Abstract

Low electrical conductivity caused by low degree of π-conjugation and structural disorders induces critical limitations in electronic applications of covalent organic frameworks (COFs). Here we focus on improving the electrical properties of COFs by synthesis of highly conjugated and crystalline COF (hcc-COF). Addition of a small amount of water and acetic acid induces the efficient reversible dynamic imine condensation reaction that is required to obtain uniform and crystalline products. Also, simulated sunlight irradiation facilitates the reversible imine condensation reaction, and achieves formation of hcc-COF with high-yield within short reaction time. The obtained hcc-COF has an extended π-conjugated structure along the lateral direction and an inclined stacking structure. The intrinsic electron transport properties along the in-plane direction are evaluated using a hcc-COF film grown on a water surface from a polarity-controlled precursor solution. To the best of our knowledge, our hcc-COF film shows the highest reported electrical conductivity for highly conjugated organic porous polymers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Continuously linked π-extended molecular systems have been intensively studied after the discovery of graphene1,2. Inspired by the unique and remarkable electrical and optical properties of graphene3,4, bottom-up approaches to synthesize highly conjugated materials have been attempted to increase the ease of modifying structure and properties5,6. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) that can be obtained by condensation reaction of organic monomers are good candidate for the realization of highly conjugated materials that exhibit homogenous porous structure with structural tunability, and multifunctional properties7,8,9,10. Especially, two-dimensional (2D) COFs are covalently bonded in the lateral direction and held together in the vertical direction by van der Waals interactions11,12,13,14. Due to the different characteristics in the lateral and vertical crystallographic directions, 2D COFs are regarded as two-dimensional layered materials, as are graphene and hexagonal boron nitride15,16,17,18. However, because of electron localization and abundant defects generated by the low molecular conjugation of π-electrons and insufficient reversible self-healing process19,20, COFs have low electric conductivity, so their value in electrical applications is limited. To improve their electrical and optical properties, highly conjugated COFs or doped COFs have been suggested19,21,22. However, their electrical conductivity is still too low to be useful for practical applications, mostly due to structural defects or low crystallinity. To increase the electrical conductivity of COFs, highly conjugated and crystalline COF (hcc-COF) with few structural defects must be obtained.

In this study, we synthesize and evaluate an hcc-COF, and study the effect of electron delocalization, especially for electrical properties along the in-plane direction in atomically thin hcc-COF 2D films. Our target hcc-COF is aza-conjugated micro-porous polymer (aza-CMP) that has been evaluated for applications as a supercapacitor and low-band-gap material23,24. However, all reported aza-CMPs are not crystalline but amorphous, so their structures are not known. The failure to crystallize aza-CMP seems to be largely due to harsh synthesis conditions, such as usage of sulfuric acid at high reaction temperature that induces fast imine condensation reaction, but disturbs reversible imine-exchanging process; as a result, numerous defects form an impair development of long-range structural order. Crystallinity in porous polymers, including COFs is one of the most important metrics of quality of the product such as homogeneity, degree of structural order and eventually degree of π-electron conjugation. Moreover, having crystalline highly conjugated polymers allows understanding and improvement of their electrical and optical properties. Therefore, we focus on synthesis of the hcc-COF that has a long-range ordered and perfectly p-orbital delocalized structure that is expected to induce outstanding electrical conductivity. Our strategy to obtain hcc-COF is to develop efficient control of the reversible imine-condensation reaction. To obtain a crystalline product in continuously linked molecular system, this reversible covalent bond formation is important because it allows continuous covalent bond formation/deformation process that is essential to obtain highly symmetric, stable and homogenous products21. Reversibility is especially important in the Schiff’s base reaction25,26,27, because amorphous or poorly crystalline materials are easily observed in polymers such as aza-CMP that containing imines13,28. The presence of water and the pH of precursor solution are important factors to obtain crystalline imine-based COF by an efficient reversible imine-condensation reaction20.

Herein, we induce an efficient imine formation/deformation reaction by adding a small amount of acid catalyst and water. Use of COF in practical applications requires an efficient synthesis method. To speed up the imine condensation reaction, we use light energy, which can prompt a reversible imine condensation reaction. Although the light-promoted imine condensation reaction has been studied for fundamental organic synthesis, their applications in multifunctional materials is quite rare29,30. Recently, we reported a light-promoted synthesis of poly-imine-based COF (pi-COF) and prove that photon energy not only accelerate imine condensation reaction but also facilitate transformation from amorphous imine containing precipitates to crystalline COF through fast reversible dynamic imine condensation reaction17,31. We adapt this synthesis method, which yields hcc-COF at room temperature within 3 h. We also synthesize atomically thin hcc-COF 2D film on a water surface; the film has highly conjugated π-electrons along the in-plane direction, so electrons can move freely and the films show outstanding electrical conductivity.

