Abstract

Aqueous organic redox flow batteries (AORFBs) hold great promise as low-cost, environmentally friendly and safe alternative energy storage media. Here we present aqueous organometallic and all-organic active materials for RFBs with a water-soluble active material, sulfonated tryptanthrin (TRYP-SO3H), working at a neutral pH and showing long-term stability. Electrochemical measurements show that TRYP-SO3H displays reversible peaks at neutral pH values, allowing its use as an anolyte combined with potassium ferrocyanide or 4,5-dihydroxy-1,3-benzenedisulfonic acid disodium salt monohydrate as catholytes. Single cell tests show reproducible charge-discharge cycles for both catholytes, with significantly improved results for the aqueous all-organic RFB reaching high cell voltage (0.94 V) and high energy efficiencies, stabilized during at least 50 working cycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global and economic population growth impels the increase of energy consumption. Resources formed over hundreds of millions of years have been burned in a relatively short time, with substantial environmental impact1,2. To reduce the use of fossil fuels, and environmentally friendly route to generate and store electricity from renewable sources is needed to fulfill the world’s needs in a sustainable way2,3,4,5,6,7.

In the past recent years, renewable energy technologies have therefore attracted much scientific and public interest8. Traditional batteries such as lithium-ion batteries are of widespread use, but they cannot cost-effectively store, enough energy for the long discharge durations at rated power, they use flammable organic electrolytes and reveal high maintenance costs8,9,10.

Redox flow batteries (RFBs) are an emerging and highly promising power source, representing one of the best storage technologies for electrical energy that is obtained from renewable sources like wind power and solar energy11. RFBs are frequently described as affordable, reliable (with extremely long charge/discharge cycle life) and eco-friendly depending on the materials used5,12,13,14,15. Aqueous organic redox flow batteries (AORFBs) have been recently proposed as low-cost and alternatives to metal-based RFBs technology5,8,9,10,16,17,18,19. These AORFBs have several outstanding advantages mainly because of their prospect of offering such a grid-scale energy storage solution20. In addition, AORFBs are more environmentally friendly and safe since they use nonflammable aqueous redox-active electrolytes9,21.

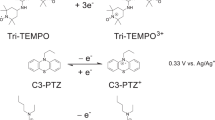

In the last years, novel AORFBs designs have been proposed essentially based on different electrolytes8,9,10,15,22,23. The use of anthraquinones has gained popularity since these quinones are well-known redox-active molecules with electrochemical reversibility and fast reactions rates9,16,24,25,26,27. However, and in particular, at alkaline media, this family of compounds still seems rather unstable and most of the RFBs cannot meet requirements for practical application8. To overcome the limitation of the corrosive electrolytes (acidic or alkaline media), the development of neutral aqueous RFBs has emerged over the years9,20,25,28,29. Neutral AORFBs are more ecofriendly and have outstanding advantages with noncorrosive electrolytes and inexpensive simple salts (e.g., KCl and NaCl) as supporting electrolytes. In addition, neutral pH electrolytes suppress undesired side reactions for active species caused by protons and hydroxides at acidic and alkaline conditions28,30. So far methyl viologen (MV) aqueous RFBs have demonstrated the most stable cycling performances in neutral media19,28,29,31. Typically MV is employed as anolyte and ferrocene or (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl (TEMPO) derivatives as catholyte to develop high-voltage and stable pH neutral aqueous RFBs19,29,30.

Therefore, the search and development of new water-soluble active materials for the improvement of neutral pH battery storage systems is increasingly significant and will continue to growth in the future. Tryptanthrin (TRYP) and its derivatives are a surprising family of compounds with biological and pharmacological activities32,33,34,35,36,37,38 with the addition of displaying interesting redox properties due to the electron-accepting ability of the TRYP structure39,40. TRYP can be synthetically obtained from indigo, one of the most stable organic dyes41,42,43,44. TRYP shows two reversible waves with cathodic and anodic peaks, indicating two one-electron transfers35,39. Similar redox properties have also been reported for some azulene and benzo-annulated tryptanthrin derivatives45,46.

In the effort to obtain new active materials presenting long-term stability for AORFBs, a water-soluble tryptanthrin, tryptanthrin sulfonic acid (TRYP-SO3H), was synthesized and further tested with a home-built RFB set-up (Supplementary Fig. SI1). Electrochemical measurements at several pH values, with determination of the kinetic parameters, diffusion coefficient, and electron transfer rate constant, for TRYP-SO3H at neutral pH values, were obtained. Charge–discharge processes and cell performance at neutral pH of (i) aqueous organometallic active materials and (ii) of all-organic active materials for RFB, combining this water-soluble tryptanthrin as the negative electrolyte (anolyte) with (i) potassium ferrocyanide and (ii) 4,5-dihydroxy-1,3-benzenedisulfonic acid disodium salt monohydrate (BQDS) as the positive electrolytes (catholyte), were evaluated.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization

