Abstract

Spiro polycyclic compounds bearing pyran ring systems are found in bioactive molecules, and we recently reported the construction of spirooxindole all-carbon polycycles. Here we show the development of catalytic stereoselective annulation reactions that afford spirooxindole pyran polycycles. Oxindole-derived spiro[4,5]decanes are reacted with arylglyoxal to construct a pyran ring via the formation of carbon-carbon and carbon-oxygen bonds through dynamic aldol-oxa-cyclization cascade reactions, leading to the formation of spirooxindole pyran polycycles bearing six stereogenic centers as single diastereomers. During the reaction, the starting material is isomerized to the diastereomer, and this is key to afford the product. Taking advantage of this isomerization, highly enantiomerically enriched single diastereomers of spirooxindole pyran polycycles are obtained. The reactions generating the spiro pyran polycycles show stereoselectivities distinct from those previously observed in the construction of all-carbon polycycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

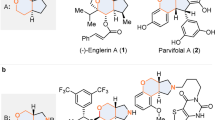

Pyran-derived polycycles bearing spiro ring systems and spirooxindole scaffolds are found in bioactive natural products and pharmaceutical agents1,2,3,4,5,6 (Fig. 1a). Whereas syntheses of many classes of spirooxindole polycycles bearing N-heterocycles and spirooxindole all-carbon polycycles have been reported7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, few examples of the syntheses of spirooxindole polycycles bearing O-heterocycles have been reported22,23. Most methods developed for the synthesis of the spirooxindole O-heterocycles provide nonpolycyclic derivatives24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Because the lengths of C–C, C–N, and C–O bonds are different, spirooxindole polycyclic scaffolds bearing oxygen-containing heterocycles should provide molecules with biological functions different from those of spirooxindole all-carbon polycyclic and N-heterocycle-containing polycyclic systems.

Development of reactions to afford spirooxindole pyran polycycles. a Bioactive pyran polycycles1,2,3,4,5. b Synthesis of spirooxindole all-carbon polycycles from spiro[4,5]decane derivatives21. c Synthesis of spirooxindole pyran polycycles from the same spiro[4,5]decane derivatives (this study). The dynamic aldol-oxa-cyclization cascade reactions (reactions with C=O, in c) that provide pyran polycycles described here show stereoselectivities distinct from those previously observed in the Michael–Henry cascade reactions (reactions with C=C, in b)

In addition, the construction of polycyclic molecules through the formation of C–C and C–O bonds would provide structures with unique regio- and diastereoselectivities compared to those accessed via the formation of C–C and C–N bonds. Thus, the development of strategies and methods that provide access to polycyclic scaffolds21,34,35,36,37 bearing O-heterocycles and spirooxindole cores is of interest in drug discovery efforts and related research.

Here, we report a route to functionalized spirooxindole pyran polycycles. We report stereoselective construction of pyran polycycles using annulation reactions via the formation of C–C and C–O bonds; these reactions provide products with stereoselectivities distinct from those demonstrated in the formation of all-carbon polycycles (Fig. 1b, c).

Results

Design

Our strategy for the construction of spirooxindole pyran polycycles uses oxindole-derived spiro[4,5]decanes21 as starting materials (Fig. 1c). We have recently reported the construction of spirooxindole all-carbon polycyclic systems from one of the diastereomers of the spiro[4,5]decanes by the reactions with nitrostyrenes21 (Fig. 1b). Here, we used the same starting molecules, spiro[4,5]decanes and their diastereomers, and reacted these with arylglyoxals through aldol-oxa-cyclization cascade reactions to construct a pyran ring, leading to the formation of the spirooxindole pyran polycycles. We hypothesized that the actual reacting diastereomers of the spiro[4,5]decanes and the bond-forming positions would depend on reaction partners and the type of the bond formed (i.e., C–C or C–O). We also hypothesized that stereoselective formation of products would be achieved by selecting suitable catalysts and conditions including those that are involved in isomerization and equilibration of the reactants and the intermediates36,38,39,40.

