Abstract

Epimutations are heritable changes in gene function due to loss or gain of DNA cytosine methylation or chromatin modifications without changes in the DNA sequence. Only a few natural epimutations displaying discernible phenotypes are documented in plants. Here, we report natural epimutations in the cadastral gene, SUPERMAN(SUP), showing striking phenotypes despite normal transcription, discovered in a natural tetraploid, and subsequently in eleven diploid Arabidopsis genetic accessions. This natural lois lane(lol) epialleles behave as recessive mendelian alleles displaying a spectrum of silent to strong superwoman phenotypes affecting only the carpel whorl, in contrast to semi-dominant superman or supersex features manifested by induced epialleles which affect both stamen and carpel whorls. Despite its unknown origin, natural lol epialleles are subjected to the same epigenetic regulation as induced clk epialleles. The existence of superwoman epialleles in diverse wild populations is interpreted in the light of the evolution of unisexuality in plants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Arabidopsis thaliana hermaphrodite (bisexual) flower consists of four concentric whorls of floral organs: outer (first) whorl composed of four sepals, second whorl with four petals, third, male reproductive whorl with six stamens and the innermost (fourth), female reproductive whorl consisting of two fused carpels forming a single bicarpellary pistil. A cohort of genes with distinct spatiotemporal expression in the floral meristem (FM) ensures an orderly establishment of the floral whorls1. The SUPERMAN is one such gene that encodes a C2H2 zinc finger domain containing transcription factor regulating floral homeotic genes during Arabidopsis flower development2,3,4. The SUP is essential for demarcating the floral boundary between the stamen and carpel whorls, FM termination, carpel-placenta boundary specification, and ovule integument differentiation3,4,5,6,7,8. SUPERMAN function is regulated both at genetic and epigenetic levels, as demonstrated by the identification and characterization of several genetic mutants and induced epimutants (clark kent(clk) epialleles) with varying phenotypic consequences. Based on the phenotypic variations in sexual boundary distortions in the reproductive whorls and FM indeterminacy, sup (epi)mutants have been classified as (i) superman (whorl 3 indeterminacy leading to male flowers with supernumerary stamens at the expense of carpels), (ii) superwoman (whorl 4 indeterminacy producing more than two carpels, with unaffected stamen whorl), and (iii) supersex (both whorl 3 and whorl 4 indeterminacy producing supernumerary stamens and carpels)6.

Epialleles arise due to methylation of cytosines in a gene loci without any change in the DNA sequence9. In animals, the cytosine methylation is mostly confined to symmetric CG context, with some exceptions10,11. Whereas in plants, it occurs in all sequence contexts: CG, CHG (H = A, T, C), and CHH12. Epimutations, natural or induced, add a new layer of heritable variation in addition to natural genetic polymorphisms existing in the germplasm, influencing many plant traits13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 and may have a role in adaptive evolution21. However, only a limited number of natural epimutations with phenotypic consequences are reported in the plant kingdom22,23. The resultant phenotypes in those natural epimutants are attributed to cytosine methylation of the regulatory (promoter) regions that negatively affect the transcription of the respective gene loci, resulting in either a total loss or reduced mRNA levels24. The clk epialleles of SUP are the first characterized induced epimutations in A. thaliana, whose genetic locus is shown to harbor methylated cytosines in all three sequence contexts25. Unlike natural epimutants, epigenetic regulation of SUPERMAN is atypical in that the methylated cytosines are seen predominantly in the transcribed regions of the loci rather than to its regulatory regions25. In the well-characterized induced sup epiallele clk-3, the superman phenotype is attributed to a reduction in the levels of mRNA25, whereas in some induced sup epialleles, no reductions in mRNA are observed despite DNA hypermethylation6 suggesting complex epigenetic regulation of the SUP gene.

In plants, the de novo methylation of genomic loci is established by siRNA mediated RNA dependent DNA methylation pathway (RdDM)26, whose molecular machinery consists of a multitude of proteins such as plant-specific RNA polymerases Pol IV and Pol V, DICER-LIKE 2 (DCL2), ARGONAUTE4 (AGO4), DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASE 2 (DRM2)12,27. DRM2 recruited to the corresponding loci by the RdDM machinery methylates the cytosines. Once established, methylated cytosines at CG context is maintained by DNA METHYLTRANSFERASE (MET1 aka DNMT in humans)28,29, while DRM2, CHROMOMETHYLASE 2 (CMT2), and CHROMOMETHYLASE 3 (CMT3) control methylation at CHG and CHH contexts in a partially redundant and locus-specific manner30,31,32,33. The DNA methyltransferases CMT2 and CMT3 are recruited to regions enriched for H3K9Me, which is methylated by a histone methyltransferase KRYPTONITE (KYP) in a self-reinforcing feedback loop linking both DNA and histone methylation34. In fact, SUP epimutants played a crucial role in discovering CMT3, KYP, and AGO4 genes as being extragenic suppressors of clk epimutations31,35,36. Unlike CMT3 and KYP, mutations in methyltransferases DRM1, DRM2, MET1, and the chromatin remodeler DECREASE IN DNA METHYLATION 1 (DDM1) are not required for maintaining the methylation at SUP locus37,38. The prevailing model for SUP locus methylation deciphered based on the study of induced (clk) epialleles suggest that AGO4 guides KYP to SUP chromatin to methylate H3K9, which creates a binding platform for LIKE HETEROCHROMATIN PROTEIN 1 (LHP1), which in turn recruits CMT3 catalyzing the methylation of cytosines at SUP locus, converting the SUP WT allele to clk epiallele36. Thus, the methylation of SUP locus in epimutants is independent of the RdDM pathway where the recruitment of the DRM2 mediates DNA methylation.

Intriguingly, SUP locus is unusual in the preponderance of induced epialleles (n = 12) in comparison to genetic alleles (n = 6) reported for any gene loci in A. thaliana (Supplementary Table 1). Despite these reports, no instance of natural epialleles has been discovered to date. Here, we report the existence of natural SUP epialleles in 12 of the 1028 core germplasm accessions (representing the global genetic diversity in A. thaliana) examined, mostly displaying superwoman phenotypes in contrast to superman phenotypes observed in induced epialleles, further deepening the mystery behind epigenetic regulation of SUP. We interpret the predominance of natural superwoman epialleles of SUPERMAN in the wild populations in the context of the evolution of unisexuality in flowering plants.

Results

Phenotypic characterization of superwoman inflorescences in the natural tetraploid Wa-1 Arabidopsis accession

The species A.thaliana prevails in the wild as diploid; however, rare tetraploid populations do exist39. One such tetraploid accession(4x = 2n = 20, x = basic chromosome number 5), Warschau-1 (Wa-1, CS22644) caught our attention because of its striking heterogeneity in the inflorescence phenotypes displaying a mix of normal bilocular siliques, unusual multilocular siliques, and curly siliques (Fig. 1a–g). The phenotype is 100% penetrant (n = 1080 plants) but with variable expressivity between individuals. We broadly classified the plants (n = 1080) into three categories based on the inflorescence phenotype: (i) plants with inflorescences predominantly displaying multilocular siliques (56%; Fig. 1a), (ii) plants with more curly siliques (9.5%; Fig. 1b), and (iii) plants with a random distribution of all types in varying proportions (34.2%; Fig. 1c). Overall, up to 63% (n = 3402/5400) of the siliques are multilocular than normal (n = 864/5400,16%), with remaining being curly (n = 1134/5400, 21%). To check whether these inflorescence phenotypes are transmitted true to type, we harvested seeds from each category and scored for the transmissibility of the respective phenotypes in the immediate progeny. Irrespective of the category, we observed all the three types of inflorescence reappearing in random proportions, suggestive of variable expressivity, however, with 100% penetrance (Supplementary Table 2).

a–c Representative images of inflorescence types observed in the tetraploid (4x) Wa-1 population. a An inflorescence with super fertile multilocular siliques. b An inflorescence consisting only of curly pistils/siliques. c An inflorescence containing a random distribution of both multilocular and curly siliques. d Representative images of a Wa-1 normal silique arising from a bicarpellary WT pistil, a multilocular silique originating from a pistil with supernumerary carpel and a developmentally arrested curly pistil/silique. e–g A transverse section of a bicarpellary (e), tricarpellary (f), and a tetracarpellary (g) silique from Wa-1 plants. Arrowheads indicate replum. h, i Matured siliques from normal (h) and multilocular (i) Wa-1 split open to reveal its anatomy. Normal silique shows two placental arrays of seeds attached to either replum surrounded by two carpel valves (h). Multilocular silique shows four placental arrays of seeds on a multiple repla surrounded by four carpel valves (i). j Replum-septum skeletons of individual siliques post dehiscence depicting multiple irregular replums and abnormal fusion of septum in multilocular siliques (numbered 1, 2, 3) to the normal one having two parallel replums interconnected by a continuous membranous septum (numbered 4). k Box and whisker plot showing seed count/silique from random (n = 20) normal, multilocular and curly siliques, respectively. The seed set is statistically significant (p < 0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis test, 2df, α = 0.05), Dunn’s posthoc test for three pairwise comparisons are also statistically significant with p values as indicated. l A partially fused (arrowhead) tetracarpellary pistil posing a folded fingers like phenotype. m Unfused tetracarpellary pistil showcasing two partially fused bicarpellary pistils embracing each other. n Congenital fusion of stamen to improperly fused carpel. o A stamen (arrowhead) arising from the carpel tissues. p Proliferative mass of apical stigmatic like tissues seen on the median portion of the carpel. q Sepal-like leafy outgrowth in carpels. r A flower originating from carpel tissues. s WT flower from the diploid Col-0 accession. t A superwoman flower from the tetraploid Wa-1 accession. u WT flower shown in s dissected to reveal six stamens and a bicarpellary pistil(arrowhead). v The superwoman flower shown in t dissected to reveal six stamens and a tetracarpellary pistil (arrowhead). w Wa-1 ploidy series consisting of haploid (x), diploid (2x), triploid (3x), and tetraploid (4x) individuals showing Wa-superwoman phenotypes (red arrowhead—multilocular siliques, blue arrows—curly siliques). Scale bar: a–c = 1 cm, d–t = 1 mm.