Aiming the preparation of a water-soluble tryptanthrin derivative, a similar synthetic approach to the one reported by Pereira et al.47 was followed. The chlorosulfonation of TRYP through electrophilic aromatic substitution with neat chlorosulfonic acid at 60 °C during 48 h under vigorous stirring and nitrogen atmosphere gave rise, after isolation, to a dark green solid, Fig. 1. The proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectrum of the reaction crude (Supplementary Fig. SI2), although with some unreacted TRYP (confirmed by TLC analysis), shows the peak around 8.70 ppm characteristic of hydrogen at the ortho position in this aromatic moiety, confirming that the electrophilic aromatic substitution take place at the position 8 or 2 of TRYP. Hydrolysis of the chlorosulfonation products in water, yield the desired tryptanthrin sulfonic acid derivatives. As expected, knowing that 2- and 8-positions of TRYP are activated for electrophilic aromatic substitution, being the 8-position more reactive than the 2-position48, two isomers were obtained. The 1H NMR spectrum showed seven major peaks corresponding to seven hydrogen atoms, indicating that mono-substitution of TRYP occurs (Supplementary Fig. SI3). From the doublets at 8.69 and 8.67 ppm it is possible to calculate the isomer ratio with 85% of TRYP-8SO3H and 15% of TRYP-2SO3H. These results were further confirmed by high-performance liquid chromatography with a diode-array detector (HPLC-DAD) analysis (Supplementary Fig. SI4). The chromatogram showed two products with very similar polarity with retention times of 29.5 and 31.9 min and the percentage of total chromatogram integration of 72% and 14%, respectively (Supplementary Table SI1). Three independent experiments carried out following the described experimental procedure afford the final mixture of isomers in the same ratio (Supplementary Fig. SI5). The infrared (IR) spectrum shows bands at 775, 1200, 1220, and 1350 cm−1 characteristic of hydrated sulfonic acid groups (Supplementary Fig. SI6). The compound was further characterized by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and the obtained data were in agreement with the formula proposed m/z [M − 1]− = 327.0081 calculated for C15H7N2O5S; found: 327.0078 (Supplementary Fig. SI7). The solvent-free methodology allows the synthesis of the water-soluble tryptanthrin-based active material in good yields and high purity.

Tryptanthrin sulfonic acid—cyclic voltammetry

Since there are only a few studies describing the redox properties of TRYP39,40, the electrochemical behavior of this compound was initially performed by measuring cyclic voltammetry (CV) of TRYP in acetonitrile (MeCN) using 0.1 M of tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (NBu4PF6) as a supporting electrolyte. CV revealed two reversible peaks in the cathodic region and two reversible peaks in the anodic region, even after several scans, see Supplementary Fig. SI8. The reversible waves are separated by approximately 60 mV and these results are in agreement with previous studies35,39.

To evaluate the electrochemical behavior of the water-soluble tryptanthrin sulfonic acid derivative (TRYP-SO3H), CV measurements in an aqueous medium were obtained at different pH values. CVs are presented in Supplementary Fig. SI9 and the relevant electrochemical data, extracted from these, including the oxidation (Epa) and reduction (Epc) potentials, summarized in Table 1. The CVs obtained showed, at pH = 0, the occurrence of one reversible reduction peak at 0.034 V and one reversible oxidation peak at 0.097 V (Supplementary Fig. SI9a). At pH = 7, a similar behavior was also observed, with one cathodic peak at −0.507 V and one anodic peak at −0.406 V (Supplementary Fig. SI9b). The CV experiment at pH = 13 displays three peaks in the anodic region and three peaks in the cathodic region (Supplementary Fig. SI9c). From the obtained results it is visible that TRYP-SO3H presents high reversible redox behavior at acidic and neutral pH, a mandatory condition for its use in aqueous RFBs.

In recent years, the development of neutral pH aqueous RFBs have stood out as promising RFBs technology for sustainable and safe energy storage9,20,28,29. One of the reasons is that neutral pH-based electrolytes are less-corrosive19,29,49,50 and more eco-friendly when compared with the acidic or alkaline electrolytes that suffer from corrosion problems in cell stacks4,13,51.

Redox couples as active species in neutral pH aqueous redox flow battery cell tests

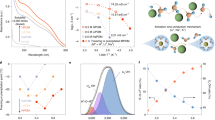

To evaluate the viability of the redox couples consisting of TRYP-SO3H/K4[Fe(CN)6] and TRYP-SO3H/BQDS as the active species at neutral pH in the aqueous organometallic and all-organic active materials for RFB, the redox reactivity was obtained from CVs (Fig. 2). Potassium ferrocyanide was chosen as catholyte due to the strong coordination of cyanide ions to the iron center, which makes the standard [Fe(CN)6]4−/[Fe(CN)6]3− redox couple highly stable52 and nontoxic19. In addition, this redox couple also showed ultra-stable cycling performance at neutral conditions, thus being more suitable for application in aqueous RFBs53. BQDS is an aromatic organic compound that belongs to the family of quinones and in recent years has been used as the positive active material in aqueous RFBs26,54. Due to a relatively high electrode potential (0.76 V)26 and high solubility in sulfuric acid (0.65 M in 1.0 M H2SO4)55, most of the reported studies with BQDS are in acidic medium. Our studies showed high solubility in KCl (1.28 M in 1.0 M KCl, see Supplementary Table SI2) and high electrode potential (0.94 V in KCl), demonstrating that BQDS can be viable as positive active material at neutral pH.

From Fig. 2a, it is possible to observe that the cell voltage of the redox reaction of K4[Fe(CN)6] and TRYP-SO3H vs. Ag/AgCl is, at neutral pH, +0.27 V and −0.46 V, respectively, giving an expected cell potential of 0.73 V for the TRYP-SO3H/K4[Fe(CN)6] redox couple. Compared with the well-known organic anolyte anthraquinone-2,7-disulfonic acid (2,7-AQDS), in neutral media, TRYP-SO3H shows an identical cell potential: 0.76 V25 vs. 0.73 V (this work). This demonstrates that TRYP-SO3H can, when compared to quinone-type compounds, be considered viable as the active species for the anolyte. When the all-organic redox couple TRYP-SO3H/BQDS (Fig. 2b) is used the cell voltage of BQDS vs. Ag/AgCl is 0.48 V, enhancing the positive shift in the redox potential and thus achieving a higher cell potential (0.94 V) when compared with K4[Fe(CN)6].

