Abstract

GeTe-Sb2Te3 pseudobinary system, especially Ge2Sb2Te5 alloy, is the most desirable material to be commercialized in phase change random access memory. Directly resolving the local atomic arrangement of Ge2Sb2Te5 during intermediate steps is an effective method to understand its transition mechanism from face-centered-cubic to hexagonal phases. In this study, we provide insights into the atomic arrangement variation during face-centered-cubic to hexagonal transition process in Ge2Sb2Te5 alloy by using advanced atomic resolution energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. Induced by thermal annealing, randomly distributed germanium and antimony atoms would migrate to the specific (111) layer in different behaviors, and antimony atoms migrate earlier than germanium atoms during the phase transition process, gradually forming intermediate structures similar to hexagonal lattice. With the migration completed, the obtained stable hexagonal structure has a partially ordered stacking sequence described as below: -Te-Sbx/Gey-Te-Gex/Sby-Te-Gex/Sby-Te-Sbx/Gey-Te- (x > y), which is directly related to the migration process. The current visual fragments suggest a gradual transition mechanism, and guide the performance optimization of Ge2Sb2Te5 alloy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A significant advancement in the semiconductor technology has led to the use of phase change memory (PCRAM) in a commercial product to perfect the storage system1,2,3. As the most important key material of PCRAM, Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST) alloy4,5, is proved to have long cyclability6, high density7, and nanosecond switching speed8 characteristics. Induced by thermal annealing, amorphous (a-) GST material will crystallize into a metastable face-centered-cubic (f-) structure (Fm\(\overline{3}\)m, a = 6.02 Å) at ~150 °C with a cationic Ge/Sb/vac f-sublattice and an anionic Te f-sublattice, accompanied by more than 4 orders of magnitude resistance decreasing9,10. Such a huge resistance contrast between a- and f-phase is utilized to realize information storage in GST based PCRAM devices11,12. If f-phase material was overheated, for example, 320–350 °C, it will transform into stable trigonal structure (P\(\overline{3}\)m1, a–b–c stacking sequence feature of (0001) planes) with a further resistance decreasing, which was often indexed with hexagonal (h-) phase (a = 4.20 Å, c = 16.96 Å)10,13.

Such a stable h-phase would worsen the storage performance due to the large reset current14, big volume shrinkage15, supernormal mechanical stress16,17, and bad cyclability18. The specific local atomic arrangements in h-phase may be also an advantage in recently proposed interfacial phase change memory (iPCM) devices19, however in traditional T-cell structure3, phase change material is deposited without precision crystallographic texture control, and poor-quality interface with multiple grains in h-phase requires substantially higher SET/RESET switching energy. Thus, preventing the formation of h-phase is still a critical issue for PCRAM application. Unfortunately, at the moment, the atomic motif of different crystalline structures in GST alloy has not even been unambiguously resolved. As for f-phase, Yamada et al. claimed that Te atoms occupy the anion sites, and Ge, Sb, and intrinsic vacancies randomly occupy the cation sites20,21, resulting in an atomic stacking sequence along [111] direction of f-lattice ([0001] direction in h-lattice) depicted as below: –(Te–Ge/Sb/Vacancy)–. While Sun et al. claimed that the stable configuration should make Ge, Sb atoms, and intrinsic vacancies locate in the separate layers22, and recently they calculated that f-phase is actually polymorphic, varying from randomly distributed vacancies to highly ordered vacancy layers23. By using an element-resolved atomic imaging method, Zhang et al. confirmed a randomly distributed vacancies f-phase24,25, while no direct element-resolved evidence was reported for the polymorphic state in f-phase at present. As regards to stable h-phase, it is characteristic of nine-layer stacking blocks along [0001] orientation, due to the immature of the analysis means, the exact atomic arrangement is still under debate, mainly including three possible stacking sequences along [0001] orientation: (a) Kooi model26: –(Te–Sb–Te–Ge–Te–Ge–Te–Sb–Te)–; (b) Petrov model27: –(Te–e–Te–Sb–Te–Sb–Te–Ge–Te)–; and (c) Matsunaga model28: –(Te–Ge0.44Sb0.56–Te–Ge0.56Sb0.44–Te–Ge0.56Sb0.44–Te–Ge0.44Sb0.56–Te)–. Density functional theory calculations demonstrated that the most stable configuration is favor to Kooi sequence22,29,30,31. While Da Silva et al. claimed that the stable configuration should make Ge and Sb atoms on the opposite side surrounded with Te atoms to release strain energy, and leads to the intermixing Ge and Sb atoms in the (0001) planes32. Controversy not only appears in the theoretical aspect, but also in the experimental observations. In the absorption coefficient experiment, it claims that the Petrov sequence fits better to the measurement33. However, the large broadening phenomenon observed in Raman peaks34, and the non-uniform contrast of cationic layers35,36 from high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image are both inclined to Matsunaga sequence.