A closer inspection of the multilocular siliques revealed that they had more than two fused carpels. The phenotype was more apparent in the transverse sections (Fig. 1e–g), matured siliques (Fig. 1h, i), and in the replum–septum skeleton of dehisced siliques (Fig. 1j). A typical WT silique consists of two replums, a contiguous membranous septum joining two replums, two placental arrays of seeds originating on the inner sides of either replum, and two valves protecting the seeds (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 1). In contrast, the multilocular siliques contained more than two replums, two or more discontinuous septum’s, three or more placental arrays of seeds, and multiple carpel valves (Fig. 1i, j and Supplementary Fig. 1). Despite these silique patterning defects, the seed set in the multilocular siliques was not only normal but super fertile (hence superwoman) with 69–121 seeds/silique (n = 20) in contrast to its normal (WT) counterpart containing 52–64 seeds/silique (n = 20) (Fig. 1k). The curly siliques are due to abnormal fusion of supernumerary carpels (Fig. 1l, m) and are either sterile or partially fertile with 2–21 seeds/silique (n = 20). In some pistils, we observed organ fusion defects (Fig. 1n), and various homeotic transformations, as shown in Fig. 1o–r and they remained sterile without any seeds. Taken together, the phenotypes observed in Wa-1 (hereafter Wa-superwoman) are indicative of a floral homeotic transformation, explicitly affecting the fourth(carpel) whorl, with no visible phenotypes on the remaining three whorls of the flower (Fig. 1s–v). We also confirmed similar phenotypes in several other Wa-1 germplasm stocks CS28805, CS39006, CS6885, and CS1586 available at Arabidopsis Biological Resource Centre (ABRC). Hence, we conclude that the Wa-superwoman phenotype is characteristic of the Wa-1 genotype with an underlying genetic cause affecting floral organ patterning.

Genetic mapping and complementation identifies SUPERMAN as the causative locus behind Wa-superwoman phenotype

To unequivocally identify the locus, we employed a map-based cloning approach. However, the generation of a mapping population in the Wa-1 tetraploid is challenging due to the complex tetrasomic segregation of alleles. Hence, for mapping and subsequent genetic experiments, we used Wa-1 diploid (2x) derived from the Wa-1 tetraploid using CenH3 based genome elimination system40. To this end, we confirmed the penetrance and reproducibility of the Wa-superwoman phenotypes in the derived diploid population of Wa-1 plants (n = 950, 100% penetrance, Supplementary Fig. 2). In addition, we also observed identical inflorescence phenotypes in all haploid (1x) plants (n = 41) and triploid (3x) Wa-1 plants (n = 62), implying that the phenotype is independent of gene or genome dosage (Fig. 1w).

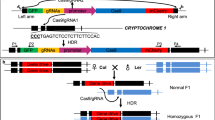

To generate a mapping population, we first crossed the derived diploid Wa-1 to WT Col-0 and Ler accessions. Irrespective of the accessions, all tested F1 progeny (n = 120) showed normal pistil and siliques that were indistinguishable from the WT, indicating the recessive nature of the locus (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Since Col-0 is more polymorphic to Wa-1 than Ler accession, we advanced the Wa-1 × Col-0 F1’s to F2 generation for subsequent mapping. In the F2 population, the phenotype segregated in a 3:1(394 WT:126 Wa-superwoman χ2 = 0.083, 1 df, p = 0.77) Mendelian ratio confirming its monogenic recessive nature. Next, we genotyped the F2 segregants showing the Wa-superwoman phenotype using genome-wide SSR markers (Supplementary Fig. 3b) and identified a marker MSAT3.19 in the third chromosome tightly linked to the phenotype (n = 90/100 plants homozygous for Wa-1 polymorphism). Among the genes located in the mapped region, we chose the SUP locus (~566 kb from MSAT 3.19) as a promising candidate due to the Wa-superwoman’s phenotypic resemblance with floral phenotypes exhibited by superman mutants6,41. At the DNA sequence level, except for a single nucleotide polymorphism (G to A) at 300 bp upstream of the SUP start codon, Wa-1 SUP locus (6.7 kb complementing region) was otherwise indistinguishable from WT Columbia (Col-0) reference sequence (TAIR 10). Hence, we converted this single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) as a dCAPS (derived Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequences) marker42, and genotyped the F2 segregants showing the Wa-superwoman phenotype and found the SNP to be co-segregating (100%, n = 100) with the phenotype, suggesting that SUP is the causative locus (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

To further validate that the identified gene locus is SUP, we performed two genetic tests: an allelism test by crossing a homozygous recessive sup-5 deletion mutant (displaying supersex phenotype) with Wa-1 diploid and showed that all the F1 plants (n = 93) had the otherwise recessive superwoman phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 4a), proving their allelic nature. Similar is the case in the F1 progeny harboring different heteroallelic combinations: Wa-1 allele with clk-3 epiallele (n = 24, Supplementary Fig. 4b) and Wa-1 allele with sup-2 truncated allele (n = 15, Supplementary Fig. 4c). Secondly, the genetic complementation test: a 6.7 kb genomic clone containing the SUP locus inserted elsewhere in the sup genetic and epigenetic mutants is shown to complement the sup mutation2,25. Hence, we cloned the corresponding region from Wa-1 harboring the SNP and introduced it into a sup-5 mutant and tetraploid Wa-1 plants, and found that it completely rescues the mutant to WT phenotype in all the T1 plants examined both in sup-5 (n = 8) and Wa-1 tetraploid (n = 7, Supplementary Fig. 4d). We observed similar WT phenotypes when the corresponding Col-0 genomic SUP WT locus was introduced into the tetraploid Wa-1 plants (n = 11, Supplementary Fig. 4d). Altogether, this rules out DNA sequence change (SNP) in the SUP locus as the cause of the Wa-superwoman phenotype.

DNA methylation analysis identifies lois lane (lol) natural epiallele of SUPERMAN in Wa-1

Given, there are no genetic alterations in the Wa-1 SUP genomic region, and the locus is known to be hypermethylated in induced epialleles, we examined its methylation status in the diploid Wa-1 plants by bisulfite sequencing. We found that a stretch of the Wa-1 SUP transcribed region (−282 to +776) was hypermethylated (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig. 5), similar to that of induced clk epialleles of SUP25,41. This was further validated by Chop PCR, an assay integrating the use of methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes (MSRE) with PCR to detect the methylation state of any genomic locus19,43,44. We chose a densely methylated region (patch-2) in SUP locus (Fig. 2a, c) in a way that it contains at least one cleavage site for two complementary MSREs: 1. McrBC (cleaves within the patch if any methylcytosine is preceded by a purine (A/G) on one or both the strands when two such sites are separated by a distance of 40–3000 bp) and 2. Dde1 (protects the patch from cleavage when cytosine is methylated in its recognition sequence 5′CTNAG3′). As expected, McrBC completely cleaved the region resulting in no PCR amplification with the primers flanking patch-2 region, whereas Dde1 protected the same part from cleavage resulting in PCR amplification in comparison to unmethylated Col-0 control consistent with the presence of methylated cytosines at Wa-1 SUP locus (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 13a). The faint PCR signal observed in the Dde1 digest may be suggestive of heterogeneous methylation of that cytosine residue in the cells of the inflorescence tissue. Taken together, we have discovered a natural epiallele of SUP, which we named as lois lane (lol-1), after the fictional superwoman comic character (in coherence with the naming convention of artificially induced clk epialleles of SUPERMAN after Clark Kent character). Although the gene body of SUP locus is hypermethylated, its methylation pattern is distinct from the gene body methylated (gbM) loci. Unlike canonical gbM loci enriched for CG methylation21, SUP epialleles are biased to high CHG and CHH methylation with negligible CG methylation in its gene body (Fig. 2e). Such methylation patterns are characteristic of transposon element methylation (teM) loci21. However, we didn’t find any unique transposable elements specific to Wa-1 SUP locus in its vicinity, at least ~50 kb in either direction, as the DNA sequence is identical to the unmethylated Col-0 genome except for a few SNPs. A majority of the methylated cytosines are common to clk and lol-1 epialleles (~80%, Supplementary Table 3) except for a few, especially in the patch-2 region and others being scattered throughout the locus (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5). Other than this, we didn’t find any characteristic methylation patterns unique to lol-1 epiallele in comparison to clk induced epialleles to explain the differences in the phenotype. Even between the induced clk epialleles that show a spectrum of superman to supersex phenotypes, epiallele specific methylation patterns cannot be ascertained41. It is attributed to mosaic methylation patterns that may vary among the cells of a tissue41. In conformity with this study, we do find heterogeneity in the methylation patterns in lol-1 locus ascertained from our high throughput whole-genome bisulfite genome sequencing data and Chop PCR assay (Fig. 2d). Intriguingly, the induced (clk) epialleles show semi-dominance in F1 and revert to WT at a low frequency25 whereas lol-1 natural epiallele behaves as a typical mendelian recessive allele, and no revertants were observed among the plants (n = ~1200) tested. The lol-1 epiallele affects only the carpel whorl with normal stamen whorl in contrast to induced clk epialleles, affecting both stamen and carpel whorls to varying degrees6.