Results

Synthesis of the hcc-COF

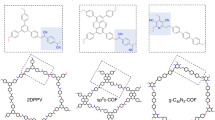

The hcc-COF was produced by mixing precursors, 1,2,4,5-benzenetetramine (BTA) and hexaketocyclohexane (HCH) in a lab-made quartz vial that is designed to minimize unintended light absorption (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a), then dissolving them in methanol/mesitylene mixed solvent, and finally adding a small amount of deionized (DI) water and acetic acid to induce an efficient reversible imine condensation reaction. Then the reaction was conducted by irradiating the mixture with simulated sunlight at wavelengths of 200–2500 nm17 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). After 3 h of irradiation, black precipitates were collected (Supplementary Fig. 2) and rinsed in methanol and mesitylene. Detailed experimental procedure was described in the “Methods” section. The average reaction yield of 10 samples was 79.16 %. The crystal structure of the product was determined by wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) analysis (Fig. 1b). Due to the efficient reversible condensation reaction that was induced by the added acid catalyst and water, our product showed high crystallinity, which is clearly different from previously reported amorphous Aza-CMPs23. Additionally, we measured powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern of the hcc-COF powder to further confirm the crystal structure of newly obtained COF, which shows almost identical peak shapes and positions of (100) and (110) planes as WAXD spectra shown in Fig. 1b (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Synthesis and characterization of resulting hcc-COF. a Molecular structure of hcc-COF obtained by condensation reaction between two precursors. b Measured WAXD pattern (orange), Pawley-refined diffraction pattern (green), and difference (gray) between measured and refined diffraction. Inset: two-dimensional WAXD image. c Top and d side view of hcc-COF with inclined stacking structure. e TEM image (scale bar = 500 nm) and f electron diffraction pattern of hcc-COF (scale bar = 1/1 nm). g EELS mapping images of carbon and nitrogen K-edges of hcc-COF (scale bar = 50 nm)

To confirm the necessities of water and acetic acid in the formation of crystalline hcc-COF, control experiments were conducted under the same synthesis condition, but without acid catalyst, without water, or without both (Supplementary Fig. 4). Crystalline hcc-COF could be obtained only in the presence of both acid catalyst and water. Reaction in darkness for 3 h with water and acetic acid yielded only amorphous product; this result is consistent with our previous findings that light energy facilitates the reversible imine condensation reaction (Supplementary Fig. 5a). The hcc-COF with poor crystallinity was obtained in the absence of light energy even after reaction for 5 days (Supplementary Fig. 5b); this result implies that imine condensation reaction occurs very slowly in darkness in the presence of acid catalyst and water. We also confirmed that the temperature increase by the light irradiation is negligible, as the change was less than 3 °C for 24 h light irradiation using solar simulator (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Crystal structure analysis of the resulting hcc-COF

Pawley refinement of diffraction data (Fig. 1b, green line) was used to solve the crystal structure of hcc-COF. One of the most difficult tasks in confirming the structure of newly obtained COF is to determine its stacking structure. Due to different bond formation process and interlayer interactions such as dipole-dipole and Van der Waals interactions, COFs can have various types of stacking structures. Stacking structures of COFs have been classified into eclipsed AA, serrated AA, inclined AA and AB stacking that have distinctive diffraction patterns32,33,34. Therefore, to identify the stacking structure of hcc-COF, we examined four possible crystal models and calculated each diffraction pattern (Supplementary Figs. 7–10). Obtained Rwp values which are sum of squared difference between the observed and computed value of each stacking structure are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The measured diffraction pattern of hcc-COF closely matched to the inclined AA stacking structure that has a larger lattice distance in (100) plane than other stacking structures. This result implies that strong dipole-dipole repulsion of nitrogen in pyrazine functional groups between the layers induces the inclined AA stacking. The Pawley-refined diffraction pattern (Fig. 1b, green) differed very little (Fig. 1b, grey line) from the measurements (Rwp = 4.84%).

The spectra show main intense peaks at 2θ = 7.39° and 2θ = 9.88°; their positions correspond to the crystal planes of (100) and (110) for hcc-COF. The other four weak peaks at 2θ = 14.82°, 15.75°, 26.46° and 28.34° also matched to the (200), (210), (301) and (001) planes, respectively. The optimized unit cell parameter is a = b = 15.784 Å, c = 4.75 Å, α = β = 49.83°, γ = 60.00°, having P1 space group. In the AA inclined stacked hcc-COF, the top (Fig. 1c) and side view (Fig. 1d) show that nitrogen atoms are placed close to the carbon of pyrazine functional group of adjacent layers to minimize dipole-dipole repulsion. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images (Fig. 1e, f) confirmed the crystallographic information. The hcc-COF was readily damaged by the electron beam, so we could not obtain TEM images that had atomic resolution, but the electron diffraction pattern of hcc-COF shows a first peak at 1.22 nm and a second peak at 0.61 nm of lattice parameter, which are well matched with lattice parameters of the (100) plane (1.19 nm) and of the (200) plane (0.60 nm) in WAXD pattern (Fig. 1b).

