Abstract

Development of a structurally well-defined small molecule with a high oxygen reduction reaction catalytic activity is a key approach for the bottom-up design of a metal-free carbon-based catalysts for metal-air batteries and fuel cells. In this paper, we characterize the oxygen reduction reaction activities of trioxotriangulene derivatives, which are stable neutral radicals with high redox abilities, via rotating disk electrode measurements in alkaline aqueous solution. Among trioxotriangulene derivatives having various substituent groups, N-piperidinyl-substituted derivative mixed with acetylene black shows a high catalytic activity with the two-electron transferring process exceeding other derivatives and quinones. To reveal the correlation between molecular structure and catalytic activity, we discuss substituent effects on the redox ability of trioxotriangulene derivatives, and demonstrate that a molecule with electron-donating groups yields relatively higher catalytic activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) which is usually promoted by Pt catalyst is a very important reaction for clean energy production, such as metal-air batteries and fuel cells1. However, the scarcity and high cost of Pt seriously restrict its commercial application. Extensive efforts have so far been devoted to carbon-based ORR catalysts replacing expensive Pt-based catalyst2,3. Metal-doped carbon catalysts prepared by the pyrolysis of the mixture of transition metal salts and nitrogen/carbon-based precursors are well-known to show high ORR activity comparable with Pt catalysts4,5. Recently, metal-free carbon materials doped with heteroatoms such as nitrogen, boron, sulfur, and etc. have attracted increasing attention as efficient metal-free ORR catalysts. Since the first report on nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube in 20096, various heteroatom-doped metal-free carbon catalysts7 have been developed based on carbon nanotube6,8,9,10,11,12, graphene13, graphite14, and nanoshell carbon material namely carbon alloy catalyst15,16,17,18. These heteroatom-doped carbons are structurally undefined materials and not discrete, because they are prepared by the pyrolysis of small molecules or by doping heteroatoms into carbon atom framework. Recently, the mechanism and reactive sites of the ORR reaction on the nitrogen-doped carbon materials have been discussed based on the computational calculation19,20. However, the intrinsic heterogeneity of the materials used as catalyst has impeded attempts to disclose their mechanism experimentally.

Compared to heterogeneous carbon-based materials, ORR catalysts based on organic small molecules have distinct molecular structures and homogeneity. Therefore, the properties of the molecules themselves are reflected directly to the catalytic performance, and the reaction mechanism and the correlation between molecular structure and catalytic activity can be clearly discussed. In addition, since the electronic structure and conformation of the molecules can be controlled precisely, the catalytic performance can be adjusted through systematic chemical modification at the molecular level. Bottom-up design of small molecule-based ORR catalysts provides important knowledge for the understanding of active site and the material improvement also in the development of heterogeneous carbon-based material. ORR catalytic activity of small molecules has been studied since the first report in 1964 on the cobalt phthalocyanine complex21, and various metal complexes of porphyrin, phthalocyanine, 1,10-phenanthroline and their derivatives have been investigated as ORR catalysts22,23,24,25. Metal-free small molecule-based ORR catalysts have been also reported in methylviologen26 and porphyrin derivatives25,27, etc. In the anthraquinone process industrially utilized in the production of H2O2, O2 is reduced to H2O2 by mediating the redox of anthraquinone derivatives28. Quinone derivatives such as 9,10-phenanthrenequinone29 and 9,10-anthraquinone30 adsorbed on graphite electrode have also been investigated as ORR catalysts31,32,33. However, sufficient ORR catalytic activity was not obtained with these quinone-modified electrodes. In other cases, graphene quantum dots including a phenazine unit in the carbon framework has been recently reported to show high ORR catalytic activity34,35,36,37, though they were yet to be estimated at a small-molecule level, as is the case with other carbon fragment materials like g-C3N4.38 The π-conjugated polymers such as polyaryls39 and poly(aryl-acenaphthenequinonediimine)40 were reported to exhibit ORR catalytic activities.

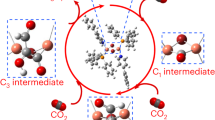

Trioxotriangulene (TOT, Fig. 1)41,42,43,44,45 is a polycyclic hydrocarbon functionalized with three oxo-groups, and its neutral radical is highly stable due to the delocalization of electronic spin on the whole 25π-electronic system. TOT derivatives also exhibit a four-stage redox ability generating thermodynamically stable polyanionic species, realizing a high performance Li-ion secondary battery42. The redox between open-shell neutral radical and close-shell monoanion species (Fig. 1) occurs at a relatively high potential around 0 V vs. ferrocene/ferrocenium (Fc/Fc+), and the redox potential can be flexibly tuned by the substituent groups R44.

