Abstract

Minimizing the use of precious metal remains a challenge in heterogeneous catalysis, such as platinum-based catalysts for formaldehyde oxidation. Here we report the catalyst system Pt/TiO2 with low platinum loading of 0.08 wt%, orders of magnitude lower than conventional catalysts. A volcano-like relationship is identified between reaction rates of formaldehyde and platinum sizes in a scale of single-atoms, nanoclusters and nanoparticles, respectively. Various characterization techniques demonstrate that platinum nanoclusters facilitate more activation of O2 and easier adsorption of HCHO as formates. The activated O facilitates the decomposition of formates to CO2 via a lower reaction barrier. Consequently, this size platinum with such low loading realizes complete elimination of formaldehyde at ambient conditions, outperforming single-atoms and nanoparticles. Moreover, the platinum nanoclusters exhibit a good versatility regardless of supporting on “active” FeOx or “inert” Al2O3 for formaldehyde removal. The identification of the most active species has broad implications to design cost-effective metal catalysts with relatively lower loadings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Precious metal-based catalysts have been widely used in many industrial processes of energy and environmental catalysis1,2,3. Nevertheless, due to the high cost and the scarcity in earth reserves of noble metals, lower metal loading is strongly desired for a supported catalyst. The increase of atomic efficiency via higher dispersion of metal species gives a promising strategy3,4. Particularly, with the development of catalyst preparation methods and characterization techniques, the concept of single-atom metal catalyst has been successfully proposed and the recognition of the inherent reactivity sites has been deepened into single-atom scale5,6,7. It is generally accepted that the metal species as single-atoms exhibit the highest atomic efficiency than other size scale4,8,9, which presents a great potential to reduce the high cost of noble-metal catalysts.

However, in recent reports, ensembles of metal atoms with specific geometric constructions are frequently found as active sites with higher performance than single-atoms. For example, the Pt2 dimers on graphene via atomic layer deposition method possessed ~17 times higher specific rate than Pt single-atoms in hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane10. The Rh ensembles with ~0.9 nm size presented much higher performance than Rh single-atoms in the oxidation of propane and propene11. The variation of metal sites alternative to single-atoms can result in striking difference of interaction strength with the adsorbates. It was shown that Pt single-atoms owned stronger adsorption of CO than Pt particles, which led to the retention of the related adsorption peak by infrared studies and lower activity for CO oxidation and water gas shift12. The nature of active sites as single-atoms, clusters, and nanoparticles can even affect the reaction mechanisms13,14,15,16, whereas the inconsistencies about the identification of uniform active metal species still exist. Moreover, the mixture of metal particle sizes in a conventional catalyst usually results in lower metal utilization efficiency because only the species with specific size play the dominant role on catalytic performance while others are rather wasted. Thus, to obtain the precious metal catalyst with specific dispersion is imperative, which is helpful to minimize the metal content by unravelling the most efficient species.

Pt-based catalysts attract significant attention due to their remarkable abatement capacities for room-temperature removal of formaldehyde (HCHO), which has been regarded as one of the most efficient methods to transform pollutants into harmless CO2 and H2O with low energy consumption17,18. He et al. earlier detected TiO2 supported Pt metals for the oxidation of HCHO and suggested that the supported single-atoms played as active centers19,20, while others claimed nanoparticles with ~3 nm or even larger size were more favorable21,22. In general, to ensure complete HCHO elimination at room temperature, typically high Pt content (≥1%) is often employed. Moreover, a clear distinction of optimal Pt size range in this reaction has not been unified and how the particle size exerts influence on the activity is still not well addressed.

Here we show a series of Pt/TiO2 catalysts using Pt species with specific size as precursor and compare them with Pt single-atom and Pt nanoparticle catalysts. As the traditional impregnation or deposition-precipitation (DP) method usually result in the coexistence of multiple forms of species with various sizes23,24,25, our approach is atom economical. It is found that the Pt nanoclusters with size of ~1 nm on high surface area of anatase TiO2 and with loading of only 0.08 wt%, orders of magnitude lower than previous Pt-based catalysts, can realize complete oxidation of HCHO in high concentration and wide humidity conditions. The size-dependent effect is then unraveled by the establishment of relationship between adsorption and reaction performance, which affords an explicit understanding of the importance of Pt nanoclusters. Furthermore, the versatility of ultra-low loading Pt nanoclusters in the elimination of HCHO is confirmed by extending supports to either “active” FeOx or “inert” Al2O3.

Results

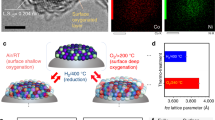

Preparation of Pt/TiO2 catalysts

The Pt/TiO2 catalysts with specific Pt size were tailor-made using Pt colloids as precursors synthesized by alkaline ethylene glycol (EG) reduction26,27 and then deposited on TiO2 via colloidal deposition method13,28. To prepare the catalysts with single-atom or/and subnano dispersion, the conventional DP method was employed as reported previously24,29. The details on sample preparation were provided in the methods and the schematic about catalyst design was described in Fig. 1. In addition, the support of high surface area TiO2 was obtained by the hydrolysis of tetrabutyl titanate (TTBT)30. The resulted Pt/TiO2 samples were denoted as nPt-x with n as loading amount determined by ICP results and x as particle size, such as 0.08 Pt-NC for catalyst with Pt size of ~1 nm, 0.09 Pt-NP with Pt size of ~2 nm, 0.01 Pt-SAC for single-atom catalyst and 0.06 Pt-Mix for mixed dispersion catalyst including single-atoms and subnanoclusters.

