Abstract

Intrinsic cardiac adrenergic (ICA) cells regulate both developing and adult cardiac physiological and pathological processes. However, the role of ICA cells in septic cardiomyopathy is unknown. Here we show that norepinephrine (NE) secretion from ICA cells is increased through activation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) to aggravate myocardial TNF-α production and dysfunction by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). In ICA cells, LPS activated TLR4-MyD88/TRIF-AP-1 signaling that promoted NE biosynthesis through expression of tyrosine hydroxylase, but did not trigger TNF-α production due to impairment of p65 translocation. In a co-culture consisting of LPS-treated ICA cells and cardiomyocytes, the upregulation and secretion of NE from ICA cells activated cardiomyocyte β1-adrenergic receptor driving Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) to crosstalk with NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Importantly, blockade of ICA cell-derived NE prevented LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction. Our findings suggest that ICA cells may be a potential therapeutic target for septic cardiomyopathy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myocardial dysfunction is a frequent event that correlates with the severity of sepsis, which accounts for the primary cause of death in intensive care units1,2. During sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction (SIMD), pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), interact with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on immune and cardiac cells, activating NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascades to produce proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, interleukin-1β and interleukin-6. These cytokines act on endothelial cells, cardiac fibroblasts, and cardiomyocytes to increase the production of inflammatory mediators, which cause myocardial depression3,4,5,6,7,8. Norepinephrine (NE), demonstrated to be associated with SIMD9,10, can activate β1-adrenergic receptor (AR) and promote Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) phosphorylation, IκBα phosphorylation, and TNF-α expression, all of which contribute to cardiomyocyte apoptosis in septic mice11. Moreover, selective β1-AR blockade improves cardiac function and survival in septic patients12,13.

The intrinsic cardiac adrenergic (ICA) cells, which express tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH) necessary for catecholamine biosynthesis, have been identified in the mammalian heart as an important origin of intrinsic cardiac catecholamines14,15. A growing body of literature has suggested that the ICA system is a critical regulator of mammalian heart development, post-heart transplantation inotropic support, and cardioprotection during ischemia/reperfusion15,16,17,18,19,20,21. However, the response of ICA cells in SIMD is unclear. Our previous study showed that blockade of β1-AR suppressed LPS-induced TNF-α production in primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes cultured by traditional methods in the absence of exogenous NE22, indicating that some β1-AR stimuli function in the culture. In addition, ICA cells were found to be present in the primary neonatal rat cardiomyocyte culture using traditional methods14,23. In this context, we postulated that LPS might stimulate ICA cells to synthesize NE that would promote LPS-induced cardiomyocyte TNF-α production and myocardial dysfunction via β1-AR.

In this study, we investigate the effect of LPS on NE production in ICA cells and the role of ICA cell-derived NE in LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction. We demonstrate that LPS increases NE production in ICA cells that express TLR4, and identify ICA cell-derived NE as a paracrine signal to enhance LPS-provoked proinflammatory response in cardiomyocytes and myocardial dysfunction via β1-AR-CaMKII-NF-κB/MAPKs signaling cascades.

Results

ICA cells are present in neonatal and adult rat hearts

Immunoreactivity of TH, a key catecholamine-forming enzyme, in ICA cells has been demonstrated previously (Fig. S1B)19, and the established 3D structure of ICA cells illustrated its TH immunoreactivity (Fig. S1C). We thus performed immunofluorescent staining of TH to identify ICA cells. As shown in Fig. 1a, in the culture of cardiomyocytes isolated from neonatal rat hearts using a traditional enzymatic method24, the TH-positive ICA cells were found to cluster nearby cardiac troponin I (cTn I)-positive neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVM). In addition, these ICA cells were also found in adult rat hearts by staining of TH and cTn I in tissue slices (Fig. 1b, white arrow). Macrophages were reported as a source of catecholamines in response to acute inflammatory injury25, but we demonstrated that ICA cells did not express macrophage markers CD68 or F4/80 (Fig. 1c and Fig. S1D, E). Moreover, single-cell RNA sequencing revealed that ICA cells (present Dbh and Ddc coding for Dopa Decarboxylase) and macrophages (present Cd68, Msr1, and Adgre1 coding for F4/80) were in two distinct clusters (Fig. 1d). Therefore, ICA cells were not considered to be of the macrophage lineage. Since vimentins are type III intermediate filaments expressed especially in mesenchymal cells, co-staining of vimentin, cTn I, and TH in co-culture of ICA cells and cardiomyocytes suggested that ICA cells are of mesenchymal cell origin (Fig. 1e). To validate the specificity of each staining, negative controls are provided in Fig. S2.

a Immunofluorescent staining of primary cardiomyocytes and ICA cells isolated from neonatal rat hearts using traditional method (n = 6). b Immunofluorescent staining of adult rat cardiac tissue slides (n = 3). cTn I (cardiac troponin I): cardiomyocytes, red; TH (tyrosine hydroxylase): ICA cells, green (white arrow). c ICA cells identified using macrophage markers, TH: ICA cell, green; CD68: marker of macrophage, red; F4/80: marker of macrophage, magenta (n = 6). d Single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis of cardiac cells obtained using the Percol method. Note, both ICA cells and macrophages are identified as two different clusters. Dbh codes Dopamine Beta-Hydroxylase, Ddc codes Dopa Decarboxylase, Cd68 codes CD68, Adgre1 codes F4/80, and Msr1 codes MSR1 (n = 24). e Immunostaining of ICA cells and cardiomyocyte, cTn I: cardiomyocyte, red; TH: ICA cells, green; Vimentin: marker of mesenchymal cells, magenta (n = 6). Nuclei of cells in all groups were dyed using DAPI: blue. The data represent two independent experiments, n represents the number of neonatal rats (a, c, and d) or adult rats (b).

Increased NE release from ICA cells promotes cardiomyocyte TNF-α production in response to LPS challenge

The primary NRVM culture containing ICA cells is defined as a co-culture of ICA cell and NRVM (NRVM ICA cell+). To analyze the role of ICA cells, we used an established method of superparamagnetic iron oxide particles (SIOP) to obtain pure NRVM that contains no ICA cells (NRVM ICA cell−) (Fig. 2a)24. LPS significantly raised NE levels in the supernatants of NRVM ICA cell+ with either different doses of LPS (LPS 0.01 μg/mL, 0.1 μg/mL, and 1 μg/mL) or different treatment durations (LPS 0, 6, and 12 h) when compared with controls (Fig. 2b). During the Langendorff perfusion of adult rat hearts, LPS elicited negligible influences on NE levels in perfusate, suggesting that circulating NE was not involved due to the lack of sympathetic nerves and the adrenal medulla in the Langendorff model (Fig. 2c). However, LPS administration significantly increased the level of NE in myocardial homogenate (Fig. 2d). Immunostaining confirmed that macrophages were not present in the current cardiomyocyte culture system (Fig. 2e), and single-cell RNA sequencing demonstrated that Dbh was not induced in LPS-treated Cd68 positive macrophages, which was expressed in ICA cells (Fig. 2f). Therefore, the increase of NE level in NRVM ICA cell+ culture conditions and adult rat myocardial homogenate could be attributed to the ICA cells, but not macrophages. Consequently, we found that blockade of β1-AR using CGP20712A, a selective β1-AR antagonist, dramatically suppressed LPS-induced TNF-α production in NRVM ICA cell+, whilst removal of ICA cells abolished the impact of CGP20712A on TNF-α production (Fig. 2g). Moreover, the removal of ICA cells caused a lower level of TNF-α in the supernatants of LPS-stimulated NRVM ICA cell− than that of NRVM ICA cell+ (Fig. 2h). These data support the concept that LPS stimulates ICA cell-derived NE release, which promotes LPS-induced TNF-α production in cardiomyocytes.