In this paper, we investigate the ORR catalytic activities of TOT derivatives 1–5 (Fig. 1), and then the substituent effect is discussed in the relationship with redox potentials between their neutral radical and monoanion species. The N-piperidinyl-substituted TOT 5 with the lowest redox potential among 1–5 shows the highest catalytic activity among TOTs as well as anthraquinone derivatives. We believe that the present work highly contributes to the bottom-up tailored molecular design of metal-free ORR catalysts.

Results

Synthesis and redox properties of TOT derivatives

The new TOT derivatives 4 and 5 were synthesized by Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of the monoanion species of tribromo TOT 3− with corresponding boronic acid and amine, respectively, followed by the one-electron oxidation. Both neutral radicals of 1–5 and monoanion salts of 1−–4− were stable under air. On the other hand, the salt of monoanion 5− was gradually oxidized by air in both solution and solid states to generate the neutral radical 5. Figure 2 shows the differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) of 1–5 using DMF solution of tetra-n-butylammonium (n-Bu4N+) salts of corresponding monoanions, where oxidation peaks from monoanion to neutral radical were observed. The oxidation potential (Eox) became lower as the electron-donating ability of substituent groups became stronger with the order of Cl, Br (Eox = –0.04, −0.05 V vs. Fc/Fc+) > H (Eox = −0.10 V) > Ph (Eox = −0.33 V). The N-piperidyl derivative 5 showed the lowest potential (Eox = −0.40 V), causing the air oxidation of 5−.

The redox process from monoanion to neutral radical of 1–5 measured by DPV. Measurement was performed using their n-Bu4N+ salts of monoanion (3–5 mM) in DMF solution. O2 in the electrolyte solution was removed by Ar bubbling. The results were calibrated with Fc/Fc+. Peak potentials were presented by gray bars. The weak peaks of 2 and 3 around +0.1 V and drastic current change of 4 at −0.1 V are caused by the crystallization and/or adsorption of the resulting species on the glassy carbon electrode

ORR catalyst activities of TOT derivatives

To assess the ORR activity of TOT derivatives 1–5, cyclic voltammetry (CV) and linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) using a rotating disk electrode (RDE) were performed in 0.1 M KOH aqueous solution saturated with O2 at room temperature. The glassy carbon electrode coated with TOT/acetylene black (AB) catalysts in a 3:10 weight ratio was used for the measurements. Figure 3a shows the CV of 1–5/AB catalysts in the electrolyte solutions saturated with O2 or N2, and the results are summarized in Table 1. In the case of 1/AB catalyst, three reduction peaks were observed at 1.10, 0.60, and 0.36 V vs. RHE under an O2 saturated environment. The peak at 0.60 V disappeared when the electrolyte solution was purged with N2, indicating that this peak corresponded to the reduction of O2. The peaks at 1.10 and 0.36 V were observed also in the N2 saturated environment, and attributed to the redox processes of 1 from neutral radical to monoanion and from monoanion to radical dianion species, respectively. The ORR peak potential (EpORR) of 1/AB catalyst was very close to that of AB blank (0.61 V), suggesting that 1 has no or very weak activity as an ORR catalyst. The catalysts of chloro- and bromo-derivatives 2 and 3 exhibited similar behaviors with EpORR = 0.62 and 0.63 V, respectively. In the case of phenyl derivative 4, the ORR peak was observed at EpORR = 0.67 V, and a sharp reduction peak of 4 neutral radical was found at 0.81 V. EpORR of the N-piperidinyl derivative 5, 0.74 V, was the highest among TOT derivatives 1–5.

Electrochemical measurements of TOT/AB catalysts on an RDE. a CV curves in O2 or N2 saturated 0.1 M KOH aqueous solution. Dotted lines are CV curves in an N2 saturated condition. Gray bars indicate ORR peaks (EpORR). b LSV curves in O2 saturated condition. c Plots of EonORR from LSV and EpORR from CV measurements of TOT/AB catalysts. In CV and LSV measurements, scanning rates were 5 mV s−1

Figure 3b shows the disk-current density (j) curves of 1–5 in LSV measurement in comparison with AB blank. The ORR process was observed as the increase of j, and the catalytic activity was evaluated by the onset potential (EonORR) defined as a potential at j = –0.1 mA cm−2. EonORR of the AB blank electrode was +0.71 V vs. RHE. EonORR of 1–3/AB catalysts were almost the same to that of the AB blank, suggesting that these TOT derivatives do not work as the catalyst of ORR. On the other hand, the 4/AB catalyst showed a slight positive shift of the ORR process by ~0.03 V from the AB blank in addition to a sharp peak at 0.8 V originating from the reduction of 4 to monoanion 4−. In the case of 5/AB catalyst, a large positive shift, EonORR = 0.84 V, was observed. The results of CV and LSV measurements of 1–5/AB catalysts are well consistent, and thus indicate that 5/AB catalyst has the highest catalytic ability among TOT derivatives 1–5 (Fig. 3c).