To further verify the correlation between the reaction rate of the catholyte/anolyte pair with the performance and stability of the RFBs, the kinetic parameters, diffusion coefficient (D), and electron transfer rate constant (kο), were quantified. The Randles–Sevcik equation56 (Eq. 1) was used to calculate the diffusion coefficient (D in cm2 s−1)

where, ip is the cathodic or anodic peak current, n is the number of electrons, F the Faraday’s constant (C mol−1), A is the electrode surface area (in cm2), C0 is the concentration of the oxidative or reductive species (mol cm−3), R the ideal gas constant (J K−1 mol−1), T the temperature (K) and υ is scan rate in V s−1. To measure the diffusion coefficients of the K4[Fe(CN)6]/TRYP-SO3H and BQDS/TRYP-SO3H redox couples, CV experiments together with the plot of the peak current ip as a function of the square root of the scan rate υ1/2 (Fig. 3) are needed to obtain the Randles–Sevcik equation parameters. A linear fit (ip = slope × υ1/2) yields the slope of the cathodic and anodic peaks from which the diffusion coefficient can be obtained (experimental details in Supplementary Tables SI3–SI5).

Cyclic voltammetry scan rate study obtained with saturated N2 at various scan rates (10–100 mV s−1) in 1.0 M KCl solution of electrolyte. a 1.0 mM TRYP-SO3H at various scan rates. b plot of ipa and ipc over the square root of scan rates for 1.0 mM TRYP-SO3H. c 1.0 mM K4[Fe(CN)6]·3H2O at various scan rates. d plot of ipa and ipc over the square root of scan rates for 1.0 mM K4[Fe(CN)6]·3H2O. e 1.0 mM BQDS at various scan rates. f plot of ipa and ipc, over the square root of scan rates for 1.0 mM BQDS. In b, d, and f black squares and line for oxidative reaction and red squares and line for reductive reaction.

The electron transfer rate constant (kο) of K4[Fe(CN)6]/TRYP-SO3 and BQDS/TRYP-SO3 redox couples were also estimated by using the Nicholson method using the D values previously obtained57. The relationship between the kο and the Nicholson dimensionless number (Ψ) is given by Eq. 2

Using BQDS (1.0 mM), the D and kο values (5.38 × 10−7 and 2.71 × 10−4 cm s−1) were close to those obtained for TRYP-SO3H (6.98 × 10−8 and 3.62 × 10−4 cm s−1) when compared to the rate constants values for K4[Fe(CN)6] (6.63 × 10−6 and 1.24 × 10−2 cm s−1), see experimental details in Supplementary Tables SI6–SI8. The electron transfer rate constant for TRYP-SO3H is in the range found for quinones and anthraquinones used in aqueous RFBs9. This shows that despite some differences in the diffusion coefficients and of the rate constants of the redox couples, both redox pairs are suitable as active materials for aqueous organometallic and all-organic RFBs. Based on the above results, both organometallic and all-organic redox couples were tested in a cell stack.

Neutral pH aqueous redox flow battery cell tests

Two single cells were assembled to evaluate the properties of the TRYP-SO3H/K4[Fe(CN)]6 and TRYP-SO3H/BQDS redox pairs for aqueous organometallic and all-organic active materials for RFB working at neutral pH (Fig. 4). Solubility measurements showed that TRYP-SO3H has a solubility of approximately 0.12 M in 1.0 M KCl at 293 K (see Supplementary Table SI2). Therefore, the concentration of active materials used is relatively low to avoid the possible precipitation of active materials during cycling. Representative galvanostatic charge–discharge curves for fifty complete cycles of the flow cells obtained for the TRYP-SO3H/K4[Fe(CN)6] and TRYP-SO3H/BQDS couples with a current density applied of 5.2 and 2.6 mA cm−2, respectively, are shown in Fig. 5. The current densities were limited to low values due to resistance of the electrolyte to avoid excess ohmic loss. The cells can be charged and discharged within the selected potential window (the cut-off potential set between 0.2 and 1.2 V for TRYP-SO3H/K4[Fe(CN)6] and between 0.5 and 1.5 V for TRYP-SO3H/BQDS) with reproducible cycles. The charge–discharge profiles for the two RFB are slightly different. Indeed, whereas with the TRYP-SO3H/K4[Fe(CN)6 redox couple the interval period between charging and discharging is longer for the first cycle than it is for the others (Fig. 5a), with the TRYP-SO3H/BQDS redox couple all charge–discharge cycle are identical (Fig. 5b) and stable from the first cycle till the end of the cell test of ~29 h (50 cycles). It is also noticeable that the charging and discharging time using the all-organic active materials is four times longer than with the organometallic active materials (see Supplementary Fig. SI10).

Representative galvanostatic charge–discharge curves of neutral pH aqueous organometallic and all-organic active materials for RFB single cells using 5.0 mM of TRYP-SO3H in 1.0 M KCl solution as supporting electrolyte measured at the third cycle. a 10.0 mM of K4[Fe(CN)6]·3H2O as catholyte. b 5.0 mM of BQDS as catholyte.

The obtained average discharge energy density and average discharge capacity of the organometallic active materials cell were 0.014 Wh L−1 and 1.17 mAh, respectively, while that of the all-organic TRYP-SO3H/BQDS redox couple is highest, with values of 0.046 Wh L−1 and 2.65 mAh. Long-time capacity stability is a vital characteristic for aqueous RFBs. Indeed, while for the organometallic active materials cell (Fig. 6a) during fifty complete cycles (~7 h) there is a decrease in the charge and discharge energy density and capacity, with capacity retention falling to 38% of its original value (6.309–2.409 C) over fifty cycles (see Supplementary Fig. SI11a). In general, non-capacity-related coulombic efficiency loss (capacity fades over the cycles but coulombic efficiency increases, Supplementary Fig. SI11a) mainly arises from electrolyte side reactions58. In the all-organic active materials cell (Fig. 6b) the values steadily increase until ~10 cycles and further stabilizes to a total number of fifty cycles (~29 h). Stable capacity retention was observed with more than 98% total capacity retention after forty cycles (Supplementary Fig. SI11b).