Catalyst structure

The physiochemical properties of the catalysts were summarized in Supplementary Table 1. As seen, the support of high surface area TiO2 was successfully synthesized, of which the BET surface area is as high as 145 m2 g−1 and similar surface areas are found after supporting the Pt species. The XRD patterns of TiO2 and supported Pt catalysts were presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. All the samples show typical anatase patterns (JCPDS No. 04–0477) with size around 12 nm, which is also confirmed by HRTEM results in Supplementary Fig. 2 that there are lattice fringes with spacings of 0.353 and 0.347 nm for the (101) plane of anatase TiO2. In addition, there are no any Pt characteristic peaks, which results from high dispersion of Pt species or ultra-low loadings.

To obtain the size distributions of Pt species, the HAADF-STEM technology was used to visually observe the Pt dispersion of these catalysts. Figure 2 shows the representative images of four nPt-x samples and more images are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. As seen, the Pt/TiO2 with loading of 0.01 wt% by DP method presents the dominant single-atoms (denoted as 0.01 Pt-SAC) due to the extremely low loading and the reduction of short-/long-range Pt-Pt interactions. As anticipated, with the rise of loading amount to 0.06%, there are Pt subnanometer clusters due to the aggregation of single-atoms (denoted as 0.06 Pt-Mix). Statistical analysis (obtained by counting around 200 particles in AC-HAADF-STEM images) shows the average size of around 0.5 nm for 0.06 Pt-Mix with the distribution frequencies: 24% single-atoms, 44% clusters of 0.2–0.5 nm, and 32% clusters of 0.5–0.8 nm. It indicates that the traditionally DP method is not proper to obtain Pt/TiO2 catalyst with specific size and higher-loading Pt can lead to wide size distribution, which is in accordance with many studies23,24,25. In contrast, we can find that the precursor of Pt colloid prepared by EG reduction exhibits a homogeneous size as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. By changing preparation parameters of Pt colloid and loadings on the support of TiO2, the Pt nanoclusters with mean diameter of 1.1 nm were obtained denoted as 0.08 Pt-NC and the nanoparticles with 2.1 nm denoted as 0.09 Pt-NP. It was claimed previously that the colloidal method did not result in the existence of metal species as single-atoms or bi-layer clusters31. These results indicate that we have successfully synthesized TiO2 supported Pt catalysts with rather uniform size from single-atoms, nanoclusters to nanoparticles, as described in Fig. 1, which can be used as models to detect the size-dependent effect in HCHO oxidation.

Representative HAADF-STEM images of the Pt/TiO2 catalysts. a 0.01 Pt-SAC, b 0.06 Pt-Mix, c 0.08 Pt-NC, and d 0.09 Pt-NP. The Pt species are highly dispersed as single-atoms (white circles) on 0.01 Pt-SAC, single-atoms and clusters on 0.06 Pt-Mix, ~1 nm on 0.08 Pt-NC, and ~2 nm on 0.09 Pt-NP, respectively. a Scale bars 2 nm. b–d Scale bars 10 nm

Catalytic performance for HCHO oxidation

Figure 3a illustrates the profile of HCHO conversions as a function of reaction temperatures over TiO2 and Pt/TiO2 catalysts with various size scales. The pure TiO2 shows no conversion of HCHO in the temperature range of 20–80 °C. After loading 0.08 wt% Pt nanoclusters, the conversion of HCHO reaches 100% at 20 °C. It is the first time that Pt-based catalyst with such low loading exhibits so good performance in high concentration of raw HCHO. As listed in Table 1, the T100 value is much lower on 0.08 Pt-NC than on most of Pt-based catalysts. Inversely, the performance of HCHO oxidation is declined with the further increase of Pt size on 0.09 Pt-NP, which shows conversion of ~82% at 20 °C and ~100% at 60 °C. Moreover, on Pt-Mix with approximately loading of 0.06 wt%, the HCHO conversion is dramatically decreased to 17% at 20 °C and on 0.01 Pt-SAC the activity is extremely low with conversion of only ~5% even at 80 °C. During the catalyst preparation, there are Na ions residual on the resultant catalysts due to the use of NaOH, which can enhance the activity of HCHO oxidation on noble-metal based catalysts via promoting the metal dispersions or altering the electronic state of metal species20,32,33. As listed in Supplementary Table 1, the amounts of Na are all low with 0.003 wt% on Pt-NC, 0.004 wt% on Pt-NP and 0.08 wt% on Pt-Mix, respectively. However, the ~1 nm Pt nanoclusters possess higher removal efficiency than both nanoparticles and single-atoms. These results indicate that the particle size effect of Pt species on HCHO conversion is more pronounced than the effect of Na ions. To confirm the role of Pt nanocluster species, we also prepared Pt-NC catalysts with loadings of 0.01 and 0.05 wt%, respectively. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, the overall conversion profiles are upshifted to higher level on these two samples compared with 0.01 Pt-SAC and 0.06 Pt-Mix, in which the conversions are ~13% and ~71% on 0.01 Pt-NC and 0.05Pt-NC at 20 °C, respectively. All these results indicate that the particle size of Pt species affects the performance for low-temperature oxidation of HCHO and the ~1 nm Pt nanocluster species present the best.