ORR catalyst behaviors of 5

The ORR behavior of 5 was further investigated in terms of catalytic activity. The quantitative estimation of electron-transfer number (n) was conducted through Koutecky–Levich (K–L) plot46. Fig. 4a shows LSV curves of the 5/AB catalyst at various rotating speeds of the electrode (ω). The cathodic current increased at a high rotating speed, and j−1 and ω–1/2 are in a proportional relationship. An obtained value of n from the K-L plot was 2.4–2.7 in the range of 0.2–0.5 V, which was almost the same with those of AB blank and 1–4/AB catalysts (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), confirming the present oxygen reduction was occurred mainly through two-electron transferring process.

Electrochemical characterization of the 5/AB catalyst for ORR. a LSV curves of the 5/AB catalyst on an RDE with various rotating speeds. b K–L plots of the 5/AB obtained from (a). c, d RRDE voltammograms and the corresponding amperometric responses for ORR at the 5/AB catalyst (red line) and AB blank (dotted line). The electrode rotation rate was 1600 rpm, and the Pt ring electrode was 0.4 V vs. RHE. e, f HO2– production yields and n values of various catalysts derived from the disk and ring currents. Measurements were performed in an O2 saturated 0.1 M KOH aqueous solution at the scan rate of 5 mV s−1

The catalytic reduction of O2 was also examined at a rotating ring disk electrode (RRDE) under the same solution conditions. The disk potential was scanned from 1.0 to 0.2 V vs. RHE at a disk-rotation speed of 1600 rpm while holding the ring potential constant at 0.4 V. These data are shown in Fig. 4c–f for the 5/AB catalyst and AB blank. The anodic ring current (IR) increased at ~0.8 V vs. RHE which is close to EonORR, and the shape was similar to that of disk current (ID) throughout the measurement range. The n value and HO2− production yield were calculated as follows47:

where N = 0.43 is the collection efficiency of the ring electrode. The HO2− production yield upon the reduction of O2 was calculated as ca. 60% for 5/AB catalyst. The n value per O2 molecule at the 5/AB catalyst was calculated to be ca. 2.7, which is close to that obtained by the K-L plot in the range of 0.2–0.5 V (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results suggest that the pathway of ORR on the 5/AB catalyst is a two-electron process essentially, although the selectivity of the reaction was low. Similar behavior was observed for 1–4/AB catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 3). The origin of the large n and low H2O2 yield of TOT/AB catalysts as a two-electron process was not elucidated, and some experimental effect such as subsequent reaction would cause the low selectivity.

In order to optimize the 5/AB catalyst, we investigated the effect of mixing ratio of 5 and AB on catalytic activity. Both EonORR and current density became larger with increasing the amount of 5 up to 1:10 ratio, and then saturated at ~0.82 V (Fig. 5). The catalyst only containing 5 without AB showed little activity. This is because 5 is an insulator, and AB is necessary as a conductive additive to form electrical contact between 5 and electrode.

During repetition of the ORR process of 5/AB catalyst in 0.1 M KOH aqueous solution, both reduction current j and onset potential EonORR monotonously decreased at more than 20 cycles (Fig. 6a, b). As shown in the SEM images of surfaces of the 5/AB catalyst before and after the LSV measurement, the block-like crystals of 5 dispersed in AB became smaller after the reaction (Fig. 6c, d). Such a crystal decay caused by the redox reaction of 5 would be the origin of the degradation of ORR activity. However, the degradations were small, and the 5/AB catalyst exhibited a catalytic activity even after 100 cycles. Such a high stability of the ORR process of 5/AB catalyst would be derived from the thermodynamic stability of both neutral radical and monoanion of 5. Polymerization40 of the TOT skeleton and/or covalent attachment to carbon substrate29,30 would be effective for further improvement of the stability of ORR catalytic activity of 5.

Cycle performance of 5/AB catalyst. a LSV curves of 5/AB catalyst on an RDE in an O2 saturated 0.1 M KOH aqueous solution by repeatedly scanning the cell. b Plots of EonORR on cycles of LSV measurement. c, d SEM images of surface of 5/AB catalyst before and after LSV measurement, respectively. The scale bar for (c, d) represents 5 µm