Considering the plausible similar atomic sequence in f- and h-lattice, researchers tend to believe a diffusionless controlled mechanism should happen during the whole crystal transition process22,37. For example, the shearing martensitic mechanism with a twisting atomic movement38,39, the epitaxial growth mechanism through a continuous accumulation40,41, and recently, a vacancy ordering mechanism which emphasizes the critical role of the vacancy aggregation behavior24,25,42,43. Though above-mentioned mechanisms seem to be very intriguing, puzzles in the atomic arrangement of different structures, especially the intermediate (i-) state, obstruct the clarification of the exact transition mechanism. Hence, tracing the atom migration behavior during the whole process would be a crucial and effective method to deduce the transition mechanism.

Here, we show how initial f-phase transforms into stable h-phase at the atomic scale occurs using atomic resolution energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). More specifically, from initial f-phase to different degree i-phase and to h-phase, cationic atoms will gradually migrate to the specific (111) layers from the completely disordered state to partial ordered distribution. Besides, Ge and Sb atoms show different migration behaviors, resulting in different cationic ordered extent i-phases. In stable h-phase, Sb atoms aggregate in the outer cationic layers, while Ge atoms aggregate in the inner cationic layers in the nine-layer blocks, manifesting the following suggested stacking sequence: –Te–Sbx/Gey–Te–Gex/Sby–Te–Gex/Sby–Te–Sbx/Gey–Te– (x > y). Through the visual atomic identification of f-to-h transition fragments in GST material, we claim that it is a gradual change process dominated by the directed migration of Ge/Sb atoms, which provides a profound understanding of phase change mechanism between similar crystal structures, and guides the optimization of GST alloy for PCRAM application in the future.

Results

The direct visualization of f-phase arrangement on atomic level

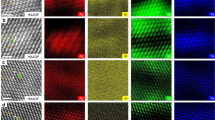

Figure 1 signifies the atomic arrangement of GST alloy in metastable f-phase annealed at 150 °C for 5 min. Owing to the incoherent scattering intrinsic of STEM-HAADF technique, the intensity of the HAADF image is roughly proportional to Z2 (ref. 44), where Z is the atomic number. In GST alloy, the atomic number of Ge, Sb, and Te is 32, 51, and 52, respectively, and the corresponding HAADF image projected along \([1\overline{1}0]\) orientation demonstrates a periodical contrast–intensity fluctuation in Fig. 1a, fitting well with the assumption that Ge and Sb atoms occupy cationic sites, and Te atoms occupy anionic sites24,25,37,45. After all, HAADF method is an indirect technology to analyze the atomic arrangement of the structure, we then used atomic EDS mapping technique46,47 to directly determine the location of different elements as depicted in Fig. 1b–d, which also shows a periodical contrast–intensity fluctuation for Ge (red), Sb (green), and Te (blue) elements taken from the yellow rectangle area. The associated EDS profile along [111] orientation was also inset in the right side of each image, which is integrated in its perpendicular direction, the \([11\overline2]\) orientation for f-phase. By evaluating the intensity of the profile, we could qualitatively evaluate the concentration of each element, and the almost same height level at each cationic layer unambiguously demonstrates the random distribution of three elements in initial f-phase. If we overlap the atomic mapping pictures of Ge, Sb, and Te elements as shown in Fig. 1e–h, it can be clearly seen that Te atoms occupy anionic sublattice, while Ge and Sb atoms occupy cationic sublattice with plenty of vacancy sites together considering the stoichiometric of the film, in line with the Yamada atomic model20 as inset in Fig. 1a.

Atomic resolution elemental maps of f-phase GST. a A prototype HAADF image of f-phase GST alloy projected along \([1\overline{1}0]\) orientation, exhibiting a periodical contrast–intensity fluctuation. The inset is the corresponding atomic model, and the distance between Te–Te layers is 0.350 ± 0.006 nm. Lines 1–6 denote the cationic layer, respectively. b–d Atomic resolution maps of Ge, Sb, and Te atoms taken from area 1, respectively. The EDS profiles along [111] orientation are presented on the right-hand side showing uniform height peaks. e–h The corresponding overlap results of every two elements by pairs, and the overlap of three elements, indicating that Ge/Sb atoms indeed occupy cationic sites, and Te atoms occupy anionic sites in f-phase. Scale bar: (a–h) 1 nm