a Immunofluorescent staining of neonatal rat ventricular myocyte (NRVM) co-culturing with ICA cells (NRVM ICA cell+) and NRVM without ICA cells (NRVM ICA cell−), cTn I: cardiomyocytes, red; TH: ICA cells, green; DAPI: nuclei, blue (n = 12). b Norepinephrine (NE) level in supernatants of NRVM ICA cell+ stimulated with different doses of LPS for 6 h, and with 1 µg/mL LPS for different durations (n = 36, each dot represents one independent repeat). c NE in perfusate from Langendorff-perfused adult rat hearts, control: K-H buffer. d NE in myocardial homogenates from adult rat hearts Langendorff perfused for 140 min, control: K-H buffer (n = 7 rats per group in c and d, each dot represents an adult rat). e Immunostaining of cells in current cardiomyocyte culture, CD68: marker of macrophage, red; TH: maker of ICA cells, green (n = 6). f Single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis of cardiac cells obtained using the Percol method, containing both ICA cells and macrophages treated with LPS. Dbh codes Dopamine Beta-Hydroxylase, Cd68 codes CD68 (n = 24). g TNF-α in supernatants 6 h post LPS-treated NRVM ICA cell+ and NRVM ICA cell- pretreated with 2 µM CGP20712A for 30 min prior to LPS. h TNF-α in supernatants of NRVM ICA cell+ and NRVM ICA cell− stimulated with 1 µg/mL LPS for 6 h (n = 36, each dot represents one independent repeat in g and h). Data are presented as mean ± SEM, the P-values were assigned on each panel. b the LPS dose data were analyzed using non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s method of comparison, the duration data and g and h were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparison test; c multiple t-test followed by the Holm-Sidak method; d independent Student’s t-test. The in vitro data represent three independent experiments. n represents the number of neonatal rats (a, b, e–h) or adult rats (c, d).

LPS upregulates NE-producing enzyme expression in ICA cells

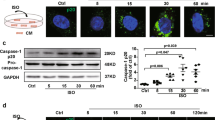

We next intended to elucidate how NE release is increased following LPS treatment. Given TH and DBH are the key enzymes responsible for NE biosynthesis9, we evaluated the expression of TH and DBH in ICA cells. Immuno-staining showed that LPS significantly stimulated TH expression in neonatal and adult rat ICA cells (Fig. 3a, b). In the NRVM ICA cell+ culture, LPS (1 μg/mL) stimulation for 6 h and 12 h dramatically increased TH and DBH mRNA expression, and different doses of LPS also significantly enhanced TH and DBH mRNA expression after 6 h compared to controls (Fig. 3c). Consistently, a dramatic increase was observed in the protein expression of TH and DPH following LPS treatment (Fig. 3d, e). In Langendorff-perfused adult rat hearts, LPS increased TH and DBH expression significantly at both mRNA and protein levels compared to controls (Fig. 3f, g). These data show that LPS increases NE release by upregulating TH and DBH expression in ICA cells.

a and b TH expression in NRVM ICA cell+ treated with saline or LPS for 6 h (a, n = 6) and adult rat hearts Lagendorff perfused for 2 h (b, n = 6 per group); cTn I: cardiomyocytes, red; TH: ICA cells, green; DAPI: nuclei, blue. c–e mRNA and protein expression of TH and DBH relative to GAPDH in NRVM ICA cell+ stimulated with LPS at different time points and doses (n = 36, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparison test, each dot represents one independent repeat). f and g mRNA and protein expression of TH and DBH relative to GAPDH in myocardium from adult rat hearts Lagendorff perfused for 2 h, control: K-H buffer, LPS: 1.5 µg/mL in K-H buffer (n = 6 rats per group, independent Student’s t-test, each dot represents a rat). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P-values were assigned on each panel. n represents the number of neonatal rats (a–e) or adult rats (f–g).

LPS increases TH and DBH biosynthesis through TLR4-MyD88/TRIF-AP-1 signaling

We next attempted to pinpoint the underlying mechanism of NE-producing enzyme upregulation in ICA cells stimulated by LPS. Since TLR4 is a well-known receptor of LPS26, we thus hypothesized that TLR4 activation mediates LPS-induced expression of TH and DBH in ICA cells. To this end, we employed immuno-staining to examine the expression of TLR4 in ICA cells. Cardiomyocytes were included as a positive control on which TLR4 expression has been demonstrated27. Immuno-staining of TLR4 in NRVM ICA cell+ and isolated ICA cells showed that ICA cells (as well as cardiomyocytes) expressed TLR4 (Fig. 4a and Fig. S4A). Blockade of TLR4 signaling using the Viper peptide (a blocker of TLR4)28 markedly suppressed LPS-induced NE production as well as expression of TH and DBH in ICA cells (Fig. 4b, c). Consistently, the DBH expression and NE production were not LPS inducible in TLR4-deficient (Tlr4Lps-del) NMVM ICA cell+, and lower than those in LPS-treated wild-type controls (Fig. 4d–f). Furthermore, we cloned the rat TH promoter into a luciferase reporter (Fig. S4B–F), and found that LPS stimulation markedly activated the TH promoter as well as the AP-1 promoter (Fig. 4g). Similarly, overexpression of the TLR4 adaptors, MyD88 and TRIF, significantly activated both the TH and the AP-1 promoters (Fig. 4h and Fig. S4H). Of note, AP-1 is a heterodimer composed of proteins belonging to the c-Jun and c-Fos families that have specific binding sites on the TH promoter29. To see whether disruption of AP-1 binding impacts TH promoter activation, we knocked down c-Jun and c-Fos using the siRNAs in HEK293/hTLR4-HA cells (Fig. 4i, Fig. S5). The activation of the TH promoter in response to MyD88 overexpression was dramatically suppressed by c-Jun siRNA and c-Fos siRNA (Fig. 4j). In addition, single-cell RNA sequencing verified that LPS induced increased Jun expression in ICA cells (Fig. 5h). These results reveal LPS induces NE enzyme biosynthesis via TLR4-MyD88/TRIF-AP1, which leads to activation of the TH promoter.