Recently, it has been reported that trace levels (ppm) of transition metal impurities have a significant influence on the ORR catalytic activity48. In the case of 4 and 5, the contamination with Pd which was used in the synthesis as catalysts of cross-coupling reactions is expected to have effects on the ORR catalytic activity. Actually, in the case of a “crude” sample of 4 containing 3180 ppm of Pd impurity, the LSV curve shifted higher in ~0.03 V than that of Pd-free 4 (78 ppm of Pd impurity, smaller than the experimental error) (Supplementary Fig. 4). Following these results, the amounts of transition metal impurities of each TOT derivatives were measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis, and the ORR catalytic activities were measured only for samples of Pd impurities of <200 ppm (Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, in order to elucidate the effect of Pd contamination on the ORR catalytic activity, we demonstrated LSV measurements of the AB blank and 5/AB catalysts mixed with Pd/C (Fig. 7). Here, the mixing ratio of Pd was calculated based on the amount of 5 (AB:5 = 10:3) in the catalysts (Supplementary Table 2). The EonORR value became large gradually with increase of the Pd ratio, and EonORR of the catalyst including 100000 ppm (10%) Pd reached to ca. 0.90 V vs. RHE. We also conducted the LSV measurements of 5/AB catalysts in several batches including Pd impurities of 100–3000 ppm, however, an obvious relationship was not found between impurity and ORR catalytic activity (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results indicate that the effect of Pd impurity is negligible in the present experiments, since the amount of Pd impurity was smaller than 200 ppm for all TOT derivatives (Supplementary Table 1).

Substituent effect on ORR catalyst activity

The relationship between redox potentials in the solution state DPV measurement (Eox) and ORR potentials (EpORR and EonORR) of TOT/AB catalysts implies that a TOT derivative having an electron-donating group (4 and 5) has a higher catalytic activity. A close correlation between the redox potential and ORR catalytic activity has been also discussed in quinone analogues33. We conducted the density functional theory (DFT) calculation on 1−–5−, and their highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) energies were summarized in Table 1. Introduction of electron-donating phenyl and N-piperidinyl groups enhanced the HOMO energies of TOT monoanions from −1.38 eV of 1− to −1.23 eV of 4− and −1.15 eV of 5−, respectively. The obtained values correspond to EORR of the TOT derivatives, where 4 and 5 with higher HOMO energies showed higher ORR activities, whereas 1–3 with lower HOMO energies had low activities. In the ORR process, an electron moves from the catalyst to O2 (Fig. 1), and therefore the cooperation of redox of catalyst and O2 is necessary. As shown in the CV measurements of 4/AB catalyst (Fig. 3a) in a 0.1 M KOH aqueous solution, the oxidation peak of 4 (0.81 V) was close to the ORR peak potential (0.67 V) in comparison with those of 1–3/AB catalysts. Since the tails of the redox peak of 4 and the ORR peak overlapped each other, these processes could weakly cooperate, resulting in the slight shift of the EORR potential. In the case of 5/AB catalyst, the redox potential of 5 is expected to be lower than that of 4 from the Eox and DFT calculation. Although oxidation of 5− itself was not observed in both CV and LSV measurements, the redox of 5 and ORR processes would occur at the same or very close potential. These results indicate that the enhancement of the cooperativity of ORR and redox of TOT caused the highest activity in the 5/AB catalyst.

Reaction mechanism

Simply considering the reaction cycle shown in Fig. 1, the charge-transfer between TOT– and O2 generates HO2− and TOT neutral radical, which was electrochemically reduced at the electrode to generate TOT−, which further reduces O2. As shown in the HOMO distribution of 5− in the DFT calculation (Fig. 8), the largest HOMO coefficient locates at the central carbon atom, and this atom may also behave as a reactive site. On the other hand, in a recent study on the π-conjugated polymer-based ORR catalyst, it was discussed that the carbon atoms having positive charge densities adjacent to heteroatoms are the reactive sites to O240. Thus, we also investigated the charge density distribution on the TOT framework by the DFT calculation (Supplementary Table 3). All of 1−–5− have high positive charge densities of about +0.32 on the carbonyl carbon atoms (4, 8, 12-positions in Fig. 8). In addition, as the electron-donating ability of the substituent R increases, the charge densities at the 2, 6, and 10-positions shift positively, and the charge densities become +0.29 in 5− (Fig. 8). Therefore, it can be speculated that the positively charged carbon atoms behave as the reactive site in the ORR of 5/AB catalyst. As shown in Fig. 5a, the catalyst containing only 5 did not show a shift of EonORR and ORR catalytic activity. This result implies the AB works not only as a conductive additive, and that the electronic interaction between 5 and AB is necessary for the catalytic activity of 5/AB catalyst.

Discussion

It is difficult to simply compare the ORR catalytic activity of 5/AB with those of other catalysts such as heteroatom doped carbon6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18/graphene quantum dots34,35,36,37, because their electrode preparation methods, measurement conditions, and potential standard are different for each investigation. However, when these previous studies are overviewed as a whole, the EonORR values are ca. 0.80–0.85 V vs. RHE at most. We also compared the catalytic activity of 5 with quinone derivatives which are known to exhibit the two-electron ORR catalytic activity in the completely same conditions with those of TOT derivatives (Supplementary Fig. 6)29,30,31,32,33. The EonORR of the quinone derivatives were smaller than 0.80 V. Although EonORR of the 5/AB catalyst was smaller than that of Pt/C catalyst (1.13 V), the 5/AB catalyst possesses a similar or higher catalytic activity among these metal-free ORR catalysts.

