Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to cardiac pathologies. Barriers to new therapies include an incomplete understanding of underlying molecular culprits and a lack of effective mitochondria-targeted medicines. Here, we test the hypothesis that the cardiolipin-binding peptide elamipretide, a clinical-stage compound under investigation for diseases of mitochondrial dysfunction, mitigates impairments in mitochondrial structure-function observed after rat cardiac ischemia-reperfusion. Respirometry with permeabilized ventricular fibers indicates that ischemia-reperfusion induced decrements in the activity of complexes I, II, and IV are alleviated with elamipretide. Serial block face scanning electron microscopy used to create 3D reconstructions of cristae ultrastructure reveals that disease-induced fragmentation of cristae networks are improved with elamipretide. Mass spectrometry shows elamipretide did not protect against the reduction of cardiolipin concentration after ischemia-reperfusion. Finally, elamipretide improves biophysical properties of biomimetic membranes by aggregating cardiolipin. The data suggest mitochondrial structure-function are interdependent and demonstrate elamipretide targets mitochondrial membranes to sustain cristae networks and improve bioenergetic function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The biophysical organization of the mitochondrial inner membrane regulates bioenergetics. Studies spanning fifty years have described the intertwined relationship between mitochondrial structure and function1,2, bolstered in more recent years by advances in imaging modalities3,4,5. The composition of the inner membrane is unique, comprised predominantly of phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, and cardiolipin (CL). Notably, CL represents a structurally distinct anionic phospholipid enriched in the mitochondrial inner membrane6,7. CL is postulated to exist in microdomains (i.e., distinct membrane regions enriched in CL) that influence mitochondrial structure-function8. CL is found at negatively curved regions of the inner membrane, including cristae contact sites and along the inner leaflet of cristae tubules6. CL is essential for protein import, localization, and assembly, profoundly influencing mitochondrial dynamics, energetics, and network continuity9,10. Previous studies established oxidation and subsequent lowering of CL content across cardiac pathologies, including acute ischemia-reperfusion (I/R)11,12 and heart failure13,14,15. Aside from exogenous perfusion with CL16, which may only be applicable in experimental settings, there are currently no therapies that can improve mitochondrial function by targeting CL.

A number of cell permeable, mitochondria-targeting peptides have emerged over the last two decades. This class of peptides typically contain residues of alternating cationic-aromatic motifs ranging from 4–16 amino acids (reviewed in ref. 17). Elamipretide (formerly known as MTP-131, Bendavia, SS-31) is a cell-permeable peptide currently being investigated in several clinical trials to mitigate mitochondrial dysfunction associated with genetic- and age-related mitochondrial diseases. This peptide consists of a tetrapeptide sequence of D-arginine-dimethyltyrosine-lysine-phenylalanine. Preclinical studies spanning numerous models and laboratories have demonstrated preserved mitochondrial function and cytoprotection with this peptide (reviewed in refs. 18,19,20), although the mechanism of action has remained elusive. Previous work demonstrated that elamipretide interacted with CL21, yet the physiological consequences of this interaction are not fully understood. In this study, we utilized high-resolution mitochondrial respiration and simultaneous reactive oxygen species emission assays, biophysical membrane models, and mitochondrial imaging (serial block-face scanning- and transmission electron microscopy), to test the hypothesis that elamipretide would improve post-ischemic mitochondrial structure-function by aggregating mitochondrial CL molecules.

Results

Effects of I/R and elamipretide on mitochondrial respiration

We first confirmed previous studies of myocardial uptake and mitochondrial localization using a TAMRA-conjugated elamipretide (Supplemental Fig. 1). Mitochondrial functional studies are presented in Fig. 1. In permeabilized ventricular fibers isolated after reperfusion (“Post-I/R” Fibers), respiratory control ratios (RCR; using glutamate/malate substrate) fell from 3.6 ± 0.2 in normoxic fibers to 1.9 ± 0.1 after I/R. This decrement was partially blunted with peptide treatment, with elamipretide leading to a post-I/R RCR of 2.5 ± 0.1. The substrate-uncoupler-inhibitor-titration (SUIT) protocol employed indicated decrements (average of −78% during state 3) in mitochondrial respiration across complexes I–IV after ischemia-reperfusion. Post-ischemic administration of elamipretide improved mitochondrial respiration with complex I and II substrate by an average of 56% during state 3 conditions (P < 0.05 compared to ischemia-reperfusion alone, Fig. 1a), and tended to improve complex IV-dependent respiration (+21%). Improved mitochondrial bioenergetics was also supported by higher myocardial oxygen consumption in the intact heart in post-ischemic hearts receiving elamipretide.

a Decrements in mitochondrial respiration were seen across different mitochondrial complexes and substrate conditions in permeabilized fibers (N = 7–8 for all groups) and intact hearts (N = 3–4 for all groups), with elamipretide providing improved function across complexes. b In permeabilized ventricular fibers, elamipretide reduced H2O2 emission associated with reoxygenation (N = 74 for all groups). c–e Effects of elamipretide on reverse electron transport (RET) stimulated by succinate administration. Effects of elamipretide RET stimulated by succinate administration. c Representative trace of succinate-supported RET (N = 11–12 per group). d Elamipretide led to modest reductions in RET whether analyzed as an integrated response after succinate or steady-state (N = 11–12 per group). e Rotenone substantially reduced H2O2 emission, with no differences between saline and elamipretide groups (N = 12 for all groups). *P < 0.05 versus normoxic; #P < 0.05 versus saline.

Effects of I/R and elamipretide on H2O2 emission

A major limitation to using fibers in the above paradigm (isolating fibers from the heart after I/R) was the inability to determine whether the observed protection of mitochondrial energetics was a cause or consequence of cardioprotection. Accordingly, we devised a series of studies to determine the efficacy of elamipretide in models where energetics can be measured during the insult. Permeabilized ventricular fibers (from normoxic hearts) were placed in a high-resolution respirometry chamber and respired (saturating ADP present, “State 3”) until they consumed all of the oxygen in the chamber, thus inducing anoxia. To account for variability, each fiber preparation was normalized to its own preanoxia, normoxic value. There were observable increased levels of H2O2 at the onset of reoxygenation. Elamipretide treatment reduced fiber H2O2 emission by 33% (Fig. 1b). This effect persisted whether H2O2 rates were expressed alone or when normalized to the fiber’s simultaneous oxygen consumption rate (−36%).

We then determined if the mechanism of elamipretide involved reduction in reactive oxygen species (ROS) emission through reverse electron transfer (RET), presented in Fig. 1c–e. There was a modest but statistically significant reduction in succinate-derived RET when mitochondria were treated acutely with elamipretide. This was reflected whether the H2O2 emission was integrated over a five-minute timespan after succinate addition (−13%) (Fig. 1d) or normalized to simultaneous oxygen flux (−18%) (Fig. 1d). As expected, treatment with rotenone abolished almost all RET (rates declined from around 40 pmol/sec*mg to around 5 pmol/sec*mg). After rotenone treatment there were no differences in the rates of H2O2 production between the saline and elamipretide-treated mitochondria (Fig. 1e). We could rule out if a subtle but statistically significant decrease in H2O2 emission after rotenone would become apparent with higher N’s. Furthermore, the addition of the complex III blocker antimycin-A was not done in these studies.