Conditions for the formation of the spirooxindole pyran polycycles

First, catalysts and conditions were evaluated to identify those that catalyzed the reactions of oxindole-derived spiro[4,5]decane 1a or its diastereomer 2a with phenylglyoxal to afford pyran-derived polycycles (Table 1). Using DABCO as catalyst at room temperature (rt, 25 °C) in CH2Cl2, spirooxindole pyran polycycle 3a was formed from 2a (Table 1, entry 2). However, under the same conditions with 1a instead of 2a, formation of 3a was not detected (Table 1, entry 1). The use of DBU instead of DABCO under otherwise the same conditions led to the formation of 3a from 1a (Table 1, entry 3). With the use of DBU as catalyst under appropriate conditions, product 3a was obtained from both the reactions of 1a and of 2a (Table 1, entries 4 and 5). Relative stereochemistry of 3a was determined by X-ray crystal structural analysis, and the result indicated that 3a was derived from 2a (i.e., 3a retained the stereochemistries of the stereogenic centers in the cyclopentane ring of 2a). No formation of other diastereomers and of other products was observed under the conditions listed in Table 1. These results suggested that, with 1a as starting material, 1a first isomerized to 2a, and 2a reacted with phenylglyoxal to give 3a. When the reaction was performed in the presence of DBU (0.2 equiv) as catalyst with addition of H2O as an additive in CHCl3 at 0 °C, 3a was obtained in high yields (Table 1, entries 6 and 7). Note that in our previously reported synthesis of spirooxindole all-carbon polycycles, only 1a reacted with nitrostyrenes to afford the product21. The reactions with phenylglyoxal (in which the reactions are with the C=O group) showed distinct stereoselectivities from those previously observed in the construction of the all-carbon cyclohexane ring.

Isomerization of the starting material

Because the isomerization from 1a to 2a was essential to afford 3a from 1a, conditions for the isomerization were evaluated (Table 2). Pyridine did not isomerize 1a (Table 2, entry 1). Et3N and DABCO isomerized 1a to 2a, respectively, but the formation of 2a was slow (Table 2, entries 2 and 3). DBU efficiently isomerized 1a to 2a. During the isomerization of 1a, only the formation of 2a was observed; no isomers other than 1a and 2a were detected. Under the same DBU catalysis conditions, 2a was also isomerized to 1a and the ratio between 1a and 2a was the same as observed in the isomerization of 1a (Table 2, entries 8 and 9). These results indicate that the isomerization reactions between 1a and 2a reached the equilibrium in the presence of DBU regardless of whether the starting material was 1a or 2a. The isomerization between 1a and 2a occurred even in the presence of only 0.001 equiv (or 0.1 mol%) loading of DBU (Table 2, entries 8 and 9). To understand the mechanisms of the isomerization of 1a to 2a, deuteration experiments were performed under the DBU-catalyzed isomerization conditions (Table 3). To generate 2a from 1a, both the stereochemistries at position A (the α-position of the oxindole amide group) and at position B (the α-position of the ketone carbonyl group of the 5-membered ring) of 1a must be altered. Whereas the proton at position A of 1a was exchanged with deuterium, the proton at position B of 1a was not. In the formed 2a, similarly, position A was deuterated and position B retained H. These results suggest that the isomerization occurs through the enolization of the cyclohexane-1,3-dione moiety with the C–C bond cleaving and forming (Fig. 2). The isomerization and the deuteration results suggest that when compound 1a is enantiomerically enriched, the enantiomeric ratio (er) of 1a is retained in 2a; the stereochemistry of the β-position of the ketone carbonyl group of the cyclopentane ring is not affected by the isomerization. In fact, when enantiomerically enriched 1a (er 99.8:0.2) was treated with DBU, 2a was obtained in essentially the same er (er 99.7:0.3).

Scope of the annulation reaction

With the use of enantiomerically enriched 1 as the starting material in the reactions with arylgryoxals, under the conditions optimized for the formation of 3a from 1a, various enantiomerically enriched functionalized spirooxindole pyran polycycles 3 were obtained in one pot (Fig. 3). In all the cases, products 3 were isolated as single diastereomers in high yields with high enantiomeric ratios (up to er > 99.9:0.1). Whereas isomerization of 1a to 2a occurred in the presence of only 0.001 equiv of DBU as described above, the use of 0.2 equiv of DBU provided better results than the use of low loadings of DBU for the formation of 3. Hydrated arylglyoxal may act as weak acid to neutralize DBU, resulting in the requirement of the conditions containing 0.2 equiv of DBU for the efficient formation of 3. The utility of the reactions to form 3 was further demonstrated by the transformations of 3a to various polycyclic derivatives 4–8 (Fig. 4). Reduction of 3a using H2 and Pd/C afforded 4, in which the ring system was reorganized to provide a new spirooxindole pyran polycycle system. On the other hand, reduction of 3a using NaBH(OAc)3 afforded alcohol 6 without affecting the spiropolycyclic framework. Complex polycycles 7 and halogenated polycyclic products 5 and 8 were also obtained concisely.