The coulombic, voltaic, and energetic efficiencies of the aqueous organometallic and all-organic active materials vs. the number of cycles in the flow cell are shown in Fig. 7. Coulombic and voltage efficiencies are the properties that better evaluate the performance of RFBs. For the neutral pH aqueous organometallic active materials RFB (Fig. 7a) the values found for coulombic, voltaic, and energetic efficiencies were 80%, 57%, and 46%, respectively. In the all-organic active materials cell, the obtained values were higher, displaying an interesting cycling performance with 89% coulombic efficiency, 75% of voltaic efficiency, and 67% of energy efficiency. It can be seen that at neutral pH the aqueous all-organic active materials flow cell presents notable cycling retention (98%) and coulombic efficiencies above ~90% through several cycles (see Supplementary Fig. SI11b).

Coulombic efficiency, voltaic efficiency, and energetic efficiency plots of neutral pH aqueous organometallic and all-organic active materials for RFB single cells using 5.0 mM of TRYP-SO3H in 1.0 M KCl as supporting electrolyte. a 10.0 mM of K4[Fe(CN)6]·3H2O as catholyte. b 5.0 mM of BQDS as catholyte.

In order to quantify the electrochemical stability of the active materials and to evaluate the possibility of crossover or chemical degradation of the aqueous organometallic and all-organic active materials for RFB during cycling, electrochemical impedance spectra were measured before and after charge–discharge cycles, see Figs. 8 and 9. From the voltaic efficiency, it is possible to assess losses through electrolyte crossover59. During the cell test, there were no vestiges of crossover through the membrane. After the cell measurement, the CV measurement performed to the catholyte (K4[Fe(CN)6]) (Fig. 8a) does not differ from the initial one (Fig. 2) and no peaks in the CV of the K4[Fe(CN)6] electrolyte in the range of the CV of TRYP-SO3H (see Supplementary Fig. SI12) could be observed. According to Fig. 8b, and after full cell tests, a change in the voltammogram profile of TRYP-SO3H is seen, with the peak maxima shifting to more negative potentials together with new anodic and cathodic peaks. These results may help to explain the changes observed in the values of the charge–discharge cycles with time, as well as the observed battery capacity loss, which is likely related to some chemical modification of TRYP-SO3H after 50 cycles. From Fig. 9a, it is visible that the cyclic voltammetry curves of the BQDS electrolyte, obtained before and after the charge–discharge studies, are also different. After finalizing the experiment with the RFB, the BQDS showed an additional redox peak. The instability of BQDS has already been reported in an acidic medium, where this compound can undergo a Michael addition reaction with water leading to trihydroxybenzene derivatives17,54,55,60. This reaction may also explain the obtained results at neutral pH values which is further reflected in the capacity decrease. According to Fig. 9b, before cycling, the TRYP-SO3H electrolyte has a current intensity of the reduction and oxidation peak much higher than after fifty charge–discharge cycles indicating loss of reversibility.

Crossover through the membrane was also investigated. After the charge–discharge experiment ended, no peaks in the cyclic voltammogram of the BQDS electrolyte, in the range of the TRYP-SO3H peaks, could be observed (see Supplementary Fig. SI13), indicating the absence of crossover of the TRYP-SO3H electrolyte. Another possibility for the capacity fading is the leakage from the cell stack system. After cell cycling, both cells were disassembled and no coloration was found on the gaskets, indicating the absence of electrolyte leakage.

According to the results, the all-organic TRYP-SO3H/BQDS redox couple showed better battery performance than the organometallic TRYP-SO3H/K4[Fe(CN)6] redox couple, confirming the role of BQDS in the promotion of the electrochemical performance of the cell.

In order to study the effect of the concentration of the all-organic active materials in the stability and performance of the RFB, the concentration of the redox pair was increased to 0.1 M, a concentration close to the solubility limit of TRYP-SO3H (0.12 M in 1.0 M KCl, see Supplementary Table SI2). The data is presented in Figs. 10 and 11 and can be summarized as follows: (i) with the augment on the concentration of TRYP-SO3H and BQDS, the active materials remain well dissolved (see Supplementary Table SI2) and operated well during 50 cycles (Fig. 10); (ii) as the concentration of TRYP-SO3H and BQDS increased, the coulombic efficiency reaches 95% (Fig. 11); (iii) with 0.1 M of active materials, the discharge energy density and capacity values are, however, lower (Fig. 12) when compared with the highest values displayed by other systems working at neutral pH values19,20,28,50,61. The rise of the ohmic resistance and viscosity of the redox couple with the concentration may explain the results obtained.

Conclusions

In the search for new water-soluble active materials for aqueous RFBs, the use of a water-soluble tryptanthrin (TRYP-SO3H), was found to be a promising approach for sustainable development for these applications. CV measurements in an aqueous medium showed that TRYP-SO3H exhibits high redox reversibility with particular emphasis at neutral pH values. As a result, two cells, organometallic and all-organic, were assembled by using TRYP-SO3H as anolyte and K4[Fe(CN)6] and BQDS as catholyte. At neutral pH values both organometallic and all-organic RFBs display promising results; yet, the all-organic TRYP-SO3H/BQDS RFB demonstrates significant improvement in the performance and merit of the cell, with higher average coulombic (89%), voltaic (75%), and energy (67%) efficiencies and stable charge–discharge curves during ~29 h. The present study highlights a new perspective on screening water-soluble tryptanthrin derivatives as organic active materials and underlines the possibility to develop low-cost and environmentally friendly AORFBs (working at neutral pH) using sustainable redox-active organic molecules.

Methods

Chemicals

Tryptanthrin (TRYP) was synthesized following the methodology recently reported by our group41,62. Chlorosulfonic acid (ClSO3H) was purchased from Merck, sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), potassium ferricyanide (K3[Fe(CN)6]) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were purchased from José Manuel Gomes dos Santos Lda, potassium ferrocyanide (K4[Fe(CN)6].3H2O) was purchased from Baker Analyzed Reagent, tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate and 4,5-dihydroxy-1,3-benzenedisulfonic acid disodium salt monohydrate (BQDS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, potassium chloride (KCl) was purchased from Panreac, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was purchased from Valente e Ribeiro Lda and sulfuric acid (H2SO4) from Labkrem. All the reagents were used without further purification. The solvents, pro analysis (P.A.) quality, were used as purchased. Ultra-pure water at pH = 5.4, was purified using Direct Q3 Merck Millipor equipment.

