Abstract

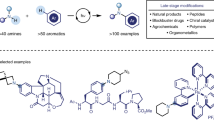

The functionalization of α-amino acids and peptides provides the opportunity to tailor the properties of these biomolecules for diverse applications in chemistry and biology. Previous methods for N-modification involve the use of aliphatic alcohols, aldehydes, or halides. Alternatively, phenolic compounds are more desirable alkylating reagents as they constitute the backbone of lignin, making them an attractive bio-renewable resource. Here we report a method to N-modify 17 out of the 20 amino acids with phenol or derivatives, with water as the sole by-product. N-arylation is achieved using 2-cyclohexen-1-one and cyclohexanone as the coupling partners. Notably, phenol is successfully used to N-cyclohexylate α-amino acids and small peptides in excellent yields under bio-compatible conditions without racemization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amino acids are bio-renewable, C-chiral, nitrogen-containing feedstocks with a plethora of different applications. In addition to their biological function as protein building blocks, amino acids serve different purposes within organic chemistry. Due to their inherent chirality they may function as organocatalysts1,2,3, ligands4, and as structural backbones in pharmaceuticals5,6 and agrochemicals5,7,8. The N-terminus is a ubiquitous and practical handle, which can be used to introduce diverse functional groups that can significantly alter the amino acid’s physiological and pharmacological activities9,10, especially when incorporated into peptides11. In addition, these modifications can facilitate the characterization of the N-terminal amino acid by adding fluorescent labels for easy identification by light absorbing methods9, or in a peptide chain by mass spectrometry12.

Amino acids are challenging substrates for coupling reactions due to their low nucleophilicity, pH sensitivity, and the broad range of reactive functionalities at the α-position. Despite these challenges, the N-arylation of amino acids has been achieved using the classical Ullmann13,14 and the Buchwald-Hartwig coupling reactions15. Amino acid N-mono-alkylation has often been attained by reductive amination using boron or transition metal complexes as the reducing agents16,17, and most recently through hydrogen borrowing strategies enabling the use of aliphatic alcohols as the alkylating reagents18,19. Despite the versatility of these methods some challenges such as the use of organic halides, low selectivity and high temperatures remain to be addressed.

Previously, our group reported the use of phenols and 2-cyclohexen-1-one as precursors to N-alkylated20,21 and N-arylated22,23,24 amines. Phenols, in particular, are one of the most abundant aromatic feedstocks on the planet, both from the coal-based industry and as the core structure in lignins25. In addition, via controlled hydrogenation, phenols can be transformed into cyclohexanones26, switching them to readily modifiable structures through nucleophilic addition. Vice versa, by dehydrogenating cyclohexanone, a phenolic core can be re-obtained27. This ability to tune a structure so finely has led to significant progress in the development of chemical reactions. Based on our previous work, and inspired by the possibility of modifying amino acids using naturally abundant sources, we began to investigate the possibility of using 2-cyclohexen-1-one and phenols as reagents for N-terminal modification under biocompatible conditions.

Here we report the successful N-modification of amino acids using phenols and cyclohexenones (Fig. 1). Upon optimization we found that N-arylation is achieved using 2-cyclohexen-1-one and cyclohexanone as the coupling partners with up to 74% yield, while phenol is successfully used to N-cyclohexylate 17 out of the 20 natural α-amino acids as well as small peptides in excellent yields under bio-compatible conditions without racemization.