These mitochondrial function studies were accompanied by studies to determine the macromolecular/supercomplex assembly of electron transport system proteins. (Supplemental Fig. 2). There was a 27% decrease in the supercomplex coupling (flux control factor) after I/R, which was improved by 10% with elamipretide (Supplemental Fig. 2D), although this did not directly correlate with changes in mitochondrial supercomplex band density (Supplemental Fig. 2A, C). There was a decrease in native complex V after I/R (−51%), which was abrogated with elamipretide (+47% versus I/R control) (Supplemental Fig. 2B, E). Although previous studies have extracted supercomplex bands from the gel and measured discernible respiration22, in our hands the changes in respiration when substrates were given appeared to be an artifact, as it was observed even when nonloaded acrylamide gel was placed into the respirometer.

Effects of I/R and elamipretide on mitochondrial structure

Given the integral relationships between mitochondrial function and structure4,23, we employed two different electron microscopy imaging modalities to determine mitochondrial morphology. Results from transmission electron microscopy are presented in Fig. 2, with representative images in Fig. 2a and Supplemental Fig. 3. Ischemia-reperfusion induced an 18% increase in mitochondrial swelling, with I/R-saline-treated hearts displaying a greater Feret diameter when compared to normoxic hearts (Fig. 2b, P < 0.05 versus control). Treatment with elamipretide did not markedly influence mitochondrial swelling based on transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging. I/R induced a 35% decrease in mitochondrial electron density (P < 0.05, Fig. 2c), which was attenuated with elamipretide treatment by 34%. Sarcomeric contracture (z-band width) was prominent with ischemia-reperfusion (1.48 μM Normoxia vs. 1.18μM I/R + Saline, P < 0.05), and was not affected by post-ischemic elamipretide treatment (1.18 μM I/R + Saline vs. 1.14 μM I/R + Elamipretide). These sarcomere lengths were shorter than other reported values in whole fixed tissue, which may be due to prolonged perfusion with a crystalloid buffer or inconsistencies in the cutting plane of our samples24,25,26,27.

a Representative images from experimental groups. b Images were analyzed for mitochondrial Feret diameter (N = 59 for normoxic, N = 70 for I/R + saline, and N = 62 for I/R + Elam), c matrix electron density (N = 59 for normoxic, N = 70 for I/R + saline, and N = 62 for I/R + Elam), and d cristae complexity index (N = 35 for normoxic, N = 30 for I/R + saline and I/R + Elam). *P < 0.05 v normoxic; #P < 0.05 versus I/R + Saline. Scale bar represents 2 µm.

Mitochondrial cristae complexity index was lowered after reperfusion (−46%), and this decrease in cristae complexity was attenuated with elamipretide by 36% (Fig. 2d). Cristae width averaged 25.0 ± 1.8 nm in normoxic mitochondria (N = 189) and was not influenced by I/R (cristae width: 25.4 ± 0.7 nm; N = 178) or elamipretide treatment (26.7 ± 0.5 nm; N = 172).

Higher resolution serial block-face scanning electron microscopy (SBF–SEM) was employed to obtain more advanced structural insight of cardiac mitochondria after I/R. These data are presented in Figs. 3 and 4 (along with reconstructed three-dimensional movies in Supplemental Movies 1–3). Under normoxic conditions, approximately 70% of cristae were physically adhered to the inner boundary membrane, termed “contact sites”. I/R injury led to a decrease (−37%) in the number of cristae contact sites (Fig. 3a, b; P < 0.05 versus normoxia). Post-ischemic administration of elamipretide blunted the loss of cristae adhered to contact sites (+23% versus I/R injury) (Fig. 3b; P < 0.05 versus I/R alone). Among adjoining mitochondria, intermitochondrial cristae network connectivity analysis indicated a substantial loss (−40%) in network connectivity between mitochondria after I/R (presented in Fig. 3c, d). Intermitochondrial cristae connectivity improved in post-ischemic hearts perfused with elamipretide by 24% (Fig. 3c, d).

Original SBF–SEM serial images were acquired and processed into 3D reconstructions using ImageJ (a). Mitochondria were then analyzed for contract site analysis (b) and intermitochondrial network connectivity (d), with quantified data in panels c and e, respectively. N = 6–8 for normoxic, N = 8 for IR + Saline/Elamipretide groups *P < 0.05 versus normoxic, #P < 0.05 versus I/R saline. Three-dimensional reconstructions of these images are presented in the Supplemental Figures, Fig. S5. Scale bar represents 500 nm.

Mitochondria were analyzed for cristae connectivity. a Top panel: individual slices from SBF–SEM imaging showing cristae networking. Middle panel: cross-section of composite stacks indicating networked (yellow) and orphaned cristae (red). Bottom panel: mitochondrial cross-section showing only networked cristae (from middle panel). Composition of total mitochondrial volume (b), total cristae volume (c), and connected cristae volume (d) were measured in each experimental groups. N = 10 for all groups. Scal bar represents 250 nm. *P < 0.05 versus normoxic; #P < 0.05 versus I/R.

Separate SBF–SEM analyses were conducted to determine the extent of intra-mitochondrial cristae network connectivity. In these studies, we attempted to map the connectivity of cristae inside a subset of mitochondria using the rationale that contiguous cristae facilitate efficient energy transfer. We termed cristae that were interconnected “networked cristae”, versus cristae that were disconnected from the network as “orphaned cristae”. From the analysis, we rendered networked cristae yellow and orphaned cristae red. These data are presented in Fig. 4 (with reconstructed three-dimensional movies in Supplemental Movies 4–6). Interestingly, in normoxic hearts 90% of all cristae appeared to be networked with one another (Figs. 4b–d and S7), 22% more matrix volume swelling, and a 22% loss of cristae volume occurred after reperfusion, which were not prevented with elamipretide (Fig. 4a–c). However, elamipretide increased the number of “connected cristae” by 10% versus cristae that were orphaned from the network (Fig. 4a, d). Furthermore, cristae that were reconstructed appeared tubular. In healthy mitochondria, cristae were often long, formed a lattice, and attached to the boundary membrane. These features are similar to the “finger-like” digitiform cristae structure as previously described28. Taken together, these data indicate that elamipretide did not prevent mitochondrial swelling or the loss of total cristae at reperfusion, but improved cristae contact sites with the boundary membrane and reticular connectivity among the cristae network.