In this paper, we have characterized the ORR catalytic activity of the TOT system, which gives stable neutral radical and monoanion. The screening of substituent groups on the TOT skeleton revealed that the N-piperidinyl derivative 5 exhibited a peculiarly high activity with a two-electron ORR process. The analysis of substituent effect on the redox potential and HOMO energy indicated that the cooperation of redox of TOT and ORR, both of which occurs at the same or close potential, is one of the most important factors of the catalytic activity. The high stability of both neutral radical and monoanion of TOT highly contributed to the stability of catalytic cycle over 100 times.

In the previously reported carbon-based ORR catalysts with heteroatom doping, top-down fabrication approach has been made, and the structures of the materials were not discrete and unclear. Therefore, it was difficult to discuss the mechanism of ORR process and the effect of chemical modification experimentally. The present study shows a molecular-level insight of the ORR catalytic activity on neutral radicals, and demonstrate a bottom-up approach for tailor-made designing for the metal-free ORR catalyst. Our next target is the four-electron ORR catalytic activity under acidic conditions that has not achieved in TOT-based catalysts, and the development of a high-performance metal-free fuel cell.

Methods

Materials

TOT neutral radicals 1–3 were synthesized according to our previous papers42,44. Solvents for the syntheses were dried (drying reagent in parenthesis) and distilled under an argon atmosphere prior to use: DMF (CaH2); THF (Na-benzophenone ketyl). Other commercially available materials were used as received. All reactions requiring anhydrous conditions were performed under an argon atmosphere.

Material characterization

Melting and decomposition points were measured with a hot-stage apparatus with a Yanako MP-J3, and were uncorrected. Melting and/or decomposition were detected by eye observation. The decomposition was observed by changing of the color, where the surface of powdered samples became dark above the decomposition points. Elemental analyses were performed at the Graduate School of Science, Osaka University. ICP-AES measurements were performed using an ICPS-8100 of Shimadzu Corporation, and amount of Fe and Cu impurities were also investigated. 1H NMR spectrum was obtained on a JEOL ECA-500 with DMSO-d6 using Me4Si as an internal standard. ESI-MS spectra were measured from solutions in MeOH on a Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap XL. Electronic spectra were measured for KBr pellets or solutions on a Shimadzu UV/vis scanning spectrophotometer UV-3100PC. Infrared spectrum was recorded on a JASCO FT/IR-660 Plus spectrometer using a KBr plate (resolution 4 cm−1).

Synthesis of 4

In a 300-mL Schlenk flask, radical precursor 3 (422 mg, 0.75 mmol), phenyl boronic acid (932 mg, 7.64 mmol), Pd(PPh3)4 (91.2 mg, 0.079 mmol) were suspended in a mixture of DMF (50 mL) and 1 M NaHCO3 aqueous solution (50 mL). The mixture was degassed by a repeated pump-thaw method, and was stirred at 100 °C for 17 h. After cooled to room temperature, 2 M HCl aqueous solution (50 mL) was poured into the reaction mixture. The resulting precipitate was collected, and then washed with EtOH and ethyl acetate. To a suspension of the resulting solid in a 100-mL round-bottomed flask, acetone (50 mL) and (n-Bu)4NOH (1 M MeOH solution, 1.0 mL, 1.0 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 1 h, and then the evaporated under reduced pressure. The residual was washed with hot water, and the precipitate was collected by filtration. The resulting powder was recrystallized from EtOH, to give the (n-Bu)4N+ salt of 4− (496 mg, 83%) as a green powder. mp. 255–259 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.93 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 12 H), 1.26–1.34 (m, 8 H), 1.52–1.62 (m, 8 H), 3.13–3.17 (m, 8 H), 7.43 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3 H), 7.58 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 6 H), 7.90 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 6 H), 9.04 (s, 6 H); IR (KBr) ν 3054, 3030, 2957, 2872, 1611, 1541, 1510, 1484, 1281 cm−1; UV (CH2Cl2) λmax (ε) 282 (7.1 × 104), 346 (2.7 × 104), 414 (5.1 × 104), 640 (1.4 × 104), 680 (2.0 × 104) nm; UV (KBr) λmax 266, 356, 422, 684 nm; ESI-MS (negative-mode) m/z 549 (M– – (n-Bu)4N); Anal. Calcd for C56H57N1O3: C, 84.92; H, 7.25; N, 1.77%. Found: C, 84.68; H, 7.22; N. 1.83%.

In a 50-mL Schlenk flask, (n-Bu)4N+ salt of 4− (40.4 mg, 0.051 mmol) was dissolved in THF (10 mL). To this mixture, a solution of DDQ (39.3 mg, 0.173 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was added using cannula. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 0.5 h. The resulting precipitate was collected by filtration, and then washed with THF, to give 4 (27.4 mg, 98%) as a green powder. dp. > 300 °C; IR (KBr) 3085, 1634, 1577, 1366, 1327 cm−1; UV (KBr) λmax 268, 338, 702, 1306, 1580(sh) nm; Anal. Calcd for (C40H21O3)(H2O)0.4: C, 86.28; H, 3.95%. Found: C, 86.31; H, 4.01%.