Spectroscopic and physical characterizations of the hcc-COF

Elemental analysis was accomplished using electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS, Fig. 1g) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, Supplementary Fig. 11). The results confirm that hcc-COF is uniformly composed of carbon and nitrogen atoms. The large amount of carbon in EDS spectrum is caused by the carbon film that was used to cover the TEM grid.

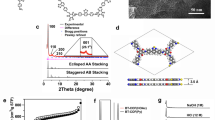

The chemical structure of the hcc-COF was analyzed spectroscopically. Raman spectra (Fig. 2a) of hcc-COF and BTA, and FT-IR spectra (Fig. 2b) of hcc-COF and HCH confirmed the disappearance of N–H and C = O functional groups, and the appearance of C = N and C = C chemical bonds, both of which indicate successful formation of newly appeared pyrazine functional groups by a dehydration reaction between the two precursors.

Spectroscopic analysis and electrical property measurement of hcc-COF. a Raman spectra of hcc-COF (orange) and benzenetetramine (blue). The four main stretching bands of hcc-COF and two main stretching bands of BTA are marked as orange asterisks and blue triangles, respectively. b FT-IR spectra of hcc-COF (orange) and hexaketocyclohexane (gray) showing the appearance of imine functional group. c I–V curve of hcc-COF in ambient condition; inset: isosurface of electron density. d Temperature dependent I–V characteristics at 100 ≤ T ≤ 250 ≤ °C for DC voltage 0 to 30 V

To further confirm the identity of chemical species that were detected in the Raman spectra, we performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations using Dmol3 modules in Material Studio program packages (see “Method” section). The two main bands at 1378.18 and 1541.69 cm−1 (Fig. 2a, blue triangle) in the Raman spectrum of BTA agree well with the calculated vibration energies of primary amine, specifically, the asymmetric stretching (1371.49 cm−1) and scissoring (1547.28 cm−1) vibrational modes, which did not appear in the Raman spectrum of hcc-COF. The four stretching bands (Fig. 2a, orange asterisk) in the Raman spectrum of hcc-COF are related to vibrations of newly-formed pyrazine, which contains a highly conjugated part of hcc-COF; this observation means that the imine condensation reaction occurred successfully under our synthesis condition. The band positions are 1230.96, 1430.35, 1471.28 and 1507.94 cm−1 that are all close (within 1–8 cm−1) to calculated vibration energies of a unit cell of hcc-COF (Raman vibrational modes of hcc-COF and BTA: Supplementary Movies 1–6). Because HCH is Raman inactive due to its highly symmetric structure (Supplementary Fig. 12), it gives no Raman signal; instead, we confirmed the disappearance of carbonyl functional group of the hcc-COF by FT-IR spectroscopy.

The IR spectrum (Fig. 2b) of the hcc-COF shows aromatic C = C and C = N bonds that appeared in the newly-formed pyrazine functional groups of hcc-COF. The broad vibrational band of water observed at wavenumbers 3408.12 ~ 3022.37 cm-1 are assigned to adsorbed water molecules in hcc-COF pores. The disappearance of the C = O vibrational band at 1639 cm-1 that was observed in the HCH precursor means that the reaction reached completion, and hcc-COF formed successfully24.

Also, we measured 13C solid NMR spectrum of hcc-COF powder, from which we confirmed three types of carbon (Supplementary Fig. 13); the peak appeared at 140.66 ppm corresponds to the carbon of phenyl ring adjacent to phenazine functional group. Also, the peaks appeared at 129.51 and 105.54 ppm are related with ortho and para carbons of phenyl ring, respectively. Our result is well matched with previously reported aza-CMP that has an identical local structure with hcc-COF20.

To confirm the porous structure of resulting hcc-COF, we measured N2 adsorption isotherm, pore size and surface area using Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) measurement. Supplementary Fig. 14a is N2 adsorption/desorption graph of the hcc-COF powder indicating type I isotherm having adsorbed volume of 300 Va/Cm3(STP)g−1 at relative pressure (P/P0) of 0.5. The surface area was calculated to be 598 m2/g by the BET model. Supplementary Fig. 14b is a pore size distribution of the hcc-COF powder that shows pore size of 1.39 nm, which is well-matched with the pore size of analyzed hcc-COF structure from diffraction analysis (1.37 nm).