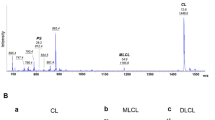

Mass spectrometry analyses of CL content and composition

The functional and structural importance of CL led us to conduct shotgun lipidomic studies for CL content and acyl chain composition. These data are presented in Fig. 5a, b, with the 20 most abundant CL species presented in Table 1. There was a 23% decrease in the total amount of CL after ischemia-reperfusion, as well as a 28% decline in the most abundant CL species (18:2-18:2-18:2-18:2) CL. The acute administration of elamipretide at the onset of reperfusion did not abrogate a reduction in CL content, the decrease in (18:2-18:2-18:2-18:2) CL species, or alter any of the other CL species examined (Fig. 5a, b and Table 1).

Lipidomics indicated declines in total (a) and tetra-linoleoyl CL (b) after ischemia-reperfusion. Biomimetic models of the mitochondrial inner membrane lipids presented in c–f. d GUV imaging of mitochondrial CL (NAO) and fluorescent TAMRA-elamipretide indicate elamipretide-mediated CL and vesicle aggregation (N = 3 experiments, 40–100 images per group). c Mean molecular area at physiological membrane pressure (30 mN/m) indicates consequences of losing CL content (N = 3–6 per group). Elamipretide augmented mean molecular area despite CL losses (modeled after the mass spectrometry data in panel a. More severe (50%) declines in total CL were also modeled. d Biomimetic membrane studies also determined effects of CL peroxidation and effects of elamipretide. f Proposed model in which elamipretide aggregates CL headgroups to increase mean molecular area. *P < 0.05 v control, #P < 0.05 v. I/R.

Biophysical studies of elamipretide

To better understand the biophysical interaction of elamipretide with cardiac mitochondrial membranes, we synthesized biomimetic membranes of the inner mitochondrial membrane. The model allowed us to tightly control lipid composition. Mitochondrial models were composed of biologically relevant lipids (see methods), and a CL content that represented 20% of the total lipids (consistent with content percentages seen across mammalian mitochondria29).

Informed by our CL lipidomic studies (Fig. 5a, b), we modeled the effects of decreased CL content after ischemia-reperfusion in biomimetic mitochondrial membranes by examining the biophysical interactions using a Langmuir trough (which provided mean molecular pressure-area isotherms of compressed lipid monolayers). A 25% reduction of CL content (“I/R model”) resulted in a 5% reduction in the mean molecular area at a physiological membrane pressure of 30 mN/m (Fig. 5c). Acute addition of elamipretide to I/R biomimetic membranes restored the mean molecular area in biomimetic monolayers with reduced CL (Fig. 5c) and oxidized CL (Fig. 5d). We also modeled severe reduction of CL content (50%, more comparable to some genetic mitochondrial diseases) and also saw a 7% improvement with elamipretide treatment versus I/R (albeit not restoring the area to the non-pathological membrane levels). Notably, elamipretide treatment of biomimetic monolayers without CL present had no discernible effect on membrane behavior (Fig. 5c, left panel).

To compliment the monolayer studies, we synthesized biomimetic mitochondrial lipid vesicles of similar composition. In the absence of peptide, CL fluorescence (assessed by nonyl acridine orange (NAO) localization) was uniform across the vesicle membrane and was accompanied by no observable aggregation of adjacent vesicles. Upon the addition of elamipretide to biomimetic vesicles, the NAO signal clustered into enriched domains. This CL clustering colocalized with fluorescent TAMRA-elamipretide (Fig. 5e), providing a complement to our imaging in intact cells (Supplemental Fig. 1). Furthermore, addition of elamipretide promoted aggregation of adjacent lipid vesicles (Fig. 5e) suggesting a potential mechanism of action (Fig. 5f). This aggregation effect was not seen in vesicles devoid of CL, and our previous work has shown that proteins that do not associate with CL do not have this effect on CL aggregation30.

Additionally, we serendipitously discovered that CL-containing vesicles and elamipretide eventually precipitated when in solution together (Supplemental Fig. 4). Titration studies indicated that elamipretide aggregated CL-enriched vesicles, essentially saturating the signal at a molar ratio of one peptide to two CL (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Discussion

This study advanced our understanding of mitochondrial structure-function in hearts exposed to ischemia-reperfusion. First, we found parallel decrements in mitochondrial cristae ultrastructure and respiratory function noted across electron transport system complexes after ischemia-reperfusion. Second, we used an innovative approach to map mitochondrial network connectivity in the heart, discovering decrements among and between mitochondrial cristae networks after ischemia-reperfusion. This aspect of our study employed the application of serial block-face scanning electron microscopy (SBF–SEM) to determine and quantify changes in mitochondrial cristae structure and connectivity in cardiac pathology. Third, the studies provided new mechanistic insight into elamipretide, a clinical-stage peptide that appears to aggregate CL and improve mitochondrial membrane structure and bioenergetic function without preventing the acute, reperfusion-induced decrease in CL content. Finally, we employed the use of biomimetic membranes to directly quantify membrane-dependent effects of pathologies and putative therapeutics.

The mitochondrial network is an attractive target for adjuvant therapies20,31. The factors that promote bioenergetic impairments include: reactive oxygen species production that exceeds endogenous scavenging capacity, matrix calcium overload, imbalances in substrate content/composition, inner membrane uncoupling, membrane lipid oxidation/degradation, inefficient electron flux, opening of energy-dissipating channels/pores, and collapse(s) in mitochondrial membrane potential (reviewed in refs. 8,32,33). A number of different pharmacological approaches have investigated the aforementioned factors, with several compounds progressing to clinical trials (reviewed in ref. 34). Our work advanced the field by showing that mitochondrial function could be improved by targeting decrements related to CL.

CL contributes to membrane structure by imparting negative membrane curvature35 at cristae junctions and along the inner leaflet of cristae membranes (depicted in Fig. 6). CL also serves as a membrane anchor for mitochondrial proteins essential for the cristae assembly/morphology, including ATP synthase dimers36,37,38,39,40, OPA140,41,42,43, mitoregulin44, and components of the mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system (MICOS)10,45,46,47,48,49. Although the role of proteins in influencing cristae structure cannot be understated, proton-dependent cristae formation was observed in membrane lipid vesicles devoid of any proteins50.

Preserved cristae integrity was associated with protection of complex V (red) band density. The other electron transport chain complexes are depicted in green, yellow, and purple (middle panel). Therapeutic approaches that target CL may conserve inner mitochondrial membrane integrity, maintain cristae contact sites, sustain intra and intermitochondrial networks, and improve mitochondrial function during disease states.

A reduction in the concentration of (18:2-18:2-18:2-18:2) CL that we observed was consistent with previous studies (refs. 12,16,51,52). Likewise, mitochondrial ultrastructural defects, similar to what we observed, are reported across other pathologies23 characterized by a decrease of CL concentration and corresponding cristae7. CL replacement strategies have been tested and include direct perfusion of CL to isolated rat hearts16 and utilization of CL-containing nanodiscs53. While promising, the translational relevance of these paradigms for patients remains to be demonstrated.