a Co-immunofluorescent staining of TLR4 and TH in NRVM ICA cell+, TLR4: toll-like receptor 4, red; TH: ICA cells, green; DAPI: nuclei, blue (n = 6). b and c NE production as well as TH and DBH expression in rat ICA cells treated with Viper (TLR4 inhibitor, 10 μM) for 2 h prior to LPS for 6 h. (n = 48, each dot represents one independent repeat). d TLR4 expression in wildtype (WT) and TLR4-deficient (Tlr4Lps-del) NMVM ICA cell+. e and f NE production and DBH expression in WT and Tlr4Lps-del NMVM ICA cell+ stimulated with LPS for 6 h, control: saline (n = 12, each dot represents a biological replicate in d–f). g Luciferase activity of AP-1-luc- and TH-promoter-luc- relative to RLTK-luc- in HEK293/hTLR4 cells at 36 h after transfection and LPS stimulation. h Luciferase activity of AP-1-luc- and TH-promoter-luc- relative to RLTK-luc- in HEK293/hTLR4 cells at 24 h after transfection with plasmids (0.1 μg/mL) encoding MyD88 and TRIF. i Expression of c-Jun and c-Fos in HEK293/hTLR4 cells at 24 h after transfection with MyD88 plasmid, c-Jun siRNA and c-Fos siRNA. j Luciferase activity of TH-promoter-luc- relative to RLTK-luc- in HEK293/hTLR4 cells at 24 h after transfection with MyD88 plasmid, c-Jun siRNA, and c-Fos siRNA, (0.1 μg/mL for plasmid) (each dot represents one independent repeat in (g–j)). Data are presented as mean ± SEM using one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparison test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, most of the P-values were assigned on the figure. n represents the number of neonatal rats (a–c) or neonatal mice (d–f).

a Immunofluorescent-staining of TNF-α in NRVM ICA cell+ stimulated with 1 µg/mL LPS for 6 h, cTn I: cardiomyocytes, red; TH: ICA cell (white arrow), green; TNF-α, yellow; DAPI: nuclei, blue (n = 12 neonatal rats). b Schematic of single-cell RNA-sequencing experimental strategy. c t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) projection of cardiac cells, batch effect analysis between control and LPS groups, control: saline, 24,210 cells. d t-SNE map of cardiac cells, different colored clusters represent distinct populations, 24,210 cells. e ICA cells expressing Dbh and macrophages expressing Cd68 are separated in two clusters, 24,210 cells. f and g Analysis of substructure in ICA and cardiomyocyte cluster indicates subcluster 3 (Purple) is a ICA cell subpopulation, 1765 cells. h Expression of Dbh and Jun in ICA cells between control and LPS groups, and Tnf gene expression in ICA cells and macrophages between control and LPS groups, 138 cells. i Expression of Tnf, Il6, and Il1b in macrophages between control and LPS groups, 572 cells. j Top 11 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) which include Nfkbia in the ICA subcluster between control and LPS groups, control: saline, 138 cells. k Expression of Tnfaip6 and Nfkbia in ICA cells between control and LPS groups, 138 cells. l Immunofluorescent-staining of p65 localization in NRVM ICA cell+ stimulated with saline or 1 µg/mL LPS for 6 h, p65, red; TH: ICA cells, green; DAPI: nuclei, blue (n = 6 neonatal rats). For single-cell transcriptomes (b–j), n = 24 neonatal rats. Gene-expression values represent mean of log; differential expression test: Wilcoxon rank sum test; avg_logFC= log (mean(group1)/mean(group2)); adjusted p_value: Bonferroni Correction; min.pct ≥10%; avg_logFC ≥ 0.1.

TLR4-expressing ICA cells do not produce TNF-α upon LPS stimulation

In order to further clarify the role of ICA cells in LPS-induced cardiac TNF-α production, we investigated whether ICA cells are responsible for TNF-α production. To this end, we performed co-immunofluorescence staining of TNF-α, TH, and cTn I in LPS-treated NRVM ICA cell+. Surprisingly, TNF-α was induced in cardiomyocytes but not in ICA cells (Fig. 5a). To validate this phenotype, we implored single-cell RNA sequencing to confirm TNF-α expression by cardiomyocytes and ICA cells. The batch-to-batch variations between the control and LPS groups were normalized to be comparable (Fig. 5c). Distinct populations of cardiac cells were identified in different clusters on the t-SNE map (Fig. 5d). Unsupervised clustering revealed macrophages expressing Cd68 and ICA cells expressing Dbh in two separate clusters, supporting our immuno-staining results that ICA cells were not of monocyte origin (Fig. 5d, e). Analysis of substructure in cluster 3 (ICA cells and cardiomyocytes) showed four distinct groups in which the new sub-cluster 3 (purple) was ICA cells expressing Dbh (Fig. 5f, g). Further, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) heat maps and clusters displayed an upregulation of Dbh and Jun expression, but not Tnf expression in LPS-treated ICA cells (Fig. 5h). LPS-stimulated macrophages were used as a positive control, resulting in upregulation of Tnf, Il1b, and Il6 gene expression (Fig. 5i). Mechanistically, analyses of DEGs showed significantly increased expressions of Nfkbia and Tnfaip6 in LPS-treated ICA cells compared with controls (Fig. 5j, k and Fig. S6C, D). These data suggest the lack of TNF-α production in ICA cells may be attributed to the upregulation of Nfkbia and Tnfaip6, which are involved in p65 nuclear translocation30, and suppression of NF-κB activation31, respectively. We, therefore, performed immunofluorescence staining of p65 localization to examine NF-κB activation in LPS-treated NRVM ICA cell+. Strikingly, nuclear translocation of p65 was significantly induced by LPS in non-ICA cells but not in ICA cells, compared to saline-treated controls (Fig. 5l). These findings suggest that ICA cells lack the capacity of producing TNF-α due to impaired nuclear translocation of p65 by elevation of Nfkbia and Tnfaip6.

ICA cell-derived NE acts via β1-AR-CaMKII signaling to regulate NF-κB and MAPK pathways in cardiomyocyte

Catecholamines activate various adrenoceptors, to screen out the targets of ICA cell-derived NE in cardiomyocytes, different adrenoceptor inhibitors were employed, in which only β1-AR or β2-AR blockade significantly reduced the LPS-induced TNF-α production in NRVM ICA cell+ (Fig. 6a). Administration of CGP20712A (2 µM), a β1-AR blocker, prior to LPS (1 μg/mL) treatment dramatically suppressed LPS-induced phosphorylation of IκBa and p65 (Fig. 6b), which is consistent with previous work demonstrating activation of β1-AR increases IκBα phosphorylation and TNF-α expression in septic mouse hearts11. The levels of phosphorylated-p38 and phosphorylated-JNK in the CGP20712A + LPS group were also significantly decreased compared to the LPS alone group, while the ERK1/2 phosphorylation was increased by CGP20712A with or without LPS (Fig. 6c). These results suggest that the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways are involved in the process of ICA cell-derived NE promotion of cardiomyocyte TNF-α production. Since protein kinase A (PKA) signaling has proven to be a major route for channeling cardiac β1-AR signaling32, we thus asked if PKA mediates induction of ICA cell-derived NE on NF-κB and MAPK pathway activation. Intriguingly, the phosphorylation of CREB-Ser133, which indicates PKA activation33, showed no significant alteration in either of the groups (Fig. 6d). As the other major downstream element of the β1-AR pathway, CaMKII was reported to mediate effects of β1-AR stimulation independent of PKA in heart failure, cardiac contractility, and apoptosis34. A recent study also showed that CaMKII plays an important role in cardiac contractile dysfunction associated with sepsis35. We, therefore, examined the activation of CaMKII in this process. Indeed, the phosphorylation of CaMKIIThr286 was dramatically enhanced in LPS-stimulated NRVM ICA cell+ compared with controls, while CGP20712A significantly reduced CaMKIIThr286 phosphorylation compared to the LPS group (Fig. 6e). These data hint that CaMKIIThr286 phosphorylation is critical in mediating the effects of β-AR stimulation by ICA cell-derived NE. We next used KN93, a selective inhibitor of CaMKII, to block CaMKII signaling. KN93 markedly decreased the levels of TNF-α in the supernatants of LPS-treated NRVM ICA cell+ in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6f). The phosphorylation of CaMKIIThr286 in the KN93 + LPS group was significantly reduced compared with LPS-treated NRVM ICA cell+ (Fig. 6g). Accordingly, KN93 dramatically decreased LPS-induced phosphorylation of p65, IkBa, p38, and JNK in NRVM ICA cell+ (Fig. 6h, i), and increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig, 6j). These results show that CaMKII blockade phenocopies the effects of β1-AR blockade on LPS-treated NRVM ICA cell+, which suggests that CaMKII is essential during β1-AR signal transduction activated by ICA cell-derived NE.