Transformations of 3a. Full details are provided in the Supplementary Methods

Plausible pathway of the reaction

Based on the stereochemistry of product 3a, the reaction pathway for the formation of 3a from 1a is suggested as follows: when the cyclopentanone moiety of 1a had the (S,S) configuration, the si -face of the α-position of the oxindole amide group of 2a reacted with the re-face of the aldehyde group of phenylglyoxal during the C–C bond formation (Fig. 5). Then, the oxygen atom that originated from the aldehyde group reacted with the si-face of a specific ketone carbonyl group to afford 3a (Fig. 5a). In the reaction of a single enantiomer of 1a or 2a with phenylglyoxal, the number of possible product stereoisomers that may form is 48, calculated from 2 (selection of 1a or 2a) ×2 (reaction face selectivity of 1a or 2a) × 2 (reaction face selectivity of phenylglyoxal) × 6 (ketone positions and reaction faces of the ketones). During the reaction, formation of product diastereomers other than 3a and accumulation of intermediates (products of aldol reaction without C–O bond formation) were not detected. These results suggest that reversible processes are involved in the isomerization between 1a and 2a and in the aldol reaction C–C bond formation. The results also suggest that the kinetic control in the aldol reaction step is key for the selective formation of 3a. That is, the aldol C–C bond formation of either 1a or 2a with phenylglyoxal may occur without reaction face selectivities, but the aldol adducts that do not lead to the C–O bond formation may be quickly decomposed to the starting materials. The kinetically favoured transition state for the C–C bond formation would determine the reacting ketone group and its face used for the C–O bond formation in the cascade sequence, although the details of the reaction mechanisms will need to be studied further. In the previously reported reaction of 1a with nitrostyrene21, when the cyclopentanone moiety of 1a had the (S,S) configuration, it is deduced that the re-face of 1a reacted for the C–C bond formation (Fig. 5b) based on the stereochemistry of the product. It is also deduced that the α-position of the nitro group then reacted with the si-face of the specific ketone carbonyl group for the selective formation of product 921. Product 9 had a trans–cis relationship for the generated 5–6–6 ring system. In contrast, in the formation of 3a, the actual reactant was 2a, and the formed 5–6–6 ring system had a cis–cis relationship. The annulation via the aldol-oxa-cyclization of 1a with arylglyoxal showed completely different stereoselectivities from the annulation via the Michael–Henry reaction of 1a with nitrostyrene.

Pathways of the reaction a. a A plausible pathway for the formation of 3a from 1a. b A plausible pathway for the formation of 9 from 1a (the formation of 9 was described in ref. 21)

Discussion

We have developed catalytic stereoselective annulation reactions that afford spirooxindole pyran polycycles. We have shown that the formation of the pyran ring through the formation of C–C and C–O bonds that result in the formation of the polycyclic system provides stereoselectivities distinct from the formation of the cyclohexane ring through the formation of C–C bonds that lead to the all-carbon polycycles from the same spiro[4,5]decane derivatives. The differences in the reaction stereoselectivities may originate from the differences in C–C and C–O bond lengths. The details of the mechanisms of the reactions that lead to the selective formation of the complex polycyclic products and of the differences in the stereoselectivities between the formation of the pyran polycycles and the formation of previously reported all-carbon polycycles are under investigation. The method reported here provides a way to access spirooxindole pyran polycycles useful for the development of bioactive molecules and related research.

Methods

Synthetic procedures

Isomerization experiments

See Supplementary Tables 1–5 and Supplementary Figures 1–9.

Characterization

For NMR spectra and HPLC chromatograms see Supplementary Figures 10–136.

Crystallography

X-ray crystallographic data of compounds (±)-3a and (±)-4a are available in Supplementary Data 1–2.

Data availability

X-ray crystallographic data of compounds (±)-3a and (±)-4a have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC); compound (±)-3a (CCDC 1906368) and compound (±)-4a (CCDC 1906367). These data can be obtained free of charge from the CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data in support of the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Reddy, D. S. & Kutateladze, A. G. Structure revision of an acorane sesquiterpene cordycepol A. Org. Lett. 18, 4860–4863 (2016).

Shi, Q. W., Sauriol, F., Lesimple, A. & Zamir, L. O. First three examples of taxane-derived di-propellanes in taxus canadensis needles. Chem. Commun. 544–545 (2004).

Tamber, U. K., Kano, T., Zepernick, J. F. & Stoltz, B. M. Convergent and diastereoselective synthesis of the polycyclic pyran core of saudin. J. Org. Chem. 71, 8357–8364 (2006).