Electrical property measurements of the hcc-COF

One important predictable property of highly conjugated polymer is its increase of electrical conductivity because overlapped p-orbitals of hcc-COF sheets form a highly delocalized π-electron environment that can increase overall stability of the material and facilitate charge transport, we measured the electrical conductivity of hcc-COF. For the measurements, hcc-COF powder was pelletized using manual press machine (Pike Technologies). Resulting pellets having diameter and thickness of 7 and 0.03 mm, respectively, were transferred onto a SiO2/Si substrate. For the better contact between electrode and sample, we used silver paste as efficient liquid electrode (Supplementary Fig. 15). The current-voltage (I–V) curve (Fig. 2c) of the hcc-COF pellet from −5.0 to 5.0 V was linear, which is a sign of Ohmic contact between sample and electrode. The calculated electrical conductivity of the hcc-COF pellet was 2.22 × 10−3 S/m, which is the highest value yet reported for conductive bulk COFs, and is comparable with iodine-doped sp2c-COF, which holds the record high conductivity among reported doped COFs (Supplementary Table 2)19,22,24,35,36. Especially, aza-CMP that was synthesized for the same target material of our hcc-COF shows two orders of magnitude lower electrical conductivity than our hcc-COF24. This large conductivity difference is mainly due to the crystallinity of the product, because hcc-COF allows long-range π-conjugation and ordered stacking structure. To ensure reproducibility of conductivity measurement, we tested the ten hcc-COF pellets which were synthesized in different batches using same synthesis condition. In the case of bulk hcc-COF powder, nine out of ten pellets showed same order of conductivity value and one sample showed an insulating property, which is seems to be due to the contact problem between silver paste and hcc-COF pellet. The average conductivity of nine samples was 2.24 × 10−3 S/m. The high electrical conductivity (2.34 × 10−3 S/m) was also observed in the hcc-COF pellet on an insulating glass substrate, which refer their high electrical conductivity of hcc-COF was not affected by the substrate.(Supplementary Fig. 16)

Before measuring electrical conductivity change by increasing temperature up to 250 °C, we confirmed the thermal stability of hcc-COF by monitoring weight loss according to the temperature increase using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (Supplementary Fig. 17). The weight loss of 8.74% at around 100 °C shows the presence of water molecules in the hcc-COF. After water evaporation, the hcc-COF shows high thermal stability up to 400 °C, which is higher than that of the precursors (BTA (150 °C) and HCH (100 °C)), and previously reported aza-conjugated micro-porous polymer24,37, indicating the formation of robust and crystalline COF. The electrical conductivity of hcc-COF changed with temperature T. The current was unstable due to adsorption of water at T ≤ 100 °C (Supplementary Fig. 18), the conductivity gradually increased according as T increased from 100 to 250 °C (Fig. 2d); this trend indicates that hcc-COF is a semiconductor, and has reasonable thermal stability.

Sy3nthesis of the 2D hcc-COF film

The electrical property along the in-plane direction of hcc-COF is an indication of its ability to conduct electrons through its extended π-conjugation system. Recently, we reported formation of atomically thin and highly-oriented 2D poly-imine-based COF film (2D pi-COF film) that was obtained via uniform floating of polarity-controlled precursor solution on a water surface followed by light irradiation17. By modifying the method, we obtained hcc-COF 2D film using precursor solution of 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP), mesitylene, chloroform and acetic acid, followed by irradiation with simulated sunlight. Detailed synthesis procedure is described in the Supplementary Information. After water rinsing and annealing of transferred hcc-COF films, we confirmed the absence of residual precursors using Raman and FT-IR measurement by observing disappearance of amine and carbonyl vibrational bands, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 19). It should be noted that due to water miscibility of methanol, we changed precursor solvent from methanol to NMP, but still yielded hcc-COF successfully (Supplementary Fig. 20). The water surface after dropping precursor solution was photographed (Supplementary Fig. 21).

Optical microscopy image (Fig. 3a) of 2D hcc-COF showed a clean, defect-free, and continuous surface. The inset of Fig. 3a is a 2-inch SiO2/Si wafer covered with hcc-COF film. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) showed (Fig. 2b) the thickness of hcc-COF film to be 3.8 nm, which corresponds to nine layers of hcc-COF. We note that the layer number control of 2D COF film using polarity-controlled precursor solution is one of the important advantages of our synthetic method as we previously reported31. In the case of hcc-COF, we also successfully obtained mono-layer hcc-COF film by controlling concentration and loading volume of the precursor solution. Detailed synthesis procedure is described in the Method part. The thickness of the hcc-COF film was 0.72 nm (Supplementary Fig. 22), indicating a one-molecular layer thickness of COFs15,38.