Ordered cation migration during f-to-h transition process

Though literatures emphasize the diffusionless mechanism during the structure transition, to date, no direct evidence were given on atom arrangements in i-phase. In the following section, the atomic arrangement of different i-phases is discussed in detail to shed light on the transition mechanism. Figure 2a is the HAADF image of GST film annealed at 290 °C for 5 min projected along \([1\overline{1}0]\) orientation, in which cation migration has already proceeded. The inset atomic model shown in Fig. 2a indicates the position of cation and anion layers with typical f-phase stacking sequence. Compared to Fig. 1a, one of the most prominent changes is that two horizontal dark contrast atomic columns appear as denoted by arrows (lines 1 and 6), which are separated by nine-layer blocks. Extracted from the dark atomic columns (yellow rectangular region), the corresponding contrast profile along [111] orientation has a tendency to decrease from left to right side as shown in Fig. 2b. Area “A” shows uniform cation distribution almost same with Fig. 1. While the cationic layer atoms at areas “B” and “C” are partially missing, or move somewhere else. Besides, the atomic spacing of Te–Te layers above and below the dark atomic column also shows a decreasing trend, from 0.356 ± 0.008 nm (area “A”) to 0.346 ± 0.010 nm (area “B”) to 0.329 ± 0.010 nm (area “C”) as shown in the bottom of Fig. 2b, which may imply gradual migration of cationic atoms in the corresponding sites from “A” to “B” to “C”.

Atomic resolution elemental map of i-phase GST at initial stage. a The HAADF image of i-phase GST alloy projected along \([1\overline{1}0]\) orientation, the dashed white line along anionic atoms shows f-phase stacking feature. The atomic model is shown in the center area, and lines 1–6 denote the cationic layer, respectively. b HAADF image extracted from the yellow rectangle in (a), and the intensity profile is calculated from the dark columns (denoted as red rectangle in the lower part) exhibiting a decreasing intensity trend. c–h are the atomic mapping resolutions of Ge, Sb, and Te atoms taken from areas 2 and 3, respectively. The EDS profiles along [111] orientation are also presented on the right-hand side of each picture. Scale bar: (a–h) 1 nm

To verify it, atomic EDS mapping was utilized to explore the distribution of Ge, Sb, and Te elements in area 2 (denoted as magenta rectangle) shown in Fig. 2c–e and area 3 (denoted as orange rectangle) shown in Fig. 2f–h. The corresponding overlaps of three elements in areas 2 and 3 confirm that Ge and Sb columns occupy the cationic sites, while Te columns occupy the anionic sites in Supplementary Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 5. When the cation starts to migrate, Sb columns no longer retain a disordered distribution in cationic site, and the corresponding EDS profile clearly shows that lines 1 and 6 possess lower peaks than other lines. As a contrast for Ge, it still shows a uniform contrast in every cationic site, and the corresponding EDS profiles projected along [111] orientation have the same level from lines 1 to 6. Therefore, the observed dark contrast in area 2 would be firstly ascribed to the migration of Sb atoms.

When moving to area 3, with a further decreased concentration of cationic layer atoms in yellow rectangular region of Fig. 2a, the migrated cation is still mainly dominated by Sb, showing a deeper migration behavior in Fig. 2g, since the peaks of the EDS profiles in lines 2 and 5 are much higher than those in lines 1 and 6. Meanwhile, the migration of Ge atoms starts, manifesting as slightly higher peaks in lines 3 and 4 than those of in lines 1, 2, 5, and 6 from its corresponding EDS profile in Fig. 2f. Hence, the migration of Ge atoms occurs after Sb atoms. As for Te columns, it always shows a uniform contrast with a nearly same height profile, indicating that Te atoms as stable as frames here.

To further explore cationic migration in i-phase, GST film was annealed at 290 °C for 30 min. Figure 3a is the corresponding HAADF image projected along \([1\overline{1}0]\) orientation, where lines 1 and 6 show very dark contrasts in HAADF image and the corresponding Te–Te atomic spacing above and below the declining cationic layer is about 0.304 ± 0.007 nm, a value close to the Van der Waals gap spacing expected in h-phase (0.285 nm)28, indicating that more and more Ge/Sb atoms have migrated to the neighbor cationic layers. In this i-state, Ge/Sb atoms still occupy the cationic sites, and Te atoms occupy anionic sites as shown in Fig. 3e and Supplementary Figure 6. For more, Te always shows a uniform contrast in anionic sites depicted in Fig. 3d, while a vast of Ge and Sb atoms in lines 1 and 6 have migrated into adjacent nine-layer building blocks as shown in Fig. 3b, c, resulting in lowest peaks in the dark contrast cationic layers. Inspecting the peaks in lines 1 and 6 more carefully, we can find the two peaks are very significant for Ge atoms in Fig. 3b, while no such obvious peaks can be found for Sb atoms in Fig. 3c, demonstrating a deeper migration behavior for Sb element. This evidence can also explain the very dark contrast in lines 1 and 6 observed from HAADF image, since the intensity of HAADF is more sensitive for Sb (Z = 51) than the case for Ge (Z = 32), thus a deeper migration behavior of Sb element would significantly reduce the intensity of HAADF image. Besides, Ge and Sb elements do not follow the same migration law, and Ge atoms gradually converge to the middle of nine layers building, which is reflected in that lines 3 and 4 have the highest peaks along [111] direction compared to other lines as shown in Fig. 3b. Sb atoms seem like the edge side of nine layers building block, as shown in Fig. 3c, and the peaks in lines 2 and 5 are significantly higher than the situation in other lines.