Characterization techniques

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded at room temperature in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) solutions on a Bruker Avance III spectrometer operating at 400.13 MHz for 1H. Tetramethylsilane was used as an internal standard. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was performed on a Bruker microTOF-Focus mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization time-of-flight (ESI–TOF) source. Tryptanthrin sulfonic acid was analyzed in an analytical Elite Lachrom high-performance liquid chromatography system with L-2455 diode array detector (HPLC-DAD), L-23000 column oven (stationary phase Purospher® STAR RP-18 endcapped (5 μm) column from Merck), L-2130 Pump and an L-2200 autosampler. IR spectroscopy was recorded using the Thermo Fisher Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer.

Synthetic procedure

In the synthesis, 300 mg of TRYP (1.2 mmol) was placed in a bottom flask in a paraffin bath at 60 °C. Keeping an inert atmosphere, chlorosulfonic acid (3 mL, 45 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred for 48 h. The solution was left to cool in ice and neutralized with a saturated solution of sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3). The garnet solid obtained was filtrated and washed with water and the solid was dried at 45 °C overnight to yield 173 mg of a dark green solid. NMR analysis of the reaction crude showed that the dark green solid consisted in a mixture of, tryptanthrin sulfonyl chloride and some unreacted TRYP. The dark green mixture (100 mg) was suspended in 50 mL of water and further heated at reflux for 48 h until a green solution was obtained. After cooling to room temperature, the solution was filtrated to remove a trace of non-dissolved TRYP and the solvent was evaporated under vacuum. The green solid obtained was dried at 45 °C for 24 h to yield 73 mg of a mixture of two isomers, 6,12-dioxo-6,12-dihydroindolo[2,1-b]quinazoline-8-sulfonic acid, tryptanthrin 8-sulfonic acid (TRYP-8SO3H), and 6,12-dioxo-6,12-dihydroindolo[2,1-b]quinazoline-2-sulfonic acid, tryptanthrin 2-sulfonic acid (TRYP-2SO3H) in a 85:15 ratio. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz,), δ 8.69 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.44 (ddd, J = 8.0 Hz, J = 1.6 Hz, J = 0.4 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (ddd, J = 8.4 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (m, 2H), 7.70 (dt, J = 8.4 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd, J = 8.0 Hz, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H) ppm. HRMS (ESI–TOF–MS): m/z [M − 1]− = 327.0081 calculated for C15H7N2O5S; found: 327.0078. IR (KBr pellets) wavenumber (cm−1): 775, 1200, 1220, 1350, 1430, 1590, 1680, and 1730 cm−1. HPLC-DAD: Stationary phase Purospher® STAR RP-18 endcapped (5 μm). Eluent: potassium acetate (pH = 3)(A) and MeCN:H2O (50:50)(B) (from 100:0 to 30:70(A/B v/v)); 5% increment of B each min for 12 min; 5% increment of B each 2 min until 22 min and 30:70 (A/B v/v) ratio for 12 min. The flow rate of 0.8 mL/min in the first 9 min and then 0.4 mL/min until 35 min. L-2455 Diode Array Detector (400 nm). Percentage of total chromatogram integration at retention time 29.49 min and 31.89 min of 72% and 14%, respectively.

Solubility measurements

The solubility of the active materials at room temperature was measured in 1.0 M KCl. To ascertain the solubility limit a defined amount of each compound was first weighed and transferred to a glass tube after which an increasing volume of 1.0 M KCl solution was added in intervals of 10–100 µL. After each addition, the test tube was ultrasonic for at least 10 min at room temperature. Then the tube was inspected visually for an undissolved sample and the addition of 1.0 M KCl solution continued until the sample seemed just dissolved. Dissolved samples were left to stand for ~12 h and visually inspected. The volumes just before and after the full dissolution was used to calculate the solubility interval.

Cyclic voltammetry

CV experiments were carried out using an Autolab potentiostat/galvanostat PGSTAT204 running with NOVA 2.1 software and a three-electrode system in a one-compartment electrochemical cell with a capacity of 10 mL. A glassy carbon electrode (GCE) (d = 3 mm) was the working electrode, GC (d = 1.6 mm) wire the counter electrode, and Ag/Ag+ (0.01 M silver nitrate (AgNO3) in 0.1 M tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (NBu4PF6) in MeCN) the reference electrode for nonaqueous solutions. In an aqueous medium Ag/AgCl (3.0 M KCl) was the reference electrode. The GCE was polished with appropriate polishing pads using first aluminum oxide particle size 0.3 μm and then aluminum oxide particle size 0.075 μm (polish in a Fig. 8 motion) before each electrochemical experiment. After polishing, the electrode was rinsed thoroughly with Milli-Q water and the electrode was sonicate in a container with Milli-Q water and ethanol (50:50 v/v) for 5 min. Following this mechanical treatment, the GCE was placed in buffer supporting electrolyte, and differential pulse voltammograms were recorded until a steady-state baseline voltammogram was obtained. This procedure ensured very reproducible experimental results.

TRYP sample was dissolved in 10 mL of acetonitrile (MeCN) with 0.1 M of NBu4PF6 as the supporting electrolyte. The compound was prepared at a concentration of 1.0 mM and was degassed with nitrogen for 10 min prior to analysis. A solution of 1.0 mM of ferrocene with 0.1 M of NBu4PF6 in 10 mL of MeCN was used as standard and also degassed with nitrogen for 10 min prior to analysis. An atmosphere of nitrogen was maintained during the voltammetric experiment and the sample was run at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1.

