Abstract

Ketones are widely applied moieties in designing functional materials and are commonly obtained by oxidation of alcohols. However, when alcohols are protected/functionalized, the direct oxidation strategies are substantially curbed. Here we show a highly efficient copper bromide promoted one-step direct oxidation of benzylic ethers to ketones with the aid of a fullerene pendant. Mechanistic studies unveil that fullerene can serve as an electron pool proceeding the one-step oxidation of alkoxy group to ketone. In the absence of the fullerene pendant, the unreachable activation energy threshold hampers the direct oxidation of the alkoxy group. In the presence of the fullerene pendant, generated fullerene radical cation can activate the neighbour C–H bond of the alkoxy moiety, allowing a favourable energy barrier for initiating the direct oxidation. The produced fullerene-fused ketone possesses high thermal stability, affording the pin-hole free and amorphous electron-transport layer with a high electron-transport mobility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

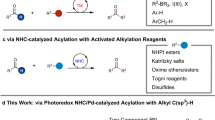

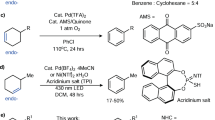

Oxidation reactions, such as the direct oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes or ketones, are among the most critical and fundamental transformations in organic synthesis1. However, the oxidation methods are limited when alcohols are protected/functionalized with an alkyl group to form the alkoxy structure2, which is mainly attributed to high activation energy barrier for directly converting the alkoxy group to ketone structure3. Consequently, the one-step direct oxidation of alkoxy to ketone has yet to be presented. Fullerene, a well-known intrinsically electron-deficient molecule, is prone to accept electrons affording the reduced fullerene anion species for versatile functionalizations4,5. With our interest in exploring the classical organic chemistry reaction under assistance of fullerene, and also inspired by the recent studies on fullerene radical cation (C60•+)-mediated reaction6,7, we conceived that C60•+ should be feasible for the one-step oxidation of alkoxy group to ketone through the electron transfer activation.

Herein, we report that a copper (II) bromide promoted one-step direct oxidation of alkoxy to ketones with the aid of an oxidizable fullerene pendant (Fig. 1). Distinct from the unfavourable energy barrier in direct oxidation of alkoxy group to ketone, fullerene pendant serves as an electron pool for facilitating the electron transfer from the alkoxy structure to oxidant. Mechanistic studies indicate that the fullerene-assisted one-step oxidation involves two critical steps: (1) electron transfer from C60 to Cu[II] affords C60•+, and (2) the generated C60•+ attracts electron density from the neighbouring C–H bond, contributing to the further electron transfer from the alkoxy structure to the fullerene cage. Meanwhile, the obtained fullerene-fused ketones are fabricated to the electron-transport layers through thermally deposition, which provides the photovoltaic devices with uniformly pin-hole-free electron-transport films. The reaction presented herein not only provides an understanding on one-step oxidation of alkoxy group to ketone, but also access the high-quality electron-transport layers through thermally evaporation.

Results and discussion

Reaction optimization

Applied alkoxy substrate, indano[60]fullerene 1a, was synthesized according to our previously reported fullerene-cation-mediated synthetic strategy8. The optimized reactions are summarized in Table 1, which includes the screening of the oxidants, reaction temperature and reaction time. The optimized conditions successfully achieved [60]fullerene-fused ketone 2a, which was obtained in an isolated yield of 94%, with 4.0 equiv. CuBr2 as oxidant in an ortho-dichlorobenzene (o-DCB) solution at 100 °C for 1.5 h under an argon atmosphere (entry 12). It is worth noting that 2a can be obtained in equally high yield when the reaction was carried out in ambient environment (entry 14). Thus, this reaction appears to have high efficiency and ease of operation, which would be useful for industrial-scale synthesis of fullerene-fused ketones.

Substrate scope of the one-step oxidation reaction

The substrate scope was further explored with some representative compounds. As shown in Table 2, this one-step oxidation reaction proceeded smoothly to afford 2a–d in excellent yields. The optimized condition produced ketone 2a with an isolated yield of 94% (entry 1). Methyl-substituted ketone 2b was obtained in a similarly high yield of 93% (entry 2). To investigate the electronic effect of substituents, electron-withdrawing 4-fluoro- and electron-donating 4-methoxy-functionalized indano[60]fullerene substrates were synthesized. The corresponding ketones 2c and 2d were successfully isolated in excellent yields of 92% and 94%, respectively (entries 3 and 4) (for NMR spectra see Supplementary Figs. 14–26).