Atomic resolution elemental maps of i-phase GST at a deeper migration degree. a HAADF image of i-phase GST alloy projected along \([1\overline{1}0]\) orientation. Lines 1–6 denote the cationic layer, respectively. b–e The atomic resolution maps of Ge, Sb, and Te atoms and the overlay of three elements taken from area 4 (denoted as yellow rectangle). The EDS profiles along [111] orientation are present on the right-hand side in every picture. Scale bar: (a–e) 1 nm

Directly resolving the atomic arrangement of h-phase

Even in the deepest migration case in area 4, the alloy still retains the cubic stacking sequence. If we keep raising the annealing temperature, cubic lattice of GST alloy will change into h-state. Figure 4 exhibits the atomic EDS mapping results of h-GST structure projected along \([2\overline{1}\overline{1}0]\) orientation (\([1\overline{1}0]\) orientation in f-phase) after annealing at 350 °C for 5 min. By inspecting the STEM-HAADF image in Fig. 4a, it is seen that the anionic atoms have a mismatch as denoted by the dashed lines between adjacent building blocks, showing a typical h-phase feature. The distance of Van der Waals gap is about 0.288 ± 0.008 nm, very close to the value (0.285 nm) extracted from X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiment28. Similar to f-phase, Ge and Sb atoms still occupy cationic sites, while Te atoms occupy anionic sites as shown in Supplementary Figure 7. In h-phase, the associated EDS profile along [0001] orientation (corresponding [111] orientation in f-phase) was also inset in the right side of each image, which is integrated in its perpendicular direction, here, the \([01\overline{1}0]\)orientation. From the Ge/Sb atomic mapping shown in Fig. 4b, c, a vast majority of Ge and Sb atoms in lines 1 and 6 have already migrated away to other cationic layers. In the blocks, Ge atoms are concentrated in the inner cationic layers (lines 3 and 4), while Sb atoms like to stay in the outer cationic layers (lines 2 and 5), similar to the situation in area 4. As for Te element, it still retains a uniform contrast, except a small lattice mismatch between adjacent blocks (denoted by three translucence lines), a fingerprint for h-lattice. Previously, Lotnyk et al. also concluded a similar atomic arrangement by comparing simulation and experimental intensity of the STEM-HAADF image48, while in this report we can directly see the atomic arrangement of h-phase of GST alloy from the advanced atomic-resolved EDS mapping results without additional simulation. Furthermore, it is clear that there is a high similarity between h- and i-phases on the atomic arrangement side, which strongly suggests that f-to-h structural transition could fluently proceed by gradually cation migration.

Atomic resolution elemental maps of h-phase GST. a HAADF image of h-phase GST alloy projected along \([2\overline{1}\overline{1}0]\) orientation. Two dark contrast columns signify the Van der Waals gap labeled as lines 1 and 6, in which the Te–Te distance is about 0.288 ± 0.008 nm. Lines 2–5 denote the cationic layer in the nine-layer building block, respectively. b–d The atomic resolution maps pictures of Ge, Sb, and Te atoms taken from cyan rectangle in (a). The EDS profiles along [0001] orientation are present on the right-hand side in every picture. e The Ge/Sb ratio comparison between the experiment result and Matsunaga model. The pink line represents that the occupancy of Ge and Sb is same in cationic layers. Scale bar: (a–d) 1 nm

Qualitatively, we have effectively traced the migration behavior of Ge/Sb elements during f-to-h transition, while it would be much complicated when conducting quantitatively concentration analysis. Roughly, considering that no obvious peaks can be found in lines 1 and 6, it is reasonable to conclude that Ge and Sb atoms tend to locate in the nine-layer building blocks in h-phase. Therefore, after extracting the EDS counts of each cationic layer for Ge and Sb elements from the raw data, we can roughly evaluate the occupancy of Ge and Sb atoms in each cationic layer, respectively. Note that, due to the elastic and thermal scattering of the electron probe49,50, there is a non-negligible contribution of EDS signal from the nearby columns to the interest columns, and every atomic column (cationic/anionic) has signal of three elements as shown in the Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Table 1, and Supplementary Figure 8, which would obstruct the actual elements concentration ratio, a similar experiment report was also previously discussed in SrTiO3 sample49. Regardless of the intrinsic defects from the electron probe, the occupy ratios of Ge/Sb from cationic layer 2 to 5 were plotted (data processing and discussion are shown in the Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3) and compared with the curve calculated from Matsunaga model in Fig. 4e, where the dashed pink represents that the same occupancy ratio for Ge and Sb. The obtained curve for Ge/Sb occupancy ratios in each cationic layer still has the same occupancy trend with Matsunaga model, that is, Ge element prefers the inner cationic layers and Sb element likes the outer cationic layers in the blocks.