Our finding of multi-complex dysfunction after ischemia-reperfusion compliments previous studies noting decrements in complex activity, subunit oxidation, and augmented ROS production along the electron transport system33,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63. Mitochondria-targeting peptides represent an emerging class of therapeutics that are being tested across diseases. These peptides share structural homology with endogenous mitochondria-targeting sequences, which are both amphipathic and cationic64. Most mitochondria-targeting peptides contain alternating cationic-aromatic amino acid motifs17,65,66. Mitochondria-targeted peptides appear to be lipophilic enough to cross membrane barriers, typically contain arginine (especially the D-isomer for enzymatic stability), and are postulated to hone to mitochondria based on the negative membrane potential, the presence of anionic phospholipids (such as CL), or combinations thereof.

Elamipretide is a salt-variant of the SS-31 peptide first serendipitously discovered by Szeto and Schiller67 in their search for opioid receptor ligands. This peptide showed protective efficacy across preclinical studies (reviewed in refs. 8,19). Improved post-ischemic respiratory function with elamipretide was observed across complexes, in agreement with previous studies where elamipretide improved activity or expression of several different electron transport complexes15,68,69,70. These data suggest that elamipretide’s mechanism of action does not depend on one particular protein or complex. The improved bioenergetic function across complexes was suggested by studies examining the existence of native protein complexes. Supercomplex coupling control factor71, a functional measure of the ‘intactness’ of respirasomes, and native complex V structure were both impaired after ischemia-reperfusion and improved with elamipretide (Supplemental Fig. 2D, E). Although the functional significance of improved complex V density was not directly tested, the mitigation of electron transport chain dysfunction observed with elamipretide suggests the peptide may lessen decrements in ATP production previously observed after I/R72. We did not find evidence of a robust decrease in supercomplex band density after ischemia-reperfusion. These results are consistent with other studies examining supercomplexes after acute cardiac ischemia-reperfusion73,74, which generally show modest effects of ischemia-reperfusion on supercomplex band density. These findings also corroborated previous work where cardioprotection was not associated with augmented supercomplex band density75. Given the sensitivity of native protein complexes to detergent conditions74,76,77 and the issue of sample bias in isolating mitochondrial supercomplexes from infarcted myocardium (i.e., isolation procedures enrich for healthy mitochondria), future studies are warranted to better understand the relevance of blue-native supercomplexes in models of cardiac pathology.

The SS-31 peptide was originally described as a “scavenger” of reactive oxygen species. While it is clear that elamipretide can reduce overall ROS levels from pathological mitochondria (refs. 15,78, and Fig. 1 herein), several lines of evidence suggest that it is not scavenging ROS. We previously showed that the peptide was not scavenging either superoxide or hydrogen peroxide using cell-free model systems18. Other groups reported that elamipretide-mediated reductions in ROS are observed in diseased tissues but not healthy tissues68,79, also suggesting that the peptide may be reducing pathological production of ROS and not scavenging per se. Preconditioning of the heart, which has been shown to involve small bursts of ROS that trigger adaptive responses and is typically abolished with “ROS scavengers”, was not abolished with elamipretide80. Our finding of reduced ROS emission in permeabilized ventricular fibers and a modest reduction in RET81 provides further evidence that the peptide may be reducing succinate-derived RET early in reperfusion. Interestingly, elamipretide-mediated reductions in ROS production by the electron transport chain (ETC) were not observed downstream of ubiquinone (Fig. 1), suggesting an alternative mechanism than one involving cytochrome c-mediated injury21,82.

We observed interactions between elamipretide and CL, confirming findings first made by Birk et al.21,82. Among endogenous proteins, cationic amino acid residues are known to associate with CL44. Results from our microscopy studies with NAO and elamipretide colocalization suggest the peptide interacts with CL, which we speculate was driven by the cationic amino acids. We acknowledge that a limitation of our work is the use of a simplified biomimetic model system that lacks proteins. Future studies will require the incorporation of differing proteins into biomimetic membranes. An additional potential limitation of our work could be the use of imaging, which could introduce artifacts during sample preparation and analyses. Therefore, future studies will need to effectively integrate imaging, biochemical, and biophysical approaches.

Acute elamipretide treatment at reperfusion did not prevent the loss in CL content observed after acute ischemia-reperfusion. While longer term administration of elamipretide (>4 weeks) normalized aberrant CL in canine models of heart failure15 and pigs with metabolic syndrome70, our data indicated that the peptide has acute activity to preserve mitochondrial structure-function even in the presence of CL deficiencies. This beneficial activity suggests that the peptide may be effective in diseases characterized by a reduction of CL concentration (such as genetic mitochondrial diseases and/ or Barth syndrome [BTHS]).

The lowering or oxidation of CL modeled after ischemia-reperfusion led to a discernible change in the membrane structure (Fig. 5). Elamipretide promoted a physical ‘aggregation’ of CL molecules where the peptide is acting like a membrane adhesion factor for the CL that is present (even if it is oxidized). As it is difficult to study mammalian mitochondria devoid of CL, our finding that elamipretide-mediated lipid aggregation is not present without CL highlights the preferential nature of this interaction.

The nature of the physical aggregation between CL and elamipretide remains to be studied in the future. One approach would be to use fluorescently labeled CL to understand its complex relationship with the peptide; however, it will be critical to demonstrate that fluorescently labeled CL shows the same biophysical properties as native CL, which is unlikely to be the case due to the presence of bulky fluorescent groups. Additional studies are needed to understand the nature of the physical interaction of CL with the peptide as a function of changes in surface pressure. Our experiments relied on 30 mN/m as this is the gold standard in the field for biological relevance; however, surface pressure in the inner mitochondrial membrane likely varies with curvature and matrix swelling. To the best of our knowledge, the surface pressure as a function of cristae curvature remains to be established but is an important area for study.

The finding of improved mitochondrial ultrastructure with elamipretide in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury agrees with previous work where elamipretide improved mitochondrial morphology in other diseases70,82,83. We specifically provide insight into mitochondrial structure using higher resolution, SBF–SEM, which is an imaging approach capable of creating high-resolution 3D images that provide quantitative data on mitochondrial cristae morphology. The technical operation is also less demanding than other imaging approaches for performing volume analyses (i.e., serial section TEM and focused ion beam SEM), and SBF–SEM analysis is within the capabilities of many labs that lack previous EM experience84. The relationship between changes in mitochondrial morphology and functional outcomes remains unclear as reported here and by others85. Therefore, there is a critical need to further understand how modest changes in morphology could be driving key changes in the biophysical properties of the inner mitochondrial membrane to control respiratory function, an area for future investigation.

The finding that cristae contact sites were disrupted in the post-ischemic heart compliment altered contact sites seen in other diseases86,87. Elamipretide did not prevent the loss in total cristae with reperfusion (Fig. 4c), consistent with a lack of protection against decreased CL content (Table 1 and Fig. 5a, b), as these are inter-related50,88. A major advancement using this technology was that elamipretide partially restored the cristae network connectivity. This may help explain the protection of ATP synthase dimers with elamipretide, as ATP synthase and cristae architecture have shown interdependent declines in other pathologies38. However, more studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis as we did not specifically study the interdependence of cristae shape and ATP synthase. The modest reduction in RET we observed was also associated with improved cristae ultrastructure. Accordingly, it might be hypothesized that succinate accumulation induces RET, which has been associated with mitochondrial fragmentation89.