To evaluate open-circuit voltage (OCV) between TRYP-SO3H and K3[Fe(CN)6] at different pH values, the solutions were prepared at a concentration of 2.0 mM and degassed with nitrogen for 10 min prior to analysis. Depending on the pH experiments different electrolytes were used, for pH = 0 (1.0 M H2SO4) solution, for pH = 7 (1.0 M KCl) solution, and pH = 13 (1.0 M NaOH) solution. Potassium ferricyanide (K3[Fe(CN)6]·3H2O) (1.0 mM solution) with 1.0 M of the proper electrolyte in 10 mL of Milli-Q water was used as standard and also degassed with nitrogen for 10 min prior to analysis. Lastly, to measure the OCV for BQDS, 1.0 mM was dissolved into 1.0 M KCl solution. An atmosphere of nitrogen was maintained during the voltammetric experiments and the samples were run at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1.

For the determination of the kinetic parameters, such as diffusion coefficient (D) and electron transfer rate constant (kο), a solution of TRYP-SO3H (1.0 mM) was dissolved in 10 mL of Milli-Q water with 1.0 M KCl as the supporting electrolyte. First, a solution of 1.0 mM of K4[Fe(CN)6] with 1.0 M of KCl in 10 mL of Milli-Q water was used as catholyte. Second, the catholyte was prepared by dissolving 1.0 mM of BQDS into 10 mL of 1.0 M KCl solution. All the solutions were degassed with nitrogen for 10 min prior to analysis. An atmosphere of nitrogen was maintained during the voltammetric experiments and the samples were run at a scan rate of 10–100 mV s−1 range. All the CV experiments were carried out at T = 293 K.

Cell test measurements

The flow cell for the aqueous RFBs was assembled with two steel end frame plates and two copper current collectors, held in place using two carbon electrolyte chambers. Graphite foil was used to form a flexible interconnect to the copper end-plate. Ethylene propylene diene monomer rubber gaskets were positioned on top of the carbon plate and the carbon felt electrodes (Alfa Aesar, 3.18 mm) were positioned within the gaskets. A piece of Nafion® perfluorinated membrane (Aldrich, nafion® 115) was sandwiched between carbon felts and the battery was compressed using tie-bolts. Each carbon chamber was connected with an electrolyte reservoir using a piece of Viton-type tube. The electrolyte reservoirs were 100 mL glass containers. The active area of the cell was 4 cm2. A Master® L/S® peristaltic pump (Cole-Parmer, Easy-load II, Model 77202-60) was used to press sections of Masterflex tubing to circulate the electrolytes through the electrodes at a flow rate of 30 mL min−1. Both reservoirs were purged with nitrogen to remove O2 for 30 min and an atmosphere of nitrogen was maintained during the cell cycling. The flow cell was galvanostatically charged/discharged at room temperature and measurements were carried out with a current density applied of 20 mA using 0.2 and 1.2 V cut-off potentials in the first test (TRYP-SO3H/K4[Fe(CN)6]) and a current density applied of 10 mA using 0.5 and 1.5 V cut-off potentials in the second test (TRYP-SO3H/BQDS). The charge-discharge curves were recorded using an Autolab potentiostat/galvanostat PGSTAT204 running with NOVA 2.1 software. In the flow cell experiments, it was ensured that the same number of equivalents of the catholyte and anolyte was used on both sides. The negative electrolyte was prepared by dissolving TRYP-SO3H (5.0 mM) in 50 mL of Milli-Q water with 1.0 M KCl as the supporting electrolyte. First, a solution of 10.0 mM of K4[Fe(CN)6] with 1.0 M of KCl in 50 mL of Milli-Q water was used as a positive electrolyte. Second, the catholyte was prepared by dissolving 5.0 mM of BQDS into 50 mL of 1.0 M KCl solution. Finally, the negative electrolyte was prepared by dissolving TRYP-SO3H (0.1 M) in 50 mL of Milli-Q water with 1.0 M KCl as the supporting electrolyte and the catholyte was prepared by dissolving 0.1 M of BQDS into 50 mL of 1.0 M KCl solution. All the solutions were degassed with nitrogen for 30 min prior to analysis and an atmosphere of nitrogen was maintained during cell cycling. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (T = 293 K).

Membrane treatment

The Nafion perfluorinated membrane was initially emerged in Milli-Q water at 80 °C for 15 min and then put into 5% hydrogen peroxide solution (H2O2) for 30 min to remove organic impurities. In the next step in order to cleanse the metallic impurities, the membrane was put into 0.05 M KCl solution for one hour (after 30 min the KCl solution was changed). In the last step, the membrane was put into Milli-Q water for one hour, changing the water every 15 min. After pre-treatment, the membrane was placed in Milli-Q water to avoid further contaminations.

Carbon felt thermal treatment

A piece of carbon felt was heated at 400 °C for 24 h in a muffle furnace Vulcan 3-550. Then, the temperature of the muffle furnace was lowered to room temperature and the carbon felt was removed and properly stored until further use.

References

Alotto, P., Guarnieri, M. & Moro, F. Redox flow batteries for the storage of renewable energy: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 29, 325–335 (2014).

Carretero-González, J., Castillo-Martínez, E. & Armand, M. Highly water-soluble three-redox state organic dyes as bifunctional analytes. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 3521–3530 (2016).

Khalid, A. & Awad, M. Chapter 5—Redox—Principles and Advanced Applications. (IntchOpen, 2017).

Huskinson, B. et al. A metal-free organic–inorganic aqueous flow battery. Nature 505, 195 (2014).

Liu, W., Lu, W., Zhang, H. & Li, X. Aqueous flow batteries: research and development. Chem. Eur. J. 25, 1649–1664 (2019).

Shigematsu, T. Redox flow battery for energy storage. Sei Tech. Rev. 73, 4–13 (2011).

Noack, J., Roznyatovskaya, N., Herr, T. & Fischer, P. The chemistry of redox-flow batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 9776–9809 (2015).