Thermally-induced f-to-h phase transition mechanism

After obtaining the atomic distribution in different crystalline states, we can draw a clear scenario of the thermally-induced f-to-h phase transition for GST film at the atomic scale as shown in Fig. 5. At initial f-phase, Ge, Sb, and vacancies randomly occupy the cationic sites. When the temperature rises, cationic atoms in layer I (corresponding to (111) layer in f-phase) start to migrate to the nearby vacancy sites in layer II, and Sb atoms move earlier than Ge atoms as denoted by the arrows in Fig. 5a, forming a vacancy aggregation area in layer I as shown in Fig. 5b afterwards. The earlier Sb migration behavior may be ascribed to the migration energy barriers difference between Sb and Ge. Previously, Zhang et al. found that the migration energy barrier to move one Sb atom to the vacancy site is smaller than to move one Ge atom by using the nudged elastic band (NEB) method25. Sun et al. also obtained a similar conclusion from the viewpoint of diffusion energy23, specifically, the diffusion energy to move two Sb atoms from the Te–Te vacancy layer to the Sb atomic layer (Eact = 0.026 eV) is smaller than the case in Ge atom (Eact = 0.035 eV), and the reverse process for both elements would be significantly higher. Afterwards, the rest of cationic atoms in layer I, mainly the Ge atoms, would gradually migrate to layer III via the transition layer II as denoted by the arrows in Fig. 5b. This process also seems to be related to the energy barrier differences for Ge and Sb atoms in layer II after a plenty of Sb atoms have occupied in layer II, which results in a higher migration energy barrier for Sb atoms. After a majority of Ge and Sb atoms in layer I have already migrated to the vacancy sites in layer II and layer III, the bonding between Te–Te layers is nearly negligible22, and the atomic arrangement in the nine-layer building block of f-phase is very similar to that in the h-structure, ready for the final transformation as shown in Fig. 5c. At last, a slight slip of stacking blocks along \([\overline{2}11]\) orientation (\([10\overline{1}0]\) orientation in h-phase) will eventually form the h-structure in Fig. 5d, with a stacking sequence similar to Matsunaga model.

A schematic scenario of the f-to-h phase transition. a The initial f-phase projected along [111] direction, in which cationic sites are randomly occupied by Ge, Sb, and vacancy. Red and green arrows denote the possible migration paths of the cationic atoms from layer I to layer II induced by thermal annealing. b The atomic configuration of i-phase after the migration process described in (a). Red and green arrows denote the possible migration paths of the cationic atoms from layer I to layer III via the transition layer II afterwards. c The atomic configuration of a deeper migration extent i-phase after the majority of Ge and Sb atoms in layer I have migrated, h-lattice-like atom arrangement makes the stacking block easily to slip to transition into h-phase. Orange arrow denotes the slip direction of the block. d The atomic configuration for the stable h-phase projected along [0001] direction, where Ge element prefers the inner cationic layers and Sb element likes the outer cationic layers in the blocks

Though many literatures claim that Kooi sequence is the stable configuration in h-phase, in which Sb completely occupy the outer layers and Ge occupy the inner layers, the hierarchy in energy between Kooi sequence and Matsunaga sequence is very small (just less than 5 meV per atom), indicating that the mentioned stacking sequences are both energy favorable. In fact, the difference in energy between Kooi sequence and Matsunaga sequence reported by Sun et al. (2 meV/atom) is of the same order of magnitude expected for the free energy contribution (at 300 K) due to the configuration entropy of the disordered (intermixing) Matsunaga sequence (\(\frac{4}{9}k_BT\,{\mathrm{In}}\,2 = 8\,{\mathrm{meV/atom}}\), in which kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature) as pointed by Caravati et al.34. One may doubt the possible atomic movement process making Matsunaga sequence transform into Kooi sequence induced by further annealing, for example, interchanging the position between Ge and Sb atoms in the blocks. After the cationic migration process, the majority of the vacant positions would be occupied by Ge or Sb atoms except for Van der Waals gap, though there may be still some excess vacancies exist in the nine-layer building according to the conducting transport measurements51, such concentrations of excess vacancies compatible with the experimental carrier densities are very small. Thus, the proposed interchanging process seems to be difficult than the migration behavior which was assisted with a lot of random vacancies in f-phase. Interestingly, Matsunaga even found that the mixture Ge/Sb situation in h-phase still retains when annealed up to 923 K28, close to the melting temperature of the alloy52. Therefore, we speculate that the obtained Matsunaga sequence-like h-phase arrangement is a stable configuration which is much related to the forming process, that is, the different migration behaviors of Ge and Sb atoms makes an unbalanced cationic distribution in the obtained h-phase. Besides, the present configuration also leads to a more favorable charge balance in the three coordinated edge Te atoms, since SbIII atoms possess a higher oxidation state than Ge[II 53.