Characterization of obtained hcc-COF film. a Optical microscopy image of hcc-COF film (scale bar = 200 μm). Inset: photograph of hcc-COF film covering 2-inch SiO2/Si substrate. b AFM image and height profile of hcc-COF film (scale bar = 1 μm). c I–V characteristics of hcc-COF film at 50 ≤ T ≤ 210 °C at DC voltage 0 to 10 V. d On-off switching behavior upon light irradiation of hcc-COF film as a function of time at a bias voltage of 0.1 eV

Characterizations of the hcc-COF film

Chemical structure and morphology were determined using Raman spectroscopy and TEM. The Raman spectrum of hcc-COF film (Supplementary Fig. 23) showed intense bands at 1511.58 and 1234.78 cm−1, which agree well with the bands observed in the spectrum of bulk hcc-COF, and which are assigned to the pyrazine-bearing conjugated part. The newly appeared pyrazine functional group of hcc-COF film means efficient imine condensation reaction successfully occurred on the water surface as well. The TEM image of hcc-COF film showed highly uniform and atomically thin structure (Supplementary Fig. 24a). Due to low stability of the hcc-COF film against electron beam irradiation, specific lattice planes could not be observed, but the porous nature and hexagonal-shaped diffraction pattern were observed (Supplementary Fig. 24b, c). The 1.2 nm of lattice distance of obtained electron diffraction pattern is well matched with (100) plane observed in WAXD data of the hcc-COF powder (Fig. 1b).

Electrical property measurements of the hcc-COF film

To confirm the electrical properties of hcc-COF 2D film, field effect transistor (FET) type-electronic devices were fabricated (see Method part and Supplementary Fig. 25). We used copper wire as a photo mask for the deposition of metal electrodes. After metal deposition, we annealed resulting device at 100 °C, which is one of the effective and common post treatment techniques in device fabrication because it can reduce the interface trap density and enhances the bonding between metal and semiconductor, that decreases the contact resistance and forms ohmic contact39,40. We characterized interface of metal electrode and hcc-COF film using EDS. Supplementary Fig. 26a is dark-field TEM image showing clear interface between gold and hcc-COF film covered by copper wire during metal deposition process. From EDS mapping of gold element, we confirmed that gold was not existed in hcc-COF channel at all, which means that gold was neither penetrated in the pore of COF during metal evaporation nor diffused into channel during metal deposition and annealing process (Supplementary Fig. 26b). The resulting device had channel length of 68.6 μm (Supplementary Fig. 26c) and channel width of 1 cm. For comparison, we fabricated electronic devices of 2D pi-COF film that has a partially-conjugated structure. For the conductivity measurement, we used a probe station and a semiconductor analyzer. The two gold probe tips were directly contacted to the metal electrodes of device as shown in Supplementary Fig. 27. The chemical structure and I–V characteristic of pi-COF is described in Supplementary Fig. 28. The electrical conductivity was 0.40 S/m for the hcc-COF 2D film and 5.51 × 10−3 S/m for the 2D pi-COF film as calculated from the I–V curves (Supplementary Figs. 29 and 28b, respectively). The electrical conductivity of hcc-COF 2D film is the highest yet observed among bulk COFs and COF films, and among iodine-doped and TTF-doped COFs (Supplementary Table 2)19,22,36. We tested 10 samples of hcc-COF film synthesized in different batches. Among the ten samples, eight samples showed similar electrical property, of which average conductivity value was 0.42 S/m. We suspect that the other two insulating films may come from structural disorder or physically generated defects during the device fabrication. We also measured conductivity of the hcc-COF film transferred on an insulating quartz substrate, which showed similar conductivity (0.38 S/m) to the average conductivity of hcc-COF films (0.42 S/m) transferred on a SiO2/Si substrate (Supplementary Fig. 30).

The oriented structure along the highly conjugated (in-plane) direction of hcc-COF film showed higher electrical conductivity than bulk hcc-COF; this difference means that electron transport occurs along the in-plane direction through the highly delocalized π-electron conjugated system. We believe that this result confirms that high degree of conjugation with high crystallinity are important factors to increase the electrical conductivity of COF. The I–V characteristics of hcc-COF film at 50 ≤ T ≤ 210 °C showed a gradual increase in conductivity with T; this result confirms the semiconducting nature of hcc-COF film (Fig. 3c). Different with hcc-COF pellet, we could observe stable conductivity increase below T ≤ 100 °C in the hcc-COF film device. This difference is caused by different device fabrication process. To measure conductivity of hcc-COF pellets, we attached silver paste without any additional annealing under ambient condition. On the other hand, for the COF film device fabrication, samples were exposed to ultra-high vacuum (~10−7 torr) for the metal deposition on the hcc-COF film, and annealed at 100 °C to improve contact between electrode and film. Therefore, water present in the hcc-COF films evaporated during the device fabrication process, while water should present in the pellet samples.

This semiconducting hcc-COF film shows rapid photo-response to laser-driven white light irradiation (wavelengths 170 ≤ λ ≤ 2100 nm) (Fig. 3d). At a constant bias voltage of 0.1 V, and the current was ~1.4 times higher after irradiation. This result suggests that conducting hcc-COF film have a potential for practical applications in organic electronic devices.