Synthesis of 5

In a pressure tube, (n-Bu)4N+ salt of 3− (2.00 g, 2.48 mmol), piperidine (3.0 mL, 5.4 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (220 mg, 0.26 mmol), XPhos (120 mg, 0.26 mmol), and t-BuONa (1.08 g, 11.8 mmol) were dissolved in THF (100 mL). The mixture was degassed by a repeated pump-thaw method, and then the tube was sealed. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 18 h. After cooled to room temperature, MeOH and CHCl3 was added to dissolve the product. The insoluble material was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was subjected to a silica gel column chromatography with mixtures of 1:4 benzene/CHCl3 containing 0.5% MeOH–9:1 CHCl3/MeOH as eluant to give 5 (351 mg, 25%) as a green powder. Further purification to remove Pd impurities contained in a very small amount, the product was treated with metal scavenger R-cat-Sil AP (Kanto Chemical co.inc.) in CHCl3 for 8 h. The metal scavenger was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was washed with hexane, and then recrystallized from hot CHCl3, to give 5 for the ORR measurement. Since 5− was oxidized by air during the purification, neutral radical of 5 was isolated. dp.> 300 °C; IR (KBr) ν 2930, 2851, 1623, 1577, 1394 cm−1; UV (CHCl3) λmax (ε) 274 (5.5 × 104), 810 (1.2 × 104), 982 (1.2 × 104) nm; UV (KBr) λmax 266, 366, 660(sh), 836, 1625 nm; Anal. Calcd for (C37H31N3O3)(H2O): C, 75.49; H, 6.51; N, 7.14%. Found: C, 75.82; H, 6.52; N, 6.84%. All ORR catalytic measurements of the 5/AB catalysts were demonstrated the sample prepared in the procedure (batch 6 in Supplementary Fig. 5, Pd impurity 78 ppm).

Solution state electrochemical measurements

Cyclic voltammetry measurement was made with an ALS Electrochemical Analyzer model 630A. Cyclic voltammogram was recorded with 3-mm-diameter carbon plate and Pt wire counter electrodes in dry DMF containing 0.1 M n-Bu4NClO4 as supporting electrolyte at room temperature. The experiment employed a Ag/AgNO3 reference electrode, and the final result was calibrated with Fc/Fc+ couple.

ORR characterization

ORR measurement was made with a dual electrochemical analyzer ALS730EM with rotating disk electrode (RDE) or rotating ring disk electrode (RRDE-3A). The catalyst ink for the electrochemical measurement was prepared as follows. Firstly, ink solvent was prepared by mixing 1 mL of 5 wt.% Nafion solution (Aldrich, 527084), 4.79 mL of pure water and 5.11 mL of isopropyl alcohol (Wako, 166–04831). Then, TOT-added ink was prepared by dispersing 0.3 mg of TOT neutral radical and 1 mg of acetylene black (AB) into 80 μL of the ink solvent. Pt/C-added ink was prepared by dispersing 0.65 mg of 46.1 % Pt/C into 80 μL of the ink solvent. Electrochemical activities were examined through CV and LSV studies using 0.1 M KOH solution at room temperature as the electrolyte solution, a rotating disk electrode (glassy carbon disk) as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference electrode and a Pt wire electrode as the counter electrode. The catalyst ink was loaded on the glassy carbon disk at a 160 μg–TOT/cm2, 160 μg–Pt/cm2, 530 μg–AB/cm2 and 180 μg–Nafion/cm2. The electrode rotation speed was 1600 rpm for LSV measurement, and the scanning rate was 5 mV/s for LSV and CV measurements.

Purchased catalysts were as follows: 46.1 % Pt/C (Tanaka Kikinzoku, TEC10E50E), acetylene black (AB; Denka), 9,10-phenanthrenequinone (Aldrich, 156507), 9,10-anthraquinone (TCI, A0502) and 2-amino-9,10-anthraquinone (TCI, A0255). These were used without further purification.

Computational details

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Gaussian 09 program package. The calculation was performed at the B3LYP/6–31G** level of theory with optimization of the geometries.

Data availability

The other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Cheng, F. & Chen, J. Metal-air batteries: from oxygen reduction electrochemistry to cathode catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2172–2192 (2012).

Dai, L., Xue, Y., Qu, L., Choi, H.-J. & Baek, J.-B. Metal-free catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Rev. 115, 4823–4892 (2015).

Banham, D. et al. A review of the stability and durability of non-precious metal catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 285, 334–348 (2015).

Lefèvre, M., Proietti, E., Jaouen, F. & Dodelet, J.-P. Iron-based catalysts with improved oxygen reduction activity in polymer electrolyte fuel cells. Science 324, 71–74 (2009).