Isotope-labelling experiments for determining the oxygen source

Efficient oxidation of alkoxy indano[60]fullerene 1a proceeded even under the argon atmosphere, indicating that the oxygen source was not directly from the air. Then, the oxygen source for this one-step oxidation was determined by performing the reaction in the presence of 18O isotope-labelled water (H218O) within a sealed tube (Fig. 2). The control experiment was performed without the addition of H218O under the optimized conditions. Then, the molecular weight of the product 2a was measured by high-resolution mass spectrum (HRMS), which showed a mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of 824.0260 corresponding to non-18O-labelled 2a (Fig. 2a). When the reaction was carried out in the presence of H218O, a peak at m/z 826.0342 was clearly observed by HRMS, indicating that the obtained ketone contained 18O in its carbonyl group (Fig. 2b). Therefore, the oxygen source for this oxidation reaction is H2O rather than the methoxy group or O2 from the air. Notably, although an excess of H218O was used, the mass peak of non-18O-labelled ketone 2a can still be seen in the HRMS spectrum of the 18O-labelled ketone 2a-(18O) (see Supplementary Figs. 1, 27, 28 and Supplementary Tables 1, 2 for details).

Kinetic studies

Reaction kinetics of this one-step direct oxidation reaction were measured to further understand the reaction characteristics (Fig. 3). All reactions were performed under the same conditions except varying the temperature. The concentration changes over time were monitored by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (see Supplementary Figs. 2–5 and Supplementary Tables 3–6 for details). The change in concentration of reactant 1a and product 2a over time clearly indicated that this oxidation reaction reached equilibrium faster and gave higher yield when the reaction temperature increased (Fig. 3a, b). No by-products were formed during the transformation of 1a–2a, demonstrating that this oxidation route has high selectivity and efficiency. The consumption ratio of 1a was plotted on a logarithmic scale to determine the reaction order. The natural logarithm of the 1a consumption ratio exhibited a strong linear time dependence, suggesting that this oxidation reaction exhibit the first-order characteristics (Fig. 3c). The rate constant (k) dramatically increased from 6.4 × 10−4 mol−1 L−1 s−1 to 7.8 × 10−3 mol−1 L−1 s−1 when the reaction temperature was increased from 353 to 375 K (Table 3). Next, the activation energy Ea, activation enthalpy ΔH‡, activation entropy ΔS‡, and activation Gibbs free energy ΔG‡ were obtained from Arrhenius plots (ln k vs. 1/T) and Eyring plots (ln(k/T) vs. 1/T) on the basis of following equations, respectively (Fig. 3d)9,10:

Here, k is the rate constant, T is the temperature, R is the gas constant, ln A is a constant, kB is the Boltzmann constant and h is the Planck constant. The results summarized in Table 1 indicate that this one-step direct oxidation has an Ea of 120.6 kJ mol−1, with an endothermic ΔH‡ of 116.4 kJ mol−1, a positive ΔS‡ of 6.2 J mol−1 K−1.

Reaction conditions: 1a (3.0 mg, 3.6 μmol), CuBr2 (4.0 equiv.), o-DCB (3.0 mL). a Concentration of 1a over time at different temperatures. b Concentration of 2a over time at different temperatures. c Plots of ln([1a]0/[1a]) over time at different temperatures, where [1a]0 and [1a] are the initial and remaining concentrations of 1a, respectively. d Arrhenius plot (black) and Eyring plot (blue) for this one-step oxidation reaction.