Discussion

Herein, we demonstrated light-promoted synthesis of highly conjugated and crystalline COF (hcc-COF) in both bulk-powder and 2D-film forms by efficient reversible imine condensation reaction by using small amount of acid catalyst and water. The crystal structure of hcc-COF was confirmed by Pawley refinement that shows highly conjugated structure along the in-plane direction and inclined stacking structure along the out-of-plane direction. Also, successful formation of a pyrazine-bearing conjugated structure was confirmed by spectroscopic analysis and DFT calculation. We showed that hcc-COF has a semiconducting property with high conductivity (2.22 × 10−3 S/m). The transport property only along the π-conjugation direction was examined using a FET-type electronic device of hcc-COF film. The measured electrical conductivity of hcc-COF film is 0.40 S/m, which is the highest yet reported for COFs. We believe that these findings can contribute to the development of novel strategies to synthesize crystalline and high-quality COFs, which may have a variety of electronic and optical applications.

Methods

Light-promoted synthesis of bulk hcc-COF

1,2,4,5-Benzenetetramine tetrahydrochloride, hexaketocyclohexane octahydrate, 1,4-dioxane, methanol and 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Mesitylene, chloroform and acetic acid were purchased from Samchun (Seoul, Korea), J.T. Baker and Alfa-Aesar, respectively. All chemicals were used without further purification. In addition, a lab-made quartz vial (Supplementary Fig. 1a, diameter ≈ 2 cm, height ≈ 5.5 cm) specially designed for an efficient light absorption was used for the synthesis of hcc-COF.

A concentration of 42 mg of 1,2,4,5-Benzenetetramine tetrahydrochloride (0.1 mol) and 31 mg of hexaketocyclohexane octahydrate (0.15 mol) were added in the quartz vial and sealed using a rubber septum and parafilm. Then, the precursors containing quartz vial was purged using argon gas for 1 h. After purging, 1:1 volume ratio of methanol/mesitylene mixed solvents were added to dissolve the precursors in under argon atmosphere (Total 12 mL). After 30 min of sonication, 2.4 mL of distilled water (Milli-Q system, Millipore) and 3.6 mL of acetic acid were injected into the vial to induce efficient reversible imine condensation reaction. Then, the reaction was carried out by irradiating simulated sunlight at wavelengths of 200–2500 nm (Fig. S1b, Oriel Class AAA Solar simulator, Newport, AM 1.5 G illumination with an intensity of 50 mW/cm2). Resulting powder precipitates were rinsed three times using methanol and mesitylene. We note that for the synthesis of the hcc-COF obtained by usage of NMP, we added 1:1 volume ratio of NMP/mesitylene mixed solvents instead of MeOH/mesitylene. All other experimental procedures are identical.

Light-promoted synthesis of hcc-COF film

A precursor solution was prepared as followings: 6.2 mg of 1,2,4,5-Benzenetetramine tetrahydrochloride (0.02 mol) and 8.4 mg of hexaketocyclohexane octahydrate (0.03 mol) were dissolved in a scintillation vial containing 1 mL of NMP. After sonication for 1 h, the solution was filtered using a syringe filter of 0.02 μm pore size (membrane filter, Whatman) to remove remaining undissolved precursors. Then, 1 mL of mesitylene, 0.5 mL of chloroform and 50 μL of acetic acid were added into the precursor solution to control the polarity of precursor solution. 50 μL of the filtered solution was carefully dropped on the water surface in a glass vessel. For the efficient imine condensation reaction, light was irradiated using a solar simulator for 1 h from the top of the reaction vessel. A photograph of water surface after dropping precursor solution is shown in Supplementary Fig. 21. After transfer of hcc-COF films into a desire substrate by fishing, we rinsed films for 30 s with DI-water to remove remained precursors which have good solubility in water (Supplementary Fig. 31). We tried to minimize solvent treatment to prevent further contaminations and structural defects of ultra-thin hcc-COF films. To dry trapped water between film and substrate, we annealed obtained hcc-COF film at 80 °C in ambient condition.

Structure confirmation and calculation of vibrational energies using Material Studio program

For the structure analysis, wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) patterns were obtained at 3 C beamline of Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL, Korea). For the indexing and Pawley refinement process, we used Reflex module of Accelrys Material Studio 2017 R2 (Biovia, San Diego, CA). The model structure was constructed and optimized using Dmol3 module of Material Studio program, and optimized unit cell information was used for initial parameters for refinement. The background was refined with a 20th-order polynomial and the peak profiles were refined by the Pseudo-Voigt function. The final Pawley refinement results are as followings: a: 15.783967 b: 15.783967 c: 4.752048 α: 49.83059° β: 49.83059° γ: 60.000°, Rwp: 4.84%, Rwp(w/o background): 4.79%. Also, we did DFT calculation using Dmol3 module of Material Studio program package to analyze vibrational energy of hcc-COF and precursors. We used optimized structure of precursors and hcc-COF.

Sample preparation for TEM measurement

Obtained hcc-COF film on the water surface was directly transferred by fishing to a 400-mesh copper TEM grid (Ted Pella, Inc.), then dried at 80 °C in the ambient condition for 30 min.