a A cartoon representation of the hypermethylated SUP transcribed region. The numbers depict the nucleotide sequence’s relative position with reference to adenine nucleotide in ATG start codon of SUP gene as +1. b Methylation status of all cytosines present in the SUP transcribed region read from the bottom (5′ UTR) to top (3′ UTR). Individual cytosine methylation profiles for 17 genotypes are shown in the order as in e: Col-0 as unmethylated control, clk-1, clk-3, AMT (antisense methyltransferase1) induced sup epialleles as methylated controls (data for the figure is extracted from Fig. 325, 2x Wa-1(our high throughput sequencing data, two biological replicates), 12 natural accessions including Wa-1 (2n = 4x) are from the 1001 epigenomes project21. The cytosine methylation data for these 12 accessions are extracted from the 1001 epigenomes database. (+) for the sense strand and (−) for the antisense strand. Methylated and unmethylated cytosines are color-coded, as shown in the legend. White boxes indicate cytosines which didn’t have enough coverage to call it methylated or not. The symbols at the beginning of each column indicate the sup natural epiallele’s phenotypic strength displayed by the respective accession, as shown in the legend. An expanded view of figure panel b, is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5 for better clarity. c Cartoon representation of SUP locus depicting the patch-1 and patch-2 region and corresponding flanking primers(forward and reverse arrows) used for dCAPS assay and Chop PCR. d Chop PCR assay for patch-2 in unmethylated Col-0 control and Wa-1 (2x) using complementary MSRE: McrBC and Dde1. e A bar graph showing the % of cytosines methylated in different sequence contexts for the 17 genotypes represented in b. The individual accessions are shown on the x-axis, and the y-axis represents the % of methylated cytosines. Each genotype is represented by four vertical bars. The first bar represents the % of overall cytosines methylated at SUP transcribed region spanning −282 to +869 (1151 bp), consisting of 445 cytosines in total from both + and − strands. Overall there are 366 cytosines in CHH context, 55 in CHG context, and 24 in CG context in the transcribed region. The remaining three bars represent % of cytosines methylated, respectively, at CG, CHG, and CHH (where H = C, A, T) context. The phenotypic strength of natural epialleles (strong, moderate, and weak Wa-superwoman phenotypes) is roughly proportional to the % of cytosines methylated as indicated.

Identification and characterization lol epialleles displaying silent to strong superwoman phenotypes in geographically distinct natural diploid accessions

To examine whether hypermethylation of the SUP locus is unique to tetraploid Wa-1 accession, we analyzed the methylation landscape of the same locus in 1028 global collections of A. thaliana natural accessions sequenced in 1001 epigenome project21. Here, we identified 11 additional diploid accessions showing varying degrees of DNA methylation in SUP locus (Fig. 2b, e and Supplementary Fig. 5). Among them, the Geg-14 accession (lol-2) displayed phenotypes reminiscent of superwoman, supersex, and superman, all in one inflorescence (100% penetrance; Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 6), with the former two phenotypes being predominant (Fig. 3a–f); in nine accessions, (lol-3 to lol-11, Table 1), though a first glimpse gave an impression of WT phenotypes, a closer silique by silique inspection revealed mild lol phenotypes (Fig. 3g–k and Supplementary Fig. 6). However, the phenotype is restricted only to few siliques in the inflorescence of some, but not all the plants suggesting low penetrance and expressivity (Table 1). In one accession (Basta-2), consistent with mild methylation, we failed to detect any visible inflorescence phenotypes (Fig. 3l) and thus designated it as a silent SUP epiallele (lol-12). The hypermethylation state of the SUP locus in the natural accessions identified from the 1001 epigenomes project was further corroborated by Chop PCR assay. In five accessions (Wa-1, Geg-14, IP-Trs-0, LIN S-5, and Got-22), there was no PCR amplification of the McrBC digested DNA template in patch-2 consistent with McrBC cleaving these hypermethylated regions. However, in the remaining seven accessions, we observed fainter PCR amplification in the digested DNA template compared to the corresponding undigested controls and digested unmethylated Col-0 control (Fig. 3m and Supplementary Fig. 13b). It suggests that at least this region of SUP locus may be heterogeneously methylated in these accessions, consistent with the manifestation of moderate to silent lol phenotypes. Similar and complementary results were obtained for the other MSRE, Dde1 (Fig. 3n and Supplementary Fig. 13c). Overall, we find that the more the number of methylated cytosines, the higher the penetrance and vice versa (Fig. 2e and Table 1).

a A representative Geg-14 accession inflorescence depicting a spectrum of sup phenotypes: superwoman (blue arrowhead), superman (red arrow), and curly siliques(red asterisk). b A flower from Geg-14 inflorescence with supersex phenotype. c Dissected third and fourth whorls of the flower b respectively showing nine anthers and three carpels. d A flower from Geg-14 inflorescence with superman phenotype e dissected third and fourth whorls of the flower shown in d, respectively, showing seven anthers and a pistillode (sterile pistil) as indicated by arrowheads. f Replum–septum skeletons of dehisced silique from Geg-14 showing multiple replums (red arrows) and abnormal fusion of septum (blue arrowheads). g A partial tricarpellary silique from IP-Trs-1 plant. h The silique shown in g is split open to reveal its anatomy. The silique is bicarpellary and normal (red arrow) at the start, however in the midway, one of the repla bifurcates (blue arrowhead) to produce a partial tricarpellary silique (three carpel valves are shown). i–k The spectrum of replum–septum skeleton phenotypes from various accessions (as indicated) that show weak superwoman phenotypes. l Replum-septum skeleton from the SUP silent Basta-2 accession showing WT phenotypes. m Chop PCR assay in the natural accessions with hypermethylated SUP locus using the McrBC enzyme. The strong lol epialleles from Wa-1, Geg-14, and the moderate lol epialleles from IP-Trs-0 and the weak lol epiallele from Got-22 are fully methylated at cytosines at McrBC recognition sites, as they are PCR negative for the primers flanking patch-2. The remaining accessions show a faint PCR signal compared to their respective undigested controls suggestive of heterogeneous methylation of cytosines at this site. n Chop PCR assay in the natural accessions using the Dde1 enzyme. The strong lol epialleles from Wa-1, Geg-14, and the weak lol epialleles from Got-22 and Sorbo contain either fully or partially methylated cytosines at Dde1 recognition sites, as they are PCR positive for the primers flanking patch-2. The remaining accessions are PCR negative suggestive of the absence of cytosine methylation at this site. DNA markers used in the gels is 50 bp NEB ladder. Scale bars: a = 1 cm, b–l = 1 mm.

Suppression of DNA methylation by 5-Azacytidine is not sufficient to restore WT phenotypes in Wa-1

Genome-wide DNA methylation can be altered by treating A. thaliana with the drug 5-Azacytidine45,46. To examine whether Wa-1 plants exposed to 5-Azacytidine can restore WT inflorescence phenotypes by inducing loss of methylation at SUP locus, we germinated Wa-1 seeds in 5-Azacytidine medium (50, 75 µm) and continued the treatment by fertigation in the soil-grown plants. The treated seeds showed delayed germination, and the plants displayed altered flowering times, plant height, and less biomass compared to control Wa-1 plants concurring with the phenotypes of 5-Azacytidine exposed A. thaliana plants47. Upon flowering, we failed to detect any differences in the floral phenotypes between the 5-Azacytidine treated (n = 42) and control Wa-1 plants (n = 32)(Fig. 4a, b), further validated by Chop PCR (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 13d) suggesting that suppression of methylation by 5-Azacytidine is not sufficient to restore WT phenotype. This can be explained by the fact that 5-Azacytidine exerts its demethylating effect by interfering with the function of DNA methyltransferase MET148. It is known that MET1 is not required for maintenance of methylation at SUP locus38, in line with our observation that 5-Azacytidine has no effect on methylation at SUP locus.