Wei, X. et al. Materials and systems for organic redox flow batteries: status and challenges. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 2187–2204 (2017).

Singh, V., Kim, S., Kang, J. & Byon, H. R. Aqueous organic redox flow batteries. Nano Res. 12, 1988–2001 (2019).

Winsberg, J., Hagemann, T., Janoschka, T., Hager, M. D. & Schubert, U. S. Redox-flow batteries: from metals to organic redox-active materials. Ang. Chem. Int. Ed. Eng. 56, 686–711 (2017).

Winsberg, J. et al. TEMPO/Phenazine combi-molecule: a redox-active material for symmetric aqueous redox-flow batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 1, 976–980 (2016).

Huang, C.-Y. et al. N,N′-disubstituted indigos as readily available red-light photoswitches with tunable thermal half-lives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 15205–15211 (2017).

Lin, K. et al. Alkaline quinone flow battery. Science 349, 1529–1532 (2015).

Wang, W. et al. Recent progress in redox flow battery research and development. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 970–986 (2013).

Chen, R. Redox flow batteries for energy storage: recent advances in using organic active materials. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 21, 40–45 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. A sustainable redox flow battery with alizarin-based aqueous organic electrolyte. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2, 2469–2474 (2019).

Hoober-Burkhardt, L. et al. A new Michael-reaction-resistant benzoquinone for aqueous organic redox flow batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, A600–A607 (2017).

Lv, Y. et al. Structure reorganization-controlled electron transfer of bipyridine derivatives as organic redox couples. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 27016–27022 (2019).

Luo, J. et al. Unprecedented capacity and stability of ammonium ferrocyanide catholyte in pH neutral aqueous redox flow batteries. Joule 3, 149–163 (2019).

Hu, B., DeBruler, C., Rhodes, Z. & Liu, T. L. Long-cycling aqueous organic redox flow battery (AORFB) toward sustainable and safe energy storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1207–1214 (2017).

DeBruler, C. et al. Designer two-electron storage viologen anolyte materials for neutral aqueous organic redox flow batteries. Chemistry 3, 961–978 (2017).

Hofmann, J. D. & Schröder, D. Which parameter is governing for aqueous redox flow batteries with organic active material? Chem. Ing. Tech. 91, 786–794 (2019).

Hollas, A. et al. A biomimetic high-capacity phenazine-based anolyte for aqueous organic redox flow batteries. Nat. Energy 3, 508–514 (2018).

Lee, W., Permatasari, A., Kwon, B. W. & Kwon, Y. Performance evaluation of aqueous organic redox flow battery using anthraquinone-2,7-disulfonic acid disodium salt and potassium iodide redox couple. Chem. Eng. J. 358, 1438–1445 (2019).

Lee, W., Permatasari, A. & Kwon, Y. Neutral pH aqueous redox flow batteries using an anthraquinone-ferrocyanide redox couple. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 5727–5731 (2020).

Permatasari, A., Lee, W. & Kwon, Y. Performance improvement by novel activation process effect of aqueous organic redox flow battery using tiron and anthraquinone-2,7-disulfonic acid redox couple. Chem. Eng. J. 383, 123085 (2020).

Gerken, J. B. et al. Comparison of quinone-based catholytes for aqueous redox flow batteries and demonstration of long-term stability with tetrasubstituted quinones. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2000340 (2020).

Hu, B., Luo, J., Hu, M., Yuan, B. & Liu, T. L. A pH-neutral, metal-free aqueous organic redox flow battery employing an ammonium anthraquinone anolyte. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 16629–16636 (2019).

Beh, E. S. et al. A neutral pH aqueous organic–organometallic redox flow battery with extremely high capacity retention. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 639–644 (2017).

Luo, J., Hu, B., Hu, M., Zhao, Y. & Liu, T. L. Status and prospects of organic redox flow batteries toward sustainable energy storage. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 2220–2240 (2019).

Liu, T., Wei, X., Nie, Z., Sprenkle, V. & Wang, W. A total organic aqueous redox flow battery employing a low cost and sustainable methyl viologen anolyte and 4-HO-TEMPO catholyte. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1501449 (2016).

Kaur, R., Manjal, S. K., Rawal, R. K. & Kumar, K. Recent synthetic and medicinal perspectives of tryptanthrin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 25, 4533–4552 (2017).

Deryabin, P. I., Moskovkina, T. V., Shevchenko, L. S. & Kalinovskii, A. I. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of tryptanthrin adducts with ketones. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 53, 418–422 (2017).

Novak, M. J., Clayton Baum, J., Buhrow, J. W. & Olson, J. A. Scanning tunneling microscopy of indolo[2,1-b]quinazolin-6,12-dione (tryptanthrin) on HOPG: evidence of adsorption-induced stereoisomerization. Surf. Sci. 600, L269–L273 (2006).

Bhattacharjee, A. K. et al. Analysis of stereoelectronic properties, mechanism of action and pharmacophore of synthetic indolo[2,1-b]quinazoline-6,12-dione derivatives in relation to antileishmanial activity using quantum chemical, cyclic voltammetry and 3-D-QSAR CATALYST procedures. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 10, 1979–1989 (2002).

Kawakami, J. et al. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of tryptanthrin derivatives. Trans. Mater. Res. Soc. Jpn. 36, 603–606 (2011).

Filatov, A. S. et al. Concise synthesis of tryptanthrin spiro analogues with in vitro antitumor activity based on one-pot, three-component 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of azomethine ylides to сyclopropenes. Synthesis 51, 713–729 (2019).

Amara, R. et al. Conversion of isatins to tryptanthrins, heterocycles endowed with a myriad of bioactivities. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 5302–5312 (2019).

Klimovich, A. A., Popov, A. M., Krivoshapko, O. N., Shtoda, Y. P. & Tsybulsky, A. V. A comparative assessment of the effects of alkaloid tryptanthrin, rosmarinic acid, and doxorubicin on the redox status of tumor and immune cells. Biophysics 62, 588–594 (2017).