Mechanistic studies

To gain more understandings on this one-step oxidation reaction, further investigations were carried out to understand the additional products and active intermediates. In situ proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) was applied to analyse in which form of the methyl group in 1a exists the reaction (Fig. 4a). As shown in Fig. 4a, 1H NMR of 1a clearly depicted a methyl peak with a chemical shift (δ) at 4.252 ppm. After the reaction was fished, the in situ 1H NMR of reaction mixture indicated a disappearance of methyl peak in 1a, while a new singlet peak appeared at δ = 2.619 ppm. Compared to the methyl peak in methanol (δ = 2.827), which we hypothesized as the potential leaved form of the methyl in this reaction, the reaction mixture showed substantially up-field shifted. In addition, the reaction mixture was found to be acidic, indicating the generation of acid during the reaction. Accordingly, we hypothesized that the 1H NMR signal (δ = 2.619) of the reaction mixture should be derived from the methyl in CH3Br11, which was produced by the reaction between the generated HBr and MeOH leaving from 1a especially reacting at high temperature. Meanwhile, when CH3Br was formed, H2O was simultaneously generated, which could then serve again as an oxygen source for this oxidation. Also, this result explained why non-18O-labelled 2a was still detected even when we used a large excess of H218O. Therefore, the methyl group in 1a left in a methanol form, which further suggests that this oxidation reaction should involve a hemiketal intermediate. Moreover, the 1H NMR peaks depicted at the typical aromatic region indicates the obvious down-field shift of 2a compared to 1a, which is attributed to the electron deficiency of carbonyl group in 2a (see Supplementary Fig. 6 for details). Also, the slightly positive ΔS‡ of this reaction reasonably explained the increased disorder because of the additional products of MeOH and HBr. Besides the analysis of additional products that are generated during the reaction, further experiments were performed to confirm which active intermediate that mediated this one-step oxidation. The radical scavenger 2,2,6,6-tertramethyl-1-piperidinyloxyl (TEMPO) was applied to confirm the generation of C60•+ intermediate from the single-electron transfer between fullerene and CuBr2 (Fig. 4b). When the reaction was run in the presence of 4.0 equiv. of TEMPO, the yield of 2a was dramatically decreased from 95 to 8%. A further increase in amount of TEMPO to 10.0 equiv. stopped the reaction, suggesting that the electron transfer process was completely suppressed. Therefore, the one-step direct oxidation of the alkoxy is initiated by electron transfer from C60 to CuBr2, and C60•+ plays a key role in the following oxidation steps.

Our mechanistic insights regarding the C60•+ intermediate mediated one-step oxidation are provided in Fig. 5. Based on the above experimental results and our previous research7, we considered that the oxidation of fullerene to C60•+ through single-electron transfer in the presence of copper bromide demonstrate a critical role in this reaction. As depicted in Fig. 5, in this one-step oxidation, we hypothesized that the fullerene pendant in 1a is initially oxidized by CuBr2 via single-electron transfer, producing the key active specie, indano[60]fullerenyl radical cation I. Owing to the electron deficiency of C60•+, the neighbouring C–H bond is then cleaved to generate neutral radical II with the release of one proton, which then spontaneously reacts with the isolated bromide anion to form HBr. Next, CuBr2 further oxidizes II to generate corresponding cation III, which undergoes nucleophilic addition by H2O, producing hemiketal intermediate IV. Finally, [60]fullerene-fused ketone 2a is produced through the loss of methanol and deprotonation. Meanwhile, the methanol produced can react with HBr to generate CH3Br and H2O, which then quickly reacts with benzyl cation III (see Supplementary Fig. 7 for details). Therefore, fullerene pendant can facilitate the one-step direct oxidation of the alkoxy group to ketone by serving as an electron pool.

Computational studies

To provide further support for the proposed mechanism, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to understand the key species and reaction barriers (Fig. 6, see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Table 7 for details). The DFT results indicated that the rate-determining step is proton transfer from H2O to the methoxy group, which had computed potential energy barrier of 124.5 kJ mol−1, in good agreement with the experiment value. It should be noted that Br– efficiently accelerated this proton transfer, as shown by DFT calculations in the absence of Br– (see Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 9 for details). In addition, the calculations showed facile oxidation of 1a by copper (II) and relatively easy deprotonation of I to form the benzyl cation III and HBr, with an energy barrier on the order of 38.6 kJ mol−1 (see Supplementary Fig. 9 for details). Therefore, CuBr2 plays two roles in this one-step oxidation reaction: (a) oxidation of fullerene via electron transfer with assistance of bromide anion, (b) proton transfer for formation of the hemiketal through the formation of Br–.