a, b 5-Azacytidine treatment of Wa-1 plants does not suppress the silencing of lol-1 phenotypes. The Wa-1 (lol-1) floral phenotypes (from ~50-day old plants) are identical both in the untreated control (a) and 50 µm treated 5-Azacytidine plants (b). c Chop PCR assay with McrBC to confirm the SUP locus’s unchanged methylated state in 5-Azacytidine-treated plants. d, e Mutations in the histone methyltransferase KYP and DNA methyltransferase CMT-3 restore the WT phenotypes in lol-1 plants. Representative homozygous double mutant combinations of lol-1;kyp-2 (d) and lol-1;cmt3-7 (e) showing WT inflorescence phenotype in comparison to lol-1 plant. f–i Trans-chromosome methylation analysis in the F2 segregating population and the complemented tetraploid Wa1 plants. f Chop PCR(C) assay reveals the absence of trans chromosomal methylation in complemented tetraploid Wa-1 plants. Control 4x Wa-1 plants are C and dCAPS(D) assay negative, whereas 4x Wa-1 complemented plant with Col-0 SUP genomic locus is PCR positive only for Col-0 allele after C + D assay. The D assay alone on 4x Wa-1 complemented plant reveal heterozygosity with strong PCR signal for 4x Wa-1 allele consistent with its abundance (as indicated by asterisks) compared to the weak signal of ectopically inserted Col-0 clone (as indicated by arrowhead). g C and D assay in the patch-1 of SUP locus from representative F2 progeny from Wa-1 × Col-0 segregating population. Plants(#9,#23) displaying WT phenotype show Col-0 unmethylated allele both in D and C + D assay (190 bp fragment), indicating they are homozygous for Col-0 allele. Plants (#18, #63) displaying the Wa-1 inflorescence phenotype show Wa-1 unmethylated allele both in D and C + D assay (223 bp fragment), indicating they are homozygous for Wa-1 allele. Plants (#19, #27), display WT phenotype, but heterozygous in D (both 223 and 190 bp), and PCR positive only for uncut, unmethylated Col-0 allele after McrBC digestion. h, i C and D assay in the patch-2 of SUP locus from representative F2 progeny from Wa-1 × Sorbo F2 segregating population. Plants (#12, #28) display WT phenotype confirmed by D assay and C positive with McrBC digested template. Plants (#33,#66) display Wa-1 inflorescence phenotype, confirmed by D assay showing homozygosity for Wa-1 allele and C assay negative. Plants (#3,#20) display WT phenotypes, are heterozygous as revealed by D assay and C positive only for Col-0 allele. j A dot plot of Δct values representing SUP mRNA abundance, with respect to ACTIN2 as internal control in hypermethylated Wa-1 and Geg-14 accessions, compared to unmethylated WT Col-0 control (unpaired t-test (two-tailed) p = 0.76 (Col-0 and Wa-1), p = 0.09 (Col-0 and Geg1), ns non-significant, ɑ = 0.05). Six and four biological replicates for Wa-1 and Geg-14, respectively, were analyzed. k Semi-quantitative RT-PCR showing the abundance SUP mRNA and alternative splice variant in the control Col-0, and representative lol accessions. ACTIN2 is used as an internal control. Error bar = Standard deviation (SD) of biological replicates. DNA markers used in the gels is 50 bp NEB ladder. Scale bars: a, b = 2 cm; d, e = 1 cm.

Genetic mutations in CMT3 and KYP suppress Wa-superwoman phenotypes

Mutations in the DNA and histone methyltransferases, CMT3 and KYP respectively, are known to suppress clk phenotype by causing loss of CHG methylation at SUP locus in clk epialleles31,35. To check whether lol phenotypes are suppressed in a similar manner, we generated homozygous double mutants of lol-1;cmt3-7 (n = 4) and lol-1;kyp-2 (n = 6) combinations. All the double mutants displayed WT phenotypes (Fig. 4d, e), indicating that natural lol epiallele is subjected to the same epigenetic regulation as induced clk epialleles.

Natural genetic variation in known genes involved in SUP locus DNA methylation is not associated with superwoman (lol) phenotypes

To ascertain whether any natural genetic variation common to these 12 accessions correlates with methylation of SUP, we first screened the 1001 genome database for genetic polymorphisms in known candidate genes CMT3, KYP, and AGO4, that are directly involved in the methylation of SUP. Our analysis revealed no significant association linking SUP methylation with natural allele variations existing in these three genes (Supplementary Figs. 7, 8). Notably, the G to A SNP seen in the Wa-1 SUP locus is not linked with lol phenotypes. Despite showing lol phenotypes, the rest of the accessions (lol-2 to lol-12) lack this variant as inferred from the 1001 genome project and validated by dCAPS assay (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Next, we examined the possible link of CMT2, whose involvement is unknown in SUP locus methylation. CMT2-dependent pathway mediates the bulk of DNA methylation in CHH context, especially in the transposon-rich pericentromeric regions30,49. Genetic variation at CMT2 gene locus in natural accessions, especially the truncated cmt2STOP alleles, is shown to be significantly associated with decreased (~1%) genome-wide CHH methylation levels identical to cmt2 knockout mutants50,51. As the penetrance of different lol allele phenotypes is proportional to the number of cytosines methylated, and a notable number of cytosines in the SUP locus are in CHH context (Fig. 2b, e), we analyzed for the possible association of the natural variation at CMT2 locus in all of the 12 accessions harboring lol epialleles (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). Three of the twelve accessions (Geg-14, Sorbo, and Basta-2) contain the cmt2STOP allele (Supplementary Fig. 10a), which may be invoked to explain the reduced DNA methylation and weak penetrance of lol phenotypes observed in Sorbo (lol-7) and Basta-2 (lol-12) accessions. However, Geg-14 (lol-2) accession, which also harbors the truncated null allele, shows strong lol phenotypes with 100% penetrance. Hence, like other methyltransferase MET1, CMT2 is also not required for maintenance of SUP methylation. Besides, other lol accessions (for, e.g., Got-22, Ip-Mos-1, and Pla-0) with WT CMT2 allele also show a weak phenotype. Further, for reasons unknown, all cmt2STOP alleles (depending on the natural accessions) do not behave as null alleles50, suggesting natural variation at CMT2 locus in lol accessions is unlikely to be a major player in determining the strength of the lol epiallele. Finally, phylogenetic analysis using whole-genome SNP polymorphisms revealed that most of the SUP hypermethylated accessions are genetically distant and dispersed, suggestive of probable, multiple independent origins of hypermethylated SUP locus in diverse niches (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Stable meiotic transmission and absence of trans-chromosomal spread of DNA methylation between lol epialleles and WT alleles

In an F1 hybrid, a methylated allele can trigger trans spreading of the methylated state to an unmethylated allele by trans-chromosomal methylation52. Using a combination of dCAPS and Chop PCR in the Col-0 × Wa-1 F1 and F2 progeny, we show that the hypermethylated Wa-1 (lol-1) epiallele and unmethylated Col-0 SUP allele remain unaffected without any reciprocal transmethylation/demethylation effects. Retention of stable epigenetic states in F1 plants is consistent with the recessive behavior of lol-1 epiallele displaying a loss of lol-1 phenotypes in those hybrids (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The respective methylation states of the parental alleles were transmitted intact in the F2 progeny (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 13f), co-segregating with the mendelian phenotypic ratio of 3:1. We also observed similar results in another F2 population derived from a heteroallelic F1 hybrid carrying a strong (lol-1) and weak (lol-7) epialleles, respectively (Fig. 4h, i and Supplementary Figs. 12, 13g, h). Further, we also show that transgenic Col-0 SUP genomic locus that complements the lol phenotype in tetraploid Wa-1 plants also remain unmethylated (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 13e). These results, collectively, rule out trans-chromosomal spread of methylation between endogenous SUP alleles and ectopic transgenic locus.

SUP mRNA expression is unaltered in the lol natural epimutants showing superwoman phenotypes

To test whether hypermethylation of SUP locus causes a reduction in SUP mRNA levels as reported for clk-3 epiallele25, we carried out real-time qRT-PCR on the Wa-1 (lol-1) and Geg-14 (lol-2) accessions that showed strong Wa-superwoman phenotypes. Surprisingly, we didn’t find any changes in mRNA levels both in diploid Wa-1 and Geg-14 compared to unmethylated Col-0 control (Fig. 4j). Our results are in corroboration with an earlier study reporting no reduction in the mRNA levels in some of the induced sup epialleles6. We also failed to detect novel splice variants unique to lol accessions other than the one previously reported common to both WT and induced epimutants6 (Fig. 4k and Supplementary Fig. 13i, j). In the absence of no difference in total SUP mRNA levels between WT and lol epimutants, and SUP mRNA being expressed only in a narrow window of time, restricted to third and fourth whorls of the floral meristem3,4,5,6,7,8, it would be challenging to detect spatio-temporal quantitative fluctuations of mRNA, if any, by RNA in situ hybridization. This one of our limitations to account for the phenotypes in lol accessions despite similar WT mRNA levels. Besides, heterogeneous methylation of SUP locus among the cells also is a confounding factor that may or may not affect mRNA levels. Another post-transcriptional possibility to account for the phenotypes is the quantitative fluctuations in SUP protein levels despite normal levels of mRNA6 or SUP locus is partially transcribed, resulting in a truncated mRNA/protein. However, attempts to raise quality antibodies against SUP for immunolocalization studies remain unsuccessful6, making it challenging to address this hypothesis.