a Effect of different adrenoceptor blockers on TNF-α production in NRVM ICA cell+ upon LPS stimulation. Each dot represents a biological replicate. b–e NRVM ICA cell+ were stimulated with 2 µM CGP20712A (β1-AR antagonist) for 30 min prior to 1 µg/mL LPS for 30 min, b phosphorylation of IκBα and p65, c phosphorylation of p38, JNK, and ERK1/2, d phosphorylation of CREB-Ser133, indicating PKA activation. e phosphorylation of CaMKII in NRVM ICA cell+. f TNF-α in supernatants of NRVM ICA cell+ treated with KN93 in different doses for 30 min prior to 1 µg/mL LPS for 6 h. g–j Phosphorylation of CaMKII, p65, IκBα, p38, JNK and ERK1/2 in NRVM ICA cell+ treated with 1 µM KN93 for 30 min prior to 1 µg/mL LPS for 30 min. Data are presented as mean ± SEM using one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparison test, P-values were assigned on each panel. n = 36 neonatal rats (a–j), data represent three or four independent experiments.

Dobutamine recapitulates the contributions of ICA cells to cardiomyocyte TNF-α production upon LPS stimulation

The aforementioned data suggest that the NE from ICA cells contribute to the activation of NF-κB and MAPKs through β1-AR-CaMKII signaling in cardiomyocytes. We next employed dobutamine (DOB), a selective β1-AR agonist analogous to NE36, to recapitulate the contributions of ICA cells. We cultured NRVM without ICA cells (NRVM ICA cell−) and then treated with DOB for different durations prior to LPS stimulation. Short-term (10-min) β1-AR stimulation with DOB reduced the LPS-induced TNF-α production in NRVM ICA cell−, while PKA inhibitor 14–22 amide (PKI) increased LPS-induced TNF-α production and reversed the suppressive effect of DOB (Fig. 7a). Such observations are in agreement with published data suggesting that short-term β1-adrenergic stimulation elicits a rapid increase of cellular cAMP activating PKA37, which inhibits LPS-induced cardiac expression of TNF-α38. Of note, cardiomyocytes are perpetually regulated by intrinsic cardiac adrenergic activities. We thus prolonged the treatment time of DOB, and found that β1-AR stimulation for 6 h significantly increased the level of TNF-α in supernatants of LPS-treated NRVM ICA cell− (Fig. 7b). Similar to our observations regarding ICA cell-derived NE, DOB stimulation of NRVM ICA cell− for 6 h did not alter phosphorylation of CREB-Ser133 (Fig. 7c), but did dramatically enhance the level of phosphorylated-CaMKIIThr286 compared with control and LPS groups (Fig. 7d). The phosphorylation of CaMKIIThr286 in LPS-treated NRVM ICA cell− exhibited negligible differences compared with controls, showing that there was no NE production in NRVM ICA cell− culture due to the lack of ICA cells (Fig. 7d). Consistent with β1-AR blockade and CaMKII blockade in LPS-stimulated NRVM ICA cell+, DOB treatment of NRVM ICA cell− for 6 h prior to LPS markedly increased phosphorylation of IκBα and JNK, whereas a decreased level of phosphorylated-ERK1/2 and comparable p38 phosphorylation when compared with the LPS alone group (Fig. 7e–g). Given that β2-AR activation suppresses p38 MAPK phosphorylation39, the unchanged p38 phosphorylation could be due in part to the mild β2-AR agonist activity of DOB40. Nonetheless, the data collectively shows DOB mimics ICA-cell derived NE that promotes TNF-α production in LPS-stimulated cardiomyocytes via β1-AR-CaMKII-NF-κB/MAPKs signaling cascades.

a TNF-α in supernatants of NRVM without ICA cell (NRVM ICA cell−) treated with 1 µM dobutamine (DOB) for 10 min and/or 5 µM PKA inhibitor 14–22 amide (PKI) for 1 h prior to LPS 1 µg/mL for 6 h. b TNF-α in supernatants of NRVM ICA cell− treated with 1 µM DOB for 3 h or 6 h prior to 1 µg/mL LPS for 12 h. c–g Phosphorylation of CREB-Ser133, CaMKII-Thr286, IκBα, JNK, ERK1/2 and p38 in NRVM ICA cell− treated with 1 µM DOB for 6 h prior to 1 µg/mL LPS for 30 min. n = 36 neonatal rats, data represent three independent experiments (a–g). h, i and k Systolic (+dP/dtmax), diastolic (−dP/dtmin) function and heart rate of Langendorff-perfused adult rat hearts, LPS: 1.5 µg/mL, Nepicastat: Dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH) inhibitor, 15 µg/mL. j TNF-α and NE in myocardial homogenates from adult rat hearts Langendorff perfused for 120 min. n = 7 rats (K-H buffer), n = 7 rats (1.5 µg/mL LPS), n = 5 rats (15 µg/mL Nepicastat + LPS) in (h–k), each dot represents an adult rat, the solid dots on lines in (h) and (i) represent the mean of each group at each time point. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. a–g and j one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparison test, h, i and k two-way repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 in comparison of LPS vs. K-H buffer, ##P < 0.01, #### P < 0.0001 in comparison of LPS vs. Nepicastat + LPS. P-values were assigned on the panels.

Blockade of ICA cell-derived NE prevents LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction

The above mentioned data suggest a critical role of ICA cells in facilitating LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction. We, therefore, attempted to assess the influence of ICA cell-derived NE on cardiac function in vivo. Of note, circulating NE sourced from sympathetic nerves and adrenal medulla are significantly enhanced during sepsis26, however, the impact of ICA cell-derived NE on cardiac function is challenging to measure exclusively in vivo. Yet, the Langendorff perfusion system can eliminate the influence of circulating NE, and has proven invaluable and stalwart in studying pharmacological effects on myocardial function in the investigation of clinically relevant disease states such as heart failure41,42. It was thus utilized to investigate the impact of ICA cells on myocardial dysfunction induced by LPS in adult rats. The hearts in the LPS group exhibited significantly worse phenotypes in both systolic (+dP/dtmax) and diastolic (−dP/dtmin) functions than those in the K-H buffer group (control). Furthermore, blockade of ICA cell-derived NE biosynthesis using Nepicastat, an inhibitor of DBH, markedly rescued both systolic and diastolic functions compared to the LPS group (Fig. 7h, i). Nepicastat simultaneously abrogated the elevation of NE and TNF-α production in LPS-perfused hearts, consistent with changes in systolic and diastolic functions (Fig. 7j). The Langendorff-perfused hearts in different groups showed a negligible alteration in heart rate (Fig. 7k). These findings demonstrate that blockade of ICA cell-derived NE reduces LPS-induced cardiac TNF-α production and protects against LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction.