Results

Amino acid N-arylation with 2-cyclohexen-1-one and cyclohexanone

We began by investigating the N-arylation of glycine methyl ester (1) as the model substrate for the reaction (Fig. 2). The hydrochloride salt was chosen because amino esters have a higher stability as salts since the formation of 2,5-diketopiperazines (dimerization product) is no longer feasible. Using amino acids in their free carboxylic acid form resulted in decomposition of the starting materials under the reaction conditions due to decarboxylation. The transformation was initially tested using palladium on carbon with a 10 mol% Pd loading in toluene under an argon atmosphere, and an excess amount of 2-cyclohexen-1-one (2) to facilitate nucleophilic addition. The desired product 3 was obtained in 47% yield, accompanied by a 20% yield of the N-cyclohexylated product 4 (Table 1, entry 1). Different bases were added to the reaction in 50 mol% loading with the aim of favouring imine formation (Table 1, entries 2-6). CaCO3 gave the best results, yielding 63% of 3, and 15% of 4 (Table 1, entry 6). Increasing the quantity of base resulted in loss of activity (Table 1, entry 7). This fine tuning of the pH is required to free enough amino acid from its hydrochloric salt form, while leaving enough acid to allow for the subsequent imine formation. The formation of compound 4 was investigated by kinetic studies (Supplementary Figure 1). We concluded that 4 is obtained from the hydrogenation of product 3 and, once formed, slowly decomposes over time. Thus, running the reaction under an atmosphere of oxygen was investigated to accelerate the release of H2 being adsorbed onto the catalyst’s surface28. This led to a 64% yield of 3 and a decrease in the formation of 4–8%. Traces of the biarylated product 5 were also detected. Formation of product 5 indicated an increase in catalytic activity of the system (Table 1, entry 8). This result prompted us to investigate lower amounts of base in the system, with 20 mol% of CaCO3 proving optimal for the formation of 3 in 69% yield (Table 1, entry 10). Further kinetic studies (Supplementary Table 1) showed that the reaction was completed within 4 h, giving the desired product 3 in a 74% yield (Table 1, entry 11). For the effect of different palladium catalysts see supporting information (Supplementary Table 2). While previous work in our group regarding the arylation of secondary amines used Pd (II) as the catalyst23, we have only achieved arylation of primary amines using heterogeneous Pd (0) catalysts22. We reasoned that this might be due to primary amines readily coordinating to the Pd (II) heterogeneous catalysts, which might lead to decomposition of the starting material by β-hydride elimination. Different supports were also tested, Lewis acidic and basic supports did not improve the reaction yield.

With the optimized conditions in hand, various amino acids and cyclohexenones were tested as substrates (Fig. 3). Overall, amino acids with aliphatic R1 chains gave the best reaction yields. Glycine tert-butyl ester afforded the product 3a in 25% yield. The lower yield, compared to glycine methyl ester, might be the result of the tert-butyl group being cleaved under the reaction conditions, leading to de-carboxylation of the starting material. β-Alanine gave a lower product yield of 3b, which might be a result of the increased basicity at the N–H group, rendering it more likely to stay protonated under the reaction conditions. Amino acids can racemize following the formation of the Schiff base as the α-proton can be abstracted from the pseudo-anhydride imine intermediate, see supporting information (Supplementary Figure 2) for a proposed mechanism based on previous mechanistic studies21,26. The enantiomeric retention of products 3c (52% ee), 3d (97% ee), and 3e (100% ee) indicates that the substitution and steric hinderance at the α-position can impact the rate in which the acid-base equilibrates, leading to improved enantiomeric retention. Tert-butyl protected serine (Fig. 3, product 3i) gave higher yields compared to other heteroatom-containing amino acids. Deprotected or benzyl protected serine led to decomposition of the starting material. Amino acids with aromatic R1 chains (phenylglycine, phenylalanine and tyrosine) gave poor yields (3j–3l), as dearomatization of the R1 chain was also obtained as a side product. The cyclohexenone scope proved to be more limited (products 3m–3o). Based on previous work by our group, we anticipated that sterics and electronics would have strong effects23, an effect which seemed to be enhanced when using less nucleophilic amines, since imine formation happens more reluctantly.

Amino acid and cyclohexenone substrate scope for the N-arylation reaction. Reaction conditions: 1, 1a-1k (0.24 mmol, 1 equiv.), 2, 2l-2n (0.48 mmol, 2 equiv.), Pd/C (5 wt%, 0.48 mmol), CaCO3 (0.048 mmol, 0.2 equiv.), O2saturated toluene (1 mL), 140 °C. [a] 50 mol% of CaCO3 was used. Modified reaction times are shown in parenthesis.[b]O-tBu tyrosine methyl ester •HCl was used as starting material

In parallel, cylohexanone (6) was tested as a possible substrate, based on the fact that 2-cyclohexen-1-one has the potential to be reduced during the reaction process (Fig. 4). Under the optimized conditions (Table 2, entry 1), the formation of biarylated product 5 was obtained in higher yields than when 2-cyclohexen-1-one was used as the substrate. Upon increasing the catalyst loading to 20 mol%, the base to 5.0 equiv., and running the reaction for 24 h, biarylated product 5 was obtained in 65% yield (Table 2, entry 2). We propose that the requirement for a higher loading of Pd/C is because an oxide shell forms on palladium throughout the reaction as was observed by XPS (see supporting information, Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Figures 3-5). When 2-cyclohexen-1-one (2) was tested under the latter conditions, 55% yield of product 5 was obtained.