Performance of evaporable fullerene-fused ketone

So far, fullerene derivatives have been demonstrated as versatile and high-performance n-type semiconductive materials in both organic solar cells and recently boosted perovskite solar cells12,13,14, but the high-performance fullerene derivatives electron-transport materials have never been achieved using vacuum-deposition process15,16,17. Accordingly, both the indano[60]fullerene 1a and the produced fullerene-fused ketone 2a were further processed through the vacuum-deposition process to fabricate the electron-transport layer. HPLC analysis of vacuum-deposited 1a-film indicated that 1a is instable in the vacuum-deposition process, which affords a mixture of thermally decomposed compounds (Fig. 7a). Meanwhile, thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) showed that 1a has an initial decomposing temperature at 258.9 °C with a 18.3% weight loss (see Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10 for details). Consistent with the HPLC analysis of vacuum-deposited 1a-film, such dramatically high weight-loss ratio of 1a can be attributed to a mixture of decomposed compounds. We observed that no thermally decomposed components were detected when vacuum-depositing 2a, which indicated that the fullerene-fused ketone has a better stability (Fig. 7b). Further TGA manifested that 2a show high thermal stability with an initial decomposing temperature at 409.5 °C, which is much thermally stable than that of 1a or PC61BM (see Supplementary Fig. 11 for details). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was carried to compare the morphology of spin-coated and vacuum-deposited 2a-films, respectively. Figure 7c indicated that the spin-coated 2a-film show obvious pinholes with substantial crystalline found in the selected area electron diffraction (see Supplementary Fig. 12a for details). In stark contrast, the vacuum-deposited 2a-film exhibits a highly uniform and amorphous morphology, which benefits the high electron-transport performance (Fig. 7d and See Supplementary Fig. 12b for details)15,18. To evaluate the charge carrier mobility of fullerene-fused ketone 2a, space-charge-limited current (SCLC) measurements were applied to compare the trap-filling limit voltage (VTFL) and trap density (nt) of spin-coated and vacuum-deposited 2a-films, respectively (Fig. 7e, f). In well accordance with TEM observations, the spin-coated 2a-film showed more defects with higher VTFL (1.49 V) and nt (1.4 × 1018 cm−3), compared with VTFL (1.01 V) and nt (9.3 × 1017 cm−3) of the vacuum-deposited 2a-film. Moreover, additional SCLC measurements further compared vacuum-deposited C60- and 2a-films (Fig. 7g, h). The 2a film exhibited an equally high electron mobility (2.16 × 10−6 cm2 V−1 s−1) compared with C60 film (2.33 × 10−6 cm2 V−1 s−1), which suggests that fullerene-fused ketone can be applied as an efficient electron-transport layer to replace the pristine [60]fullerene in perovskite solar cells. Besides the electron-transport mobility comparison of 2a, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy level of 2a is also evaluated through cyclic voltammetry (see Supplementary Tables 9 and 10 for details). Compared with LUMO levels of alkoxy substrates 1, fullerene-fused ketones 2 show ~0.1 eV lower LUMO levels due to the electron-withdrawing property of carbonyl group. It should be noted that fullerene-fused ketones indicate the lowest LUMO energy levels among fullerene derivatives by far, which doubtlessly are compatible with common perovskite materials such as CH3NH3PbI3. Meanwhile, DFT calculations demonstrate that fullerene-fused ketones have a deep enough highest occupied molecular orbital energy level, which is capable of blocking holes from recombining with electrons in photovoltaics (see Supplementary Table 11 for details). In addition, the UV–vis spectra were applied to compare the visible light absorption of vacuum-deposition fabricated 2a-film and C60 film (see Supplementary Fig. 13 for details). The absorption spectrum of 2a showed an obvious blue-shift compared to that of C60 at two typical fullerene absorption positions around 250 and 330 nm, which was further confirmed through DFT computation. This significant blue-shift is contributed by the strong electron-withdrawing carbonyl group in 2a. More interestingly, compared to C60, 2a shows a much weak light absorption at a range of 400–650 nm, where is a typical absorption range for perovskite materials, providing a better light absorption for the perovskite materials when using 2a as the electron-transporting layer in a normal-type structure.