Discussion

Catecholamines are irreplaceable in both developing and adult hearts. Targeted disruption in mice of the genes encoding catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes are embryonic lethal, likely due to cardiac failure43,44. The developing heart initially relies on ICA cells as the major source of catecholamines45. Published evidence also shows that ICA cells synthesize cardiac intrinsic catecholamines, occurring independently of cardiac sympathetic nerves, either in neonatal or adult hearts, thereby functioning as a critical and integral regulator in mammalian heart development, cardiac pathophysiology and post-heart transplantation support14,15,16,17,19,21,46,47. Stimulation of ICA cells enhances epinephrine release to reduce ischemia/reperfusion injury through the δ-opioid-regulated cardioprotective adrenopeptidergic co-signaling pathway17,19,48. Although ICA cell density shows negligible connection with reduced myocardial efficiency in failing myocardium18, irregular stimulation of ICA cells raises cardiac NE levels49. Considering the increase of cardiac NE levels and β1-AR activation aggravate sepsis-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and myocardial injury8,11, it is thus plausible that ICA cells could promote septic cardiomyopathy pathogenesis. Indeed, ICA cells are not separated from cardiomyocytes in most of the current cardiac models using primary neonatal rat or mouse ventricular myocytes (NRVM or NMVM)50,51. Our previous study established a method of superparamagnetic iron oxide particle (SIOP) to purify NRVM from ICA cells and demonstrated that the ICA cell-free NRVM showed lower calcium transient amplitude, longer time to begin autonomous beating and less expression of natriuretic peptide A (Nppa) and -B (Nppb) (markers of stress response) than those of NRVM mixed with ICA cells24. Moreover, we observed a reduced TNF-α production in ICA cell-free NRVM compared to unpurified cardiomyocytes in response to LPS stimulation24. Therefore, it is important to distinguish and evaluate the function of ICA cells in cardiac studies.

In the current study, we defined ICA cell-derived NE as a contributor to myocardial dysfunction via activation of β1-AR signaling in cardiomyocytes upon LPS challenge. Our data demonstrated ICA cells as a source of increased NE in LPS-treated neonatal and adult rat hearts. Although endothelial cells have been shown to produce catecholamines in response to ischemia52, the typical “cobblestone” monolayer pattern of morphology in endothelial cell culture largely differs from ICA cells53. In the Langendorff perfusion experiments, the unchanged NE levels in the perfusate from LPS-perfused hearts also indicate that the increased NE levels in the hearts were not from vascular endothelial cells. Utilization of a β1-AR blocker, CaMKII inhibitor, and β1-AR agonist showed that the NE from ICA cells can active cardiac β1-AR-CaMKII signaling, which crosstalks with NF-κB and MAPK pathways to promote TNF-α production and myocardial dysfunction during sepsis. This concept was further evidenced by the administration of Nepicastat inhibiting NE production in the ex vivo Langendorff model assessing septic heart function.

The early phase of sepsis has been characterized by high levels of circulating catecholamines, which boost the inflammatory response26, but the molecular mechanisms are multifactorial and not yet fully understood. TLR4, mediating recognition of LPS, has been well-known as the first-line sentinel of host defense against bacteria in innate immunity26. Previous studies show that TLR4 is present on immune cells and neurons4,54 which possess the capacity of catecholamine biosynthesis25,55. Whether TLR4 has functions in the regulation of catecholamine secretion remains elusive. We observed that TLR4 and its downstream MyD88/TRIF-AP-1 signaling pathway mediate LPS-induced biosynthesis of cellular NE through upregulation of NE-producing enzyme expression, assessed by the activation of TH-promoter. Consistently, a previous study showed that LPS continuously increased TH expression in mouse brains56, suggesting a promotive action to catecholamine biosynthesis for TLR4. Intriguingly, although the activation of TLR4 triggers cytokine release including TNF-α26, this is not the case in ICA cells despite TLR4 presence. This discrepancy could be due to the upregulation of Nfkbia and Tnfaip6 expression that results in impaired p65 nuclear translocation in LPS-treated ICA cells. This concept fits well with published evidence that the increase of either Nfkbia or Tnfaip6 expression suppresses NF-κB activation30,31. These findings hint towards a function of TLR4 signaling in hormone regulation during sepsis. In addition, the marked upregulations of chemokine family gene expression (i.e., Cxc3cl1, ccl3, cxcl1, ccl2, etc.) in LPS-treated ICA cells indicate that ICA cells may also contribute to cell migration involved in homeostatic and inflammatory processes.

PKA and CaMKII are two major downstream elements of β1-AR that is critical for the regulation of cardiac function in chronic heart failure37,57. In this study, we demonstrated an essential role for CaMKII in the pathogenesis of LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction. CaMKII activation was not observed in LPS-treated NRVM without the presence ICA cells in culture, whereas PKA activation showed no change. Recent evidence shows that CaMKII oxidation in response to myocardial infarction contributes to NF-κB-dependent inflammatory transcription in cardiomyocytes58. Moreover, it is also reported that oxidation-activated CaMKII has a causal role in the contractile dysfunction during sepsis35. Therefore, the present study demonstrates that ICA cell-derived NE is another factor in activating cardiomyocyte CaMKII via β1-AR to enhance LPS-induced cardiac inflammation, and β1-AR-CaMKII activation is the principal mechanism by which ICA cell-derived NE enhances cardiomyocyte NF-κB and MAPK signaling to promote LPS-induced cardiomyocyte TNF-α production.

In summary, we provide evidence for a pro-inflammatory role of ICA cells in LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction. Our data reveal that TLR4-MyD88/TRIF-AP-1 signaling is responsible for LPS-induced biosynthesis of NE that serves as a paracrine signal to aggravate LPS-induced myocardial TNF-α production and dysfunction via β1-AR-CaMKII signaling (Fig. 8). Considering the observation that blockade of ICA cell-derived NE prevents LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction in adult rat hearts, it seems plausible that ICA cells and CaMKII may be potential therapeutic targets in the fight against SIMD.

ICA cell produces no TNF-α due to the elevated Nfkbia and Tnfaip6 expression. Increased NE release by LPS-TLR4 signaling activates β1-AR-CaMKII signaling in cardiomyocytes to regulate NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, subsequently aggravating myocardial TNF-α production and dysfunction.

Methods

Animals and cell line

The experiments with animals were conducted in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health59 and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Jinan University. Neonatal (1–3 days) and adult (8–10 weeks) Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from the laboratory animal center of Southern Medical University (Guangzhou, China). TLR4-deficient mice (Tlr4Lps-del, strain: C57BL/10ScNJNju) were purchased from Nanjing Biomedical Research Institute of Nanjing University. For neonatal rats and mice, both male and female were used. For adult rats, male were used due to the impact of sex on septic cardiomyopathy60 and the differences in TNF-α levels and vascular reactivity of female following the administration of endotoxin61. HEK293/hTLR4-HA cells (InvivoGen) was a gift from Guang Yang (Jinan University).