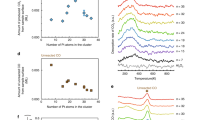

Performance of various Pt/TiO2 catalysts for HCHO oxidation. a HCHO conversions as a function of reaction temperatures on the Pt/TiO2 catalysts with various size scales. Reaction condition: 160 ppm HCHO, 20 vol% O2, and balance He, RH (relative humidity): 50%, WHSV (weight hourly space velocity): 30,000 mL h−1 gcat−1. b Specific reaction rates of HCHO at 30 °C and the mean size of Pt species on these Pt/TiO2 catalysts. The Pt size ranges with the error bars were obtained from Fig. 2

To show the intrinsic activity of these Pt/TiO2 catalysts, the specific rates and TOF values in HCHO oxidation were compared by measurement at 30 °C. As shown in Table 1, 0.08 Pt-NC gives a maximum value as high as 332.7 mmol gPt−1 h−1, which is almost 2.4 times higher than that of 0.09 Pt-NP (136.5 mmol gPt−1 h−1), 5.8 times higher than that of 0.06 Pt-Mix (57.1 mmol gPt−1 h−1) and 36.6 times higher than that of 0.01 Pt-SAC (9.1 mmol gPt−1 h−1). With comparisons in terms of TOF values, it is around twice higher on 0.08 Pt-NC than on 0.09 Pt-NP and around one order of magnitude higher than 0.06 Pt-Mix. As for the relationship between performance and Pt size scale, an obvious volcano-like profile exists with the best performance on the Pt species with size of ~1 nm as shown in Fig. 3b. When compared with typically reported Pt-based catalysts in literatures34,35,36,37,38,39,40, our 0.08 Pt-NC is times or orders of magnitude more active. Unambiguously, the Pt/TiO2 catalyst with nanocluster dispersion and ultra-low loading of 0.08 wt% possesses an unprecedentedly remarkable activity for HCHO oxidation at room temperature either in the removal efficiency of HCHO or in the specific reaction rate.

As for the application in the decorative material manufacturing, the tolerance of 0.08 Pt-NC to higher HCHO concentrations is necessarily investigated. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, under level of 390 ppm HCHO, it can still be totally eliminated at 30 °C with good stability as well. With further increase of HCHO concentration, the conversion keeps a constant value despite of a gradual decrease to 92% at 720 ppm and 86% at 1300 ppm. That is, the Pt nanocluster catalyst still displays a remarkable HCHO elimination capacity to higher concentration of raw HCHO. On the other hand, this catalyst should be subjected to more rigor circumstance, since the humidity varies with the climates or other factors by air conditioning. It is also imperative to explore the influence of moisture in a wide range of relative humidity. As shown in Fig. 4, either in the dry condition or at a high relative humidity of 75%, 0.08 Pt-NC yields a total conversion of HCHO. Moreover, no deactivation takes place during the long working period of 1200 min, which implies that this catalyst can tolerate harsh conditions from dry to highly moist air. Through modulating various working circumstance, our Pt nanocluster catalyst still displays an extremely high HCHO removal efficiency and good stability, further demonstrating the significantly adaptive capacity and the high potential in practical application.

The adsorption and activation of HCHO and O2

The above results showed that the catalyst with ~1 nm Pt nanoclusters presented the highest activity in HCHO removal, which totally eliminated HCHO with ultra-low loading of 0.08 wt% at ambient temperature, outperforming Pt in single-atom configuration and in larger nanoparticle scale. The adsorption of HCHO and O2 on these Pt catalysts was then investigated to unravel the factors for the high performance of 0.08 Pt-NC.

As displayed in Fig. 5a, many complex peaks appear after the introduction of HCHO at room temperature by DRIFTS test, which are attributed to formates, (bi-) carbonates, dioxymethylene (DOM), respectively41,42, as listed in Supplementary Table 2. Correspondingly, the OH species located at 3671 cm−1, which is confirmed by O1s XPS results in Supplementary Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 1, gradually decrease with the time on 0.08 Pt-NC as shown detailedly in Supplementary Fig. 8, indicating the quick transformation of HCHO due to the reaction with OH species. However, the Pt species with different size can affect the distributions of these intermediates. As seen from Fig. 5b, the ratios of formates, (bi-) carbonates, and DOM are different as quantified from the IR areas: the formates are dominant on 0.08 Pt-NC while that is DOM on 0.06 Pt-Mix, suggesting higher oxidation ability of OH species on Pt-NC as DOM can be considered as a kind of intermediate to form formates43. Therefore, the formates which are produced by the reaction of HCHO and OH species are more easily generated on the Pt-NC catalyst than on the Pt-NP or Pt-Mix catalyst.

The activation of O2 is important for many oxidation reactions on supported metal catalysts44,45,46. As shown in the microcalorimetric results of O2 adsorption in Fig. 6, the adsorption heats of O2 on 0.06 Pt-Mix, 0.08 Pt-NC and 0.09 Pt-NP are all around 350 kJ mol−1, Fig. 6a, which is close to that on the metallic Pt species47, implying the dissociative adsorption of O2 to atomic O. These results suggest the Pt species as the main sites for the activation of O2. However, 0.08 Pt-NC owns the highest uptake of O2 (3.2 μmol gcat−1), which is 1.3 times of that on 0.09 Pt-NP (2.4 μmol gcat−1) and 16 times of 0.06 Pt-Mix (0.2 μmol gcat−1), respectively, Fig. 6b. It probably resulted from the presence of most metallic Pt species on 0.08 Pt-NC (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 7b), which is mainly due to the preparation method using Pt colloid as precursor26. The activated O atoms were suggested to be favorable for the oxidation of HCHO to CO2 by promoting the transformation of HCHO into formates35,42. Thus, the high capacity of O2 activation on 0.08 Pt-NC facilitates the oxidation of HCHO at room temperature.