Yokoshima, S., Tokuyama, H. & Fukuyama, T. Enantioselective total synthesis of (±)-gelsemine: Determination of its absolute configuration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 4073–4075 (2000).

Madin, A. et al. Use of the intramolecular heck reaction for forming congested quaternary carbon stereocenters. stereocontrolled total synthesis of (±)-gelsemine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 18054–18065 (2005).

Vetica, F., Chauhan, P., Dochain, S. & Enders, D. Asymmetric organocatalytic methods for the synthesis of tetrahydropyrans and their application in total synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 1661–1674 (2017).

Ye, N., Chen, H., Wold, E. A., Shi, P.-Y. & Zjou, J. Therapeutic potential of spirooxindoles as antiviral agents. ACS Infect. Dis. 2, 382–392 (2016).

Cheng, D., Ishihara, Y., Tan, B. & Barbas, C. F. III Organocatalytic asymmetric assembly reactions: synthesis of spirooxindoles via organocascade strategies. ACS Catal. 4, 743–762 (2014).

Zhang, L.-L., Zhang, J.-W., Xiang, S.-H., Guo, Z. & Tan, B. Remote control of axial chirality: synthesis of spirooxindole-urazoles via desymmetrization of ATAD. Org. Lett. 20, 6022–6026 (2018).

Wang, L. et al. Switchable access to different spirocyclopentane oxindoles by N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed reactions of isatin-derived enals and N-sulfonyl ketimines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 8516–8521 (2017).

Chaudhari, P. D., Hong, B.-C. & Lee, G.-H. Organocatalytic enantioselective Michael–Michael–Michael–aldol condensation reactions: control of six stereocenters in a quadruple-cascade asymmetric synthesis of polysubstituted spirocyclic oxindoles. Org. Lett. 19, 6112–6115 (2017).

Yoon, H., Rolz, M., Landau, F. & Lautens, M. Palladium-catalyzed spirocyclization through C-H activation and regioselective alkyne insertion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 10920–10923 (2017).

Wu, H.-R. et al. FeCl3-mediated radical tandem reactions of 3-benzyl-2-oxindoles with styrene derivatives for the stereoselective synthesis of spirocyclohexene oxindoles. Org. Lett. 18, 1382–1385 (2016).

Zhao, X. et al. The asymmetric synthesis of polycyclic 3-spirooxindole alkaloids via the cascade reaction of 2-isocyanoethylindoles. Chem. Commun. 51, 16076–16079 (2015).

Jiang, K., Jia, Z.-J., Yin, X., Wu, L. & Chen, Y.-C. Asymmetric quadruple aminocatalytic domino reactions to fused carbocycles incorporating a spirooxindole motif. Org. Lett. 12, 2766–2769 (2010).

Lu, Y.-L., Sun, J., Xie, Y.-J. & Yan, C.-G. Molecular diversity of the cyclization reaction of 3-methyleneoxindoles with 2-(3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-ylidene)malononitriles. RSC Adv. 6, 23390–23395 (2016).

Chintalapudi, V., Galvin, E. A., Greenaway, R. L. & Anderson, E. A. Combining cycloisomerization with trienamine catalysis: a regiochemically flexible enantio- and diastereoselective synthesis of hexahydroindoles. Chem. Commun. 52, 693–696 (2016).

Tan, B., Candeias, N. R. & Barbas, C. F. III Construction of bispirooxindoles containing three quaternary stereocentres in a cascade using a single multifunctional organocatalyst. Nat. Chem. 3, 473–477 (2011).

Chen, P. et al. Auto-tandem cooperative catalysis using phosphine/palladium: reaction of Morita–Baylis–Hillman carbonates and allylic alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 4036–4040 (2019).

Zhang, H. et al. Diversified cycloisomerization/Diels-Alder reactions of 1,6-enynes through bimetallic relay asymmetric catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 5381–5385 (2019).

Huang, J.-R., Sohail, M., Taniguchi, T., Monde, K. & Tanaka, F. Formal (4 + 1) cycloaddition and enantioselective Michael–Henry cascade reactions to synthesize spiro[4,5]decanes and spirooxindole polycycles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5853–5857 (2017).

Liu, Y.-L. et al. One-pot tandem approach to spirocyclic oxindoles featuring adjacent spiro-stereocenters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 13735–13739 (2013).

Zhou, R. et al. Organocatalytic cascade reaction for the asymmetric synthesis of novel chroman-fused spirooxindoles that potently inhibit cancer cell proliferation. Chem. Commun. 51, 13113–13116 (2015).