Inhibitors

α1-AR antagonist: Prazosin (Sigma-Aldrich#7791); α2-AR antagonist: Yohimbine (Sigma-Aldrich #Y3125); α2A-AR antagonist: BRL 44408 (Sigma-Aldrich #B4559); β1-AR antagonist: CGP20712A (Sigma-Aldrich #C231); β2-AR antagonist: ICI-118 551 (Sigma-Aldrich #I127); β3-AR antagonist: SR59230A (Sigma-Aldrich #S8688); TLR4 inhibitor: Viper peptide (Novus#NBP2-226244); CaMKII inhibitor: KN-93 Phosphate (Selleckchem #S7423); DBH inhibitor: Nepicastat (MCE MedChem Express#HY-13289); PKA Inhibitor: 14-22 Amide (Calbiochem® #476485).

Isolation of primary NRVM and ICA cells

Co-culture of NRVM and ICA cells (NRVM ICA cell+), NRVM without ICA cell (NRVM ICA cell−) and ICA cells were isolated and purified using the published methods24. Briefly, the neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats (1–3 days) were deeply anesthetized by inhalation of CO2, and then the hearts were excised and transferred to pre-cold PBS. (1) NRVM ICA cell+ isolation: the heart tissues were digested 5–6 times using 0.125% trypsin without EDTA (pH 7.30–7.40) to harvest NRVM ICA cell+, and cultured in complete DMEM (10% FBS, 0.1 mM HEPES and 100U/ml Penicillin-Streptomycin) for downstream use (Fig. S1A). (2) NRVM ICA cell− purification using superparamagnetic iron oxide particles (SIOP) (BioMag#BM547): NRVM ICA cell+ suspensions were centrifuged at 800 rpm, 4 °C for 7 min. The pellets were suspended in the pre-cold SIOP solution (40uL SIOP: 4 ml PBS), and then applied magnet (Life technologies™) to the side of the tube for 5-10 min to isolate NRVM ICA cell−, which contained no ICA cells. The supernatant containing NRVM were centrifuged and the NRVM pellets were suspended in complete DMEM for culture. (3) ICA cell isolation: the SIOP binding ICA cells obtained from the last step were washed with ice-cold PBS, centrifuged, and suspended in complete DMEM for further use.

Langendorff perfusion

Myocardial functions of the adult rats were measured using a Langendorff perfusion system as we described previously62. Briefly, the Sprague-Dawley rats (8–10 weeks) were heparinized (i.p. injection heparin, 2000 U) for 15 min, and then deeply anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation (3% isoflurane in 100% oxygen at a flow rate of 1 L/min) using a face mask. The hearts were isolated and the aortas were retrograde set up to a Langendorff perfusion apparatus (Radnoti Langendorff system#120102EZ) with a recirculating mode (volume of 50 mL) to perfuse at 10 mL/min with Krebs-Henseleit buffer (bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 gas mixture and maintained at 37 °C). Rat hearts were divided into groups of K-H buffer (control) or LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, #L2880, Escherichia coli, 055: B5, 1.5 µg/mL). The hearts were then perfused for 140 min with K-H buffer or LPS (1.5 µg/mL) using the recirculating mode, respectively. Perfusion fluid was collected at different time points, and heart tissues were harvested at the end of perfusion. In separate experiments, adult rat hearts were arranged into groups of K-H buffer (control), LPS or LPS + Nepicastat. After a 30-min equilibration perfusion in K-H buffer, a mixture of LPS (1.5 µg/mL) or/and Nepicastat (a selective DBH inhibitor63, 15 µg/mL) were perfused for 2 h. The physiological parameters of hearts were continuously recorded. The perfusate and left ventricular tissues were harvested for TNF-α and NE concentration determination as well as immunofluorescence staining (Fig. S1F).

10X genomics single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis

The strategy for single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of cardiac cells is shown in Fig. 5b. The neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats (1–3 days) were deeply anesthetized with CO2 and the hearts were excised and washed in cold PBS to remove the blood. Heart tissues were minced into ~1 mm3 masses and digested using 0.125% trypsin. (1) Cells were prepared using a modified Percoll gradient procedure described previously to enrich ICA cells64, of which details are described in Supplementary material. Immuno-staining of the cells was performed to examine the existence of ICA cells prior to single-cell RNA sequencing (Fig. S6A). (2) 10X genomics single-cell RNA sequencing: the cells were collected after treatment and analyzed to determine the viability of more than 90% by a cell count system. Individual samples were then loaded on the 10X Genomics Chromium System. Cells counted in the system were around 1.1–1.2 × 104 per group (Fig. S6B). The libraries were prepared following 10X Genomics protocols and sequenced under standard procedure, followed by cell lysis and barcoded reverse transcription of RNA. The library construction and sequencing as well as computational analysis of data were performed at the Guangzhou Saliai Stem cell science and technology company. Single-cell gene expression was visualized in a two-dimensional projection with t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) map, in which all cells were grouped into 10 clusters (distinguished by their colors), and non-linear dimensional reduction was used (Fig. 5d)65. Analyses of batch effect correction and Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were performed using the Seurat (version: 2.3.4) function, RunCCA and FindClusters; Resolution for granularity: 0.5; Differential expression test: Wilcoxon rank sum test; avg_logFC = log(mean(group1)/mean(group2)); adjusted p_value: Bonferroni Correction; min.pct ≥10%; avg_logFC ≥ 0.1.

Immunofluorescence staining

The immunofluorescence staining (IF) was performed according to our previous publication with minor modification22. Briefly, cells or tissue slices were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min followed by two washes with cold PBS and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 min. The specimens were then blocked at room temperature (RT) for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. On the second day, the specimens were washed three times with cold PBS and then incubated in the dark with secondary antibodies at RT for 1 h, and then washed twice with cold PBS, followed by counterstaining with DAPI solution in the dark at RT for 10 min. The specimens were observed using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP8 X). Details of buffer preparation and antibody dilution are listed in Table S2.

ELISA, Western blotting, and Quantitative RT-PCR assay

NE and TNF-α concentration in heart tissues, perfusate, and cell supernatants were determined using the NE research enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (ALPCO#17-NORHU-E01-RES) and the TNF-α Quantikine ELISA kit (R&D System#RTA00), respectively. The western blotting assays of proteins were performed using standard protocol22. Antibodies for western blotting assays are available in the Supplementary Methods. Quantitative RT-PCR assay of relative mRNA expression was analyzed using standard real-time PCR protocol according to TAKARA qPCR kits. In brief, total RNA was reverse transcribed using a PrimeScriptTM RT Reagent Kit (TAKARA#RR047A). Real-time PCR were performed with the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TAKARA#RR820A) in a LightCycler480 real-time PCR system. Primer sequences for genes are shown in Table S3.

Plasmids, molecular cloning, and reporter analysis

The pGL3-Basic Luciferase Reporter vector (Promega), pcDNA3.1 plasmid, plasmids encoding human TRIF and MyD88, RLTK-Luci, and AP-1-Luci reporters were a gift from Fuping You (Peking University)66,67. For reporter assays, a recombinant pGL3-Rat-TH-Luci reporter was designed and cloned (Fig. S4B–D), and then verified by sequencing the relevant region (Supplementary Data 2, Fig. S4E, F). The EGFP plasmid was used as transfection efficiency control (Fig. S4G). HEK293/hTLR4-HA cells seeded in 24-well plates were transfected with 50 ng of the luciferase reporter together with a total of 300 ng various expression plasmids or control plasmids. Quantification of dual-luciferase activity was performed using a GALEN dual-luciferase assay kit (GALEN#GN201).