Discussion

In summary, by utilizing advanced atomic-resolved EDS mapping technique, we systematically explore the atomic arrangement of different crystalline state during f-to-h phase transformation. Under external thermal annealing, randomly distributed Ge and Sb atoms gradually migrate to the neighbor (111) cationic layers, forming nine-layer blocks of i-phase very similar to h-lattice. The migration process is partial orderly, Sb atoms migrate earlier than Ge atoms, meanwhile, Ge element prefers the inner cationic layers, and Sb element likes the outer cationic layers in the formed h-lattice-like stacking blocks. The deeper Ge/Sb migration degree of i-phase, the closer the atomic arrangement is to the h-lattice. In the final nine-layer building block of h-phase, Sb atoms aggregate in the outer cationic layers, and Ge atoms aggregate in the inner cation layers, forming the following suggested stacking sequence: –Te–Sbx/Gey–Te–Gex/Sby–Te–Gex/Sby–Te–Sbx/Gey–Te– (x > y) which is similar to the Matsunaga model. In short, through the visual atomic identification of f-to-h transition fragments in GST material, we have connected the whole transition process at atomic level step by step, and successfully solved a crucial problem which has been a source of controversy and debate in the past. At the atomic scale, the key to prevent the formation of h-phase in GST should restrain the migration behavior of Ge and Sb atoms, for example, doping appropriate element into the cationic sites to reduce the vacancy concentration. Undoubtedly, the current results should act as a solid experiment basis for understanding the microscopic properties in GST alloy and pave the way of further application of phase change memory. Further work is also needed to clarify the atomic arrangement in GeTe–Sb2Te3 pseudobinary alloy and the origin of the migration behavior in the phase change material.

Methods

Sample preparation

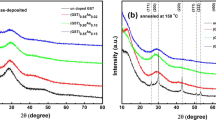

GST films (~500 nm in thickness) were directly deposited on silicon (100) substrate at room temperature by sputtering a single GST alloy target. The base pressure of the vacuum system is about 2.1 × 10−4 Pa, the Ar flow rate is 80 sccm and the corresponding sputtering pressure is about 0.31 Pa. To obtain a series of crystalline structures, the films undergone thermal annealing process from 150 to 350 °C for different times in rapid thermal processing in an argon atmosphere. By using focus ion beam (FIB) technique, the annealed films were fabricated into cross-section samples in FEI Helios 600 instrument with standard lift out and polishing process, and then cleaned in Gatan 691 PIPS at 0.8 keV for removing the residual contamination and possible damage.

Microstructure characterization

The STEM-HAADF images were captured using the STEM mode of JEM Grand ARM300F microscope with double spherical aberration (Cs) correctors, in which, the inner semi-angle for the dark field detector is larger than 63 mrad. Two windowless EDS detectors, each of which has an active area of 100 mm2, are equipped on JEM Grand ARM300F microscope, which are very close to the specimen with a high solid angle (1.7 sr). By using of the EDS detectors, the average concentrations of Ge, Sb, and Te elements of the GST films were determined to be 19.1, 24.5, and 56.4 at%, i.e., a value close to Ge2Sb2Te5. Since chalcogenide alloy is very sensitive to the accelerate electron beam, the operating voltage is under 80 kV to reduce the damage when conducting atomic EDS experiment and obtaining HAADF images, and in turn has a relatively not good enough signal–noise ratio in the results. Comparing the HAADF image before and after electron beam irradiation, no obvious artificial has been found except for a slight electron damage as shown in Supplementary Figure 1. A convergence semi-angle of 24 mrad and inner acquisition semi-angle of 63 mrad were used in STEM mode. The electron beam current is about 30 pA. The STEM probe size is around 0.08 nm which corresponds to the specified spatial resolution of the STEM instrument. All the raw data of EDS were processed with Wiener filtering which has been widely used to remove noise in HAADF images45,54,55. It has shown that no artefacts are found when comparing Wiener filtering images with raw images56 which was also confirmed in Supplementary Figure 2, implying that we can use Wiener filtering images to effectively identify the location of atomic columns, and qualitatively analyze the corresponding concentration variation in a small area, for example, the interface or the surface area of the nanostructure. Supplementary Figure 3 is a typical atomic EDS mapping result for SrTiO3 sample fitting well with the known cubic perovskite structure.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. All other relevant source data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Salinga, M. & Wuttig, M. Phase-change memories on a diet. Science 332, 543–544 (2011).

Wong, H.-S. P. & Salahuddin, S. Memory leads the way to better computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 191–194 (2015).

Rao, F. et al. Reducing the stochasticity of crystal nucleation to enable subnanosecond memory writing. Science 358, 1423–1427 (2017).

Wuttig, M. & Yamada, N. Phase-change materials for rewriteable data storage. Nat. Mater. 6, 824–832 (2007).