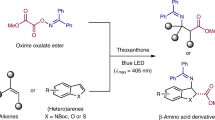

Amino acid N-cyclohexylation with phenol

Given the harsh conditions required for the re-aromatization reaction, we envisioned favoring the formation of the reduced product under milder conditions. Previously, our group[20] and that of Vaccaro29 had shown the feasibility of cyclohexylating amines in water, encouraging us to develop an applicable methodology for all amino acids and peptides under bio-compatible conditions. We used glycine as the model substrate at room temperature in water, with phenol as the coupling reagent and palladium on carbon as the catalyst (Fig. 5). Using 2 equivalents of HCO2Na with respect to phenol, produced the desired product in 11% yield (Table 3, entry 1), and by increasing the loading to 4 equivalents the yield drastically improved to 96% (Table 3, entry 2). Further increasing the loading to 6 equivalents gave a quantitative yield (Table 3, entry 3). Attempts to reduce the amount of phenol (Table 3, entry 4) or Pd/C (Table 3, entry 5) resulted in lower yields of N-cyclohexylglycine (9). Nonetheless, we were pleasantly surprised to find that the Pd/C catalyst could be recovered and reused for up to three cycles upon filtration, before a decrease in activity was observed (Table 3, entries 6–8). Using hydrogen or sodium borohydride as the reducing agents (Table 3, entries 9–10) significantly decreased the efficiency of the reaction.

We tested cyclohexanol, cyclohexanone, and 2-cyclohexen-1-one as coupling partners under the optimized conditions (Fig. 6). As suspected, the alcohol was the only species unsuitable for the transformation since imine formation cannot proceed. Only the mono N-cyclohexylation was observed when using both cyclohexanone and 2-cyclohexen-1-one. These results strongly suggest that phenol is reduced in-situ to a ketone, aminated, and further reduced to yield product 926.

The reaction scope was investigated under the optimized conditions, proving to be efficient in the N-cyclohexylation of 17 out of the 20 naturally occurring amino acids without protecting groups (Fig. 7). Sulfur containing compounds deactivated the palladium catalyst, making them inaccessible substrates for this methodology. Amino acids with non-polar, aliphatic R1 chains, including β-alanine (9, 9a–9d), as well as those with polar uncharged (9e–9i), aromatic (9j–9l), and polar charged R1 chains (9m–9q) were excellent substrates for the reaction and showed that functional groups such as alcohols, carboxylic acids, and amides were compatible. In the case of O-unprotected tyrosine (9k), the phenol ring was also reduced, but no side reactions were observed. By using OtBu-Tyr (3k), this problem was circumvented, and aromaticity was maintained. Lysine resulted in the doubly N-cyclohexylated product (9o), requiring that double the equivalents of phenol be added. Some substrates required the use of gentle heating at 50 °C, or the addition of methanol to the reaction solvent to solubilize the substrate in water. Given our success, we were set to test more challenging substrates such as di-, tri-, and tetra- peptides which, if necessary, could be later on conjugated to longer amino acid chains through traditional coupling processes. Glycine peptide chains were chosen as model substrates and were succesfully N-cyclohexylated (9r–9t) with solubility being the only limitation to the process. The solubility of these peptides can be readily tuned by modifiying the different substituents in the R1 chains, making this an efficient procedure for their N-modification. Finally, various phenolic compounds were examined as coupling partners, with para-substitued compounds being well tolerated (9u–9x), and di-substituted phenols leading to a lower yield due to steric effects (9 y). When para-chloro phenol (8z) was used as the substrate, the product with the cleaved chlorine group was obtained in quantitative yields, consistent with previous reports29. To test for enantiomeric retention we selected product 9j since the α-proton could easily racemize due to its benzylic position. In addition, the reaction for phenylalanine (7j) was performed at 50 °C, making the conditions harsher than for most of the substrates. Upon running the reaction under the described conditions, we found that the N-cyclohexylated product 9j was generated without any racemization.

Amino acid and phenolic substrate scope for the N-cyclohexylation reaction. Reaction conditions: 7, 7a-7t (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv.), 8, 8u-8y (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), HCO2Na (1.8 mmol, 6 equiv.), Pd/C (10 wt%, 0.2 mmol), H2O (1mL), 24 h, rt. [a] Temperature increased to 50 °C to improve solubility. [b] 1 mL of a 1:1 MeOH:H2O mixture was usedas the solvent. [c] 1 mmol of starting material used in 0.3 mL of 20% MeOH in H2O

Discussion

Bio-renewable feedstocks were successfully used to synthesize N-modified amino acids with phenols as the alkylation reagents and Pd/C as the catalyst. The N-arylation requires high temperatures due to the high energy required to aromatize the cyclohexyl ring. Nevertheless, the N-cyclohexylation was successfully achieved for 17 out of the 20 naturally occurring amino acids under bio-compatible conditions without racemization. With these techniques in hand, we hope that we can move towards the use of more sustainable feedstocks for the modification of bio-compounds with applications in chemical biology, pharmaceuticals, and agrochemicals.