Reaction behaviors during HCHO oxidation

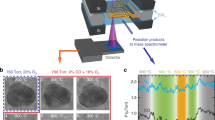

To prove higher oxidation ability of Pt-NC due to the role of activated O or OH species, in situ DRIFTS tests were performed. As shown in Fig. 7, after the introduction of O2 and H2O, the formates with special C–H and COO* peaks dramatically decrease on all the three samples with the increase of OH species. It should be noted that the C–H peaks decrease and disappear in 10 min on Pt-NC as shown in Fig. 7b (red box) while they still exist at 20 min on Pt-Mix and Pt-NP as displayed in Fig. 7a–c (red box). These phenomena indicate that the Pt-NC catalyst present the highest transformation rate of formates, which facilitates the higher performance corresponding to the results in Fig. 3. From the detailed peak evolution, the amount of carbonates and bicarbonates remains unchanged on the 0.08 Pt-NC catalyst while on Pt-Mix and Pt-NP catalysts, the carbonates and bicarbonates are gradually accumulated with time and finally become more dominant as seen in Fig. 7d. It has been suggested that the deep oxidation of formates originated from the higher oxidation ability of oxygen species that activated on metallic Pt species35,48. Thus, 0.08 Pt-NC promotes the production of CO2 and contrastively, more carbonates and bicarbonates are generated on both 0.09 Pt-NP and 0.06 Pt-Mix. Further, the temperature-programmed surface reaction (TPSR) experiments in Supplementary Fig. 9 show that the temperature of CO2 release is around ~30 °C on 0.08 Pt-NC, lower than that on both 0.09 Pt-NP and 0.06 Pt-Mix. The activation energies for the reaction of HCHO with O2 + H2O were then tested. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 10, it is the lowest of around 16 kJ mol−1 on 0.08 Pt-NC while higher of 19 kJ mol−1 on 0.09 Pt-NP and 21 kJ mol−1 on 0.06 Pt-Mix. Coupled with the results of Fig. 7, the lower activation energy on 0.08 Pt-NC correlates well with the deep reaction between formates and OH species to produce CO2.

Reaction behaviors during HCHO oxidation by in situ DRIFTS. The spectra were obtained after introducing O2 + H2O onto the samples preadsorbed with HCHO. a 0.06 Pt-Mix, b 0.08 Pt-NC, and c 0.09 Pt-NP, respectively, and d the spectra at steady state. The red box in Fig. 7a–c shows the change of C-H bond in formates with time

Since the Pt nanocluster species are of significance, it should confirm whether these species with such low loading work well when supporting on different types of oxides49,50. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, with support of either “active” FeOx or “inert” Al2O3, the mean size of Pt species is still around 1 nm despite of slightly different distribution percentages. These Pt-NC catalysts still exhibit prominent performance in HCHO oxidation at low temperatures as shown in Fig. 8a. The HCHO conversions are all higher than 95% at 20 °C on Pt-NC/Al2O3 and Pt-NC/FeOx with analogously low loadings of ~0.1 wt% while they can be negligible on single Al2O3 and FeOx support. Moreover, similar activation energies of ~15 kJ mol−1 are obtained on these Pt nanoclusters regardless of supporting on Al2O3, FeOx, and TiO2 as shown in Fig. 8b and Supplementary Fig. 10, although some differences exist in the reaction rates probably due to the support sites for the formation of some formate intermediates or on the influence of size distribution of Pt species51,52. These results unequivocally confirm that the ~1 nm Pt nanoclusters are responsible for the big raise in the activity of Pt-NC catalysts with ultra-low metal loadings for low-temperature HCHO removal.

Versatility of Pt nanoclusters on various oxides for HCHO oxidation. a HCHO conversions as a function of reaction temperature over Pt nanocluster species supported on “active” FeOx (0.07Pt-NC/FeOx) or “inert” Al2O3 (0.13Pt-NC/Al2O3). b Arrhenius plots of reaction rates versus 1/T for HCHO conversion on these catalysts. Reaction conditions: 160 ppm HCHO, 20 vol% O2, He balance, RH (relative humidity): 50%

Discussion

Pt-based catalysts were extensively studied and considered to be the most effective for the oxidation of HCHO at room temperature19,53,54. One of the limits for their industrial application is caused by the expensive cost with Pt loading of usually ≥1 wt% despite of using various supports18,55. In this work, we synthesized a high surface area TiO2 supported Pt catalyst with loading of only 0.08 wt%, which can realize total elimination of HCHO in high concentration and wide relative humidity. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first report that Pt-based catalyst with such low loading can reach complete room-temperature elimination of HCHO under harsh conditions as listed in Table 1. The significant decrease of Pt loading amount resulted from the role of ~1 nm Pt nanoclusters by using Pt colloid as precursor, which facilitated the formation of Pt species and location of OH groups56. During the adsorption of HCHO, the high activity of OH species led to the formation of formates from the reaction between HCHO and OH to HCOO and H2O57. Moreover, the metallic Pt species were favorable for the activation of O2 as atomic O, which was confirmed by microcalorimetry results in Fig. 6. The atomic O facilitated more transformation of HCHO to formates with the production of OH groups or adsorbed H2O species29. It also reacted with the adsorbed H2O species to form OH groups58, which can work well for the oxidation of HCHO on Pt-NC catalyst with such low loading of 0.08 wt%. Thus, even under the condition of RH = 0% as shown in Fig. 4, the 0.08 Pt-NC catalyst still exhibited high HCHO conversion, for which the decomposition of formates followed the pathway of HCOO + OH \(\rightarrow\) CO2 + H2O as reported previously20,57,59. Both the preferential formates formation and more O2 activation contributed to the high performance of Pt nanoclusters either in dry or in wet conditions.