If any generalizations can be made about elamipretide’s mechanism across studies, it is that this peptide appears to exert biological effects predominantly when there is an underlying pathological burden present. In these cases, it tends to ‘normalize’ mitochondrial function that is dysfunctional prior to elamipretide exposure. The ability of elamipretide to prolong PTP opening15,18, improve exercise capacity79, promote CL remodeling15,70, reduce apoptotic signaling90, stimulate state 3 respiration21, or improve the activity of several different ETC complexes15,68,69,70 is only observed in diseased, aged, or damaged (respiratory control ratio <2) mitochondria. There appears to be translational support for this concept, as a recent clinical trial with elamipretide showed the greatest 6-min-walk benefit in patients who began the study with the largest functional impairments91.

A clinical trial using elamipretide in first time ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients did not reduce infarct size92. Exclusion of ~40% of the patient population due to patent arteries at the time of reperfusion, and group differences in baseline characteristics may have influenced the results. As we and others have recently noted, a number of factors likely to contribute to lack of translation in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion paradigms34,93.

As the sequence of elamipretide contains two non-natural amino acids, there is no known homology between this peptide and endogenous assembly or mitochondrial fusion factors, although the upregulation of cristae assembly factors (such as OPA1) has been recently observed after elamipretide treatment94,95. Given the cationic and aromatic repeats, and the fact that many mitochondrial assembly proteins have conserved RYL or RYK motifs44,96,97,98, it is tempting to speculate that the peptide is acting as an enzymatically resistant, cell-permeable analog of an endogenous assembly factor(s). Such a mechanism may explain why there are little/no observable effects in healthy mitochondria across studies with elamipretide as noted above. Healthy inner membranes may be sufficiently intact such that the addition of an adhesion factor has a negligible effect. This type of mechanism may also promote the utility of this peptide (and related analogs) across mitochondrial pathologies that share the commonality of structural abnormalities3,4. Clearly further testing is warranted to better elucidate the efficacy of elamipretide across other pathologies.

Our study provides insight into mitochondrial structure-function derangements in acute ischemia-reperfusion by combining functional measurements in mitochondria, fibers, and the intact heart, with new imaging modalities examining cristae architecture. Results indicate that while elamipretide does not prevent the reduction of CL concentration, post-ischemic treatment can improve functional and morphological characteristics of mitochondria even with decreased CL content. These characteristics include improved electron transport chain complex respiration, decreased H2O2 production, increased mitochondrial density, increased cristae connectivity, enhanced cristae networking within and between mitochondria, and finally, improved inner membrane integrity. The use of biomimetic models has profound potential to expand our understanding of the consequences of phospholipid alterations. Future studies utilizing these approaches will advance the development of mitochondria-targeting strategies.

Methods

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (aged 2–3 months) were used in the study. All procedures received prior approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at East Carolina University, Latvian Animal Protection Ethical Committee of Food and Veterinary Service, and Virginia Tech. Animals were housed in a temperature and light-controlled environment and received food and water ad libitum. Prior to excision of the heart, animals received an intraperitoneal (ip) injection of a ketamine/xylazine solution (90 mg/kg/10 mg/kg, respectively), and hearts were excised following the diminution of animal reflexes via midline thoracotomy and placed in ice-cold saline.

Materials

All phospholipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. Elamipretide and the TAMRA-elamipretide conjugate were synthesized by New England Peptide. All organic solvents were HPLC grade and all other reagents were purchased from either Fisher Scientific or Sigma.

I/R and respirometry of permeabilized ventricular fibers

Excised hearts were perfused on one of four modified Langendorff apparatus (AD Instruments) per our established protocols99,100. Hearts were exposed to 20/120 min of global ischemia/reperfusion, respectively. For the elamipretide treatment, hearts received 10μM elamipretide beginning at the onset of reperfusion, which is a well-established cardioprotective paradigm in our models18,78,80,101. Myocardial oxygen consumption was measured at the end of reperfusion in a subset of hearts per our established protocols102. At the end of reperfusion, hearts were split into the experimental groups described below. Two different protocols were employed to determine mitochondrial function after ischemic stress in ventricular muscle fibers. The first set determined mitochondrial function in fibers isolated after cardiac ischemia- reperfusion (“Post I/R Studies”). The second set of studies isolated cardiac fibers from a freshly isolated (normoxic) heart, and then induced anoxia-reoxygenation on the isolated fibers (“A/R Studies”). Detailed methods for the fiber studies are provided in the Methods Supplement. Below (Supplemental Fig. 5) is an overview of the permeabilized experimental flow.

Isolated mitochondria and BN-PAGE

Mitochondria were isolated from the left ventricle and succinate-derived reverse electron transport determined using our established protocols103. Detailed protocols for the separation of native mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes by BN-PAGE are described in the Methods Supplement. Supercomplex flux control coupling factor was measured as described97.

Electron microscopy of mitochondria

A subset of hearts exposed to ischemia-reperfusion (as described above) were utilized for transmission electron microscopy imaging (Virginia Tech Morphology Service Core Laboratory, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine) using modifications to established protocols104,105. Serial block-face scanning electron microscopy was done in collaboration with Renovo Neural, Inc. (Cleveland, Ohio). Detailed methods are provided in the Methods Supplement.

Mass spectrometry

A subset of hearts was taken immediately at the end of reperfusion and the left ventricle was snap frozen, pulverized using a liquid nitrogen-cooled mortar/pestle, and analyzed for CL content and composition using shotgun lipidomics per our established methods106. Detailed protocols for the mass spectroscopy studies are provided in the Methods Supplement.

Construction of biomimetic membranes

A detailed description of the methods for biophysical CL aggregation studies are provided in the Methods Supplement. Pressure-area isotherm experiments were performed using differing biomimetic lipid compositions. For pressure-area isotherms displayed in Fig. 5c, biomimetic mitochondrial lipid monolayers were generated by co-dissolving 40 mol% (18:0-22:6) PC, 30.0 mol% (16:0-20:4) PE, 20 mol% (18:2-18:2-18:2-18:2) CL, 5 mol% (18:1-18:1) PI, 3 mol% (18:1-18:1) PS, and 2 mol% cholesterol in chloroform (10 μg/μL) per our established methods107. Pressure-area isotherms displayed in Fig. 5d relied on biomimetic monolayers containing 40 mol% (18:0-22:6) PC, 33.0 mol% (16:0-20:4) PE, 20 mol% (18:2-18:2-18:2-18:2) CL, 5 mol% (18:1-18:1) PS, and 2 mol% cholesterol in chloroform (10 μg/μL). The area per molecule was determined at a physiological surface pressure of 30 mN/m as previously shown108. Giant unilamellar vesicles were constructed via electroformation as previously described30 and contained 39.9 mol% (18:0-22:6) PC, 30.0 mol% (16:0-20:4) PE, 20 mol% (18:2-18:2-18:2-18:2) CL, 5 mol% (18:1-18:1) PI, 3 mol% (18:1-18:1) PS, 2 mol% cholesterol, and 0.1 mol% NAO. For select experiments, the total CL concentration was decreased 25-50% by mass to reflect changes seen from mass spectroscopy studies. In a subset of studies peptide was added immediately after spotting the lipid monolayer or prior to imaging.