Methods

Amino acid N-arylation

In an acid washed, flame dried, U-shaped microwave vial, charged with a stir bar; the amino acid (0.24 mmol, 1equiv.), CaCO3 (4.8 mg, 0.048 mmol, 0.2 equiv.), and the dried Pd/C (5 wt%) (0.48 mmol, 51.1 mg) were added under air. The vial was flushed with oxygen three times and 1 mL of dry, oxygen saturated toluene was then added under an oxygen flow. 2-Cyclohexen-1-one (0.48 mmol, 47 µL) was finally added to the vial via syringe. The vial was capped with a Teflon-lined septa fitted within an aluminum crimp cap and was submerged in a preheated oil bath at 140 °C with stirring at 500 rpm for the indicated time. The reaction was then lifted from the oil bath and left to cool down to room temperature without interrupting the stirring. The aluminum cap was removed, and the reaction was diluted using ethyl acetate. The Pd/C was then removed by filtration through celite, washing with additional ethyl acetate. Solvent was removed in vacuo and residue was purified by preparatory TLC on silica gel. See Supplementary Notes 1–3 for comments on catalyst activation, toluene O2 saturation and reproducibility.

Amino acid N-cyclohexylation

In a U-shaped microwave vial, charged with a stir bar, the amino acid (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv.), phenol (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), HCO2Na (1.8 mmol, 6 equiv.), and Pd/C (10 wt%) (0.2 mmol, 25.5 mg) were added under air. The vial was flushed with argon three times and 1 mL of distilled water was then added under an argon flow. The vial was capped with a rubber septum and stirring was set at 500 rpm for 24 h at the indicated temperature. The septum was then removed and the reaction was diluted using distilled water. The Pd/C was then removed by filtration through celite, washing with additional water and methanol. Reaction was acidified to pH = 0 with HCl to be able to remove formic acid in vacuo. The reaction mixture was then neutralized, concentrated in vacuo and filtered with cold methanol, to remove NaCl, in order to obtain the pure product.

Materials and experimental procedures

See Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Notes 1–3.

Kinetic studies

See Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1.

Reaction optimization

See Supplementary Table 2.

Catalyst characterization

See Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Figures 3–5.

Characterization of products

See Supplementary Figures 6–16 for HPLC chromatograms and Supplementary Figures 17–101 for NMR spectra.

Data availability

We declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information file, or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Xie, H., Hayes, T. & Gathergood, N. in Amino Acids, Peptides and Proteins in Organic Chemistry. 281–337 Weinheim, Germany (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, 2009).

Xu, L.-W. & Lu, Y. in Comprehensive Enantioselective Organocatalysis: Catalysts, Reactions, and Applications. Vol. 1. 51–68 Weinheim, Germany (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, 2013).

Zhao, X., Zhu, B. & Jiang, Z. Acyclic amino acid based bifunctional chiral tertiary amines, quaternary ammoniums and iminophosphoranes as organocatalysts. Synlett 26, 2216–2230 (2015).

Zhang, F.-L., Hong, K., Li, T.-J., Park, H. & Yu, J.-Q. Functionalization of C(sp3)–H bonds using a transient directing group. Science 351, 252–256 (2016).

Drauz, K. et al. in Ullmann’s Fine Chemicals. Vol. 1. 165–222 Weinheim, Germany (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, 2014).

Mendez-Samperio, P. Peptidomimetics as a new generation of antimicrobial agents: current progress. Infect. Drug Resist. 7, 229–237 (2014).

Zhao, J. et al. Application of α-amino acids in agrochemicals synthesis. Nongyaoxue Xuebao 12, 371–382 (2010).

Lamberth, C. Amino acid chemistry in crop protection. Tetrahedron 66, 7239–7256 (2010).

Geoghegan, K. F. Modification of amino groups. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 86, 15.2.1‐15.2.20 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/cpps.17

Park, J. D. & Kim, D. H. Cysteine Derivatives as Inhibitors for Carboxypeptidase A: synthesis and structure−activity relationships. J. Med. Chem. 45, 911–918 (2002).

Liu, W. X. & Wang, R. Endomorphins: potential roles and therapeutic indications in the development of opioid peptide analgesic drugs. Med. Res. Rev. 32, 536–580 (2012).