Discussion

In this study, we have identified an array of wild SUP epialleles (lol-1 to lol-12) with a spectrum of inflorescence phenotypes from 12 natural accessions spread across three different continents. These natural lol epialleles constitute a multiple SUP (epi)allelic series, along with known induced clk epialleles and mutant genetic alleles. As is the case with multiple alleles, we do observe a dominance hierarchy in the epiallelic series. The hierarchy is as follows: WT SUP(dominant) > weak lol epialleles > strong lol epialleles > strong clk alleles. In different cross combinations involving any two epialleles, the dominant epiallele expresses its phenotype in F1 and segregates in a mendelian fashion in the F2 generation (Supplementary Figs. 3, 4, 12). These lol epialleles behave as loss of function genetic alleles with stable meiotic transmission, at least for three generations studied. However, the lol epialleles show variable expressivity in the floral phenotypes in the absence of genetic heterogeneity within an accession. This can be attributed to stochastic, labile epigenetic states leading to mosaicism between the cells or between different individuals causing variable phenotypic expression53 as observed in mammalian epialleles54,55.

It is not known what triggered the origin of these natural lol epialleles in certain wild accessions, but its stable maintenance and transmission require the action of known molecular players of SUP methylation such as KYP and CMT3 methyltransferases. The establishment of de novo DNA methylation is effected by siRNA mediated RNA dependent DNA methylation pathway56. However, siRNAs from SUP locus have not been detected either in WT or clk epimutants36. Further, if DNA methylation is established through the siRNA mediated RdDM pathway, then there should be trans spreading of methylation from the hypermethylated epiallele to the unmethylated allele in F1 hybrids52,57 and the F2 segregants58,59 as well as in transgenic lines with the ectopic insertion of SUP locus. However, our results do not conform with this proposition, ruling out the involvement of SUP siRNAs in the DNA methylation of SUP locus36. We failed to find any significant association of natural variation for known genes involved in differential methylation of SUP locus, implying likely involvement of hitherto unknown factors controlling methylation of SUP locus in these accessions. Hence, the genomes of these natural lol epimutant accessions may hold a key towards unraveling the missing links in the epigenetic regulation of SUP.

An independent origin and prevalence of such natural epialleles of SUPERMAN in a dozen wild diploid and tetraploid populations cannot be ignored as stochastic events, but assumes significance when viewed in terms of the evolution of sex determination systems in plants. Based on the imperfect unisexuality phenotypes (superman vs. superwoman) manifested by allelic/epiallelic series of SUP, it is posited that alteration of the SUP or SUP-like genes is likely to be involved in the origin of flower bisexuality6. Orthologs of SUP/SUP-like genes from both diecious Silene latifolia and monecious Cucumis sativus are expressed only in female flowers, implying its involvement in sex determination by differential gene expression60,61. A flexible mechanism to achieve tissue-specific differential gene expression without altering the DNA sequence is by epigenetic alteration62. Such a mechanism underlying sex differentiation in flowering plants has been postulated63, and subsequently proven in persimmons and melon14,62. Unisexuality has evolved independently, multiple times in flowering plants, with wide variation between species implying different genetic basis and mechanisms64. Hence, we speculate that the origin of epialleles in the floral boundary gene, such as SUP, may be an early event in the evolutionary path towards unisexuality in specific flowering plant lineages. Notably, the SUP locus seems to be a vulnerable hotspot for epigenetic modification by hypermethylation, as revealed by the predominance of both artificially induced and natural epialleles (from this study) isolated for any gene loci in A. thaliana.

Interestingly, almost all natural lol epialleles (11/12) portray superwoman phenotypes. In striking contrast, most of the induced epialleles (10/12), are predominantly superman or supersex6, except for carpel41 and epi3A16. This suggests that natural epialleles have evolved towards altering later rather than early functions (before vs. after carpel meristem specification respectively) of SUP, thus confining the phenotype only to the carpel whorl giving rise to superwoman features. This observation calls into question why the preponderance of superwoman phenotypes in natural populations? We interpret this in terms of the enhanced reproductive fitness of superwoman over superman for its existence in the wild. A model for evolutionary transition from hermaphroditism to unisexuality predicts a two-step pathway65. The first step is to create females with a reproductive advantage over hermaphrodites, a system known as gynodioecy. In the second step, the males evolve by supplanting the hermaphrodites leading to dioecy. In this aspect, being a superwoman (super fertile) has a selective advantage over superman (which is sterile), at least in the early stages, to maintain the transmittance of altered epigenetic states until stable gynodioecy evolves in the lineage.

The epialleles from diploid accessions show mild hypermethylation and less penetrance than the densely hypermethylated tetraploid Wa-1 accession. The evolution of unisexuality is often associated with stable polyploidy in several plant genera65. The process of polyploidization, as a consequence, leads to a series of genetic, epigenetic changes, and chromosomal rearrangements66. Hence, we hypothesize that polyploidization event might trigger the transition of mild epigenetic states prevailing in the diploids to dense hypermethylated states causing stronger phenotypes in polyploids. The existence of such a metastable superwoman phenotype in one of the rarely existing natural tetraploid A. thaliana accession (Wa-1) supports this line of thought. It may be noted that our interpretation linking the existence of natural lol epialleles of SUP in wild populations with the evolution of unisexuality in plants is speculative, inferred based on existing literature, and thus requires further evolutionary studies to validate our conclusions.

In conclusion, we propose that the natural sup epialleles (lol series) captured here are likely to be evolutionary vestiges or transition intermediates in the early evolutionary path leading to unisexuality, at least, in the Arabidopsis lineage. In the family Brassicaceae, Lepidium sisymbrioides is the only known diecious polyploid sister genus to A.thaliana67. L. sisymbrioides have diverged relatively recently from A.thaliana lineage, and unisexuality (dioecy) has evolved as a result of selective abortion of reproductive whorls at the same floral developmental stage from a bisexual flower67. A possible role of SUP in the diminution of reproductive whorls of Lepidium has been contemplated68,69. Hence, it will be interesting to see epigenetic regulation of SUP, if any, in the evolution of dioecy in L. sisymbrioides.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Plants were grown in pots under fluorescent lights (7000 lux at 20 cm) at 20 °C with a 16 h light/8 h dark cycle at 70% RH in a controlled growth cabinet (Percival Inc.) or in walk-in growth rooms (Conviron). All the diploid natural accessions (CS 78917(Sorbo), CS78782(Cnt-1),CS77387(IP-Trs-0),CS77108(IP-Mos-1),CS77040(LIN S-5), CS76884(Got-22), CS76876(Geg-14), CS76616(Tscha-1), CS76573(Pla-0), CS76549(Me-0)), tetraploid Wa-1 accessions (CS22644, CS28805, CS39006, CS6885, CS1586) and superman mutants: sup-5(CS3882), flo10-1/sup-2(CS6225), clk-3(CS69095), cmt3-7(CS6365), kyp-2(CS6367) used in the study was obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC), Ohio State University (OSU). WT Col-0 and Ler stocks used in this study were a gift from Late Dr. Simon Chan, University of California, Davis. The Wa-1 ploidy series consisting of triploid (2n = 3x = 15), diploid (2n = 2x = 10) and haploid (2n = x = 5) plants were generated by CenH3-mediated genome elimination method as described40,70.

Microscopy and imaging

The siliques and flower phenotypes were examined either using Carl Zeiss Stemi 2000-C stereo zoom trinocular microscope or Leica M205 FA stereomicroscope. Images were captured using Zeiss Axiocam 105 or Leica DFC30 FX cameras attached to its respective microscopes. The inflorescence and whole plant images are captured using Canon 70D SLR camera. The images are edited either in Adobe Photoshop CS6 and Affinity Designer.

Phenotypic analysis of Wa-1 accessions

Several Wa-1 germplasm stocks (CS28805, CS39006, CS6885, CS1586) deposited by several independent research groups exist at ABRC, OSU. Hence, to ascertain whether the Wa-superwoman(lol-1) phenotype is limited to CS22644 stock, we grew ~50 plants each from all the four Wa-1 stocks and scored for the Wa-superwoman inflorescence phenotypes.

Genetic mapping of SUP locus

Using the TAIR polymorphism/allele search tool (www.Arabidopsis.org), a set of 53 genome-wide, evenly distributed polymorphic markers (SSR and indel) that can distinguish Wa-1 from Col-0 and Ler accessions were shortlisted. Upon experimental validation by PCR genotyping, 47 markers polymorphic between Col-0 and Wa-1 (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c), 33 markers between Ler and Wa-1 (Table S3). For segregation analysis of Wa-superwoman phenotypes, Wa-1 derived diploid was crossed to both Col-0 and Ler accessions. The resultant F1 hybrids were further confirmed by genotyping using a subset of validated polymorphic markers. For genetic mapping, seeds from self-pollinated Wa-1 × Col-0 F1 plants were pooled and advanced to raise an F2 segregating population. Out of 520 F2 progeny, 126 plants were found to show lol-1 phenotype. DNA was extracted individually from all the 126 plants for mapping the causative locus. For rough mapping, we employed bulk segregant analysis71 and identified a marker MSAT3.19 (physical coordinate 8808167) the q arm of the third chromosome that is tightly linked with the phenotype. Next, the MSAT 3.19 marker was genotyped individually in 100/126 F2 plants and found 89 plants homozygous for the Wa-1 allele, and the remaining 10 were heterozygous, confirming its proximity to the candidate locus. We chose SUP as the candidate locus for the reasons mentioned in the “Results” section.