Wu, G., More, K. L., Johnston, C. M. & Zelenay, P. High-performance electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction derived from aniline, iron, and cobalt. Science 332, 443–447 (2011).

Gong, K., Du, F., Xia, Z., Durstock, M. & Dai, L. Nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube arrays with high electrocatalytic activity for oxygen reduction. Science 323, 760–764 (2009).

Hu, C. & Dai, L. Carbon-based metal-free catalysts for electrocatalysis beyond the ORR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 11736–11758 (2016).

Yang, L. et al. Boron-doped carbon nanotubes as metal-free electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7132–7135 (2011).

Yu, D., Zhang, Q. & Dai, L. Highly efficient metal-free growth of nitrogen-doped single-walled carbon nanotubes on plasma-etched substrates for oxygen reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 15127–15129 (2010).

Rao, C. V., Cabrera, C. R. & Ishikawa, Y. In search of the active site in nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube electrodes for the oxygen reduction reaction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 2622–2627 (2010).

Yasuda, S., Yu, L., Kim, J. & Murakoshi, K. Selective nitrogen doping in graphene for oxygen reduction reactions. Chem. Commun. 49, 9627–9629 (2013).

Liu, R., Wu, D., Feng, X. & Müllen, K. Nitrogen doped ordered mesoporous graphitic arrays with high electrocatalytic activity for oxygen reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 2565–2569 (2010).

Lu, Z.-J. et al. Nitrogen-doped reduced-graphene oxide as an efficient metal-free electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction in fuel cells. RSC Adv. 3, 3990–3995 (2012).

Liu, Z. W. et al. Phosphorus-doped graphite layers with high electrocatalytic activity for the O2 reduction in an alkaline medium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 3257–3261 (2011).

Ozaki, J., Kimura, N., Anahara, T. & Oya, A. Preparation and oxygen reduction activity of BN-doped carbons. Carbon 45, 1847–1853 (2007).

Ikeda, T. et al. Carbon alloy catalysts: active sites for oxygen reduction reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C. 112, 14706–14709 (2008).

Niwa, H. et al. X-ray absorption analysis of nitrogen contribution to oxygen reduction reaction in carbon alloy cathode catalysts for polymer electrolyte fuel cells. J. Power Sources 187, 93–97 (2009).

Ozaki, J., Tanifuji, S., Furuichi, A. & Yabutsuka, K. Enhancement of oxygen reduction activity of nanoshell carbons by introducing nitrogen atoms from metal phthalocyanines. Electrochim. Acta 55, 1864–1871 (2010).

Zhang, L. & Xia, Z. Mechanisms of oxygen reduction reaction on nitrogen-doped graphene for fuel cells. J. Phys. Chem. C. 115, 11170–11176 (2011).

Guo, D. et al. Active sites of nitrogen-doped carbon materials for oxygen reduction reaction clarified using model catalysts. Science 351, 361–365 (2016).

Jasinski, R. A new fuel cell cathode catalyst. Nature 201, 1212–1213 (1964).

Zagal, J. H. & Koper, M. T. M. Reactivity descriptors for the activity of molecular MN4 catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 14510–14521 (2016).

Ren, C. et al. Electrocatalytic study of a 1,10-phenanthroline–cobalt(II) metal complex catalyst supported on reduced graphene oxide towards oxygen reduction reaction. RSC Adv. 6, 33302–33307 (2016).

Zhang, W., Lai, W. & Cao, R. Energy-related small molecule activation reactions: oxygen reduction and hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions catalyzed by porphyrin- and corrole-based systems. Chem. Rev. 117, 3717–3797 (2017).

Pegis, M. L., Wise, C. F., Martin, D. J. & Mayer, J. M. Oxygen reduction by homogeneous molecular catalysts and electrocatalysts. Chem. Rev. 118, 2340–2391 (2018).

Andrieux, C. P., Hapiot, P. & Saveánt, J.-M. Electron transfer coupling of diffusional pathways. Homogeneous redox catalysis of dioxygen reduction by the methylviologen cation radical in acidic dimethylsulfoxide. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 189, 121–133 (1985).

Mase, K., Ohkubo, K., Xue, Z., Yamada, H. & Fukuzumi, S. Catalytic two-electron reduction of dioxygen catalysed by metal-free [14]triphyrin(2.1.1). Chem. Sci. 6, 6496–6504 (2015).

Campos-Martin, J. M., Blanco-Brieva, G. & Fierro, J. L. G. Hydrogen peroxide synthesis: An outlook beyond the anthraquinone process. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 45, 6962–6984 (2006).

Vaik, K., Sarapuu, A., Tammeveski, K., Mirkhalaf, F. & Schiffrin, D. J. Oxygen reduction on phenanthrenequinone-modified glassy carbon electrodes in 0.1 M KOH. J. Electroanal. Chem. 564, 159–166 (2004).