Statistics and reproducibilty

All data were analyzed using and GraphPad Prism 8 and are presented as mean ± sem. Data were distributed normally, which allowed for parametric analyses. Statistical analyses were conducted using a one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc, with P-values ≤ 0.05 considered significant. One trace from RET studies was excluded because the hydrogen peroxide emission was greater than two standard deviations away from the mean.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

References

Hackenbrock, C. R. Ultrastructural bases for metabolically linked mechanical activity in mitochondria. I. Reversible ultrastructural changes with change in metabolic steady state in isolated liver mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 30(2), 269–297 (1966).

Hackenbrock, C. R. Ultrastructural bases for metabolically linked mechanical activity in mitochondria. II. Electron transport-linked ultrastructural transformations in mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 37(2), 345–369 (1968).

Mannella, C. A. Structural diversity of mitochondria: functional implications. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1147, 171–179 (2008).

Mannella, C. A., Lederer, W. J. & Jafri, M. S. The connection between inner membrane topology and mitochondrial function. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 62, 51–57 (2013).

Glancy, B. et al. Mitochondrial reticulum for cellular energy distribution in muscle. Nature 523(7562), 617–620 (2015).

Schlame, M. & Ren, M. The role of cardiolipin in the structural organization of mitochondrial membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788(10), 2080–2083 (2009).

Chicco, A. J. & Sparagna, G. C. Role of cardiolipin alterations in mitochondrial dysfunction and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292(1), C33–44 (2007).

Brown, D. A. et al. Mitochondrial inner membrane lipids and proteins as targets for decreasing cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Pharm. Ther. 140(3), 258–266 (2013).

Schlame, M. & Greenberg, M. L. Biosynthesis, remodeling and turnover of mitochondrial cardiolipin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1862(1), 3–7 (2017).

Wollweber, F. et al. Mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system: a central player in membrane shaping and crosstalk. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1864(9), 1481–1489 (2017).

Kim, J. et al. Cardiolipin: characterization of distinct oxidized molecular species. J. Lipid Res. 52(1), 125–135 (2011).

Paradies, G. et al. Role of cardiolipin peroxidation and Ca2+ in mitochondrial dysfunction and disease. Cell Calcium 45(6), 643–650 (2009).

Sparagna, G. C. et al. Quantitation of cardiolipin molecular species in spontaneously hypertensive heart failure rats using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Lipid Res. 46(6), 1196–1204 (2005).

Chatfield, K. C. et al. Dysregulation of cardiolipin biosynthesis in pediatric heart failure. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 74, 251–259 (2014).

Sabbah, H. N. et al. Chronic therapy with elamipretide (MTP-131), a novel mitochondria-targeting peptide, improves left ventricular and mitochondrial function in dogs with advanced heart failure. Circ. Heart Fail 9(2), e002206 (2016).

Paradies, G. et al. Decrease in mitochondrial complex I activity in ischemic/reperfused rat heart: involvement of reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin. Circ. Res. 94(1), 53–59 (2004).

Horton, K. L. et al. Tuning the activity of mitochondria-penetrating peptides for delivery or disruption. Chembiochem 13(3), 476–485 (2012).

Brown, D. A. et al. Reduction of early reperfusion injury with the mitochondria-targeting peptide bendavia. J. Cardiovasc. Pharm. Ther. 19(1), 121–132 (2013).

Szeto, H. H. Pharmacologic approaches to improve mitochondrial function in AKI and CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28(10), 2856–2865 (2017).

Brown, D. A. et al. Expert consensus document: mitochondrial function as a therapeutic target in heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 14(4), 238–250 (2016).

Birk, A. V. et al. Targeting mitochondrial cardiolipin and the cytochrome c/cardiolipin complex to promote electron transport and optimize mitochondrial Atp synthesis. Br. J. Pharm. 171(8), 2017–2028 (2013).

Acin-Perez, R. et al. Respiratory active mitochondrial supercomplexes. Mol. Cell 32(4), 529–539 (2008).

Vincent, A. E. et al. The spectrum of mitochondrial ultrastructural defects in mitochondrial myopathy. Sci. Rep. 6, 30610 (2016).

Korte, F. S. & McDonald, K. S. Sarcomere length dependence of rat skinned cardiac myocyte mechanical properties: dependence on myosin heavy chain. J. Physiol. 581(2), 725–739 (2007).

Bub, G. et al. Measurement and analysis of sarcomere length in rat cardiomyocytes in situ and in vitro. Am. J. Physiol Heart-C. 298(5), H1616–1625 (2010).

Cury, D. P. et al. Morphometric, quantitative, and three‐dimensional analysis of the heart muscle fibers of old rats: transmission electron microscopy and high‐resolution scanning electron microscopy methods. Microsc. Res. Tech. 76(2), 184–195 (2012).

Julian, F. J. et al. Sarcomere length-tension relations in living rat papillary muscle. Circ. Res. 37(3), 299–308 (1975).

Riva, A. et al. Structural differences in two biochemically defined populations of cardiac mitochondria. Am. J. Physiol Heart-C. 289(2), H868–H872 (2005).

Paradies, G. & Ruggiero, F. M. Age-related changes in the activity of the pyruvate carrier and in the lipid composition in rat-heart mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1016(2), 207–212 (1990).

Pennington, E. R. et al. Proteolipid domains form in biomimetic and cardiac mitochondrial vesicles and are regulated by cardiolipin concentration but not monolyso-cardiolipin. J. Biol. Chem. 293(41), 15933–15946 (2018).

Pell, V. R. et al. Moving forwards by blocking back-flow: the yin and yang of MI therapy. Circ. Res. 118(5), 898–906 (2016).

Walters, A. M. et al. Mitochondria as a drug target in ischemic heart disease and cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 111(9), 1222–1236 (2012).

Murphy, E. & Steenbergen, C. Mechanisms underlying acute protection from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiol. Rev. 88(2), 581–609 (2008).

Kloner, R. A. et al. New and revisited approaches to preserving the reperfused myocardium. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 14(11), 679–693 (2017).

Ikon, N. & Ryan, R. O. Cardiolipin and mitochondrial cristae organization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1859(6), 1156–1163 (2017).

Quintana-Cabrera, M. & Rigoni, S. Who and how in the regulation of mitochondrial cristae shape and function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 500, 94–101 (2018).

Manella, C. Structure and dynamics of the mitochondrial inner membrane cristae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763, 542–548 (2006).