For fine mapping, the SNP (G to A) in Wa-1 SUP locus is exploited to derive a PCR based dCAPS (derived Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequences) marker for distinguishing Wa-1 allele from Col-0/Ler allele. A set of primers (MR692 Forward: 5′TTTCTTTAAAGTTTCATTTTATTAAATCTCATAT 3′; MR693 Reverse: 5′AAGATCTGAAAAGATGAACTCAC3′) were designed to amplify a 223 bp fragment encompassing patch-1 of SUP locus (Fig. 2a, c) in a way that the forward primer generates a NdeI restriction site in combination with the Col-0 SNP but not with Wa-1 SNP. Hence, upon Nde1 restriction digest of 223 bp amplified product, the Wa-1 allele remains uncut, in contrast, the WT allele gets cut into 190 bp and 33 bp fragments, which can readily be distinguished by agarose (2.5%) gel electrophoresis.

Plasmid construction, plant transformation, and complementation analysis

The 6.7 kb SUPERMAN genomic region (corresponding to physical coordinates 8237177 to 8243854, TAIR 10), which complements the sup genetic as well as epigenetic mutation2,25, was PCR amplified from both WT Col-0 and Wa-1 accession with polymorphic SNP and cloned into pCAMBIA1300 as a SacI and PstI fragment using the following primer combinations; Forward: 5′gaacGAGCTCagctaccatattataatacg3′ and reverse: 5′gtaaCTGCAGtgcccttgtataggaattc3′. The resultant binary vector was then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain ASE by electroporation. The transgene construct was introduced into sup-5 recessive mutant and Wa-1 tetraploid by floral dip method. The seeds obtained from the transformed plants were plated onto a selection medium (1% KNO3 + 0.8% bacto agar + 50 µg/ml hygromycin), and the transformants were selected for hygromycin resistance a week after plating and then transferred to soil for further growth. The transformants were then genotyped to confirm the presence of Wa-1 SNP using the dCAPS marker.

For the allelism test, we crossed Wa-1 derived diploid as a female parent to sup-5 recessive (CS3882), flo10-1/ sup-2 (CS6225), and clk-3 (CS69095) as a pollen parent. The resultant F1 seeds were sown, and after flowering, the sup phenotypes were scored in the inflorescence of F1 plants.

Whole-genome sequencing and bisulfite sequencing analysis

The genomic DNA from Wa-1 derived diploid plants was isolated using DNA extraction plant kit (ORIGIN) from the tissues pooled from leaves and inflorescence of two independent plants (biological replicates). The genomic DNA was fragmented, end-repaired, and adapters were ligated to the DNA fragments, PCR amplified and sequenced by Illumina’s paired-end chemistry using Nextseq 500 at FASTERIS SA (Switzerland) and Eurofins Scientific (India). BBtools-BBduck v38.59 was used for the illumina adapter removal. FASTQC v0.11.7 was used for illumina reads quality check. BWA was used to map the illumina reads to the reference genome from TAIR10. In the case of bisulfite sequencing, adapter-ligated DNA fragments were bisulfite converted using EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen),

The de novo assembly of the diploid Wa-1 genome was done using SPAdes assembler. Blast analysis of the resulting contig revealed no structural variations within, and proximal to SUP gene except an SNP upstream in the promoter region identical to tetraploid Wa-1 sequence available at 1001 genomes project. The assembled contigs were compared with TAIR10 Col-0 reference for insertions and deletions using Assemblytics and the bed output was then analyzed for any insertion or deletion nearby SUP gene. To check for the presence of any unique transposons or transposon-like elements in the Wa-1 accession, we aligned the Col-0 reference genome sequence (TAIR10) with the assembled derived diploid Wa-1 sequence (our sequencing data) and with tetraploid Wa-1 sequence (1001 genomes project data) using Assemblytics1.2. The DNA sequences of the CMT2, CMT3, KYP, and AGO4 for the 12 accessions are extracted from the 1001 genome project. The sequences were aligned using MEGAX72 software.

In the case of bisulfite sequencing, DNA sequence 10 kb upstream and 5 kb downstream of the SUP gene from TAIR 10 was used as a reference to map the high quality reads using the Bismark package73. The raw BS-seq data were filtered using the AfterQC package74 to obtain high-quality reads. The clean reads were then mapped back to the C to T and G to A converted references using bowtie as the mapping tool. After removing clonal reads, the number of methylated and unmethylated reads along with their trinucleotide context was generated for each cytosine on both the strands. The bisulfite conversion efficiency, as calculated using lambda DNA, was 97.3%. The cytosine report from two biological replicates were merged and methylation call was performed. The cytosines with overall coverage equal or more than five were considered for methylation calling. The cytosine with five or above-methylated reads or more than 40% of the reads were considered as methylated. The data for cytosine methylation of accessions other than Wa-1 diploid is obtained from the 1001 epigenome project21. The whole-genome sequencing and bisulfite sequencing data for Wa-1 diploid is submitted to NCBI under the bio project accession PRJNA633425 consisting of three SRA accession identifiers: SRR12367310, SRR11805321, and SRR11805322.

Chop PCR analysis

The DNA from respective genotypes used in Chop PCR assay was extracted using the standard CTAB method. One microgram of DNA (as quantified by Colibri microvolume spectrometer) was digested with methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes McrBC and Dde1 (both from NEB Ltd) at a concentration of 10 units/µg of DNA template in a 30 µl reaction mix, for at least 6 h. After heat inactivation, 4 µl of the digested DNA was used as a template in a 20 µl reaction volume for PCR. Two densely methylated patches (Patch-1 and Patch-2) in SUP locus, as indicated in Fig. 2a, c is used for Chop PCR assay. Two MSRE’s, namely McrBC (cleaves the site if cytosine is methylated) and Dde1 (protects the site if cytosine is methylated), were chosen for Chop PCR assay. McrBC has at least one recognition site in both Patch-1 and Patch-2, whereas Dde1 has one site only in the patch-2.

For Chop PCR assay involving natural lol accessions, we chose patch-2 for analysis to use both complementing MSREs for the assay. The digested and undigested controls are PCR amplified using the primer combinations (MR860:5′CATGGCCACCAGATTACAC3′, MR862: 5′GTCTTACAAGCGTTTTCTGGTGTAT3′) spanning the patch-2 of SUP locus to give a 325 bp fragment on PCR amplification.

For trans chromosomal methylation experiments involving Wa-1 × Col-0 F2 segregants (Fig. 4g) and Wa-1 tetraploid complemented plants, we employed the dCAPS primer combination (MR692 and MR693) that span the patch-1 as described earlier for mapping experiments to distinguish Wa-1 (lol-1) allele from Col-0 SUP and other lol alleles. This dCAPS assay, when carried out in succession with McrBC digested DNA template helps to distinguish the methylated Wa-1 allele from the unmethylated Col-0 allele (Fig. 4g). However, in the case of Wa-1 × Sorbo F2 segregating population the dCAPS primer combination cannot be employed because both Wa-1 and Sorbo would be cleaved by McrBC, thus cannot distinguish either allele. To overcome this, we used another primer pair MR860 and MR862 (spanning the patch-2 region of SUP locus), which in combination with the McrBC digested DNA template, can distinguish the strong Wa-1 (lol-1) epiallele from weak (lol-7) Sorbo epiallele (Fig. 4h, i).

Scoring for superman phenotypic series

A flower is classified as superwoman if it has typical stamen whorl with six anthers and supernumerary fourth whorl with greater than two carpels; superman, if the flower has supernumerary stamens at least greater than seven with sterile, dysfunctional/reduced carpel; supersex, if the flower harbors more than six anthers and more than three carpels.

The phenotypes exhibited by natural epialleles are classified as strong if the phenotype shows at least greater than 70% penetrance; moderate, if the penetrance is between 40–70%; weak, if the penetrance is 1–40% and silent if it is less than 1%.

Double mutant analysis

Wa-1 diploid plants were crossed with homozygous cmt3-7 and kyp-2 as pollen parents. The segregating F2 progeny were genotyped using dCAPS markers for homozygosity of the Wa-1 SUP locus. The cmt3-7 and kyp-2 mutants were genotyped using the CAPS and dCAPS assay, respectively, using the primers as described31,35. The sequences of the primers are given in Table. S4.

5-Azacytidine treatment

Surface sterilized diploid Wa-1 seeds were placed in petri dishes containing filter papers soaked in 50 µm, 75 µm concentrations of 5-Azacytidine (Himedia Laboratories LLC), and water (control), cold stratified for 3 days at 4 °C. After cold treatment, the plates were transferred to the growth chamber for germination. Subsequently, the seeds were exposed to the respective concentrations of 5-Azacytidine for every alternate day till transfer to the soil medium. The surviving seedlings were then transferred to the soil medium imbibed with 0.5× MS solution containing the respective concentrations of 5-Azacytidine. After bolting, the inflorescences were sprayed once a week, thrice with respective concentrations of 5-Azacytidine.