Takashi, N. Chemistry in proteomics: an interplay between classical methods in chemical modification of proteins and mass spectrometry at the cutting edge. Curr. Proteom. 3, 33–54 (2006).

Sharma, K. K., Sharma, S., Kudwal, A. & Jain, R. Room temperature N-arylation of amino acids and peptides using copper(i) and [small beta]-diketone. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13, 4637–4641 (2015).

Sharma, K. K., Mandloi, M., Rai, N. & Jain, R. Copper-catalyzed N-(hetero)arylation of amino acids in water. RSC Adv. 6, 96762–96767 (2016).

King, S. M. & Buchwald, S. L. Development of a method for the N-arylation of amino acid esters with aryl triflates. Org. Lett. 18, 4128–4131 (2016).

Baxter, E. W., Reitz, A. B. Reductive Aminations of Carbonyl Compounds with Borohydride and Borane Reducing Agents. Org. React. 59, 1-714 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1002/0471264180.or059.01

Song, Y. et al. A simple method for preparation of N-mono- and N,N-di-alkylated α-amino acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 41, 8225–8230 (2000).

Xu, C.-P., Xiao, Z.-H., Zhuo, B.-Q., Wang, Y.-H. & Huang, P.-Q. Efficient and chemoselective alkylation of amines/amino acids using alcohols as alkylating reagents under mild conditions. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 46, 7834–7836 (2010).

Yan, T., Feringa, B. L. & Barta, K. Direct N-alkylation of unprotected amino acids with alcohols. Sci. Adv. 3, EAAO6494 (2017).

Chen, Z., Zeng, H., Gong, H., Wang, H. & Li, C.-J. Palladium-catalyzed reductive coupling of phenols with anilines and amines: efficient conversion of phenolic lignin model monomers and analogues to cyclohexylamines. Chem. Sci. 6, 4174–4178 (2015).

Qiu, Z., Li, J.-S. & Li, C.-J. Formal aromaticity transfer for palladium-catalyzed coupling between phenols and pyrrolidines/indolines. Chem. Sci. 8, 6954–6958 (2017).

Chen, Z. et al. Formal direct cross-coupling of phenols with amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14487–14491 (2015).

Girard, S. A. et al. Pd-catalyzed synthesis of aryl amines via oxidative aromatization of cyclic ketones and amines with molecular oxygen. Org. Lett. 14, 5606–5609 (2012).

Li, J.-S., Qiu, Z. & Li, C.-J. Palladium-catalyzed synthesis of N-cyclohexyl anilines from phenols with hydrazine or hydroxylamine via N-N/O cleavage. Adv. Synth. Catal. 359, 3648–3653 (2017).

Zeng, H. et al. An adventure in sustainable cross-coupling of phenols and derivatives via carbon–oxygen bond cleavage. ACS Catal. 7, 510–519 (2017).

Liu, H., Jiang, T., Han, B., Liang, S. & Zhou, Y. Selective phenol hydrogenation to cyclohexanone over a dual supported Pd–lewis acid catalyst. Science 326, 1250–1252 (2009).

Iosub, A. V. & Stahl, S. S. Palladium-catalyzed aerobic dehydrogenation of cyclic hydrocarbons for the synthesis of substituted aromatics and other unsaturated products. ACS Catal. 6, 8201–8213 (2016).

Choudhary, V. R. & Samanta, C. Role of chloride or bromide anions and protons for promoting the selective oxidation of H2 by O2 to H2O2 over supported Pd catalysts in an aqueous medium. J. Catal. 238, 28–38 (2006).

Jumde, V. R. et al. Domino hydrogenation–reductive amination of phenols, a simple process to access substituted cyclohexylamines. Org. Lett. 17, 3990–3993 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Canada Research Chair Foundation (to C.J.L.), the CFI, FQRNT Center for Green Chemistry and Catalysis, NSERC and McGill University for financial support. The authors thank Z. Hearne, W. Liu, Z. Qiu and R. Barrett for proofreading, and thank A. Li for his expertize in XPS spectroscopy. A.D.-H. thanks CONACYT for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Project conceptualization by C.-J.L.; methodology by A.D.-H.; experimentation and characterization by A.D.-H. and I.P.; resources by C.-J.L.; writing – original draft by A.D.-H.; writing – review & editing by I.P. and C.-J.L.; supervision by C.-J.L.; funding acquisition by C.-J.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dominguez-Huerta, A., Perepichka, I. & Li, CJ. Catalytic N-modification of α-amino acids and small peptides with phenol under bio-compatible conditions. Commun Chem 1, 45 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-018-0042-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-018-0042-y

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.