RNA interference

RNA interference was designed to disrupt AP-1 binding in the rat TH promoter region (Fig. S5A–C). c-Jun siRNA, c-Fos siRNA (Sequences refer to Table S4), and control siRNA transfection were processed using Lipofectamine®3000 Reagent (Invitrogen™#L3000001) and Opti-MEM (Gibco#31985-070) under a standard protocol.

Isolation of rat peritoneal macrophages

Rat peritoneal macrophages were isolated using a published method68. Adult rats (250–300 g) were euthanized with CO2 plus cervical dislocation, and then the abdomen was soaked with 70% alcohol followed by making a small incision along the midline. 10 ml of DMEM were injected into each rat peritoneal cavity and gently massaged. About ~8 ml of fluid was aspirated from the peritoneum per rat. The peritoneal cells were collected by centrifuging for 10 min, 400 × g at 4 °C, and cultured for downstream use.

Statistics and reproducibility

All data were analyzed for statistical significance with SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Two-tailed independent Student’s t-test was used for two groups comparison. More than two groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison test for normally distributed and equal variance data, or nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s method of comparison for non-normal distributions. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, where n is the number of animals. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Statistical details, including sample sizes and experiment repeats, are reported in the figures and figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are included in the paper and Supplementary files, and available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The single-cell RNA-seq data have been deposited in GEO (GSE189964). The uncropped gel and images for western blots are provided in the Supplementary Information. The source data behind all graphs and charts in the main manuscript are included in the Supplementary Data 1 file. The sequence of the recombinant pGL3-Rat-TH-Luci reporter plasmid is in the Supplementary Data 2 file.

References

Aneman, A. & Vieillard-Baron, A. Cardiac dysfunction in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 42, 2073–2076 (2016).

Hollenberg, S. M. & Singer, M. Pathophysiology of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18, 424–434 (2021).

Avlas, O., Fallach, R., Shainberg, A., Porat, E. & Hochhauser, E. Toll-like receptor 4 stimulation initiates an inflammatory response that decreases cardiomyocyte contractility. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 1895–1909 (2011).

van der Poll, T., van de Veerdonk, F. L., Scicluna, B. P. & Netea, M. G. The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 407–420 (2017).

Lv, X. & Wang, H. Pathophysiology of sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction. Military Med. Res. 3, 30 (2016).

Han, C. et al. Acute inflammation stimulates a regenerative response in the neonatal mouse heart. Cell Res. 25, 1137–1151 (2015).

Honda, T., He, Q., Wang, F. & Redington, A. N. Acute and chronic remote ischemic conditioning attenuate septic cardiomyopathy, improve cardiac output, protect systemic organs, and improve mortality in a lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis model. Basic Res. Cardiol. 114, 15 (2019).

Rudiger, A. & Singer, M. Mechanisms of sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction. Crit. Care Med. 35, 1599–1608 (2007).

Andreis, D. T. & Singer, M. Catecholamines for inflammatory shock: a Jekyll-and-Hyde conundrum. Intensive Care Med. 42, 1387–1397 (2016).

Staedtke, V. et al. Disruption of a self-amplifying catecholamine loop reduces cytokine release syndrome. Nature 564, 273–277 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Beta(1)-adrenoceptor stimulation promotes LPS-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through activating PKA and enhancing CaMKII and IkappaBalpha phosphorylation. Crit. Care 19, 76 (2015).

Morelli, A. et al. Effect of heart rate control with esmolol on hemodynamic and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock: a randomized clinical trial. Jama 310, 1683–1691 (2013).

Kimmoun, A. et al. beta1-Adrenergic inhibition improves cardiac and vascular function in experimental septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 43, e332–e340 (2015).

Huang, M. H. et al. An intrinsic adrenergic system in mammalian heart. J. Clin. Investig. 98, 1298–1303 (1996).

Ebert, S. N. & Thompson, R. P. Embryonic epinephrine synthesis in the rat heart before innervation: association with pacemaking and conduction tissue development. Circ. Res. 88, 117–124 (2001).

Tamura, Y. et al. Neural crest-derived resident cardiac cells contribute to the restoration of adrenergic function of transplanted heart in rodent. Cardiovasc. Res. 109, 350–357 (2016).

Huang, M. H. et al. Reducing ischaemia/reperfusion injury through delta-opioid-regulated intrinsic cardiac adrenergic cells: adrenopeptidergic co-signalling. Cardiovasc. Res. 84, 452–460 (2009).

van Eif, V. W., Bogaards, S. J. & van der Laarse, W. J. Intrinsic cardiac adrenergic (ICA) cell density and MAO-A activity in failing rat hearts. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motility 35, 47–53 (2014).

Huang, M. H. et al. Mediating delta-opioid-initiated heart protection via the beta2-adrenergic receptor: role of the intrinsic cardiac adrenergic cell. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. 293, H376–H384 (2007).

Mahmoud, A. I. & Lee, R. T. Adrenergic function restoration in the transplanted heart: a role for neural crest-derived cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 109, 348–349 (2016).

Huang, M. H. et al. Neuroendocrine properties of intrinsic cardiac adrenergic cells in fetal rat heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. 288, H497–H503 (2005).

Yu, X. et al. adrenoceptor activation by norepinephrine inhibits LPS-induced cardiomyocyte TNF-α production via modulating ERK1/2 and NF-κB pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 18, 263–273 (2014).

Natarajan, A. R., Rong, Q., Katchman, A. N. & Ebert, S. N. Intrinsic cardiac catecholamines help maintain beating activity in neonatal rat cardiomyocyte cultures. Pediatr. Res. 56, 411–417 (2004).

Yang, D. et al. A new method for neonatal rat ventricular myocyte purification using superparamagnetic iron oxide particles. Int. J. Cardiol. 270, 293–301 (2018).

Flierl, M. A. et al. Phagocyte-derived catecholamines enhance acute inflammatory injury. Nature 449, 721–725 (2007).

Rittirsch, D., Flierl, M. A. & Ward, P. A. Harmful molecular mechanisms in sepsis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 776–787 (2008).

Frantz, S. et al. Toll4 (TLR4) expression in cardiac myocytes in normal and failing myocardium. J. Clin. Investig. 104, 271–280 (1999).

Lysakova-Devine, T. et al. Viral inhibitory peptide of TLR4, a peptide derived from vaccinia protein A46, specifically inhibits TLR4 by directly targeting MyD88 adaptor-like and TRIF-related adaptor molecule. J. Immunol. 185, 4261–4271 (2010).

Nagamoto-Combs, K., Piech, K. M., Best, J. A., Sun, B. & Tank, A. W. Tyrosine hydroxylase gene promoter activity is regulated by both cyclic AMP-responsive element and AP1 sites following calcium influx. Evidence for cyclic amp-responsive element binding protein-independent regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 6051–6058 (1997).

Anest, V. et al. A nucleosomal function for IkappaB kinase-alpha in NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression. Nature 423, 659–663 (2003).

Mittal, M. et al. TNFα-stimulated gene-6 (TSG6) activates macrophage phenotype transition to prevent inflammatory lung injury. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E8151–E8158 (2016).

Whelan, R. S., Konstantinidis, K., Xiao, R. P. & Kitsis, R. N. Cardiomyocyte life-death decisions in response to chronic beta-adrenergic signaling. Circ. Res. 112, 408–410 (2013).