Jahng, Y. Progress in the studies on tryptanthrin, an alkaloid of history. Arch. Pharm. Res. 36, 517–535 (2013).

Pinheiro, D. et al. Tryptanthrin from indigo: synthesis, excited state deactivation routes and efficient singlet oxygen sensitization. Dyes Pigments 175, 108125 (2020).

Seixas de Melo, J. S. In Photochemistry. Vol. 47 (eds A. Albini & S. Prodi) 196–216 (RSC, 2020).

Pina, J. et al. Excited-State Proton Transfer in Indigo. J. Phys. Chem. B 121, 2308–2318 (2017).

Seixas de Melo, J. S., Serpa, C., Burrows, H. D. & Arnaut, L. G. The triplet state of indigo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 2094–2096 (2007).

Kogawa, C. et al. Synthesis and photophysical properties of azuleno[1′,2′:4,5]pyrrolo[2,1-b]quinazoline-6,14-diones: azulene analogs of tryptanthrin. Tetrahedron 74, 7018–7029 (2018).

Liang, J. L., Park, S.-E., Kwon, Y. & Jahng, Y. Synthesis of benzo-annulated tryptanthrins and their biological properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20, 4962–4967 (2012).

Pereira, R. C., Pineiro, M., Galvão, A. M. & Seixas de Melo, J. S. Thioindigo, and sulfonated thioindigo derivatives as solvent polarity dependent fluorescent on-off systems. Dyes Pigments 158, 259–266 (2018).

Tucker, A. M. & Grundt, P. The chemistry of tryptanthrin and its derivatives. ARKIVOC, 546–569 (2012).

Chen, H., Cong, G. & Lu, Y.-C. Recent progress in organic redox flow batteries: active materials, electrolytes and membranes. J. Energy Chem. 27, 1304–1325 (2018).

Hu, B., Seefeldt, C., DeBruler, C. & Liu, T. L. Boosting the energy efficiency and power performance of neutral aqueous organic redox flow batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 22137–22145 (2017).

Lin, K. et al. A redox-flow battery with an alloxazine-based organic electrolyte. Nat. Energy 1, 16102 (2016).

Senthilkumar, S. T. et al. Energy efficient Na-aqueous-catholyte redox flow battery. Energy Storage Mater. 12, 324–330 (2018).

Luo, J. et al. Unraveling pH dependent cycling stability of ferricyanide/ferrocyanide in redox flow batteries. Nano Energy 42, 215–221 (2017).

Lai, Y. Y. et al. Stable low-cost organic dye anolyte for aqueous organic redox flow battery. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 2290–2295 (2020).

Rubio-Garcia, J., Kucernak, A., Parra-Puerto, A., Liu, R. & Chakrabarti, B. Hydrogen/functionalized benzoquinone for a high-performance regenerative fuel cell as a potential large-scale energy storage platform. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 3933–3941 (2020).

Elgrishi, N. et al. A practical beginner’s guide to cyclic voltammetry. J. Chem. Educ. 95, 197–206 (2018).

Nicholson, R. S. Theory and application of cyclic voltammetry for measurement of electrode reaction kinetics. Anal. Chem. 37, 1351–1355 (1965).

Yao, Y., Lei, J., Shi, Y., Ai, F. & Lu, Y.-C. Assessment methods and performance metrics for redox flow batteries. Nat. Energy https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-00772-8 (2021).

Monteiro, R., Leirós, J., Boaventura, M. & Mendes, A. Insights into all-vanadium redox flow battery: a case study on components and operational conditions. Electrochim. Acta 267, 80–93 (2018).

Yang, B. et al. High-performance aqueous organic flow battery with quinone-based redox couples at both electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 163, A1442–A1449 (2016).

Sánchez-Díez, E. et al. Redox flow batteries: status and perspective towards sustainable stationary energy storage. J. Power Sources 481, 228804 (2021).

Brandão, P., Pinheiro, D., Seixas de Melo, J. S. & Pineiro, M. I2/NaH/DMF as oxidant trio for the synthesis of tryptanthrin from indigo or isatin. Dyes Pigments 173, 107935 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Projects “Hylight” (No. 031625) 02/SAICT/2017, PTDC/QUI-QFI/31625/2017, which is funded by the Portuguese Science Foundation (FCT) and Compete Centro 2020 and project “SunStorage - Harvesting and storage of solar energy”, reference POCI-01-0145-FEDER-016387, funded by European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), through COMPETE 2020—Operational Program for Competitiveness and Internationalization (OPCI), and by national funds, through FCT. The Coimbra Chemistry Center is supported by FCT, through Projects UIDB/00313/2020, and UIDP/00313/2020. FCT is also gratefully acknowledged for a Ph.D. grant to D.P. (ref SFRH/BD/74351/2010). D.P. also acknowledges project “SunStorage—Harvesting and storage of solar energy” for a research grant. We also acknowledge the UC-NMR facility for obtaining the NMR data (www.nmrccc.uc.pt).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S.S.M. formulated the project. D.P. synthesized, with the help of M.P., in the synthetic strategy, the compound and collected the HPLC-DAD data. D.P. and M.P. analyzed the NMR, HPLC-DAD, and Infrared data. D.P. measured the solubility, collected, and analyzed the electrochemical data, and performed the RFBs cell tests. J.S.S.M. wrote the article with the contribution of D.P. and M.P. All authors contributed to the overall scientific interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A patent request deposit no. 20201000045444 (IPN) was made on 11 September 2020 with the contribution of all authors.

Additional information

Peer review information Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pinheiro, D., Pineiro, M. & de Melo, J.S.S. Sulfonated tryptanthrin anolyte increases performance in pH neutral aqueous redox flow batteries. Commun Chem 4, 89 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-021-00523-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-021-00523-0

This article is cited by

-

Tryptanthrin derivatives as efficient singlet oxygen sensitizers

Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.