HPLC analyses of a Vacuum-deposited indano[60]fullerene 1a-film. b Vacuum-deposited [60]fullerene-fused ketone 2a-film. TEM observations of c Spin-coated 2a-film and d Vacuum-deposited 2a-film with the magnification as an inset. Trap density measurement of e Spin-coated 2a-film and f vacuum-deposited 2a-film. The SCLC based electron mobility measurement of g vacuum-deposited C60-film and h Vacuum-deposited 2a-film.

In summary, here we report a facile CuBr2-promoted one-step direct oxidation of alkoxy to ketone with the aid of an oxidizable fullerene pendant. The mechanistic investigation demonstrates in situ generated fullerenyl radical cation (C60•+) behaves as an electron pool to facilitate the one-step direct oxidation: (a) initiating oxidation via electron transfer from C60 to CuBr2 to form C60•+ and (b) activating cleavage of the neighbouring C–H bond by withdrawing electrons from the bond and subsequently affording the key hemiketal intermediate. Moreover, we found that produced fullerene-fused ketone can form the high-quality electron-transport film using the vacuum-deposited process. Therefore, this reaction will not only provide a useful method in fundamental organic chemistry regarding the direct oxidation of alkoxy to ketone and in fullerene cation chemistry, but also provide an evaporable fullerene material for high-performance electron-transport material in perovskite solar cells.

Methods

General procedures for the one-step oxidation reaction

For fullerene-fused ketones 2, all reactions were performed by using 0.03 mmol of 1, 0.12 mmol anhydrous CuBr2 (Sigma-Aldric) in 10.0 mL of anhydrous o-DCB under an argon atmosphere or open-air condition at 100 °C for 1.5 h. After reaction was over, resulting mixture was directly filtered through a silica gel plug to remove insoluble salt, and then evaporated in vacuo to remove the excess solvent. Finally, the residue was further separated on a silica gel column with CS2 or CS2/dichloromethane as eluents to afford products 2 (see Supplementary Methods for details).

18O isotope-labelled experimental procedure

3.0 mg (3.6 μmol) of 1a and 1.5 μL of H218O (0.072 mmol, 20.0 equiv) were added to 3.0 mL of anhydrous o-DCB solution in the presence of CuBr2 (3.2 mg, 14.4 μmol, 4.0 equiv). After being vigorously stirred at 100 °C for 1.5 h with a tiny sealed tube, resulting mixture was directly filtered through a silica gel plug to remove insoluble materials. Finally, the filitrate was condensed in vacuo for the following HRMS measurement.

TEMPO experimental procedure

3.0 mg (3.6 μmol) of 1a, 3.2 mg of CuBr2 (14.4 μmol, 4.0 equiv) and TEMPO (2.3 mg, 4.0 equiv; 5.6 mg, 10.0 equiv) were added to 3.0 mL of anhydrous o-DCB solution. After being vigorously stirred at 100 °C for 1.5 h under the argon atmosphere, resulting mixture was directly filtered through a silica gel plug to remove insoluble materials. Finally, ca. 50 μL of filitrate was directly loaded on HPLC to analyse results.

Measurement of trap-filling limit voltage (V TFL) and trap density (n t)

VTFL and nt were evaluated based on SCLC using charge carrier only devices with a configuration of ITO/fullerenes (75 nm)/Au (60 nm). The VTFL and nt were calculated from the following equation: \(V_{{\mathrm{TFL}}} = \frac{{n_ted^2}}{{2{\upvarepsilon}_0{\upvarepsilon}_r}}\), where e is electric charge (1.602 × 10−16 V m−1), ε0 is the vacuum permittivity (8.85 × 10−19 V m−1), εr is the relative permittivity taken as 46.9 and d is the thickness of the fullerene layer. The thickness of the fullerene layer was measured by using cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy. The experimental dark current density was measured under an applied voltage swept from 0 to −5 V.

Measurement of electron mobility

The electron-transport layer only device with a configuration of ITO/Fullerenes (30 nm)/Al (80 nm) was fabricated to evaluate the electron carrier mobility of synthesized fullerene-fused ketone. The mobility was determined by fitting the dark current to a model of a SCLC, which is described by the equation: \(J_{{\mathrm{SCLC}}} = \frac{{9{\upvarepsilon}_0{\upvarepsilon}_r\mu V^2}}{{8L^3}}\), where JSCLC is the current density, µ is the electron mobility, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity (8.85 × 10−19 V m−1), ε0 is the relative permittivity taken as 46.9, L is the thickness of the fullerene layer and V is the effective voltage. The thickness of the fullerene layer was measured by using cross-sectional SEM. The experimental dark current density was measured under an applied voltage swept from 0 to –3 V.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files, or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Carey, F. A. & Giuliano, R. M. Organic Chemistry, (McGraw-Hill Education, 2016).