Device fabrication of hcc-COF 2D film

Synthesized hcc-COF films were transferred on a pre-cleaned SiO2/Si substrate and dried at 80 °C on a hot plate. We used Kapton tape and copper wire having a diameter of 50 μm as a photomask. The detailed experimental scheme is described in the Supplementary Fig. 25. Then, chromium and gold were deposited at a thickness of 5 and 20 nm, respectively. After device fabrication, the resulting devices were annealed at 100 °C in air to improve contact between metal and hcc-COF 2D film.

Characterization

The WAXD patterns confirm the crystal structure of product. Also, transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL, JSM-2200F) was used to confirm morphology and diffraction pattern of resulting hcc-COF. For the confirmation of chemical structure of hcc-COF and precursors, we measured Raman and Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra of hcc-COF and precursors. Raman spectra were measured using WITECH Alpha 300 R Raman spectrometer equipped with a 532 nm laser in ambient condition. Also, FT-IR spectra were measured using a Bruker Optics VERTEX 70 spectrometer. Also, the FT-IR spectra of hcc-COF films were obtained using a FT-IR spectrometer at reflection mode using a reflection module (Varain 670) and AFM images with height profiles were obtained using a Nanoscope IIIa (Digital Instrument Inc). NMR data were acquired on 400 MHz Solid stat NMR spectrometer (AVANCE III HD, Bruker, Germany) at KBSI Western Seoul center. Electrical transport properties were measured a probe station (M6VC, MS TECH) and a semiconductor analyzer (Keithley, 2600). The temperature during the measurement was controlled by a hot chuck controller (MST-1000H, MS TECH) equipped in the probe station.

Data Availability

All principal data with detailed exprimental procedure and characterization of this work are included in this article and its Supplementary Information or are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gutzler, R. & Perepichka, D. F. π-electron conjugation in two dimensions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16585–16594 (2013).

Cardenas, L. et al. Synthesis and electronic structure of a two dimensional π-conjugated polythiophene. Chem. Sci. 4, 3263–3268 (2013).

Castro Neto, A. H., Guinea, F., Peres, N. M. R., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109–162 (2009).

Zhu, Y. W. et al. Graphene and graphene oxide: Synthesis, properties, and applications. Adv. Mater. 22, 3906–3924 (2010).

Qian, H. L., Negri, F., Wang, C. R. & Wang, Z. H. Fully conjugated Tri(perylene bisimides): an approach to the construction of n-type graphene nanoribbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 17970–17976 (2008).

Liu, W. & Loh, K. P. Two-dimensional conjugated polymers based on C-C coupling. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 522–526 (2017).

Cote, A. P. et al. Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks. Science 310, 1166–1170 (2005).

Ding, S. Y. & Wang, W. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs): from design to applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 548–568 (2013).

Valentino, L., Matsumoto, M., Dichtel, W. R. & Marinas, B. J. Development and performance characterization of a polyimine covalent organic framework thin-film composite nanofiltration membrane. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 14352–14359 (2017).

Das, G. et al. Chemical sensing in two dimensional porous covalent organic nanosheets. Chem. Sci. 6, 3931–3939 (2015).

Spitler, E. L. & Dichtel, W. R. Lewis acid-catalysed formation of two-dimensional phthalocyanine covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 2, 672–677 (2010).

Mandal, A. K., Mahmood, J. & Baek, J. B. Two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks for optoelectronics and energy storage. Chemnanomat 3, 373–391 (2017).

Cote, A. P., El-Kaderi, H. M., Furukawa, H., Hunt, J. R. & Yaghi, O. M. Reticular synthesis of microporous and mesoporous 2D covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12914–12915 (2007).

Liao, H. P. et al. A 2D porous porphyrin-based covalent organic framework for sulfur storage in lithium sulfur batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 7416–7421 (2016).

Sahabudeen, H. et al. Wafer-sized multifunctional polyimine-based two-dimensional conjugated polymers with high mechanical stiffness. Nat. Commun. 7, 13461 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. Exfoliation of covalent organic frameworks into few-layer redox-active nanosheets as cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 4258–4261 (2017).

Kim, S., Lim, H., Lee, J. & Choi, H. C. Synthesis of a scalable two-dimensional covalent organic framework by the photon-assisted imine condensation reaction on the water surface. Langmuir 34, 8731–8738 (2018).

Xu, S. Q., Zhan, T. G., Wen, Q., Pang, Z. F. & Zhao, X. Diversity of covalent organic frameworks (COFs): A 2D COF containing two kinds of triangular micropores of different sizes. ACS Macro Lett. 5, 99–102 (2016).

Jin, E. Q. et al. Two-dimensional sp2 carbon-conjugated covalent organic frameworks. Science 357, 673–676 (2017).

Smith, B. J., Overholts, A. C., Hwang, N. & Dichtel, W. R. Insight into the crystallization of amorphous imine-linked polymer networks to 2D covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Commun. 52, 3690–3693 (2016).

