance of Mixed Halide Lead Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1860–1861 (2017).

Chen, Y. H. et al. Impacts of Alkaline on the Defects Property and Crystallization Kinetics in Perovskite Solar Cells. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–9 (2019).

Ghosh, S., Pal, S. K., Karki, K. J. & Pullerits, T. Ion Migration Heals Trapping Centers in CH3NH3PbBr3 Perovskite. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 2133–2139 (2017).

Kamat, P. V. & Kuno, M. Halide Ion Migration in Perovskite Nanocrystals and Nanostructures. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 520–531 (2021).

Jeon, N. J. et al. Solvent Engineering for High-Performance Inorganic–Organic Hybrid Perovskite Solar Cells. Nat. Mater. 13, 897 (2014).

Hussain, M. et al. Spin–Orbit Charge-Transfer Intersystem Crossing of Compact Naphthalenediimide-Carbazole Electron-Donor–Acceptor Triads. J. Phys. Chem. B 125, 10813–10831 (2021).

Imran, M. et al. Intersystem Crossing Via Charge Recombination in a Perylene-Naphthalimide Compact Electron Donor/Acceptor Dyad. J. Mater. Chem. C. 8, 8305–8319 (2020).

El-Zohry, A. M. Excited-State Dynamics of Organic Dyes in Solar Cells. In Solar Cells - Theory, Materials and Recent Advances, https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.94132 (IntechOpen, London, 2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank for the financial support provided by KASUT to carry out this work.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.El-Z. designed the concept of the paper, measured the mid-IR data wrote the paper, and put the overall scheme. B.T. and A.A. prepared the perovskite films and revised the paper. P.M. performed the transient data in the visible range along with revising the paper. O.M.B. supervised the project and revised the paper. B.S.O. supervised the project and revised the paper. O.F.M. supervised the project and revised the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Zohry, A.M., Turedi, B., Alsalloum, A. et al. Ultrafast transient infrared spectroscopy for probing trapping states in hybrid perovskite films. Commun Chem 5, 67 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-022-00683-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-022-00683-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.