As for Pt single-atoms, it was reported that the bonding OH species stabilized by alkali metals altered HCHO oxidation pathway via the reaction between surface OH and formate species. The presence of larger amount of 1 wt% Pt atoms can provide ample OH species that totally eliminated HCHO at room temperature20. Nevertheless, on the 0.01 Pt-SAC or 0.06 Pt-Mix catalyst, the OH groups may be not enough due to the ultra-low loading of Pt. Furthermore, O2 was not well activated and the oxidation capacity of these catalysts was not high enough to convert HCHO to formates, not to mention the final CO2 as shown in Figs. 2, 7. Besides, it was also found that the supply of more OH species could enhance the adsorption and transformation of HCHO on Pt nanoparticle catalysts with sizes higher than 2 nm59. However, the wide-size distribution and lower exposure of Pt species for these nanoparticles resulted in the waste of Pt usage and lower metal utilization efficiency34,36,39. Relatively, the higher dispersion of ~1 nm Pt nanoclusters exhibited the abundant presence of OH species and stronger O2 activation capacity, thus maintaining excellent efficiency in HCHO oxidation under conditions of wide RH from 0 to 75% with loading of only 0.08 wt%. Moreover, these Pt nanoclusters showed good performance for room-temperature HCHO removal on different supports such as TiO2, FeOx, and Al2O3, probably through the same reaction route with similar activation energy as shown in Fig. 8. Therefore, compared with Pt single-atoms or nanoparticles, Pt nanoclusters promote the adsorption and transformation of HCHO to favorable formates. In addition, this size scale facilitates more activation of O2 and formation of OH species, which can particularly react with formates to release CO2 more facile through a lower reaction barrier, then significantly decreasing the loading amount of Pt.

In summary, the ~1 nm Pt nanocluster catalyst with ultra-low loading of 0.08 wt%, orders of magnitude lower than most of previous Pt-based catalyst, was successfully synthesized, which significantly enhanced the catalytic performance in HCHO room-temperature oxidation and exhibited a good stability for long-term run under harsh conditions of high HCHO concentration and wide relative humidity. As comparisons, the catalysts with other specific size as single-atoms and nanoparticles were tailor-made. There was a volcano-like relationship between Pt size and activity. The ~1 nm Pt nanoclusters owned ~2.4 times higher specific rate for HCHO conversion than nanoparticles and ~36.6 times than single-atoms. It was identified that Pt nanoclusters promoted more activation of O2 and easier formation of formates than other size scale, which then reacted with OH to produce CO2 via lower activation energy. More importantly, the ~1 nm Pt nanoclusters with such low loading presented a good versatility for room-temperature elimination of HCHO whether supporting on “active” FeOx or “inert” Al2O3. Considering the identification of active center with rather uniform species, our study can shed light on the design of more economic noble-metal catalysts with optimal catalytic performance but lower loadings.

Methods

Preparation of supports

The support of high surface area TiO2 was prepared by the hydrolysis method30. In vigorous stirring conditions, 17.2 g TTBT was added dropwise into 800 mL ultra-pure water and then stirred for 2 h. The resulting precipitate was filtered and washed with 1 L ultra-pure water. The filter cake was dried at 100 °C overnight and then calcined under air flow at 400 °C for 4 h. The support of Fe2O3 was prepared by conventional precipitation method. Under stirring at 80 °C, an aqueous solution of Fe(NO3)3 with certain mass was added dropwise to a NaOH solution at a rate of 3 mL min−1 and then the pH value of the resulting solution was controlled at around 9. The obtained solid was dried at 80 °C for 12 h and then calcined at 400 °C for 6 h. Aluminum oxide (γ-Al2O3) were purchased from Aladdin Company.

Preparation of nanocluster or nanoparticle catalyst

The precursors of Pt colloid with specific size were synthesized by alkaline EG reduction26,27 and then deposited on TiO2 via the colloidal deposition method13,28. Typically, a solution of NaOH in EG (50 mL, 0.05 mol L−1) was poured into a solution of H2PtCl6·6H2O in EG (50 mL, 3.86 mol L−1). The resulting colloidal solution was heated at 160 °C for 3 h under inert gas atmosphere (Ar), which was denoted as Colloid-NC. To fabricate larger size Pt colloid, the concentration of H2PtCl6 in EG was increased to 38.6 mol L−1 and water was added into the solution with the volume ratio of EG/water as 9:1. The concentration of NaOH in EG was changed to 0.5 mol L−1. The other preparation parameters and operations were the same as above and the product was denoted as Colloid-NP. Then the Pt Colloid-NC or NP with appropriate amount was deposited onto the TiO2 with impregnation method. The obtained suspension was filtered and washed by 1 L hot ultra-pure water and calcined at 400 °C for 2 h. The Pt nanoclusters supported on other oxides such as FeOx and Al2O3 were prepared following processes similar to those used to prepare the samples supported on TiO2.

Preparation of single-atom or subnanocluster catalyst

The Pt/TiO2 catalysts with single-atom or mixed dispersion were prepared by the DP method24,29. Typically, 100 mL of the H2PtCl6 aqueous solution with specific concentration was dropwise added into the TiO2 suspension at a rate of 3 mL min−1 under vigorous stirring. After that, the pH value of the mixture was modulated by NaOH to maintain at around 9.5. After reacting for 3 h and aging for 1 h, the suspension was filtered with 1 L hot ultra-pure water washing to remove the chloride ions (tested by AgNO3 solution). The obtained filter cake was dried at 80 °C overnight and calcined in muffle furnace at 400 °C for 2 h.