Siegmund, S. E. et al. Three-dimensional analysis of mitochondrial crista ultrastructure in a patient with leigh syndrome by in situ cryoelectron tomography. Cell Press 6, 83–91 (2018).

Jayashankar, V. et al. Shaping the multi-scale architecture of mitochondria. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 38, 45–51 (2016).

Cogliati, S. et al., Mitochondrial cristae: where beauty meets functionality. Trends Biochemical Sciences 41, 261–273 (2016).

Cogliati, S. et al. Mitochondrial cristae shape determines respiratory chain supercomplexes assembly and respiratory efficiency. Cell 155, 160–171 (2013).

Ban, T. K. H. et al. Relationship between OPA1 and cardiolipin in mitochondrial inner-membrane fusion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1859(9), 951–957 (2018).

DeVay, R. M. et al. Coassembly of Mgm1 isoforms requires cardiolipin and mediates mitochondrial inner membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol. 186, 793–803 (2009).

Stein, C. S. et al. Mitoregulin: a lncRNA-Encoded microprotein that supports mitochondrial supercomplexes and respiratory efficiency. Cell Rep. 23(13), 3710–3720 e8 (2018).

Genin, E. C. et al. CHCHD10 mutations promote loss of mitochondrial cristae junctions with impaired mitochondrial genome maintenance and inhibition of apoptosis. EMBO Mol. Med. 8, 58–72 (2016).

Li, H. et al., Mic60/Mitofilin determines MICOS assembly essential for mitochondrial dynamics and mtDNA nucleoid organization. Cell Death Differ 23, 380–392 (2015).

Kozjak-Pavlovic, V. The MICOS complex of human mitochondria. Cell Tissue Res. 367, 83–93 (2017).

Jans, D. C. et al. STED super-resolution microscopy reveals an array of MINOS clusters along human mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110(22), 8936–8941 (2013).

Weber, T. A. et al., APOOL is a cardiolipin-binding constituent of the mitofilin/MINOS protein complex determining crisate morphology in mammalian mitochondria. PLoS ONE 8, e63683 (2013).

Khalifat, N. et al. Lipid packing variations induced by pH in cardiolipin-containing bilayers: the driving force for the cristae-like shape instability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808(11), 2724–2733 (2011).

Petrosillo, G. et al. Decreased complex III activity in mitochondria isolated from rat heart subjected to ischemia and reperfusion: Role of reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin. FASEB J. 17(6), 714–716 (2003).

Paradies, G. et al. Mitochondrial bioenergetics and cardiolipin alterations in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Implications for pharmacological cardioprotection. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 315(5), H1341–H1352 (2018).

Malhotra, K. & Alder, N. N. Reconstitution of mitochondrial membrane proteins into nanodiscs by cell-free expression. Methods Mol. Biol. 1567, 155–178 (2017).

Hardy, L. et al. Reoxygenation-dependent decrease in mitochondrial NADH:CoQ reductase (Complex I) activity in the hypoxic/reoxygenated rat heart. Biochem. J. 274(Pt 1), 133–137 (1991).

Maklashina, E. et al. Effect of anoxia/reperfusion on the reversible active/de-active transition of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) in rat heart. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1556(1), 6–12 (2002).

Maklashina, E. et al. Effect of oxygen on activation state of complex I and lack of oxaloacetate inhibition of complex II in Langendorff perfused rat heart. FEBS Lett. 556(1–3), 64–68 (2004).

Szczepanek, K. et al. Mitochondrial-targeted signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) protects against ischemia-induced changes in the electron transport chain and the generation of reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 286(34), 29610–29620 (2011).

Lesnefsky, E. J. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac disease: ischemia-reperfusion, aging, and heart failure. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 33(6), 1065–1089 (2001).

Lesnefsky, E. J. et al. Myocardial ischemia selectively depletes cardiolipin in rabbit heart subsarcolemmal mitochondria. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 280(6), H2770–8 (2001).

Weiss, J. N. et al. Role of the mitochondrial permeability transition in myocardial disease. Circ. Res. 93(4), 292–301 (2003).

Kumar, V. et al. Redox proteomics of thiol proteins in mouse heart during ischemia/reperfusion using ICAT reagents and mass spectrometry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 58, 109–117 (2013).

Chen, J. et al. Peptide-based antibodies against glutathione-binding domains suppress superoxide production mediated by mitochondrial complex I. J. Biol. Chem. 285(5), 3168–3180 (2010).

Chen, Y. R. et al. Mitochondrial complex II in the post-ischemic heart: oxidative injury and the role of protein S-glutathionylation. J. Biol. Chem. 282(45), 32640–32654 (2007).

Backes, S. & Herrmann, J. M. Protein translocation into the intermembrane space and matrix of mitochondria: mechanisms and driving forces. Front. Mol. Biosci. 4, 83 (2017).

Horton, K. L. et al. Mitochondria-penetrating peptides. Chem. Biol. 15(4), 375–382 (2008).

Kelley, S. O. et al. Development of novel peptides for mitochondrial drug delivery: amino acids featuring delocalized lipophilic cations. Pharm. Res. 28(11), 2808–2819 (2011).

Szeto, H. H. & Birk, A. V. Serendipity and the discovery of novel compounds that restore mitochondrial plasticity. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 96(6), 672–683 (2014).

Dai, W. et al. Bendavia, a mitochondria-targeting peptide, improves postinfarction cardiac function, prevents adverse left ventricular remodeling, and restores mitochondria-related gene expression in rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharm. 64(6), 543–553 (2014).

Zhao, H. et al. Peptide SS-31 upregulates frataxin expression and improves the quality of mitochondria: implications in the treatment of Friedreich ataxia. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 9840 (2017).

Yuan, F. et al. Mitochondrial targeted peptides preserve mitochondrial organization and decrease reversible myocardial changes in early swine metabolic syndrome. Cardiovasc. Res. 114(3), 431–442 (2018).

Chatfield, K. C. et al. Elamipretide improves mitochondrial function in the failing human heart. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 4(2), 147–157 (2019).

Kinugasa, Y. et al. Allopurinol improves cardiac dysfunction after ischemia- reperfusion via reduction of oxidative stress in isolated perfused rat hearts. Circulation 67, 781–787 (2003).

Gadicherla, A. K. et al. Damage to mitochondrial complex I during cardiac ischemia reperfusion injury is reduced indirectly by anti-anginal drug ranolazine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817(3), 419–429 (2012).

Jang, S. et al. Elucidating mitochondrial electron transport chain supercomplexes in the heart during ischemia-reperfusion. Antioxid. Redox Sign 27(1), 57–69 (2017).

Wong, R. et al. Cardioprotection leads to novel changes in the mitochondrial proteome. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 298(1), H75–91 (2010).

Wittig, I. et al. Blue native PAGE. Nat. Protoc. 1(1), 418–428 (2006).

Gomez, L. A. et al. Supercomplexes of the mitochondrial electron transport chain decline in the aging rat heart. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 490(1), 30–35 (2009).