Statistics and reproducibility

All the statistical analysis described in the study: the chi-square test for goodness of fit for genetic crosses, Kruskal–Wallis (KW) test for seed set data, two-tailed unpaired t-test for SUP mRNA quantitation was performed using GraphPad PRISM (v 8.4.2) statistical software. We employed the non-parametric KW statistical test, the parametric equivalent to one way ANOVA, for analyzing the seed numbers counted from different types of silique in Wa-1 inflorescence. The non-parametric KW test that is ideal for comparing medians of three or more groups was used here because seed numbers counted from multilocular siliques didn’t fit Gaussian distribution as determined by Shapiro–Wilk test (α = 0.05), an essential prerequisite for applying parametric statistical tests. Hence, we chose to summarize the data using the median rather than the mean. Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was performed as a posthoc test to analyze statistical significance between different groups of siliques.

SUP mRNA expression analysis

Inflorescence heads, a week to 10 days after bolting, were harvested and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated using HiPurA plant RNA extraction kit (HiMedia Laboratories, LLC) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. To remove the genomic DNA contamination, the RNA was treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (1U, Promega), for 45 min at 37 °C followed by heat inactivation of the enzyme at 75 °C for 15 min. One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using TAKARA Primescript RT reagent kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Oligo dT (17mer) primer was used for the first-strand cDNA synthesis. qPCRs were performed on a Mastercycler BIORAD CFX96TM using the primers (MR610 Forward: 5′TTTCTCCTCCATCCTCACCAAG3′; MR614 Reverse: 5′TAATCAAACCAATCTCAAGCTC3′) for SUP locus and primers (MR372 Forward: 5′TCGGTGGTTCCATTCTTGCTTC3′; MR373 Reverse: 5′TCTGTGAACGATTCCTGGACC3′) for ACT-2 control. The reactions were carried out using TAKARA TB green Premix Ex Taq 2 and incubated at 95 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 30 s. ACT-2 were used for the normalization of all the reactions. PCR specificity was checked by melting curve analysis. At least four independent biological samples were analyzed for each accession as indicated, and qPCR reactions were set up using three technical replicates from each biological replica. SUP mRNA abundance was analyzed using normalized Ct (Δct) values with ACT-2 as a reference gene.

For semi-quantitative RT-PCR and for checking the splice variants in SUP transcripts we used the forward primer MR866 (5′GTCTTACAAGCGTTTTCTGGTGTAT3′) located at the start of 5′UTR of SUP gene in combination with reverse primer MR 862 (5′GATATATCTTAGATTTTTCCAGGG3′) flanking the patch-2 of SUP locus with same PCR cycling conditions as described for Real-time PCR but only for 27 cycles. ACT-2 was used as an internal control. The resulting PCR products were resolved in a 2% agarose gel.

Phylogenetic analysis

The phylogenetic tree was constructed using 50 natural accessions: 12 with hypermethylated SUP locus identified in this study and the remaining 38 non-methylated accessions randomly selected from each geographic cluster as classified by 1001 genomes project. The SNP data for all the accessions were downloaded from the 1001 genomes website (https://1001genomes.org/data/GMI-MPI/releases/), and they were merged into a single VCF file using BCFtools. Using SNPhylo75, SNPs were filtered using default values except for the LD threshold which was set at 0.4. The filtered SNPs were collated as a sequence and used MEGA X72 for phylogenetic tree construction using Maximum likelihood and general time-reversible model (GTR + G) with 100 bootstraps.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The whole-genome sequencing and bisulfite sequencing data generated and analyzed during the current study are available from NCBI under the bio project accession PRJNA633425 consisting of three SRA accession identifiers: SRR12367310, SRR11805321, SRR11805322. All other source data are included in the article as supplementary data 1–5.

References

Krizek, B. A. & Fletcher, J. C. Molecular mechanisms of flower development: an armchair guide. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 688–698 (2005).

Bowman, J. L. et al. SUPERMAN, a regulator of floral homeotic genes in Arabidopsis. Development 114, 599–615 (1992).

Schultz, E. A., Pickett, F. B. & Haughn, G. W. The FLO10 gene product regulates the expression domain of homeotic genes AP3 and PI in Arabidopsis flowers. Plant Cell 3, 1221–1237 (1991).

Sakai, H., Medrano, L. J. & Meyerowitz, E. M. Role of SUPERMAN in maintaining Arabidopsis floral whorl boundaries. Nature 378, 199–203 (1995).

Gaiser, J. C., Robinson-Beers, K. & Gasser, C. S. The Arabidopsis SUPERMAN gene mediates asymmetric growth of the outer integument of ovules. Plant Cell 7, 333–345 (1995).

Breuil-Broyer, S., Trehin, C., Morel, P. & Boltz, V. Analysis of the Arabidopsis superman allelic series and the interactions with other genes demonstrate developmental robustness and joint specification of male–female boundary, flower meristem termination and carpel compartmentalization. Ann. Bot. 117, 905–923 (2016).

Prunet, N., Yang, W., Das, P., Meyerowitz, E. M. & Jack, T. P. SUPERMAN prevents class B gene expression and promotes stem cell termination in the fourth whorl of Arabidopsis flowers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 7166–7171 (2017).

Hiratsu, K., Ohta, M., Matsui, K. & Ohme-Takagi, M. The SUPERMAN protein is an active repressor whose carboxy-terminal repression domain is required for the development of normal flowers. FEBS Lett. 514, 351–354 (2002).

Oey, H. & Whitelaw, E. On the meaning of the word ‘epimutation’. Trends Genet. 30, 519–520 (2014).

Lister, R. et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature 462, 315–322 (2009).

Ramsahoye, B. H. et al. Non-CpG methylation is prevalent in embryonic stem cells and may be mediated by DNA methyltransferase 3a. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5237–5242 (2000).

Law, J. A. & Jacobsen, S. E. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 204–220 (2010).

Cubas, P., Vincent, C. & Coen, E. An epigenetic mutation responsible for natural variation in floral symmetry. Nature 401, 157–161 (1999).

Martin, A. et al. A transposon-induced epigenetic change leads to sex determination in melon. Nature 461, 1135–1138 (2009).

Manning, K. et al. A naturally occurring epigenetic mutation in a gene encoding an SBP-box transcription factor inhibits tomato fruit ripening. Nat. Genet. 38, 948–952 (2006).

Silveira, A. B. et al. Extensive natural epigenetic variation at a de novo originated gene. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003437 (2013).

Quadrana, L. et al. Natural occurring epialleles determine vitamin E accumulation in tomato fruits. Nat. Commun. 5, 3027 (2014).

Miura, K. et al. A metastable DWARF1 epigenetic mutant affecting plant stature in rice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 11218–11223 (2009).

He, L. et al. A naturally occurring epiallele associates with leaf senescence and local climate adaptation in Arabidopsis accessions. Nat. Commun. 9, 460 (2018).

Springer, N. M. & Schmitz, R. J. Exploiting induced and natural epigenetic variation for crop improvement. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 563–575 (2017).

Kawakatsu, T. et al. Epigenomic diversity in a global collection of Arabidopsis accessions. Cell 166, 492–505 (2016).

Weigel, D. & Colot, V. Epialleles in plant evolution. Genome Biol. 13, 249 (2012).

Johannes, F. & Schmitz, R. J. Spontaneous epimutations in plants. New Phytol. 221, 1253–1259 (2019).

Kalisz, S. & Purugganan, M. D. Epialleles via DNA methylation: consequences for plant evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 309–314 (2004).

Jacobsen, S. E. & Meyerowitz, E. M. Hypermethylated SUPERMAN epigenetic alleles in Arabidopsis. Science 277, 1100–1103 (1997).

Matzke, M. A. & Mosher, R. A. RNA-directed DNA methylation: an epigenetic pathway of increasing complexity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 394–408 (2014).

Mahfouz, M. M. RNA-directed DNA methylation: mechanisms and functions. Plant Signal. Behav. 5, 806–816 (2010).

Finnegan, E. J., Peacock, W. J. & Dennis, E. S. Reduced DNA methylation in Arabidopsis results in abnormal plant development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 8449–8454 (1996).

Ronemus, M. J., Galbiati, M., Ticknor, C., Chen, J. & Dellaporta, S. L. Demethylation-induced developmental pleiotropy in Arabidopsis. Science 273, 654–657 (1996).

Stroud, H. et al. Non-CG methylation patterns shape the epigenetic landscape in Arabidopsis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 64–72 (2014).

Lindroth, A. M. et al. Requirement of CHROMOMETHYLASE3 for maintenance of CpXpG methylation. Science 292, 2077–2080 (2001).

Bartee, L., Malagnac, F. & Bender, J. Arabidopsis cmt3 chromomethylase mutations block non-CG methylation and silencing of an endogenous gene. Genes Dev. 15, 1753–1758 (2001).

Cao, X. & Jacobsen, S. E. Locus-specific control of asymmetric and CpNpG methylation by the DRM and CMT3 methyltransferase genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 16491–16498 (2002).

Johnson, L. M. et al. The SRA methyl-cytosine-binding domain links DNA and histone methylation. Curr. Biol. 17, 379–384 (2007).