Gonzalez, G. A. & Montminy, M. R. Cyclic AMP stimulates somatostatin gene transcription by phosphorylation of CREB at serine 133. Cell 59, 675–680 (1989).

Grimm, M. & Brown, J. H. β-Adrenergic receptor signaling in the heart: role of CaMKII. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48, 322–330 (2010).

Sepúlveda, M. et al. Calcium/calmodulin protein kinase II-dependent ryanodine receptor phosphorylation mediates cardiac contractile dysfunction associated with sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 45, e399–e408 (2017).

Stapel, B. et al. Low STAT3 expression sensitizes to toxic effects of beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 38, 349–361 (2017).

Wang, W. et al. Sustained beta1-adrenergic stimulation modulates cardiac contractility by Ca2+/calmodulin kinase signaling pathway. Circ. Res. 95, 798–806 (2004).

Wagner, D. R. et al. Adenosine inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Circ. Res. 82, 47–56 (1998).

Zhang, F. F. et al. Stimulation of spinal dorsal horn beta2-adrenergic receptor ameliorates neuropathic mechanical hypersensitivity through a reduction of phosphorylation of microglial p38 MAP kinase and astrocytic c-jun N-terminal kinase. Neurochem. Int. 101, 144–155 (2016).

Tibayan, F. A., Chesnutt, A. N., Folkesson, H. G., Eandi, J. & Matthay, M. A. Dobutamine increases alveolar liquid clearance in ventilated rats by beta-2 receptor stimulation. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 156, 438–444 (1997).

Liao, R., Podesser, B. K. & Lim, C. C. The continuing evolution of the Langendorff and ejecting murine heart: new advances in cardiac phenotyping. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. 303, H156–H167 (2012).

Bell, R. M., Mocanu, M. M. & Yellon, D. M. Retrograde heart perfusion: the Langendorff technique of isolated heart perfusion. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 50, 940–950 (2011).

Zhou, Q. Y., Quaife, C. J. & Palmiter, R. D. Targeted disruption of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene reveals that catecholamines are required for mouse fetal development. Nature 374, 640–643 (1995).

Thomas, S. A., Matsumoto, A. M. & Palmiter, R. D. Noradrenaline is essential for mouse fetal development. Nature 374, 643–646 (1995).

Fedele, L. & Brand, T. The intrinsic cardiac nervous system and its role in cardiac pacemaking and conduction. J Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 7, 54 (2020).

Ebert, S. N. & Taylor, D. G. Catecholamines and development of cardiac pacemaking: an intrinsically intimate relationship. Cardiovasc. Res. 72, 364–374 (2006).

Nguyen, V. T. et al. Delta-opioid augments cardiac contraction through beta-adrenergic and CGRP-receptor co-signaling. Peptides 33, 77–82 (2012).

Huang, M. H., Poh, K. K., Tan, H. C., Welt, F. G. & Lui, C. Y. Therapeutic synergy and complementarity for ischemia/reperfusion injury: beta1-adrenergic blockade and phosphodiesterase-3 inhibition. Int. J. Cardiol. 214, 374–380 (2016).

Saygili, E. et al. Irregular electrical activation of intrinsic cardiac adrenergic cells increases catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 413, 432–435 (2011).

Sreejit, P., Kumar, S. & Verma, R. S. An improved protocol for primary culture of cardiomyocyte from neonatal mice. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. - Animal 44, 45–50 (2008).

Zhao, J. et al. The different response of cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts to mitochondria inhibition and the underlying role of STAT3. Basic Res. Cardiol. 114, 12 (2019).

Sorriento, D. et al. Endothelial cells are able to synthesize and release catecholamines both in vitro and in vivo. Hypertension 60, 129–136 (2012).

Jiménez, N., Krouwer, V. J. D. & Post, J. A. A new, rapid and reproducible method to obtain high quality endothelium in vitro. Cytotechnology 65, 1–14 (2013).

Zhao, M., Zhou, A., Xu, L. & Zhang, X. The role of TLR4-mediated PTEN/PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway in neuroinflammation in hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience 269, 93–101 (2014).

Huang, H. P. et al. Physiology of quantal norepinephrine release from somatodendritic sites of neurons in locus coeruleus. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 5, 29 (2012).

Girard-Joyal, O. & Ismail, N. Effect of LPS treatment on tyrosine hydroxylase expression and Parkinson-like behaviors. Hormones Behavior 89, 1–12 (2017).

Zhu, W. Z. et al. Linkage of beta1-adrenergic stimulation to apoptotic heart cell death through protein kinase A-independent activation of Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II. J. Clin. Investig. 111, 617–625 (2003).

Singh, M. V. et al. MyD88 mediated inflammatory signaling leads to CaMKII oxidation, cardiac hypertrophy and death after myocardial infarction. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 52, 1135–1144 (2012).

National Research Council Committee for the Update of the Guide for the, C. & Use of Laboratory, A. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. in Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academies Press (US) Copyright © 2011, National Academy of Sciences., Washington (DC), 2011).

Choudhry, M. A., Bland, K. I. & Chaudry, I. H. Gender and susceptibility to sepsis following trauma. Endocrine, Metabolic Immune Disorders Drug Targets 6, 127–135 (2006).

van Eijk, L. T. et al. Gender differences in the innate immune response and vascular reactivity following the administration of endotoxin to human volunteers. Crit. Care Med. 35, 1464–1469 (2007).

Yu, X. et al. alpha2A-adrenergic blockade attenuates septic cardiomyopathy by increasing cardiac norepinephrine concentration and inhibiting cardiac endothelial activation. Sci. Rep. 8, 5478 (2018).

Stanley, W. C. et al. Catecholamine modulatory effects of nepicastat (RS-25560-197), a novel, potent and selective inhibitor of dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Br. J. Pharmacol. 121, 1803–1809 (1997).

Golden, H. B. et al. Isolation of cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts from neonatal rat pups. Methods Mol. Biol. 843, 205–214 (2012).

Dimitriadis, G., Neto, J. P. & Kampff, A. R. t-SNE visualization of large-scale neural recordings. Neural Comput. 30, 1750–1774 (2018).

You, F. et al. ELF4 is critical for induction of type I interferon and the host antiviral response. Nat. Immunol. 14, 1237–1246 (2013).

Hu, Y., O’Boyle, K., Auer, J. & Raju, S. Multiple UBXN family members inhibit retrovirus and lentivirus production and canonical NFκΒ signaling by stabilizing IκBα. PLoS Pathogens 13, e1006187 (2017).

Zhang, X., Goncalves, R. & Mosser, D. M. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages. Curr. Protocols Immunol. Chapter 14, Unit 14.11 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank Fuping You in Peking University Health Science Center for the plasmids. We thank Bo Yu and Quan Yu in the Medical Experimental Center of School of Medicine at Jinan University for expert technical assistance in using confocal microscopy. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81871542).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Y. and H.W. conceived the study and designed the experiments. D.Y. performed the majority of the experiments and analyzed the data; X.D., Y.X., X.T., G.Y., H.L., X.L., and X.Y. contributed specific experiments and data analysis. D.Y. and H.W. wrote the paper. P.W., A.H., and J.C. assisted in editing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Christoph Thiemermann and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jesmond Dalli and Eve Rogers.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, D., Dai, X., Xing, Y. et al. Intrinsic cardiac adrenergic cells contribute to LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction. Commun Biol 5, 96 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03007-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03007-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.