Mao, H. et al. Organocatalytic oxa/aza-Michael–Michael cascade strategy for the construction of spiro [chroman/tetrahydroquinoline-3,3′-oxindole] scaffolds. Org. Lett. 15, 4062–4065 (2013).

Zhao, K. et al. Organocatalytic domino oxa-Michael/1,6-addition reactions: asymmetric synthesis of chromans bearing oxindole scaffolds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 12104–12108 (2016).

Kalvacherla, B., Batthula, S., Balasubramanian, S. & Palakodety, R. K. Transition-metal-free cyclization of propargylic alcohols with aryne: synthesis of 3-benzofuranyl-2-oxindole and 3-spirooxindole benzofuran derivatives. Org. Lett. 20, 3824–3828 (2018).

Yang, Z.-T., Zhao, J., Yang, W.-L. & Deng, W.-P. Enantioselective construction of CF3-containing spirooxindole γ-actones via organocatalytic asymmetric Michael/lactonization. Org. Lett. 21, 1015–1020 (2019).

Zhu, L. et al. Enantioselective construction of spirocyclic oxindole derivatives with multiple stereocenters via an organocatalytic Michael/aldol/ hemiacetalization cascade reaction. Org. Lett. 18, 2387–2390 (2016).

Peng, J., Ran, G.-Y., Du, W. & Chen, Y.-C. Divergent cyclization reactions of Morita–Baylis–Hillman carbonates of 2-cyclohexenone and isatylidene malononitriles. Org. Lett. 17, 4490–4493 (2015).

Zhao, S., Lin, J.-B., Zho, Y.-Y., Liang, Y.-M. & Xu, P.-F. Hydrogen-bond-directed formal [5 + 1] annulations of oxindoles with ester-linked bisenones: facile access to chiral spirooxindole δ-lactones. Org. Lett. 16, 1802–1805 (2014).

Du, D. et al. A novel diketopyrrolopyrrole (DPP)-based [2]rotaxane for highly selective optical sensing of fluoride. Org. Lett. 14, 1274–1277 (2012).

Wang, J., Crane, E. A. & Scheidt, K. A. Highly stereoselective Brønsted acid catalyzed synthesis of spirooxindole pyrans. Org. Lett. 13, 3086–3089 (2011).

Cui, H.-L. & Tanaka, F. Catalytic enantioselective formal hetero-Diels–Alder reactions of enones with isatins to give spirooxindole tetrahydropyranones. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 6213–6216 (2013).

Peng, J.-B. et al. Efficient oxa-Diels-Alder/semipinacol rearrangement/aldol cascade reaction: short approach to polycyclic architectures. Org. Lett. 17, 1014–1017 (2015).

Liu, G., Shirley, M. E., Van, K. N., McFarlin, R. L. & Romo, D. Rapid assembly of complex cyclopentanes employing chiral, α,β-unsaturated acylammonium intermediates. Nat. Chem. 5, 1049–1057 (2013).

Xu, K., Lalic, G., Sheehan, S. M. & Shair, M. D. Dynamic kinetic resolution during a cascade reaction on substrates with chiral all-carbon quaternary centers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 2259–2261 (2005).

Bocknack, B. M., Wang, L.-C. & Krishe, M. J. Desymmetrization of enone-diones via rhodium-catalyzed diastereo- and enantioselective tandem conjugate addition-aldol cyclization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 101, 5421–5424 (2004).

Corbett, M. T. & Johnson, J. S. Dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformations of β-stereogenic α-ketoesters by direct aldolization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 255–259 (2014).

Zhang, H., Lin, S. & Jacobsen, E. N. Enantioselective selenocyclization via dynamic kinetic resolution of seleniranium ions by hydrogen-bond donor catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16485–16488 (2014).

Chouthaiwale, P. V., Aher, R. D. & Tanaka, F. Catalytic enantioselective formal (4 + 2) cycloaddition by aldol-aldol annulation of pyruvate derivatives with cyclohexane-1,3-diones to afford functionalized decalins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13298–13301 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Michael Chandro Roy, Research Support Division, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University for mass analyses. This study was supported by the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. and F.T. conceived the work, M.S. conducted the experiments, F.T. directed the research, M.S. and F.T. analyzed the data, and M.S. and F.T. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sohail, M., Tanaka, F. Dynamic stereoselective annulation via aldol-oxa-cyclization cascade reaction to afford spirooxindole pyran polycycles. Commun Chem 2, 73 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0177-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0177-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.