Catalyst structure characterization

Pt loadings of the catalysts were determined by inductively coupled plasma spectrometer (ICP) on an IRIS Intrepid II XSP instrument (Thermo Electron Corporation). Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface areas of the catalysts were detected on a Micromeritics ASAP 2010 apparatus by nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms at −196 °C. X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiments were carried out on the PW3040/60 X’pert PRO (PANalytical) diffractometer of which the voltage and current were, respectively, 40 kV and 40 mA with a radiation source of Cu Kα (λ = 0.15432 nm). X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were measured on a Thermofisher ESCALAB 250 Xi apparatus to obtain the surface compositions and binding energies of the catalysts. Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV, 15 kV, 10.8 mA) at an energy scale calibrated versus adventitious carbon (C1s peak at 284.6 eV) was used. Before test, the catalysts were reduced in H2. HRTEM images were acquired on a Tecnai G2 F30 S-Twin transmission electron microscope operating at 300 kV. The aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-HAADF-STEM) images were obtained on a JEOL JEM-ARM 200F equipped with a CEOS probe corrector. The sample powder was prereduced by H2.

In situ DRIFTS experiment

The in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectra (DRIFTS) were collected via a BRUKER Vertex 70 spectrometer equipped with a MCT detector. The samples were pretreated in 20 vol.% H2/He at 300 °C for 30 min and then purged with He for 1 h. At first, the background spectrum was recorded. The gas of HCHO was generated by helium passing through a paraformaldehyde container with a flow rate of 30 mL min−1. The resulted 100 ppm HCHO in He was then injected into the reaction cell at room temperature. After that, a flow of helium was purged. Then O2 + H2O was introduced by bubbling 20% O2/He through a water reservoir at room temperature. All the DRIFTS were collected by subtracting the background.

O2 microcalorimetric adsorption

Microcalorimetric experiments of O2 adsorption were performed via a BT 2.15 heat-flux calorimeter (Seteram, France). Prior to the adsorption, the catalyst was pretreated in 20 vol.% H2/He using a special treatment cell at 300 °C for 30 min. The adsorption experiment was conducted at 40 °C.

TPSR experiments

TPSR tests were conducted in a fixed-bed flow system by detecting the effluent gases with an on-line mass spectrometer (MS). Firstly, the sample was reduced in H2 and subsequently purged with He cooling to ambient temperature. The HCHO gas was introduced into the reaction tube for adsorption. After that, the temperature was ramped from 20 °C to 400 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1 under the atmosphere of flowing gas of O2 + H2O, which was obtained by bubbling 20% O2/He through a water reservoir at room temperature.

Catalyst performance tests

The perfo\rmance tests of all catalysts in HCHO oxidation were carried out in a continuous-flow fixed-bed reactor under atmospheric pressure. Before evaluation, 100 mg catalyst was reduced by 20 vol% H2/He in a flow of 20 mL min−1 at 300 °C. Then the feed gases, which were composed of 160 ppm HCHO, 20 vol% O2 and 50% RH (relative humidity) by He balanced at a total flow rate of 50 mL min−1 corresponding to a weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 30,000 mL h−1 gcat−1, was introduced into the reactor tube. To investigate the capacities of HCHO removal, the initial concentration of formaldehyde was increased from 160 to 1300 ppm by tuning the flow rate of helium, which passed through the paraformaldehyde container and changing the temperature of container. In addition, the relative humidity (RH) was modulated by the flow rate of helium passing through a water bubbler. The HCHO conversion was detected by an on-line gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890B). Due to the low concentration of feed gas, the gas chromatograph was equipped with hydrogen flame ionization detector (FID) and Ni catalyst convertor used to transform carbon oxides quantitatively into methane. The product of CO2 was detected without other carbonaceous compounds in the outlet gas over all catalysts.

The conversion of HCHO was expressed as [CO2]out/[CO2]all, where [CO2]out represented the generated concentration of CO2 at a certain temperature and [CO2]all was the concentration of CO2 when 100 % HCHO conversion was achieved. Simultaneously, HCHO concentration was calibrated by the CO2 concentration which was determined by the external standardization method.

HCHO conversion (XHCHO) was obtained by the Eq. (1):

For kinetic tests, the specific reaction rates and TOFs for HCHO oxidation at different temperatures over Pt-based catalysts were measured under differential conditions with HCHO conversion below 20% by changing the space velocity. The samples were diluted with quartz sand for the tests. The reaction rate of the catalysts was calculated by the Eq. (2):

Where fHCHO and mcat represented HCHO molar gas flow rate in mol h−1 and the mass of catalyst in the fixed-bed, respectively; n was the loading amount of Pt.

TOF was calculated based on the specific rates and Pt dispersions by the Eq. (3):

Where MPt was the molar weight of Pt and DPt represented the dispersion of Pt. The Pt species were considered as 100% dispersion on TiO2 for Pt single-atom catalyst, while for other catalysts the Pt dispersion was measured by CO adsorption microcalorimetry and supposed that the stoichiometric ratio of adsorbed CO/Pt was 1.

The apparent activation energies over the Pt/TiO2 and other Pt-based catalyst were calculated according to the Arrhenius equation (4).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. All other relevant source data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Vajda, S. et al. Subnanometre platinum clusters as highly active and selective catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Nat. Mater. 8, 213–216 (2009).

Yu, W. T., Porosoff, M. D. & Chen, J. G. Review of Pt-based bimetallic catalysis: from model surfaces to supported catalysts. Chem. Rev. 112, 5780–5817 (2012).

Liu, L. C. & Corma, A. Metal catalysts for heterogeneous catalysis: from single atoms to nanoclusters and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 118, 4981–5079 (2018).

Yang, X. F. et al. Single-atom catalysts: a new frontier in heterogeneous catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1740–1748 (2013).

Qiao, B. T. et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 3, 634–641 (2011).

Wang, A. Q., Li, J. & Zhang, T. Heterogeneous single-atom catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 65–81 (2018).

Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. & Gates, B. C. Atomically dispersed supported metal catalysts. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 3, 545–574 (2012).