Guo, J. et al. Conjugated organic framework with three-dimensionally ordered stable structure and delocalized π clouds. Nat. Commun. 4, 2736 (2013).

Cai, S. L. et al. Tunable electrical conductivity in oriented thin films of tetrathiafulvalene-based covalent organic framework. Chem. Sci. 5, 4693–4700 (2014).

Kou, Y., Xu, Y. H., Guo, Z. Q. & Jiang, D. L. Supercapacitive energy storage and electric power supply using an aza-fused π-conjugated microporous framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 8753–8757 (2011).

Briega-Martos, V. et al. An aza-fused π-conjugated microporous framework catalyzes the production of hydrogen peroxide. ACS Catal. 7, 1015–1024 (2017).

Zhu, L. J. & Zhang, Y. B. Crystallization of covalent organic frameworks for gas storage applications. Molecules 22, 1149 (2017).

Segura, J. L., Mancheno, M. J. & Zamora, F. Covalent organic frameworks based on Schiff-base chemistry: Synthesis, properties and potential applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 5635–5671 (2016).

Li, X. L. et al. Facile transformation of imine covalent organic frameworks into ultrastable crystalline porous aromatic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 9, 1988 (2018).

Schwab, M. G. et al. Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution through fully conjugated poly(azomethine) networks. Chem. Commun. 46, 8932–8934 (2010).

Jain, S., N., R., Pandey, R., Bakhru, M. & Kheradiya, B. Light induced condensation of some formyl derivatives of alkaloids with aromatic amines: Formation of Schiff;s base. J. Environ. Res. Dev. 6, 468–471 (2012).

Higashimoto, S., Nakai, Y., Azuma, M., Takahashi, M. & Sakata, Y. One-pot synthesis of imine from benzyl alcohol and nitrobenzene on visible-light responsive CdS-TiO2 photocatalysts. RSC Adv. 4, 37662–37668 (2014).

Kim, S. et al. Rapid photochemical synthesis of sea-urchin-shaped hierarchical porous COF-5 and its lithography-free patterned growth. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1700925 (2017).

Hayashi, T., Hijikata, Y., Page, A., Jiang, D. L. & Irle, S. Theoretical analysis of structural diversity of covalent organic framework: Stacking isomer structures thermodynamics and kinetics. Chem. Phy. Lett. 664, 101–107 (2016).

Fan, Y. et al. A Case Study on the influence of substitutes on interlayer stacking of 2D covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 5668–5672 (2017).

Laszlo, V. & Kowalczyk, T. Acene-linked covalent organic frameworks as candidate materials for singlet fission. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 10500–10507 (2016).

Duhovic, S. & Dinca, M. Synthesis and electrical properties of covalent organic frameworks with heavy chalcogens. Chem. Mater. 27, 5487–5490 (2015).

Nath, B. et al. A new azodioxy-linked porphyrin-based semiconductive covalent organic framework with I-2 doping-enhanced photoconductivity. CrystEngComm 18, 4259–4263 (2016).

Wang, L. et al. Photocatalytic oxygen evolution from low-bandgap conjugated microporous polymer nanosheets: a combined first-principles calculation and experimental study. Nanoscale 9, 4090–4096 (2017).

Dai, W. Y. et al. Synthesis of a two-dimensional covalent organic monolayer through dynamic imine chemistry at the air/water interface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 213–217 (2016).

Leong, W. S., Nai, C. T. & Thong, J. T. L. What does annealing do to metal-graphene contacts? Nano Lett. 14, 3840–3847 (2014).

Wang, Z. C. et al. Ohmic contacts on silicon carbide: the first monolayer and its electronic effect. Phys. Rev. B 80, 245303 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) was performed at 3 C Beamline of the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL), Korea. Observation of morphology and electron diffraction pattern using high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HR-TEM) were carried out at national institute for nanomaterials technology (NINT) in Pohang, Korea. This research was supported by the Veteran researcher grant (No. 2019R1A2C2004259) managed by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. and H.C.C. designed the overall experiments and analyzed the data together. S.K. performed all the experiments. S.K. and H.C.C. wrote the manuscript together.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S., Choi, H.C. Light-promoted synthesis of highly-conjugated crystalline covalent organic framework. Commun Chem 2, 60 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0162-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0162-z

This article is cited by

-

Ultra-fast supercritically solvothermal polymerization for large single-crystalline covalent organic frameworks

Nature Protocols (2024)

-

Factors affecting the electrical conductivity of conducting polymers

Carbon Letters (2023)

-

Recent progress in advanced covalent organic framework composites for environmental remediation

Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials (2023)

-

Intramolecular hydroxyl nucleophilic attack pathway by a polymeric water oxidation catalyst with single cobalt sites

Nature Catalysis (2022)

-

Catalyst-free nitro-coupling synthesis of azo-linked conjugated microporous polymers with superior aqueous energy storage capability

Science China Materials (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.