Jackson, J. P., Lindroth, A. M., Cao, X. & Jacobsen, S. E. Control of CpNpG DNA methylation by the KRYPTONITE histone H3 methyltransferase. Nature 416, 556–560 (2002).

Zilberman, D., Cao, X. & Jacobsen, S. E. ARGONAUTE4 control of locus-specific siRNA accumulation and DNA and histone methylation. Science 299, 716–719 (2003).

Cao, X. & Jacobsen, S. E. Role of the Arabidopsis DRM methyltransferases in de novo DNA methylation and gene silencing. Curr. Biol. 12, 1138–1144 (2002).

Jacobsen, S. E., Sakai, H., Finnegan, E. J., Cao, X. & Meyerowitz, E. M. Ectopic hypermethylation of flower-specific genes in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 10, 179–186 (2000).

Schmuths, H., Meister, A., Horres, R. & Bachmann, K. Genome size variation among accessions of Arabidopsis. Ann. Bot. 93, 317–321 (2004).

Ravi, M. et al. A haploid genetics toolbox for Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 5, 5334 (2014).

Rohde, A. et al. Carpel, a new Arabidopsis epi-mutant of the SUPERMAN gene: phenotypic analysis and DNA methylation status. Plant Cell Physiol. 40, 961–972 (1999).

Neff, M. M., Neff, J. D., Chory, J. & Pepper, A. E. dCAPS, a simple technique for the genetic analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms: experimental applications in Arabidopsis genetics. Plant J. 14, 387–392 (1998).

Zhang, H. et al. Protocol: a beginner’s guide to the analysis of RNA-directed DNA methylation in plants. Plant Methods 10, 18 (2014).

Dasgupta, P. & Chaudhuri, S. Analysis of DNA methylation profile in plants by Chop-PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 79–90, 2019 (1991).

Burn, J. E., Bagnall, D. J., Metzger, J. D., Dennis, E. S. & Peacock, W. J. DNA methylation, vernalization, and the initiation of flowering. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 287–291 (1993).

Bender, J. & Fink, G. R. Epigenetic control of an endogenous gene family is revealed by a novel blue fluorescent mutant of Arabidopsis. Cell 83, 725–734 (1995).

Bossdorf, O., Arcuri, D., Richards, C. L. & Pigliucci, M. Experimental alteration of DNA methylation affects the phenotypic plasticity of ecologically relevant traits in Arabidopsis. Evol. Ecol. 24, 541–553 (2010).

Raj, K. & Mufti, G. J. Azacytidine (Vidaza(R)) in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2, 377–388 (2006).

Zemach, A. et al. The Arabidopsis nucleosome remodeler DDM1 allows DNA methyltransferases to access H1-containing heterochromatin. Cell 153, 193–205 (2013).

Shen, X. et al. Natural CMT2 variation is associated with genome-wide methylation changes and temperature seasonality. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004842 (2014).

Dubin, M. J. et al. DNA methylation in Arabidopsis has a genetic basis and shows evidence of local adaptation. Elife 4, e05255 (2015).

Greaves, I., Groszmann, M., Dennis, E. S. & Peacock, W. J. Trans-chromosomal methylation. Epigenetics 7, 800–805 (2012).

Rakyan, V. K., Blewitt, M. E., Druker, R., Preis, J. I. & Whitelaw, E. Metastable epialleles in mammals. Trends Genet. 18, 348–351 (2002).

Morgan, H. D., Sutherland, H. G., Martin, D. I. & Whitelaw, E. Epigenetic inheritance at the agouti locus in the mouse. Nat. Genet. 23, 314–318 (1999).

Reed, S. C. The inheritance and expression of fused, a new mutation in the house mouse. Genetics 22, 1–13 (1937).

Matzke, M., Kanno, T., Huettel, B., Daxinger, L. & Matzke, A. J. M. Targets of RNA-directed DNA methylation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10, 512–519 (2007).

Greaves, I. K. et al. Trans chromosomal methylation in Arabidopsis hybrids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 3570–3575 (2012).

Greaves, I. K., Groszmann, M., Wang, A., Peacock, W. J. & Dennis, E. S. Inheritance of trans chromosomal methylation patterns from Arabidopsis F1 hybrids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 2017–2022 (2014).

Greaves, I. K. & Eichten, S. R. Twenty-four–nucleotide siRNAs produce heritable trans-chromosomal methylation in F1 Arabidopsis hybrids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 113, E6895–E6902 (2016).

Kazama, Y. et al. A SUPERMAN-like gene is exclusively expressed in female flowers of the dioecious plant Silene latifolia. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 1127–1141 (2009).

Zhao, J. et al. Cucumber SUPERMAN has conserved function in stamen and fruit development and a distinct role in floral patterning. PLoS ONE 9, e86192 (2014).

Akagi, T., Henry, I. M., Kawai, T., Comai, L. & Tao, R. Epigenetic regulation of the sex determination gene MeGI in polyploid persimmon. Plant Cell 28, 2905–2915 (2016).

Diggle, P. K. et al. Multiple developmental processes underlie sex differentiation in angiosperms. Trends Genet. 27, 368–376 (2011).

Ainsworth, C., Parker, J. & Buchanan-Wollaston, V. Sex determination in plants. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 38, 167–223 (1998).

Ashman, T.-L., Kwok, A. & Husband, B. C. Revisiting the dioecy-polyploidy association: alternate pathways and research opportunities. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 140, 241–255 (2013).

Chen, Z. J. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms for gene expression and phenotypic variation in plant polyploids. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 58, 377–406 (2007).

Soza, V. L., Le Huynh, V. & Di Stilio, V. S. Pattern and process in the evolution of the sole dioecious member of Brassicaceae. Evodevo 5, 42 (2014).

Bowman, J. L. & Smyth, D. R. Patterns of Petal and Stamen reduction in Australian species of Lepidium L. (Brassicaceae). Int. J. Plant Sci. 159, 65–74 (1998).

Bowman, J. L., Brüggemann, H., Lee, J. Y. & Mummenhoff, K. Evolutionary changes in floral structure within Lepidium L. (Brassicaceae). Int. J. Plant Sci. 160, 917–929 (1999).

Ravi, M. & Bondada, R. Genome elimination by tailswap CenH3: in vivo haploid production in Arabidopsis. Methods Mol. Biol. 1469, 77–99 (2016).

Michelmore, R. W. & Paran, I. Identification of markers linked to disease-resistance genes by bulked segregant analysis: a rapid method to detect markers in specific genomic regions by using segregating populations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 88, 9828–9832 (1991).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549 (2018).

Krueger, F. & Andrews, S. R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics 27, 1571–1572 (2011).

Chen, S. et al. AfterQC: automatic filtering, trimming, error removing and quality control for fastq data. BMC Bioinform. 18, 80 (2017).

Lee, T.-H., Guo, H., Wang, X., Kim, C. & Paterson, A. H. SNPhylo: a pipeline to construct a phylogenetic tree from huge SNP data. BMC Genom. 15, 162 (2014).

Acknowledgements

R.B. acknowledges Junior and Senior Research Fellowship for Ph.D. awarded by University Grants Commission, Govt. of India. M.A.B. is the recipient of the INSPIRE Scholarship for Higher Education awarded by Department of Science and Technology (Govt. of India). V.K.P. is a recipient of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research(CSIR)—Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Ph.D. fellowship. R.M. thanks financial support from Ramalingaswami re-entry fellowship awarded by the Department of Biotechnology (Govt. of India), and Dupont Young Professor grant, Dupont USA. We thank, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER)- Thiruvananthapuram, for intramural financial and infrastructural support. We thank Puneet Prabhakar Singh for help with the initial characterization of Wa-1 accession, Dilsher Singh Kulaar, for help with Wa-1 × Sorbo crosses, Dr. Ullasa Kodandaramaiah for discussion on phylogenetic analysis, and Dr. Kalika Prasad for sharing the cmt3-7 and kyp-2 seed stocks. We thank Prof. Luca Comai, UC Davis, for providing the facility for growing A. thaliana natural accessions and microscopy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M. conceptualized, designed, and supervised the study. R.B. contributed to certain aspects of the study design and carried out most of the experiments. M.P.M. contributed to the phenotypic analysis of accessions along with R.B. S.S. did the bioinformatics analysis of bisulfite sequencing data along with RB. M.A.B. performed the cloning experiments along with R.B. and partially contributed to the phenotypic screening. V.K.P. contributed to RT-PCR experiments. R.M. wrote the paper with inputs from R.B. M.P.M. helped with editing the draft. All the authors read and approve the draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bondada, R., Somasundaram, S., Marimuthu, M.P. et al. Natural epialleles of Arabidopsis SUPERMAN display superwoman phenotypes. Commun Biol 3, 772 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01525-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01525-9

This article is cited by

-

Gametophytic epigenetic regulators, MEDEA and DEMETER, synergistically suppress ectopic shoot formation in Arabidopsis

Plant Cell Reports (2024)

-

Genome-wide identification of the C2H2-Zinc finger gene family and functional validation of CsZFP7 in citrus nucellar embryogenesis

Plant Reproduction (2023)

-

A simple flow cytometry-based assay to study global methylation levels in onion, a non-model species

Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants (2021)