Kloner, R. A. et al. Reduction of ischemia/reperfusion injury with bendavia, a mitochondria-targeting cytoprotective Peptide. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 1(3), e001644 (2012).

Siegel, M. P. et al. Mitochondrial-targeted peptide rapidly improves mitochondrial energetics and skeletal muscle performance in aged mice. Aging Cell 12(5), 763–771 (2013).

Frasier, C. R. et al. Redox-dependent increases in glutathione reductase and exercise preconditioning: role of NADPH oxidase and mitochondria. Cardiovasc. Res. 98(1), 47–55 (2013).

Chouchani, E. T. et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 515(7527), 431–435 (2014).

Birk, A. V. et al. The mitochondrial-targeted compound SS-31 re-energizes ischemic mitochondria by interacting with cardiolipin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24(8), 1250–1261 (2013).

Sweetwyne, M. T. et al. The mitochondrial-targeted peptide, SS-31, improves glomerular architecture in mice of advanced age. Kidney Int. 91(5), 1126–1145 (2017).

Mukherjee, K. et al. Analysis of brain mitochondria using serial block-face scanning electron microscopy. J. Vis. Exp. 113, 54214 (2016).

Wei, L. et al. Dihydromyricetin ameliorates cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury through Sirt3 activation. Biomed. Res. Int. 6803943 (2019).

Frezza, C. et al. OPA1 controls apoptotic cristae remodeling independently from mitochondrial fusion. Cell 126(1), 177–189 (2006).

Glytsou, C. et al. Optic atrophy 1 is epistatic to the core MICOS component MIC60 in mitochondrial cristae shape control. Cell Rep. 17(11), 3024–3034 (2016).

Khalifat, N. et al. Membrane deformation under local pH gradient: mimicking mitochondrial cristae dynamics. Biophys. J. 95(10), 4924–4933 (2008).

Lu, Y.T. et al. Succinate induces aberrant mitochondrial fission in cardiomyocytes through GPR91 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 9, 672 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0708-5 (2018).

Nickel, A. G. et al. Reversal of mitochondrial transhydrogenase causes oxidative stress in heart failure. Cell Metab. 22(3), 472–484 (2015).

Karaa, A. et al. Randomized dose-escalation trial of elamipretide in adults with primary mitochondrial myopathy. Neurology 90(14), e1212–e1221 (2018).

Gibson, C. M. et al. EMBRACE STEMI study: a Phase 2a trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of intravenous MTP-131 on reperfusion injury in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur. Heart J. 37(16), 1296–1303 (2015).

Bøtker, H. E. et al. Translational issues for mitoprotective agents as adjunct to reperfusion therapy in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J. Cell Mol. Med. 24, 2717–2729 (2020).

Yin, X. et al. Mitochondria-targeted molecules MitoQ and SS31 reduce mutant huntingtin-induced mitochondrial toxicity and synaptic damage in Huntington’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25(9), 1739–1753 (2016).

Sabbah, H. N. et al. Abnormalities of mitochondrial dynamics in the failing heart: normalization following long-term therapy with elamipretide. Cardiovasc. Drug Ther. 32(4), 319–328 (2018).

Nicholls, D. G. and Ferguson, S. J. Bioenergetics. 4th edn. (Academic Press, London, 2013) pp. 297.

Na, U. et al. The LYR factors SDHAF1 and SDHAF3 mediate maturation of the iron-sulfur subunit of succinate dehydrogenase. Cell Metab. 20(2), 253–266 (2014).

Cory, S. A. et al. Structure of human Fe-S assembly subcomplex reveals unexpected cysteine desulfurase architecture and acyl-ACP-ISD11 interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114(27), E5325–E5334 (2017).

Brown, D. A. et al. Effects of 4′-chlorodiazepam on cellular excitation-contraction coupling and ischaemia-reperfusion injury in rabbit heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 79(1), 141–149 (2008).

Brown, D. A. et al. Cardiac arrhythmias induced by glutathione oxidation can be inhibited by preventing mitochondrial depolarization. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 48(4), 673–679 (2010).

Sloan, R. C. et al. Mitochondrial permeability transition in the diabetic heart: contributions of thiol redox state and mitochondrial calcium to augmented reperfusion injury. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 52(5), 1009–1018 (2012).

Liu, T. et al. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac glycoside toxicity. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 49(5), 728–736 (2010).

Dai, W. et al. Cardioprotective effects of mitochondria-targeted peptide SBT-20 in two different models of rat ischemia/reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 30(6), 559–566 (2016).

Fujioka, H. et al. Mitochondrial division in rat cardiomyocytes: an electron microscope study. Anat. Rec. 295(9), 1455–1461 (2012).

Lee, H. L. et al. Biphasic modulation of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 302(7), H1410–22 (2012).

Han, X. et al. Shotgun lipidomics of cardiolipin molecular species in lipid extracts of biological samples. J. Lipid Res. 47(4), 864–879 (2006).

Sullivan, E. M. et al. Docosahexaenoic acid lowers cardiac mitochondrial enzyme activity by replacing linoleic acid in the phospholipidome. J. Biol. Chem. 293(2), 466–483 (2018).

Pennington, E. R. et al. Distinct membrane properties are differentially influenced by cardiolipin content and acyl chain composition in biomimetic membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2(2017), 257–267 (1859).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support provided by Kathy Lowe of the Virginia Tech Electron Microscopy Core. We are also thankful for the contributions of Ella Maru Studio for professional illustrations used in Fig. 6 of our manuscript. These studies were supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health, NHLBI 1R01HL123647 (to S.R.S. and D.A.B.), R01HL141855 (to S.P.), R01HL102298 (to S.P.), R01HL138003 (to S.P.), P30DK056350 (to S.R.S.), Stealth BioTherapeutics (to D.A.B. and S.R.S.), USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch Project 1017927 (to D.A.B.), and a Translational Obesity Research Fellowship from the Virginia Tech Interdisciplinary Graduate Education Program (to M.E.A.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.E.A. and E.R.P. contributed equally to this work and assume first co-authorship. M.E.A., E.R.P., J.B.P., S.D., M.M.K., M.D., F.M., H.D.P., X.H., G.K.K., E.K.B., and T.B. performed experiments. M.E.A., E.R.P., S.P., S.R.S., and D.A.B. coanalyzed data and co-authored the manuscript. S.R.S. assumes final responsibility for the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.A.B. and S.R.S. have served as consultants for Stealth BioTherapeutics, which is developing elamipretide for clinical indications. After submission of this manuscript draft for review, D.A.B. transitioned from academia to full-time employment with Stealth BioTherapeutics. Accordingly, D.A.B. receives compensation and equity/shares commensurate with this employment. All other authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, M.E., Pennington, E.R., Perry, J.B. et al. The cardiolipin-binding peptide elamipretide mitigates fragmentation of cristae networks following cardiac ischemia reperfusion in rats. Commun Biol 3, 389 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-1101-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-1101-3

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.