Yamada, N. et al. Rapid-phase transitions of GeTe–Sb2Te3 pseudobinary amorphous thin films for an optical disk memory. J. Appl. Phys. 69, 2849 (1991).

Kim, W. et al. ALD-based confined PCM with a metallic liner toward unlimited endurance. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 4.2.1–4.2.4 (2016).

Im, D. H. et al. A unified 7.5 nm dash-type confined cell for high performance PRAM device. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 1–4 (2008).

Wang, Y. et al. Scandium doped Ge2Sb2Te5 for high-speed and low-power-consumption phase change memory. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 133104 (2018).

Zhou, X. et al. Carbon-doped Ge2Sb2Te5 phase change material: a candidate for high-density phase change memory application. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 142104 (2012).

Lankhorst, M. H. R. et al. Low-cost and nanoscale non-volatile memory concept for future silicon chips. Nat. Mater. 4, 347–352 (2005).

Wang, Y. et al. Understanding the early cycling evolution behaviors for phase change memory application. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 204503 (2014).

Hegedüs, J. & Elliott, S. R. Microscopic origin of the fast crystallization ability of Ge–Sb–Te phase-change memory materials. Nat. Mater. 7, 399–405 (2008).

Li, T. et al. Carbon doping induced Ge local structure change in as-deposited Ge2Sb2Te5 film by EXAFS and Raman spectrum. AIP Adv. 8, 025201 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. RESET distribution improvement of phase change memory: the impact of Pre-programming. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 35, 536–538 (2014).

Njoroge, W. K., Wöltgens, H.-W. & Wuttig, M. Density changes upon crystallization of Ge2Sb2.04Te4.74 films. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 20, 230–233 (2001).

Cheng, H. Y. et al. A high performance phase change memory with fast switching speed and high temperature retention by engineering the GexSbyTez phase change material. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 3.4.1–3.4.4 (2011).

Park, I. M. et al. Thermomechnaical properties and mechanical stresses of Ge2Sb2Te5 films in phase-change random access memory. Thin Solid Films 517, 848–852 (2008).

Do, K. et al. TEM study on volume changes and void formation in GeSbTe fims, with repeated phase changes. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 13, H284–H286 (2010).

Simpson, R. E. et al. Interfacial phase-change memory. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 501–505 (2011).

Yamada, N. & Matsunaga, T. Structure of laser-crystallized Ge2Sb2+xTe5 sputtered thin films for use in optical memory. J. Appl. Phys. 88, 7020 (2000).

Eom, J.-H. et al. Global and local structures of the Ge–Sb–Te ternary alloy system for a phase-change memory device. Phys. Rev. B 73, 214202 (2006).

Sun, Z., Zhou, J. & Ahuja, R. Structure of phase change materials for data storage. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 055507 (2006).

He, S. et al. Metastable stacking-polymorphism in Ge2Sb2Te5. Inorg. Chem. 56, 11990–11997 (2017).

Zhang, B. et al. Vacancy structures and melting behavior in rock-salt GeSbTe. Sci. Rep. 6, 25453 (2016).

Zhang, B. et al. Element-resolved atomic structure imaging of rocksalt Ge2Sb2Te5 phase-change material. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 191902 (2016).

Kooi, B. J., Groot, W. M. G. & Hosson, J. T. M. D. In situ transmission electron microscopy study of the crystallization of Ge2Sb2Te5. J. Appl. Phys. 95, 924 (2004).

Petrov, I. I., Imamov, R. M. & Pinsker, Z. G. Electron-diffraction determination of the structures of Ge2Sb2Te5 and GeSb4Te7. Sov. Phys. Crystallogr. 13, 339–342 (1968).

Matsunaga, T., Yamada, N. & Kubota, Y. Structures of stable and metastable GeSbTe, an intermetallic compound in GeTe–Sb2Te3 pseudobinary systems. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 60, 685–691 (2004).

Yu, X. & Robertson, J. Atomic layering, intermixing and switching mechanism in Ge–Sb–Te based chalcogenide superlattices. Sci. Rep. 6, 37325 (2016).

Hernández, W. I. & Raty, J.-Y. Ab initio density functional theory study of the electronic, dynamic, and thermoelectric properties of the crystalline pseudobinary chalcogenide (GeTe)x/(Sb2Te3) (x = 1, 2, 3). Phys. Rev. B 97, 245205 (2018).

Singh, J. et al. Effect of gradual ordering of Ge/Sb atoms on chemical bonding: a proposed mechanism for the formation of crystalline Ge2Sb2Te5. J. Solid State Chem. 260, 124–131 (2018).

Da Silva, J. L. F., Walsh, A. & Lee, H. Insights into the structure of the stable and metastable (GeTe)m(Sb2Te3)n compunds. Phys. Rev. B 78, 22411 (2008).

Lee, G. & Jhi, S.-H. Ab initio studies of structural and electronic properties of the crystalline Ge2Sb2Te5. Phys. Rev. B 77, 153201 (2008).