Yang, M. et al. A common single-site Pt(II)-O(OH)x-species stabilized by sodium on “active” and “inert” supports catalyzes the water-gas shift reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 3470–3473 (2015).

Hou, Y., Nagamatsu, S., Asakura, K., Fukuoka, A. & Kobayashi, H. Trace mono-atomically dispersed rhodium on zeolite-supported cobalt catalyst for the efficient methane oxidation. Commun. Chem. 1, 41 (2018).

Yan, H. et al. Bottom-up precise synthesis of stable platinum dimers on graphene. Nat. Commun. 8, 1070 (2017).

Jeong, H. et al. Fully dispersed Rh ensemble catalyst to enhance low-temperature activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9558–9565 (2018).

Ding, K. L. et al. Identification of active sites in CO oxidation and water-gas shift over supported Pt catalysts. Science 350, 189–192 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Identifying size effects of Pt as single atoms and nanoparticles supported on FeOx for the water-gas shift reaction. ACS Catal. 8, 859–868 (2018).

Kwak, J., Kovarik, L. & Szanyi, J. Heterogeneous catalysis on atomically dispersed supported metals: CO2 reduction on multifunctional Pd catalysts. ACS Catal. 3, 2094–2100 (2013).

Wei, H. S. et al. Remarkable effect of alkalis on the chemoselective hydrogenation of functionalized nitroarenes over high-loading Pt/FeOx catalysts. Chem. Sci. 8, 5126–5131 (2017).

Ammal, S. C. & Heyden, A. Water-gas shift activity of atomically dispersed cationic platinum versus metallic platinum clusters on titania supports. ACS Catal. 7, 301–309 (2017).

Torres, J. Q., Royer, S., Bellat, J. P., Giraudon, J. M. & Lamonier, J. F. Formaldehyde: catalytic oxidation as a promising soft way of elimination. ChemSusChem 6, 578–592 (2013).

Bai, B. Y., Qiao, Q., Li, J. H. & Hao, J. M. Progress in research on catalysts for catalytic oxidation of formaldehyde. Chin. J. Catal. 37, 102–122 (2016).

Zhang, C. B. & He, H. A comparative study of TiO2 supported noble metal catalysts for the oxidation of formaldehyde at room temperature. Catal. Today 126, 345–350 (2007).

Zhang, C. B. et al. Alkali-metal-promoted Pt/TiO2 opens a more efficient pathway to formaldehyde oxidation at ambient temperatures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 9628–9632 (2012).

Cui, W. Y. et al. Pt supported on octahedral Fe3O4 microcrystals as a catalyst for removal of formaldehyde under ambient conditions. Chin. J. Catal. 39, 1534–1542 (2018).

Huang, H. B. et al. Highly dispersed and active supported Pt nanoparticles for gaseous formaldehyde oxidation: Influence of particle size. Chem. Eng. J. 252, 320–326 (2014).

Herzing, A. A., Kiely, C. J., Carley, A. F., Landon, P. & Hutchings, G. J. Identification of active gold nanoclusters on iron oxide supports for CO oxidation. Science 321, 1331–1335 (2008).

Guan, H. L. et al. Enhanced performance of Rh1/TiO2 catalyst without methanation in water-gas shift reaction. AIChE J. 63, 2081–2088 (2016).

Lin, J. et al. Remarkable performance of Ir1/FeOx single-atom catalyst in water gas shift reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 15314–15317 (2013).

Wang, Y., Ren, J. W., Deng, K., Gui, L. L. & Tang, Y. Q. Preparation of tractable platinum, rhodium, and ruthenium nanoclusters with small particle size in organic media. Chem. Mater. 12, 1622–1627 (2000).

Sonström, P., Arndt, D., Wang, X. D., Zielasek, V. & Bäumer, M. Ligand capping of colloidally synthesized nanoparticles-a way to tune metal-support interactions in heterogeneous gas-phase catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 3888–3891 (2011).

Lin, J. et al. Little do more: a highly effective Pt1/FeOx single-atom catalyst for the reduction of NO by H2. Chem. Commun. 51, 7911–7914 (2015).

Sun, X. C. et al. Complete oxidation of formaldehyde over TiO2 supported subnanometer Rh catalyst at ambient temperature. Appl. Catal. B 226, 575–584 (2018).

Ren, D. et al. An unusual chemoselective hydrogenation of quinoline compounds using supported gold catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17592–17598 (2012).

Liu, Y., Jia, C. J., Yamasaki, J., Terasaki, O. & Schüth, F. Highly active iron oxide supported gold catalysts for CO oxidation: how small must the gold nanoparticles be? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 5771–5775 (2010).

Zhang, C. B., Li, Y. B., Wang, Y. F. & He, H. Sodium-promoted Pd/TiO2 for catalytic oxidation of formaldehyde at ambient temperature. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 5816–5822 (2014).

Li, Y. B., Chen, X. Y., Wang, C. Y., Zhang, C. B. & He, H. Sodium enhances Ir/TiO2 activity for catalytic oxidation of formaldehyde at ambient temperature. ACS Catal. 8, 11377–11385 (2018).

Kwon, D. W., Seo, P. W., Kim, G. J. & Hong, S. C. Characteristics of the HCHO oxidation reaction over Pt/TiO2 catalysts at room temperature: The effect of relative humidity on catalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B 163, 436–443 (2015).

An, N. H. et al. Catalytic oxidation of formaldehyde over different silica supported platinum catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 215-216, 1–6 (2013).

Yu, X. H. et al. Facile Controlled synthesis of Pt/MnO2 nanostructured catalysts and their catalytic performance for oxidative decomposition of formaldehyde. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116, 851–860 (2012).