Firouzabadi, H. & Pourali, A. R. Dinitrogen tetroxide-impregnated charcoal (N2O4/charcoal): selective nitrosation of amines, amide, ureas, and thiols. Syn. Comm. 35, 1527–1533 (2005).

Gilissen, P. J., Blanco-Ania, D. & Rutjes, F. P. J. T. Oxidation of secondary methyl ethers to ketones. J. Org. Chem. 82, 6671–6679 (2017).

Fagan, P. J., Calabrese, J. C. & Malone, B. The chemical nature of buckminsterfullerene (C60) and the characterization of a platinum derivative. Science 252, 1160–1161 (1991).

Echegoyen, L. & Echegoyen, L. E. Electrochemistry of fullerenes and their derivatives. Acc. Chem. Res. 31, 593–601 (1998).

Hashiguchi, M. et al. FeCl3-Mediated synthesis of fullerenyl esters as low-LUMO acceptors for organic photovoltaic devices. Org. Lett. 14, 3276–3279 (2012).

Lin, H.-S. & Matsuo, Y. Functionalization of [60]fullerene through fullerene cation intermediates. Chem. Comm. 54, 11244–11259 (2018).

Lin, H.-S. et al. Highly selective and scalable fullerene-cation-mediated synthesis accessing cyclo[60]fullerenes with five-membered carbon ring and their application to perovskite solar cells. Chem. Mater. 31, 8432–8439 (2019).

Arrhenius, S. A. Über die dissociationswärme und den einfluss der temperatur auf den dissociationsgrad der elektrolyte. Z. Phys. Chem. 4, 96–116 (1889).

Eyring, H. J. The activated complex in chemical reactions. J. Chem. Phys. 3, 107–115 (1935).

Lacey, M. J., Macdonald, C. G., Pross, A., Shannon, J. S. & Sternhell, S. Geminal interproton coupling constants in some methyl derivatives. Aust. J. Chem. 23, 1421–1429 (1970).

He, Y., Chen, H.-Y., Hou, J. & Li, Y. Indene-C60 bisadduct: a new acceptor for high-performance polymer solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1377–1382 (2010).

Li, Y. et al. Multifunctional fullerene derivative for interface engineering in perovskite solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 15540–15547 (2015).

Liu, K. et al. Fullerene derivative anchored SnO2 for high-performance perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 3463–3471 (2018).

Lin, H.-S. et al. Achieving high efficiency in solution-processed perovskite solar cells using C60/C70 mixed fullerenes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 39590–39598 (2018).

Collavini, S. et al. Efficient regular perovskite solar cells based on pristine [70]fullerene as electron-selective contact. ChemSusChem 9, 1263–1270 (2016).

Lee, K.-M. et al. Thickness effects of thermally evaporated C60 thin films on regular-type CH3NH3PbI3 based solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 164, 13–18 (2017).

Zhang, K. et al. Fullerenes and derivatives as electron transport materials in perovskite solar cells. Sci. China Chem. 60, 144–150 (2017).

Ueno, H. et al. Kinetic study of the diels–alder reaction of Li+@C60 with cyclohexadine: greatly increased reaction rate by encapsulated Li+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 11162–11167 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP18H05329, JP20H00220 and JP20J13124. Also, we would like to thank Strategic International Research Cooperative Program (SICORP, Grant Number JPMJSC18H1) and CREST (JPMJCR20B5), Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.-S.L. and Y. Ma. are contributed equally to this work. H.-S.L. and Y. Mat. conceived the idea, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. H.-S. L., Y. Ma. and I.J. conducted experiments, R.X. and S.M. conducted TEM observations. S.M. conducted DFT calculation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, HS., Ma, Y., Xiang, R. et al. One-step direct oxidation of fullerene-fused alkoxy ethers to ketones for evaporable fullerene derivatives. Commun Chem 4, 74 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-021-00511-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-021-00511-4

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.