Sosso, G. C. et al. Vibrational properties of hexagonal Ge2Sb2Te5 from first principles. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 245401 (2009).

Lotnyk, A. et al. Local atomic arrangements and lattice distortions in layered Ge–Sb–Te crystal structures. Sci. Rep. 6, 26724 (2016).

Mio, A. M. et al. Chemical and structural arrangement of the trigonal phase in GeSbTe thin films. Nanotechnology 28, 065706 (2017).

Lotnyk, A. et al. Real-space imaging of atomic arrangement and vacancy layers ordering in laser crystallised GeSbTe phase change thin films. Acta Mater. 105, 1–8 (2016).

Zhang, W., Jeong, H. S. & Song, S. A. Martensitic transformation in Ge2Sb2Te5 alloy. Adv. Eng. Mater. 10, 67–72 (2008).

Zhang, W. et al. How important is the {103} plane of stable GeSbTe for phase change memory? J. Microsc. 259, 10–15 (2015).

Park, Y. J., Lee, J. Y. & Kim, Y. T. In situ transmission electron microscopy study of the nucleation and grain growth of Ge2Sb2Te5 thin films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 252, 8102–8106 (2006).

Kim, E. T., Lee, J. Y. & Kim, Y. T. Investigation of the structural transformation behavior of Ge2Sb2Te5 thin films using high resolution electron microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 101909 (2007).

Zhang, W. et al. Role of vacancies in metal–insulator transitions of crystalline phase-change material. Nat. Mater. 11, 952–956 (2012).

Bragaglia, V. et al. Metal–insulator transition driven by vacancy ordering in GeSbTe phase change materials. Sci. Rep. 6, 23843 (2016).

Williams, D. B. & Carter, C. B. Transmission Electron Microscopy: A Textbook for Materials Science. 2nd ed., (Springer, Berlin, 2009).

Ross, U. et al. Direct imaging of crystal structure and defects in metastable GeSbTe by quantitative aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 121904 (2014).

Jiang, Y. et al. Direct atom-by-atom chemical identification of nanostructures and defects of topological insulators. Nano Lett. 13, 2851–2856 (2013).

Rao, F. et al. Direct observation of titanium-centered octahedral in titanium–antimony–tellurium phase-change material. Nat. Commun. 6, 10040 (2015).

Lotnyk, A. et al. Van der Waals interfacial bonding and intermixing in GeTe–Sb2Te3-based superlattices. Nano Res. 11, 1676–1686 (2018).

Kothleiner, G. et al. Quantitative elemental mapping at atomic resolution using X-ray spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 085501 (2014).

Lugg, N. R. et al. On the quantitativeness of EDS STEM. Ultramicroscopy 151, 150–159 (2015).

Bong-Sub, L. et al. Investigation of the optical and electronic properties of Ge2Sb2Te5 phase change material in its amorphous, cubic and hexagonal phases. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 093509 (2005).

Kalb, J., Spaepen, F. & Wuttig, M. Calorimetric measurements of phase transformations in thin films of amorphous Te alloys used for optical data storage. J. Appl. Phys. 93, 2389 (2003).

Urban, P. et al. Temperature dependent resonant X-ray diffraction of single-crystalline Ge2Sb2Te5. CrystEngComm 15, 4823–4829 (2013).

Chen, C.-C. et al. Three-dimensional imaging of dislocations in a nanoparticle at atomic resolution. Nature 496, 74–77 (2013).

Xu, R. et al. Three-dimensional coordinates of individual atoms in materials revealed by electron tomography. Nat. Mater. 14, 1099–1103 (2015).

Li, J. et al. Surface evolution of a Pt–Pd–Au electrocatalyst for stable oxygen reduction. Nat. Energy 2, 17111 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0206101), “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA09020402), and National Integrate Circuit Research Program of China (2009ZX02023-003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. and Y.W. prepared the film samples. S.L. and Y.C. conducted the FIB experiments. Y.Z., T.X., and Y.C. carried out the transmission electron microscopy experiments. Analysis of the data was mostly carried out by Y.Z., Y.W., and Y.C. with valuable suggestions from R.H., P.L., M.L., and Z.Z. Y.Z. and Y.C. wrote the paper with contributions from all co-authors. The project was initiated and conceptualized by Z.S. and S.F.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Y., Wang, Y., Xin, T. et al. Direct atomic identification of cation migration induced gradual cubic-to-hexagonal phase transition in Ge2Sb2Te5. Commun Chem 2, 13 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0114-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0114-7

This article is cited by

-

Structural Transformation of Thin Ge2Sb2Te5

Films Produced by Ion-Plasma Co-Sputtering Under Laser Irradiation Journal of Electronic Materials (2023)

-

The “gene” of reversible phase transformation of phase change materials: Octahedral motif

Nano Research (2022)

-

The effect of thickness on texture of Ge2Sb2Te5 phase-change films

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.