Tammeveski, K., Kontturi, K., Nichols, R. J., Potter, R. J. & Schiffrin, D. J. Surface redox catalysis for O2 reduction on quinone-modified glassy carbon electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 515, 101–112 (2001).

Li, Q., Zhang, S., Dai, L. & Li, L. Nitrogen-doped colloidal graphene quantum dots and their size-dependent electrocatalytic activity for the oxygen reduction reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18932–18935 (2012).

Golabi, S. M. & Raoof, J. B. Catalysis of dioxygen reduction to hydrogen peroxide at the surface of carbon paste electrodes modified by 1,4-naphthoquinone and some of its derivatives. J. Electroanal. Chem. 416, 75–82 (1996).

Sarapuu, A., Helstein, K., Vaik, K., Schiffrin, D. J. & Tammeveski, K. Electrocatalysis of oxygen reduction by quinones adsorbed on highly oriented pyrolytic graphite electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 55, 6376–6382 (2010).

Šljukić, B., Banks, C. E., Mentus, S. & Compton, R. G. Modification of carbon electrodes for oxygen reduction and hydrogen peroxide formation: the search for stable and efficient sonoelectrocatalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 992–997 (2004).

Li, Q. et al. Electrocatalytic oxygen activation by carbanion intermediates of nitrogen-doped graphitic carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 3358–3361 (2014).

Fukushima, T., Drisdell, W., Yano, J. & Surendranath, Y. Graphite-conjugated pyrazines as molecularly tunable heterogeneous electrocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10926–10929 (2015).

Ricke, N. D. et al. Molecular-level insights into oxygen reduction catalysis by graphite-conjugated active sites. ACS Catal. 7, 7680–7687 (2017).

Lyth, S. M. et al. Carbon nitride as a nonprecious catalyst for electrochemical oxygen reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 20148–20151 (2009).

Khomenko, V. G., Barsukov, V. Z. & Katashinskii, A. S. The catalytic activity of conducting polymers toward oxygen reduction. Electrochim. Acta 50, 1675–1683 (2005).

Patnaik, S. G., Vedarajan, R. & Matsumi, N. BIAN based electroactive polymer with defined active centers as metal-free electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) in aqueous and nonaqueous media. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1, 1183–1190 (2018).

Morita, Y., Suzuki, S., Sato, K. & Takui, T. Synthetic organic spin chemistry for structurally well-defined open-shell graphene fragments. Nat. Chem. 3, 197–204 (2011).

Morita, Y. et al. Organic tailored batteries materials using stable open-shell molecules with degenerate frontier orbitals. Nat. Mater. 10, 947–951 (2011).

Ikabata, Y. et al. Near-infrared absorption of π-stacking columns composed of trioxotriangulene neutral radicals. npj Quantum Mater. 2, 27 (2017).

Morita, Y. et al. Trioxotriangulene: air- and thermally stable organic polycyclic carbon-centered neutral π-radical without steric protection. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 91, 922–931 (2018).

Murata, T., Yamada, C., Furukawa, K. & Morita, Y. Mixed-valence salts based on carbon-centered neutral radical crystals. Commun. Chem. 1, 47 (2018).

Bard, A. J. & Faulkner, L. R. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications 2nd edn. (Wiley-VCH, New York, 2001).

Xing, X., Yin, G. & Zhang, J. Rotating Electrode Methods and Oxygen Reduction Electrocatalysts 1st edn. (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2014).

Wang, L., Ambrosi, A. & Pumera, M. “Metal-free” catalytic oxygen reduction reaction on heteroatom-doped graphene is caused by trace metal impurities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 13818–13821 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Preparation and purification of neutral radical 5 suitable for ORR measurements were done by Dr. Kaori Fujisawa (Aichi Institute of Technology). We thank Dr. Tsutomu Ioroi (Department of Energy and Environment, The National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST)) for fruitful discussion on the ORR catalytic analyses. We would like to thank the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) Program ‘Creation of Innovative Functions of Intelligent Materials on the Basis of the Element Strategy’ of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M. planned this project. T.M., H.M. and Y.M. prepared the materials and demonstrated spectroscopic analyses. K.K. and R.T. carried out the measurement of electrocatalyst activities for ORR. All authors wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murata, T., Kotsuki, K., Murayama, H. et al. Metal-free electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction based on trioxotriangulene. Commun Chem 2, 46 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0149-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0149-9

This article is cited by

-

Metal oxide stabilized zirconia modified bio-derived carbon nanosheets as efficient electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction

Journal of Applied Electrochemistry (2024)

-

N-piperidinyl substituted trioxotriangulene as an efficient catalyst for oxygen reduction reaction in fuel cell application—a DFT study

Ionics (2023)

-

MOF/PCP-based Electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.