Xu, Z. H., Yu, J. G. & Jaroniec, M. Efficient catalytic removal of formaldehyde at room temperature using AlOOH nanoflakes with deposited Pt. Appl. Catal. B 163, 306–312 (2015).

Yang, T. F., Huo, Y., Liu, Y., Rui, Z. B. & Ji, H. B. Efficient formaldehyde oxidation over nickel hydroxide promoted Pt/γ-Al2O3 with a low Pt content. Appl. Catal. B 200, 543–551 (2017).

Yang, X. Q. et al. Interface effect of mixed phase Pt/ZrO2 catalysts for HCHO oxidation at ambient temperature. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 13799–13806 (2017).

Wang, L. et al. Highly active Pt/NaxTiO2 catalyst for low temperature formaldehyde decomposition. Appl. Catal. B 219, 301–313 (2017).

Raskó, J., Kecskés, T. & Kiss, J. Adsorption and reaction of formaldehyde on TiO2-supported Rh catalysts studied by FTIR and mass spectrometry. J. Catal. 226, 183–191 (2004).

Yan, Z. X., Xu, Z. H., Yu, J. G. & Jaroniec, M. Highly active mesoporous ferrihydrite supported Pt catalyst for formaldehyde removal at room temperature. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 6637–6644 (2015).

Lin, M. Y. et al. Highly active and stable interface derived from Pt supported on Ni/Fe layered double oxides for HCHO oxidation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 7, 1573–1580 (2017).

Huang, Z. W. et al. Catalytically active single-atom sites fabricated from silver particles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 124, 4274–4279 (2012).

Guan, H. L. et al. Catalytically active Rh sub-nanoclusters on TiO2 for CO oxidation at cryogenic temperatures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 2820–2824 (2016).

Widmann, D. & Behm, R. J. Activation of molecular oxygen and the nature of the active oxygen species for CO oxidation on oxide supported Au catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 740–749 (2014).

Uner, D. & Uner, M. Adsorption calorimetry in supported catalyst characterization: Adsorption structure sensitivity on Pt/γ-Al2O3. Thermochim. Acta 434, 107–112 (2005).

Chen, B. B., Shi, C., Crocker, M., Wang, Y. & Zhu, A. M. Catalytic removal of formaldehyde at room temperature over supported gold catalysts. Appl. Catal. B 132-133, 245–255 (2013).

Colussia, S. et al. Room temperature oxidation of formaldehyde on Pt-based catalysts: a comparison between ceria and other supports (TiO2, Al2O3 and ZrO2). Catal. Today 253, 163–171 (2015).

Huang, H. B. & Leung, D. Y. C. Complete elimination of indoor formaldehyde over supported Pt catalysts with extremely low Pt content at ambient temperature. J. Catal. 280, 60–67 (2011).

Zhu, X. F., Yu, J. G., Jiang, C. J. & Cheng, B. Catalytic decomposition and mechanism of formaldehyde over Pt-Al2O3 molecular sieves at room temperature. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 6957–6963 (2017).

Quinson, J. et al. Investigating particle size effects in catalysis by applying a size-controlled and surfactant-free synthesis of colloidal nanoparticles in alkaline ethylene glycol: case study of the oxygen reduction reaction on Pt. ACS Catal. 8, 6627–6635 (2018).

Li, G. & Li, L. Highly efficient formaldehyde elimination over meso-structured M/CeO2 (M=Pd, Pt, Au and Ag) catalyst under ambient conditions. RSC Adv. 5, 36428–36433 (2015).

Zhang, L. et al. Complete oxidation of formaldehyde at room temperature over an Al-rich Beta zeolite supported platinum catalyst. Appl. Catal. B 219, 200–208 (2017).

Yan, Z. X., Xu, Z. H., Yu, J. G. & Jaroniec, M. Enhanced formaldehyde oxidation on CeO2/AlOOH-supported Pt catalyst at room temperature. Appl. Catal. B 199, 458–465 (2016).

Schrader, I. et al. Surface chemistry of “unprotected” nanoparticles: a spectroscopic investigation on colloidal particles. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 17655–17661 (2015).

Li, Y. B. et al. High temperature reduction dramatically promotes Pd/TiO2 catalyst for ambient formaldehyde oxidation. Appl. Catal. B 217, 560–569 (2017).

van der Niet, M. J., den Dunnen, A., Juurlink, L. B. & Koper, M. T. Co-adsorption of O and H2O on nanostructured platinum surfaces: does OH form at steps? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 6572–6575 (2010).

Huang, S. Y., Cheng, B., Yu, J. G. & Jiang, C. J. Hierarchical Pt/MnO2-Ni(OH)2 hybrid nanoflakes with enhanced room-temperature formaldehyde oxidation activity. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 12481–12488 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21878283, 21576251, 21573232, 21676269), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (2017223), the “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese academy of Sciences (XDB17020100), and the National Key projects for Fundamental Research and Development of China (2016YFA0202801).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S. performed the catalyst synthesis, characterizations, catalytic tests, and paper writing. J.L. and X.W. conceived the research and co-wrote this manuscript. Y.C. and Y.W. participated in catalyst preparation and characterizations. L.L. helped to discuss the performance results and analyze the DRIFTS results. S.M. and X.P. conducted the STEM examinations and helped the result analysis. All authors contributed to the discussions and corrections during the writing process.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, X., Lin, J., Chen, Y. et al. Unravelling platinum nanoclusters as active sites to lower the catalyst loading for formaldehyde oxidation. Commun Chem 2, 27 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0129-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0129-0

This article is cited by

-

Recent developments of supported and magnetic nanocatalysts for organic transformations: an up-to-date review

Applied Nanoscience (2023)

-

Single-atom site catalysts for environmental catalysis

Nano Research (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.